VIETNAM NATIONAL UNIVERSITY

UNIVERSITY OF LANGUAGES AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

FINAL ASSIGNMENT

CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS

Lecturer:

Dr. Nguyễn Huy Kỷ

Student:

Nhâm Thị Hồng Mai

Code:

20045273

Hanoi, June, 2021

Question 1: What is Contrastive Linguistics? Is it the same as Comparative

Linguistics? How are they different?

What is Contrastive Linguistics?

There have been various definitions of Contrastive Linguistics by scholars or

researchers around the world. In the following analyzation, I would like to firstly

define the Contrastive Linguistics; and secondly, examine the differences between

‘to contrast’ and ‘to compare’ in Contrastive Analysis (C.A).

James (1980) delineates CA as a linguistic enterprise aimed at producing

inverted (i.e. contrastive, not comparative) two-valued typologies and founded

on the assumption that languages can be compared.

According to Johansson and Hofland (1994:25), "language comparison is of great

interest in a theoretical as well as an applied perspective. It reveals what is general

and what is language specific and is therefore important both for the understanding

of language in general and for the study of the individual languages compared".

Besides, Fisiak (1981) defines Contrastive Linguistics as “a sub-discipline of

linguistics” concerned with the comparison of two or more languages or

subsystems of languages in order to analyze both the differences and similarities

between them.

Oluikpe (1982) states that C.A. is the one in which the similarities and differences

between two (or more) languages at particular levels are explicated in particular

context of a selected theoretical framework.

Wikipedia provides the definition of Contrastive Linguistics as a practiceoriented linguistic approach that seeks to describe the differences and

similarities between a pair of languages (hence it is occasionally called

"differential linguistics")

What are the linguistic components of CA?

The framework within which the two linguistics descriptions are organized

mean 3 things. First, CA adopts the linguistics tactics of diving up the unwieldy

concept "a language" into three smaller and more manage- able areas: the levels

of phonology, grammar and lexis. Secondly, use is made of the descriptive

categories of linguistics: unit, structure, class, and system. Thirdly, a CA utilizes

descriptions arrived at under the same 'model' of language. We shall now

consider each of these in turn.

A. Levels of Language

The four descriptive statements of our hypothetical native speaker is each made

on a different level:

a) on the level of phonology

b) on the level of lexis

c) on the level of morphology

d) on the level of syntax

1. Procedural Orientation

On account of the linguists’ perception of feasibility and a conviction that the

phonology of a language is somehow ‘basic’ and merits priority in description,

the traditional procedural direction has been dictated that the order of

descriptions follows phonology, morphology and syntax. However, in fact, the

procedural orientation of describing the phonology initially has been observed

relatively or entirely neglected of the other descriptive levels.

2. Mixing Levels

It is regulated that ‘mixing of levels’, i.e. the level of phonology is described

with other linguistics level, is not allowed. However, these days, mixing is

accepted because of the relation of some language fact.

All CA follow 2 steps: first, the stage of descriptions is introduced when one of

the two languages is described on the suitable level; second, the stage of

juxtaposition is carried out for comparison. The action of cross levels could be

performed at both stages, but it will be frequently seen at the comparison stage.

B. Categories of Grammar

According to Haliday (1961: 274), there are 4 fundamental categories: unit,

structure, class, system. The units of grammar, which are arranged on the scale

from ‘largest’ to ‘smallest’, include: sentence – clause – phrase – word –

morpheme. This order implies a scale called the rank scale. In terms of structure,

Haliday suggests that “A structure is thus an arrangement of elements ordered in

‘places’”. In English, the structure of the unit clause contains Subject,

Predicator, Complement and Adjunct. Regarding class, there are 3 elements:

noun phrase, verb phrase which plays the role of the Predicator, and adverbial

phrase which occurs as Adjunct. About system, each category owes a system:

systems of sentences, of clauses, of groups, of words and of morphemes. To be

more specific, systems at rank are mood, transitivity, theme and information.

For the mood system, we normally recognize indicative and imperative or

declarative and interrogative. In English, the system of number offers a choice

between singular and plural. Besides, English also operates system of case as

common and genitive.

C. Language Models for CA on the Grammatical Level

There are numerous models for use in CA, according to James (1980) such as

the structuralist or ‘taxonomic’; the Chomskyan ‘Standard T-G’; Krzeszowski’s

Contrastive Generative Grammar and Fillmore’s Case Grammar.

1. Structural or ‘Taxonomic’ Model

The structural model is known as Immediate Constituent analysis which claims

that any grammatical construction could be reduced to pairs of constituents. This

model enables us to measure the difference in grammatical structure and to

establish what is the maximum difference between any two language systems.

Applying Immediate Constituent analysis in a noun phrase, we see that lovely

old toy (lovely + old toy) and very old toy (very old + toy) can be analyzed in 2

ways. Therefore, firstly, the decision of the distribution is determined by what

naturally goes with what, and secondly, by the basis of omissibility: if old is

omitted in the later, *very toy is a grammatically error. As a result, it can be

concluded that adjective can go with noun, but the combination of adverb and

noun is a non-construction. This type of analysis suggests that language is

structured on two axes which are horizontal axis describing construction-types

and vertical one defining the possibility of fillers for each position.

2. Transformational-Generative Grammar

The Transformational-Generative Grammar, i.e. recognize a level of deep

structure and a level of surface structure, sets out to specify the notion of and

limits of grammaticality for the language under its purview. In this method, the

structure is related by sets of transformation. While the syntactic component of

the grammar is ‘generative’, i.e. the combination of two senses: projective and

explicit, the semantic component is ‘interpretative’.

3. Contrastive Generative Grammar

According to James (1980), CA involves 2 phases: independent description and

comparison while Krezeszowski (1974, 1976) states that ‘classical’ CAs are

‘horizontal’ in nature which are restricted to statements of 3 kinds of interlingua

relationship: those existing between L1 and L2 systems, or structures, or

transformational rules. Besides, Krzeszowski’s alternative, manifest in CGG is a

vertical CA. This type includes 2 features: it is a single bilingual grammar; it

proceeds in its origins from universal semantic inputs to language-specific

surface structure outputs in five stages (semantic, categorical, syntactic, lexical,

post-lexical).

4. Case Grammar

According to Birnbaum (1970), there are 2 types of deep structure: profound

structure and universal base hypothesis. The former is more complicated and

various than the later which is more simple. It has been proposed that the

‘profound’ deep structure in any language following the form that a sentence

consists a proposition and its modality. In CA, Case Grammar is considered as a

model met the CA’s purpose. Firstly, its finite universal array of groups enables

us to identify a common point of departure for any sentences we compare

structurally. Secondly, all the advantages of the transformational approach apply

well thanks to the surface structure.

Is it the same as Comparative Linguistics? How are they different?

Firstly, contrastive linguistics can be regarded as a branch of comparative

linguistics that is concerned with pairs of languages which are ‘socio-culturally

linked’. Two languages can be said to be socio-culturally linked when (i) they are

used by a considerable number of bi- or multilingual speakers, and/or (ii) a

substantial amount of ‘linguistic output’ (text, oral discourse) is translated from

one language into the other. According to this definition, contrastive linguistics

deals with pairs of languages such as Spanish and Basque, but not with Latin and

(the Australian language) Dyirbal, as there is no socio-cultural link between these

languages.

Secondly, the term ‘contrastive linguistics’ is also sometimes used for comparative

studies of (small) groups (rather than just pairs) of languages, and does not require

a socio-cultural link between the languages investigated. On this view, contrastive

linguistics is a special case of linguistic typology and is distinguished from other

types of typological approaches by a small sample size and a high degree of

granularity. Accordingly, any pair or group of languages (even Latin and Dyirbal)

can be subject to a contrastive analysis.

A comparative and contrastive linguistic analysis differs considerably from a

contrastive linguistic analysis. A comparative study is a diachronic comparison of

two or more linguistic systems with a view to classifying languages into families.

It is concerned with the history and evolution of languages. A comparative study is

interested in establishing the similarities or correspondences between languages.

A contrastive linguistic study is a synchronic comparison. It studies languages

belonging to the same period, without paying much attention to their histories or

language families. It is more concerned with dissimilarities than similarities.

Question 2: To the best of your knowledge and experiences, can you give

examples for illustration for the question mentioned above to show how you

can apply it/ them in your teaching institution?

A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF NOUN PHRASES IN ENGLISH

AND VIETNAMESE

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this study is to indicate the differences of noun phrases between

English and Vietnamese and their influences in teaching and studying English in

Vietnamese context. Then, several pedagogical implications for those are also

stated. Through a contrastive view in this paper, I hope that I am able to clarify

the similarities and differences of English and Vietnamese noun phrases in terms

of their internal and external structures so that teachers can avoid making

mistakes and confusion in their translation.

I.

ENGLISH NOUN PHRASES

1.

Definition

According to L. H. Nguyen (2004), a noun phrase is a group of words with a

noun or pronoun as a main part (the head). The noun may only consist of a one

word such as “Tom, table” or it may be long and complex like “the cat that I

bought yesterday”.

2.

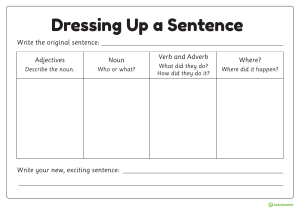

English noun phrase elements

In English grammar, a noun phrase has three components:

Pre-Modification

HEAD

Post-Modification

(optional)

(obligatory)

(optional)

The old

man

standing in front of the

shop

If the NP has more elements than the head, it may contain one or more premodifiers and/or one or more post-modifiers

2.1.

Pre-modification: consists of all the words placed before the head.

2.1.1. Determiner

A determiner is an optional element in a noun phrase that occurs at the front

most position in a noun phrase. It consists of Pre-determiner, CentralDeterminer, Post-determiner.

She meets [all her many friends]

[Pre-central-post- Noun]

2.1.2. Pre-modifier

Pre-modifiers are placed before the head, including nouns, adjective phrases

and participle phrases.

2.2.

The head

The word “noun phrase” means that a noun is the central element of a noun

phrase. That word is called “the head”. It may be an uncountable or a countable

noun or a pronoun. There are some kinds of pronouns functioning as heads:

personal pronoun, indefinite pronoun, possessive pronoun, and demonstrative

pronoun.

Eg:

He in he is my teacher.

Someone in someone in the room.

My in my is expensive.

That in that will affect his life.

2.3.

Post-modifier

Post modifiers are placed after the head includes prepositional phrases, relative

clauses, non-finite clauses and complementation.

3.

Function

Functions

Examples

Subject

The thief escaped.

Subject complement

She is a student.

Direct and indirect object

John gives {me} {a bar of candy.}

Direct - Indirect

II.

VIETNAMESE NOUN PHRASES

A noun phrase is a free combination of a noun nucleus and one or more than one

subordinate elements which are of 2 types: front element (Pre-nominal

modifiers) and end element (Post-nominal modifiers). (Doan, T.T., Nguyen, K.

H., Pham, N. Q., 2001).

In Vietnamese grammar, the noun phrase has the following structures.

Pre-modification

Totality

Articl

Quantifier

Head

Post-modification

Classifier N

Attributive

e

Demonstrative Prepositional

phrase/

modifiers

Cả

sác

bốn

cuốn

1.

Pre-nominal modifiers

1.1.

Articles (Art)

h

Possessive

Anh Việt

này

của tôi

Most researchers argue that there are no lexical articles in Vietnamese. In fact,

Vietnamese has a class of lexical articles. According to T. C. Nguyen (1975),

“một”, “những”, “các” are articles in Vietnamese. Where classifiers are used,

articles must precede the classifiers and the head noun as in:

“những con chim”

Art- CL-N

The article “một” is also an optional element in Vietnamese noun phrase and

precedes the head noun but where there is the presence of this article, it carries a

singular and indefinite interpretation as in “cô ấy bán một cuốn sách”

Sometimes “một” function as the numeral but the indefinite article “một” differs

from the homophonous numeral in a certain aspect.

1.2.

Numerals

Numerals occur in Vietnamese noun phrases with the word order [Num-CL-N].

They are express through system called cardinal number such as “một, hai, ba,

etc”. As I have already mentioned, Vietnamese numerals precede the particle

CÁI and classifiers or measure phrases (if there is one) as given below: Hai CÁI

bạn nhân viên này.

1.3.

Quantifiers

Vietnamese quantifiers are words that can occur within a noun phrase before a

head noun (with or without a classifier).

Estimated quantity: mấy, vài, dăm,…

Distribution: mọi, mỗi, từng, tất cả, toàn bộ,….

2. The head

The head of a noun phrase can be a single noun (e.g.: bàn) or a classifier + a

noun (e.g.: cái bàn).

Nguyen Tai Can claims if the noun is preceded by a classifier, both the noun and

the classifier form the head, so the head is the combination of T1 and T2.

Pre-modifier

Một

Head

Post-modifier

T1 (classifier)

T2 (noun)

cái

thảm

mới

According to K. L. Nguyen (2004), the two most widely used classifiers in

Vietnamese indicate inanimacy (“cái” as in “cái ghế”(chair)) and animacy

(“con” as in “con chó” (dog)). There are also many words that classify the shape

and size of objects such as “cuốn” (long and cylindrical) in “cuốn phim”

(camera film), “miếng” (small piece) in “miếng vải” (small piece of [torn] cloth)

and “cây” (long and slender) in “cây vàng” (long piece of gold).

Two classifiers cannot co-occur in the same noun phrase as illustrated follow:

Grammatical: cái ghế, con chim, người đàn ông

*Ungrammatical: con ghế, cái gà, cái đàn ông, cái con ghế, con cái chim

3.

Post-nominal modifiers

Noun can have any of the following post-modifiers: NPs, adjective phrases,

prepositional phrases, relative clauses, demonstrative, or possessive

phrases.

3.1.

Adjective phrases (AP)

The adjective may be preceded by an intensifier such as rất, hơi, khá as in Cái

ghế khá cũ. In case, there is a noun adjunct, the AP must follow the Noun

adjunct as in:

Quạt [trần] [cũ]

NP- NA- AP

3.2.

Possessives (PossP)

In Vietnamese grammar, Possessives are expressed by a prepositional phrase

consisting of preposition “của” (“of”) plus a possessor. The possessor can be a

personal pronoun, a kinship term, a proper name, or a full NP.

In Vietnamese, if there is co-occurrence between a PossP and an AP or PP in a

noun phrase, the PossP always follows the AP or PP. For example,

Một con cá vàng [của tôi]

Art- CL- N- AP – PossP

Những quyển sách [trong phòng ngủ] [của tôi]

Art- CL -N- PP - PossP

4.

Functions

Functions

Examples

Subject

Hà Nội là thủ đô của Việt Nam.

Predicate

Cả làng này đều nhà ngói.

Noun modifier (định ngữ)

Câu chuyện hài này rất nhạt nhẽo.

Object

Tôi đang làm bài tập.

.

III.

CONTRAST BETWEEN ENGLISH NOUN PHRASES AND

VIETNAMESE NOUN PHRASES

1.

Similarities

1.1.

Elements

English and Vietnamese noun phrases have some similar elements such as

article, demonstrative, possessive, etc. They may be in different word order but

they have the same functions which help the head noun have the clear meaning.

1.2.

Functions

English and Vietnamese noun phrases all share the same functions to each other

such as subjects, noun modifiers, objects and adverbials.

2.

Differences

2.1.

Word order

Another aspect that we need to pay attention to is word order. The order of subconstituents of English noun phrases is more rigid than that of Vietnamese noun

phrases.

Word order

English

Determiner – adjective - noun

Vietnamese

Classifier – noun - adjective

Classifier

Simultaneously, Vietnamese possessives are prepositional phrases beginning

with “của”. They follow the head noun and normally occur as the right most

position in a noun phrase as in: Những con chim trong lồng của tôi rất quý. That

is not the case of English possessives. They are pre-determiners in noun phrases

thus precede the head nouns as in the following sentence: My friend is very

generous.

Then, in Vietnamese noun phrase, noun does not allow any modifying adjective

phrase to its left. In English, on the other hand, we can put an adjective phrase

before the head noun. Thus, it’s acceptable to say “a new table” in English but

we cannot say “một chiếc mới bàn” in Vietnamese.

In addition, in Vietnamese, ordinal numerals occur post-nominally and are

introduced by the marker thứ ‘order, rank’ as in: Tôi là người con thứ nhất trong

gia đình. In English, on the contrary, ordinal numbers precede the head noun so

the sentence below is grammatical in English: The first cat is more beautiful.

It’s important to notice that in English noun phrase, it is possible to use

quantifiers to function as pre-determiners or post-determiners as in:

All these books

PreD-Dem- NP

The several rooms of the house

Art- PostD-NP

2.2 Hierarchy relationships

In terms of hierarchical relationship, I would like to discuss the following main

points.

First of all, the occurrence of English nouns and determiners is obligatory,

whereas that of Vietnamese is optional. Therefore, the following sentence is

ungrammatical: I buy table. However, in Vietnamese, the sentence “Tôi mua

bàn” is grammatical. Furthermore, where the English language is concerned,

there can be as many as three determiners prior to the head noun as shown in the

following

[The first two] answers

Article- ordinal-cardinal

Secondly, the optional element- particle CÁI can appear in Vietnamese noun

phrase as in: ba CÁI ghế kia. In English language, there is no such case.

IV.

PEDAGOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

From what I have discussed so far, I would like to suggest some teaching

implications for teaching as well as studying English as a second language.

Actually, students tend to translate their target language based on knowledge of

their mother tongue. Hence, due to differences in hierarchical relationships,

word order, and co-occurrence restrictions between English and Vietnamese

noun phrases, students are easy to make mistakes when translating from English

to Vietnamese and vice versa.

Firstly, they tend to put the wrong order of constituents in a noun phrase. For

example, the Vietnamese expression “một quyển sách quý” may be translated

into English like this “a book precious”. Therefore, as teachers we should give

enough explanation of negative transfers in word order between the two

languages or we give some funny expressions like “beautiful girl” “handsome

boy” and distinguish them with “cô gái xinh đẹp” and “cậu bé đẹp trai”,

respectively so that students may have some impressions of this grammar point.

Secondly, the occurrence of English nouns and determiners is necessary,

whereas that of Vietnamese is optional. Therefore, Vietnamese students tend to

produce nouns alone, without any determiners or sometimes, they cannot find

the equivalent determiners in Vietnamese. For instance, there is a slight

difference between the articles “các” and “những”. “Các” can only occur in

contexts that denote definite noun phrases while “những” can only occur in

contexts that denote indefinite ones. As a result, students tend to miss “the”

when translating the expression “Các quyển sách quý” into English: “precious

books” instead of “the precious books”.

transfers so that they can avoid making these mistakes.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, noun phrases in English and Vietnamese have some interesting

thought-provoking differences that are really necessary to recognize. That is not

only for implication in teaching but also in translation. In general, there are

some similarities in the internal and external English and Vietnamese noun

phrase. However, there are still some important differences between them. I

hope that this paper, to a certain extent, will provide language teachers some

ideas for their teaching of noun phrases.

REFERENCES

1. Ban, D. Q., & Thung, H. V. (1991). Ngữ pháp tiếng Việt, tập 2. NXB Giáo

dục, Hà nội.

2. Clark, M. (1978). Coverbs and case in Vietnamese. Pacific Linguistics, Series

B, No. 48. Canberra.

3. Eastwood, J. (1994). Oxford guide to English grammar. Oxford University

Press.

4. Jacob, R. A. (1995). English Syntax: A Grammar for English Language

Professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

5. James, C. (1980). Contrastive Analysis.

6. Kosur, H.M (2009). English Nouns and Noun Phrases.

7. Nguyễn, T. C. (2007). Ngữ pháp tiếng Việt. Đại Học Quốc Gia Hà Nội.