Childhood Disability Screen Reliability Across Cultures

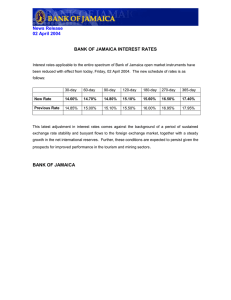

advertisement

J Clin Epidemiol Vol. 48, No. 5, pp. 657-666, 1995 Copyright 0 1995 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved 0895-4356/95 $9.50 + 0.00 0895-4356(94)00163-4 EVALUATING A TEN QUESTIONS SCREEN FOR CHILDHOOD DISABILITY: RELIABILITY AND INTERNAL STRUCTURE IN DIFFERENT CULTURES M. S. DURKIN,‘,*,‘* W. WANG,4.5P. E. SHROUT,6 S. S. ZAMAN,‘Z. P. DESAP and L. L. DAVIDSON1~*~iO M. HASAN,* IGH Sergievsky Center, Faculty of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY, U.S.A., 2Division of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, U.S.A., ‘New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, U.S.A., ‘Division of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, U.S.A., SNathan Kline Institute, Rockland, New York, NY, U.S.A., Department ofPsychology, New York University, New York, NY, U.S.A., Departments of Psychology, New York University, New York, NY, U.S.A., ‘Departments of Psychology and Special Education, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh, *Department of Neurophyschiatry, Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi, Pakistan, 9Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston, Jamaica and lODepartment of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY, U.S.A. (Received in revised form 30 August 1994) Abstract-This paperusesfive strategiesto evaluatethe reliability and other measurement qualitiesof the Ten Questionsscreenfor childhooddisability. The screenwasadministered for 22,125children,aged2-9 years,in Bangladesh,Jamaicaand Pakistan.The test-retest approach involving small sub-samples was useful for assessing reliability of overall screeningresults,but not of individual itemswith low prevalence.Alternative strategies focus on the internal consistency and structure of the screen as well as item analyses. They provide evidence of similar and comparablequalities of measurementin the three culturally divergent populations, indicating that the screen is likely to produce comparabledata acrosscultures.One of the questions,however,correlateswith the other questionsdifferently in Jamaica,whereit appearsto “over-identify” childrenasseriously disabled.The methodsand findings reported here have general applications for the design and evaluation of questionnaires for epidemiologic research, particularly when the goal is to gather comparabledata in geographicallyand culturally diversesettings. Child developmentdisorders Cross-culturalcomparison Disability Epidemiologic methods Questionnaires Reliability Reproducibility of results INTRODUCTION When comparing epidemiologic characteristics of a health condition across populations that differ in language and other aspects of culture, the comparability of the assessmentprocedures is a specialconcern. Cross-cultural equivalence is *All correspondence and reprint requests should be addressed to: Dr Maureen Durkin, Columbia University, Sergievsky Center, 630 W. 168 Street, New York, NY 10032, U.S.A. 651 especially problematic when assessments depend on verbal reports of individuals sampledfrom the population. In such instances, researchersmust not only develop a survey questionnaire that is standard and unambiguous, but must also show that population characteristics such as preferred language, level of education and cultural values do not affect the quality of the assessment. Quality of measurement is typically characterized in terms of reliability (the degree to which a measurementproduces systematic variation) and 658 M. S. Durkin validity (the degree to which the measurement is useful for its intended purpose) [ 1,2]. Validity of a screening instrument is the ultimate criterion for choosing a screen. It is tested by comparing the screen to an established external criterion, such as a clinical assessment. Reliability is important because it is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for validity. If the screen does not produce systematic variation, it cannot be valid. Moreover, reliability is a measurement characteristic that can often be improved, both by clarifying questions and measurement procedures, and by averaging replicate measurements. Such improvements will often improve validity. Furthermore, reliability can be studied prior to fielding of costly validity studies. Estimates of reliability are obtained by replicating measurements, and often the extent to which replication will be obtained can be inferred from examination of responses to similar items within a screen (see below). In this paper we focus on reliability of a screen for an additional reason. In cross-cultural research the examination of reliability and internal structure of measures can provide some assurance that the measures do not vary according to culture or translation. The logic of the reliability analyses can be extended to individual items, as well as composite screening scores, and items that appear to lack cross-cultural robustness can be removed or revised to provide more comparable measurement. An advantage of reliability over validity analysis for assessing cross-cultural comparability is its reliance on internal properties of the screen rather than an external criterion that may itself vary across cultures (due to differences in training, clinical style and other factors). The screening instrument evaluated here is the Ten Questions, a questionnaire designed to detect serious childhood disabilities in 2- to 9-year-old children. It is intended as a tool for focussing scarce professional resources in heterogeneous cultures in developing nations. In previous papers we have shown this screen to be sensitive cross-culturally for detecting serious cognitive, motor and seizure disabilities, but that it is not sensitive for identifying serious vision and hearing disabilities that have not been previously detected [3,4]. A fundamental question addressed in the present paper is: To what extent does the screen produce similarly systematic data in the three populations studied, communities in Bangladesh, Jamaica and Pakistan? To address this question, the paper et al. uses five alternative approaches to evaluate reliability. We begin with a brief review of the classic mathematical definition of reliability [5]. Theory of reliability and its estimation Suppose that the variable X represents the result of an assessment process. The variance of X, a$, is a population parameter that is likely to differ across populations. According to classic reliability theory, it is useful to decompose ai into at least two components, 0: = ai + a$, where ai is variance due to non-systematic stochastic processes (random error) and a$ is variance due to systematic differences between objects or persons being measured. The reliability coefficient is a ratio of the population parameters, a: and a$: a $, = 8:/a; = a’,/[a’, + a:]. The reliability coefficient varies from zero (X is due entirely to unsystematic stochastic processes) to unity (Xis due entirely to systematic individual differences). For a complete development of p$, and its implications, see Lord and Novick [5]. To estimate p$r we need to operationalize what is meant by systematic variation of X, and then to design a study to collect data on systematic variation. The most common design calls for making the X measurement at two points in time (the test-retest design). Changes in the X values for the same respondent are used to estimate ai, and this can be used with the observed Xvariance to estimate p&. Although theoretically and intuitively appealing, this design includes systematic biological, psychological and social changes over time in its estimate of ai, and consequently may underestimate the instantaneous reliability of the first assessment. Some of these changes may be due to the interview process itself: informants may think about the questions and form new opinions about how they should have answered. The test-retest design is also subject to memory artifacts: respondents may remember at time 2 random responses made at time 1, and thereby inflate the reliability estimate. Methodologists who address these issues recommend that the second assessments be carried out after a long enough period to reduce memory artifacts, but promptly enough to reduce the probability of systematic changes. Recommendations of how long the period should be are more products of opinion than science. Inferences about the degree of stochastic variation in X can be made on the basis of data other than those collected over time. If different Ten Questions Reliability 659 questions can be asked in a questionnaire about strategies involve analyses of the individual a single underlying condition or process, then the items. One looks at test-retest reliability, another degree to which the answers to those questions at factor scores from a factor analysis, and the are systematic can be used to establish that the final one is an analysis of the item response assessments are reliable in the general sense process (described below). described above. These inferences are made on the basis of the internal consistency of the MATERIALS AND METHODS questionnaire responses. Three indicators of internal consistency used in this paper are: (1) The Ten Questions is a brief questionnaire Cronbach’s alpha coefficient [6]; (2) factor administered to parents as a personal interview. loadings from a factor analysis [7]; and (3) the Five of the questions are designed to detect item response curve [8], an indicator of how well cognitive disability, two questions relate to a given item distinguishes between respondents movement disability, and there is one question with high and low scores on the trait the each on seizures, vision and hearing, respectively instrument is intended to measure. Unlike (see Appendix) [3,4, 12, 131. The target age test-retest designs that obtain replicate measure- group is 2-9 years. The Ten Questions screen is ments over time, internal consistency designs intended as a rapid and low-cost method of attempt to obtain replicate measurements within case-finding in communities such as those in less a single interview session. In addition to developed countries where many or most providing information about the reliability of the seriously disabled children have never received questionnaire items, the internal consistency professional services. design provides the basis for designing composite Three features of the questionnaire design are measures that are more reliable than the original intended to enhance its appropriateness and items. The degree to which reliability is expected measurement qualities under diverse cultural and to improve in the composites is described socioeconomic conditions: the questions are mathematically by Spearman [9] and Brown [lo] simple with a yes-no response format; they focus [see also 111. on universal abilities that children in all cultures normally acquire, rather than on culturally Like test-retest measurements of reliability, estimates based on internal consistency have specific behaviors; and they ask the parent, in limitations. Random biological and psychologijudging whether or not the child has a disability, cal processes that are irrelevant to the interests of to compare the child to others of the same age the investigator may affect all of the responses and cultural setting. given in a single interview. For example, stress or A two-phase design, screening followed by illness at the time of the assessment may clinical evaluations, was implemented in commuintroduce transient variation in X that is not nity settings in Bangladesh, Jamaica and recognized as error variation by the internal Pakistan [3,4, 12, 14-191. The screening took consistency estimators of reliability. Reliability place during house-to-house surveys and covered estimates may also be inflated if the related items all 2- to 9-year-old children in selected in the questionnaire are so similar that they are communities. In Bangladesh and Pakistan affected by the same sources of confusion. These cluster sampling was used to obtain probability limitations are offset, but not eliminated, by samples of Bangladesh and Karachi, Pakistan, considerations of the cost and feasibility of respectively. In Jamaica, all households in a internal consistency. contiguous area of Clarendon Parish were The fact that no single strategy for evaluating surveyed. The Ten Questions screen and a the degree to which a measure produces household questionnaire, translated into the systematic data is wholly satisfactory has national language of each country, were prompted us in the present analysis of the Ten administered by community workers trained as Questions to employ five complementary strat- interviewers for this study. In all, 58 interviewers egies for making inferences about the quality of screened more than 22,000 children in the three the data. The first two look at the screen as a countries (Table 1). The participation rate was single, global measure; one evaluates reliability greater than 98% in each country. The main in terms of test-retest agreement between overall reason for non-participation was that no adult screening results obtained on two occasions; the was present on at least three visits. other in terms of internal consistency of the ten To assess test-retest reliability, repeat screendisability questions (items). The remaining three ing and household questionnaires were adminis- 660 M. S. Durkin et al. tered 2 weeks after the original survey for consecutive samples of 101 children in Bangladesh and 52 children in Pakistan. Test-retest data were not available from Jamaica. Statistical analysis The responses to the Ten Questions were considered negative (coded 0) if no problem was reported and positive (coded 1) if a problem was reported. To assess test-retest consistency of the sum of positive responses to the screening questions we computed Pearson correlation coefficients [20]. To evaluate testretest reliability of dichotomous outcomes (individual item responses and overall positive vs negative screening results), we computed kappa coefficients [21]. To measure internal consistency reliability we computed Cronbach’s alpha [6]. Factor analysis [7], used to evaluate the reliability of individual items, was based on tetrachoric correlations [5,22] of the items. The factor loadings on a single factor are interpreted as the correlation between each item and the common factor measured by the ten questions as a whole. If the item evokes random or unreliable responses, its factor loading is expected to be zero. The final method used to evaluate the reliability and cross-cultural comparability of individual items involved evaluation of item characteristic curves [8]. Each of these curves provides insight into the ability of a specific item to distinguish children with lower from those with higher scores on a disability scale (a scale comprised of items from the Ten Questions screen found in the factor analysis to measure a common dimension, excluding the item under consideration). The curve for a given item describes the probability that the item will be endorsed for children with increasing levels of disability (i.e. scores on the disability scale). Curves that are steep in the center of the graph indicate the item effectively distinguishes between children with lower and higher levels of disability. Because only reliable items could show such relationships, the item curve analysis provides an indirect method of evaluating reliability. In conjunction with the visual examination of the item characteristic curves, we used a Mantel-Haenszel procedure [23] to test whether the odds of endorsing an item is the same in a given population compared to a reference population adjusting for overall severity (as measured by the remaining items). A summary odds ratio greater than one, for example, indicates that an item is more likely to be endorsed in a given population than in a reference population, holding disability level constant. RESULTS The three populations of children are similar in terms of age and gender distribution, but they differ in socioeconomic and cultural characteristics (Table 1). In education and most economic indicators, Jamaica is the most developed and Bangladesh is the least developed of the three populations (Table 1). Karachi is the most urbanized of the three. The populations have different rates of response for some items and similar rates for other of the Ten Questions (Fig. 1). The most striking difference is for Question 10 (which reads: “Compared to other children, is this child in any way backward, dull or slow?‘); in Jamaica it elicited a much larger proportion of positive responses than any of the other questions and than any question in the other two populations. In Pakistan, the percentages of positive responses to Questions 1, 5, 6 and 9 were considerably higher than in the other two populations. Otherwise, the patterns of responses in Fig. 1 show some similarity in the three populations. In all three populations, the questions on milestones (Question 1) and unclear speech (Question 9) elicited frequent positive responses, while the questions on comprehension (Question 4) learning (Question 7) and no speech (Question 8) elicited the fewest positive responses. The overall percentages screened positive (on any question) were much higher in Jamaica and Pakistan than in Bangladesh (15.6 and 14.7 vs 8.2%, respectively). Analysis of the reliability of the screenas a global measure The test-retest reliability results for the screen as a whole (for both the sum of positive items, and for the dichotomous outcome of positive/ negative screen) indicate acceptable or good reliability in both populations where test-retest data were available (Bangladesh and Pakistan, Table 2). In Bangladesh and Pakistan the test-retest reliabilities for total scores (correlation coefficients) were, respectively, 0.58 and 0.83 (Table 2). Consistent with these results, the internal consistency reliabilities indicated by Ten Questions Table Reliability 1. Number and background characteristics of the children screened and clinically evaluated in the three populations Bangladesh Number of children screened Number of inierviewers Child characteriastics Boys (%) 2-5 years (%) 69 years Attends school (among ages 5-9) (%) Born at home (%) Received any immunizations (%) Household characteristics Language Religion from semi-rural residence q q Pakistan 5,461 8 6,365 19 52.6 48.0 52.0 49.2 52.4 47.6 53.8 53.0 47.0 57.5 89.2 96.5 30.6 68.8 48.6 32.6 91.1 77.2 Bangla Muslim (91.4%) English Christian (89.0%) Urdu Muslim (94.4%) 26.6 50.4 45.4 26.8 49.9 7.3 * 55.5 80.3 74.0 4.4 9.7 94.5 77.3 68.3 39.3 99.4 39.4 area. alpha coefficients for these two countries were 0.60 in Bangladesh and 0.66 in Pakistan. We also have the alpha coefficient of reliability for Jamaica, which is 0.60, similar to the other two countries. Also shown in Table 2 are the test-retest reliabilities for the dichotomous screening outcome (positive vs negative), which are lower than those for the continuous outcome. This is as expected because of the loss of information resulting from dichotomizing a continuous variable. - Jamaica 10,299 31 Agricultural occupation Rural residence (%) Electricity (%) Radio (%) Water tap (%) Mother attended primary school (%) *All 661 Analysis items of the reliability of individual screening The test-retest results for individual items are generally not informative due to the limited number of persons who were positive on each item (Table 2). For four of the items in Bangaldesh and five of the items in Pakistan, kappa coefficients could not be calculated due to lack of variation (no positive responses within the retest sample). For the remaining questions, the estimated kappa coefficients are generally Bangladesh Jamaica Pakistan Ql Q2 Q3 44 QS 46 Q7 Q8 Q9 QIO Any Q* Ten questions Fig. 1. Percentage with positive responses to the Ten Questions in the populations Jamaica and Pakistan. surveyed in Bangladesh, M. S. Durkin et al. 662 Table 2. Test-retest reliability of the Ten Questions: kappa coefficients for dichotomous, Pearson correlation coefficients for continuous variables (95% confidence intervals*) Bangladesh Pakistan Number of children retested 101 52 Global screening result 0.58 (0.43-0.69) 0.48 (0.24, 0.72) Sum of problems reported on the ten questions Screened positive (positive on any of the ten questions) Individual 0.83 (0.734.90) 0.67 (0.37, 0.97) items 1. Milestones 0.49 0.79 (-0.12, 1.0) (0.38, 1.0) 2. Vision 1.00 t (0.80, 1.O) 3. Hearing 0.52 t (0.15, 0.89) 4. Comprehension t t 5. Movement 0.49 0.79 (-0.12, 1.0) 0.39, 1.0) 6. Seizures 0.32 0.66 (-0.18, 0.57) 0.03, 1.0) 7. Learning t 1.00 (1.0, 1.0) 8. No speech t t 9. Unclear speech 0.58 1.oo (0.21, 0.95) (0.73, 1.0) 10. Slowness t -0.02 (-0.05. 0.01) *For dichotomous variables, confidence intervals were computed with non-null standard errors, except when the point estimate of the kappa coefficient was equal to 1. tThe kappa coefficient could not be calculated because no children in the sample had a positive response to this question. unstable (indicated by wide confidence intervals), and not useful for assessing the comparability of the reliability of the screen in different cultures. 0 .E -2 0 1.0 r 0.6 - The two alternative methods for evaluating the reliability and cross-cultural comparability of individual items, factor analysis and item characteristic curves, are not as constrained by sample size as the test-retest approach because they make use of data on all children screened. The factor loadings of the ten questions are notably consistent across the three populations (Fig. 2). In all three populations, the questions on motor (Questions 1 and 5) and cognitive (Questions 4, 7, 8,9 and 10) disability have high loadings, indicating that they are correlated with a common factor; hence reliable. Also in all three countries, the loadings for the questions on vision (Question 2) hearing (Question 3) and seizures (Question 6) are relatively low, indicating either unreliability or that those items each measure something distinct from cognitive and motor disability. The pattern of eigenvalues [7] from the factor analysis unequivocally suggest a one factor model for the ten questions in each of the three countries (data not shown). Item characteristic curves were constructed for all ten items but only the curves for three exemplary items are shown [Fig. 3(a-c)]. To construct these curves, we plotted the proportion responding positively to each item for groups of respondents defined using the sum of only the motor and cognitive items (excluding the item under consideration), because it was only these seven items that form a scale with high factor loadings on the common factor. In all three populations, the questions on milestones b I& Q1 44 QS 46 47 * Bangladesh + Pakistan 0 Jamaica Q8 Q9 QlO Eight items Fig. 2. Factor loadings for the each of the ten questions in the three populations, estimated by unweighted least squares, one factor model. Ten Questions Motor 0 I 2 Motor 100 ..z cognitive disability 3 score* 4 5 disability score* disability score* 6 Cc) 0 Bangladesh 80 s5 cognitive + Jamaica 60 I * Pakistan Motor cognitive Fig. 3. Item characteristic curves for three of the ten questions, three populations. (a) Unclear speech (Question 9); (b) Slow (Question 10); (c) Vision (Question 2). (Question l), movement disability (Question 5), learning (Question 7), no speech (Question 8) and unclear speech (Question 9) have curves that are steep in the center of the graph and, therefore, appear useful for distinguishing children with disability (as measured by the six motor and cognitive items other than the one being considered). The curves for Question Reliability 663 9 exemplify this pattern and are shown in Fig. 3(a). Question 10 (on slowness) shows similar steep curves in Bangladesh and Pakistan [Fig. 3(b)]. In Jamaica the curve for this item rises steadily but the probability of a positive response to this question is high even for those with few positive responses to the other questions [Fig. 3(b)]. In all three populations, the curves for Questions 2 (vision), 3 (hearing) and 6 (seizures) show only a weak if any positive association with the sums of the seven motor and cognitive questions. For example, the curves for Question 2 [Fig. 3(c)] show that among children with positive responses to most of the seven cognitive and motor items, no more than 25% had reported problems with vision. These observations are consistent with the factor loadings in suggesting that either these three questions are unreliable (contain stochastic noise or random error) or that they measure something distinct from cognitive and motor disability. Although we have stressed similarities in their shapes, the item characteristic curves are not identical across the populations. The MantelHaenszel test results (Table 3) reveal that all ten items show significantly different relationships to severity of disability (measured by the sum of positive responses to other items) in at least two of the cross-cultural comparisons. Most of the items are significantly different in all three pairwise comparisons (i.e. confidence intervals exclude 1; Table 3). This Mantel-Haenszel test is used by psychometricians to detect item “bias” in the following sense: holding constant the estimated degree of overall disability, the probability of specific reported problems appears to differ across samples. Though significant due to large sample sizes, the differences are relatively modest for most items except Question 10, (slowness). Children who have few other problems are much more likely to be reported to be slow by parents in Jamaica than by parents in the other two cultures (the summary odds ratio for Question 10 is 22.8 when Jamaica is compared to Bangladesh and 10.6 when Jamaica is compared to Pakistan). Thus, if we were to rely on Question 10 to determine whether one population of children has a greater proportion of cognitively disabled children than another, we would most certainly obtain a biased impression. On the other hand, we note that the question is not without some strengths. Jamaican parents, like those in the other two cultures, are much more likely to attribute slowness to the children M. S. Durkin et al. 664 with apparent multiple or severe disabilities than other problems reported those without [Fig. 3(b)]. DI!XUS!3ION We have compared the reliability of the Ten Questions screen in three different cultures as a means of assessing the extent to which it achieves its goal of cross-cultural comparability. A secondary purpose of this paper has been to demonstrate how multiple methods of assessing reliability can provide complementary perspectives on the extent to which a questionnaire produces systematic data. Four of the five methods we used provided useful information on the reliability and cross-cultural comparability of the Ten Questions. These included the methods Of: (1) Test-retest reliability of the global screening result, which showed good consistency over time in the screening results for samples of children for whom repeated administrations of the screen were available. Similar levels of reliability (coefficients in the range of 0.6-0.8) have been reported for other instruments designed to detect disability, such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales [24] and the Mental Function Index [25]. (2) The computation of alpha coefficients, which indicated good and comparable levels of inter-item consistency in all three populations. (3) Factor analysis, which produced factor loadings indicating high levels of reliability for seven of the ten items in all three populations. (4) The construction of item characteristic curves, which demonstrated some consistency across the three cultures in the relationship of specific items to the common factor measured by the screen. A fifth method of assessing reliability, test-retest reliability of individual items, was not informative about the reliability or cross-cultural comparability of individual questions because stable estimates of kappa could not be made for rare problems with retest sample sizes even as large as 101 in Bangladesh and 52 in Pakistan. Because epidemiologists commonly study conditions of low prevalence, and because replication studies involving larger samples are rarely practical, these results illustrate a common limitation of test-retest studies in epidemiology. This limitation was avoided by the internal consistency approaches, which were able to make use of data on all 22,125 children screened. Within the test-retest strategy, an alternative approach is to carry out studies in a “fortified” (e.g. patient) sample, with a high prevalence of disorder. Thompson and Walter [26], however, point out that the reliability of a measure in a Table 3. Mantel-Haenszel odds ratios* (95% confidence intervals) indicating variations between countries in the odds of positive responses to each of the seven cognitive-motor questions on the ten questions screen, among children with matching scores on the sum of the remaining six cognitive-motor questions Index population: Pakistan Jamaica Jamaica Reference population Pakistan Bangladesh Bangladesh Questions 1. Milestones 1.43 0.41 0.27 (1.09, 1.89) (0.30, 0.57) (0.20, 0.36) 4. Comprehension 0.30 0.71 2.48 (0.17, 0.51) (0.43, 1.16) (1.41, 4.39) 5. Movement 0.72 0.44 0.58 (0.53, 0.98) (0.31, 0.63) (0.42, 0.81) 7. Learning 0.50 1.00 2.03 (0.28, 0.90) (0.60, 1.69) (1.22, 3.26) 8. No speech 0.34 0.61 1.83 (0.20, 0.56) (0.38, 0.99) (1.11, 3.03) 1.53 0.43 0.29 9. Unclear speech (1.18, 1.98) (0.32, 0.59) (0.22, 0.37) 10. Slowness 2.24 22.8 10.61 (1.54, 3.25) (16.4, 31.6) (8.34, 13.50) *An odds ratio greater than 1 indicates that the probability of a positive response to the question is greater in the index population than in the reference population, among children with matching scores on the sum of the remaining six questions; an odds ratio less than 1 indicates that the probability of a positive response is lower in the index population than in the reference population. Ten Questions high prevalence sample cannot necessarily be generalized to a community population where prevalence is low, since some measures of reliability are affected by prevalence. The reliability of a measure is best evaluated in a sample that is representative of the population for which the measure is intended. The similarity across cultures in the patterns of factor loadings and item characteristic curves indicates considerable cross-cultural comparability in the ways that the ten questions correlate with each other. The high loadings and steep curves for the seven cognitive and motor items in all three populations indicate that these items are reliable in each of the populations studied. In all three populations the questions on vision, hearing and seizures have the lowest factor loadings as well as flat item curves, suggesting that these questions may consistently identify two different groups of children with vision, hearing or seizure disabilities-one group with cognitive and/or motor disability and the other group without these complications.* Thus, the lack of evidence of reliability for the questions on vision, hearing and seizures could reflect the heterogeneity of childhood disability and its causes. Both the factor analysis and item characteristic curve methods of evaluating the reliability of individual items assume those items measure a common factor or trait that is measured by the remaining items in the scale. If this assumption does not hold for the vision, hearing and seizure questions, these methods are not informative about the reliability of those items. Our inability to demonstrate reliability of the questions on vision, hearing and seizures, therefore, does not necessarily imply that these questions are not useful. A previous analysis of the validity of the Ten Questions suggested that dropping any one item would result in a loss of sensitivity [4]. The item characteristic curves for Question 10 (on slowness) reveal a striking difference across countries, suggesting that Question 10 is a biased item and should be used with caution in comparing children of different cultural backgrounds. Although the cross-cultural differences in the item characteristic curves are most striking *As with vision, hearing and seizure problems, motor disabilities such as cerebral palsy are by no means always complicated by cognitive disorder. Yet the factor loadings for the question on movement disability are high in all three countries. This may reflect the fact that serious mental retardation is typically associated with delayed motor milestones, even if the child has no specific movement disorder. Reliability 665 for Question 10, the Mantel-Haenszel statistics revealed statistically significant differences across the populations for every individual item. Though it is true that the large sample sizes render even small differences statistically significant, these findings, nevertheless, serve to remind us that neither the individual items nor their total sum should be used uncritically to compare levels ofdisability across cultures. This limitation of the screen underscores our initial intent and previous recommendation [4, 12, 13, 17,271 that the questions be used as a first phase screen rather than an ultimate measure of disability. As long as the children who appear to have problems according to the screen are assessed in a second phase by professionals or others trained to take cultural norms and practices into account, then the potential bias, for example of over-identification of disability in Jamaica based on Question 10, is not problematic. The fact that the majority of the questions showed the expected relation to the overall level ofdisability [Fig. 3(a)] was reassuring concerning their utility as screening questions. In conclusion, these results provide considerable evidence that the Ten Questions as a whole is a reliable questionnaire and that indicators of its reliability are comparable across populations that differ in culture and level of socioeconomic development. We would not be able to support this conclusion had the reliability analysis been limited to a test-retest study of a few hundred children. The use of multiple methods of assessing the reliability of the Ten Questions has shown notable consistency as well as an important item-specific difference across cultures. The approach to assessing reliability demonstrated here has broad applications in epidemiology, especially when the goal is to gain a comprehensive understanding of the reliability of one’s data or to assess the comparability of data collected from diverse groups or settings. Acknowledgements-This work was supported by the BOSTID Program of the National Academy of Sciences (U.S.A.), the Epilepsy Foundation of America, the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (R29 NS27971-01, R29 NS27971-02, R29 NS27971-03, R29 NS27971-04) the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the Gertrude Sergievsky Center of Columbia University. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Drs Zena Stein, Lillian Belmont, Zakin Hasan, Mervyn Susser, Marigold Thorburn and others to the design and conduct of this research project. REFERENCES 1. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiologic Research: Principles and Quantitative Methods. Belmont, CA: Lifetime Learning Publications; 1982. 666 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. M. S. Durkin Feinstein AR. Clinical Epidemiology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co.; 1985. Zaman S, Khan N, Islam S et al. Validity of the Ten Questions for screening serious childhood disability: results from urban Bangladesh. Intern J Epidemioll990; 19(3): 613-620. Durkin MS, Davidson LL, Hasan ZM er al. Validity of the Ten Questions screen for childhood disability: results from population-based studies in Bangladesh, Jamaica and Pakistan. Epidemiology 1994; 5(3): 283-289. Lord FM, Novick MR. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrica 1951; 16: 297-334. Harman HH. Modern Factor Analysis, 2nd Edition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1967. Suen HK. Principles of Test Theories. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1990. Spearman C. Correlation calculated from faulty data. Psychometrica 1910; 3: 271-295. Brown W. Some experimental results in the correlation of mental abilities. Psychometrica 1910; 3: 296322. Shrout PE, Yager T. Reliability and validity of screening scales: Effects of reducing scale length. J Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42: 69-78. Durkin MS, Zaman S, Thorburn M et al. Screening for childhood disability in less developed countries: rationale and study design. Intern J Ment Health 1991; 20: 47-60. Belmont L. Screening for severe mental retardation in developing countries: the International Pilot Study of Severe Childhood Disability. In: Berg JM, Ed. Science and Technology in Mental Retardation. London: Methuen; 1986: 389395. Thorburn MJ, Desai P, Durkin MS. A comparison of the key informant and the community survey methods in the identification of childhood disability in Jamaica. Ann Epidemiol 199 1; 1: 255-26 1. Thorburn MJ, Desai P, Davidson LL. Categories, classes, and criteria in childhood disability-experience et al. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. from a survey in Jamaica. Disability Rehab 1992; 14(3): 122-132. Thorbum MJ, Desai P, Paul TJ et al. Identification of childhood disability in Jamaica: the ten question screen. Intern Rehab Res 1992: 15: 115-127. Durkin MS, Davidson’LL, Hasan ZM et al. Screening for childhood disability in community settings. In: Thorbum M, Marfo K, Eds. Practical Approaches to Childhood Disability in Developing Countries: Insights From Experience and Research Jamaica: 3D Projects; 1990: 179-197. Durkin MS, Davidson LL, Hasan ZM et al. Estimates of the prevalence of childhood seizure disorders in communities where professional resources are scarce: results from Bangladesh, Jamaica and Pakistan, Paed Perinatal Epidemiol 1992; 6: 166180. Stein ZA, Durkin MS, Davidson LL et al. Guidelines for identifying children with mental retardation in community settings. In Assessment of People with Mental Retardation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions Second Edition. New York: Wiley; 1981. Fleiss JL. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: Wiley; 1986. Mislevy RJ. Recent developments in the factor analysis of categorical variables. J Educ Stat 1986; I 1: 3-3 1. Holland PW, Thayer DT. Differential item functioning and the Mantel-Haenszel procedure. In: Wainer H, Brain H, Eds. Test Validity. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc; 1988. Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Survey Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1984. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Chance JM et al. Use of the Mental Function Index in Older Adults: reliability, validity, and measurement of change over time. Am J Epidemiol 1984; 120(6): 922-935. Thompson WD, Walter SD. A reappraisal of the kappa coefficient. J Clin Epidemiol 1988; 41(10): 949-958. Susser MW. Mental retardation and handicap in the developing world: an overview of broad issues. Intern J Ment Health 1981; 10: 117-119. APPENDIX The Ten Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Compared with other children, did the child have any serious delay in sitting, standing or walking? Compared with other children does the child have difficulty seeing, either in the daytime or at night? Does the child appear to have difficulty hearing? When you tell the child to do something, does he/she seem to understand what you are saying? Does the child have difficulty in walking or moving his/her arms or does he/she have weakness and/or stiffness in the arms or legs? Does the child sometimes have fits, become rigid, or lose consciousness? Does the child learn to do things like other children his/her age? Does the child speak at all (can he/she make himself/herself understood in words; can he/she say any recognizable words)? For 3- ro 9-year-olds ask: Is the child’s speech in any way different from normal (not clear enough to be understood by people other than his/her immediate family)? For 2-year-olds ask: Can he/she name at least one object (for example, an animal, a toy, a cup, a spoon)? Compared with other children of his/her age, does the child appear in any way mentally backward, dull or slow?