The Single Paragraph Essay (The chunk paragraph)

For your summer reading you will write a set of many single paragraph essays, each to respond to

particular chapters from Thomas C. Foster’s text, How To Read Literature Like a Professor. Your

writing should be formal and academic in nature. A single paragraph essay is the essence of a body

paragraph with a formal thesis statement at the beginning and a concluding statement at the end. When

writing a single paragraph essay, leave out the general information used to set up your thesis in the

introduction and leave out the re-thesis and implications normally used in a concluding paragraph. A

single-paragraph essay is extremely concise, a boiled down version of a full academic essay; however,

this does not mean that a writer can forego the use of concrete details and commentary. Please see the

explanation and notes provided in this document for help.

A single paragraph essay follows a “formula of sorts.” The “variables” of this formula are as

follows: T, BP, CD, CM, CM, BP, CD, CM, CM, CS.

Here is an explanation to help:

T: Thesis statement-- Start your essay with a thesis statement that contains your position and a

TAG. State a position on a topic that can be proven in the paragraph. Make sure the topic is narrow

enough to be supported by two facts (concrete details with commentary).

Body Point: BP—In a full essay, this would be the topic sentence in each body paragraph. In a

single-paragraph essay, it is an important point you make to directly prove the thesis. Either way

(full essay or single-paragraph essay), this sentence directly supports your thesis, and directs to reader’s

attention to the specific evidence you use in the concrete detail.

CD: Concrete Detail (#1)-- Use a specific example from the work used to provide evidence for your

topic sentence or to support your thesis. This comes straight from the text you are referencing. A

concrete detail can be a combination of paraphrase and direct quotation from the work. You must provide

a parenthetical citation for the concrete detail. After your sentence, before the period, in parentheses,

write the original authors name and the page/pages where you acquired the text; this gives credit where

credit is due. After your acknowledgments, you may now put a period. {e.g.: (Shakespeare, 147)}.

CM: Commentary – This is your explanation and interpretation of the concrete detail. In this

sentence you explain, in your own words, what the text (CD) means or how the concrete detail

proves/supports the thesis. This statement may include interpretation, insight, analysis, argument, and/or

reflection. In your paragraph you should have twice as much commentary as concrete detail.

Commentary 1: Comments on the importance of the concrete detail.

Commentary 2: Can comment on the statement in commentary 1 by offering a varying/opposing

idea or provide a different commentary about the importance of the concrete

detail.

BP: Body Point (see above)

CD: Concrete Detail (see above)

CM: Commentary (see above)

CS: Concluding Sentence-- This sentence wraps up the paragraph. It directly relates to the thesis

statement but does not repeat it. This is the opportunity to make your point and “drive it home.” Do not

leave the reader asking, “So what?” DO NOT introduce any new facts in this sentence. This sentence is

used to tie up the loose ends and make sure that the paragraph feels finished.

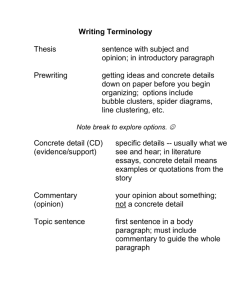

THESIS

STATEMENT with

TAG

wi

BODY POINT

CONCRETE DETAIL

COMMEN

-TARY

COMMEN

-TARY

BODY POINT (with transition word/phrase)

CONCRETE DETAIL

COMMEN

-TARY

COMMEN

-TARY

CONCLUDING

SENTENCE

Please note that you need a minimum of two (2) concrete details, and for each concrete detail you should

have two commentaries. Therefore, your paragraph will be 10-14 sentences in length depending upon

whether you have two (2) or three (3) concrete details.

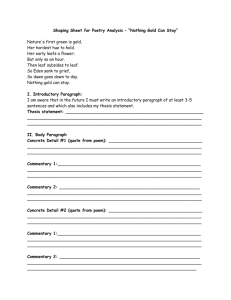

Here is another way to see it:

A planning sheet follows. After the planning sheet there is an example single paragraph essay, and a

planning sheet/chart to show how each sentence fits the requirements of the paragraph.

*** The information in this document was borrowed from the following sources:

www.janeschaffer.com.

http://everything2.com/title/The+Jane+Schaffer+Writing+Program

http://newcountryschool.com/media/EDocs/literaryguide.pdf

www.pvhigh.com (The Palos Verde High School Writing Manual)

Single Paragraph Essay Example

from Little Red-Riding-Hood

1. Chapter 6: Every Trip is a Quest (Except When It’s Not)

Charles Perrault’s beloved fairytale, “Little Red-Riding-Hood,” is more than it seems; Perrault goes

beyond a simple telling of a children’s story to share the tale of a little girl who sets out on an epic quest

to her grandmother’s house. Perrault’s story of a small girl cloaked in red easily fits the structure of quest

literature. According to Thomas C. Foster, the author of How to Read Literature Like a Professor, there

are five items needed for a text to fit the quest structure: a quester, a place to go, a state reason to go,

challenges and trials along the way, and a real reason to get to the destination (3). Because her mother

fears that grandmother is not well (a stated reason to go), Little Red Riding Hood (quester) sets off on her

journey to her grandmother’s house (place to go). She travels through a forest and meets a wolf with bad

intentions (challenge/trial); it is not until she has been trapped and eaten that the reader realizes the hidden

warning Perrault shares (real reason to go) which is, “Don’t talk to strangers.” *However, to think quest

literature can be defined simply by structure would be naïve. Foster explains that the quester usually does

not know that the journey taken is a quest (3). So, quest literature need not be epic in nature; a hero who

is determined to save a person/people is not required. Little Red Riding Hood, a young and inexperienced

girl, enters the woods to visit her grandmother not knowing that danger is near. Unfortunately, in

Perrault’s tale, her ignorance costs her her life. *Also note that that the real reason for the quest and the

stated reason are never the same. Foster explains “the real reason for a quest is always self-knowledge,”

and “the stated goal fade[s] away” (Foster 3, 5). Though Little Red Riding Hood understands that she

must visit her grandmother because mother wants to be sure that grandmother is doing well, she does not

understand that there is a different lesson to be learned in the end. In speaking to the wolf, she shares her

destination, giving him the opportunity to gobble her up, and she loses her life. Therefore, teaching the

reader to be cautious of strangers. So, the next time you pick up something to read, even something as

simple as a children’s story, remember that “when a character hits the road, we should start to pay

attention, just to see if… something’s going on…” (Foster 6).

Perrault, Charles. "LITTLE RED-RIDING-HOOD." Favorite Fairy Tales: The Childhood Choice of

Representative Man and Women. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1907. 87-91. Print.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/32389/32389-h/32389-h.htm

*Transition words

Single Paragraph Essay: Visual Example

from Little Red-Riding-Hood

SENTENCE

1

NAME

THESIS/TOPIC

CHUNK #1

2

BODY POINT #1

3

4-5

CHUNK #2

6

7

8-9

CHUNK #3

10

11

12-13

FINAL

14

PURPOSE/CONTENT

Charles Perrault’s beloved fairytale, “Little Red-Riding-Hood,”

is more than it seems; Perrault goes beyond a simple telling of a

children’s story to share the tale of a little girl who sets out on

an epic quest to her grandmother’s house.

Perrault’s story of a small girl cloaked in red easily fits the

structure of quest literature.

CONCRETE

According to Thomas C. Foster, the author of How to Read

DETAIL

Literature Like a Professor, there are five items needed for a text

to fit the quest structure: a quester, a place to go, a state reason

to go, challenges and trials along the way, and a real reason to

get to the destination (3).

COMMENTARY Because her mother fears that grandmother is not well (a stated

reason to go), Little Red Riding Hood (quester) sets off on her

journey to her grandmother’s house (place to go). She travels

through a forest and meets a wolf with bad intentions

(challenge/trial); it is not until she has been trapped and eaten

that the reader realizes the hidden warning Perrault shares

(real reason to go) which is, “Don’t talk to strangers.”

BODY POINT #2

*However, to think quest literature can be defined simply by

structure would be naïve.

CONCRETE

Foster explains that the quester usually does not know that the

DETAIL

journey taken is a quest (3).

COMMENTARY So, quest literature need not be epic in nature; a hero who is

determined to save a person/people is not required. Little Red

Riding Hood, a young and inexperienced girl, enters the woods

to visit her grandmother not knowing that danger is near.

Unfortunately, in Perrault’s tale, her ignorance costs her her

life.

BODY POINT #3

*Also note that that the real reason for the quest and the stated

reason are never the same.

CONCRETE

Foster explains “the real reason for a quest is always selfDETAIL

knowledge,” and “the stated goal fade[s] away” (Foster 3, 5).

COMMENTARY Though Little Red Riding Hood understands that she must visit

her grandmother because mother wants to be sure that

grandmother is doing well, she does not understand that there

is a different lesson to be learned in the end. In speaking to the

wolf, she shares her destination, giving him the opportunity to

gobble her up, and she loses her life. Therefore, teaching the

reader to be cautious of strangers.

CONCLUSION

*Transition words

So, the next time you pick up something to read, even

something as simple as a children’s story, remember that

“when a character hits the road, we should start to pay

attention, just to see if… something’s going on…” (Foster 6).