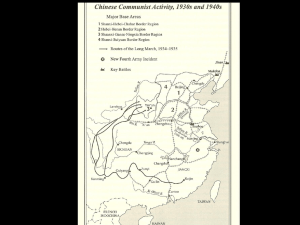

National Studies: China 1927-1949 The Nationalist Decade 1927-1937 I. Political, economic and social issues in the Chinese Republic in 1927 After 12 years of chaos under warlords, the people welcomed GMD and 3 principles of Sun. However, there were a range of complicated and difficult issues that needed to be addressed. Political Issues: No central government China’s elite in a political vacuum Instability from remaining warlords and Communists Warlords fought each other for dominance Economic Issues: Massive debt Economic stagnation Social Issues: Country was wracked by social and economic injustice Foreign control of infrastructure, foreigners occupied territory, foreign goods flooded the Chinese market, foreign law took precedence over Chinese law and foreigners controlled customs duty. This caused shame. 70% lived in dire poverty with crushing taxes imposed by warlords Abolition of the Confucian examination system destroyed Confucian values leaving. China was united in their demand for an end to the unequal treaties. Hostility from Japan II. The Northern Expedition and its impact Outline of Northern Expedition On 15 June 1926, Chiang was made Commander-in-Chief of Nationalist Army He issued Northern expedition to overcome northern warlords and unite all of China under the GMD Phase One Social mobilisation and genuinely revolutionary march stimulated mass involvement Began to alter long-standing relationships between workers and employers, peasants, landlords, army, Chinese and foreigners (Sheridan) Phase Two Military mobilisation, more like war than revolutionary process Unity achieved by force imposed by an agglomeration of warlords The revolutionary thrust was weakened by the joining of the warlords, who had different ideas and goals (Sheridan) The impact of the purge of Communists in Shanghai The Communist purge (1927) in Shanghai effectively divided China into two irreconcilable camps. Purges were repeated in every city under Chiang’s control like Nanjing, Hangzhou and Fuzhou. Dissolution of CCP Eliminated many of the most progressive activists and discouraged those committed to action for national welfare. Negative Impact of the Northern Expedition Overall, the second phase of the Northern Expedition had more impact – it sowed the seeds out of which the Nationalist regime would grow and become rank. By absorbing the conservative and militarised warlords, these groups had a high level of power and influence over the Nationalist regime, shaping it to their will and personal advantage. The warlords only paid lip service to the Government Future government weakened by warlord involvement in ruling Chiang blunted the sharp anti-imperialist policy that had characterized GMD since 1924 due to Russian influence as he rejected the Russians and the Communists, and Chiang’s bourgeoisie supporters got along well with the foreigners. Achievement Many of the warlords were under GMD and pledged to work for nationalist goals and principle. III. Imperialist powers also pledged to relinquish special privileges in power. Achievements and limitations of the GMD Government The Republican period was a period in which disorder and disintegration were at their maximum. (Sheridan) China was so mired by domestic troubles and beset by foreign invaders that some doubted that the nation had any future at all as an independent political entity. GMD ideology did not present a persuasive or enlightening analysis of China’s problems or a convincing method of solving them. The key factor explaining the failure of the Nanjing government to effect rural reform was that the government was essentially rural orientated, part of the bourgeoisie. The GMD could never make up its mind whether its revolutionary past should impel it forward to modernity, or its nationalist chauvinism carry it back to Chinese tradition (Fitzgerald). Social Problems The biggest social problem: low average standard of life. Did the GMD solve this problem? No. Little was done to improve the quality of the peasant’s life. The peasant majority suffered from harsh landlords, high rents, high taxes, high interests, primitive methods of agriculture and low production. Tough the National Economic Council was set up to develop industries and a law was passed to limit farm rents to 37% of a peasant’s crop yield. But this action was limited because too much of the government’s money was spent on the army or disappeared into the pockets of corrupt officials. Few improvements reached the rural areas. The industrial workers also had few rights, long hours and low pay. The peasantry and the urban workers remained downtrodden and poverty-stricken. Sun’s party had come to power with the support of the wealthy and the powerful – bankers, businessmen, landlords, and local administrators. He could hardly afford to offend these people by pushing through reforms which would weaken their power and influence. So the expected social revolution which often follows a political revolution did not come with Chiang’s government. Lack of modern infrastructure Did the GMD solve this problem? To some extent - the new government devoted a great deal of energy to developing the infrastructure to servicing a modern state. The railroads were expanded, but this was mostly designed for military use. The China Aviation corporation was established and post offices and telegraph lines were erected. School enrolments rose from 13 million to 23 million The government made a serious attempt at increasing agricultural productivity and sponsored research into new varieties of seeds, pesticides, fertilizers and new irrigation systems were developed. mostly in the field of communications. Railways were extended, roads built, and in the provinces these changes, where the Communist war was not a complicating factor, brought certain benefit. However, these efforts were hampered by a lack of money as 87% of GMD treasury was spent on the military, mostly in an effort to exterminate the CCP. Imperialism from Westerners Did the GMD solve these problems? To some extent; the GMD abolished around half the foreign concessions and regained control of customs and postal services. However, foreigners still controlled a lot of trade and industries; major powers still had concessions. Chiang was able to reclaim half of China’s foreign concessions, and by 1933 China had control over her own customs duties. However, he was limited because he was getting support and financial backing from the foreigners. Imperialism from Japanese - Encroachment by the Japanese on Chinese territory Did the GMD solve this problem? The Nanjing government under Chiang did not attempt to resist the Japanese encroachments by force, Chiang believed that national unity was a prerequisite to effective resistance, and that national unity first required the destruction of the Chinese communists. The Japanese were already dominating the vast and rich area of Manchurian; they were soon to annex it outright, or rather to cover such an annexation in the discarded robes of the Manchu Dynasty. They then invaded Jehol province, without any effective resistance by the Nanjing government. Later still they virtually detached North China from the control of Nanjing, used the Settlement at Shanghai as a base of attack, stationed ever-larger forces in Chinese cities such as Tientsin and Tsing Tao, at last openly invading the whole country. Shanghai was made into a base for Japanese aggression into the south. This was a greater loss of territory and power, of prestige and resources, than the Empire had suffered in a hundred years of decline. During this long and cumulative series of aggressions, the Nationalists of Nanking yielded step by step, without resistance, without listening to the clamour of the people, the indignation of the intellectuals, or the appeals of those provinces which they abandoned. Policy: ‘internal pacification before resistance to external attack’ ineffective because there was no internal pacification and external attack became ever more serious. Social disunity Did the GMD solve this problem? No, it was unable to enthuse the population for the regime. Nobody paid much heed to the Three Principles; in fact, Chiang had a strong Confucian strain. The New Life Movement, a propagandist action to reassert Confucianism and Chiang’s power, failed dismally. It tried to enthuse the nation behind its leader. Economic Problems Galloping inflation and inefficient money management Did the GMD solve this problem? No. Though the GMD did establish some banks, they did little stimulate the economy overall – until the peasants, which composed 70% of the population, broke out of economic stagnation, any changes would have little effect. The government overtaxed the population and never learned to balance its budget. It made up the shortfall by selling government bonds, which absorbed a great deal of capital that might otherwise have gone into productive investment. The government attempted to remedy this by printing more money, which led to inflation. Political Problems Ordinary people unable to self-determine their lives though democracy Did the GMD Solve this problem? No. Over time, Chiang was able to manipulate power and structure of GMD to become the unchallenged leader of a one party state. The GMD took no realistic measures to train people in self-government, which would have eliminated the justification for its own monopoly for political power. There was intense political repression on the part of the government. The chief goal of the government seemed to be to hang onto power, and repression of the government was used to achieve that goal. There were assassinations, illegal arrests, summary executions and censorship. The Press Law of 1930 allowed Chiang to ban 450 literary works and 700 other publications. By 1934, thousands of university students had simply disappeared. Chiang cultivated a highly organised and strongly ideological group who enforced his power, called the Blue Shits, who liquidated those who opposed the state, the party and Chiang himself. They were Chiang’s own police force and terrorist organisation. Personal relationships determined most of what got done. The Communists were undermining the authority of the GMD Did the GMD solve this problem? No. They were never able to crush the communists. The government launched a series of extermination campaigns in 1930 to wipe out the Communists. However, due to the success of the Long March and the Yanan Soviet, these attempts came to nothing. Huge sums of money were wasted on vain attacks on the Communists. Thus the communist resurrections both inhibited the government from resistance to foreign aggression and from internal reform. The Communist insurrection could have been contained, perhaps subdued, if the government, in the rural areas which it fully controlled – the vast majority of provinces – had put into effect a real policy of land reform. The reduction of rents, remission and honest collection of taxes, measures to provide the peasant with loans at moderate interest, some resettlement and some redistribution of the land, all measures which elsewhere would have been the surest shield against Communism, all these were possible, quite practical, but neglected (Sheridan). Each of the provinces was independent, with old warlords still retaining much of their power. Did the GMD solve this problem? Chiang’s power was frequently challenged, as some warlords still retained much of their power. Probably the most important feature of the five-power government was that it was virtually all on the national level, with little relevance or effective authority at the local level. The National Government never developed a large enough civil service to run the country. Chiang had to allow warlords and governments a lot of control over local areas. Less than half the provinces had established regular party committees. The decline of the party’s organisation rendered it ineffective as a vehicle for national political integration. The party was neither inspired nor dedicated (Sheridan). The party purge at the time of the split with the Communists in 1927 had eliminated many of the most progressive activists and discouraged those committed to action for national welfare. Chiang himself admitted (as quoted in Sheridan) that it is ‘impossible to find a single party headquarters which administers work for the welfare of the people’ and that the party was filled with ‘corruption, bribery and scrambling for power’. Fitzgerald notes that ‘the frequent quarrelling between the leading members of the party, the arbitrary arrests, exiles and executions of opponents of the Generalissimo, showed plainly the real character of the regime.’ Conclusion The thing ate out the heart of the Nationalist movement was the lack of any real satisfying and inspiring ideology. The party’s policy of Nationalism was not enough, given the continuous yielding to the Japanese. Democracy failed. People’s livelihood was abandoned. To what extent, to what vision of the future, the GMD progressed, no one really knew. The GMD was still to a large extent the prisoner of its own past. The attempt to modernize China without interfering with the land system, the endeavour to fit some rags of Confucian doctrine to a party dictatorship, to deny the practice of democracy yet to continue preaching it, to proclaim and teach nationalism yet continue to yield to the Japanese – this medley of contradictions could not form a coherent policy which would earn support. The lack of vision meant that the GMD was susceptible to selfish ambitions, corruption and nepotism. Not many of its members cared about the good of China. No one knew what the ultimate shape of the government’s future. The short term prospect, the rewards and spoils of office and the ambition of high command were eagerly sought and fiercely contested. Chiang never controlled China; he could not prevent the Japanese infiltration, he could not crush the Communists, he could not discipline and keep loyal generals and ruled only by playing one faction of the GMD against another. The internal situation did not seriously deteriorate, but it did not improve. The external situation changed for the worse. Instead of the limited encroachments of the western powers, anxious for trade rights, but not at all anxious to take over the immense task of governing China – in place of these gadflies, the GMD faced Japan, who did in fact intend to conquer China and incorporate the while empire into her own. The GMD never faced this danger or made a policy to meet and counter it. Immanuel Hsu: ‘Beneath the veneer of progress lay serious and fundamental problems of social and economic injustice and the chronic ill of deficit spending.’ The Rise of Mao Ze Dong IV. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ideology CCP ideology was transformed from Marxism to Maoism as the CCP adapted Communist ideas to suit the difficult situation in China, as well as the practical demands of the time. Chinese Communist ideology became less urban-orientated and more ruralorientated. Marxism Karl Marx, on whom Communism was based believed that change in the way a society earns a living (the mode of production) fives rise to new classes which struggle against the most powerful to gain power and a new organization of society. For instance, the French revolution was the growth of middle class which overthrew the ruling elites. Due to the new class of city workers as a result of the Industrial Revolution, the same thing will happen as the city workers will overthrow the bourgeoisie to establish a dictatorship for the proletariat. Change from Marxism to Chinese Communism The influence of the Comintern gradually decreased. Li Lisan, the leader of the Communist Party until 1930, supported a proletariat revolution. He was replaced by Wang Ming, the head of the Russian Returned Students leadership. A CCP strategy of armed uprisings in urban areas in the period after 1927 failed to arouse the proletariat against the GMD and resulted in a further weakening of the party. This suggested that a better strategy would be centred on the peasants. Mao and others were experimenting with a new strategy of developing a rural base, spreading propaganda amongst peasants, instituting land reform and creating a guerrilla army Lenin adopted Marxist ideology to suit China. Rather than the city workers overthrowing the bourgeoisie, he advocated that the middle class, peasants and city workers combine to overthrow the warlords. The Chinese Communists gradually stressed the role of the peasants more and more, under Mao’s guidance, which was effective as 70% of the population consisted of peasants. Mao took strong measure to ensure the party stayed close the people and did not develop an elite V. Rise and consolidation of Maoism Mao realised the revolutionary potential of the peasantry and advocated a rural strategy. As the successes of the Jiangxi Soviet and the Communists under Mao rose, so did his ideology (Maoism). Characteristics of Maoism Centralised organisational control and strong state power Continual struggle and conflict against conformity Creation of a classless society The remoulding of ideological mistakes through self and group criticism Creation of a welfare state to promote social order Creation of economic stability Belief in the superiority of the human spirit over machines Value of self-reliance rather than dependence on the state Anti-intellectualism Superiority of rural values over urban values Distrust of individualism and respect for the collective spirit Guerrilla warfare The Jiangxi Soviet Mao’s guerrilla army concentrated in one area, which led to the formation of the Jiangxi Soviet. The success of the Jiangxi Soviet contributed to the rise and consolidation of Maoism. For some years the Chinese guerrilla Communists were fortunately for themselves so cut off from all communication with the world that they could not receive even censure from Moscow: they had to think for themselves. This allowed the development of some key Communist ideas and strategies that contributed to the Communist victory in the Civil War. It was during his time at Jiangxi that Mao experimented and formulated some of his key ideas. May and Zhu De, the leaders, instructed their army in guerrilla tactics and political education. They saw that the combination of developing a unified and disciplined Red Army with increased peasant cooperation was the key to political mobilisation. In Jiangxi, between 1928 and 1934, he created a model of an agrarian revolution that was to win China for the Communists. The reasons for the communist success in Jiangxi Soviet were: The popularity of land policies such as abolishing rents, reducing taxes and establishing peasant cooperatives Women’s policies such as outlawing foot-binding, prostitution, child slavery and forced marriages Banning of begging, gambling, opium smoking Good relations were established with the people Achievements of the Jiangxi Soviet Mao and other leaders began to develop a winning formula for their Communist revolution: political economic work with the peasants, and a Red Army skilled in mobile warfare. Mao had succeeded in forging links between his Red Army and the peasants so that his ‘fish thrived in the peasant sea’ (Mao). They were determined to prove themselves the friends of the peasants, and they revenged themselves upon the peasants’ traditional enemies, such as landlords and GMD officials, who were hunted and slain. This won them the support of the peasant population. The peasants gave them information about the movement of the GMD, denied such information to the latter, fed and carried for the CCP, vanished from the GMD The CCP were able to test their ideas and methods in the Jiangxi, which established a protocol of how to spread communism throughout China successfully During 1931-1933, leadership was swapped from Mao to Zhou En Lai and the Returned Russian Students. The CCP’s lack of success after this highlighted the importance of Mao to the party, an important revelation that shaped the development of Communism in China Mao’s time at Jiangxi proved to him the importance of the peasant’s to the revolution The Communists led many insurrections in the cities, which failed due to the apathy of the proletariat. In spite of official party statements, it became obvious that the real power lay within the successful peasant bases in the south rather than the cities. They developed a soft-footed approach, such as being nicer to the wealthier peasants The Communists, while still in Jiangxi, issued an empty and propagandist declaration of war upon Japan. Empty, because the Communists were nowhere near the Japanese. Propagandist, because they wanted to come forward as the champions of the patriotic movement. This worked reasonably well, increasing the favour of the Communists in the eyes of almost all Chinese classes, including the intellectuals. The Communists abandoned their extreme anti-warlord approach, instead attempting to unite all classes against the Japanese: ‘Chinese do not fight Chinese’. Mao’s major problems between 1928 and 1931 Struggle for survival in a harsh environment Constant threat from GMD armies Criticized by CCP for his flexible approach towards party dogma How did Mao win the support of the peasants? He refined a method of land management that benefitted the peasantry He attacked age-old abuses, such as foot binding Peasants were allowed to cooperate with the marketing of farm produce How did Mao develop an effective, highly disciplined army? He promoted the ‘unity of officers and soldiers’ He promoted political education He promoted literacy among the soldiers The troops were encouraged to help the peasants with harvesting and irrigating He had in instinctive knowledge of how to motivate men Encirclement campaigns Chiang attempted to eliminate the Jiangxi Soviet with five encirclement campaigns between 1930 and 1934. Mao’s guerrilla fighters successfully used the tactic of luring the enemy deep into Communist territory before attacking and picking of the enemy one by one. VI. The Long March and its political and social consequences Summary of the Long March Long March was necessary because of the success of the 5th encirclement campaign by the GMD. In preparation for the Fifth Encirclement Campaign, the GMD troops built 7000 concrete blockhouses linked by barbed wire fences around the Jiangxi Soviet. Their intention was to starve the Communists of all supplies and slowly reduce the area they controlled. The Communists, under the detrimental advice of new Comintern agent, Otto Bruan, decided to fight a series of conventional battles. Mao was expelled from the Central Committee for opposing this. Eventually, the Communist forces had to break out of the GMD stranglehold – the Long March. The Long March began in October 1934 and was completed by December 1935. Of the 100 000 who began the journey, only 8000 completed it. The marchers took just a year and covered 9600 kilometres; they crossed 18 mountain ranges and 24 rivers. They passed through 12 different provinces, occupied 62 cities and broke through enveloping armies of 10 different provincial warlords and eluded, defeated or outmanoeuvred. Some important elements of the Long March They crossed a huge area of central China They endured conditions of incredible hardship They achieved some amazing feats They encountered great problems finding food Political and Social Consequences The Long March allowed the CCP to survive and continue their revolutionary work; its success meant that China’s history for the next decade and a half would be dominated with the political tension between the Nationalists and the Communists, which existed even during the Sino-Japanese war. Achievements of the Long March It helped to perfect the guerrilla tactics of the Communists and the disciplined resolve of the troops. Guerrilla warfare is effectively summed up in Mao’s catchphrase: ‘The enemy advances we retreat; the enemy halts, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue’. The communist forces came into contact with peasants in remote areas and their behaviour was thought as favourable compared to the GMD The delegates at the Zunyi Conference of January 1035 had decided that Mao’s guerrilla tactics and his desire to march North to defeat Japan should be endorsed. During the Long March, especially as a consequence of the Zunyi Conference, Mao was able to ascend the hierarchy to become leader of the Communist Party. He forced the abandonment of Russian influenced policies in favour of his peasant based socialism. The seeds of communism were sown in the minds of the 200 million Chinese in the provinces they passed through. They often left cadres to further the education of the peasants Despite enormous Red Army loose, it created an invincible mythology which was to have enormous propaganda potential once Mao reached Yanan The Long March located the CCP in the northern area of China from where they could oppose the steady encroachment of Japanese forces into China. foo Resistance to Japan I. Military, social and economic impact of Japanese Invasions from 1931 Overview The Japanese offensive produced the most effective national unity that China had known in a generation, at least temporarily (Sheridan). Neither party publicly repudiated the United Front until the end of the wear in 1945, but actual cooperation between them was minimal and short-lived. By the end of 1938, the Japanese had stopped their advance. They then controlled most of northern China and the eastern coastal regions extending inland as far as Hankow in the centre of Eastern China. To administer this enormous area, the Japanese developed puppet Chinese governments. They then conducted limited troop operations, bombed Chungking and other cities and waited for the Chinese Government to collapse. The Japanese made all the mistakes which the most fervent Chinese patriot could have hoped for. They advanced far into the interior, only holding key cities and lines of communication. Though they sought to destroy the field armies, they neglected the beginnings of guerrilla resistance. They allowed their army to treat the Chinese brutally. They alienated all foreign sympathy by open disregard of their rights of foreign nations and ill-treatment of their nationals. They could not have adopted policies more calculated to rouse the Chinese people to enduring opposition. The objective of the Chinese behind Japanese lines was not to seize railroads or cities, which they obviously could not hold against Japanese power, but to compel the Japanese to spend more and more energy and treasure to defend their holding, and simultaneously to deprive the invaders as much as possible from profiting from their occupation. In gaining these ends, the Communists were superbly successful. Military Impacts Brought temporary unity Chiang’s government found it impossible to exercise effective command over the Communist armies. The two parties operated in different regions, followed different policies, and generally functioned separately – particularly after troops of the two camps clashed in early 1941. Social Impacts In their swift thrust into China, the Japanese conquered the cities and the chief lines of communications between the cities. The conquest of the rural areas between the cities and railroads was a much slower task because there were few roads of facilities for Japan’s motorized army. Japanese brutality virtually forced the peasantry to vigorous resistance. Villages were razed, young men were selected form the population for public execution, and women were maltreated. These campaigns subjected the peasants to such indiscriminate terror that they had little choice by to resist; non-resistance in no way assured security: “kill all, burn all, destroy all.” These policies transformed patient farmers to determined resistance fighters. The Government did not collapse but wartime conditions magnified some of its weaknesses. (Sheridan) Economic Impacts The Japanese invasion had a significant impact on the economy of the Japanese themselves as it drained unsustainable amounts of money and resources. Conclusion The eight years of warfare created conditions that undermined Chiang’s Nationalist Government, exposing its weaknesses, and provided an opportunity for the re-emergence of the communist party. The Nationalist government, form the end of 1939, never made any further military effort to recover lost territory. It sat and waited for the world war to determine the nature of the result. The Communists set about the infiltration and organization of the so-called occupied areas, imbuing them with Communist ideology. II. Differing aims and strategies of the GMD and CCP toward the Japanese Invasion of China The Xian Accident and the United Front The Xian Accident of December 1936 led to the Second United Front. When Chiang flew to Xian in Manchuria to order his commander, Zhang, to attack the Communists, Zhang mutinied and held his leader captive. He was then forced to negotiate with the Communists, and eventually agreed upon a Second United Front. The Xian incident contributed to the long term success of the Communists, though it had the appearance of a short term concession. Under the conditions of the Second United Front, the Communists agreed to abolish its independent state, suspend its land distribution and confiscation and abolish the name of the Red Army and conceded to the power of the GMD. Though these appeared to be big concessions, there were more often nominal than real. In fact, the power was with the Communists: it was Chiang who had yielded, and the Communists who forced him to overthrow the policy he had followed for ten years, and adopt that which the Communists had made their own. By these actions, the Communists henceforward had the fascination of the educated class. It appeared they sacrificed their own interests for the good of China. This appearance was valuable and won them wide support. The reward in public esteem was significant the CCP was credited for ending the civil war and compelling the government to resist Japan. Hitherto, the CCP lacked the support of the great mass of the educated class. Now they won back all and more. The Nationalists Aims and Strategies Chiang chose to trade space for time. His strategy was to retreat deep into China’s vast hinterland, yielding territory to Japan. The invaders would soon reach the limit of their absorptive and administrative capacities; they did not have the men or resources to maintain form control of a huge occupied territory or to keep their lines of communication secure. Given the disparate regional character of the armed forces, and their inferiority to the Japanese in technology and heavy armaments, the Chinese Government armies could not effectively employ positional warfare to resist the modern armies of Japan. While the Japanese struggled with those problems, the Chinese would have time to build up their strength and await the international assistance that Chiang expected would eventually come. After 1941, the Chungking government increasingly counted on the US to defeat Japan, and, in anticipation of a future war with the Communists, sought to conserve its own best forces. The effect of these aims and strategies The government was mostly on the defensive with the Japanese, and this passivity corroded morale in the government armies. This made it easier for them to be defeated, later in the Civil war. They did, however, keep the Japanese tied down. In short, from 1938 to 1945, the GMD government as in western China, substantially cut off from the rest of the country and the rest of the world, dominated by its most reactionary elements and plagued by galloping inflation. Chungking in the Sichuan of the Western part of China became the capital city. They came to depend heavily on the landlords of interior China – particularly in Sichuan – a notoriously conservative group. This dependence, and the fact that the government felt threatened in warlord territory, strengthened the reactionary elements in the government, lessening its chance to gain popular support. The government failed to develop revenues sufficient to meet wartime needs, and therefore had no other recourse than inflation as a means of paying for the war. The inflation impoverished the middle class and encouraged corruption and speculation of all sorts. The GMT government had, in many instances, fled from occupied areas, leaving a government vacuum. Why did the GMD Decline so Drastically during the Years? The Army The Generals The army was disunited – many owed loyalty not to Chiang, but to their warlords. Since their power depended on the strength of their army, the former warlords were reluctant to risk combat with the Japanese. Between 1941 and 1943, 69 generals to 500 000 soldiers across to the Japanese. The Officers Poor calibre with little training General Wedemeyer (US commander), the officers were ‘incapable, inept, untrained, petty and altogether inefficient’. They brutally treated their own men Corruption, such as stealing military supplies for personal use The Enlisted Men Treated poorly Richer men bought their way out of conscription Malnutrition Insufficient weaponry Many conscripts died before they even reached their units Moral was low and desertion was very high The Peasants Had to bear the conscription burden as well as the increased taxes of the Nationalist Government The peasants had to personally deliver their grain to collection centres, which could take up to four days travelling. This new procedure increased the peasants’ tax rate and brought them into closed contact with brutal officialdom, and heightened their resentment of the government. The government forced the peasants to sell their grain at an unfair and low price Massive amounts of peasants were conscripted to work on government projects The Economy The urban middle class, who had been the main supporters of the GMD, were being impoverished by spirally inflation – the government had simply printed more money to finance the war. Political Repression The conditions of the war naturally generated discontent and criticism of Chiang’s government, to which he responded by becoming increasingly repressive. Conclusion The years of war had a most corrosive effect on the Nationalists: the army was demoralized, the peasants overburdened and the middle class ruined by inflation. The Communists Aims and Strategies A significant aim was to gain popular support while the GMD was tied down by the Japanese. It was in the rural areas, beyond the Japanese, that the Communists thrived. They organized local and regional enforcements that exercised political authority, collected taxes, administer public services, and generally exercised all the normal prerogatives of government, including defence. These were called antiJapanese bases. The juxtaposition of Japanese conquests and Communist bases was comparable to a checkerboard on which the Japanese controlled all the fid lines with cities and the points of intersection and the Communist led resistance gradually expanded to till all the squares between the lines. These anti-Japanese bases were united through the CCP. (Sheridan) The Communists saw the way to ultimate triumph through the disasters which war must surely bring to China. They thought that they could afford to be the allies of the GMD because that party would perish and the Communists would be their heirs (Fitzgerald). Effects of CCP’s aims and strategies The Communists gained the enthusiastic support of the mas of the Chinse peasants in North China. They achieved this backing by meeting the local, immediate needs of the peasants through reformist and radical social policies and by providing leadership for the defence of peasant communist ties against the Japanese. Angry peasants formed resistance groups to defend their local communities and the Communists provided the weapons, training, general assistance and leadership they needed. The Communists also linked one local group to another through party communications and organization into what gradually emerged as an antiJapanese-war base. Units of the Red Army tried to fill the political vacuum and organized new of governments and devised resistance measures. The peasants intensified the anti-Japanese struggle, provided regional government for peasants, and assumed the overall leadership in both government and resistance operations. The CCP brought many benefits to the peasantry. Anti-Japanese activity was only part of the Communist’s appeal. The other side was their social policy and program: land redistribution. The Communists introduced a new tax system that favoured the poor, but that was by no means confiscatory for the rich. They gave the peasants a voice and a part in the political system. The social reforms of the Communists marked a radical change in rural China. These changes signalled the beginning of a social revolution. Communist wartime propaganda nurtured a national consciousness, and thus fostered national integration. The Communists tailored their policies to the areas they controlled. In areas mobilized by Japanese brutality, anti-Japanese leadership was the chief Communist attraction, though effective resistance necessitated the kind of cooperation between government and people that social reforms could foster. In other areas, social reforms were the major appeal, and were used to involve the peasant in the anti-Japanese resistance movement. (Sheridan) In short, in every way possible, the Communists attempted to help the mass of poor peasants, to persuade and educate them, and in the process to gain their support. Tapped into patriotic sentiment in the war with Japan. The obvious success of the Communists in organizing guerrilla warfare and resistance in the north and east contrasted with the failure of the GMD in the later years to maintain the spirit of resistance of 1937 and 1938. Communist agents infiltrated the country areas, won the confidence of the peasant leaders and gradually established guerrilla bases. During the eight years of war, the Red Army grew from 90 000 to 1 million with 2 million peasant militia. Of the 1500 engagements fought by the Japanese troops in China, 75% were against Communist forces. Why were Communists so successful? The Army The Generals Mao was supported by talented generals who had shared the common hardships of the Jiangxi Soviet and the Long March, like Pan Duhuai, Lin Biao and Zhu De. The Officers The officers were promoted by merit rather than political influence. The Communist officers had the respect of their troops They were young, energetic and devoted They wore no badges of rank and shared the same food and living conditions as their men They imposed no brutal punishments yet there was superb discipline The Enlisted Men Morale was sustained by a busy but varied daily routine that aimed at producing committed Communists as well as good soldiers. Great emphasis was placed on political education and literacy The Peasants The Communists were able to win the peasants’ wholehearted support. Nationalism The Communists used the Japanese invasion to inspire nationalism. Their association with this nationalism increased their popular support. By stressing national salvation rather than social revolution in certain areas, the Communists were often able to win the support of small landlords. Political and economic Policies Land Reform Softened harsh land laws that alienated richer peasants However, did proceed with land redistribution Conclusion At the conclusion of the war, the Western powers put the GMD, who they saw as the legitimate party, in government. However, the Chinese saw the GMD as a corrupt dictatorship. The Communists were the liberators of the Chinese of the north. To deny them the cities they had so long encompassed would mean civil war, for they would never accept this decision. The sense of public opinion was so against civil war and the reoccupation of the North but the GMD so inevitable mean civil war that the force of opinion swung over strongly to the communist side. Many who did not approve at all of Communism felt that this time, the Communists were being provoked and attacked. Most of the educated in China wanted a coalition government which would eliminate the worst features of the GMD and restrain the most extreme manifestations of Communist revolution. Communist China had arisen during the war and GMD China had withered in that wintry climate. The Nationalist government degenerated into a brutal dictatorship and its army decayed through inactivity. During the same time, the Communists prospered. III. Role and impact of the leadership of Mao Zedong and Jiang Jieshi Jiang Jieshi Jiang’s refusal to cooperate with the Communists in a united front against the Japanese caused criticism of the Nationalists and exacerbated their decline in popularity Once the Second United Front was formed, however, Jiang took an active role in the war against Japan. Through the grim years of 1938, his leadership was inspirational. At his bidding, entire factories were moved hundreds and sometimes thousands of kilometres away from the Japanese threat. Universities were relocated to free China. Yet the withdrawal from China’s major cities – the power bases of the GMD – subjected the Nationalist government to strains Chiang was unwilling or unable to overcome, which led to increased political repression. Chiang’s insecurity led to his under-use of his more able generals, such as Ba Chungxi. Chiang feared that military success might encourage such men to challenge him. Mao Zedong Maoism, especially guerrilla warfare, prospered and the Communist’s popularity grew during the Sino-Japanese war. Mao was able to fully command his generals. Mao’s two guiding principles had significant impact. These were to concentrate the Red Army against the Japanese and to rouse the masses to support the Communists. Political Reform Adding to Communist ideology, Mao appealed to the Three Principles of Sun. In leading the fight against Japan, the party claimed it was carrying out Sun’s principle of nationalism. By its moderate land reform, the party was implement People’s Livelihood. Mao proposed that Sun’s principle of democracy be realized by a democratic government open to all classes that opposed imperialism. Mao ordered elections in Communist base areas that allowed entry from everyone, including rich peasants and landlords. Imposed the Zhengfeng, or Rectification Movement, which was an educational program of study-group discussion and self-criticism in which party members were brainwashed with Maoism. This contributed significantly to the strength of wartime Communism by increasing Mao’s prestige and by ensuring a strong commitment to a cohesive set of goals and values. IV. Political and social significance of the Yanan period Yanan was situated in the Shenshi province Yanan was seen by many Chinese as the chief symbol of resistance to Japan. During the anti-Chinese war, CCP organizations and territory expanded steadily and membership in the CCP mushroomed. (Sheridan) It was seen was a beacon of patriotism and social justice. The Triumph of the Chinese Communist Party V. The Civil War and military success of the CCP Overview It is difficult in retrospect to see how the civil war could have been avoided. (Sheridan) The Americans attempted to mediate between the CCP and the KMT but failed dismally. The Americans continued to provide military aid to one party in the negotiations, the GMD. They ordered the Japanese to surrender only to the Nationalists, and militarily supported the Nationalists. The GMD had full advantage at the beginning. Government troops outnumbered GMD troops four or five to one, and they had much better weaponry. During the two years following the cessation of negotiations, however, relative military strength had shifted in favour of the Communists; communist ranks grew while GMD armies shrank, and the Communist acquired mountains of weapons and material from their defeated enemies. The erosion of government strength and the concurrent expansion of the Communists began to depart from their reliance on highly mobile, limited engagements, and increasingly they challenged government armies in positional battles. Sheridan points out that the desire of many Americans to view the civil war purely in military terms seems to derive partly from a post-1949 reluctance to acknowledge that Communists can have genuine popular support. The Course of the Civil War Stage One First year, 1946-1947, the Nationalists were successful on all fronts, even capturing the Communist wartime capital, Yanan. The lightly armed Communists were in full retreat before Chian’s vastly superior fire-power. The Nationalists captured much territory. Mao reverted to guerrilla tactics. Stage Two Later years, from mid-1937 to 1948, the Communists launched an offensive that brought striking success in Manchuria, Shandong and Central China. Victory in Manchuria in 1947 By January 1948, the Communists had become strong enough to launch a fullscale positional warfare VI. Defeated the nationalists at the battle of Huaihai, which broke the Nationalists Reasons for the Communist victory The CCP were more successful in tailoring its policies to win civilian support, particularly rural areas. In sum, Communist victory was built on the basis of political and military organization of the anti-Japanese bases, and the legitimacy and moral authority derived from honest government and effective action against eh invader. After 1945 that legitimacy and authority continued because of the memory of the Communists’ wartime achievements and because of their accelerating program of social revolution based on the poor peasants. Popular Support Communist policies in the Sino-Japanese war showed the peasants that the wartime Communist administration was the best government they had ever known. The Communists continued the practices during the civil war that had earlier elicited popular approval: soldiers did not abuse civilians; the paid for what they used; troops helped the peasantry when the opportunity or need arose. Wherever Communists acquired territorial power, they instituted honest government and a series of political and economic reforms that benefited the peasants. The Communists also won over the intellectuals when they resisted the Japanese. The aid of the Americans to the KMT also smacked of imperialism, and the CCP resistance to this gained the support of the intellectuals. Marxist-Leninism also had its attractions for the Chinese intellectuals. Acceptance of Communism seemed to imply that China was moving ahead in the march of history, jumping ahead of all those nations that had for years arrogantly asserted their own superiority and China’s backwardness. The Communists also won over some of the merchants. Many in the middle class were aware the Communists had demonstrated their capacity to maintain economic stability and order on a regional level, and therefore might be expected to do it on the national level. Communist rule, then, seemed to promise something for everyone, the best of the real available alternatives. It is clear that a host of factors went into the Communist success: Communist organizational abilities, the military talents of the Communist generals, the attractions of Maoist ideology, the disastrous effect of inflation on the KMT and its supporters, the assistance rendered by the Russians in aiding and arming of the Communists in Manchuria, the political perspicacity of Mao and his associates, the short-sightedness, arrogance, incompetence and dishonesty of so many KMT leaders. But the central factor was unquestioningly the mobilization of vast numbers of Chinese, primarily peasants, into new political, social, economic and military organizations, infused with a new purpose and a new spirit. This mobilization largely accounted for the Communist victory, buts its significance went beyond that. It marked the beginning of the reintegration of China into a modern nation. Military successes Military strength in guerrilla tactics Highly disciplined Red Army won civilian support tired of rape & plunder of traditional armies Leadership Communist leadership was excellent from the top to the bottom. Zhu De and Mao carefully dealt with military realities and gave no weight to considerations of prestige and face that often guided Chiang. Other commanders, such as Lin Biao, Peng Duhuai and Liu Bocheng had all faced the hardships of the Jiangxi Soviet and the Long March, so there was a strong sense of camaraderie. (Sheridan) Communist field commanders were selected on merit, and given wide latitude to use their own judgement. They generally waged bold, aggressive and sometimes brilliant campaigns. (Sheridan) There was a continuity of command and a willingness to work for the common good The Communist commanders had more flexibility in the field Strategy Mao developed a clear and practical long-range strategy that put into effect a fast, mobile warfare aimed at the destruction of KMT armies rather than at the seizure of territory. Soldiers – High Morale Communist soldiers were well cared for, well trained, thoroughly indoctrinated about the need and purpose for struggle. Caring officers shared the soldier’s food and living conditions The intelligent Communist strategy of fighting only when success seemed assured cultivated a feeling of victory among the Communist soldiers, and stimulated a spirit of boldness and offense that contrasted vividly with the defensive spirit of the government units. Friendliness and support of the civilian population There was a democratic movement within the army as soldiers were invited to elect committees. Intelligence and Civilian Support Communist spies hampered the Nationalist Army and supplied vital information. The support of the civilian population ensured constant flow of information about nationalist troop movements. Political Success By their energetic conduct of the anti-Japanese war and by their land reform policies, the Communists established their moral authority over the peasants of North China. The party encouraged the destruction of landlord power. The fundamental social and political relationship of the Chinese villages was remoulded, and the peasants began to exert control over their own lives. Failure of the GMD During the Sino-Japanese war, the GMD’s passivity towards the Japanese steadily alienated the Chinse people. Corruption, political repression and inflation estranged the intellectuals and the urban middle class. The GMD elite treated the peasants with incredibly callousness. Lack of popular Support Not only did the KMT brutally treat the peasants, they alienated the intellectuals. The KMT offered them little more than a return of a tradition that they had long ago rejected as sterile and irrelevant to the modern world. The most appealing aspects of the KMT – its supposed commitment to constitutionalism, democracy and Westernization – were so flagrantly violated in practice that they had little positive effect on intellectuals. It was impossible to crush the Communists without the support of the common people. Chiang: ‘most people in society attack the party unsparingly even viewing party members as offenders against the state and nation.’ Leadership KMT generals were commonly chosen on grounds of political loyalty to Chiang, and many who qualified on this basis demonstrated professional mediocrity or outright incompetence. (Sheridan) The generals were reluctant to cooperate with one another, and many of the generals were corrupt. Nationalist commanders were more concerned with their own personal interests than the welfare of the army as a whole. The jealousies that had split the Nationalists during the Sin-Japanese war continued. Chiang himself admitted that at all levels of command, most feign obedience to their superior’s orders, sometimes not implementing them at all with the result that he value of the order is completely lose. Strategy Chiang gave no interest for following a strategic plan (Sheridan) but seemed obsessed with the seizure and retention of cities, even where Communists had the surrounding countryside. Ineffective use of air force, which could have given the GMD an advantage The GMD favoured defensive tactics, which did not work. The government wanted to keep a tight leash on its troops so that they did not defect to the CCP out fighting in the countryside. Demoralized Soldiers The GMD soldiers were treated with utter disregard for their health, their attitudes and their lives. The soldiers were inadequately paid and fed; training was poor to non-existent, discipline was bad; the rank and file did not know what they were fighting form and thus saw no reason to fight. Most of the soldiers were conscripted and therefore were heavily resentful about fighting. Many recruits died before they reached training camp. The soldier’s had low combat skills Many soldiers defected to the Communist side. Political Failure During its seven years of retreat in south-west China, the Nationalist regime became demoralized; inflation was rampant, corruption, rife The party had become more dependent on its more conservative elements Inflation was out of control Urban discontent – angry workers combined with students and intellectuals to protest against the GMD The government continued to favour the landlords against the peasants. Conclusion There were sound military reasons for the Communist success and Nationalist failure, but the fundamental reason was political. The Communists won the hearts and minds of China’s people, infusing their armies with purpose and spirit, and presenting a vision of the future that appeared even to the urban middle classes. On the other hand, the Nationalist regime alienated all sections of Chinese society, even their former supporters in the great urban centres, but their incompetence, corruption and brutality,