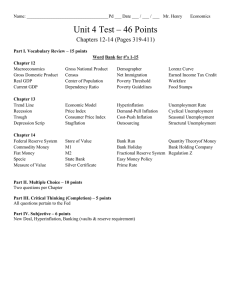

Business Cycle, Inflation, Unemployment: Definitions & Controls

advertisement

THE BUSINESS CYCLE: INFLATION AND UNEMPLOYMENT Definition, Types, Causes, Effects and Controls The Business Cycle • The term business cycle refers to alternating increases and decreases in the level of economic activity; sometimes extending over several years • Individual business cycles (one “up” and one “down” period) vary substantially in duration and intensity. • All business cycles show four phases: peak, recession, trough, and recovery • At the end of economic expansion, business activity reaches a peak. At the peak GDP or output reaches a maximum and then trend begins to fall. When the economy bottoms out, a trough occurs. From this low point economic recovery sets in and eventually most sectors share in the expansion. Business Cycle Output (GDP) 0 Expansion/ Recovery peak Con t Rec rac tion essi on / Trough TIME 3 The Business cycle The Peak • THE PEAK: The peak is the point at which business activity has reached a temporary maximum • At the peak, the economy is at full employment and the level of real output is at or very close to its capacity • The price level is likely to rise during this phase RECESSION • The peak is followed by a recession—a period of decline in real output, income, employment, and trade, lasting 6 months or longer • This downturn is marked by the widespread contraction of business in many sectors of the economy • But because many prices are downwardly inflexible, the price level is likely to fall only if the recession is severe and prolonged—that is, if a depression occurs The Business Cycle (Trough) • The trough of the recession/depression is the phase in which output and employment “bottom out” at their lowest levels • The trough phase of the cycle may be short-lived or quite long The Business Cycle (RECOVERY) • In the expansion or recovery phase, output and employment increase toward full employment. • As recovery intensifies, the price level may begin to rise before there is full employment and full-capacity production Business Cycle Theories • Although economists generally agree that business cycles exist, they have many competing theories on their causes. • We will briefly consider two types of theories: – Endogenous (internal) – Exogenous (external) 8 Endogenous Theories • These theories place the cause of business cycles within rather than outside the economy. 1. Innovation Theory: when a business attempts to market a new product it will first encounter resistance. But when others perceive the profits being made by the innovator, they will imitate his new product with their own versions and production will soar. Eventually the market will be saturated and economic downturn will occur. The downturn continues until a new innovation takes hold and the process begins anew. 9 2.Psychological Theory: alternating optimism and pessimism (self-fulfilling prophecy) affects the level of economic activities. If business owners are optimistic, they will invest in plant, equipment and inventory. This will provide more jobs and result in more consumer spending, justifying still more investment, more jobs and more spending. But eventually business owners will turn pessimistic, perhaps because they figure this prosperity cannot continue. As pessimism sets in, investment, jobs, and consumer spending all decline and a recession begins. 10 3.Inventory Cycle Theory: during economic recovery, as sales begin to rise, business owners are caught short of inventory, so they raise their orders to factories, thus raising factory employment. As factory workers are called back to work, they begin to spend more money, causing business owners to order still more from factories. Eventually the owners are able to restock their inventories, so they cut back on factory orders. This causes layoffs, declining retail sales, further cutback in factory orders, and general economic decline. The decline persists until inventory levels are depleted low enough for factory orders to increase once again. 11 5. Monetary Theory: when inflation threatens, the monetary authorities slow or stop the growth of the money supply. This causes a recession. When they are satisfied that inflation is no longer a problem, the monetary authorities allow the money supply to grow at a faster rate, which brings about economic recovery. 6. Under Consumption Theory: the under consumption or over production theory stipulates that our economy periodically produces more goods and services than people want or can afford. A variant is the overinvestment in which businesses periodically overinvest in plant and equipment. 12 Exogenous Theories 1. The Sunspot Theory: William Stanley Jevon believed that storms on the sun, which were observed through telescope as sunspots, caused periodic crop failures. Bad harvest leads to recessions. 2.The War Theory: production surge caused by preparation for war and war itself cause prosperity and the letdown after war causes a recession. 13 INFLATION DEFINTION, CAUSES, MEASUREMENT, EFFECTS AND CONTROL Definition of Inflation • Inflation may be defined as a sustained rise in the average or the general price level of goods and services over a period of time. • Inflation rate is the rate at which the price level increases True or False? • Inflation means that the prices of all goods and services in the economy prices are rising • This statement is false. Inflation does not mean that the price level of all goods and services is rising. In inflation, we consider the general price level. That is, we consider on average the increase in the price level in an economy. The price level of some commodities may be rising. It may even happen that the price level of some commodities may be constant or falling slightly. We however, do not consider individually what is happening to prices of goods and services but collectively what is happening to prices of goods and services. True or False • If inflation rate is 11%, it means that the price level of all goods and services in the economy rose by 11% • This statement is False. Inflation only tells us averagely what is happening to prices. Some price may rise by 10%, others by 20%, or still others by 50% and others by 1% or even 0%. The 11% gives on average what is happening to increase in prices of all goods and services in an economy. True or False • Between January and April, inflation rate reduced from 11.5% to 10%. This means that generally the prices of goods and services are falling. • This statement is false. Anytime we speak of inflation, we never refer to decreases in prices. Deflation rather refers to decreases in price in average level of prices. However, when the rate of inflation decreases, it only tells us the rate of increase in price level is slowing. In the language of Mathematics, we say the price level generally is increasing at a decreasing rate. Types of Inflation • 1.Types by causes Demand-pull and Cost-push • 2.Types by rates of price increase Creeping Galloping/Hyperinflation • 3.Types by expectations Anticipated Unanticipated inflation Forms of Inflation Suppressed Inflation • This occurs when the government uses tough controls on price and wage levels to prevent the price from rising without eliminating the underlying inflationary pressures. • This practice often leads to quantity shortages, queues, waiting lists, and black-markets. If the system of control breaks down, as was the case in former Soviet Union, massive pent–up demand combined with significant collapse of production pulls up price level to give rise to hyperinflation. 20 Creeping Inflation • A relatively low rate of inflation such as a rate of less than 4%. The price level gradually creeps upwards. Hyperinflation • It is a type of inflation where the rate of inflation accelerates to several hundred percent a day. A classic example took place in Germany after World War I. In Germany the prices rose 10% per hour. The German government had to print larger and larger denominations of its currency. A modern day example will be that of Zimbabwe with inflation rate of more than 2 million percent (as at October 2008). Hyperinflation is associated with political crises when weak a government loses control over the economy and tends to printing money to pay its debts. 21 Stagflation • This refers to the incidence of accelerating and relatively high rates of unemployment combined with high inflation 22 Causes: Theories of inflation • Economists distinguish between two types of inflation: demand-pull inflation and cost-push inflation • 1. Demand-pull inflation. Traditionally, changes in the price level are attributed to an excess of total spending beyond the economy’s capacity to produce. • Because resources are fully employed, the business sector cannot respond to this excess demand by expanding output, so the excess demand bids up the prices of the limited real output , causing demand-pull inflation • The essence of this type of inflation is “too much spending chasing too few goods.” 1.Demand-Pull Inflation • Under demand-pull inflation, aggregate demand in the economy increases by more than aggregate supply. • In other words, the economy usually demand more goods and services than companies are able to produce. • Increased AD can come from increase in money supply, increase in population growth, economic growth, government expenditure and credit creation Causes of inflation 2. Cost-push or supply-side inflation • Inflation may also arise on the supply or cost side of the market • The theory of cost-push inflation explains rising prices in terms of factors which raise per unit production costs. • Rising per unit costs squeeze profits and reduce the amount of output firms are willing to supply at the existing price level • As a result, the economy’s supply of goods and services declines. This decline in supply drives up the price level • Under this scenario, costs are pushing the price level upward, rather than demand pulling it upwards, as with demand pull inflation • Two potential sources of cost-push inflation are increases in nominal wages and increases in the prices of nonwage inputs such as raw materials and energy • There are three variants of cost- push inflation, namely: • The Wage–price Spiral: Because wages constitutes nearly 2/3 of the cost of doing business, when ever workers receive significant wage increase, this increase is passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices. Higher prices raise everyone’s cost of living, engendering further wage increases. • The second variant of cost-push is profit-push inflation . Because just a few handful of huge firms dominate many industries (e.g. Detergents, cars, and oil), these firms have the power to administer prices in those industries rather than accept the dictates of the market forces of demand and supply. To the degree that they are able to protect their profit margins by raising prices, these firms will respond to any rise in cost by passing them on to customers. • Finally, we have the supply-side cost shock , most prominently the oil shocks of 1973-74 and 1979. When the OPEC nations quadrupled the price of oil in 1973, they touched of not just a major recession but also a severe inflation. When the price of oil increases, the cost of business rises as well and is translated into prices. 26 Measurement of Inflation • Inflation is measured by price-index numbers such as: • Consumer Price Index; Producer Price Index; and GDP deflator • A price index measures the general level of prices in any year relative to prices in a base period • The rate of inflation can be calculated for any specific year (say, 2021) by subtracting the previous year’s (2020) price index from that year’s (2021) index, dividing by the previous year’s index, and multiplying by 100 to express the result as a percentage Rule of 70 • The Consumer Price Index (CPI) • The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures changes over time in the general price level of goods and services that households acquire for the purpose of consumption, with reference to the price level in the base year, which has an index of 100. Market Basket of Ghana Inflation Basket (Food and non-food items) • Education, Hotels, Cafes and Restaurants, Health, Food and Non-alcoholic Beverages, Housing, Water, Electricity, Gas and Others Fuels , Communications, Alcoholic Beverages, Tobacco and Narcotics Furnishings, Household Equipment and Routine Maintenance, Miscellaneous Goods and Services Recreation and Culture, Clothing and Footwear, Transport Food and non-alcoholic beverages • Milk, cheese and eggs, (Sugar, jam, honey, chocolate and confectionery), Fish and sea food, Oils and fats, Cereals and cereal products, Food products n.e.c, Vegetables, Mineral water, soft drinks, fruit and vegetable juices, Meat and meat products Fruits Coffee, tea and cocoa Ways of Computing Inflation • COMPUTATION OF INFLATION • There are two basic ways of computing inflation based on the prices/cost of “market basket of goods and services” purchased by a typical consumer or producer. These are consumer price index and the producer price index. The GDP deflator could also be used to compute inflation. • Consumer Price Index • The Consumer Price Index expresses the change in the current prices of the market basket in terms of the prices during the same period in the previous year. The consumer price index is an estimation of price changes in a basket of goods and services representative of consumption expenditure in an economy. Measurement of Inflation • The CPI is usually computed monthly or quarterly. It is based on the expenditure pattern of almost all urban residents and includes people of all ages. Various categories and sub-categories have been made for classifying consumption items and on the basis of consumer categories like urban or rural. Based on these indices and sub indices obtained, the final overall index of price is calculated . Measurement of inflation • In Ghana, 2012 is used as the base year as the basis for comparison. Initially, the base year was 2002. The Ghana statistical service sets the base period CPI at 100. An index of 110 means that there’s been a 10% rise in the price of the market basket compared to the reference period. Similarly, an index of 90 indicates a 10% decrease in the price of the market basket compared to the reference period. Measurement of Inflation • An illustrative example Suppose that in a given economy, the prices of various goods and services between two periods are as follows: If 2012 is the base year, compute the rate of inflation in 2013. An illustrative example Items Price in 2012 Price in 2013 Quantity purchased (both years) Food Health Services Communication Furniture Utility (Water) 5 30 2 500 10 5.3 35 2.1 550 12 2,000 3,000 100,000 10,000 200,000 Education Fruit Juice 1300 1 1350 2 12,000 5000 Formula for computing Inflation • Cost of market basket Market value in 2013 Market value in 2012 2,000=10600 3,000=105000 100,000=210,000 10,000=5500,000 200,000=2,400,000 2,000=10000 3,000=90,000 100,000=200000 10,000=5000,000 200,000=2,000,000 12,000=16,200,000 5000=10,000 12,000=15,600,000 5000=5000 Computing Inflation • Effects of inflation A.Redistributive effect • 1.Inflation penalizes people who receive fixed nominal incomes. • Inflation redistributes real income away from fixedincome receivers and toward others in the economy • Nominal income is the number of dollars received as wages, rent, interest, or profits. Real income measures the amount of goods and services nominal income can buy • If your nominal income increases faster than the price level, your real income will rise. If the price level increases faster than your nominal income, your real income will decline • Percentage change in real income= percentage change in nominal income- percentage change in price level • Example: Landlords who receive lease payments of fixed cedi amounts will be hurt by inflation as they receive cedis in declining value over time Redistributive effect of inflation • 2.Inflation hurts savers. As price rise, the real value, or purchasing power ; of a nest egg of savings deteriorates. • Savings accounts, insurance policies, annuities, and other fixed-value paper assets once adequate to meet rainy-day contingencies or provide for a comfortable retirement decline in real value during inflation • Example: A household may save GH1000 in a certificate of deposit (CD) in a commercial bank at 6% annual in interest. But if inflation is 13%, the real value of purchasing of that GH1,000 will be cut to about (GH938) by the end of the year • The saver will receive GH 1060 (=GH 1000+ GH60 of interest), but deflating that (GH 1060 for 13% inflation means that the real value is only about GH938 (=GH1060/1.13) Redistributive effect of inflation • 3. Inflation redistributes real income between debtors and creditors • Unanticipated inflation benefits debtors (borrowers) at the expense of creditors (lenders). Unanticipated inflation is inflation whose full extent was not expected • As prices go up, the value of the cedi comes down. Thus the borrower is loaned “dear cedis” but, because of inflation pays back “cheap cedis” • At the national level, inflation reduces the real burden of public debt • In fact, some nations such as Brazil once used inflation so extensively to reduce the real value of their debt that lenders forced them to borrow money in U.S dollars or in some relatively stable currency instead of their own currency • In this way, they were prevented from using domestic inflation as a means of subtly “defaulting ‘’ on their debt because domestic inflation will only reduce the value of their currency rather than reducing the value of the dollar-denominated debt they must pay back Redistributive effect of anticipated inflation • The redistributive effects of inflation are less severe or are eliminated if people (1) anticipate inflation and (2) can adjust their nominal incomes to reflect expected price-level changes • Labour contracts with cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) agreements automatically raise worker’s nominal incomes when inflation occurs • Similarly, the redistribution of income from lender to borrower might be altered if inflation is anticipated • Lenders can avoid the erosion of the purchasing power of their money by charging an inflation premium Redistributive effect of anticipated inflation • The inflation premium is the expected rate of inflation • This could be done by increasing the interest rate by the rate of anticipated inflation • In this case, the real rate of interest—which is the percentage increase in purchasing power—which the lender receives from the borrower is the difference between the money/nominal rate of interest and the rate of inflation • Nominal interest rate=real interest rate + inflation premium B. Output effects of inflation • 1.Stimulus of demand-pull inflation. Some economists argue that full-employment can be achieved only if some modest amount of inflation is tolerated • These economists argue that if spending is low, the economy will have price stability, but real output will be substantially below its potential and the unemployment rate is high • If total spending increases, society must accept a higher price level—some amount if inflation—to achieve greater real output and the accompanying lower unemployment rates Output effects of inflation • Cost-push inflation and unemployment. There is an equally plausible set of circumstances in which inflation might reduce both output and employment • If the economy starts from a point where the level of total spending helps achieves full employment and price level stability, and cost-push inflation occurs, then the level of total spending cannot buy the existing real output due to high prices. • This will lead to a fall in real output and unemployment Hyperinflation and Breakdown • Some economists are fearful that the mild, “creeping” inflation which might initially accompany an economic recovery phase can snowball into severe hyperinflation • Hyperinflation is an extremely rapid inflation whose impact on real output and employment can be devastating • As prices persist in creeping upward, households and businesses will expect them to rise further. So rather than let their idle savings and current incomes depreciate, people will “spend now” to beat unanticipated price rises. • Businesses will do the same by buying capital goods • Actions based on this “inflationary psychosis” will then intensify the pressure on prices, and inflation will feed on itself Hyperinflation (Wage-price inflationary spiral) • Furthermore, as price rises, labour will demand and get higher nominal wages. Unions may seek increases sufficient not only to cover last year’s price increases but also compensate for inflation anticipated during the future life of their new collective bargaining agreements. • Firms will not resist such demands, but will jack up prices of their goods to recoup the rising labour costs • Increases in price of goods will make workers further demand high wages, triggering another round of price increases from firms , and then to workers, and so on. • The net effect is a cumulative wage-price inflationary spiral • Nominal wage and price rises feed on each other and transform creeping inflation into galloping inflation • • • • • Hyperinflation and economic collapse Aside from its disruptive redistribution effects, hyperinflation can cause economic collapse Severe inflation encourages speculative activity Businesses may find it increasingly profitable to hoard both materials and finished products, anticipating further price increases But restricting the availability of materials and products intensifies the inflationary pressure Also, rather than invest in capital equipment, businesses and individuals savers may purchase unproductive wealth—jewels, gold and other precious metals, real estate, and so forth—as a hedge against inflation Hyperinflation and economic collapse • In the extreme, with high prices, normal economic activities are disrupted: businesses do not know what to charge for their products; consumers do not know what to pay; resources suppliers want to be paid with actual output rather than money; creditors avoid debtors • Eventually , MONEY BECOMES WORTHLESS, the economy enters into a barter, production and exchange drop dramatically • Consequently, economic, social and a possible political catastrophe emerges Historical examples of hyperinflation 1.The case of Hungary • “The inflation in Hungary exceeded all known records of the past. In August 1946, 828 octillion (1 followed by 27 zeros) depreciated pengos equaled the value of 1 prewar pengo. The price of the American dollar reached a value of 3*10*22 (3 followed by 22 zeros) pengos. Fishermen and farmers in 1947 Japan used scales to weigh currency and change, rather than bothering to count it. Prices rose by some 116 imes in Japan, 1938 to 1948” (Morgan, 1952) Historical examples of hyperinflation 2. The case of Germany • Faced with huge budget deficits, the Weimar government simply ran the printing press to meet the bills. During 1922, the German price level went up 5, 470 percent. In 1923,the situation worsened; the German price rose 1,300,000,000,000 times. By October of 1923, the postage of lightest letter sent from Germany to US was 200,000 marks. Butter cost 1.5 million marks per pound, meat 2million marks and an egg 600,000 marks • Prices increased so rapidly that sometimes waiters changed the menu several times during the course of a lunch. Sometimes customers had to pay double prices listed on the menu when they ordered” (Williams,1980) Control of Inflation • Demand-Pull • Use of Monetary Policies – Monetary Policy involves the use of money supply and interest rates to control the level of economic activities in an economy. The government through the central bank could use certain policies such OMO, bank rates, etc to control inflation. In this case credit squeeze policies are used to help reduce money supply in the economy. With the reduction in money supply, demand for goods and services may also reduce to bring down increases in the general price level. • Use of Fiscal Policies – Fiscal policy involves the use of government spending and taxes to regulate economic activities. The government can also use fiscal policies such as taxation to reduce the disposal income of people. Government should not spend on ambitious and unproductive ventures, project or infrastructure through borrowing from the financial institutions. Government financing of project through printing of new notes increases the money supply that tends to fuel the level of inflation. 54 • Supply-Push • Reasonable wage increases – higher wage demands increase cost of production which leads to higher prices. Wage increases should be accompanied by equal higher productivity. Government should control the activities of trade unions • Increase production – increasing production of goods to prevent shortages can and most importantly control inflation. The problems of the agricultural sector that tend to increase cost of food should be solved. • Grant subsidies to increase production 55 UNEMPLOYMENT DEFINITION, TYPES, CUASES, AND CONTROL Definition of Unemployment • The International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) of the ILO considers a person of working age (e. g. 15+years in Ghana) to be unemployed if during a specified reference period (either a day or a week), that person had been: • ‘without work’, not even for one hour in paid employment or self‐employment of the type covered by the international definition of employment; • ‘currently available for work’, whether for paid employment or self‐employment; and • ‘seeking work’, by taking active steps in a specified recent period to seek paid employment or self‐employment Measurement of Unemployment • Determining the unemployment rate means first determining who is eligible and available to work • We can divide the total population into three groups: those who are under 16 and/or institutionalized; those who are “not in the labour force”; and those who are employed • Those who are under 16 and/or institutionalized, for example, in mental hospitals or correctional institutions. These people are not considered potential members of the labour force Measurement of Unemployment • Those who are “not in the labour force” are adults who are potential workers but for some reason—they are homemakers, in school, or retired—are not employed and are not seeking work • The labour force is all people who are able and willing to work. Both those who are employed and those who are unemployed but actively seeking work are counted as being in the labour force Measuring unemployment: The U. S Approach • Unemployment rate in U.S comes from a survey of 60000 households who respond to survey questions. Only adults (16+). Each household is put into each of the following categories: • Employed: These include those who responded to the survey that they worked as paid employees, worked in their own business or worked as unpaid workers in a family business. Those who were temporary absent due to vacation, illness or bad weather are also included. • Unemployed: Those unemployed but were available for work and had tried to find employment during the previous four weeks, those waiting to be recalled to a job from which they had been laid off • Not in the labour force: full time students, homemakers or retirees Measuring Unemployment • Flows Into and Out of Unemployment 62 Discouraged worker and moonlighting • Some on who is available for work but who fails to exert the required effort in seeking work is known as discouraged worker • If an individual who is gainfully employed searches for additional job to boost his earnings or diversify his work portfolio, then we say that person is moonlighting. Types of Unemployment • The major types of unemployment are voluntary and involuntary unemployment • (1) Voluntary unemployment consists of: • (a) Frictional Unemployment • (b) Structural unemployment • (2) Involuntary Unemployment consists of: • (a) Cyclical unemployment • (b) Seasonal Unemployment Involuntary Unemployment • Involuntary unemployment is said to exist if individuals cannot obtain work even if they are prepared to accept lower real wages or poorer conditions than similar qualified workers who are currently in employment (Shackleton, 1985). Causes of involuntary unemployment • 1.Institutional factors • Some government regulations such as fixing minimum wages can distort the efficiency of the market system in providing jobs. When the market system is allowed to work such that in the labour market, wages are determined by the point where demand for labour is equal to the supply of labour, then the market will ensure that everybody gets a job. Causes of involuntary unemployment • 1.Institutional factors • But if government, perhaps, realizing that the market wage is low decides to fix a wage rate above the market level, then employers will respond by cutting down their demand for labour in order to be able to meet the legally enforced wage rate imposed by the government. But while demand for labour will reduce, more people will join the labour market because now they see it is worth ’working’ since they believe that they will be paid well. The excess labour creates unemployment. Causes of Involuntary Unemployment • 2. Efficient wage Hypothesis • According to this theory, unemployment results when firm fix efficient wages. Firms set efficient wages for several reasons: • A. To ensure workers do not shirk • B. To reduce high turnover which will eventually increase cost of production • C. To attract highly qualified workers • D. To induce a gift mentality in workers • As a result of the high wages, only ‘few hands’ are needed and job seekers are turned away CAUSES OF INVOLUNTARY UNEMPLOYMENT • 3. INSIDER-OUTSIDER HYPOTHESIS • According to another economic model known as the insider-outsider model, unemployment results from the action of institutional players such as the trade union who takes decision to fix wages taking into consideration only the interest of those who are employed. They set laws to ensure that even those outsiders who want to work at lower wages cannot do so. • Also to reduce high turnover, firms pay good wages to the insiders (employees). As a result, the interest of the outsiders (job seekers ) are ignored Causes of Involuntary unemployment • 4.FALL IN AGGREGATE DEMAND • Unemployment can also result from a situation where there is a lower aggregate demand to meet output. In other words, in the entire economy, demand for goods and services are low. Demand for goods and services come from consumers (household expenditure), investment (purchases of businesses), government and net export. • When, for example, consumers are not buying what is produced in the economy, inventory (stock of unsold goods in the warehouse) builds up and firm cuts on production and reduce the demand for labour. This is also known as cyclical unemployment . Here, there is deficiency in the demand for goods and services. • Cyclical Unemployment: Because of the general decline in the demand for products during a recession most firms reduce their demand for all inputs including labor. • This type of unemployment is consistent with the ups and downs of the business cycle and reflects the decline in aggregate output that occurs during the recessionary phase of the business cycle. It is thus defined as the extra unemployment that occurs during periods of recession. 71 Involuntary unemployment: Seasonal Unemployment • Another variant of involuntary unemployment isseasonal unemployment . • In this type of unemployment, seasonal variations in demand cause insufficient demand and hence reducing the demand for labour. VOLUNTARY UNEMPLOYMENT: CAUSES • 1. FRICTIONAL UNEMPLOYMENT • Economists use the term frictional unemployment—consisting of search unemployment and wait unemployment—for workers who are either searching for jobs or waiting to take jobs in the near future • At any time some workers will be “between jobs”. With freedom to choose occupations and jobs, some workers will be voluntarily moving from one job to another • Others will have been fired and will be seeking reemployment. Others will be temporarily laid off from their jobs because of seasonality, for example bad weather. • There will be some particularly young workers searching for their first time jobs • As these unemployed people find jobs or are called back from temporary layoffs, other job seekers and temporarily laid-off workers will replace them in the “unemployment pool” Frictional Unemployment • “Frictional “ correctly implies that the labour market does not operate perfectly or instantaneously—without friction—in matching workers and jobs. • Many workers who are voluntarily between jobs, are moving from lowpaying , low productivity positions. • This means greater income for workers and a better allocation of labour resources—and therefore a larger real output—for the economy as a whole. CAUSES OF VOLUNTARY UNEMPLOYMENT • 2.STRUCTURAL UNEMPLOYMENT • Another form of voluntary unemployment is structural unemployment . This happens when there is a mismatch between the skills required at the work place and that possesses by the worker. • Changes over time in consumer demand and in technology alter the “structure” of the total demand for labour, both occupationally and geographically • Occupationally, some skills will be in less demand or may even become obsolete; demand for other skills, including skills not existing earlier, will expand Structural Unemployment • Structural Unemployment results because the composition of the labour force does not respond quickly or completely to the new structure of job opportunities • Some workers thus find that they have no marketable talents; their skills and experiences have become obsolete or unneeded • They are structurally unemployed due to a mismatch between their skills and the skills required by employers who are hiring workers. Causes of Voluntary Unemployment • 2.STRUCTURAL UNEMPLOYMENT • Geographically, the demand for labour also changes over time. Industries can migrate from one region to another. • These shift in job opportunities mean that some workers become structurally unemployed; there is a mismatch between their location and the location of the job openings • The Natural Rate of The economy’sUnemployment natural rate of unemployment refers to the amount of unemployment that the economy normally experiences at full employment. It can also be defined as the level of unemployment in an economy when the labour market is in long-run equilibrium, that is, when the total demand for labour is equal to the supply of labour at the prevailing level of real wage rate. • In this situation, people may be unemployed because: a) they are between jobs and are taking time to search for the most appropriate job with the highest wage (frictional unemployment). b) the industry in which they have traditionally worked has experienced a structural decline or has been influenced by technological advances (structural/technological unemployment) c) There has been a seasonal decline in the demand for their labour services (seasonal unemployment). 78 Natural rate of unemployment/ “Full Employment” • Full employment does not mean zero unemployment. Economists regard frictional and structural unemployment as essentially unavoidable in a dynamic economy • Thus “full employment” is something less than 100 percent employment of the labour force • Specifically, the full employment rate is equal to the total frictional and structural unemployment • State differently, the full-employment unemployment rate is achieved when cyclical unemployment is zero “Full Employment” • The full-employment rate of unemployment is also referred to as the natural rate of unemployment • The real level of domestic output associated with the natural rate of unemployment is called the economy’s potential output • The economy’s potential output is the real output produced when the economy is “fully employed.” Effects of Unemployment • Economic Cost: Okun’s law • The basic economic cost of unemployment is forgone output. When the economy fails to create enough jobs for all who are able and willing to work, potential production of goods and services is irretrievably lost • Economists measure this sacrificed output as the GDP gap—the amount by which actual GDP falls short of potential GDP • Potential GDP is determined by assuming that the natural rate of unemployment exists • Macroeconomists Arthur Okun quantified the relationship between the unemployment rate and the GDP gap. Okun’s law, based on recent estimates, indicates that for every 1 percentage point which the actual unemployment rate exceeds the natural rate, a GDP gap of about 2 percent occurs Other economic costs • It leads to loss of revenue for the government as these people will not be able to pay tax. • Consequently, an economy with high unemployment will be running budget deficit and resort to borrowing leading to high public debt. Effects of Unemployment • Noneconomic Cost • Severe cyclical unemployment is more than an economic malady; it is a social catastrophe • Depression means idleness. And idleness means loss of skills, loss of self-respect, a plummeting of morale, family disintegration, and sociopolitical unrest. • A job “… gives hope for material and social advancement. It is a way of providing one’s children a better start in life. It may mean the only honourable way of escape from the poverty of one’s parents. It helps to overcome racial and other social barriers. In short… a job is the passport to freedom and to a better life. To deprive people of jobs is to read them out of our society “ (Reuss, 1964, p.133) Effects of unemployment Noneconomic cost • It leads to poor health and lower attainment of education e.g child labour • It has psychological effect on jobseekers and further worsen health • It can create disaffection among jobseekers and some of them, especially the youth, can resort to social vices such as robbery, prostitution • It leads to social upheavals and political unrest. • It breeds poverty and deprivations