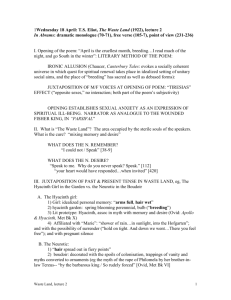

2 Section A: Prose Answer one question from this section. IAN MCEWAN: Atonement Question 1 (b) Comment closely on ways in which McEwan makes this an impactful moment in the novel. [25] “He’s suffering too much. I don’t want him treated until I get him hydrated. Go and find something else to do.” Briony did as she was told. She did not know how much later it was—perhaps it was in the small hours when she was sent to get fresh towels. She saw the nurse standing near the entrance to the duty room, unobtrusively crying. Corporal MacIntyre was dead. His 5 bed was already taken by another case. The probationers and the second-year students worked twelve hours without rest. The other trainees and the qualified nurses worked on, and no one could remember how long they were in the wards. All the training she had received, Briony felt later, had been useful preparation, especially in obedience, but everything she understood about nursing 10 she learned that night. She had never seen men crying before. It shocked her at first, and within the hour she was used to it. On the other hand, the stoicism of some of the soldiers amazed and even appalled her. Men coming round from amputations seemed compelled to make terrible jokes. What am I going to kick the missus with now? Every secret of the body was rendered up—bone risen through flesh, sacrilegious glimpses of an 15 intestine or an optic nerve. From this new and intimate perspective, she learned a simple, obvious thing she had always known, and everyone knew: that a person is, among all else, a material thing, easily torn, not easily mended. She came the closest she would ever be to the battlefield, for every case she helped with had some of its essential elements—blood, oil, sand, mud, seawater, bullets, shrapnel, engine grease, or the smell 20 of cordite, or damp sweaty battle dress whose pockets contained rancid food along with the sodden crumbs of Amo bars. Often, when she returned yet again to the sink with the high taps and the soda block, it was beach sand she scrubbed away from between her fingers. She and the other probationers of her set were aware of each other only as nurses, not as friends: she barely registered that one of the girls who had helped to move 25 Corporal MacIntyre onto the bedpan was Fiona. Sometimes, when a soldier Briony was looking after was in great pain, she was touched by an impersonal tenderness that detached her from the suffering, so that she was able to do her work efficiently and without horror. That was when she saw what nursing might be, and she longed to qualify, to have that badge. She could imagine how she might abandon her ambitions of writing 30 and dedicate her life in return for these moments of elated, generalized love. Toward three-thirty in the morning, she was told to go and see Sister Drummond. She was on her own, making up a bed. Earlier, Briony had seen her in the sluice room. She seemed to be everywhere, doing jobs at every level. Automatically, Briony began to help her. The sister said, “I seem to remember that you speak a bit of French.” 35 9695/22/AUG21/ASTRIAL 3 “It’s only school French, Sister.” She nodded toward the end of the ward. “You see that soldier sitting up, at the end of the row? Acute surgical, but there’s no need to wear a mask. Find a chair, go and sit with him. Hold his hand and talk to him.” Briony could not help feeling offended. “But I’m not tired, Sister. Honestly, I’m not.” “You’ll do as you’re told.” “Yes, Sister.” He looked like a boy of fifteen, but she saw from his chart that he was her own age, eighteen. He was sitting, propped by several pillows, watching the commotion around him with a kind of abstracted childlike wonder. It was hard to think of him as a soldier. He had a fine, delicate face, with dark eyebrows and dark green eyes, and a soft full mouth. His face was white and had an unusual sheen, and the eyes were unhealthily radiant. His head was heavily bandaged. As she brought up her chair and sat down he smiled as though he had been expecting her, and when she took his hand he did not seem surprised. “Te voilà enfin.” The French vowels had a musical twang, but she could just about understand him. His hand was cold and greasy to the touch. She said, “The sister told me to come and have a little chat with you.” Not knowing the word, she translated “sister” literally. “Your sister is very kind.” Then he cocked his head and added, “But she always was. And is all going well for her? What does she do these days?” There was such friendliness and charm in his eyes, such boyish eagerness to engage her, that she could only go along. “She’s a nurse too.” “Of course. You told me before. Is she still happy?” 9695/22/AUG21/ASTRIAL 40 45 50 55 60 4 Section B: Unseen Answer one question from this section. EITHER Question 2 Comment closely on the following passage, considering its presentation of the Hyacinth’s situation, a girl from Jamaica, has been sent to join her father, living in London. In your answer, consider choice of language, dialogue and narrative methods. The three of them were in their secret place again and the sound of their laughter rose through the sweet-scented bushes from where they lay. Hyacinth felt the lazy warmth of the early afternoon air wrap her in well-being as she lay back in the cool grass, listening idly to the conversation. It was safe in this little green cave, the recesses of the bushes laden with long-stemmed hibiscus and yellow trumpet flowers and humming with insect activity. They were talking about the Independence parade just past, and Hyacinth soon lost interest, her mind centred on the warm glow of contentment somewhere in the centre of her chest. She was slipping back, back to the fever of anticipation, the mounting impatience as the minutes on the face of the monument clock slipped slowly by. Hyacinth was hopping from foot to foot, caught in the excitement, part of that jostling good-natured crowd, craning forward, impatient to see the first float appear. They had been lucky to get a place right at the front, and she pressed closer to Aunt Joyce’s reassuring bulk as the crowd surged against her. She was glad of the canecutter’s hat on her head, and of the little breeze that was so cool where it blew on the wet patches of sweat on her back and under her arms. Aunt Joyce had a big sombrero slung lazily across her bulk, eyes squinting against the glare of the sun, the usual smile on her face as she turned every few minutes to exchange words with her neighbour. 9695/22/AUG21/ASTRIAL [25] 5 10 15 5 Suddenly there was silence in the crowd. Far away in the distance came the sound of a flute, followed by the boom of a big goatskin drum. Hyacinth’s heart skipped a beat, then raced with excitement. She shuffled, as the crowd surged around her, craning forward, pushing out eagerly, wanting to catch her first glimpse of the colourful band float. Her aunt’s big hand grabbed her dress, shook her. ‘Hyacinth! Hyacinth!’ She shrugged impatiently, trying to shake free of the hand, caught in the excitement of the day. But it gripped on, refused to be dislodged. ‘Hyacinth!’ The voice had become insistent, the hand moved to her shoulder, curled round, became biting, vicious, a painful pinch that seemed to pull her back. ‘Hyacinth, wake up!’ The voice was no longer the mellow one of her good-natured aunt. Harsh and strident, the accent grated on her ears, as a final vicious shake yanked her away from her peace. Coldness enveloped her, clammy cold fingers dragged her back to consciousness. Her mind struggled in confusion, unable to grasp the change for a few, endless seconds. ‘You wet the bed again!’ The words came out on a snap of teeth, a hiss of anger, bringing painful and instant awareness with them. Hyacinth struggled to sit up, eyes opening reluctantly to dingy grey walls, before moving blankly to the equally grey sky she could just glimpse through the ill-fitting curtains. ‘Look at me, girl!’ Dull eyes slid sullenly across the mean room, locking apprehensively with protruding bloodshot spite as the yellow-skinned woman glared her hatred down at her. Hyacinth forced herself to stay calm, not to beg. Her mind still wrestling with the shock of disappointment, she clenched herself against the cold that stung and bit, where the sodden nightdress clung to her in clammy folds. She would have clutched herself for warmth, but knew that the woman would see it as defiance. Instead she hung her head, hands loose beside her on the sheet, becoming gradually aware of feeling slightly breathless, of a pulse drumming in her ears, and her eyes burning with self-pity and the desire to cry. ‘Get up, girl,’ the woman shouted, as Hyacinth continued to sit in silent misery. She stayed where she was, incapable of response, of obedience, for a few moments. The woman shifted menacingly, and Hyacinth could sense the angry impatience within her. It mobilised her, caused her to push her legs to the floor in an automatic motion. Her whole body was mechanical, twisting jerkily, legs shifting, feet lowered to cold floorboards, dragging her sodden cotton nightdress as she stood. Thin, rank cloth clung to her and the angle of her body was tense and awkward with expectation. ‘Wait till your father gets home!’ It was said with triumph, a final blow against an already defeated enemy. 9695/22/AUG21/ASTRIAL 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 6 OR [Turn over Question 3 Discuss the presentation of rain in the following poem. Consider the writer’s choice of language, imagery and structure in your answer. [25] Night Rain What time of night it is I do not know Except that like some fish Doped out of the deep I have bobbed up bellywise From stream of sleep And no cocks crow. It is drumming hard here And I suppose everywhere Droning with insistent ardour upon Our roof-thatch and shed And through sheaves slit open To lighting and rafters I cannot make out overhead Great water drops are dribbling Falling like orange or mango Fruits showered forth in the wind Or perhaps I should say so Much like beads I could in prayer tell Them on string as they break In wooden bowls and earthenware Mother is busy now deploying About our roomlet and floor. 9695/22/AUG21/ASTRIAL 5 10 15 20 7 Although it is so dark I know her practised step as She moves her bins, bags, and vats Out of the run of water That like ants filing out of the wood Will scatter and gain possession Of the floor. Do not tremble then But turn brothers, turn upon your side Of the loosening mats To where the others lie. We have drunk tonight of a spell Deeper than the owl’s or bat’s That wet of wings may not fly. Bedraggled upon the iroko1, they stand Emptied of hearts, and Therefore will not stir, no, not Even at dawn for then They must scurry in to hide. So we’ll roll over on our back And again roll to the beat Of drumming all over the land And under its ample soothing hand Joined to that of the sea We will settle to sleep of the innocent. 1 iroko: large African tree 9695/22/AUG21/ASTRIAL 25 30 35 40 45