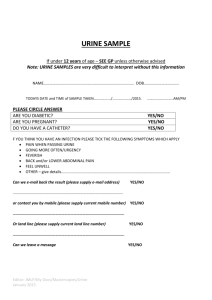

CHAP 32: KIN AND WOUND CARE- 8 SKILLS P.1093 I. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM 1. Structures of the Skin (TABLE 32.1) The skin, or integument, is the largest organ of the body and has multiple functions. The skin covers the entire body and is continuous with mucous membranes at normal body orifices. It is essential for maintaining life. The top layer, or outermost portion, is the epidermis. The epidermis is composed of layers of stratified epithelial cells. These cells fuse to form a protective, waterproof layer of keratin material. Epithelial cells have no blood vessels of their own and depend on underlying tissues for nourishment and waste removal. The second layer of skin, the dermis, consists of a framework of elastic connective tissue comprised primarily of collagen. Nerves, hair follicles, glands, immune cells, and blood vessels are located in this layer The dermis rests on the subcutaneous tissue, the underlying layer that anchors the skin layers to the underlying tissues of the body. The subcutaneous tissue consists of adipose tissue, made up of lobules of fat cells, and connective tissue. This layer stores fat for energy, serves as a heat insulator for the body, and provides a cushioning effect for protection. This fatty tissue layer contains blood and lymph vessels, nerves, and fat cells. 2. Functions of the Skin and Mucous Membranes (TABLE 32.1) The skin has multiple functions: protection, temperature regulation, psychosocial, sensation, vitamin D production, immunologic, absorption, and elimination Mucous membranes line body cavities that open to the outside of the body, joining with the skin. They can also be found in the digestive tract, the respiratory passages, and the urinary and reproductive tracts. Mucous membranes have receptors that offer the body protection. For example, an irritating substance in the upper respiratory tract causes a person to sneeze, and food caught in the larynx or trachea causes a person to cough. Sneezing and coughing are protective mechanisms that help rid the body of foreign materials. Mucous membranes are insensitive to temperature, except in the mouth and rectum, but are sensitive to pressure. For example, digested food is absorbed through the mucous membrane in the small intestine. 3. Factors Affecting Skin Integrity -Unbroken and healthy skin and mucous membranes serve as the first lines of defense against harmful agents. - Resistance to injury of the skin and mucous membranes varies among people. Factors influencing resistance include the person’s age, the amount of underlying tissues, and illness conditions. -Adequately nourished and hydrated body cells are resistant to injury. The better nourished the cell is, the better able it is to resist injury and disease. - Adequate circulation is necessary to maintain cell life. When circulation is impaired for any reason, cells receive inadequate nourishment and cannot remove wastes efficiently. 1. Developmental Considerations In children younger than 2 years, the skin is thinner and weaker than it is in adults. A child’s skin becomes increasingly resistant to injury and infection. In older adults, the maturation of epidermal cells is prolonged, leading to thin, easily damaged skin. Circulation and collagen formation are impaired, leading to decreased elasticity and increased risk for tissue damage from pressure. A. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF INTEGUMENTARY I. STRUCTURE OF THE SKIN II. Function of the kin and mucous membrane III. Factors affect skin integrity 1. Developmental Considerations 2. State of Health B. WOUND AND PRESSURE INJURY I. Wound classification (***) (table 32.3) Chu y Pressure ulcer, arterial ulcer, venous ulcer, and diabetic ulcer ( ppt and sach) II. Wound healing (***) 1. Phase of wound healing (hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and maturation) 2. Factors affecting wound healing Local factors: pressure, desiccation (hydration), maceration (overhydration), trauma, edema, infection, excessive bleeding, necrosis (death tissue), biofilm Systemic Factors: age, circulation and oxygenation, nutrition, wound etiology (cause), medication and health status, immunosuppression, adherence to treatment plan 3. Wound complication (*** Infection (risk increase in surgery of intestine cuz contact w feces, purulent drainage w other sign and symptom) Hemorrhage: o Hemorrhage may occur from a slipped suture, a dislodged clot at the wound site, infection, or the erosion of a blood vessel by a foreign body, such as a drain. o Internal hemorrhage causes the formation of a hematoma, a localized mass of usually clotted blood o If the bleeding leads to a large accumulation of blood, it can put pressure on surrounding blood vessels and cause tissue ischemia (deficiency of blood to an area). Dehiscence: Dehiscence is the partial or total separation of wound layers as a result of excessive stress on wounds that are not healed. Evisceration : o In evisceration, the abdominal wound completely separates, with protrusion of viscera (internal organs) through the incisional area. o Patients at greater risk for these complications include those who are obese or malnourished, smoke tobacco, use anticoagulants, have infected wounds, or experience excessive coughing, vomiting, or straining o An increase in the flow of (serosanguineous) fluid from the wound between postoperative days 4 and 5 may be a sign of an impending dehiscence. o o If dehiscence occurs, cover the wound area with sterile towels moistened with sterile 0.9% sodium chloride solution and notify the health care provider. Place the patient in the low Fowler’s position and cover the exposed abdominal contents, as discussed previously, being sure to keep the exposed viscera moist. Do not leave the patient alone, Fistula o o o A fistula is an abnormal passage from an internal organ or vessel to the outside of the body or from one internal organ or vessel to another. However, fistula formation is often the result of infection that has developed into an abscess, which is a collection of infected fluid that has not drained. (Accumulated fluid applies pressure to surrounding tissues, leading to the formation of the unnatural passage between two viscous organs or an organ and the skin) The presence of a fistula increases the risk for delayed healing, additional infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalances, and skin breakdown. C. PRESSURE INJURY A pressure injury is defined as localized damage to the skin and underlying tissue that usually occurs over a bony prominence or is related to the use of a (medical or other) device I. Factors in pressure injury develop 1. External Pressure 2. Friction and Shear Friction occurs when two surfaces rub against each other. A patient who lies on wrinkled sheets is likely to sustain tissue damage as a result of friction The skin over the elbows and heels often is injured due to friction when patients lift and help move themselves up in bed with the use of their arms and feet Friction burns can also occur on the back when patients are pulled or slid over sheets while being moved up in bed or transferred onto a stretcher. Shear results when one layer of tissue slides over another layer. Patients who are pulled, rather than lifted, when being moved up in bed or from bed to chair or stretcher are at risk for injury from shearing forces A patient who is partially sitting up in bed is susceptible to shearing force when the skin sticks to the sheet and underlying tissues move downward with the body toward the foot of the bed. This may also occur in a patient who sits in a chair but slides down. II. Risks for develop pressure injury 1. Immobility 2. Nutrition and hydration 3. Moisture 4. Mental tatus 5. Age III. Pressure Injury Staging: 4 stages, unstable and deep tissue (***) 1. A stage 1 pressure injury is a defined, localized area of intact skin with nonblanchable erythema (redness). The area may be painful, firm, soft, warmer, or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue 2. A stage 2 pressure injury involves partial-thickness loss of dermis and presents as a shallow, open ulcer or a ruptured/intact serum-filled blister 3. A stage 3 pressure injury presents with full-thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible and epibole (rolled wound edges) may occur, but bone, tendon, or muscle is not exposed. Slough and/or eschar that may be present do not obscure the depth of tissue loss. Ulcers at this stage may include undermining and tunneling 4. Stage 4 injuries involve full-thickness tissue loss with exposed or palpable bone, cartilage, ligament, tendon, fascia, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some part of the wound bed; epibole, undermining, and/or tunneling often occur 5. When the clinician is unable to visualize the extent of tissue damage due to slough or eschar, pressure injuries are classified as unstageable. Slough is yellow, tan, gray, green, or brown dead tissue; eschar is tan, brown, or black hardened dead tissue (necrosis) in the wound bed IV. Psychology effect of wound and pressure injury 1. Pain 2. Anxiety and Fear 3. Activities of Daily Living 4. Changes in body Image D. HEAT AND COLD THERAPY 1. Effect of applying heat The application of local heat dilates peripheral blood vessels, increases tissue metabolism, increases capillary permeability (improves the delivery of leukocytes and nutrients) reduces blood viscosity, reduces muscle tension, helps relieve pain. Heat reduces muscle tension to promote relaxation and helps to relieve muscle spasms and joint stiffness. Heat also helps relieve pain by stimulating specific nerve fibers, closing the gate that allows the transmission of pain stimuli to centers in the brain Vasodilation increases local blood flow. In turn, the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the area is increased, and venous congestion is decreased heat in various forms is used to treat infections, surgical wounds, inflamed tissue, arthritis, joint and muscle pain, dysmenorrhea, and chronic pain. The systemic effects of extensive, prolonged heat include increased cardiac output, sweating, increased pulse rate, and decreased blood pressure. 2. Effect of applying cold The local application of cold constricts peripheral blood vessels, reduces muscle spasms, and promotes comfort. Cold reduces blood flow to tissues and decreases the local release of painproducing substances such as histamine, serotonin, and bradykinin. This action in turn reduces the formation of edema and inflammation. Decreased metabolic needs and capillary permeability, combined with increased coagulation of blood at the wound site, Cold also reduces muscle spasm, alters tissue sensitivity (producing numbness), and promotes comfort by slowing the transmission of pain stimuli. Exposure to prolonged or extensive environmental cold produces systemic effects of increased blood pressure, shivering, and goose bumps. Although shivering is a normal body response to cold, prolonged cold may cause tissue injury. 3. Nursing process for heat and cold therapy a. Assessment ( overall, area, equipment) b. Diagnosis (acute pain, chronic pain, ineffective tissue perfusion, risk for injury) c. Planning d. Implementing: APPLY HEAT: 1. Dry heat Hot water bags Electric heating pad Aquathermia pads Hot packs 2. Moist heat Warm moist compresses Sitz bath Warm soaks APPLYING COLD 1. Dry cold Ice bags Cold packs 2. Moist cold Cold compresses ( eye: surgical gauze compress, head and face: wash cloth compress) E. NURSING PROCESS I. ASSESSMENT 1. Nursing Assessment: When obtaining the nursing history, include questions about the appearance of the skin and patient activities that may contribute to the development of a pressure injury. Also, assess activity status, nutritional state, elimination patterns, and cognitive state. Be alert for signs and symptoms of infection, which may cause generalized malaise, increased pain, anorexia, and an elevated body temperature and pulse rate 2. Skin assessment o Be sure to inspect the skin systematically in a head-to-toe fashion, including bony prominences, on admission and then at regular intervals for all at-risk patients o Reassessment is recommended: Acute care setting: On admission, then reassess every shift and with any change in condition Long-term care setting: On admission, then reassess weekly for 4 weeks, then quarterly and whenever the resident’s condition changes Home health care: On admission, then reassess at every visit 3. Wound assessment Inspection ( sight and smell), palpation (appearance, drainage, odor and pain) Appearance: location, size (length, width, depth, tunnel (12 o’clock, clockwise direction, document the deepest sites where the wound tunnels). Assess wounds for the approximation of the wound edges (edges meet) and signs of dehiscence or evisceration. Assess the color of the wound and surrounding area. Note the presence of drains, tubes, staples, and sutures Drainage(***)- TABLE 32.4 : TYPES OF DRAIN AND CARE Serous drainage is composed primarily of the clear, serous portion of the blood and from serous membranes. Serous drainage is clear and watery. Sanguineous drainage consists of large numbers of red blood cells and looks like blood. Brightred sanguineous drainage is indicative of fresh bleeding, whereas darker drainage indicates older bleeding. Serosanguineous drainage is a mixture of serum and red blood cells. It is light pink to blood tinged. Purulent drainage is made up of white blood cells, liquefied dead tissue debris, and both dead and live bacteria. Purulent drainage is thick, often has a musty or foul odor, and varies in color (such as dark yellow or green), depending on the causative organism. The inflammatory response results in the formation of exudate which then drains from the wound. The exudate may contain fluid/serum, cellular debris, bacteria, and leukocytes. This exudate is called wound drainage Sutures and Staples: Skin sutures are used to hold tissue and skin together. Sutures may be black silk, synthetic material, or fine wire. Sutures are removed when enough tensile strength has developed to hold the wound edges together during healing 4. Pressure Injury assessment Risk assessment Norton Scale: physical and mental conditions, activity, mobility, and incontinence Waterlow Scale: age and gender (sex), build and weight, continence, skin type, mobility, nutrition, and special population-specific risks (Waterlow, 1985) Braden Scale: mental status, continence, mobility, activity, and nutrition Using the Braden scale, a score of 19 to 23 indicates no risk; 15 to 18, mild risk; 13 to 14, moderate risk; 10 to 12, high risk; and 9 or lower, very high risk II. MOBILITY Assessing a patient’s mobility includes evaluating the patient’s ability to move, turn, and reposition the body. A patient who is confined to bed or a chair, or has limited range of motion is at increased risk for a pressure injury Nutritional status(Hydration and weight Moisture and Continence Appearance of existing pressure injury (location, size, stage) Presence of any abnormal pathways in the wound, such as a sinus tract (a cavity or channel underneath the wound that has the potential for infection) or tunneling (a passageway or opening that may be visible at skin level, but with most of the tunnel under the surface of the skin). 5. Pain assessment Focus assessment on whether dressing changes, positioning in bed or in a chair, or movement elicits any expressions of pain. DIAGNOSING Disturbed Body Image Deficient Knowledge related to wound care Impaired Tissue Integrity Impaired Skin Integrity Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity Risk for Infection III. PLANNING IV. IMPLEMENTING 1. Preventing pressure injuries (***)- Guideline 32.2 Tissue load management refers to therapeutic means to manage pressure, friction, and shear on tissues To protect patients at risk from the adverse effects of pressure, implement turning and positioning schedules, as well as the use of appropriate support surfaces (tissue load management surfaces) Turning bed-bound patients every two hours and repositioning chair-bound patients every hour The oblique position, an alternative to the side-lying position, results in significantly less pressure on the trochanter area. Do not position the head of the bed above 30 degrees unless medically contraindicated, and alternate right side, back, left side, and prone positions (when tolerated) using appropriate equipment to minimize friction and shearing Positioning devices such as pillows, foam wedges, or pressure-reducing boots . Never use ring cushions, or donuts, because they increase venous pressure. Support surfaces are pressure-reducing or pressure-relieving devices. The most common support surfaces are seating devices (air, fluid foam, or gel cushions); air-, gel-, or water-filled mattress overlays; static flotation mattresses; alternating air mattresses; low–air-loss beds; and air-fluidized beds. 2. Wound care/ Wound management *** Wounds can be treated by leaving them open to air; no dressing (protective covering placed over a wound) is applied. Wounds left open to the air heal more slowly because wound drying produces a dried eschar or scab Closed wound care uses dressings to keep the wound moist, promoting healing. A moist environment is best for wound healing Generally, an ideal dressing should maintain a moist environment, be absorbent, provide thermal insulation, act as a bacterial barrier, reduce or eliminate pain at the wound site, and allow for painfree removal different types of dressings ( 1 st dressing should be 24-48 hrs) Provide physical, psychological, and aesthetic comfort Prevent, eliminate, or control infection Absorb drainage Maintain moisture balance of the wound Protect the wound from further injury Protect the skin surrounding the wound Debride (remove damaged/necrotic tissue), if appropriate Stimulate and/or optimize the healing response Consider ease of use and cost effectiveness always replace dressings with fresh dressings or reinforce the dressing with additional dressings before drainage causes saturation. b. Type of wound dressing (There are three basic types of primary dressings: those that maintain moisture, those that absorb moisture, and those that add moisture) table 32.5( should read) Gauze dressing (book): Dry gauze dressings can be used to cover wounds, commonly closed surgical wounds. Gauze dressings often consist of three layers. The first layer of dressing material applied directly to a draining wound, allows drainage from the wound to move into overlying absorbent layers of dressing, helping to prevent maceration and reinfection, stick to the wound. Material to absorb and collect drainage is then placed over the first layer of nonabsorbent material. This material acts as a wick, pulling drainage out by capillary action. Therefore, cotton-lined gauze sponges soak up more liquid than do unlined sponges. Fluffed and loosely packed dressings are more absorbent than tightly packed dressings. The top of the dressing may be further protected by surgical or abdominal pads (ABDs), which are thick, absorbent pads that help to absorb profuse drainage Nonadherent gauzes include sterile petrolatum gauze and Telfa gauze. Telfa’s shiny outer surface is applied to the wound. These dressings allow drainage to pass through and be absorbed by the outer absorbent layer, but prevent outer dressings from adhering to the wound and causing further injury when removed. These dressings are often used on incisions closed with sutures or staples. Special gauze dressings (e.g., Sof-Wick) are precut halfway to fit around drains or tubes Transparent films (e.g., OPSITE) are semipermeable membrane dressings that are adhesive and waterproof. This type of dressing is often used over peripheral intravenous sites, central venous access device insertion sites, and noninfected healing wounds + When caring for open wounds and pressure injuries, it is necessary to keep the wound tissue moist and the surrounding skin dry. +Autolytic debridement uses occlusive dressings, such as hydrocolloid or transparent films, and uses the body’s own enzymes and defense mechanisms to loosen and liquefy necrotic tissue. Enzymatic debridement involves the application of commercially prepared enzymes to speed up the body’s autolytic process +Mechanical debridement uses external physical force to dislodge and remove debris and necrotic tissue. This could be achieved by wound irrigation with pulsed pressure lavage (washing), whirlpool therapy, ultrasound or laser treatment, or with surgical debridement. C. Changing the dressing - If wound care is uncomfortable, administer a prescribed analgesic 30 to 45 minutes before changing the dressing. Provide privacy - If wound care is uncomfortable, administer a prescribed analgesic 30 to 45 minutes before changing the dressing. Among the most common causes of hospital-acquired infections is carelessness in practicing asepsis during dressing changes. D. Remove the dressing - Use standard precautions; E. Cleaning the wound ( approximate, top to down, un-approximate: circle, in to out) F. Apply the new dressing: apply skin barrier, topical medication G. Secure new dressing: tape, bandages and binders, and Montgomery straps. 3. Caring for patients with wound drain (***) a. OPEN DRAINAGE SYSTEMS A Penrose drain is soft and flexible. This drain does not have a collection device. It empties into absorptive dressing material, higher pressure to lower pressure It is not sutured in place. A sterile, large safety pin is often attached to the outer portion to prevent the drain from slipping back into the incised area Care is necessary to ensure that these drains are not dislodged during dressing changes. Sometimes the health care provider orders a Penrose drain that is to be shortened each day. To do so, grasp the end of the drain with sterile forceps, pull it out a short distance while using a twisting motion, and cut off the end of the drain with sterile scissors. Place a new sterile pin at the base of the drain, as close to the skin as possible. b. CLOSED DRAINAGE SYSTEMS Closed drainage systems consist of a drainage tube that may be connected to an electrical suction device or have a portable built-in reservoir to maintain constant low suction. Examples include Jackson–Pratt drainage tubes and Hemovacs These tubes are usually sutured to the skin. The closed drainage system prevents microorganisms from entering the wound from saturated dressings. Closed drainage systems also allow accurate measurement of drainage These systems must be emptied and the suction reestablished according to the directions for each device. Wear gloves when emptying the drainage and do not touch the open port to avoid contaminating the port 4.Collecting wound culture 5. Using additional tenique to promote wound healing - FIBRIN SEALANTS - NEGATIVE PRESSURE WOUND THERAPY (NPWT) - GROWTH FACTOR - HYPERBARIC OXYGEN THERAPY (HBOT) - HEAT AND COLD THERAPY 6. Removing sutures and staples 7. Teaching wound care at home 8. Document wound CHAP 37: URINARY ELIMINATION- 7 skills _ P 1380 A. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY B. FACTORS AFFECTING URINATION - Developmental considerations ( Toilet training, Effect of aging) - Food and fluid intake - Psychological - Activity and muscle tone - Pathologic condition - Medication + Abuse of analgesics, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, can cause nephrotoxicity. Some antibiotics, such as gentamicin, can be nephrotoxic as well. +Diuretics, which commonly are used in the treatment of hypertension and other disorders, prevent the reabsorption of water and certain electrolytes in the tubules +Cholinergic medications stimulate contraction of the detrusor muscle and produce urination +Some analgesics and tranquilizers suppress the central nervous system, interfering with urination by diminishing the effectiveness of the neural reflex. Certain drugs cause urine to change color, including the following: Anticoagulants may cause hematuria (blood in the urine), leading to a pink or red color. Diuretics can lighten the color of urine to pale yellow. Phenazopyridine, a urinary tract analgesic, can cause orange or orange-red urine. The antidepressant amitriptyline or B-complex vitamins can turn urine green or blue-green. Levodopa (L-dopa), an antiparkinson drug, and injectable iron compounds can lead to brown or black urine. C. NURSIG PROCESS FOR URINARY ELIMINATION I. ASSESSMENT 1. Nursing history: - A nursing history should include questions for the patient (or caregiver) about usual voiding habits and any current or past voiding difficulties. - Patients with urinary diversions may have established individualized personal care routines. A urinary diversion involves the surgical creation of an alternate route for excretion of urine 2. Physical assessment: - The physical assessment of urinary functioning includes an examination of the urinary bladder, urethral meatus, skin, and urine. The kidneys are normally well protected by considerable fat and connective tissue, making palpation difficult. - Bladder (bedside scanner with ultrasound) - Urinary Orifice - Skin integrity and hydration (abrasion) 3. Urine characteristics (table 37.1) 4. Special Assessment techniques (***): measuring urine output, collecting urine specimens, performing pointof-care urine testing, and assisting with diagnostic procedures. 1. Measuring the output Measuring the patient’s fluid intake and output is an important nursing responsibility. Gloves are required when handling urine to prevent exposure to pathogenic microorganisms or blood that may be present in the urine. Goggles also are worn due to urine splashing. a.Measuring output who are continent 1. Ask the patient to void into a bedpan, urinal, or specimen hat (container), either in bed or in the bathroom. Urinary devices used to collect or measure urine are shown in Figure 37-5. 2. Put on gloves. Pour the urine from the collection device into the appropriate measuring device provided by the facility. The devices are calibrated in milliliters. Collection devices may be calibrated for measurement, eliminating the need for an additional measuring device. 3. Place the calibrated container on a flat surface, such as a shelf, for an accurate reading. Reading at eye level, note the amount of urine voided and record it in the patient’s electronic record. Record the total amount voided during each shift. The total for the 24-hour period is usually calculated by the electronic documentation software. 4. Discard the urine in the toilet unless a specimen is required. If a specimen is required, pour the urine into an appropriate specimen container. b.Measuring output who are incontinent - Note the number of times the patient is incontinent and any notable urine characteristics, such as color and odor - Use of scheduled toileting (assisting the patient to the toilet to attempt to void on a regular basis, such as every 2 hours) can assist in obtaining urine for measurement, - Measurement of urinary output via weighing of absorbent pads has been used successfully to monitor urinary output in patients who are incontinent, as well as to reduce use of indwelling urinary catheters. The dry pad weight is subtracted from the wet pad weight. The resulting difference in gram weight is the converted to milliliters c.Measuring output w patient have indwelling catheter 1. Put on gloves. 2. Place a calibrated measuring device (Fig. 37-5) beneath the urine collection bag (Fig. 37-6). To prevent the spread of infection, patients should have their own calibrated measuring device. 3. Place the drainage spout from the collection bag above, but not touching, the calibrated measuring device, and open the clamp. 4. Allow the urine to flow from the collection bag into the measuring device. 5. Reclamp the drainage tube, wipe the spout of the tube with an alcohol pad, and replace the tube into the slot on the drainage bag. Proceed with measurement of urine as described earlier. 2. Collecting Urine Specimens a.Routine Urinalysis A sterile urine specimen is not required for a routine urinalysis. Collect urine by having the patient void into a clean bedpan, urinal. Take care to avoid contamination with feces. When patients are voiding into a bedpan or collection device on the toilet, instruct them not to place toilet tissue into the urine. Using aseptic technique, pour the urine into an appropriate container; label it with the patient’s name, date, and time of collection; Do not leave urine standing at room temperature for a long period before sending it to the laboratory; b.Clean-Catch mor midstream specimens (A clean-catch midstream urine specimen is considered a sterile specimen.) Most health care facilities specify that a clean-catch specimen be collected during midstream. This means that the patient voids and discards a small amount of urine; continues voiding in a sterile specimen container to collect the urine; stops voiding into container; removes container and continues voiding; then discards the last amount of urine in the bladder The first small amount of urine voided helps to flush away any organisms near the meatus because the findings may be inaccurate if these organisms enter the specimen urine voided at midstream is most characteristic of the urine the body is producing. c. Sterile specimen Sterile urine specimens may be obtained by catheterizing the patient’s bladder or by taking the specimen from an indwelling catheter already in place. When it is necessary to collect a urine specimen from a patient with an indwelling catheter, the specimen should be obtained from the catheter itself using the special port for specimens. Always observe sterile technique while collecting a urine specimen from an indwelling catheter Gather equipment, including a syringe, an antiseptic swab, a sterile specimen container, nonsterile gloves, and possibly a clamp. If urine is not present in the tube, clamp the tube below the access port briefly (not to exceed 30 minutes) to allow urine to accumulate. Clean the access port with an antiseptic swab, and carefully attach the syringe to the port (Fig. 37-7). Aspirate urine into the syringe, remove the syringe, release the clamp if one was used, and transfer the specimen to the appropriate container Label the specimen with the patient’s name, date, and time of collection; then package and transport d. Urine specimens for an urinary diversion Clean urine specimens can be obtained from a urinary diversion appliance into a clean container for a routine urinalysis Specimens for culture should never be obtained directly from the urostomy appliance The preferred method is to catheterize the stoma. Remove the stoma appliance and clean the stoma site with solution. Using sterile technique, insert the urinary catheter no more than 2 to 3 in into the stoma site. If there is resistance, rotate the catheter gently until it slides forward. If there is continued resistance, do not force the catheter. After collection of a sufficient amount of urine, remove the catheter and reapply the stoma appliance. e. 24- hour urine specimen Discard this urine and then collect all urine voided for the next 24 hours. At the end of the 24 hours, ask the patient to void. Add this urine to the previously collected urine, and then send the entire specimen to the laboratory. f. Specimen from children Plastic disposable collection bags are available for collecting urine specimens from infants and young children who have not achieved voluntary bladder control 3. Point-of care urine testing For example, a nurse may test urine for the presence of glucose, protein, bilirubin, bacteria, and blood. The results of the test are recorded on the patient’s record The nurse may also determine the specific gravity of urine, which is a measure of the density of urine compared with the density of water. The higher the number, the more concentrated the urine is, unless there are abnormal components, such as glucose or protein, in the urine. 4. Assisting with diagnostic procedure Urodynamic studies Cystoscopy Intravenous pyelogram Retrograde pyelogram Renal ultrasound Computer Tomography (CT scan) II. DIAGNOSING III. PLANNING IV. IMPLEMENTING (bang cho older adult for all disease) Nursing interventions focus on maintaining and promoting normal urinary patterns, improving or controlling urinary incontinence, preventing potential problems associated with bladder catheterization, and assisting with care of urinary diversions. 1. Promoting normal urination (***) Nursing care to promote normal urination includes interventions to support normal voiding habits, fluid intake, strengthening of muscle tone, stimulating urination and resolving urinary retention, and assisting with toileting Maintain normal voiding habit (schedule, urge to void, privacy, position, hand hygiene) Promoting fluid intake (drink 2000-2400 ml/ day, Monitor fluid intake for excessive amounts of caffeine-containing beverages, high-sodium beverages, and high-sugar beverages. Provide fresh water, juices, and fluids of preference to patients with alterations in mobility. Strengthen muscle tone: PFMT can improve voluntary control of urination and significantly reduce or eliminate problems with stress incontinence (involuntary loss of urine related to an increase in intraabdominal pressure) by strengthening perineal and abdominal muscle tone PFMT, often referred to as Kegel exercises, targets the inner muscles that lie under and support the bladder. These muscles can be toned, strengthened, and actually made larger by a regular routine of tightening and relaxing. Instruct patients to contract the pelvic floor muscles for 10 seconds and to relax them for 10 seconds. Encourage the patient to perform PFMT exercises without involving the muscles in the abdomen, inner thigh, and buttocks Assisting with toileting Commodes are chairs—straight-back chairs or wheelchairs with open seats and a shelf or a holder underneath that holds a bucket (Fig. 37-9). Commodes can be used for patients who can get out of bed but cannot use the bathroom toilet. Bedpan and Urinal: Male patients confined to bed usually use the urinal for voiding and the bedpan for defecation; female patients use the bedpan for both 2. Caring for patient with Urinary Tract Infection (***) Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the second most common type of infection in the body Women are especially vulnerable to UTIs because the female urethra is shorter and in closer proximity to the vagina and rectum. UTIs can affect both the upper urinary tract, involving the kidneys and ureters (pyelonephritis) and lower urinary tract, involving the bladder and urethra (cystitis). Escherichia coli, bacteria commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract, are the most common causal organism a.Risk factors Sexually active women: During intercourse, perineal bacteria can migrate into the urethra and bladder. Women who use diaphragms for contraception: The spermicide used with a diaphragm decreases the amount of normally protective vaginal flora. Postmenopausal women: Urinary stasis, which is common at this age, provides an optimal environment for bacteria to multiply; in addition, decreased estrogen contributes to loss of protective vaginal flora. People with an indwelling urinary catheter in place: Bacteria travel through or around the catheter and into the bladder. UTIs are the most common type of health care-associated infection (HAI), People with diabetes mellitus: Changes in the body’s defense system related to diabetes may increase the risk for UTIs). Older adults: The physiologic changes associated with aging (listed earlier in the chapter) predispose older people to the development of UTIs. In addition, enlargement of the prostate as men age can contribute to the development of UTIs in older men b. Diagnostic evaluation - In addition to the nursing history and physical examination, laboratory findings can identify the presence of a UTI. A urine sample from a clean-catch or sterile specimen - A C&S is positive if it shows at least 100,000 organisms per milliliter of urine. Lower counts may be considered clinically significant if the patient has signs and symptoms of a UTI - The presence of bacteria in a clean-catch midstream or sterile urine specimen, accompanied by symptoms (e.g., dysuria, urinary frequency or urgency, or cloudy urine with a foul odor), indicates a UTI. - Red blood cells and nitrates also may be present in the urine. C. Treatment - Various protocols are used to treat UTIs. A short-course antibiotic regimen (one large dose vs. 3 or 7 days of smaller doses) usually eradicates infections of the lower urinary tract; longer antimicrobial therapy is required for upper UTIs Drink 8 to 10 8-oz glasses of water daily. Observe the urine for color, amount, odor, and frequency. Report any sign of infection to your health care provider. Dry the perineal area after urination or defecation from the front to the back, or from the urethra toward the rectum. Drink two glasses of water before and after sexual intercourse and void immediately after intercourse. Take showers rather than baths. Wear underwear with a cotton crotch, and avoid clothing that is tight and restrictive on the lower half of the body. 3. Caring for patient with Incontinence urination (***) It is one of the most common chronic health problems Urinary incontinence is more prevalent in women and increases with age. a. Type of urinary incontinence - Transient incontinence appears suddenly and lasts for 6 months or less. It is usually caused by treatable factors, such as confusion secondary to acute illness, infection, and as a result of medical treatment, such as the use of diuretics or intravenous fluid administration. - Stress incontinence (discussed earlier in the chapter) occurs when there is an involuntary loss of urine related to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. This commonly occurs during coughing, sneezing, laughing, or other physical activities. Childbirth, menopause, obesity, or straining from chronic constipation can also result in urine loss. - Urge incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine that occurs soon after feeling an urgent need to void (urgency). These patients experience a loss of urine before getting to the toilet and an inability to suppress the need to urinat - mixed incontinence indicates that there is urine loss with features of two or more types of incontinence - Overflow incontinence, or chronic retention of urine, is the involuntary loss of urine associated with overdistention and overflow of the bladder. The signal to empty the bladder may be underactive or absent, the bladder fills, and dribbling occurs. It may be due to a secondary effect of some drugs, fecal impaction, or neurologic conditions. - Functional incontinence is urine loss caused by the inability to reach the toilet because of environmental barriers, physical limitations, loss of memory, or disorientation. - Patients with reflex incontinence experience emptying of the bladder without the sensation of the need to void. Spinal cord injuries may lead to this type of incontinence. - Total incontinence is a continuous and unpredictable loss of urine, resulting from surgery, trauma, or physical malformation. Urination cannot be controlled due to an anatomic abnormality. a. Assessment (dietary habit, voiding record, palpate abdomen for distended bladder) The postvoid residual (PVR) urine (the amount of urine remaining in the bladder immediately after voiding) can be measured by the use of a portable ultrasound device that scans the bladder. A PVR of less than 50 mL indicates adequate bladder emptying. A PVR of greater than 100 mL is an indication the bladder is not emptying correctly INCONTINENCE-ASSOCIATED DERMATITIS Erythema, maceration, denuding, and inflammation occur as a result of exposure to urine or stool and may affect the skin of the perineum, perianal area, buttocks, inner thighs, sacrum, and coccyx Lesions may be present, including vesicles, bullae, papules, or pustules. The epidermis may be damaged to varying depths, with patients reporting discomfort, pain, burning, itching, or tingling Avoid using soap and hot water due to change in pH b. Treatment - Patients frequently turn to absorbent products for protection when they are incontinent - Many types of disposable and reusable products are available, including perineal pads or liners, protective underwear, guards and drip collection pouches, and adult briefs (continence pads - When voluntary control of urination is difficult or not possible for male patients, an alternative to an indwelling catheter is the urinary sheath or external condom catheter. Nursing care of a patient with a urinary sheath includes vigilant skin care to prevent excoriation. Remove the condom daily and wash the penis with soap and water, dry it carefully, and inspect the skin for irritation. Treatment Options for Urinary Incontinence Behavioral Techniques Pelvic floor muscle training exercises: Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) exercises (Kegel exercises) can be used to strengthen pelvic floor muscles and sphincter muscles. PFMT exercises can be done alone, with weighted cones, or with biofeedback. Biofeedback: Measuring devices are used to help the patient become aware of when pelvic floor muscles are contracting. Electrical stimulation: Electrodes are placed in the vagina or rectum that then stimulate nearby muscles to contract. Timed voiding or bladder training: May be used with biofeedback. Patient keeps track of when voiding and leaking occur to enable oneself to plan when to void, with increasing length of voiding intervals. Bladder training involves biofeedback and muscle training. Urgency control is addressed using distraction and relaxation techniques. Pharmacologic Treatment Treatment is dependent on the type of incontinence. Some medications inhibit contractions of the bladder, others may relax muscles, and some tighten muscles at the bladder neck and urethra. Topical estrogen may be used in postmenopausal women to relieve atrophy of involved muscles. Collagen may be injected into the tissue around the urethra to add bulk and help close the urethral opening. Mechanical Treatment Pessaries: A stiff ring that is inserted into the vagina, where it helps to reposition the urethra. The pessary may be placed by the patient or by a nurse. External barriers: Adhere to the urethral opening to stop urine leakage. The barrier is a small foam pad placed over the urethral opening. It seals against the body to keep urine from leaking. It is removed and discarded before the patient voids. Urethral insert: Small device, like a plug, that fits into the urethra. Removed to void, the insert is replaced until the patient needs to void again. Surgical intervention: Used as a last resort. Type of surgery depends on cause of incontinence. 4. Catherizing bladder a. REASONS FOR URINARY CATHETERIZATION Relieving urinary retention. Obtaining a sterile urine specimen when the patient is unable to voluntarily void. Accurate measurement of urinary output in critically ill patients. Assist in healing open sacral or perineal wounds in incontinent patients. Emptying the bladder before, during, or after select surgical procedures Provide improved comfort for end-of-life care. Prolonged patient immobilization (potentially unstable thoracic or lumbar spine, multiple traumatic injuries). b. IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT THE LOWER URINARY TRACT The bladder is normally a sterile cavity. The external opening to the urethra can never be sterilized. The bladder has defense mechanisms. It empties itself of urine regularly and maintains an acidic environment, which has antibacterial advantages. These help to maintain a sterile bladder under normal circumstances and also help in clearing an infection if it occurs. Pathogens introduced into the bladder can ascend the ureters and cause bladder and kidney infections. A healthy bladder is not as susceptible to infection as an injured one. A state of lowered resistance, present in many health conditions and stressful situations, predisposes the patient to urinary infection. C. TYPES OF CATHETERS - Intermittent urethral catheters, or straight catheters, are used to drain the bladder for shorter periods. Intermittent catheterization should be considered as an alternative to short-term or long-term indwelling urethral catheterization to Reduce catheter-associated UTI - If a catheter is to remain in place for continuous drainage, an indwelling urethral catheter is used. Indwelling catheters are also called retention or Foley catheters. Indwelling catheters are used for the gradual decompression of an overdistended bladder, for intermittent bladder drainage and irrigation, and for continuous bladder drainage. The indwelling catheter has more than one lumen (open tube) within the catheter. In a double-lumen catheter, one lumen is connected directly to the balloon, which is inflated with sterile water; the other is the lumen through which the urine drains - A suprapubic catheter is used for long-term continuous drainage. This type of catheter is inserted surgically through a small incision above the pubic area (Fig. 37-12). Suprapubic bladder drainage diverts urine from the urethra when injury, stricture, prostatic obstruction, or gynecologic or abdominal surgery has compromised the flow of urine through the urethra - If a chronically ill patient requires long-term continuous drainage, a suprapubic catheter is the best choice, as it is less apt to introduce pathogens and result in urinary tract infection or sepsis. - The most common patient position for catheter insertion is the dorsal recumbent position, with the patient preferably on a solid surface, such as a firm mattress or a treatment table. The Sims’, or lateral, position is an alternate position for catheter insertion in female patients D. CATHETER-ASSOCIATED HARM - Urinary tract infection, trauma, pain and bladder spasm, and sepsis are some of the hazards associated with introducing an instrument such as a catheter into the bladder - When the catheter is left in place, the organisms may move up the catheter lumen or the space between the catheter and the urethral wall. This asymptomatic condition in which bacteria are present in the urine is known as bacteriuria. E.CARING FOR PATIENT WITH URINARY CATHETER (***) Wash hands before and after caring for the patient. Clean the perineal area thoroughly, especially around the meatus, daily and after each bowel movement. Cleanse the catheter by cleaning gently from the meatus outward. Use mild soap and water or a perineal cleanser to clean the perineal area; rinse the area well. Do not use powders and lotions after cleaning. Do not use antibiotic or other antimicrobial cleaners or betadine at the urethral meatus Make sure that the patient maintains a generous fluid intake, This helps prevent infection and irrigates the catheter naturally by increasing urine output. Encourage the patient to be up and about, as ordered. Note the volume and character of urine, and record observations carefully. Observe the urine through the drainage tubing and in the collecting container. Note and record the amount of urine on the patient’s intake-and-output record every 8 hours. Empty the urine into a graduated container that is calibrated accurately for correct determination of output. Do not open the drainage system to obtain urine specimens or to measure urine. If the tubing becomes disconnected and the sterile closed drainage system has been compromised, replace the catheter and collecting system .When emptying the drainage bag, make sure the drainage spout does not touch a contaminated surface. Teach the patient the importance of personal hygiene—especially the importance of careful cleaning after having a bowel movement—and thorough, frequent hand hygiene. Promptly report any signs or symptoms of infection. These include a burning sensation and irritation at the meatus, cloudy urine, a strong odor to the urine, an elevated temperature, and chills. Help the patient take a shower bath if possible. Remember to keep the collecting bag lower than the bladder to promote drainage. Consider evidence-based practice guidelines and facility policy to ensure that the catheter is removed at the earliest time possible, to limit use to the shortest duration possible Change indwelling catheters only as necessary. The interval between catheter changes varies and should be individualized for the patient, based on clinical symptoms: catheter encrustations, obstruction, leakage, bleeding, and catheter-associated UTIs Patients who required long-term use of an indwelling catheter for persistent urinary retention may experience self-care practice and catheter challenges. See the accompanying Research in Nursing display (on page 1370) for a discussion of an intervention that may assist patients in preventing and addressing catheter-related problems. F. TEACHING, IRRIGATING, REMOVE ( BOOK) 5. Caring for a Patient With a Urologic Stent 6. Caring for a Patient With a Urinary Diversion 7. Caring for a Patient Receiving Dialysis CHAP 38: BOWEL ELIMINATION – 5 SKILLS P 1450 A. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY B. FACTORS AFFECTING BOWEL ELIMINATION Constipating foods: processed cheese, lean meat, eggs, pasta, rice, white bread, iron and calcium supplements (Day, Wills, & Coffey, 2014) Foods with laxative effect: certain fruits and vegetables (e.g., prunes), bran, chocolate, spicy foods, alcohol, coffee Gas-producing foods: onions, cabbage, beans, cauliflower + Pathologic: Any drug with the potential to cause gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., anticoagulants, aspirin products) may cause the stool to appear pink to red to black. Iron salts result in a black stool from the oxidation of iron. Bismuth subsalicylate used to treat diarrhea can also cause black stools. Antacids may cause a white discoloration or speckling in the stool. Antibiotics may cause a green-gray color related to impaired digestion. Diarrhea or constipation may result from pathologic conditions such as diverticulitis (inflammation and/or infection of a diverticulum, a small, bulging pouch in the colon). Diarrhea may result from bacterial and viral infection, malabsorption syndromes (the inability of the digestive system to absorb one or more of the major vitamins, minerals, or nutrients), neoplastic diseases (tumors), diabetic neuropathy (damage to nerve cells), hyperthyroidism, and uremia (retention of urea in the blood). For example, infections caused by certain types of Escherichia coli, life-threatening hematologic and renal complications. Severe abdominal cramping followed by watery or bloody diarrhea may signal a microbial infection, which can be confirmed by a stool sample. Constipation may be the result of conditions such as diseases within the colon or rectum and injury to, or degeneration of, the spinal cord and megacolon (extremely dilated colon). Intestinal obstruction occurs when blockage prevents the normal flow of intestinal contents through the intestinal tract. Mechanical obstructions result from pressure on the intestinal walls. Common causes of mechanical obstruction are tumors of the colon or rectum, diverticulum, adhesions from scar tissue, stenosis, strictures, and hernia and volvulus (twisting of a part of the colon). Nonmechanical obstructions result from an inability of the intestinal musculature to move the contents through the bowel. Examples of causes of nonmechanical obstruction include diseases that weaken or paralyze the intestinal walls such as muscular dystrophy, diabetes mellitus, and Parkinson’s disease. + MEDICATIONS: Medications are available that can promote peristalsis (laxatives) or inhibit peristalsis (antidiarrheal medications). Opioids are a common cause of medication-induced constipation and can result in significant distress for the patient. The enteric neurons control major body functions such as bowel control. Antacids containing aluminum, iron sulfate, and anticholinergic medications also decrease gastrointestinal motility, with the potential to also cause constipation. For example, diarrhea is a potential adverse effect of treatment with antibiotics such as amoxicillin clavulanate. Medications with magnesium, such as over-the-counter antacids, can also cause diarrhea. Metformin, a common medication used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus, can cause diarrhea. Because antibiotics are used so extensively in the health care setting, many patients are at risk for infection with Clostridium difficile, a health care–acquired infection (HAI) C. difficile causes intestinal mucosal damage and inflammation, resulting in diarrhea and abdominal cramping. C. difficile spores are shed in feces and are relatively resistant to disinfectants It is important to institute contact precautions for infected patients. C. NURSING PROCESS FOR BOWEL ELIMININATION I. ASSESSMENT 1.Nursing history 2.Physical assessment - Abdomen: The sequence for abdominal assessment proceeds from inspection, auscultation, and percussion to palpation. Inspection and auscultation are performed before palpation because palpation may disturb normal peristalsis and bowel motility. Place the patient comfortably in the supine position with the abdomen exposed, the chest and pubic area draped, and the knees slightly flexed. Encourage the patient to urinate prior to the examination so that the bladder is empty. - Inspection Observe the contour of the abdomen, noting any masses, scars, or areas of distention Observe the contour of the abdomen. Significant findings may include the presence of distention (inflation) or protrusion (projection). -Auscultation Using the diaphragm of a warmed stethoscope, listen for bowel sounds in all abdominal quadrants, using a systematic, clockwise approach. If the patient has a nasogastric (NG) tube in place, disconnect it from suction during this assessment to allow for accurate interpretation of sounds. Note the frequency and character of bowel sounds, intermittent audible clicks and gurgles produced by the movement of air and flatus in the gastrointestinal tract. They are usually highpitched, gurgling, and soft, indicating bowel motility and peristalsis Significant findings include hypoactive bowel sounds, a diminished rate of sounds; Hypoactive bowel sounds indicate diminished bowel motility, commonly caused by abdominal surgery or late bowel obstruction hyperactive bowel sounds, intense with increased frequency; Hyperactive bowel sounds indicate increased bowel motility, commonly caused by diarrhea, gastroenteritis, or early/partial bowel obstruction. Decreased or absent bowel sounds, evidenced only after listening for 2 minutes or longer, signify the absence of bowel motility, commonly associated with peritonitis, paralytic ileus, and/or prolonged mobility - Palpation Perform light palpation in each quadrant. Use warm hands and bend the patient’s knees Palpate each quadrant in a systematic manner, noting muscular resistance, tenderness, enlargement of the organs, or masses. If the patient complains of abdominal pain, palpate the area of pain last. If the patient’s abdomen is distended, note the presence of firmness or tautness. ANUS AND RECTUM Perform a superficial examination each time you wash a patient’s anal area or assist with bowel evacuation. Inspection is used to assess the anal area, which normally has increased pigmentation and some hair growth. Assess for lesions, ulcers, fissures (linear break on the margin of the anus), inflammation, and external hemorrhoids (dilated veins appearing as reddened protrusions). Assess for the appearance of internal hemorrhoids or fissures. 3. STOOL CHARACTERISTICS (TABLE) 4. DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES: 1. Stool collection (***) Void first, because the laboratory study may be inaccurate if the stool contains urine. Defecate into the required container, such as clean or sterile bedpan or the bedside commode (depending on the specimen required), rather than the toilet, because the water in the toilet bowl may affect the analysis results. Do not place toilet tissue in the bedpan or specimen container because contents in the paper may influence laboratory results. Avoid contact with soaps, detergents, and disinfectants as these may affect test results. Notify the nurse when the specimen is available, so that it may be collected and transported to the laboratory as required. a. Stool culture: Culture of stool is indicated when there is suspected infection from bacteria, virus, fungi, or parasites b. Occult blood Certain conditions, such as ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disorders, and colon cancer, place the patient at high risk for intestinal bleeding In general, black stools indicate upper gastrointestinal bleeding, such as from a peptic ulcer, due to a reaction between hemoglobin and gastric acid. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding, such as from hemorrhoids or a polyp, may produce bright-red blood in the stool. Occult blood in the stool (blood that is hidden in the specimen or cannot be seen on gross examination) can be detected with screening tests. Fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) is used to detect occult blood in the stool. It is used for initial screening for disorders such as cancer and for gastrointestinal bleeding in conditions such as ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disorders, and intestinal polyps. The guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) is a chemical test that detects the enzyme peroxidase in hemoglobin molecules when blood is present in the stool sample The ingestion of vitamin C can produce false-negative results even if bleeding is present. The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) uses antibodies directed against human hemoglobin to detect blood in the stool. A positive FIT is more specific for bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract c. Timed specimens Consider the first stool passed by the patient as the start of the collection period. Collect the required volume of every stool passed within the designated period d. Specimen for Pinworm Adult pinworms, parasitic intestinal worms, live in the cecum The most common symptom of a pinworm infection is perianal itching Collect this specimen in the morning, immediately after the patient awakens and before the patient urinates, has a bowel movement, or a bath Use clear cellophane tape to collect a specimen for pinworms; frosted tape makes examination difficult 2.Direct visualize studies Endoscopy is the direct visual examination of body organs or cavities. Most commonly, this is done using a fiberoptic endoscope, a long, flexible tube containing glass fibers that transmit light into the organ and return an image that can be viewed. An endoscope enables the health care provider to view the integrity of the mucosa, blood vessels, and specific organ parts and is helpful for diagnosing inflammatory, ulcerative, and infectious diseases; benign and malignant neoplasms; and other lesions of the esophageal, gastric, and intestinal mucosa. Endoscopic studies include the following: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): visual examination of the esophagus, the stomach, and the duodenum Colonoscopy: visual examination of the large intestine from the anus to the ileocecal valve Sigmoidoscopy: visual examination of the sigmoid colon, the rectum, and the anal canal 3. Indirect visualize studies Indirect visualization of the gastrointestinal tract is commonly performed through radiography. The passage of x-rays through the patient creates a radiograph or film depicting body structures. This technique is useful for detecting obstructions, strictures, inflammatory disease, tumors, ulcers, and other lesions, and for diagnosing a hiatal hernia and other structural changes in the gastrointestinal tract. 4.Scheduling for diagnostic studies 1. Follow a logical sequence when more than one test is required for accurate diagnosis: Fecal occult blood tests: to detect gastrointestinal bleeding Barium studies: to visualize gastrointestinal structures and reveal any inflammation, ulcers, tumors, strictures, or other lesions Endoscopic examinations: to visualize an abnormality, locate a source of bleeding, and if necessary provide biopsy tissue samples 2. A barium enema and routine radiography should precede an upper gastrointestinal series because retained barium from an upper gastrointestinal series could take several days to pass through the gastrointestinal tract and cloud anatomic detail on the barium enema studies. 3. Noninvasive procedures usually take precedence over invasive procedures, such as endoscopic studies, when sufficient diagnostic data can be obtained from them. In some instances, endoscopic studies may be done before barium studies to ensure visualization. 4. It is important to consider any comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, that the patient may have in scheduling diagnostic studies that require the patient to have an altered diet or to have nothing by mouth. II. DIAGNOSING III. PLANNING IV. IMPLEMENTING 1.Promoting regular bowel habit (***) Promote regular bowel habits in well and ill patients by attention to timing, positioning, privacy, nutrition, and exercise. TIMING: Encourage toileting at the patient’s usual time during the day. This is often about an hour after meals, when mass colonic peristalsis occurs. POSITIONING: Sitting upright on a toilet or commode promotes defecation. An elevated toilet seat may be ordered for patients with orthopedic problems who cannot lower themselves to a toilet seat. Sitting upright promotes a sense of normalcy and the effects of gravity help to promote regular bowel movements. It is best to avoid bedpan use; encourage use of the toilet or bedside commode PRIVACY: Because most people consider elimination a private act, always respect the patient’s need to be alone while defecating, unless the patient’s condition makes this impossible NUTRITION: General dietary recommendations to promote regular defecation include a fluid intake of 2,000 to 3,000 mL and high-fiber intake. Water is recommended as the fluid of choice because fluids containing large amounts of caffeine and sugar may have a diuretic effect. It is important to be aware of those patients, particularly older adults with cardiac and renal problems, for whom increased fluid intake may be contraindicated. Increasing fiber intake without sufficient fluid intake can result in severe gastrointestinal problems, including fecal impaction EXERCISE Abdominal setting: The patient, lying in a supine position, tightens and holds the abdominal muscles for 6 seconds and then relaxes them. Repeat several times each waking hour. Thigh strengthening: The thigh muscles are flexed and contracted by slowly bringing the knees up to the chest one at a time and then lowering them to the bed. Perform this exercise several times for each knee each waking hour. 2.Providing comfort measures Comfort measures related to defecation include working with the patient to develop a bowel elimination routine that results in the easy passage of a soft, formed stool Encouraging recommended diet (if pertinent) and exercise Using medications, such as laxatives and antidiarrheals, only as needed if nonpharmacologic interventions are not effective Applying ointments or astringents (witch hazel) to inflamed and irritated tissue around the anal opening 3.Preventing and treating constipation (***) Constipation is dry, hard stool; persistently difficult passage of stool; and/or the incomplete passage of stool. People at high risk for constipation include patients on bedrest or with decreased mobility. In addition, those taking medications that cause constipation (e.g., opioids, anticholinergics); patients with reduced fluids, bulk, or fiber in their diet; people who are depressed; and patients with central nervous system disease or local lesions that cause pain while defecating are also at risk A. TEACHING ABOUT NUTRITION A combination of high-fiber foods (20 to 35 g of fiber), 60 to 80 oz (1.8 to 2.4 L) of fluid daily, and exercise has been shown to be effective in controlling constipation Foods that contain high amounts of fiber include bran, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. B. TEACHING ABOUT LAXATIVES Laxatives are drugs that induce emptying of the intestinal tract. Bulk-forming laxatives such as psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid work by absorbing water into the intestine to soften the stool and increasing stool bulk Osmotic laxatives are not absorbable and work by bringing water into the intestine Stimulant laxatives, such as bisacodyl and senna, improve defecation by increasing motility through irritation of the intestinal mucosa and increased water in the stool Saline-osmotic laxatives act by drawing water into the intestines, stimulating peristalsis, and are effective but should be used in caution in those patients with renal disease. Magnesium hydroxide has antacid properties in small dosages and laxative properties in larger doses. Because of their chemical action, laxatives should not be taken when a patient is experiencing abdominal pain. 4.Preventing and treating diarrhea (***) Diarrhea, in adults, is the passage of more than three loose stools a day. Diarrhea is often associated with intestinal cramps. Nausea and vomiting may occur; blood also may be noted. If diarrhea is untreated, this loss of fluids and electrolytes places the person at high risk for life-threatening complications. If oral intake is possible, teach patients to avoid cold fluids, fluids high in sugar, and rich foods, especially sweets, and to eat bland food in small portions. A. TEACHING ABOUT FOOD SAFETY Never use raw eggs in any form because of the danger of infection with Salmonella bacillus. Give only pasteurized fruit juices to small children. B. TEACHING ABOUT TRAVELING DIARRHEA Traveler’s diarrhea, caused by bacterial enteropathogens, viruses, or parasites, is the most predictable travel-related illness Symptoms include more than three loose stools in a 24-hour period, fever, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps and/or pain. Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) is often recommended as a prophylaxis for traveler’s diarrhea C.TREATMENT 5. Decreasing Flatulence Excessive formation of gases in the stomach or intestines is known as flatulence. When the gas is not expelled but accumulates in the intestinal tract, the condition is referred to as intestinal distention or tympanites Gas-producing foods, such as beans, cabbage, onions, cauliflower, and beer, often predispose a person to flatulence and distention. Flatulence associated with weight loss, fever, loss of appetite, or change in bowel habits should be evaluated for the presence of conditions such as malabsorption. 6. Emptying the colon of feces(***): Several methods are used to help promote elimination of feces: enemas, suppositories, oral intestinal lavage, and digital removal of stool. A.ENEMAS (***) An enema is the introduction of a solution into the large intestine, usually to remove feces. The instilled solution distends the intestine and irritates the intestinal mucosa, thus increasing peristalsis. Enemas are generally classified as cleansing or retention enemas. Rectal agents and manipulation, including enemas, are discouraged for use with myelosuppressed patients and/or patients at risk for myelosuppression and mucositis because they can lead to development of bleeding, anal fissures, or abscesses, which are portals for infection Enemas should also be avoided in those with bowel obstruction or paralytic ileus as they can increase the risk of perforation. +Cleansing Enemas Relieve constipation or fecal impaction Prevent involuntary escape of fecal material during surgical procedures Promote visualization of the intestinal tract by radiographic or instrument examination Help establish regular bowel function during a bowel-training program The most common types of solutions used for cleansing enemas are tap water, normal saline solution, soap solution, and hypertonic solution. Hypotonic (tap water) and isotonic (normal saline solution) enemas are large-volume enemas that result in rapid colonic emptying. However, using such large volumes of solution (adults, 500 to 1,000 mL; infants, 150 to 250 mL) may be dangerous for patients with weakened intestinal walls, such as those with bowel inflammation or bowel infection. Hypertonic solution preparations are available commercially and are administered in smaller volumes They may be contraindicated in patients for whom sodium retention is a problem. They are also contraindicated for patients with renal impairment or reduced renal clearance because such patients have compromised ability to excrete phosphate adequately, with resulting hyperphosphatemia +Retention Enemas Oil-retention enemas: lubricate the stool and intestinal mucosa, making defecation easier. About 150 to 200 mL of solution is administered to adults. Carminative enemas: help to expel flatus from the rectum and provide relief from gaseous distention. Common solutions include the milk and molasses enema (equal parts) and the magnesium sulfate– glycerin–water (MGW) enema (30 mL of magnesium sulfate, 60 mL of glycerin, and 90 mL of warm water). Medicated enemas: provide medications that are absorbed through the rectal mucosa. Anthelmintic enemas: destroy intestinal parasites. +Equipment enema kits include a flexible bottle containing hypertonic solution with an attached, prelubricated firm tip about 5 to 7.5 cm Tap water, saline solution, and soap solution enemas are administered using a container, rubber or plastic tubing with side openings near its distal end, a tubing clamp, lubricant, and the prescribed solution +Patient Preparation A reclining position for enema administration—specifically left side–lying with the upper thigh pulled toward the abdomen if possible, or the knee–chest position—is recommended, but if the patient has a respiratory disorder or is having difficulty breathing, elevate the head of the bed slightly Avoid Fowler’s position because the solution will remain in the rectum and expulsion will occur rapidly, resulting in minimal cleansing. +Administration: Do not warm the hypertonic solution Administration of an Oil-Retention Enema A small rectal tube is used. The small size helps to reduce intestinal contractions so that the patient can retain the oil more easily. Oil enemas are available in commercial kits similar to those for hypertonic-solution enemas. The kits contain a small rectal tube. Administer the oil-retention enema at body temperature to minimize muscle contractions caused by a warmer or cooler solution. Instruct the patient to retain the oil for at least 30 minutes for best cleansing results. A cleansing enema is often ordered after an oil-retention enema to facilitate emptying of the bowel. B.RECTAL SUPPOSITORY (***) suppository is a conical or oval solid substance shaped for easy insertion into a body cavity and designed to melt at body temperature. Suppositories can be used to stimulate the bowel in a constipated patient. Retention suppositories deliver drug therapy and can be used to deliver medications such as antipyretics when the patient is unable to take them orally. C.ORAL INTESTINAL LAVAGE Oral solutions, such as GoLYTELY or Colyte, which are polyethyl glycol solutions (PEG), can be used to cleanse the intestine of feces. for visualization purposes or as a “bowel prep” before intestinal surgery. Evacuation of feces usually begins within 1 hour after the first glass and is completed within 4 to 6 hours A clear diet for 24 hours before taking this solution lessens the time needed for completion of the bowel prep, but potassium replacement may be required before surgery because of the limited potassium in a clear diet. Use of hyperosmotic solutions, such as magnesium citrate, is discouraged, as is the use of sodium phosphate, which is generally contraindicated in those with renal disease and at high risk for electrolyte imbalances. D.DIGITAL REMOVAL OF STOOL (***) Fecal impaction, most often caused by constipation, prevents the passage of normal stools. Patients who use frequent stimulant laxatives, those who are immobile, and patients who have spinal cord injury, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, malignancies, and chronic kidney disease are also at high risk Include dietary interventions, adequate fluids, and adjustment of medication in the patient’s care plan before considering digital removal of feces This procedure is very uncomfortable and may cause great discomfort to the patient as well as irritation of the rectal mucosa and bleeding. Digital removal of a fecal mass can stimulate the vagus nerve, resulting in a slowed heart rate. If this occurs, stop the procedure immediately, monitor the patient’s heart rate and blood pressure, and notify the primary health care provider. Many patients find that a sitz bath or tub bath after this procedure soothes the irritated perineal area. order an oil-retention enema to be given before the procedure to soften stool. 7. Managing Bowel Incontinence Bowel incontinence is the inability of the anal sphincter to control the discharge of fecal and gaseous material. The cause of incontinence is often related to changes in the function of the rectum and anal sphincter related to aging, neurologic disease, and childbirth Note when incontinence is most likely to occur, and assist the patient to the bathroom Keep the skin clean and dry by using proper hygienic measures. Apply a protective skin barrier after cleaning the skin, Change bed linens and clothing as necessary to avoid odor, skin irritation, and embarrassment. Confer with the primary care provider about using a suppository or a daily cleansing enema. +INCONTINENCE-ASSOCIATED DERMATITIS Erythema, maceration, denuding, and inflammation occur as a result of exposure to urine or stool and may affect the skin of the perineum, perianal area, buttocks, inner thighs, sacrum, and coccyx + INDWELLING RECTAL TUBE (***) In some health care facilities, a fecal management system (or, bowel management systems with an indwelling rectal catheter) is used for patients with uncontrollable diarrhea. Disadvantages of indwelling rectal tubes include leakage and perirectal skin damage, injury to the rectal mucosa, and injury of the anal sphincter. + FECAL INCONTINENCE DEVICE Use of a fecal incontinence collection device provides the means to protect perianal skin from repeated episodes of fecal incontinence (Powers & Zimmaro Bliss, 2012). This device can be secured via adhesive around the anal opening and attached to gravity drainage, allowing liquid stool to accumulate in a collection bag It is best applied before the perianal area becomes excoriated. If excoriation is already present, application of a skin barrier prior to applying the pouch can be effective 8. Designing and Implementing Bowel-Training Programs 9. Maintaining a Nasogastric Tube An NG tube is a pliable single- or double-lumen (inner open space) tube that is hollow, allowing for the removal of gastric secretions and instillation of solutions such as medications or feedings into the stomach NG tubes may be inserted to decompress or drain the stomach of fluid or unwanted stomach contents such as poison or medication and air, and when conditions are present in which peristalsis is absent. The Levine tube is a common single-lumen tube (Fig. 38-8). It lacks a venting system, and mucosal damage can occur when suction is applied continuously. PROMOTING PATIENT SAFETY To promote patient safety when instilling solutions into an NG tube, tube placement must be verified before administration of any fluids or medications. This ensures that the tip of the tube is situated in the stomach or intestine, preventing inadvertent administration of substances into the wrong place A misplaced feeding tube in the lungs or pulmonary tissue places the patient at risk for aspiration. PROVIDING COMFORT MEASURES Patients with NG tubes often experience discomfort related to irritation to nasal and throat mucosa, and drying of the oral mucous membranes. Administer oral hygiene frequently, as often as every 2 to 4 hours, to prevent drying of tissues and to relieve thirst. 10. Meeting the Needs of Patients With Bowel Diversions (***) Patients sometimes undergo surgical procedures to create an opening into the abdominal wall for fecal elimination. The word ostomy is a term for a surgically formed opening from the inside of an organ to the outside. An ileostomy allows liquid fecal content from the ileum of the small intestine to be eliminated through the stoma. A colostomy permits formed feces in the colon to exit through the stoma (the opening of the ostomy attached to the skin). A surgical intervention that does not involve an external stoma is the restorative proctocolectomy ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA), also called a J pouch or an internal pouch. This procedure is commonly considered for use in those patients with inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis COLOSTOMY AND ILEOSTOMY CARE (***) The patient with an ostomy needs physical and psychological support both preoperatively and postoperatively Keep the patient as free of odors as possible. Empty an ostomy appliance that can be drained thereby reducing the risk of leakage and potential Inspect the patient’s stoma regularly. It should be dark pink to red and moist (Fig. 38-11). A pale stoma may indicate anemia (Fig. 38-12A), and a dark or purple-blue stoma may reflect compromised circulation or ischemia. Bleeding around the stoma and its stem should be minimal. Notify the primary care provider promptly if bleeding Note the size of the stoma, which usually stabilizes within 6 to 8 weeks. Most stomas protrude ½ to 1 in from the abdominal surface and may initially appear swollen and edematous. If an abdominal dressing is in place at the surgical incision, check it frequently for drainage and bleeding. The dressing is usually removed after 24 hours. Keep the skin around the stoma site (peristomal area) clean and dry. A leaking appliance frequently causes skin erosion. Candida or yeast infections around the stoma if not kept dry. Measure the patient’s fluid intake and output. Check the ostomy appliance for the quality and quantity of discharge. Initially after surgery, peristalsis may be inhibited. As peristalsis returns, stool will be eliminated from the stoma. Record intake and output every 4 hours for the first 3 days after surgery. If the patient’s output decreases while intake remains stable, report the condition promptly. Explain each aspect of care to the patient and explain what the patient’s role will be when beginning selfcare. Encourage the patient to participate in care and to look at the ostomy. Patients normally experience emotional depression during the early postoperative period. Help the patient cope by listening, explaining, and being available and supportive. Irrigating a Colostomy Irrigations are used to promote regular evacuation of distal colostomies. Colostomy irrigation may be indicated in patients who have a left-sided end colostomy in the descending or sigmoid colon, are mentally alert, have adequate vision, and have adequate manual dexterity needed to perform the procedure Contraindications include IBS, peristomal hernia, postradiation damage to the bowel, diverticulitis, and Crohn’s disease (Kent et al.). Ileostomies are not irrigated because the fecal content of the ileum is liquid and cannot be controlled. Water is inserted into the colostomy, and the water and feces are expelled from the colostomy into the irrigation sleeve and then the toilet. Once the patient has established a routine and has established bowel continence, a small appliance can be worn over the stoma. These “stoma caps” are small-capacity appliances with a pad to soak up discharge and a flatus filter Long-Term Ostomy Care Explain the reason for bowel diversion and the rationale for treatment. Demonstrate self-care behaviors that effectively manage the ostomy. Describe follow-up care and existing support resources. Report where supplies may be obtained in the community. Verbalize related fears and concerns. Demonstrate a positive body image. During the first 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, encourage the patient with an ostomy to avoid foods high in fiber (e.g., foods with skins, seeds, shells), as well as any other foods that cause diarrhea or excessive flatus, such as beans, cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, and simple carbohydrates such as white flour and potatoes. Patients with ileostomies also need to be aware they may experience a tendency to develop food blockages, especially when high-fiber foods are consumed. This is because scar tissue from the place where the intestine passes through the abdominal muscle tightens the inside diameter of the ileum Fiber blockages can cause foul-smelling watery output, abdominal cramping, and distention, along with nausea and vomiting. Foods that commonly cause blockage to occur include popcorn, coconuts, mushrooms, stringy vegetables, and foods with skins and casings (La Laxatives and enemas are dangerous because they may cause severe fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Encourage the intake of dark-green vegetables. These vegetables contain chlorophyll, which helps to deodorize the feces. Buttermilk, cranberry juice, parsley, and yogurt can also prevent odor. Crackers, toast, and yogurt can help to reduce gas, which in turn aids in odor control. CHAP 33: ACTIVITY- 5 SKILLS P 1178 A. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF MOVEMENT NORMAL MOVERMENT AND ALIGNMENT I. Body Alignment or Posture Good posture, or proper body alignment, is the alignment of body parts that permits optimal musculoskeletal balance and operation and promotes healthy physiologic functioning II. Balance A body in correct alignment is balanced. An object is balanced when its center of gravity is close to its base of support, the line of gravity goes through the base of support, and the object has a wide base of support. The center of gravity of an object is the point at which its mass is centered. When the human is standing, the center of gravity is located in the center of the pelvis about midway between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis. The wider the base of support and the lower the center of gravity, the greater the stability of the object will be. B.FACTORS AFFECTING MOVEMENT AND ALLIGNMENT I. Developmental consider II. Physical health 1. Muscular, Skeletal, or Nervous System Problems a. CONGENITAL OR ACQUIRED POSTURAL ABNORMALITIES Postural abnormalities that affect appearance and mobility may be congenital in origin or acquired. Examples of patients experiencing one of these abnormalities include a newborn with developmental hip dysplasia, torticollis (inclining of head to affected side) or a clubfoot; a teenager with lordosis (exaggerated anterior convex curvature of the spine) or scoliosis (lateral curvature of the spine); and an older adult with kyphosis (increased convexity in the curvature of the thoracic spine). b. PROBLEMS WITH BONE FORMATION OR MUSCLE DEVELOPMENT Congenital problems, such as achondroplasia, in which premature bone ossification (bone tissue formation) leads to dwarfism or osteogenesis imperfecta, which is characterized by excessively brittle bones and multiple fractures both at birth and later in life Nutrition-related problems, such as vitamin D deficiency, which results in deformities of the growing skeleton (rickets) Disease-related problems, such as Paget’s disease, in which excessive bone destruction and abnormal regeneration result in skeletal pain, deformities, and pathologic fractures Age-related problems, such as osteoporosis, in which bone destruction exceeds bone formation and in which the resultant thin, porous bones fracture easily The muscular dystrophies are a group of genetically transmitted disorders that share a common progressive degeneration and weakness of skeletal muscles. Myasthenia gravis is a weakness of the skeletal muscles caused by an abnormality at the neuromuscular junction that prevents muscle fibers from contracting. Myotonic muscular dystrophy involves prolonged muscle spasms or stiffening after use. Duchenne muscular dystrophy involves a muscle decrease in size, as well as weakening of muscles over time. c. PROBLEMS AFFECTING JOINT MOBILITY Inflammation, degeneration, and trauma can all interfere with joint mobility. Arthritis is characterized by inflammation, pain, damage to joint The most common type is osteoarthritis, also termed degenerative joint disease. Osteoarthritis is a noninflammatory, progressive disorder of movable joints, particularly weight-bearing joints, characterized by the deterioration of articular cartilage and pain with motion. Trauma to a joint may result in a sprain or a dislocation. A sprain occurs with the wrenching or twisting of a joint, resulting in a partial tear or rupture to its attachments. A dislocation is characterized by the displacement of a bone from a joint with tearing of ligaments, tendons, and capsules D. TRAUMA TO THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM Injury to the musculoskeletal system can result in fractures and soft tissue injuries. A fracture, a break in the continuity of a bone or cartilage, may result from a traumatic injury or some underlying disease process. A strain, the least serious of these injuries, is a stretching of a muscle. E. PROBLEMS AFFECTING THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM A problem in any of the principal parts of the brain or spinal cord involved with skeletal muscle control can affect mobility. The cerebral motor cortex assumes the major role of controlling precise, discrete movements. A cerebrovascular accident (stroke) or head trauma may damage the motor cortex and produce temporary or permanent voluntary motor impairment. Basal ganglia integrate semivoluntary movements such as walking, swimming, and laughing. In Parkinson’s disease, there is progressive degeneration of the basal ganglia of the cerebrum, thus affecting walking and coordination. The pyramidal pathways of the nervous system convey voluntary motor impulses from the brain through the spinal cord by way of two major pathways: (1) the pyramidal pathway and (2) the extrapyramidal pathway. With trauma to the spinal cord, transection (severing) of these motor pathways results in complete bilateral loss of voluntary movement below the level of the trauma. 2. Problems Involving Other Body Systems The pathology of numerous other acute and chronic illnesses may also affect mobility. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and conditions such as ascites (accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity) may alter posture. Any illnesses that interfere with oxygenation at the cellular level decrease the amount of oxygen available to the muscles for work and thus decrease activity tolerance. These illnesses include anemia, angina, cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. III.MENTAL HEALTH IV. LIFESTYLE V.ATTITUDE AND VALUE VI.FATIGUE ANS STRESS C. EXERCISE I.TYPES OF EXERCISE: Exercise can be divided into two major types. One is based on the type of muscle contraction occurring during the exercise. The second is based on the type of body movement occurring and the health benefits achieved. 1. Muscle Contraction Isotonic exercise involves muscle shortening and active movement. Examples include carrying out ADLs, independently performing range-of-motion exercises, and swimming, walking, jogging, and bicycling. Potential benefits include increased muscle mass, tone, and strength; improved joint mobility; increased cardiac and respiratory function; increased circulation; and increased osteoblastic or bonebuilding activity. These benefits do not occur when the nurse or family member performs passive rangeof-motion exercises for a patient because the patient’s muscles do not exert effort. Isometric exercise involves muscle contraction without shortening (i.e., there is no movement or only a minimum shortening of muscle fibers). Examples include contractions of the quadriceps and gluteal muscles, such as what occurs when holding a Yoga pose. Potential benefits are increased muscle mass, tone, and strength; increased circulation to the exercised body part; and increased osteoblastic activity. Isokinetic exercise involves muscle contractions with resistance. The resistance is provided at a constant rate by an external device, which has a capacity for variable resistance. Examples include rehabilitative exercises for knee and elbow injuries and lifting weights. Using the device, the person takes the muscles and joint through a complete range of motion (the maximum degree of movement of which a joint is normally capable) without stopping, meeting resistance at every point. A continuous passive motion (CPM) device used postoperatively after joint surgery (knee replacement, anterior cruciate ligament [ACL] repair) performs these same type exercises 2. Body Movement Types of exercise involving body movement include aerobic exercises, stretching exercises, strength and endurance exercises, and movement and ADLs. Aerobic exercise refers to sustained (often rhythmic) muscle movements that increase blood flow, heart rate, and metabolic demand for oxygen over time, promoting cardiovascular conditioning. Examples of aerobic activities include swimming, walking, jogging, cross-country skiing, aerobic dancing, bicycling, jumping rope, and racquetball. Low-impact aerobic exercises include those activities in which at least one foot is on the ground at all times, like walking, rowing, or riding a stationary bicycle. High-impact exercises include activities that are more apt to jar the spine, like running, jumping, or kick-boxing. Stretching exercises involve movements that allow muscles and joints to be stretched gently through their full range of motion, increasing flexibility. Specific warm-up and cool-down exercises, Hatha yoga, and some forms of dance are examples. Strength and endurance exercises are components of a variety of muscle-building programs. Weight training, calisthenics, and specific isometric exercises can build both strength and endurance, increasing the power of the musculoskeletal system, and generally improving the whole body. Movement and ADLs include housecleaning, running after playful toddlers, climbing stairs instead of riding in elevators, and so on. Household activities can also contribute to an active lifestyle. II.EFFECT OF EXERCISE ON MAJOR BODY SYSTEM III. RISK RELATED TO EXERCISE IV.EFFECT OF IMMOBILITY ON THE BODY (***) 1. Cardiovascular System The primary and serious effects of immobility on the cardiovascular system include increased cardiac workload, orthostatic hypotension, and venous stasis, with resulting venous thrombosis. Immobility results in an increased workload for the heart. With immobility, the skeletal muscles that normally compress valves in the leg veins and help to pump the blood back to the right side of the heart do not adequately contract. There is less resistance offered by the blood vessels and blood pools in the veins, thus increasing the venous blood pressure and changing the distribution of blood in the immobile person. As a result, the heart rate, cardiac output, and stroke volume increase. Immobility predisposes the patient to thrombi formation because of venous stasis, especially in the legs, where normal muscular activity helps move blood toward the central circulatory system. During periods of immobility, calcium leaves the bones and enters the blood, where it influences blood coagulation, leading to an increased risk of thrombus formation. A person who is immobile is more susceptible to developing orthostatic hypotension. The normal neurovascular adjustments that occur to maintain systemic blood pressure with position changes are not used during periods of inactivity and become inoperative. A drop in blood pressure may occur as a result of a lack of vasoconstriction when changing from a supine to an upright position. The person tends to feel weak and faint when this condition occurs. 2. Respiratory System The effects of immobility on the respiratory system are related to decreased ventilatory effort and increased respiratory secretions. Immobility causes a decrease in the depth and rate of respirations, in part because of a reduced need for oxygen by body cells. When areas of lung tissue are not used over time, atelectasis (incomplete expansion or collapse of lung tissue) may occur. Immobility results in a poor exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen, upsets their balance in the body, and eventually causes an acid–base imbalance. When a person is immobile, the movement of secretions in the respiratory tract is decreased, causing secretions to pool and leading to respiratory congestion. These conditions predispose the person to respiratory tract infections. Hypostatic pneumonia is a type of pneumonia that results from inactivity and immobility. The situation worsens when the person is dehydrated or using pharmacologic agents that increase the tenacity of secretions, depress the coughing mechanism, and/or depress respirations. Decreased movement in the thoracic cage during respirations also occurs with immobility. This decrease may be due to loss of tonus in muscles involved with respirations, pressure on the chest wall because of the patient’s position in bed, or depression of the respiratory system by various pharmaceutical agents. 3. Musculoskeletal System 4. Metabolic Processes Because the resting body requires less energy, the cellular demand for oxygen is decreased, leading to a 5. Immobility (musculoskeletal disuse) leads to decreased muscle size (atrophy), tone, and strength; decreased joint mobility and flexibility; bone demineralization; and limited endurance, resulting in problems with ADLs. Immobility is often the cause of contractures and ankylosis, a consolidation and immobilization of a joint. Contractures result from atrophy of muscles and from a decrease in the muscle’s strength, coordination, and endurance, resulting in an inability to function. A joint can be permanently fixed when ankylosed. The process of bone demineralization (osteoporosis) is also increased in immobile patients. Normally, the stress and strain of weight-bearing activity stimulate bone formation and balance it with the natural destruction of bone. With immobility, however, bone formation slows while breakdown increases, resulting in a net loss of bone calcium, phosphorus, and bone matrix. This condition, disuse osteoporosis, is characterized by bones that may be either spongy or brittle. decreased metabolic rate. In many immobilized patients, however, factors such as fever, trauma, chronic illness, or poor nutrition can actually increase the body’s metabolic demands and increase catabolism (the breakdown of the body’s protein stores to provide energy to meet the body’s energy requirements). If unchecked, this process results in muscle wasting and a negative nitrogen balance. Anorexia, or decreased appetite, often accompanies and compounds this problem. Gastrointestinal System Immobility leads to disturbances in appetite, decreased food intake, altered protein metabolism, and poor digestion and utilization of food. results in constipation, poor defecation reflexes, and an inability to expel feces and gas adequately. 6. Urinary System Urinary stasis favors the growth of bacteria that, when present in sufficient quantities, may cause urinary tract infections. Poor perineal hygiene, incontinence, decreased fluid intake, or an indwelling urinary catheter can increase the risk for urinary tract infection in an immobile patient. Immobility also predisposes the patient to renal calculi, or kidney stones, which are a consequence of high levels of urinary calcium; urinary retention and incontinence resulting from decreased bladder muscle tone; the formation of alkaline urine, which facilitates growth of urinary bacteria; and decreased urine volume. 7. Skin: the impaired circulation that accompanies immobility may result in serious skin breakdown. 8. Psychosocial Outlook D. NURSING PROCESS FOR ACTIVITY I.ASSESSMENT 1.Nursing history 2.Physical assessment a. Ease of movement and gait (tremor,tics,gait) b.Alignment c. Join structure and function d.Muscle mass, tone and strength Hypertrophy refers to increased muscle mass resulting from exercise or training. Atrophy describes muscle mass that is decreased through disuse or neurologic impairment Decreased tone, also known as hypotonicity or flaccidity, results from disuse or neurologic impairments and is described as a weakness of the involved area. Spasticity or hypertonicity, increased tone that interferes with movement, is also caused by neurologic impairments and is often described as a stiffness, tightness, or pulling of the muscle. Impaired muscle strength or weakness is termed paresis. The absence of strength secondary to nervous impairment is called paralysis. Hemiparesis refers to weakness of one half of the body, and hemiplegia is paralysis of one half of the body. Paraplegia is paralysis of the legs, and quadriplegia is paralysis of the arms and legs. e.Endurance II.DIAGNOSIS III.PLANNING IV. IMPLEMENT 1. Application of Ergonomics to Prevent Injury Ergonomics includes proper body movement in daily activities, the prevention and correction of problems associated with posture, and the enhancement of coordination and endurance. Techniques to prevent back stress that should be included routinely in injury-prevention programs include Develop a habit of erect posture (correct alignment). Slouching can strain neck and back muscles. When sitting, use the chair back to support the whole spine, keeping shoulders back but relaxed. Use the longest and the strongest muscles of the arms and the legs to help provide the power needed in strenuous activities. Use the internal girdle and a long midriff to stabilize the pelvis and to protect the abdominal viscera when stooping, reaching, lifting, or pulling. Work as closely as possible to an object that is to be lifted or moved. Face the direction of your movement. Avoid twisting your body. Use the weight of the body as a force for pulling or pushing, by rocking on the feet or leaning forward or backward. Slide, roll, push, or pull an object, rather than lift it, to reduce the energy needed to lift the weight against the pull of gravity.Use the weight of the body to push an object by falling or rocking forward and to pull an object by falling or rocking backward.Push rather than pull equipment when possible. Keep arms close to your body and push with your whole body, not just your arms. Begin activities by broadening your base of support. Spread the feet to shoulder width.Make sure that the surface is dry and smooth when moving an object to decrease the effects of friction. Rough, wet, or soiled surfaces can contribute to increased friction, increasing the amount of effort required to move an object.Flex the knees, put on the internal girdle, and come down close to an object that is to be lifted.Break up heavy loads into smaller loads. Take breaks from lifting or moving to relax and recover. 2. Ensuring Safe Patient Handling and Movement (***): Safe patient handling and transfers involve the use of patient assessment criteria, algorithms for patient handling decisions, and proper use of patient handling equipment. a. SAFE PATIENT TRANSFER Assess the patient. Know the patient’s medical diagnosis, capabilities, and any movement not allowed. Apply braces or any device the patient wears before helping from bed. Assess the patient’s ability to assist with the planned movement. Encourage patients to assist in their own transfers. Encouraging patients to perform tasks that are within their capabilities promotes independence. It is important to eliminate or reduce unnecessary tasks to reduce the risk of injury and increase the patient’s self-esteem and mobility levels. Assess the patient’s ability to understand instructions and cooperate with the staff to achieve the movement. Patient cooperation during handling and movement is an important factor in preventing adverse events b. EQUIPMENT AND ASSISTIVE DEVICES Gait Belts A gait belt is a device used for transferring patients and assisting with ambulation (Fig. 33-10 on page 1155). The belt, which often has handles, is placed around the patient’s waist and secured by Velcro fasteners. The gait belt is used to help the patient stand and provides stabilization during pivoting. Gait belts also allow the nurse to assist in ambulating patients who have leg strength, can cooperate, and require minimal assistance. Do not use gait belts on patients with abdominal or thoracic incisions. Stand-Assist and Repositioning Aids Many types of devices can help a patient to stand. These devices can be freestanding or attached to the bed or wheelchair. Lateral-Assist Devices Lateral-assist devices reduce patient–surface friction during side-to-side transfers. Roller boards, slide boards, transfer boards, inflatable mattresses, and friction-reducing lateral-assist devices are examples example is a transfer board, usually made of smooth, rigid, low-friction material (such as coated wood or plastic). The board, which is placed under the patient, provides a slick surface for the patient during transfers, reducing friction and the force required to move the patient. Friction-Reducing Sheets: Friction-reducing sheets can be used under patients to prevent skin shearing when moving patients in bed and when assisting with lateral transfers. Their use reduces friction and the force required to move patients. Mechanical Lateral-Assist Devices: Mechanical lateral-assist devices include specialized stretchers and eliminate the need to slide the patient manually. portion of the device moves from the stretcher to the bed, sliding under the patient, bridging the bed and stretcher (Fig. 33-12). The device is then returned to the stretcher, effectively moving the patient without any pulling by staff members. Transfer Chairs: Chairs that can convert into stretchers are available. These are useful with patients who have no weight-bearing capacity, cannot follow directions, and/or cannot cooperate. The back of the chair bends back, and the leg supports elevate to form a stretcher configuration, eliminating the need for lifting the patient. Powered Stand-Assist and Repositioning Lifts: These devices can be used with patients who can bear weight on at least one leg, can follow directions, and are cooperative. A simple sling is placed around the patient’s back and under the arms. Some devices come with breathable slings that can remain under the patient, reducing the risk for the nurse in turning the patient to position the sling. The patient rests the feet on the device’s footrest and places the hands on the handle. The device mechanically assists the patient to stand, without any assistance from the nurse Powered Full-Body Lifts: These devices are used with patients who cannot bear any weight to move them out of bed, into and out of a chair, and to a commode or stretcher. A full-body sling is placed under the patient’s body, including head and torso, then the sling is attached to the lift 3. Positioning patients in bed (***): a. COMMON DEVICES TO PROMOTE CORRECT ALIGNMENT Foam Wedges and Pillows:Foam wedges and pillows are used primarily to provide support or to elevate a body part. MattressesA mattress must be firm but have sufficient “give” to permit proper body alignment, as well as to be comfortable and supportive. Adjustable BedsThe nurse can elevate the head and/or foot of an adjustable bed to the desired degree. Position the bed at the height that will let the patient stand with the least amount of effort. Health care workers use the higher bed positions so that they do not strain their backs while providing bed care. Trapeze BarA trapeze bar (Fig. 33-15) is a handgrip suspended from a frame near the head of the bed. A patient can grasp the bar with one or both hands and raise one’s trunk from the bed. Additional Equipment The greatest danger to the feet occurs when they are unsupported in the dorsiflexion position. The toes drop downward, and the feet are in plantar flexion If maintained for extended periods, plantar flexion can cause an alteration in the length of muscles, and the patient may develop a complication called footdrop. In this position, the foot is unable to maintain itself in the perpendicular position, heel–toe gait is impossible, and the patient experiences extreme difficulty in walking. The use of a foot support, such as a foot board, foot boot, or high-top sneakers, helps avoid this complication. If top bedding must be kept off the patient’s lower extremities, a device called a cradle is used. A cradle is usually a metal frame that supports the bed linens away from the patient while providing privacy and warmth If a patient is paralyzed or unconscious, hand–wrist splints or hand rolls may be necessary to provide a means for keeping the thumb in the correct position, b. PROTECTIVE POSITIONING (***)- TABLE 33.6 Fowler’s Position The semi-sitting position, or Fowler’s position, calls for the head of the bed to be elevated 45 to 60 degrees. This position is often used to promote cardiac and respiratory functioning because abdominal organs drop in this position, providing maximal space in the thoracic cavity. This is also the position of choice for eating, conversation, and urinary and intestinal elimination. In the high-Fowler’s position, the head of the bed is elevated 90 degrees. When a bedside table with a pillow on top of it is placed in front of the patient in high-Fowler’s position, the patient can lean forward and rest the arms on the pillow, assuming a posture that allows for maximal lung expansion. In lowFowler’s or semi-Fowler’s position, the head of the bed is elevated only 30 degrees. In Fowler’s position, the buttocks bear the main weight of the body. In this position, the heels, sacrum, and scapulae are at risk for skin breakdown and require frequent assessment Supine or Dorsal Recumbent Position: In the supine position, the patient lies flat on the back with the head and shoulders slightly elevated with a pillow unless contraindicated, such as spinal anesthesia or surgery on the spinal vertebrae. Side-Lying or Lateral Position In the side-lying position, the patient lies on the side and the main weight of the body is borne by the lateral aspect of the lower scapula and the lateral aspect of the lower ilium. Although it relieves pressure on the scapulae, sacrum, and heels and allows the legs and feet to be comfortably flexed, support pillows are needed for correct positioning (see Table 33-6). The oblique position, a variation of the side-lying position, is recommended as an alternative to the sidelying position because it places significantly less pressure on the trochanter region. The patient turns toward the side with the hip of the top leg flexed at a 30-degree angle and the knee flexed at 35 degrees. The calf of the upper leg is positioned slightly behind the body’s midline. Pillows support Another variation of the lateral position is Sims’ position. In this position, the patient again lies on the side, but the lower arm is behind the patient and the upper arm is flexed at both the shoulder and the elbow. In this position, the main body weight is borne by the anterior aspects of the humerus, clavicle, and ilium Prone Position In the prone position, the person lies on the abdomen with the head turned to the side. The body is straight in the prone position because the shoulders, head, and neck are in an erect position, the arms are easily placed in correct alignment with the shoulder girdle, the hips are extended, and the knees can be prevented from flexing or hyperextending. When patients on bed rest use this position periodically, it helps to prevent flexion contractures of the hips and knees. However, the pull of gravity on the trunk when the patient lies prone produces a marked lordosis or forward curvature of the lumbar spine. The position is thus contraindicated for people with spinal problems. 4. Using Graduated Compression Stockings and Pneumatic Compression Devices Venous stasis and the development of venous thrombosis are potential complications of immobility. Graduated compression stockings and pneumatic compression devices are passive interventions prescribed to aid in the prevention of these complications. Graduated compression stockings are often used for patients at risk for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Be prepared to apply the stockings in the morning before the patient is out of bed and while the patient is supine. Do not massage the legs. If a clot is present, it may break away from the vessel wall and circulate in the bloodstream.Check the legs regularly for redness, blistering, swelling, and pain. Some recommend checking the legs at least once every 8 hours; 5. Turning the Patient in Bed (skill 33.2) 6. Moving a Patient Up in Bed (skill 33.3) The first decision point is whether the patient can assist. If the patient is fully able, caregiver assistance is not needed 7. Moving a Patient from Bed to Stretcher (skill 33.4) 8. Moving a Patient from Bed to Chair (skill 33.5) 9. Helping Patients Ambulate(***) A. PHYSICAL CONDITIONING TO PREPARE FOR AMBULATION -Quadriceps and Gluteal Setting Drills (Sets) Quadriceps drills are an isometric exercise—an exercise in which muscle tension occurs without a significant change in the length of the muscle. One of the most important muscle groups used in walking is the quadriceps femoris. This muscle group helps extend the leg and flex the thigh. To help reduce weakness and make first attempts at walking easier, encourage bedridden patients to contract this muscle group frequently Have the patient contract or tighten the muscles on the front of the thighs. The patient has the feeling of pushing the knees downward into the mattress and pulling the feet upward. Have the patient hold the position just described while counting slowly to four and then relax the muscles for an equal count. Emphasize that relaxation is important to prevent muscle fatigue. Caution the patient not to hold the breath during these exercises to avoid straining the heart. Teach the patient to do quadriceps drills two or three times each hour, four to six times a day, or as ordered by the health care provider. Instruct the patient to stop the exercise short of muscle fatigue. The muscles in the buttocks can be exercised in the same way by pinching the buttocks together and then relaxing them. This is called gluteal setting. Tightening and holding the abdominal muscles for 6 seconds and then relaxing them - Pushups The muscles of the arms and shoulders may also need strengthening before the patient is ready to be out of bed. A trapeze attached to the bed of a patient who has limited use of the lower part of the body helps the patient to move about in bed and strengthens muscles in the upper part of the body. -Dangling Dangling refers to the position in which the person sits on the edge of the bed with legs and feet over the side of the bed. Place the patient in the sitting position in bed for a few minutes. This will accustom the patient to this position and help prevent feelings of faintness. Place the bed in the low position or have a footstool handy, on which the patient can rest the feet while dangling. Move the patient toward the side of the bed near you so that you do not stretch and strain while turning the patient. Pivot the patient a quarter of a turn by supporting the shoulders and legs. Swing the patient’s legs over the side of the bed. The patient may place hands on your shoulders. Rest the patient’s feet on the floor or on a footstool. This gives a sense of security and lessens the likelihood that the patient will slide off the bed. Have the patient move the feet using an up-and-down, marching motion. This promotes circulation in the legs. Assess for lightheadedness or other signs of orthostatic hypotension (dizziness, nausea, tachycardia, or pallor). Remain with the patient and be ready to place the patient back to a lying position if feeling faint, to prevent falling out of bed. B. PROVIDING ASSISTANCE WITH WALKING Before getting the patient out of bed, do the following: Assess the patient’s ability to walk and the need for assistance (one nurse or two nurses, walker, cane, walking belt, or crutches). Explain to the patient exactly what is to be done: transfer technique from bed to erect position, projected distance to be ambulated, assistance available, and the correct manner of using it. Instruct the patient to alert the nurse immediately if feeling dizzy or weak. Ensure that the patient has a clear path for ambulation. Provide skid-proof footwear. C.ONE-NURSE ASSIST D. TWO NURSE ASSIST E. MECHANICAL AIDS FOR WALKING: The most common are walkers, canes, braces, and crutches. -Walker A walker is a lightweight metal frame (usually aluminum) with four legs (see Fig. 33-23A). Walkers improve balance by increasing the patient’s base of support, enhancing lateral stability, and supporting the patient’s weight. These walkers are best for patients with a gait that is too fast for a walker without wheels and for patients who have difficulty lifting a walker. Wheeled walkers are best for patients who need minimal weight bearing from the walker. When the patient’s hands are placed on the grips, elbows should be flexed about 30 degrees Instruct a patient using a walker to do the following: Wear nonskid shoes or slippers. When rising from a seated position, use the chair arms for support. Once standing, place one hand at a time on the walker and move forward into it. Begin by pushing the walker forward, keeping the back upright. Place one leg inside the walker, keeping the walker in place. Then, step forward with the remaining leg into the walker, keeping the walker still. Repeat the process by moving the walker forward again. Caution the patient to avoid pushing the walker out too far in front and leaning over it. Patients should always step into the walker, rather than walking behind it, staying upright as they move (Mayo Clinic, n.d.a). Never attempt to use a walker on stairs. -Canes: Canes widen a person’s base of support, providing improved balance. When walking with a cane, instruct patients to hold the cane in the hand opposite the side that needs support Ambulation proceeds in the following fashion: 1. The patient stands with weight evenly distributed between the feet and the cane. 2. The cane is held on the patient’s stronger side and is advanced one small stride ahead (AAOS, 2015). 3. Supporting weight on the stronger leg and the cane, the patient advances the weaker foot forward, parallel with the cane. 4. Supporting weight on the weaker leg and the cane, the patient brings the stronger leg forward to finish the step -Braces: Braces that support weakened leg muscles are available in many variations. Nursing responsibilities include knowing when the brace is to be worn and the correct technique for applying the brace, monitoring to ensure correct use of the brace by the patient, and observing for any untoward problems the brace might cause (e.g., skin irritation -Crutches Sometimes it is necessary for patients to use crutches for a time to avoid using one leg or to help strengthen one or both legs. The two types of crutches most commonly used are axillary crutches and forearm crutches (Fig. 33-24 on page 1170). Forearm crutches are used for patients requiring long-term support for ambulation (Mincer, 2007). A supportive frame extends beyond the handgrip for the lower arm to help guide the crutch. These crutches are more likely to be used by patients who have permanent limitations and will always need crutch assistance for ambulation. Axillary crutches are used to provide support for patients who have temporary restrictions on ambulation. CHAP 31: HYGIENE- 5SKIL P1016 Hygiene measure-all needs, environmental care, chapter skill A.HYGIENE PRACTICE Hygienic practices include caring for the skin, hair, nails, eyes, ears, nose, mouth, feet, and perineal area The skin, or integument, is the largest organ of the body and has multiple functions. The integumentary system is made up of the skin, the subcutaneous layer directly under the skin, and the appendages of the skin, including the hair and nails. Adequate skin hygiene, including foot care, contributes to maintaining skin condition and integrity, an important first line of defense, preventing the entry of pathogens, minimizing absorption of harmful substances, and preventing excessive water loss .Hair is an accessory structure of the skin. Illness affects the hair, especially when endocrine abnormalities, increased body temperature, poor nutrition, or anxiety and worry are present. Changes in the color or condition of the hair shaft are related to changes in hormonal activity or to changes in the blood supply to hair follicles. The nails are an accessory structure of the skin composed of epithelial tissue. Healthy nail beds are pink, convex, and evenly curved A person’s general health influences the health of that person’s mouth and teeth, and proper care of the mouth and teeth lends to overall health. There is an established relationship between healthy teeth and a diet sufficient in calcium and phosphorus, along with vitamin D, The perineal area is dark, warm, and often moist, providing conditions that favor bacterial growth B.FACTORS AFFECT PERSONAL HYGIENE 1. Culture 2.Socioeconomic class 3. Spiritual practices 4.Developmental level 5. Health sate C.NURSING PROCESS FOR HYGIENE I.ASSESSMENT The major cause of tooth loss in adults older than 35 years of age is gum disease. Gingivitis is an inflammation of the gingiva, the tissue that surrounds the teeth. Periodontitis, or periodontal disease, is a marked inflammation of the gums that also involves degeneration of the dental periosteum (tissues) and bone. Symptoms include bleeding gums; swollen, red, painful gum tissues; receding gum lines with the formation of pockets between the teeth and gums; pus that appears when gums are pressed; and loose teeth. If unchecked, plaque builds up and, along with dead bacteria, forms hard deposits called tartar at the gum lines. Stomatitis, an inflammation of the oral mucosa, has numerous causes, such as bacteria, virus, mechanical trauma, irritants, nutritional deficiencies, and systemic infection. Symptoms may include heat, pain, increased flow of saliva, and halitosis. Glossitis, an inflammation of the tongue, can be caused by deficiencies of vitamin B12, folic acid, and iron. Cheilosis, an ulceration and dry scaling of the lips with fissures at the angles of the mouth, is most often caused by vitamin B complex deficiencies (especially riboflavin). Dry oral mucosa may simply be related to dehydration or may be caused by mouth breathing, an alteration in salivary functioning, or certain medications (e.g., anticholinergic drugs). Oral malignancies, appearing as lumps or ulcers, must be distinguished from benign mouth problems because early detection may lead to cure; later detection can lead to radical surgery or death. Teach patients to see their dentist immediately if they notice white or red patches, persistent sores, swelling, bleeding, numbness, or pain in the mouth. Dandruff: Dandruff is a condition characterized by itching and flaking of the scalp and may be complicated by the embarrassment it causes. Hair loss becomes a potential problem only when it exceeds hair growth. Absence or loss of hair is called alopecia. Pediculosis Infestation with lice is called pediculosis. There are three common types of lice: Pediculus humanus capitis, which infests the hair and scalp; Pediculus humanus corporis, which infests the body; and Phthirus pubis, which infests the shorter hairs on the body, usually the pubic and axillary hair. Lice lay eggs, called nits, on the hair shafts. Nits are white or light gray and look like dandruff but cannot be brushed or shaken off the hair. Frequent scratching and scratch marks on the body and the scalp suggest the presence of pediculosis. Pediculosis can be spread directly by contact with the hair of infested people. Ticks Ticks are an important problem because they can transmit serious diseases such as Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Colorado tick fever. Ticks attach themselves to a human host as the person brushes past leaves, brush, and tall grasses. Once on a person, ticks move to a warm and moist location, like the hairline, armpit, or groin, where they burrow into the host’s skin and feed off the host’s blood. Transmission of tick-borne diseases can be decreased if the tick is removed within 24 hours of becoming attached. To remove a tick, grasp it with clean tweezers close to the skin. Pull upward with steady, even pressure (CDC, 2015). Once the tick is removed, cleanse the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol, an iodine scrub, or soap and water (CDC). A person should seek medical attention if a rash or fever develops within several weeks of removing a tick. The most important thing to consider regarding ticks is that prevention of tick bites is key. Wearing long sleeves, long pants, and long socks can help prevent ticks from coming in contact with the skin. Apply insect repellant on clothing (permethrin) and exposed skin II. IMPLEMENTING The following sections discuss hygiene measures, including providing scheduled care; assisting with bathing and skin care; massaging; providing routine head-to-toe hygiene care; providing environmental care, including making the bed; and teaching patients about skin care. 1.Providing Scheduled Hygiene Care When patients require nursing assistance with personal hygiene, provide this care at regular intervals. In most hospitals and long-term care settings, early morning care, morning care, afternoon care, hour of sleep care, and care as needed are provided. EARLY MORNING CARE Shortly after the patient awakens, assist with toileting if necessary and then provide comfort measures to refresh the patient and prepare him or her for breakfast (or diagnostic tests, procedures, or therapies). Nursing measures include washing the face and hands and providing mouth care. MORNING CARE (AM CARE) After breakfast, complete morning care. Depending on the patient’s self-care abilities, offer assistance with toileting, oral care, bathing, back massage, special skin care measures (e.g., pressure injury), hair care (includes shaving if indicated), cosmetics, dressing, and positioning for comfort. Morning care is often categorized as self-care, partial care, or complete care. . Patients identified as partial care most often receive morning hygiene care at the bedside or seated near the sink in the bathroom. They usually require assistance with body areas that are difficult to reach. Patients identified as complete care require nursing assistance with all aspects of personal hygiene. A complete bed bath is done, or the patient is taken to the shower. AFTERNOON CARE (PM CARE) Hospitalized patients frequently receive visitors in the afternoon or evening or use this time to rest when not scheduled for tests or therapies. Ensure the patient’s comfort after lunch and offer assistance to nonambulatory patients with toileting, hand washing, and oral care. HOUR OF SLEEP CARE (HS CARE) Shortly before the patient retires, again offer assistance with toileting, washing of the face and hands, and oral care. Because many patients find that a back massage helps them to relax and fall asleep, it may be appropriate to offer one. Change any soiled bed linens or clothing, and position the patient comfortably. Ensure that the call light and any other objects the patient desires (e.g., urinal, radio, water glass) are within easy reach. AS NEEDED CARE (PRN CARE) In addition to scheduled care, offer individual hygiene measures as needed. Some patients require oral care every 2 hours. Patients who are diaphoretic (sweating profusely) may need their clothing and bed linens changed several times a shift. 2. Assisting With Bathing and Skin Care The simple act of bathing a patient is a vital and caring intervention. Nurses whose primary focus is the patient, however, can use the time spent on assisting with bathing to establish a rapport with the patient and to further assess the patient’s integumentary system. Bathing is performed in a matter-of-fact and dignified manner. SHOWER AND TUB BATHS A shower may be the preferred method of bathing for patients who are ambulatory and able to tolerate the activity. Tub baths may be an option, particularly in long-term care or other community-based settings, depending on facility policy. Provide a place for a weak or physically disabled patient to sit in a shower. Some nurses have reported that a commode chair with the pan removed serves effectively as a shower chair and offers the patient more support than a stool or chair. Check to see that the water temperature is safe and comfortable—100°F to less than 120° to 125°F Have the patient grasp the handrails at the side of the tub, or place a chair at the side of the tub. The patient sits on the chair and eases to the edge of the tub. After putting both feet into the tub, it is then relatively easy for the patient to reach the opposite side and ease down into the tub. The patient may kneel first in the tub and then sit in it; this process can be reversed when leaving the tub. Use a hydraulic lift, when available, to lower and lift patients who are unable to maneuver safely or completely bear their weight. Some community-based settings have walk-in tubs available. For example, if the patient is confused and becomes agitated as a result of overstimulation when bathing, reduce the stimuli. Turn down the lights and play soft music and/or warm the room before taking the patient into it BED BATH Implement the following nursing measures to help patients take a bath in bed: Provide the patient with articles for bathing. If using a basin of water for bathing, ensure the water is a comfortable and safe temperature. Place these items conveniently for the patient on a bedside stand or overbed table. Provide privacy for the patient. Make sure the call device is within reach. Place cosmetics in a convenient place for the patient. Provide a mirror, a good light, and hot water for patients who wish to shave with a razor. Assist patients who cannot bathe themselves completely. For example, some patients can wash only the upper parts of the body. Nursing personnel then complete the remainder of the bath. THE DISPOSABLE BATH The use of disposable bath products is an alternative to the traditional use of soap and water. Disposable bath products are prepackaged in single-use units, heated before use, and do not require rinsing PROMOTING SKIN HEALTH An easy and effective way to promote the barrier function of the skin and keep the skin healthy is the daily use of soap substitutes, topical moisturizers and emollients, and barrier products. The use of mild cleansers with pH close to skin pH is recommended The use of chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) for bathing has been shown to reduce colonization of skin with pathogens and is an important measure utilized by institutions in an attempt to decrease health care–associated infections (HAIs) Topical emollient agents—also known as moisturizers—can be applied to the skin as a lotion, cream, gel, or ointment. They act to seal water into the skin and replace lipids in the skin, effectively hydrating the skin and recreating its waterproof barrier. Apply topical moisturizers after bathing. Ideally, they should be applied twice a day but may need more frequent application, depending on the skin condition and the product used. Skin barrier products include creams, ointments, and films. These products are used to protect vulnerable skin and to protect skin at risk for damage caused by excessive exposure to water and irritants, such as urine and feces. They are also used to prevent skin breakdown around stomas and wounds with excessive exudate. Application of one of these products forms a thin layer on the surface of the skin to repel potential irritants. Bariatrics is the science of providing health care for those who have extreme obesity, taking both a patient’s weight and the distribution of this weight throughout the body into consideration. Patients with bariatric needs are at increased risk of skin breakdown and therefore require focused nursing care to prevent skin issues (Cowdell & Radley, 2014). Assess the skin of bariatric inpatients twice a day, lifting and separating folds of skin to assess the area, utilizing extra help as necessary (Black & Hotaling, 2015). Nonsoap cleansers should be used and the skin should be dried to prevent retained moisture PROVIDING PERINEAL CARE Perineal cleaning should be performed in a matter-of-fact and dignified manner If the patient has an indwelling catheter and the facility recommends daily care for the catheter, this is usually done after perineal care Patients with urinary or fecal incontinence are at risk for perineal skin damage. This damage is related to moisture, changes in the pH of the skin, overgrowth of bacteria and infection of the skin, and erosion of perineal skin from friction on moist skin. Skin care for these patients should include measures to reduce overhydration (excess exposure to moisture), contact with ammonia and bacteria, and friction. Remove soil and irritants from the skin during routine hygiene, and clean the area when the skin becomes exposed to irritants. Avoid using soap and excessive force for cleaning. The use of perineal skin cleansers, moisturizers, and barriers is recommended for skin care for the incontinent patient. Providing Vaginal Care Vaginal mucous secretions are odor free until they combine with air and perspiration. Thus, for vaginal care, using plain soap and water is the most effective means to control odor. PROVIDING PERINEAL CARE Perineal care may be carried out while the patient remains in bed female patient, spread the labia and move the washcloth from the pubic area toward the anal area to prevent carrying organisms from the anal area back over the genital area (Figure A). Always proceed from the least contaminated area to the most contaminated area. For a male patient, clean the tip of the penis first, moving the washcloth in a circular motion from the meatus outward (Figure B). Wash the shaft of the penis using downward strokes toward the pubic area (Figure C). Always proceed from the least contaminated area to the most contaminated area. Rinse the washed areas well with plain water. In an uncircumcised male patient (teenage or older), retract the foreskin (prepuce) while washing the penis. Pull the uncircumcised male patient’s foreskin back into place over the glans penis to prevent constriction of the penis, which may result in edema and tissue injury. It is not recommended to retract the foreskin for cleaning during infancy and childhood, as injury and scarring could occur Dry the cleaned areas and apply an emollient as indicated. Avoid the use of powder. Powder may become a medium for the growth of bacteria. Turn the patient on his or her side and continue with cleansing the anal area. MASSAGING THE BACK A backrub acts as a general body conditioner and can relieve muscle tension and promote relaxation. A backrub improves circulation; can decrease pain, distress, and anxiety; can improve sleep quality; and provides a means of communication with the patient through the use of touch. Be aware of the patient’s medical diagnosis when considering giving a backrub. A backrub is contraindicated, for example, if the patient has had back surgery or has fractured ribs. 3. Providing Care for Body Piercing Basic wound care used for body piercings is usually called “aftercare.” Aftercare techniques are used for the new piercing and whenever the piercing fistula has become disrupted through injury or exhibits signs of infection or inflammation Piercing jewelry may cause difficulty with placement of treatment devices, and can interfere with diagnostic imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized axial tomography (CT scan), or contribute to patient injury during MRI or other procedures, such as surgery or Foley catheter placement PROVIDING BODY PIERCING CARE Perform hand hygiene before providing care. Explain what you are going to do. Put on gloves. Clean the jewelry and the piercing site of all crust and debris. Rinse the site with warm water and use a cotton swab to gently remove any crusting. Rinse well. Remove gloves. Perform hand hygiene. Advise patients to avoid the use of alcohol, peroxide, and ointments at the site. Oral piercing aftercare includes rinsing with an antibacterial, alcohol-free mouthwash for 30 to 60 seconds after meals and at bedtime. The patient should brush the teeth with a new, soft-bristled toothbrush. Advise patients to avoid oral tobacco use. Most piercings take 6 to 8 weeks to heal, TOOTH BRUSHING AND FLOSSING Brush and floss teeth twice a day and rinse the mouth after meals. A soft-bristled toothbrush should be small enough to reach all teeth. Clean and dry all brushes between uses. Bacteria do most damage directly after eating, so make sure the patient brushes the teeth immediately after eating or drinking. In addition, clean the tongue with the toothbrush. Use a toothbrush even when the patient has no or few teeth. It is the only effective way to remove plaque and debris. The toothbrush cannot reach areas between the teeth where food lodges and plaque (a thin film of bacteria that forms on teeth) can build up, so flossing at least once a day is recommended (American Dental Association [ADA], 2016a). Flossing removes the debris that the toothbrush cannot and helps to break up colonies of bacteria. Salt and sodium bicarbonate are far less expensive than proprietary products on the market and just as effective for short-term use. However, these products lack fluoride and should not be used exclusively. MOUTHWASHES Therapeutic mouth rinses that reduce bacteria can help reduce plaque, gingivitis, tartar (hardened plaque) and also freshen breath. Anticavity rinses with fluoride help protect tooth enamel to help prevent or control tooth decay (ADA, n.d.a.). Halitosis, an offensive breath odor, is often systemic in nature. For example, the odor of onions and garlic on the breath comes from the lungs, where the oils are being removed from the bloodstream and eliminated with respiration. DENTURE CARE Failing to wear dentures for a long period allows the gum line to change, thus affecting the fit of the dentures. It is not recommended, however, that dentures be worn continuously (24 hr/day) in order to reduce or minimize denture stomatitis (irritation of the oral tissues) Dentures should be cleaned daily to reduce plaque and potentially harmful microorganisms (Felton et al., 2011). Daily cleaning includes soaking in and brushing with a nonabrasive denture cleanser (Felton et al.). When cleaning dentures, put on gloves and hold them over a basin of water or a sink lined with a washcloth or soft towel (Fig. 31-3) so that if they slip from your grasp, they will not fall onto a hard surface and break. If necessary, grasp the dentures with a 4” × 4” piece of gauze to help prevent them from slipping out of your gloved hands. Use cool or lukewarm water to cleanse them. Hot water may warp the plastic material of which most dentures are made. Use a soft toothbrush and dental cleanser. Do not use toothpaste as it can be too harsh for denture surfaces Providing Eye Care Normally, the eyes are kept clean with lacrimal secretions. During illness, the eyes may produce more secretions than normal and may appear glass-like. Never use soap to clean the eyes because soap is irritating to eye tissues. Dampen a cleaning cloth with the solution of choice and wipe once while moving from the inner canthus to the outer canthus of the eye. This technique minimizes the risk for forcing debris into the area drained by the nasolacrimal duct. If the eyelashes are matted with secretions or debris that cannot be removed by wiping, apply a warm, wet compress to the closed eye for 3 to 5 minutes to loosen the secretions so that they may be removed in a painless manner CARE OF THE UNCONSCIOUS PATIENT’S EYES Patients with diminished or absent blink (corneal) reflexes and patients whose eyelids remain open require frequent eye care, at least every 4 hours. If the eye is not kept moist, corneal ulceration may result from excessive drying of the eye. Nursing measures include using saline or artificial tears, EYEGLASS CARE Encourage patients who need glasses to wear them to avoid eyestrain. Many eyeglasses have plastic lenses, which are considerably lighter in weight than glass lenses but correct vision just as well. Plastic lenses scratch easily. Whenever setting down glasses, make sure they are placed with the lenses up. Clean eyeglasses over a towel, so that if they slip they will not become scratched or broken. Use warm water and soap or a special cleansing preparation. Hot water may warp plastic lenses and frames. Rinse the glasses well after cleaning them with soap and water; dry them with a clean, soft cotton cloth. Paper products that are made of wood pulp increase the risk of scratching the lenses, so do not use a dry paper tissue to clean eyeglasses. Do not use silicone tissues to clean plastic lenses. CONTACT LENS CARE A contact lens is a small disc worn directly on the eyeball. It stays in place by surface tension of the eye’s tears. Contact lenses are either rigid (hard) or soft. Rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses are more inflexible than soft lenses Soft lenses may be used for daily wear or extended wear. Disposable soft lenses are also available. People who wear contact lenses need to take special precautions to keep the lenses free of microorganisms that may lead to eye infections and to avoid injuring or scratching the surface of the eye. Patients should always perform hand hygiene before touching eye surfaces and lenses. Caution lens wearers about eye irritation in the presence of noxious vapors or smoke. Also, remind lens wearers that lenses should not come into contact with cosmetics, soaps, or hair sprays because eye irritation may result. The cornea, which consists of dense connective tissue, does not have its own blood supply. It is nourished primarily by oxygen from the atmosphere and from tears. In a patient who wears contact lenses, the cornea requires more than its normal supply of oxygen because its metabolic rate increases. . If an eye injury is present, do not try to remove lenses because of the danger of causing an additional injury. ARTIFICIAL EYE CARE Most patients who wear an artificial eye prefer to care for it themselves if they are able. Encourage them to do so when possible. The necessary equipment includes a small basin, soap and water for washing, and solution for rinsing the prosthesis. Normal saline or tap water can be used for rinsing Guidelines for Nursing Care 31-3 REMOVING CONTACT LENSES If a patient wears contact lenses but is unable to remove them, use the following guidelines to safely remove them. Rigid Gas Permeable (RGP) Lenses If the lens is not centered over the cornea, apply gentle pressure on the lower eyelid to center the lens (Figure A). Gently pull the outer corner of the eye toward the ear (Figure B). Position the other hand below the lens to receive it and ask the patient to blink (Figure C). Alternately Gently spread the eyelids beyond the top and bottom edges of the lens (Figure D). Gently press lower eyelid up against the bottom of the lens (Figure E). After the lens is tipped slightly, move the eyelids toward one another to cause the lens to slide out between the eyelids (Figure F). Soft Contact Lenses Have the patient look forward. Retract the lower lid with one hand. Using the pad of the index finger on the other hand, move the lens down on the sclera (Figure G). Using the pads of the thumb and index finger, grasp the lens with a gentle pinching motion and remove (Figure H). Storing Lenses Storage cases are marked L and R, designating left and right lenses, as lenses may be different for each eye. It is important to place the first lens in its designated cup in the case before removing the second lens to avoid mixing them up (Figure I). (CONTINUE READING BOOK) Providing Environmental Care (***) Providing Environmental Care A patient’s environment can improve or detract from the person’s sense of well-being. A patient’s environment can consist of a room in a facility, such as a hospital, one or more rooms in the patient’s home or apartment, or something in-between. Regardless of the setting, ensure that the area is clean and clutter-free, safe, and pleasant. The patient’s environment in a hospital or other facility consists of the bedside unit and the furnishings and equipment in the space around the bed. Basic furniture includes the bed, overbed table, bedside stand, and chairs. Standard equipment in the health care environment includes the call light, oxygen, suction, and electrical outlets; light fixtures; bath basin; emesis basin; bedpan or urinal; water pitcher and glass; and bed linens Good ventilation in patient rooms is imperative to limit pathogens and unpleasant odors associated with body secretions and excretions; for example, urine, stool, vomitus, draining wounds, or body odors. In general, the room temperature should be between 68°F and 74°F (20°C and 23°C). Care should be taken to reduce harsh lighting and noises whenever possible, although adequate lighting is necessary for all nursing procedures. Before leaving the bedside, get into the habit of saying to the patient, “Is there anything else I can do to make you more comforta BED SAFETY AND COMFORT The typical hospital bed has a motorized frame in three sections, which allows the height of the bed to be raised or lowered and the head and foot to be adjusted. Know how to operate the bed and be ready to explain it to the patient. Bed positions are described i Nurses are responsible for ensuring the safety and comfort of the patient at the bedside. To promote bed safety while maintaining patient comfort, ensure the following before leaving the patient’s bedside: The bed is in its lowest position. The bed position is safe for the patient. The bed controls are functioning (bed is electrically safe). The call light is functioning and always within reach. Side rail(s) is/are raised if indicated or requested by the patient. The wheels or casters are locked. Facility policies usually dictate the availability and use of bed linens. Bed linens include mattress covers, sheets, incontinence pads, pillowcases, blankets, and bath blankets. To promote bed comfort, ensure the following before leaving a patient: Linens are clean and free of crumbs and wrinkles. The patient feels comfortably warm. Pressure areas are protected from rough sheets and water-repellent materials. This is especially important for patients with a nursing diagnosis of Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity. MAKING A BED A comfortable bed and appropriate bedding contribute to a patient’s sense of well-being. Usually bed linens are changed after the bath, but some facilities change linens only when soiled. The bed is made for the ambulatory patient, as described in CHAP 8. COMMUNICATION A. THE PROCESS OF COMMUNICATION B. FORM OF COMMUNICATION C. LEVEL OF COMMUNICATION D. FACTOR INFLUENCE COMMUNICATION E. EFFECTIVE PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION I. Hand-off Communication: SBAR (***) Hand-off communication involves the process of accurate presentation and acceptance of patient-related information from one caregiver or team to another caregiver or team. Hand-off communication occurs between nurses and other departments in the facility, during nurse-to-nurse report, or in nurse-to-physician/health care provider discussions SBAR, which stands for Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendations, provides a consistent method for hand-off communication that is clear, structured, and easy to use. . The S (Situation) and B (Background) provide objective data, whereas the A (Assessment) and R (Recommendations) allow for presentation of subjective information. I-SBAR-R and the QSEN Institute The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) Institute identifies quality and safety competencies for nursing, with the goal of preparing future nurses with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to improve the quality and safety of the health care systems within which they work This adapted form includes the initial identification of “yourself and your patient (I)” and the opportunity to ask and respond to questions, or “readback (R), USING PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION IN THE HELPING RELATIONSHIP DEVELOPING PROFESSIONAL THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION SKILLS (***)- P 166 BLOCKS TO COMMUNICATION- p172 (***) CHAP 24: ASEPSIS AND INFECTION CONTROL- 4 SKILLS P621 A. INFECTION I.INFECTION CYCLE II. STAGES OF INFECTION III. BODY DEFENSE AGAINST INFECTION IV.FACTOR AFFECTING RISK OF INFECTION CHAP 27: SAFETY, SECURITY AND EMERGENCY- 2 SKILLS P 783 A.FACTORS AFFECTING SAFETY DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS (***) B.NURSING PROCESS I.ASSESSMENT (FALL***) II.IMPLEMENTING CHAP 32: SKIN_ 8 SKILLS Skill 32-1 Preventing Pressure Injury Assessment: not UAP, but LPN Implement: both -Do not use foam rings, foam cut-outs, or donut-type devices. -Routinely reposition the patient; at least every 2 hours for bedridden patients and every hour for patients in a chair or wheelchair -Use a 30-degree side-lying position (lateral tilt position) when positioning patients at risk for pressure injury in side-lying positions - Maintain the head-of-bed elevation at or below 30 degrees, or at the lowest degree of elevation appropriate for the patient’s medical condition. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS Patient develops a pressure injury: Reassess the patient’s condition. Perform assessment to differentiate pressure injuries from wounds and/or injuries due to other causes (WOCN, 2016). Consult with the patient’s health care provider to report the injury and collaborate on a revised care plan. Review and revise the current nursing care plan to reflect the change in the patient’s status and ensure implementation of appropriate interventions. Implement appropriate wound care as prescribed Skill 32-2 Cleaning a Wound and Applying a Dressing (General Guidelines) Not UAP, but LPN -. Assess the patient for the possible need for nonpharmacologic pain-reducing interventions or analgesic medication before wound care dressing change. removing in the direction of hair growth and the use of a push–pull method (Figure 1). Push–pull method: lift a corner of the dressing away from the skin, and then gently push the skin away from the dressing/adhesive. Continue moving fingers of the opposite hand to support the skin as the product is removed -After removing the dressing, note the presence, amount, type, color, and odor of any drainage on the dressings (Figure 2). Place soiled dressings in the appropriate waste receptacle. Remove your gloves and dispose of them in an appropriate waste receptacle. Using sterile technique, prepare a sterile work area and open the needed supplies. Clean the wound. Clean from top to bottom and/or from the center to the outside 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. FIGURE 1. Loosening dressing tape or adhesive edge. 2. Noting characteristics of drainage on dressing that has been removed. 3. Cleaning the wound. 4. Applying skin protectant to skin surrounding wound. 5. Applying prescribed wound care product. FIGURE 6. Applying cover dressing to site UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS The previous wound assessment states that the incision was clean and dry and the wound edges were approximated, with the staples and surgical drain intact. The surrounding tissue was without inflammation, edema, or erythema. After the dressing is removed, the nurse notes the incision edges are not approximated at the distal end, multiple staples are evident in the old dressing, the surrounding skin tissue is red and swollen, and purulent drainage is on the dressing and leaking from the wound: Assess the patient for any other signs and symptoms, such as pain, malaise, fever, and paresthesias. Place a dry sterile dressing over the wound site. Report the findings to the primary health care provider and document the event in the patient’s record. Be prepared to obtain a wound culture and implement any changes in wound care as ordered. After the nurse has put on sterile gloves, the patient moves too close to the edge of the bed and the nurse must support her with his hands to prevent the patient from falling: If nothing else in the sterile field was touched, remove the contaminated gloves and put on new sterile gloves. If you did not bring a second pair, use the call bell to summon a coworker to provide a new pair of gloves. The nurse has set up dressing supplies, removed the old dressing, and put on sterile gloves to clean the wound. The nurse then realizes that a necessary piece of dressing material has been forgotten: Ask the patient to press the call bell to summon a coworker to provide the missing supplies. When removing a patient’s dressing, the assessment reveals eschar in the wound: Notify the primary health care provider or wound care specialist, as a different treatment modality and/or debridement may be necessary. Note: The presence of eschar in a pressure injury wound precludes staging the wound. The eschar must be removed for adequate pressure injury staging to be done. However, stable (dry, adherent, intact, without erythema or movement) eschar on pressure injuries on the heels serves as “the body’s natural Skill 32-3 Performing Irrigation of a Wound NOT UAP, BUT LPN - Analgesis for pain - Put on a gown, mask, and eye protection or face shield. - Using your nondominant hand, gently apply pressure to the basin against the skin below the wound - to form a seal with the skin Direct a stream of solution into the wound (Figure 3). Keep the tip of the syringe at least 1 in above the upper edge of the wound. Flush all wound areas. Once the wound is cleaned, dry the surrounding skin using a gauze sponge 1. Drawing up sterile solution from sterile container into irrigation syringe 2. Applying pressure to basin to form seal. 3. Irrigating wound with a stream of solution. Solution drains into collection container. 4. Drying around wound, not in wound, with gauze pad. FIGURE 5. Applying wound contact material. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS The patient experiences pain when the wound irrigation is begun: Stop the procedure and administer an analgesic, as prescribed. Obtain new sterile supplies and begin the procedure after an appropriate amount of time has elapsed to allow the analgesic to begin working. Note the patient’s pain on the nursing care plan so that pain medication can be given before future wound treatments. During the wound irrigation, the nurse notes bleeding from the wound. This has not been documented as happening with previous irrigations: Stop the procedure. Assess the patient for other symptoms. Obtain vital signs. Report the findings to the primary health care provider and document the event in the patient’s record. Skill 32-4 Caring for a Jackson–Pratt Drain ( Not UAP, but LPN) -Place the graduated collection container under the drain outlet. Without contaminating the outlet valve, pull off the cap. The chamber will expand completely as it draws in air. Empty the chamber’s contents completely into the container (Figure 1). Use the gauze pad to wipe the outlet. Fully compress the chamber with one hand and replace the cap with your other hand (Figure 2). -Check the patency of the equipment. Bulb should remain compressed. Check that the tubing is free from twists and kinks. -Secure the JP drain to the patient’s gown below the wound with a safety pin, making sure that there is no tension on the tubing. -If the drain site is open to air, observe the sutures that secure the drain to the skin. Look for signs of pulling, tearing, swelling, or infection of the surrounding skin. Gently clean the sutures with the gauze pad moistened with normal saline. Dry with a new gauze pad. Apply skin protectant/barrier to the surrounding skin. -Check drain status at least every 4 hours. Empty and reengage suction (compress device) when device is half to two thirds full. 1. Emptying contents of Jackson–Pratt drain into collection container. 2. Compressing Jackson–Pratt drain and replacing cap. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS A patient has a JP drain in the right lower quadrant following abdominal surgery. The record indicates it has been draining serosanguineous fluid, 40 to 50 mL every shift. While performing your initial assessment, you note that the dressing around the drain site is saturated with serosanguineous secretions and there is minimal drainage in the collection chamber: Inspect the tubing for kinks or obstruction. Assess the patient for changes in condition. Remove the dressing and assess the site. Often, if the tubing becomes blocked with a blood clot or drainage particles, the wound drainage will leak around the exit site of the drain. Cleanse the area and redress the site. Notify the primary health care provider of the findings and document the event in the patient’s record. Your patient calls you to the room and says, “I found this in the bed when I went to get up.” He has his JP drain in his hand. It is completely removed from the patient: Assess the patient for any new and abnormal signs or symptoms, and assess the surgical site and drain site. Apply a sterile dressing with gauze and tape to the drain site. Notify the primary health care provider of the findings and document the event in the patient’s record. Skill 32-5 Caring for a Hemovac Drain (not UAP, but LPN) - Place the graduated collection container under the drain outlet. Without contaminating the outlet, pull off the cap. The chamber will expand completely as it draws in air. Empty the chamber’s contents completely into the container (Figure 1). Use the gauze pad to wipe the outlet. Fully compress the chamber by pushing the top and bottom together with your hands. Keep the device tightly compressed while you apply the cap -Device should remain compressed. Check the patency of the equipment. Make sure the tubing is free from twists and kinks. -Secure the Hemovac drain to the patient’s gown below the wound with a safety pin, making sure that there is no tension on the tubing. 1. Emptying Hemovac drain into collection container. 2. Compressing Hemovac and securing cap. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS A patient has a Hemovac drain placed in the left knee following surgery. The record indicates it has been draining serosanguineous secretions, 40 to 50 mL every shift. While performing your initial assessment, you note that the collection chamber is completely expanded. The nurse empties the device and compresses to resume suction. A short time later, the nurse observes that the chamber is completely expanded again: Inspect the tubing for kinks or obstruction. Inspect the device, looking for breaks in the integrity of the chamber. Make sure the cap is in place and closed. Assess the patient for changes in condition. Remove the dressing and assess the site. Make sure the drainage tubing has not advanced out of the wound, exposing any of the perforations in the tubing. If you are not successful in maintaining the suction, notify the primary health care provider Skill 32-6 Collecting a Wound Culture (not UAP, but LPN) - Assess and clean the wound, using a nonantimicrobial cleanser, as outlined in - Dry the surrounding skin with gauze dressings. Put on clean gloves. -Twist the cap to loosen the swab on the Culturette tube, or open the separate swab(s) and remove the cap from the culture tube. Keep the swab and inside of the culture tube(s) sterile -. Identify a 1 cm area of the wound that is free from necrotic tissue. Carefully insert the swab into this area of clean viable tissue. Press the swab to apply sufficient pressure to express fluid from the wound tissue and rotate the swab several times. Avoid touching the swab to intact skin at the wound edges (Figure 3). -Place the swab back in the culture tube (Figure 4). Do not touch the outside of the tube with the swab. 1. Checking culture label with the patient’s identification band. 2. Removing cap from culture tube. 3. Rotating swab several times over wound surface. 4. Placing swab in culture tube. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS The nurse has inserted the culture swab into the patient’s wound to obtain the specimen and realizes that the wound was not cleaned: Discard this swab. Obtain the additional supplies needed to clean the wound according to facility policy and a new culture swab. Cleaning the wound prior to obtaining a specimen for culture removes previous drainage and wound debris, which could introduce extraneous organisms into the collected specimen, resulting in inaccurate results. Clean the wound using a nonantimicrobial cleanser and then proceed to obtain the culture specimen. As the nurse prepares to insert the culture swab into the wound, the nurse inadvertently touches the swab to the patient’s bedclothes or other surface: Discard this swab, obtain a new culture swab, and collect the specimen. Skill 32-7 Applying Negative Pressure Wound Therapy- not UAP, but LPN - If NPWT is currently in use, turn off the negative pressure unit. Put on clean, disposable gloves. Loosen the tape on the old dressings by removing in the direction of hair growth and the use of a push–pull method. Push– pull method: lift a corner of the dressing away from the skin, then gently push the skin away from the dressing/adhesive. -Note the presence, amount, type, color, and odor of any drainage on the dressings. Note the number of pieces of wound contact material removed from the wound. Compare with the documented number from the previous dressing change. - Put on sterile gloves. Wipe intact skin around the wound with a skin protectant/barrier wipe and allow it to dry. -If the use of a wound contact layer (impregnated porous gauze or silicone adhesive contact layer) is indicated, use sterile scissors to cut the wound contact layer to fit the wound bed. Apply wound contact layer to the wound bed. -Fit the wound contact material to the shape of the wound. If using foam wound contact material, use sterile scissors to cut the foam to the shape and measurement of the wound. Do not cut foam over the wound. More than one piece of foam may be necessary if the first piece is cut too small. Carefully place the foam in the wound (Figure 1). Ensure foam-to-foam contact if more than one piece is required. If using gauze wound filler, carefully place in wound to fill cavity. Note the number of pieces of wound filler placed in the wound. Do not under- or over-fill. -Trim and place the transparent adhesive drape to cover the wound contact material and an additional 3 to 5 cm border of intact periwound tissue (Figure 2). Avoid stretching the transparent adhesive drape tight over the wound. - Assess the dressing to ensure seal integrity. The dressing should be collapsed, shrinking to the wound contact material and skin (Figure 5). Observe drainage in tubing. 1. Cutting wound contact material (foam) to shape and measurement of wound. 2. Placing transparent adhesive drape to cover the wound. FIGURE 3. Cutting a hole in the drape. FIGURE 4. Applying the connecting pad over the hole. FIGURE 5. Dressing is collapsed, shrinking to wound contact material and skin. (Used with permission. Courtesy of KCI, an Acelity Company.) UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS While assessing the patient, the nurse notes that the seal between the transparent adhesive drape and the wound contact material and skin is not tight: Check the dressing seals, tubing connections, and canister insertion, and ensure the clamps are open. If a leak in the transparent drape is identified, the appropriate pressure is not being applied to the wound. Apply additional transparent dressing to reseal. If this application does not correct the break, change the dressing. The patient complains of acute pain while NPWT is operating: Assess the patient for other symptoms, obtain vital signs, assess the wound, and assess the vacuum device for proper functioning. Report your findings to the primary health care provider and document the event in the patient’s record. Administer analgesics, as ordered. Continue or change the wound therapy, as ordered. Some patients may be unable to tolerate NPWT and may require a change in the type of wound contact material used, addition of a wound contact layer, intermittent therapy cycling, a reduction in suction pressure, or discontinuation of the therapy Skill 32-8 Applying an External Heating Pad- both Plug in the unit and warm the pad before use. Apply the aquathermia pad to the prescribed area (Figure 3). Secure with gauze bandage or tape. Plugging in the pad readies it for use. Heat travels by conduction from one object to another. Gauze bandage or tape holds the pad in position; do not use pins, as they may puncture and damage the pad. -Monitor the condition of the skin and the patient’s response to the heat at frequent intervals, according to facility policy. Do not exceed the prescribed length of time for the application of heat. - After the prescribed time for the treatment (up to 30 minutes), remove the aquathermia pad. Do not exceed the prescribed amount of time. Reassess the patient and area of application, noting the effect and presence of any adverse effects. -1. External heating pad electronic unit. 2. Attaching pad tubing to electronic unit tubing. FIGURE 3. Applying heating pad to the prescribed area. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS When performing a periodic assessment of the site during the application of heat, the nurse notes excessive swelling and redness at the site and the patient complains of pain that was not present prior to the application of heat: Remove the heat source. Assess the patient for other symptoms and obtain vital signs. Report your findings to the primary health care provider and document the interventions in the patient’s record. CHAP 33: ACTIVITY Skill 33-1 Applying and Removing Graduated Compression STOCK- BOTH 1. Pulling graduated compression stocking inside-out. ocki 2. Putting foot of stocking onto patient. 3. Ensuring heel is centered after stocking is on foot. 4. Pulling stocking up leg. 5. Pulling stocking up over thigh. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS Patient’s leg measurements are outside the guidelines for the available sizes: Notify prescriber. Patient may require custom-fitted stockings. Patient has a lot of pain with application of stockings: If pain is expected (e.g., if the patient has a leg incision), it may be necessary to premedicate the patient and apply the stockings once the medication has had time to take effect. If the pain is unexpected, notify the primary care provider because the patient may be developing a deep vein thrombosis. Patient has an incision on the leg: When applying and removing stockings, be careful not to hit the incision. If the incision is draining, apply a small bandage to the incision so that it does not drain onto the stockings. If the stockings become soiled by drainage, wash and dry according to instructions. Patient is to ambulate with stockings: Place skid-resistant socks or slippers on before patient attempts to ambulate. Skill 33-2 Assisting a Patient With Turning in Bed- both -Review the medical orders and nursing care plan for patient activity. Identify any movement limitations and the ability of the patient to assist with turning. Consult patient handling algorithm, if available, to plan appropriate approach to moving the patient. 1. Having patient grasp side rail on side of bed toward which he or she is turning. 2. Standing opposite patient’s center with feet spread about shoulder width and with one foot ahead of the other. 3. Using friction-reducing sheet to position the patient over on her side. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS You are turning a patient by yourself, but you realize that the patient cannot help as much as you thought and is heavier than you anticipated: Use the call bell to summon assistance from a coworker. Alternatively, cover the patient, make sure all rails are up, lower the bed to the lowest position, and get someone to assist you. Consider using an algorithm for patient handling and movement to identify appropriate interventions, a friction-reducing sheet, and two to three additional caregivers. Skill 33-3 Moving a Patient Up in Bed With the Assistance of another caregiver- both -Review the medical record and nursing care plan for conditions that may influence the patient’s ability to move or to be positioned. Assess for tubes, IV lines, incisions, or equipment that may alter the positioning procedure. Identify any movement limitations. Consult patient handling algorithm, if available, to plan appropriate approach to moving the patient. 1. Nurses positioned at patient’s midsection, shifting weight from back leg to front leg in preparation for move. 2. Patient moved up in bed. 3. Adjusting bed to a safe and comfortable position UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS You are attempting to move a patient up in the bed with another nurse. Your first attempt is unsuccessful, and you realize the patient is too heavy for only two people to move: Obtain the assistance of at least two other coworkers. Make use of available friction-reducing devices. Use full-body lift, if available. Position opposing pairs at the patient’s shoulders and buttocks to distribute the weight. If necessary, have a fifth person lift the patient’s legs or heels. The movement of a very large patient is aided by putting the bed in a slight Trendelenburg position temporarily, provided the patient can tolerate it. Skill 33-4 Transferring a Patient From the Bed to a Stretcher- both Consult patient handling algorithm, if available, to plan appropriate approach to moving the patient. -Position the stretcher next (and parallel) to the bed. Lock the wheels on the stretcher and the bed. -Two nurses should stand on the stretcher side of the bed. A third nurse should stand on the side of the bed without the stretcher. Use the friction-reducing sheet to roll the patient away from the stretcher (Figure 1). Place the transfer board across the space between the stretcher and the bed, partially under the patient (Figure 2). Roll the patient onto his or her back, so that the patient is partially on the transfer board. 11. At a signal given by one of the nurses, have the nurses standing on the stretcher side of the bed pull the frictionreducing sheet. At the same time, the nurse (or nurses) on the other side push, transferring the patient’s weight toward the transfer board, and pushing the patient from the bed to the stretcher The transfer board or other lateral-assist device reduces friction, easing the workload to move patient. 1. Using sheet to roll patient away from stretcher. 2. Positioning transfer board under patient. 3. Transferring patient onto stretcher. 4. Securing patient on stretcher. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS Your patient needs to be transported to another department by stretcher. The patient is very heavy and somewhat confused, so you are concerned about his ability to cooperate with the transfer: Consult a Bariatric Algorithm. Obtain the assistance of three or more additional coworkers. Use a mechanical lateral-transfer device or air-assisted transfer device to move the patient Skill 33-5 Transferring a Patient From the Bed to a Chair- both Consult patient handling algorithm, if available, to plan appropriate approach to moving the patient. - Make sure the bed brakes are locked. Put the chair next to the bed. If available, lock the brakes of the chair. If the chair does not have brakes, brace the chair against a secure object. - 10. Stand in front of the patient and assess for any balance problems or complaints of dizziness (Figure 1). Allow the patient’s legs to dangle a few minutes before continuing. - Encourage the patient to make use of the stand-assist device. If necessary, have second staff person grasp the gait belt on opposite side. Rock back and forth while counting to three. On the count of three, using the gait belt and your legs (not your back), assist the patient to a standing position 2. Wrapping gait belt around patient’s waist. 1. Standing in front of patient and assessing for any balance problems or complaints of dizziness. 3. Standing close to patient and grasping gait belt. 4. Using gait belt and pushing with legs to help raise the patient to a standing position. 5. Assisting patient to sit. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS You are assisting a patient out of bed. The previous times the patient has gotten up, you have not had any difficulty helping him by yourself, so you are working alone at this time. The patient is positioned on the side of the bed. You flex your hips and knees to help him stand. As you move to pivot to the chair, the patient becomes very lightheaded and weak and his knees buckle. The patient is too heavy for you to lift to the chair: Do not continue the move to the chair. Lower the patient back to the side of the bed. Pivot him back into bed, cover him, and raise the side rails. Check vital signs and assess for any other symptoms. After his symptoms have subsided and you are ready to get him up again, arrange for the assistance of another staff member. Have the patient dangle his legs for a longer period of time before standing. Assess for lightheadedness or dizziness before helping him to stand. Notify the primary care provider if there are any significant findings or if his symptoms persist. CHAP 37: URINARY ELIMINATION-7SKILL Skill 37-1 Assessing Bladder Volume Using an Ultrasound – NOT UAP, BUT LPN Place the scanner head on the gel or gel pad, with the directional icon on the scanner head toward the patient’s head. Aim the scanner head toward the bladder (point the scanner head slightly downward toward the coccyx) Observe the image on the scanner screen. Adjust the scanner head to center the bladder image on the crossbars 3. A. Placing ultrasound gel about 1 to 1.5 in above symphysis pubis. Bl UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS You press wrong icon for the patient’s biological sex when initiating the scanner: Turn scanner off and back on. Re-enter information using correct biological sex button. You have reason to believe the bladder is full, based on assessment data, but scanner reveals little to no urine in bladder: Ensure proper positioning of scanner head. Place a generous amount of ultrasound gel or gel pad midline on the patient’s abdomen, about 1 to 1.5 in above the symphysis pubis. Place the scanner head on the gel or gel pad, with the directional icon on the scanner head toward the patient’s head. Aim the scanner head toward the bladder (point the scanner head slightly downward toward the coccyx). Ensure that the bladder image is centered on the crossbars. Skill 37-2 Assisting With the Use of a Bedpan-both Ask the patient to bend the knees. Have the patient lift his/her hips upward. Assist the patient, if necessary, by placing your hand that is closest to the patient palm up, under the lower back, and assist with lifting. Slip the bedpan into place with the other hand 10. Ensure that the bedpan is in proper position and the patient’s buttocks are resting on the rounded shelf of the regular bedpan or the shallow rim of the fracture bedpan. 1. Placing waterproof pad under patient’s buttocks. 2. Assisting patient to raise hips upward and positioning the bedpan. 3. Placing call bell within patient’s reach and handing patient toilet tissue. Skill 37-3 Assisting With the Use of a Urinal- both - Assist the patient to an appropriate position, as necessary: standing at the bedside, lying on one side or back, sitting in bed with the head elevated, or sitting on the side of the bed. - If the patient is not standing, have him spread his legs slightly. Hold the urinal close to the penis and position the penis completely within the urinal (Figure 1). Keep the bottom of the urinal lower than the penis. If necessary, assist the patient to hold the urinal in place. Skill 37-4 Applying an External Urinary Sheath (Condom – both - Roll the external urinary sheath outward onto itself. Grasp the penis firmly with the nondominant hand. Apply the external urinary sheath by rolling it onto the penis with the dominant hand (Figure 1). Leave 1 to 2 in (2.5 to 5 cm) of space between the tip of the penis and the end of the external urinary sheath. - 13. Apply pressure to the sheath at the base of the penis for 10 to 15 seconds. Connect the external urinary sheath to drainage setup (Figure 2). Avoid kinking or twisting drainage tubing. 1. Unrolling sheath onto penis. 2. Connecting external urinary sheath to drainage setup. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS External urinary sheath leaks with every voiding: Check the size of the external urinary sheath. If it is too big or too small, it may leak. Check the space between the tip of the penis and the end of the external urinary sheath. If this space is too small, the urine has no place to go and will leak out. External urinary sheath will not stay on patient: Ensure that the external urinary sheath is correct size and that the penis is thoroughly dried before applying the external urinary sheath. Remind the patient that the external urinary sheath is in place, so that he does not tug at the tubing. If the patient has a retracted penis, an external urinary sheath may not be the best choice; there are pouches made for patients with a retracted penis. When assessing the patient’s penis, you find a break in skin integrity: Do not reapply the external urinary sheath. Allow skin to be open to air as much as possible. If your facility has a wound, ostomy, and continence nurse, arrange for a consult. Skill 37-5 Catheterizing the Female Urinary Bladder- not UAP BUT LPN - 9. Assist the patient to a dorsal recumbent position with knees flexed, feet about 2 ft apart, with her legs abducted. Drape the patient (Figure 1). Alternately, the Sims’, or lateral, position can be used. Place the patient’s buttocks near the edge of the bed with her shoulders at the opposite edge and her knees drawn toward her chest (Figure 2). Allow the patient to lie on either side, depending on which position is easiest for the nurse and best for the patient’s comfort. Slide waterproof pad under the patient. - With thumb and one finger of nondominant hand, spread labia and identify meatus (Figure 4). Be prepared to maintain separation of labia with one hand until catheter is inserted and urine is flowing well and continuously. If the patient is in the side-lying position, lift the upper buttock and labia to expose the urinary meatus - Use the dominant hand to pick up an antiseptic swab or use forceps to pick up a cotton ball. Clean one labial fold, top to bottom (from above the meatus down toward the rectum), then discard the cotton ball (Figure 6). Using a new cotton ball/swab for each stroke, continue to clean the other labial fold, then directly over the meatus. - 21. Using your dominant hand, hold the catheter 2 to 3 in from the tip and insert slowly into the urethra (Figure 7). Advance the catheter until there is a return of urine (approximately 2 to 3 in [4.8 to 7.2 cm]). Once urine drains, advance the catheter another 2 to 3 in (4.8 to 7.2 cm). Do not force the catheter through the urethra into the bladder. Ask the patient to breathe deeply, and rotate the catheter gently if slight resistance is met as the catheter reaches the external sphincter. - Hold the catheter securely at the meatus with your nondominant hand. Use your dominant hand to inflate the catheter balloon (Figure 8). Inject the entire volume of sterile water supplied in a prefilled syringe. Remove the syringe from the port. - 26. Remove gloves. Secure catheter tubing to the patient’s inner thigh with a catheter-securing device (Figure 10). Leave some slack in the catheter for leg movement. 1. Patient in dorsal recumbent position and draped properly. 2. Demonstration of side-lying position. 3. Patient with fenestrated drape in place over perineum. 4. Using dominant hand to separate and hold labia open. 5. Exposing urinary meatus with patient in side-lying position. 6. Wiping perineum with cotton ball held by forceps. Wipe in one direction—from top to bottom. 7. Inserting catheter with dominant hand while nondominant hand holds labia apart. 8. Inflating balloon of indwelling catheter. 9. Attaching catheter to drainage bag. 10. Catheter secured to leg. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS No urine flow is obtained, and you note that the catheter is in the vaginal orifice: Leave the catheter in place as a marker. Obtain new sterile gloves and catheter kit. Start the procedure over and attempt to place the new catheter directly above the misplaced catheter. Once the new catheter is correctly in place, remove the catheter in the vaginal orifice. Because of the risk of cross-infection, never remove a catheter from the vagina and insert it into the urethra. Patient moves legs during procedure: If no supplies have been contaminated, ask patient to hold still and continue with the procedure. If supplies have been contaminated, stop the procedure and start over. If necessary, get an assistant to remind the patient to hold still. Urine flow is initially well established and urine is clear, but after several hours flow dwindles: Check the tubing for kinking. If patient has changed position, the tubing and drainage bag may need to be moved to facilitate drainage of urine. Urine leaks out of meatus around the catheter: Do not increase the size of the indwelling catheter. Make sure the smallest-sized catheter with a 10-mL balloon is used. Large catheters cause bladder and urethral irritation and trauma. Large balloon-fill volumes occupy more space inside the bladder and put added weight on the base of the bladder. Irritation of the bladder wall and detrusor muscle can cause leakage. If leakage persists, consider an evaluation for urinary tract infection. Ensure that the correct amount of solution was used to inflate the balloon. Underfilling the balloon can cause the catheter to dislodge into the urethra, causing urethral spasm, pain, and discomfort. If you suspect underfill, do not attempt to push the catheter farther into the bladder. Remove the catheter and replace. Assess the patient for constipation. Bowel full of stool can cause pressure on the catheter lumen and prevent the drainage of urine. Implement interventions to prevent/treat constipation. Skill 37-6 Catheterizing the Male Urinary Bladder-not UAP BUT LPN - Lift the penis with the nondominant hand. Retract the foreskin in an uncircumcised patient. Be prepared to keep this hand in this position until the catheter is inserted and urine is flowing well and continuously. Use the dominant hand to pick up an antiseptic swab or use forceps to pick up a cotton ball. Using a circular motion, clean the penis, moving from the meatus down the glans of the penis (Figure 2). Repeat this cleansing motion two more times, using a new cotton ball/swab each time. Discard each cotton ball/swab after one use. - 18. Hold the penis with slight upward tension and perpendicular to the patient’s body. Use the dominant hand to pick up the lubricant syringe. Gently insert the tip of the syringe with a lubricant into the urethra and instill the 10 mL of lubricant - 19. Use the dominant hand to pick up the catheter and hold it an inch or two from the tip. Ask the patient to bear down as if voiding. Insert the catheter tip into the meatus (Figure 4). Ask the patient to take deep breaths. Advance the catheter to the bifurcation or “Y” level of the ports. Do not use force to introduce the catheter. If the catheter resists entry, ask the patient to breathe deeply and rotate the catheter slightly. - 20. Hold the catheter securely at the meatus with your nondominant hand. Use your dominant hand to inflate the catheter balloon. Inject the entire volume of sterile water supplied in a prefilled syringe. Remove the syringe from the port. Once the balloon is inflated, the catheter may be gently pulled back into place. Replace foreskin, if present, over the catheter. Lower the penis. 1. Patient lying supine with fenestrated drape over penis. 2. Lifting penis with gloved nondominant hand and cleaning meatus with cotton ball held with forceps in gloved dominant hand. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS You cannot insert the catheter past 3 to 4 in; rotating the catheter and having the patient breathe deeply are of no help: If still unable to place the catheter, notify the primary care provider. Repeated catheter placement attempts can traumatize the urethra. The primary care provider may order and insert a coudé catheter. Patient is obese or has retracted penis: Have an assistant available to place fingers on either side of the pubic area and press backward to bring the penis out of the pubic cavity. Hold the patient’s penis up and forward. The catheter still needs to be inserted to the bifurcation; the length of the urethra has not changed. Urine leaks out of the meatus around the catheter: Do not increase the size of the indwelling catheter. Make sure the smallest-sized catheter with a 10-mL balloon is used. Large catheters cause bladder and urethral irritation and trauma. Large, balloon-fill volumes occupy more space inside the bladder and put added weight on the base of the bladder. Irritation of the bladder wall and detrusor muscle can cause leakage. If leakage persists, consider an evaluation for urinary tract infection. Ensure that the correct amount of solution was used to inflate the balloon. Underfilling the balloon can cause the catheter to dislodge into the urethra, causing urethral spasm, pain, and discomfort. If underfill is suspected, do not attempt to push the catheter farther into the bladder. Remove the catheter and replace it. Assess the patient for constipation. Bowel full of stool can cause pressure on the catheter lumen and prevent the drainage of urine. Implement interventions to prevent/treat constipation. Urine flow is initially well established and urine is clear, but after several hours urine flow dwindles: Check tubing for kinking. If the patient has changed position, the tubing and drainage bag may need to be moved to facilitate drainage of urine. Skill 37-7 Emptying and Changing a Stoma Appliance on a Urinary Diversion-both Emptying the Appliance 1. Emptying urine into graduated container. Changing the Appliance 11. Place a disposable waterproof pad on the overbed table or other work area. Open the premoistened disposable washcloths or set up the washbasin with warm water and the rest of the supplies. Place a trash bag within reach. 2. Gently removing appliance faceplate from skin. 3. Pushing skin from appliance rather than pulling appliance from skin. 4. Cleaning stoma with cleansing agent and washcloth. 5. Placing one or two gauze squares over stoma opening. 6. Cutting the faceplate opening 1/8 in larger than stoma size. 7. Applying faceplate over stoma. 16. Gently pat area dry. Make sure skin around stoma is thoroughly dry. Assess stoma and condition of surrounding skin. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS You remove appliance and find an area of skin excoriated: Make sure that the appliance is not cut too large. Skin that is exposed inside of the ostomy appliance will become excoriated. Assess for the presence of a fungal skin infection. If present, consult with primary care provider to obtain appropriate treatment. Cleanse the skin thoroughly and pat dry. Apply products made for excoriated skin before placing appliance over stoma. Frequently check faceplate to ensure that a seal has formed and that there is no leakage. Confer with primary care provider for a wound, ostomy, and continence nurse consult to manage these issues. Document the excoriation in the patient’s chart. Faceplate is leaking after applying a new appliance: Remove appliance, clean the skin, and start over. You are ready to place the faceplate and notice that the opening is cut too large: Discard appliance and begin over. A faceplate that is cut too big may lead to excoriation of the skin. Stoma is dark brown or black: Stoma should appear pink to red, shiny, and moist. Alterations indicate compromised circulation. If the stoma is dark brown or black, suspect ischemia and necrosis. Notify the primary care provider immediately. CHAP 38: BOWEL ELIMINATION Skill 38-1 Administering a Large-Volume Cleansing Enema-BOTH 1. Adjusting height of solution container until it is no more than 18 in above patient. 2. Inserting enema tip into anus, directing tip toward umbilicus. 3. Holding bag lower to slow flow of enema solution 4. Clamping tubing before removing. FIGURE 5. Offering toilet tissue to patient on bedside commode. If resistance is met while inserting the tube, permit a small amount of solution to enter, withdraw the tube slightly, and then continue to insert it. Do not force entry of the tube. Ask the patient to take several deep breaths - Introduce solution slowly over a period of 5 to 10 minutes. Hold tubing all the time that solution is being instilled. Assess for dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, diaphoresis, and clammy skin during administration. If the patient experiences any of these symptoms, stop the procedure immediately, monitor the patient’s heart rate and blood pressure, and notify the primary care provider. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS Solution does not flow into rectum: Reposition rectal tube. If solution will still not flow, remove the tube and check for any fecal contents. Patient cannot retain enema solution for adequate amount of time: Patient may need to be placed on bedpan in the supine position while receiving the enema. The head of the bed may be elevated 30 degrees for the patient’s comfort. Patient cannot tolerate large amount of enema solution: Amount and length of administration may have to be modified if patient begins to complain of pain. Patient complains of severe cramping with introduction of enema solution: Lower solution container and check the temperature and flow rate. If the solution is too cold or flow rate too fast, severe cramping may occur. Skill 38-2 Inserting a Nasogastric Tube-NOT uap, but lpn 7. Measure the distance to insert the tube by placing the tube tip at the patient’s nostril and extending it to the tip of the earlobe (Figure 1) and then to tip of the xiphoid process (Figure - When pharynx is reached, instruct the patient to touch chin to chest. Encourage the patient to sip water through a straw or swallow (Figure 4). Advance the tube in downward and backward direction when patient swallows. Stop when the patient breathes. If gagging and coughing persist, stop advancing the tube and check placement of the tube with a tongue blade and flashlight. If the tube is curled, straighten the tube and attempt to advance again. Keep advancing the tube until pen marking is reached. Do not use force. Rotate the tube if it meets resistance. 11. Discontinue the procedure and remove the tube if there are signs of distress, such as gasping, coughing, cyanosis, and inability to speak or hum. For additional support, tape the tube onto the patient’s cheek using a piece of tape. If a double-lumen tube (e.g., Salem sump) is used, secure the vent above stomach level. Attach the vent at shoulder level 1. Measuring NG tube from nostril to tip of earlobe. 2. Measuring NG tube from tip of earlobe to xiphoid process. 3. Beginning insertion with patient positioned with head slightly flexed back. 4. Advancing tube after patient drops chin to chest and while swallowing. . Making a 2-in cut into a 4-in strip of tape. 6. Applying tape to patient’s nose. 7. Wrapping split ends around NG tube. 8. NG tube attached to wall suction 9. Patient with Salem sump tube (NG) secured. Note blue vent at patient’s shoulder. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS As a tube is passing through the pharynx, the patient begins to retch and gag: This is common during placement of an NG tube. Ask the patient if he or she wants the nurse to stop the procedure, which will allow the patient to gain composure from the gagging episode. Continue to advance the tube when the patient relates that he or she is ready. Have the emesis basin nearby in case the patient begins to vomit. The nurse is unable to pass the tube after trying a second time down the one nostril: If the patient’s condition permits, inspect the other nostril and attempt to pass the NG tube down this nostril. If unable to pass down this nostril, consult another health professional. As the tube is passing through the pharynx, the patient begins to cough and shows signs of respiratory distress: Stop advancing the tube. The tube is most likely entering the trachea. Pull the tube back into the nasal area. Support the patient as he or she regains normal breathing ability and composure. If the patient feels that he or she can tolerate another attempt, ask the patient to keep chin on chest and swallow as the tube is advanced to help prevent the tube from entering the trachea. Begin to advance the tube, watching for any signs of respiratory distress. No gastric contents can be aspirated: Reposition the patient and flush the tube with 30 mL of air in a large syringe. Slowly apply negative pressure to withdraw fluid. Skill 38-3 Removing a Nasogastric Tube- not UAP but LPN Check placement (as outlined in Skill 38-2 on pages 1457–1462) and flush with 10 mL of water or normal saline solution (optional) or clear with 30 to 50 mL of air (Figure 2). Clamp the tube with fingers by doubling the tube on itself (Figure 3). Instruct the patient to take a deep breath and hold it. Quickly and carefully remove the tube while the patient holds breath. Coil the tube in the disposable pad as you remove it from the patient. 1. Placing towel or disposable pad across patient’s chest. 2. Flushing NG tube with 10-mL water. 3. Doubling tube on itself. 4. Measuring the amount of nasogastric drainage in collection device. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS Within 2 hours after NG tube removal, the patient’s abdomen is showing signs of distention: Notify primary care provider. Anticipate order to reinsert the NG tube. Epistaxis occurs with removal of the NG tube: Occlude both nares until bleeding has subsided. Ensure that patient is in upright position. Document epistaxis in patient’s medical record. Skill 38-4 Irrigating a Nasogastric Tube Connected to Suction-not UAP, BUT LPN Put on gloves. Place waterproof pad on the patient’s chest, under connection of the NG tube and suction tubing. Check placement of the NG tube. - Place tip of the syringe in the tube. If Salem sump or double-lumen tube is used, make sure that the syringe tip is placed in the drainage port and not in blue air vent. Hold the syringe upright and gently insert the irrigant (Figure 4) (or allow solution to flow in by gravity if facility policy or medical order indicates). Do not force solution into the tube. - 11. If unable to irrigate the tube, reposition patient and attempt irrigation again. Inject 10 to 20 mL of air and aspirate again. If repeated attempts to irrigate the tube fail, consult with primary care provider or follow facility policy. 1. Preparing syringe with 30 mL of irrigation solution. 2. Clamping nasogastric tube while disconnecting. 3. Holding both tubes upright to prevent leakage of gastric fluid. 4. Gently instilling irrigation. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS Flush solution is meeting a lot of force when plunger is pushed: Inject 20 to 30 mL of free air through the NG tube into the stomach in an attempt to reposition the tube and enable flushing of the tube. The tube is connected to suction as ordered, but nothing is draining from the tube: First, check the suction canister to ensure that the suction is working appropriately. Disconnect the NG tube from suction and place your gloved thumb over the end of the suction tubing. If there is suction present, the problem lies in the tube itself. Next, attempt to flush the tube to ensure its patency. After flushing the tube, the tube is not reconnected to suction as ordered: Reconnect the tube to suction as soon as error is noticed. Assess the abdomen for distention and ask the patient if he or she is experiencing any nausea or any abdominal discomfort. Complete any paperwork per institutional policy, such as a variance report. Skill 38-5 Emptying and Changing an Ostomy Appliance- both 1. Removing clamp, getting ready to empty pouch 2. Emptying contents of appliance into a measuring device. 3. Wiping lower 2 in of pouch with paper towel. Changing 4. Gently removing appliance. 5. Using toilet tissue to wipe around stoma. 6. Assessing stoma and peristomal skin. 7. Using measurement guide to measure size of stoma. 8. Tracing the same-sized circle on back and center of skin barrier. 9. Cutting the opening 1/8 in larger than stoma size. 10. Removing paper backing on faceplate. 11. Easing appliance over stoma 12. Using clip to close bottom of appliance. UNEXPECTED SITUATIONS AND ASSOCIATED INTERVENTIONS Peristomal skin is excoriated or irritated: Make sure that the appliance is not cut too large. Skin that is exposed inside of the ostomy appliance will become excoriated. Assess for the presence of a fungal skin infection. If present, consult with the primary care provider to obtain appropriate treatment. Thoroughly cleanse skin and apply skin barrier. Allow to dry completely. Reapply pouch. Monitor pouch adhesion and change pouch as soon as there is a break in adhesion. Confer with primary care provider for a wound, ostomy, and continence nurse consult to manage these issues. Document the excoriation in the patient’s chart. Patient continues to notice odor: Check system for any leaks or poor adhesion. Clean outside of bag thoroughly when emptying. Bag continues to come loose or fall off: Thoroughly cleanse skin and apply skin barrier. Allow to dry completely. Reapply pouch. Monitor pouch adhesion and change pouch as soon as there is a break in adhesion. Stoma is protruding into bag: This is called a prolapse. Have the patient rest for 30 minutes. If the stoma is not back to normal size within that time, notify primary care provider. If stoma stays prolapsed, it may twist, resulting in impaired circulation to the stoma. Stoma is dark brown or black: Stoma should appear pink to red, shiny and moist. Alterations indicate compromised circulation. If the stoma is dark brown or black, suspect ischemia and necrosis. Notify the primary care provider immediately.