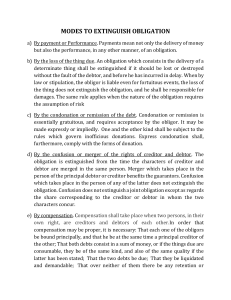

SECTION 5. COMPENSATION ART. 1278. Compensation shall take place when two persons, in their own right, are creditors and debtors of each other. Meaning of compensation. Compensation is the extinguishment to the concurrent amount of the debts of two persons who, in their own right, are reciprocally principal debtors and creditors of each other. (Arts. 1278, 1290.) Compensation and payment distinguished. 1. Compensation takes effect by operation of law, while payment takes effect by act of the parties; 2. In compensation, it is not required that the parties have the capacity to give or to receive, as the case may be (Art. 1290.), while in order that there may be a valid payment, the parties must have the free disposal of the thing due and capacity to alienate it (Art. 1239.) and to receive payment (Arts. 1240-1241.), as the case may be; and 3. In compensation, the law permits partial extinguishment of the obligation (Art. 1281.), while in payment, it is necessary that it be complete (Art. 1233.) and indivisible. (Art. 1248.) Compensation and counterclaim distinguished. The differences are: 1. While compensation resembles in many respects the common law set-off and certain counterclaims, it differs therefrom in that the latter must be pleaded to be effectual, whereas, compensation takes place by mere operation of law, and extinguishes reciprocally the two debts as soon as they exist simultaneously, to the amount of their respective; 2. Compensation requires that both debts consist in money, or if the things due are consumable, they be of the same kind and quality (Art. 1279[2].), while in counterclaim, such requirement is not provided; and 3. Compensation requires that the two debts must be liquidated, while in counterclaim, there is no such requirement. Kinds of Compensation 1. By its effect or extent. Total- when both obligations are of the same amount. Partial- when the two obligations are of different amounts. 2. By its cause or origin: Legal- when it takes place by operation of law even without the knowledge of the parties. Voluntary- when it takes place by agreement of the parties. 3. Judicial- when it takes place by order from a court of litigation. 4. Facultative- when it can be set up only by one of the parties. EXAMPLE: A owes B the amount of P1,000.00. B owes A the amount of P700.00. ART. 1279. In order that compensation may be proper, it is necessary: (1) That each one of the obligors be bound principally, and that he be at the same time a principal creditor of the other; (2) That both debts consist in a sum of money, or if the things due are consumable, they be of the same kind, and also of the same quality if the latter has been stated; (3) That the two debts be due; (4) That they be liquidated and demandable; (5) That over neither of them there be any retention or controversy, commenced by third persons and communicated in due time to the debtor. ART. 1280. Notwithstanding the provisions of the preceding article, the guarantor may set up compensation as regards what the creditor may owe the principal debtor. (1197) Compensation benefits guarantor. This article is an exception to the general rule that only the principal debtor can set up against his creditor what the latter owes him. Although the guarantor is only subsidiarily, not principally bound, he is given the right to set up compensation. ART. 1281. Compensation may be total or partial. When the two debts are of the same amount, there is a total compensation. (n) Total and partial compensations. Total or partial compensation applies to all the different kinds of compensation. Total compensation results when the two debts are of the same amount. If they are of different amounts, compensation is total as regards the smaller debt, and partial only with respect to the larger debt. (supra.) ART. 1282. The parties may agree upon the compensation of debts which are not yet due. (n) Voluntary compensation. This provision of law is an exception to the general rule that only debts which are due and demandable can be compensated. Voluntary or conventional compensation includes any compensation which takes place by agreement of the parties even if all the requisites for legal compensation are not present. ART. 1283. If one of the parties to a suit over an obligation has a claim for damages against the other, the former may set it off by proving his right to said damages and the amount thereof. (n) Judicial compensation. Compensation may also take place when so declared by a final judgment of a court in a suit. A party may set off his claim for damages against his obligation to the other party by proving his right to said damages and the amount thereof. ART. 1284. When one or both debts are rescissible or voidable, they may be compensated against each other before they are judicially rescinded or avoided. (n) Compensation of rescissible or voidable debts. Rescissible (Art. 1381.) and voidable obligations (Art. 1390.) are valid until they are judicially rescinded or avoided. Prior to rescission or annulment, the debts may be compensated against each other. EXAMPLE: A owes B P10,000.00. Subsequently, A, through fraud was able to make B sign a promissory note that B is indebted to A for the same amount. The debt of A is valid but that of B is voidable. Before the debt of B is nullified, both debts may be compensated against each other if all the requisites for legal compensation are present. (Art. 1279.) ART. 1285. The debtor who has consented to the assignment of rights made by a creditor in favor of a third person, cannot set up against the assignee the compensation which would pertain to him against the assignor, unless the assignor was notified by the debtor at the time he gave his consent, that he reserved his right to the compensation. - If the creditor communicated the cession to him but the debtor did not consent thereto, the latter may set up the compensation of debts previous to the cession, but not of subsequent ones. - If the assignment is made without the knowledge of the debtor, he may set up the compensation of all credits prior to the same and also later ones until he had knowledge of the assignment. (1198a) Where compensation has taken place before assignment. When compensation takes effect by operation of law or automatically, the debts are extinguished to the concurrent amount. (Art. 1290.) If subsequently, the extinguished debt is assigned by the creditor to a third person, the debtor can raise the defense of compensation with respect to the debt. It is well-settled that the rights of the assignee are not any greater than the rights of the assignor since the assignee is merely substituted in the place of the assignor. The remedy of the assignee is against the assignor. Of course, the right to the compensation may be waived by the debtor before or after the assignment. EXAMPLE: A owes B P3,000.00 due yesterday. B owes A P1,000.00 due also yesterday. Both debts are extinguished up to the amount of P1,000.00. Hence, A still owes B P2,000.00 today. Now, if B assigns his right to C, the latter can collect only P2,000.00 from A. However, if A gave his consent to the assignment before it was made or subsequently (par. 1.), A loses the right to set up the defense of compensation. So, A will be liable to C for P3,000.00 but he can still collect the P1,000.00 owed by B. In other words, the compensation shall be deemed not to have taken place. Where compensation has taken place after assignment. Article 1285 speaks of three cases of compensation which take place after an assignment of rights made by the creditor: (1) Assignment with the consent of the debtor. EXAMPLE: A owes B P3,000.00 due November 15. B owes A P1,000.00 due November 15. B assigned his right to C on November 1 with the consent of A. On November 15, A cannot set up against C, the assignee, the compensation which would pertain to him against B, the assignor. In other words, A is liable to C for P3,000.00 but he can still collect the P1,000.00 debt of B. (2) Assignment with the knowledge but without the consent of the debtor. EXAMPLE: A owes B P1,000.00 due November 1. B owes A P2,000.00 due November 10. A owes B P1,000.00 due November 15. A assigned his right to C on November 12. A notified B but the latter did not give his consent to the assignment. How much can C collect from B? B can set up the compensation of debts on November 10 which was before the cession on November 12. (par. 2.) There being partial compensation, the assignment is valid only up to the amount of P1,000.00. But B cannot raise the defense of compensation with respect to the debt of A due on November 15 which has not yet matured. So, on November 12, B is liable to C for P1,000.00. Come November 15, A will be liable for his debt of P1,000.00 to B. (3) Assignment without the knowledge of the debtor. EXAMPLE: In the preceding example, let us suppose that the assignment was made without the knowledge of B who learned of the assignment only on November 16. In this case, B can set up the compensation of credits before and after the assignment. The crucial time is when B acquired knowledge of the assignment and not the date of the assignment. If B learned of the assignment after the debts had already matured, he can raise the defense of compensation; otherwise, he cannot. ART. 1286. Compensation takes place by operation of law, even though the debts may be payable at different places, but there shall be an indemnity for expenses of exchange or transportation to the place of payment. (1199a) Compensation where debts payable at different places. This article applies to legal compensation. The indemnity contemplated above does not refer to the difference in the value of the things in their respective places but to the expenses of monetary exchange (in case of money debts) and expenses of transportation (in case of things to be delivered). Once these expenses are liquidated, the debts also become compensable. The indemnity shall be paid by the person who raises the defense of compensation. Foreign exchange has been defined as the conversion of an amount of money or currency of one country into an equivalent amount of money or currency of another. EXAMPLES: A owes B $1,000.00 payable in New York. B owes A P28,000.00 (equivalent amount) payable in Manila. If A claims compensation, he must pay for the expenses of exchange. ART. 1287. Compensation shall not be proper when one of the debts arises from a depositum or from the obligations of a depositary or of a bailee in commodatum. Neither can compensation be set up against a creditor who has a claim for support due by gratuitous title, without prejudice to the provisions of paragraph 2 of Article 301. (1200a) This article uses the “depositum” instead of “deposit” which is used for an ordinary bank deposit. A bank deposit is not a depositum as defined above. It is really a loan which creates the relationship of debtor and creditor. A bank’s failure to honor a deposit of money is failure to pay its obligation as debtor and not a breach of trust arising from depositary’s failure to return the thing deposited. EXAMPLE: A owes 10,000 to B. A deposited a ring worth 10,000.00 to B. B failed to return the ring ` to A. If B claims for compensation, there will be a breach of confidence. ART. 1288. Neither shall there be compensation if one of the debts consists in civil liability arising from a penal offense. Legal compensation not allowed by law: (1) Where one of the debts arises from a depositum. – A deposit is constituted from the moment a person receives a thing belonging to another with the obligation of safely keeping it and of returning the same. (Art. 1962.) EXAMPLE: A owes B P1,000.00. B, in turn, owes A the amount of P1,000.00 representing the value of a ring deposited by A with B, which B failed to return. (2) Where one of the debts arises from a commodatum. — Commodatum is a gratuitous contract whereby one of the parties delivers to another something not consumable so that the latter may use the same for a certain time and return it. (Art. 1933.) EXAMPLE: In the preceding example, if B borrowed the ring of B cannot refuse to return the ring on the ground of compensation because no compensation can take place when one of the debts arises from a commodatum. (3) Where one of the debts arises from a claim for support due by gratuitous title. — “Support comprises everything that is indispensable for sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family. EXAMPLES: (1) B is the father of A, a minor, who under the law is entitled to be supported by B. Now A owes B P1,000.00. B cannot compensate his obligation to support A by what A owes him because the right to receive support cannot be compensated with what the recipient (A) owes the obligor (B). The right to receive support cannot be compensated because it is essential to the life of the recipient. (Report of the Code Commission, p. 90.) (4) Where one of the debts consists in civil liability arising from a penal offense. — “If one of the debts consists in civil liability arising from a criminal offense, compensation would be improper and inadvisable because the satisfaction of such obligation is imperative.” EXAMPLE: A owes B P1,000.00. B stole the ring of A worth P1,000.00. Here, compensation by B is not proper. But A, the offended party, can claim the right of compensation. The prohibition in Article 1288 pertains only to the accused but not to the victim of the crime. ART. 1289. If a person should have against him several debts which are susceptible of compensation, the rules on the application of payments shall apply to the order of the compensation. (1201) Rules on application of payments applicable to order of compensation. Compensation is similar to payment. If a debtor has various debts which are susceptible of compensation, he must inform the creditor which of them shall be the object of compensation. In case he fails to do so, then the compensation shall be applied to the most onerous obligation. (Arts. 1252, 1254.) ART. 1290. When all the requisites mentioned in Article 1279 are present, compensation takes effect by operation of law, and extinguishes both debts to the concurrent amount, even though the creditors and debtors are not aware of the compensation. (1202a) Consent of parties not required in legal compensation. 1. Compensation occurs automatically by mere operation of law. — From the moment all the requisites mentioned in Article 1279 concur, legal compensation takes place automatically even in the absence of agreement between the parties and even against their will, and extinguishes reciprocally both debts as soon as they exist simultaneously, to the amount of their respective sums. It takes place ipso jure from the day all the necessary requisites concur, without need of any conscious intent on the part of the parties and even without their knowledge, at the time of the co-existence of such cross debts. 2. Full legal capacity of parties not required. — As it takes place by mere operation of law, and without any act of the parties, it is not required that the parties have full legal capacity (see Art. 37.) to give or to receive, as the case may be. On the other hand, in order that there may be a valid payment, the parties must have the free disposal of the thing due and capacity to alienate it (see Art. 1239.) and to receive payment (see Arts. 1240-1241.), as the case may be. Compensation, a matter of defense. Although compensation is produced by operation of law, it is usually necessary to set it up a defense in an action demanding performance. Once proved, its effects retroact or relate back to the very day on which all the requisites mentioned by law concurred or are fulfilled. SECTION 6. NOVATION ART. 1291. Obligations may be modified by: (1) Changing their object or principal conditions; (2) Substituting the person of the debtor; (3) Subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor. (1203) Meaning of novation. Novation is the total or partial extinction of an obligation through the creation of a new one which substitutes it. It is the substitution or change of an obligation by another, which extinguishes or modifies the first, either by changing its object or principal conditions, by or substituting another in place of the debtor, or by subrogating a third person in the rights of the creditor. Kinds of novation. 1. According to origin: (a) Legal. — that which takes place by operation of law (Arts. 1300, 1302; see Art. 1224.); or (b) Conventional. — that which takes place by agreement of the parties. (Arts. 1300, 1301.) 2. According to how it is constituted: (a) Express. — when it is so declared in unequivocal terms (Art. 1292.); or (b) Implied. — when the old and the new obligations are essentially incompatible with each other. 3. According to extent or effect: (a) Total or extinctive. — when the old obligation is completely extinguished; or (b) Partial or modificatory. — when the old obligation is merely modified, i.e., the change is merely incidental to the main obligation. 4. According to the subject: (a) Real or objective. — when the object (or cause) or principal conditions of the obligation are changed (Art. 1291[1].); (b) Personal or subjective. — when the person of the debtor is substituted and/or when a third person is subrogated in the rights of the; or (c) Mixed. — when the object or principal condition of the obligation and the debtor or the creditor or both the parties, are changed. It is a combination of real and personal novations. ART. 1292. In order that an obligation may be extinguished by another which substitutes the same, it is imperative that it be so declared in unequivocal terms, or that the old and the new obligations be on every point incompatible with each other. (1204) Requisites of novation. In novation, there are four (4) essential requisites, namely: 1. The existence of a previous valid obligation; 2. The intention or agreement and capacity of the parties to extinguish or modify the obligation; 3. The extinguishment or modification of the obligation; and 4. The creation or birth of a valid new obligation. Novation of judgment. A final judgment of a court that had been executed but not yet fully satisfied, may be novated by compromise. Novation with respect to criminal liability. Novation is not a mode of extinguishing criminal liability. It may prevent the rise of criminal liability as long as it occurs prior to the filing of the criminal information in court. In other words, novation does not extinguish criminal liability but may only prevent its rise. Novation not presumed. While as a general rule, no form of words or writing is necessary to give effect to a novation, it must be clearly and unmistakably established by express agreement or by the acts of the parties, as novation is never presumed. Ways of effecting conventional novation. There are only two (2) ways which indicate the presence of novation and thereby produce the effect of extinguishing an obligation by another which substitutes the same. Burden of showing novation. The burden of establishing a novation is on the party who asserts its existence. The necessity to prove the same by clear and convincing evidence is accentuated where the obligation of the debtor has already matured. Incompatibility between two obligations or contracts. 1. Incompatibility in any of the essential elements of obligation. — When not expressed, incompatibility is required so as to ensure that the parties have indeed intended such novation despite their failure to express it in categorical terms. 2. Test of incompatibility. — The test is whether they can stand together without conflict, each one having its own independent existence. If they cannot, they are incompatible, and the subsequent obligation novates the first. Effect of modifications of original obligation. 1. Slight modifications and variations. — When made with the consent of the parties, they do not abrogate the entire contract and the rights and obligations of the parties thereto, but the original contract continues in force except as the altered terms and conditions of the obligation are considered to be the essence of the obligation itself. 2. Material deviations or changes. — Where the original contract is deviated from in material respects so that the object or principal condition cannot reasonably be recognized as that originally contracted for, the original contract should be treated as abandoned. ART. 1293. Novation which consists in substituting a new debtor in the place of the original one, may be made even without the knowledge or against the will of the latter, but not without the consent of the creditor. Payment by the new debtor gives him the rights mentioned in Articles 1236 and 1237. (1205a) Kinds of personal novation. Personal novation may be in the form of: 1. Substitution. — when the person of the debtor is substituted (Art. 1291[2].); or 2. Subrogation. — when a third person is subrogated in the rights of the creditor. (Art. 1300.) Kinds of substitution. Article 1293 speaks of substitution which, in turn, may be: 1. Expromision or that which takes place when a third person of his own initiative and without the knowledge or against the will of the original debtor assumes the latter’s obligation with the consent of the creditor. 2. Delegacion or that which takes place when the creditor accepts a third person to take the place of the debtor at the instance of the latter. The creditor may withhold approval. (Art. 1295.) In delegacion, all the parties, the old debtor, the new debtor, and the creditor must agree. Right of new debtor who pays. 1. In expromision, payment by the new debtor gives him the right to beneficial reimbursement under the second paragraph of Article 1236. 2. If the payment was made with the consent of the original debtor or on his own initiative (delegacion), the new debtor is entitled to reimbursement and subrogation under Article 1237. Acceptance by creditor of payment from a third person. It is a common thing in business affairs for a stranger to a contract to assume its obligations, and while this may have the effect of adding to the number of persons liable, it does not necessarily imply the extinguishment of the liability of the first debtor. Consent of creditor necessary to substitution. In both the two modes of substitution (supra.), the consent of the creditor is an indispensable requirement. 1. Substitution implies waiver by creditor of his credit. — Since novation of a contract by substitution of a new debtor extinguishes the personality of the first debtor, it implies on the part of the creditor a waiver of the right he had before the novation. 2. Substitution may be prejudicial to creditor. — The requirement is based on simple consideration of justice since the consequence of the substitution may be prejudicial to the creditor and such prejudice may take the form of delay in the fulfillment of the obligation, or contravention of its tenor, or non-performance thereof by the new debtor (see 8 Manresa 436.), by reason of his financial inability or insolvency. 3. Creditor has right to refuse payment by third person without interest in obligation. — It is also consistent with the rule that a creditor cannot be compelled to accept payment or performance by a third person who has no interest in the fulfillment of the obligation. (see Art. 1236, par.2.) 4. Involuntary novation by substitution of debtor. — By means of garnishment (see Art. 1243.), which is a species of attachment or execution for reaching any property pertaining to a judgment debtor which may be found owing to such a debtor by a third person, the latter, through service of the writ of garnishment, becomes a virtual party to, or a “forced intervenor’’ in the case. The court, having acquired jurisdiction over the person of the garnishee, requires him to pay his debt, not to his former creditor, but to the new creditor, who is creditor in the main litigation. Substitute must be placed in the same position of original debtor. In stating that another person must be substituted in lieu of the debtor, Article 1293 means that it is not enough to extend the juridical relation to that other person, but it is necessary to place the latter in the same position occupied by the original debtor who is released from the obligations. Effect where third person binds himself as principal with debtor. Since it is necessary that the third person should become a debtor in the same position as the debtor whom he substitutes, this change and the resulting novation may be with respect to the whole debt, thus releasing, as a general rule, the debtor from his obligation; or he may continue with the character of such debtor and also allow the third person to participate in the obligation. ART. 1294. If the substitution is without the knowledge or against the will of the debtor, the new debtor’s insolvency or non-fulfillment of the obligation shall not give rise to any liability on the part of the original debtor. (n) Because the substitution of the debtor is done without the knowledge or consent of the debtor. The substitution is without the consent or even just knowledge of the debtor, the inability of the new debtor to pay the obligation he has shouldered shall not in any way make the old debtor who is now freed from liability, much less must the original debtor be affected by insolvency of the new debtor in whose choosing the former never participated. Expromision – which the creditor accepts a new debtor, who becomes bound instead of the old the latter being released. ART. 1295. The insolvency of the new debtor, who has been proposed by the original debtor and accepted by the creditor, shall not revive the action of the latter against the original obligor, except when said insolvency was already existing and of public knowledge, or known to the debtor, when he delegated his debt. (1206a) Effect of new debtor’s insolvency or non-fulfillment of obligation. 1. In expromision. — Under Article 1294, the new debtor’s insolvency or nonfulfillment of the obligation will not revive the action of the creditor against the old debtor whose obligation is extinguished by the assumption of the debt by the new debtor. 2. In delegacion. — Article 1295 refers to delegacion. It must be noted that the article speaks only of insolvency. If the non-fulfillment of the obligation is due to other causes, the old debtor is not liable. The general rule is that the old debtor is not liable to the creditor in case of the insolvency of the new debtor. ART. 1296. When the principal obligation is extinguished in consequence of a novation, accessory obligations may subsist only insofar as they may benefit third persons who did not give their consent. (1207) Effect of novation on accessory obligations. The above article follows the general rule that the extinguishment of the principal obligation carries with it that of the accessory obligations. (see Arts. 1230, 1273, 1280.) ART. 1297. If the new obligation is void, the original one shall subsist, unless the parties intended that the former relation should be extinguished in any event. (n) Effect where the new obligation void. Article 1297 stresses one of the essential requirements of a novation, to wit: the new obligation must be valid. The general rule is that there is no novation if the new obligation is void and, therefore, the original one shall subsist for the reason that the second obligation being inexistent, it cannot extinguish or modify the first. To the rule is excepted the case where the parties intended that the old obligation should be extinguished in any event. Effect where the new obligation voidable. If the new obligation is only voidable, novation can take place. But the moment it is annulled, the novation must be considered as not having taken place, and the original one can be enforced, unless the intention of the parties is otherwise. ART. 1298. The novation is void if the original obligation was void, except when annulment may be claimed only by the debtor, or when ratification validates acts which are voidable. (1208a) Effect where the old obligation void or voidable. This article has its basis also on the requisites of a valid novation. A void obligation cannot be novated because there is nothing to novate. EXAMPLE: S agreed to deliver prohibited drugs to B. Later on, it was agreed that S would pay B P100,000.00 instead of delivering the drugs. The novation is void because the original obligation is void. ART. 1299. If the original obligation was subject to a suspensive or resolutory condition, the new obligation shall be under the same condition, unless it is otherwise stipulated. (n) Presumption where original obligation subject to a condition. If the first obligation is subject to a suspensive or resolutory condition, the second obligation is deemed subject to the same condition unless the contrary is stipulated by the parties in their contract. ART. 1300. Subrogation of a third person in the rights of the creditor is either legal or conventional. The former is not presumed, except in cases expressly mentioned in this Code; the latter must be clearly established in order that it may take effect.(1209a) Meaning of subrogation. Subrogation is the substitution of one person in the place of another with reference to a lawful claim or right, so that he who is substituted succeeds to the right of the other in relation to a debt or claim, including its remedies and securities. It contemplates full substitution such that it places the party subrogated in the shoes of the creditor, and he may use all means which the creditor could employ to enforce payment. A subrogee cannot succeed to a right not possessed by the subrogor. Kinds of subrogation. 1. Conventional 2. Legal Conventional subrogation must be clearly established in order that it may take place. Legal subrogation is not presumed except in the cases expressly provided by law. ART. 1301. Conventional subrogation of a third person requires the consent of the original parties and of the third person. (n) Consent of all parties required in conventional subrogation. (1) the debtor. — because he becomes liable under the new obligation to a new creditor. (2) the old or original creditor. — because his right against the debtor is extinguished. (3) the new creditor. — because he may dislike or distrust the debtor. Conventional subrogation and assignment of credit distinguished. Assignment of credit has been defined as the process of transferring the right of the assignor to the assignee who would then have the right to proceed against the debtor. ART. 1302. It is presumed that there is legal subrogation: (1) When a creditor pays another creditor who is preferred, even without the debtor’s knowledge; (2) When a third person, not interested in the obligation, pays with the express or tacit approval of the debtor; (3) When, even without the knowledge of the debtor, a person interested in the fulfillment of the obligation pays, without prejudice to the effects of confusion as to the latter’s share. (1210a) Cases of legal subrogation. (1) When a creditor pays another creditor who is preferred (2) When a third person without interest in the obligation pays with the approval of the debtor (3) When a third person with interest in the obligation pays even without the knowledge of the debtor ART. 1303. Subrogation transfers to the person subrogated the credit with all the rights thereto appertaining, either against the debtor or against third persons, be they guarantors or possessors of mortgages, subject to stipulation in a conventional subrogation. (1212a) Effect of legal subrogation. The effect of legal subrogation is to transfer to the new creditor the credit and all the rights and actions that could have been exercised by the former creditor either against the debtor or against third persons, be they guarantors or mortgagors. The effect of legal subrogation as provided in Article 1303 may not be modified by agreement. The effects of conventional subrogation are subject to the stipulation of the parties. There are distinctions between the right to be subrogated and the right to reimbursement. ART. 1304. A creditor, to whom partial payment has been made, may exercise his right for the remainder, and he shall be preferred to the person who has been subrogated in his place in virtue of the partial payment of the same credit. (1213) Effect of partial subrogation. The creditor to whom partial payment has been made by the new creditor remains a creditor to the extent of the balance of the debt. In case of insolvency of the debtor, he is given a preferential right under the above article to recover the remainder as against the new creditor. EXAMPLE: D is indebted to C for P10,000.00. X pays C P6,000.00 with the consent of D. There is here partial subrogation as to the amount of P6,000.00. D remains the creditor with respect to the balance of P4,000.00. Thus, two credits subsist. In case of insolvency of D, C is preferred to X, that is, he shall be paid from the assets of A ahead of X.