Technicians and Their Jobs: A Guide for Schools & Colleges

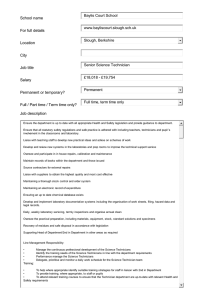

advertisement