Thomas N Duening Robert A Hisrich Michael A Lechter - Technology entrepreneurship taking innovation to the marketplace-Elsevier Science, Academic Press (2015)

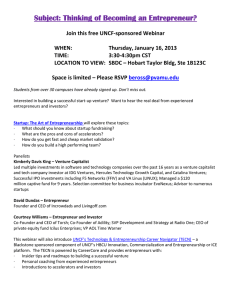

advertisement