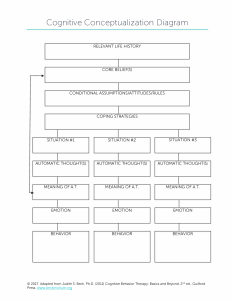

Emotion in learning: a neglected dynamic Christine Ingleton Advisory Centre for University Education University of Adelaide Learning environments are social environments, and learners are highly complex beings whose emotions interact with their learning in powerful ways. To value the learner is to value the whole person, not just the intellect. In this paper, a model of emotion in learning is developed which illustrates the role of emotion in establishing and maintaining identity and self-esteem in learning situations. From the standpoint of psycho-analytic and socialconstructionist theory, it is argued that the disposition to learn has its basis in social relationships. Arising from those relationships are the emotions of pride and shame which play a key role in the development of identity and self-esteem. The dynamics of pride and shame and identity, in the context of experiences of success and failure, may dispose students to act positively or negatively towards learning. The theory is illustrated in the experiences of students in mathematics classrooms from primary to tertiary level. These experiences indicate that emotion is constitutive of learning, and merits greater consideration in learning theory. Introduction It is surprising that the role of emotion in learning remains largely unexamined and certainly undervalued in the higher education literature, despite every-day experiences in which teachers are delighted or disappointed by the performance of students who surpass or fail to reach their intellectual potential. It appears that emotions can be powerful in encouraging and inhibiting effective learning and approaches to study, but educational research and models of learning have shed little light on the interrelationships between emotions and learning. Even theories of emotion have been accorded scant attention until recently (Barbalet 1998), due in no small part to the legacy of dualism which has opposed reason to emotion, and accorded reason the high status inscribed in Western thinking, and immortalised in Descartes’ statement, ‘I think, therefore I am’. This neglect is due in part to the domination of cognitive psychology over educational research until the past two decades, and the difficulty in capturing the emotional components of learning for research purposes. Educational research is now increasingly looking to the social sciences (for example Marton et al 1984) and socio-linguistics (Davies 1994) for frameworks with which to understand learning in its broader socio-cultural contexts. The constructionist paradigm is particularly useful in that it focuses on the meaning people make of their experience (for example, Entwistle 1983) and so affords opportunities to examine many aspects of experience, including emotion. Constructionists view ‘all knowledge…as contingent upon human practices, being constructed in and out of interaction between human beings and their world, and developed and transmitted within an essentially social context’ (Crotty 1998 p 42). Constructionism in learning is developed in the early work of Säljö (1979) and of Marton et al (1984), who demonstrated that students perceive their learning strategies to vary between situations, and that they employ deep and surface learning strategies according to their judgment of the situation. The current emphasis on student-centred learning and teaching is strongly underpinned by their work and is being developed using phenomenography (see, for example, Higher Education Research and Development June 1997 16: 2) to understand better how students construct knowledge and how teachers construct learning situations (Entwistle 1997). However, much of this work has concentrated on the exploration of conceptual understanding, and as Säljö (1997) argues, the interview methods and analysis used may actually limit the researchers’ access to HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 1 Ingleton students’ experiences of learning, including their emotional experience, by focusing on their perceptions of conceptual learning alone. In much of the phenomenographic literature, the dichotomy between cognition and emotion tends to be maintained, with cognition taking the foreground and emotion remaining in the background, largely unexamined. Emotion theory Recent work on the theory of emotion by sociologist J. M. Barbalet (1998) is useful in foregrounding the emotional context of learning. Barbalet points out that although there is no consensus in the literature defining ‘an emotion’, there is agreement that emotion includes three elements: ‘a subjective component of feelings, a physiological component of arousal, and a motor component of expressive gesture’ (Barbalet 1998 p 86). Significantly, he and others such as Scheff (1997) characterise emotion as comprising cognitive and dispositional elements. Emotion states include decision-making and a disposition to act, and so emotion has elements of reason and action as well as of feeling. Emotion can no longer be (dis)regarded as a synonym for irrationality. In the literature, the emotion of shame has become prominent in recent years (Frijda, 1994; Kitayama, 1994). Scheff (1991) describes shame as the ‘master emotion’, basic to the dynamics of relationships because of the way in which shame generates alienation while its opposite, pride, accompanies solidarity. He argues that shame is crucial in social interaction because it ties together the individual and social aspects of human activity as part and whole. As an emotion within individuals it plays a central role in consciousness of feeling and morality. But it also functions as signal of distance between persons, allowing us to regulate how far we are from others (pp 13, 14). Distance between persons in social settings - and this can be seen particularly in learning settings - is a strong indicator of acceptance and rejection by those one looks to for recognition, especially parents, teachers and peers. Shame generally accompanies distance, whether through one’s own conscience or distancing by others. Shame is a normal part of the process of social control (Scheff 1997 p 74) in families and the wider society, and is fundamental to control in classrooms and schooling. Shame and pride are significant in the classroom experiences which make learning possible (Ingleton 1994) as they are fundamental in the formation of confidence, anxiety and fear. Pride and shame are central in the construction of identity, and so are significant in the theorising of emotion and learning. Emotion and identity Scheff’s theory of the social bond (1997) provides a useful framework for relating identity, emotion and learning. Acceptance and recognition are key components in establishing pride, and are the basis of what Scheff calls the social bond. His theory of the social bond describes the social relationships of solidarity and alienation as basic to the development of identity and self-esteem. Or, to put it another way, self-esteem hinges on a cluster of ‘self-conscious emotions, particularly pride’ (Kitayama 1995 p 524). An application of this theory may be seen in Salzberger-Wittenberg’s account of her own tertiary students who were experienced school teachers returning to study. She analysed their emotional reactions on first entering their university classroom in terms of transference onto teachers of the early experiences of hope and fear, love and rejection, that they had experienced in relation to authority figures (Salzberger-Wittenberg et al 1983). The emotions central in early learning experiences were seen to continue actively into the present. If the social bond and self-esteem are high, one may be disposed to act HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 2 Emotion and learning with the confidence of positive expectation. This link between the social bond and confident expectation is a central element in the theory of emotion and learning proposed here. Emotion and learning Barbalet (1998) argues that confidence has a basis in particular experiences of social relationships – those situations in which a person receives acceptance and recognition. Conversely, anxiety and fear have their basis in situations in which a person is denied acceptance or recognition. Barbalet defines confidence as an emotion on the grounds that it includes the three elements: feelings, arousal and expressive gesture. Confidence functions in opposition to emotions such as anxiety, grief and dejection, emotions which may be accompanied by inactivity and isolation. And it functions in opposition to shame, shyness and modesty, which he describes as emotions of self-attention – ‘thinking what others think of us’ (p 86). Further, his theory of emotion proposes that confidence is the only emotion that has time as its object (Barbalet 1998). ‘All action’, he contends, ‘is based upon that confidence which apprehends a possible future’ (p 82). Confidence is the ‘affective basis of action and agency’ (p 88), for it foreshadows a willingness to act. Salzberger-Wittenberg (1983) contends that as learning arises in a situation in which we ‘do not as yet know’ or are ‘as yet unable to achieve what we aim to do’ (p 54), all learning invariably involves uncertainty, hope and fear. The possibility of acting or learning with confidence or a sense of certainty in the myriad moments of the unknowable future in the classroom springs from experiences of social relationships, both past and present. This may be modelled as follows: pride solidarity confidence social relationships disposition to learn shame distance fear Figure 1 Emotion and learning The model suggests relationships with teachers, peers and parents as giving rise to emotions of pride or shame. Accompanying these emotions are positions of solidarity or distance, attendant with confidence or fear. Together these are the basis of decisionmaking, conscious or unconscious, about immediate or future action. Action in this case refers to the disposition towards learning taken by an individual. This model is illustrated in the analysis below of students’ experiences of learning in mathematics classrooms. Methodology To explore specific examples of the relationship between confidence and learning, the methodology of Memory-work was chosen. This methodology, used in an earlier study of emotion and learning (Ingleton 1995), revealed the prevalence of pride and shame in the learning experiences of women, with shame being surprisingly pervasive. The findings were supported in a later study (Ingleton 1997) with groups of men and women learning economics, a study which also suggested gendered differences in emotional responses. The current study focuses on how confidence appears to be constructed in mathematics classrooms. The discipline of mathematics was chosen because students HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 3 Ingleton often report feeling strongly about mathematics, and difficulties are frequently reported by both students and staff in the learning and teaching of mathematics and statistics. Memory-work has been particularly successful in exploring the lived experience of individuals within the social relationships in which they ‘produce their lives’, in order to understand the social construction of aspects of self-identity (Haug 1987) and gender (Crawford et al 1992). In Memory-work, researchers make the assumption that what is remembered is significant, problematic, unfamiliar or in need of review (Crawford et al 1992, p 38). The theory underlying the methodology is that ‘memories are subjectively significant events which play an important part in the construction of self’ (Crawford et al 1992, p 37). A memory is seen as ‘a construction of a real event in time: a construction that changes with reflection over time’ (p 10). It is not the event which is important so much as the meaning that is negotiated in the remembering, the search for intelligibility in the construction of one’s life narrative. Through memories, past experiences are used to evaluate the present, and structure future actions. Memory-work involves working in a group in order to reflect the social production of experience. Memories, both spoken and written, are explored in a group, providing shared material from which participants and researchers together can reflect on and possibly reconstruct significant events. Spoken and written narratives are powerful ways of exploring meaning in past events. The ‘story or narrative provides the dominant frame for ... the organisation and patterning of lived experience’ (Epston 1992 p 80). ...Persons’ lives are shaped by the meaning they ascribe to their experience, by their situation in social structures, and by the language practices and cultural practices of the self and of relationship (p 122). Memory-work is a rich means of reconstructing experiences in order to understand the meanings they hold for persons in relationship to others in particular situations. Narratives are written in the third person to achieve some sense of distance, encourage the recall of detail, and to reduce the tendency towards autobiographical interpretation. Memory-work requires: the collection of written memories; collective analysis of these; reappraisal of the analysis in the context of theory. Rules for writing (Crawford 1992 p 45) are as follows: write a memory of a particular episode, action or event in the third person in as much detail as possible without importing interpretation, explanation or biography. Critical discourse analysis (Fairclough 1989) is the theoretical basis of the description, interpretation and explanation of the written narratives, as defined below. ‘Discourse’ refers to the concept of language as social practice determined by sets of conventions associated with social institutions (Fairclough p 17). The following approach to the analysis has been loosely based on Fairclough: description: how vocabulary and grammar are used to represent the writer’s experience; HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 4 Emotion and learning interpretation: how the activity, topic and purpose in the narrative describe the subjects of the story and their relationships; explanation: how social relationships and practices produce confidence and fear, based on the model of emotion and learning described in Figure 1. Any analysis of narrative is problematic in that a range of frameworks can be used for interpretation, with differing outcomes. The focus here is on how the contexts of the broader society, the institutional setting and the situational setting within that can affect emotional processes in specific learning situations. The purpose is to generate insight (Shotter 1993 p 34) to enable deeper understanding of emotion and learning in the light of the model that has been presented. Two groups met for the study. The members had chosen to participate after attending briefing sessions on the proposed study. Group One comprised six students undertaking a Graduate Diploma in Secondary Education, and intending to teach mathematics; Group Two comprised five university mathematics lecturers currently teaching mathematics. The groups each met twice to discuss the general topic of the study (introduced below) and to decide on themes for their written narratives. The narratives were written, read to the group, and discussed; the discussions were taped and transcribed. Of the twenty-one narratives written by the two groups, three are selected here to illustrate the centrality of emotion in learning, particularly the experience of pride, shame and confidence in learning. The three were chosen for gender balance and the inclusion of both positive and negative experiences. Another paper from the study (Ingleton and O’Regan 1998) focuses in more detail on the development of confidence in mathematics learning. The group discussions began with the following stimulus statement introduced by the researcher: ‘Maths is constructed as an objective, emotion-free discipline, yet the study of maths generates strong negative emotions among many learners.’ From the ensuing discussion, the students decided to write on the topics ‘Encouragement in learning mathematics’ and ‘Discouragement in learning mathematics’. The lecturers decided to use similar topics in order to enable a comparison of their experiences with the student group. The comparisons will appear in Ingleton and O’Regan (forthcoming). Experiences in mathematics learning The first narrative is written by Anne Marie (pseudonyms are used throughout) who has a BSc, and is training to teach mathematics at secondary level. Being encouraged in maths learning Anne-Marie Anne-Marie was in year 3 at a very small Catholic Primary school. She was seven years old, nearly a year younger than the other students in Year Three. Mrs Elton, the teacher, had designed a star system for times tables - you got tested at saying a particular times table (of your choice) and if you said it correctly, a coloured star would go on the chart under your name. For every fifth time you said a table correctly you got a silver star, and then every tenth time a gold and some House points. At the end of the week, House points were tallied up and the leading House announced at assembly. Every student had pride in their House and every student wanted to win, so it was a great feeling for Anne Marie to be able to cheer when the rest of her House came top. In the classroom, Anne-Marie practised her tables until she was confident at saying them with no mistakes and volunteered to be tested on them (this was the normal procedure). Butterflies would creep into her stomach and nervousness swept over her as she walked to the front of the class. The rest of the class were not interested in what Anne Marie was doing or whether Anne Marie passed, because they were preparing for their test. HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 5 Ingleton Once at the teacher's desk, Mrs Elton would ask Anne-Marie what table she was going to do today. 'Fours', Anne-Marie answered on this particular day. She'd been home the night before and interrupted her Mum's bath to be tested, and felt confident, except for the butterflies! 'OK, off you go', said Mrs Elton. 'Once four is four ... ,' recited Anne-Marie and got them all correct despite the shaky voice. 'Excellent, Anne-Marie!' exclaimed Mrs Elton. The praise brought a huge smile to Anne Marie's face and she beamed as the star was put up against her name. The introductory paragraph sets the scene for the memory. The broad framework is the social practice of compulsory primary schooling (ages five to twelve in Australia); the institutional setting that of a Catholic school in which the House system is practised as a means of organisation, co-operation, competition and control. Mathematics is important enough to be part of the weekly publication of House points. Specifically, the learning of tables is included in the star system - from coloured, silver, and gold to House points. Mathematics learning is highly valued in the society at large, and in the grade three classroom. It is a matter of public pride to win, and be part of the winning House. In this context, the learning of tables takes on the pride of winning and the fear of losing: ‘Butterflies would creep into her stomach and nervousness swept over her’. The opposing emotions of confidence and anxiety are alluded to again in the repetition of ‘confident’ and ‘butterflies’, then the ‘shaky voice’, until finally correctness is praised. Learning tables is a matter of winning or losing, despite the liberal approach of the teacher’s method. The children are allowed make choices - which times table to learn, and when to be tested. At this point, Mrs Elton does not appear to test; she accepts the child by listening. She builds a safe relationship and a supportive environment to develop confidence and pride in learning. At home, her mother supports Anne-Marie, in turn reinforcing the school ethos. First, Anne-Marie practises her performance with her mother, then with the confidence gained from this caregiver, she approaches the teacher, also her caregiver. ‘OK, off you go,’ the teacher says, and she is the only person to hear the tables being said; this test is private. Anne-Marie is rewarded by both her own internal judgment of readiness and the teacher’s ‘Excellent, Anne-Marie!’ Her ‘huge smile’ and an even bigger ‘beam’ accompany the public recognition of another star on her chart, as the House system reinforces the classroom practice. The structure of the narrative itself shows how Anne-Marie is positioned: the first paragraph describes the institutional organisation; the second her learning within that setting; the third the test, and the fourth the reward. The social organisation of the school, the House system, the classroom, the teacher’s practice, and the family place the individual in a learning climate of winning or losing, pride or shame. In winning, the solidarity with House, teacher and parent builds AnneMarie’s confidence to anticipate future success, through practice and volunteering to be tested again when ready. If one assumes that what is remembered is significant, that significance probably lies in the strength of the competing emotions in the anticipation of the possible outcomes, then the sheer pride of success and the teacher’s praise. Later, Colin’s narrative takes up the powerful theme of the shame of failure. The risk of being exposed as right or wrong to the teacher and whole class is everpresent in the classroom, but perhaps never as frequently as in mathematics classes, where one can be judged right or wrong every step of the way. In contrast to AnneMarie’s experience, humiliation or deliberate shaming characterises the following teacher, as the narrative by Stanley suggests. Stanley is currently undertaking a PhD and training to be a teacher of mathematics. HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 6 Emotion and learning Reward Stanley It was an early morning class, first lesson after the bell had gone in the morning. Stanley was in grade five and it was a warm day. The teacher was a loud man who would pressure people into getting answers or doing work by yelling and humiliating them. On this particular morning long division in maths was being taught and everyone in the class was having troubles. The teacher explained a few problems on the board before then picking on Stanley to go and do an example on the board. With everyone looking at him he solved the problem correctly and got the praise of the teacher rather than the humiliation that sometimes came with an incorrect answer. Stanley was then asked to try and explain problems and how to solve them to other students which brought a smile to his face as he enjoyed talking with the other students and helping them in their problems. The title ‘Reward’ belies the fear and tension underlying the relationship between Stanley and his teacher. The active subject in this narrative is the unnamed teacher who would exert pressure on his class by yelling, humiliating and picking on people. Stanley is an object, only taking the subject position when he solves the problem correctly. Then, he is the recipient of praise, but it could just as easily have been humiliation. It is as if he is in the background waiting for whichever response will befall him. Praise is paired with correctness, humiliation with incorrectness. Either will happen in public, ‘with everyone looking at him.’ In the final paragraph, the passive voice is used as he is asked to help other students. Stanley’s expression of feeling is muted; a smile comes to his face as he enjoys talking with the others. The relief from the earlier pressure is palpable. ‘Everyone in the class was having troubles’. In this pressured environment, students were being introduced to the concept and processes of long division. The learning itself is as emotional as it is intellectual. In front of the whole class Stanley’s self-esteem is at risk each time he displays his knowledge or ignorance. With everyone in the class having troubles, there is every chance of being wrong, especially when working on the board in front of the class with an unfamiliar concept. There is relief in winning approval, and recognition of his skills in being asked to help others in the class. Helping others with their mathematics, and being helped by others, is frequently mentioned in other narratives and discussions as a positive experience, particularly by the university teachers. Learning from each other strengthens bonds, and saves students from the threat of publicly displaying their ignorance. Later in the discussion following the reading of the narrative, Stanley comments, I think humiliation’s the worst. That is terrible. In a way here at uni it’s used to cull people out because you’ve got six hundred people in the class; what he’s going to ask is a way of getting rid of people, to see who are going to be good enough to go on, unfortunately. The same threat is there, years later at university. The ‘terrible’ feeling of humiliation in not measuring up to ‘what he’s going to ask’ is matched by the power of the culling metaphor. It appears to Stanley that the mathematics class is about getting rid of people. With classes so large, and questions so public, there is scant opportunity for solidarity as there was in primary school. The threat of shame and distance from both teacher and other students characterise his learning environment, disposing Stanley to feel anxious and fearful in this environment, just as he did in grade five. HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 7 Ingleton Long multiplication is the topic in the next mathematics classroom. Colin has an Honours degree and teaches mathematics at tertiary level in a student support role. Untitled Colin In year five of primary school when Colin was around ten years old, he had Mrs James, a rather highly strung teacher who always seemed on the verge of anger. Her method of teaching long multiplication involved setting a number of exercises on the board and leaving the final answers on a table at the front of the room. The kids worked alone and in silence while she did something else at her desk. Colin completed the problems but found on checking that every one was completely wrong with no clues as to why. Plucking up what little courage he possessed, he approached Mrs James' turned shoulder and mumbled, "I seem to have got these all wrong and I don't know why… ." The teacher turned from her work, glanced at the proffered calculations and exclaimed, "You stupid boy! Look at this!" while ringing one of them with angry red circles. "Now go back and do them properly!" Colin had to negotiate the walk back to his desk under the silent gaze of his classmates, still with no idea what had gone wrong. After a few minutes staring at the questions, he stole a glance at his deskmate's work and saw that he was putting the leading zeros in successive lines directly underneath the previous columns rather than creating new ones. It took Colin many years to realise that he wasn't a "stupid boy" and there may have been a problem with Mrs James' teaching style. The key subjects in this narrative are Colin, his teacher, her method of teaching and his classmates. His teacher’s anger features in the first sentence. The distance in her approach to teaching sets the scene of the classroom in the first paragraph. She sets exercises on the board, leaves the answers at the front, and does something else while the students work alone and in silence. In this environment, Colin discovers his answers are ‘completely wrong’. In order to learn, Colin has to risk her anger. He already lacks courage and now is confronted by her threatening ‘turned shoulder’. The risk is rewarded with humiliation - the exclamation of stupidity heard by all the class, the angry red circles on his work, and the refusal to help. The judgment ‘stupid boy’ is burned into his image of himself as a mathematics learner for years to come. Colin experiences alienation as he negotiates in shame the walk back to his desk under the silent gaze of the class. After reading the narrative, Colin said, I knew what the reaction was going to be but it was the only way to find out what was going wrong. The power relationship in the classroom is such that the students are supposed to speak to and learn from the teacher only. Conforming behaviour is attained through shaming and ‘its low-intensity forms of embarrassment and uneasiness’ (Frijda 1994 p 77). As a body, the class gazes silently at Colin, united in self-protection from her anger while Colin is isolated as the butt of her anger. ‘Negotiating’ the walk back to his desk suggests the need to make a deal or clear an obstacle, to deal with the humiliation and the problem of how to find answers. From eyes cast down on his work, he eventually looks sideways and ‘steals’ the help he needs from his neighbour. He has to steal in order to learn. He has to deal with humiliation in order to learn. Mrs James wields a high level of threat in this silent classroom, and is long-remembered for her attack on Colin. His disposition to learn is coloured by her label, ‘stupid boy’, a self-perception which remains with him for years to come: HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 8 Emotion and learning Colin: This incident stands out from a time in my life I remember very little about. Richard: You learnt from a stolen glance, not your teacher. Colin: Not from my teacher, yes. It took me years to realise that it wasn’t - -or he took years to realise that it wasn’t his fault on that occasion. Richard: He wasn’t a stupid boy. Colin: Yes. Sue: The angry red circles. Colin: Well that’s what they were. Sue: And the notions of courage and fault are very powerful. Chris: You really were into the lion’s den. Colin: It was yes, in front of everyone. Chris: Humiliation’s a very public thing, isn’t it, in the classroom? Colin: Especially when you’re shy. Emotion and learning Shame and pride are powerful emotions in learning because they are part of social bonding, and the basis of self-identity and self-esteem. Because they are part of identitybuilding, they are essential to the protection of self-esteem. In learning, one works hard at minimising risk, or avoiding risk, to avoid shame and the lowering of self-esteem. This may well be a significant basis of so-called maths anxiety (Ingleton and O’Regan 1998). Feick and Rhodewalt (1997) discuss how uncertainty about one’s ability leads people to ‘self-handicap’, to not do well, or not try, for example, in order to discount the effect of failure, in the service of maintaining self-esteem. In order to maintain a sense of solidarity and acceptance, some students will deliberately not value academic success, or females will not do well if success in a given area is not valued as gender-appropriate, again to maintain their self-identity (Ingleton 1994). The classroom is the site of constant social interaction centering on approval and disapproval for being right and being wrong. Such judgments appear to be particularly frequent and public in the mathematics classroom, perhaps more so than for any other subject. These judgments appear to be largely associated with the absolute correctness or incorrectness of performance, and are generally experienced from the age of seven years for most students. However, emotion plays a powerful role in learning in any subject, at any age and ability level, and for any learner. Conclusion Emotion is often considered as merely the affective product of learning, but by theorising emotion as being formed in social relationship and significant in the development and maintenance of identity, its role in learning is constructed at a much deeper level. As such, emotion is seen to be constitutive of the activity of learning. Past emotions and memories may be experienced consciously or unconsciously in the present, and are ongoing in the maintenance of self-esteem and identity. More than the product of individual personalities and experiences, they are constitutive of social settings that comprise interpersonal relationships of power and control in institutional settings. Emotions shape learning and teaching experiences for both teachers and students, and the recognition of their significance merits further consideration in both learning theory and pedagogical practice. HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 9 Ingleton References Barbalet, J. (1998). Emotion, Social Theory and Social Structure. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Crawford, J., Kippax, S., Onyx, J., Goult, U., Benton, P. (1992). Emotion and Gender: Constructing Meaning from Memory. London, SAGE. Crotty, M. (1998). The Foundations of Social Research. Sydney, Allen and Unwin. Davies, B. (1994). Poststructuralist Theory and Classroom Practice. Geelong, Deakin University. Entwistle, N. (1997). “Introduction: Phenomenography in Higher Education.” Higher Education Research and Development 16(2): 127-134. Entwistle, N. and Ramsden., P. (1983). Understanding Student Learning. London, Croom Helm. Epston, D. and White, M. (1992). Experience, Contradiction, Narrative and Imagination: Selected papers of David Epston and Michael White, 1989 - 1991. Adelaide, Dulwich Centre Publications. Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and Power. New York, Longman. Frijda, N. H.and Mesquita, B. (1994). The social roles and functions of emotions. Emotion and Culture. S. Kitayama, and Markus H.R. Washington DC, American Psychological Association. Haug, F., Ed. (1987). Female Sexualization. A Collective Work of Memory. London, Verso. Ingleton (1994). “Gender, Emotion and Learning.” Unpublished Thesis Geelong, Deakin University. Ingleton, C. (1995). “Gender and learning: Does emotion make a difference?” Higher Education 30: 323-335. Ingleton, C. (1997). “Factors Contributing to Lower Participation of Women in the Study of economics in Australia: An Exploratory Study.” Australian Economic Papers (Special Issue September): 46-55. Ingleton, C. and O’Regan. K. (1998). “Recounting mathematical experiences: exploring the development of confidence in mathematics.” Paper presented at AARE Conference, Adelaide, December. Kitayama, S., and Markus H.R. (Ed.). (1994). Emotion and Culture. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Kitayama, S., Markus, H.R., and Lieberman, C. (1995). The Collective Construction of Self Esteem. Implications for Culture, Self and Emotion. Everyday Conceptions of Emotion. J. A. Russell, Fernandez-Dols, J-M., Manstead, A.S.R., and Wellenkamp, J.C., NATO Advanced Science Institutes. HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 10 Emotion and learning Marton, F. H., Hounsell, D. & Entwistle, N.J., Ed. (1984). The Experience of Learning. Edinburgh, Scottish Academic Press. Säljö, R. (1979). Learning in the Learner's Perspective. Considering one's own strategy. Goteborg, Institute of Education, University of Goteborg. Säljö, R. (1997). “Talk as Data and Practice.” Higher Education Research and Development 16(2): 173-190. Salzberger-Wittenberg, I. Henry, G. and Osborne, E. (1983). The emotional experience of learning and teaching. London, Routledge and Kegan Paul. Scheff, T. J. (1997). Emotions, the social bond and human reality. Cambridge, Scheff, T. J. and Retzinger, M. (1991). Emotions and Violence. Massachusetts. Lexington Books. Shotter, J. (1993). Conversational realities: Constructing life through language. London, SAGE. HERDSA Annual International Conference, Melbourne, 12-15 July 1999 11