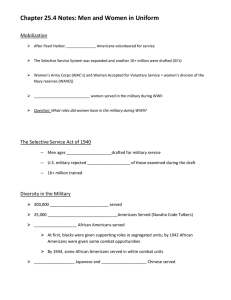

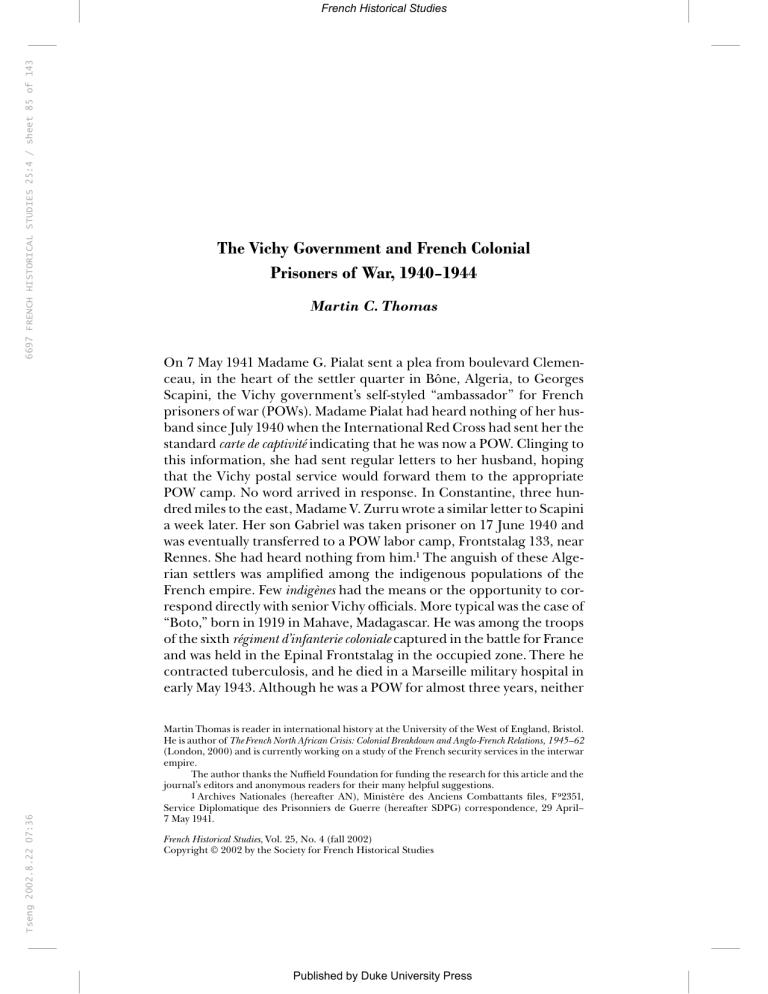

Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 85 of 143 French Historical Studies The Vichy Government and French Colonial Prisoners of War, 1940–1944 Martin C. Thomas On 7 May 1941 Madame G. Pialat sent a plea from boulevard Clemenceau, in the heart of the settler quarter in Bône, Algeria, to Georges Scapini, the Vichy government’s self-styled ‘‘ambassador’’ for French prisoners of war (POWs). Madame Pialat had heard nothing of her husband since July 1940 when the International Red Cross had sent her the standard carte de captivité indicating that he was now a POW. Clinging to this information, she had sent regular letters to her husband, hoping that the Vichy postal service would forward them to the appropriate POW camp. No word arrived in response. In Constantine, three hundred miles to the east, Madame V. Zurru wrote a similar letter to Scapini a week later. Her son Gabriel was taken prisoner on 17 June 1940 and was eventually transferred to a POW labor camp, Frontstalag 133, near Rennes. She had heard nothing from him.1 The anguish of these Algerian settlers was amplified among the indigenous populations of the French empire. Few indigènes had the means or the opportunity to correspond directly with senior Vichy officials. More typical was the case of ‘‘Boto,’’ born in 1919 in Mahave, Madagascar. He was among the troops of the sixth régiment d’infanterie coloniale captured in the battle for France and was held in the Epinal Frontstalag in the occupied zone. There he contracted tuberculosis, and he died in a Marseille military hospital in early May 1943. Although he was a POW for almost three years, neither Martin Thomas is reader in international history at the University of the West of England, Bristol. He is author of The French North African Crisis: Colonial Breakdown and Anglo-French Relations, 1945–62 (London, 2000) and is currently working on a study of the French security services in the interwar empire. The author thanks the Nuffield Foundation for funding the research for this article and the journal’s editors and anonymous readers for their many helpful suggestions. 1 Archives Nationales (hereafter AN), Ministère des Anciens Combattants files, F 92351, Service Diplomatique des Prisonniers de Guerre (hereafter SDPG) correspondence, 29 April– 7 May 1941. French Historical Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4 (fall 2002) Copyright © 2002 by the Society for French Historical Studies Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 86 of 143 French Historical Studies 658 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES the Frontstalag authorities nor the Vichy military bureaucracy had any record of his relatives or his entitlements.2 These episodes suggest that although the release and repatriation of French POWs was critically important to the Vichy state, the fate of colonial prisoners of war was a different matter. French colonial POWs suffered more than their metropolitan counterparts from the vicissitudes of Vichy politics. The Vichy regime adopted a racialist worldview, as its existence was predicated first on coexistence, then on collaboration, with the Nazi racial order. Vichy colonial policies rested on a systematic categorization of racial difference, both between the French and their colonial populations and among the indigenous peoples themselves.3 Captured colonial troops were supposedly the living embodiment of undying loyalty to the French empire. In practice, they were doubly confined, at once prisoners of the Nazis and beholden to Vichy’s conception of racial hierarchy within the overseas empire. The Vichy construct of racial order was a very blunt instrument as far as colonial POWs were concerned. Policy toward colonial prisoners was increasingly determined by which territories remained under Vichy control. The declining fortunes of the Vichy empire had three principal consequences for colonial POWs. First, after June 1940 French North Africa’s place at the top of the French imperial system was clearer than ever, a consideration that sharpened Vichy’s primary focus on Maghrebi (North African) prisoners, to the exclusion of their colonial brethren. Second, between 1940 and 1942, the gradual erosion of Vichy authority in black Africa, Madagascar, and, to a lesser degree, Indochina and the French Antilles, reinforced the tendency among Vichy officials to treat POWs from these territories as inferior to those from North Africa.4 Third, these Maghrebi prisoners became pawns in the propaganda contest between the Vichy government and the Nazi authorities to sway the allegiance of the Muslim population in North Africa. In sum, Vichy efforts to safeguard colonial POWs were pathetically ineffective. Vichy’s policy priorities were governed by a combination of racial stereotyping, imperial expediency, and uneasy colonial Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 2 AN, F 92966, no. 48764/ RC/ PG, General Bridoux to Bléhaut, 20 July 1943. 3 Pascal Blanchard and Gilles Boëtsch, ‘‘Races et propagande coloniale sous le régime de Vichy, 1940–1944,’’ Africa 49 (1994): 531–61; Eric T. Jennings, Vichy in the Tropics: Pétain’s National Revolution in Madagascar, Guadeloupe, and Indochina, 1940–1944 (Stanford, Calif., 2001), 22–28, 40– 41. Throughout this article the term colonial will be used to designate all prisoners indigenous to French overseas territories, including French North Africa and the Syrian Mandate. It should be noted that in official terminology North African and Syrian troops were always separately described. 4 Eric Jennings provides an outstanding treatment of Vichy colonial rule in Madagascar, Indochina, and Guadeloupe in his Vichy in the Tropics. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 87 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 659 collaboration with Nazi Germany. It was impossible to reconcile an explicitly articulated racialism with the attempt to conserve the loyalty of captured colonial soldiers, and rivalry with Germany for Maghrebi prisoners’ allegiance made this contradiction obvious. French colonialism had long been constructed on theories of racial difference and the alleged connection between race and particular forms of social organization.5 In the Third Republic, parti colonial imperialists and liberal colonial reformers applied the social Darwinian concept of a ‘‘struggle for life’’ among races to justify French colonial rule. The parti colonial imperialists explicitly championed the superiority of French racial stock. The colonial reformers insisted that French cultural practices and humanist values would bring peace and progress to backward colonial populations.6 The history of French colonialism constructed during the interwar period and transmitted to the general public in school texts, media representation, and popular imperialist imagery was both ethnocentric and racially ordered.7 Republican values persisted, albeit largely rhetorically, in the attendant portrayal of empire as a rational and mutually beneficial enterprise. Vichy was new in what Miranda Pollard identifies in the context of gender as its ‘‘radically nostalgic agenda’’—Catholic, patriarchal, and pre-modernist.8 Prewar France had been moving toward the justification of empire by its social and material transformation of overseas territories. Yet, in the same period, the economic exploitation of colonial populations intensified, and precious few envisaged reforms, most notably those of the Popular Front, were ever fully enacted. The application of Vichy authoritarianism to colonial settings certainly did not require outright reversal of previous administrative methods. Nonetheless, the vigor with which Vichy imposed racially determined policies in the colonial empire is striking. The regime passed a welter of colonial legislation to regulate relations between the rulers and the ruled. The sûreté générale and Vichy’s military intelligence and counterespionage bureaus monitored con5 See, for example, Raymond Betts, Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890–1914 (New York, 1961); Patricia M. E. Lorcin, Imperial Identities: Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Race in Colonial Algeria (New York, 1995); Michael G. Vann, ‘‘The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Variation and Difference in French Racism in Colonial Indochina,’’ in Proceedings of the Western Society for French History, vol. 25, ed. Barry Rothaus (Denver, Colo., 1998), 11–23. 6 Jean-Marc Bernardini, Le darwinisme social en France (1859–1918) (Paris, 1997), 184–95; Gary Wilder, ‘‘The Politics of Failure: Historicizing Popular Front Colonial Policy in French West Africa,’’ in French Colonial Empire and the Popular Front, ed. Tony Chafer and Amanda Sackur (London, 1999), 34–46. 7 Eric Savarese, L’ordre colonial et sa légitimation en France métropolitaine (Paris, 1998), 175–206. 8 Miranda Pollard, Reign of Virtue: Mobilizing Gender in Vichy France (Chicago, 1996), 56. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 88 of 143 French Historical Studies 660 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES tacts between civilian populations and the colonial servicemen of the armistice armies.9 In Vichy Africa colonial ex-servicemen’s associations, such as the Légion Française des Combattants de l’Afrique Noire, provided an additional means to control political activity.10 The authoritarian precepts of the Révolution Nationale were readily adaptable to an environment of colonial exploitation, and Pétainist support was strongly rooted in the settler communities of North Africa and Vietnam in particular. In overseas territories far removed from the terrain of defeat and occupation, Vichyite administrations had freer rein to idealize French military tradition, not least the achievements of imperial conquest in which colonial troops had often played a central part. Empire was supposedly Vichy’s greatest remaining strategic and economic asset. This was a message taken up by the Ligue Maritime et Coloniale, successor to the Parti Colonial, whose journal, Mer et colonies, was even distributed to metropolitan POWs in German stalags.11 Could the thousands of colonial POWs simply be written out of Vichy’s empire propaganda and its new imperial mission? After the fall of France, close to 4 percent of the country’s population faced life in German captivity. Tens of thousands of French colonial troops were also taken prisoner, but their needs were eclipsed by those of the 1.5 million metropolitan POWs held in Germany. A core objective of Vichy POW policy was to secure the allegiance of the mass of metropolitan French prisoners and their dependents. The right to introduce Révolution Nationale propaganda alongside the food and clothing parcels delivered to French POWs in Germany was a prized concession.12 Official unease about the POWs’ eventual reintegration into French civilian life bolstered efforts to prevent their political alienation from metropolitan France. The Free French were no less unnerved about POW loyalties. In the bitter propaganda war between Vichy and Free France, allegations of military abandonment and colonial treachery were widespread.13 From its inception in October 1941, 9 Surveillance records are in the ‘‘Archives de Moscou’’ collection of French military intelligence papers repatriated from Russia to France in 1994 and now housed in the Service Historique de l’Armée (hereafter SHA) archive at Vincennes. 10 James L. Giblin, ‘‘A Colonial State in Crisis: Vichy Administration in French West Africa,’’ Africana Journal 5 (1994): 334–35. 11 Charles-Robert Ageron, ‘‘Vichy, les Français et l’empire,’’ in Vichy et les français, ed. JeanPierre Azéma and François Bédarida (Paris, 1992), 122–29. 12 Pieter Lagrou, The Legacy of Nazi Occupation: Patriotic Memory and National Recovery in Western Europe, 1945–1965 (Cambridge, 2000), 106–7. For detailed analysis of French POW families and government return policy, see Sarah Fishman, We Will Wait: The Wives of French Prisoners of War, 1940–1945 (Cambridge, Mass., 1991); Christophe Lewin, Le retour des prisonniers de guerre français (Paris, 1986); François Cochet, Les exclus de la victoire: Histoire des prisonniers de guerre, déportés et STO (Paris, 1992). 13 Pascal Blanchard and Gilles Boëtsch, ‘‘La France de Pétain et l’Afrique: Images et propa- Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 89 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 661 Vichy’s Commission for the Reintegration of Prisoners of War devised reception and welfare programs intended to prevent returning POWs from posing any threat to the state. After the liberation Henri Frénay’s Commission for Prisoners, Deportees, and Refugees remained fearful that POWs and labor conscripts would return from Germany hostile to the new republicanism and psychologically unprepared for the challenges of reconstruction.14 The colonial parallels are clear. Throughout the empire political rights were racially determined and narrowly confined. Even if not actively seditious, POW returnees with firsthand experience of France’s national humiliation and with the accumulated grievances of prolonged incarceration were inevitably a source of instability. Unlike their metropolitan counterparts, the colonial servicemen have received minimal attention in the historiography of France’s POWs, Vichy military policy, and French imperialism.15 Myron Echenberg highlighted this omission in 1985 and has since done much to correct it.16 His work has focused on West African soldiers and was produced before the papers of Vichy’s Ministère des Anciens Combattants and those of its military intelligence service became available. It is an easier task to shed light on governmental POW policies than to bring the prisoners themselves out of the shadows. Compared with their metropolitan counterparts, the censorship records detailing letters sent between colonial POWs and their loved ones are relatively sparse. Higher rates of illiteracy among colonial troops add to the problem. Myron Echenberg and Nancy Lawler stand out in their use of oral testimony to recreate the POW experience of West African tirailleurs from initial capture to eventual return home. German use of colonial POWs as a reservoir of forced labor in occupied France also invites comgandes coloniales,’’ Canadian Journal of African Studies 28 (1994): 1–31; Ruth Ginio, ‘‘Marshal Pétain Spoke to Schoolchildren: Vichy Propaganda in French West Africa, 1940–1943,’’ International Journal of African Historical Studies 33 (2000): 295–96, 302–6. 14 Lagrou, The Legacy of Nazi Occupation, 108–26. 15 Key texts on French POWs are Yves Durand, La captivité: Histoire des prisonniers de guerre français, 1939–1945 (Paris, 1980); Pierre Gascar, Histoire de la captivité des français en Allemagne (Paris, 1967). Essential treatments of specific aspects of prisoner life and POW families include Sarah Fishman, We Will Wait, and her ‘‘Waiting for the Captive Sons of France: Prisoner of War Wives, 1940–1945,’’ in Behind the Lines: Gender and the Two World Wars, ed. Margaret Randolph Higonnet, Jane Jenson, Sonya Michel, and Margaret Collins Weitz (New Haven, Conn., 1987); Lewin, Le Retour; André Durand, History of the International Committee of the Red Cross from Sarajevo to Hiroshima (Geneva, 1984); Jean-Marie d’Hoop, ‘‘Propagande et attitudes politiques dans les camps de prisonniers: Le cas des oflags,’’ Revue d’histoire de la deuxième guerre mondiale 122 (1981): 3–26; d’Hoop, ‘‘Prisonniers de guerre français: Témoins de la défaite allemande,’’ Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains 38 (1988): 77–98. 16 See his ‘‘‘Morts pour la France’: The African Soldier in France during the Second World War,’’ Journal of African History 26 (1985): 363–80, and his Colonial Conscripts: The Tirailleurs Sénégalais in French West Africa, 1857–1960 (Portsmouth, N.H., 1991). Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 90 of 143 French Historical Studies 662 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES parison with the coercive aspects of the colonial labor market in francophone black Africa before and during the Second World War, and historians of decolonization have long seen links between the politicization of colonial POWs and the resurgence of anticolonial protest in the immediate postwar years.17 Significant gaps remain in the historical treatment of France’s colonial POWs. North African prisoners, the largest group in this POW population, have been little studied.18 Neither have the links between Vichy propaganda and Nazi attempts to indoctrinate their Maghrebi detainees been much explored. Above all, the conditions and tensions of life inside the Frontstalags and the racial factors that shaped official thinking about colonial prisoners, primarily in relation to welfare policy and healthcare provision, have not been investigated in any detail. This article attempts a preliminary survey of these issues. French archives offer rich pickings here. Starting in July 1940, senior Vichy officials monitored the treatment, political indoctrination, and eventual release of colonial prisoners, principally North and West African infantrymen. Vichyite colonial governments could not ignore indigène grievances about absent loved ones. When colonial troops eventually returned home, their experiences in captivity, as well as their treatment after demobilization, were sure to affect their political outlook and that of their close relations. Rita Headrick has suggested five key determinants of attitude formation among colonial soldiers: recollections of combat, prolonged inactivity (and the consequent erosion of military discipline), the incidence of racial discrimination in conditions of long-term confinement, interaction with other colonial populations, and the detribalizing effects of prolonged absence.19 As we shall see, these factors resonated with the French colonial prisoner of war. However, it would be too reductive to state that ex-POWs formed a deracinated caste, alienated from their cultural roots by the long exile of military service and captivity. What does seem clear is that the collective experience of imprisonment under Nazi control induced a revaluation of French colonial authority. The conclusions drawn by veteran POWs 17 The fullest treatment of a distinct group of colonial POWs is Nancy Ellen Lawler, Soldiers of Misfortune: Ivoirien Tirailleurs of World War II (Athens, Ohio, 1992), chap. 5. See also Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts; Frederick Cooper, Decolonization and African Society: The Labor Question in French and British Africa (Cambridge, 1996); and two collections edited by Prosser Gifford and William Roger Louis: The Transfer of Power in Africa: Decolonization, 1940–1960 (New Haven, Conn., 1982) and Decolonization and African Independence: The Transfers of Power, 1960–1980 (New Haven, Conn., 1988). 18 Belkacem Recham, Les musulmans algériens dans l’armée française (1919–1945) (Paris, 1996), devotes a single chapter to Algerian POWs. 19 Rita Headrick, ‘‘African Soldiers in World War II,’’ Armed Forces and Society 4 (1978): 512–13. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 91 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 663 may be deduced from the large numbers of ex-servicemen intimately involved in anti-French political activity after 1945. Capture and Initial Release Efforts The French army that attempted to stem the German tide in May and June 1940 included ten divisions of colonial troops, some seventythree thousand men—almost 9 percent of the army deployed in France. Thousands more that had been posted throughout the empire faced an uncertain economic future after demobilization. In Algeria alone, 61,580 indigène troops were demobilized by September 1940. Their reintegration into the Algerian economy was deeply disruptive. Commercial employers, attracted by the cheaper wages for women war workers, were reluctant to reemploy ex-servicemen. Former agricultural laborers often refused to return to rural communes, adding to the emerging industrial underclass in the colony’s coastal cities. The impact of returning POWs would be greater still. Their expectations of preferential treatment were raised by wide-ranging Vichy legislation to protect the jobs and status of metropolitan prisoners, largely at women’s expense.20 Colonial soldiers’ military contributions demanded recognition. Colonial units were to the fore of initial engagements on the Aisne, the Somme, and in the Argonne forest near Montmédy in late May 1940. Three colonial infantry divisions suffered particularly heavy casualties before surrendering on 22 and 23 June 1940. In February 1942 the Vichy secretariat of war calculated the loss of colonial troops, including Moroccan regiments, during the battle for France as 4,439 killed and 11,504 missing and presumed dead. An additional 25,516 were confirmed as prisoners of war, a figure that significantly underestimated the total number of colonial troops taken captive in 1940.21 The widespread contempt with which French First World War veterans looked upon the brief combat experience of the 1940 POW generation was not reflected in the empire.22 Contemporary German and later African veterans’ accounts confirm that colonial units fought tenaciously. Both sources indicate that 20 SHA, Fonds privés, Papiers Général de Coislard de Monsabert, 1K380/C4, Rapport de l’office de démobilisation, Alger, 2 Sept. 1940. 21 SHA, Carton 15H142, dossier: ‘‘Participation des troupes coloniales à la campagne 1939– 1940,’’ 1 Feb. 1942. Eager to prove Aryan supremacy, German newsreel footage from June 1940 stressed the high proportion of colonial troops in captured French infantry units. These images were included in the 1971 Studio Saint-Séverin production, Le chagrin et la pitié. See Marcel Ophuls’s description of the film, Le chagrin et la pitié (Paris, 1980), 36. 22 To the annoyance of numerous 1914–18 veterans, as minister for veterans and war victims in 1947, François Mitterrand dropped the requirement for three months combat experience for ex-servicemen and deportees to qualify for the carte du combattant that confirmed ancien combattant status. See Lagrou, The Legacy of Nazi Occupation, 42–44. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 92 of 143 French Historical Studies 664 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES black troops were treated harshly upon capture. Cases of summary executions of black troops were soon reported.23 Surviving French colonial forces taken prisoner by the Wehrmacht were transported to temporary detention centers in Germany, northeastern France, and the Netherlands. Here the cruelties continued.Transit center guards were typically a mix of raw German recruits and French-speaking Alsatians newly conscripted into the Wehrmacht. Both groups were singled out in later POW debrief reports as exceptionally brutal. Accusations that colonial troops had tortured German soldiers and mutilated corpses were cited as justification for executions and random beatings. These abuses diminished only when most colonial POWs were reassigned to Frontstalags in occupied France. After June 1941 camps were increasingly staffed by German reservists considered too elderly for the eastern front and by conscripts from other annexed territories, mostly Austrians. Most prisoners appear to have found these guards more humane.24 The empire faced a worsening economic crisis after France’s defeat. The colonial export sector was distorted by urgent metropolitan needs and growing Axis demands. The loss of markets in the Englishspeaking world was worsened by the inability to conduct maritime trade elsewhere, owing to the British economic blockade of Vichyite territories. Officials in Dakar cast envious glances at the allied purchase program in Gaullist equatorial Africa. The very survival of the Indochina federation rested on Japanese forbearance, a factor that encouraged the ardent Vichyism of its governor-general, Admiral Jean Decoux.25 For black African workers in Vichyite West Africa, forced labor, starvation wages, and widespread shortages were powerful inducements to flee into neighboring British territories. The tradition of African migration to evade the burdens of military conscription and forced labor helps explain why Vichy officials discouraged escape attempts by colonial POWs.26 For colonial servicemen, escape from detention also im23 Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts, 88, 92–94; Lawler, Soldiers of Misfortune, 79–88, 94–96. As a young conscript, the Senegalese statesman Léopold Sédar Senghor only narrowly escaped execution on capture thanks to the intervention of a French officer; see Janet G. Vaillant, Black, French, and African: A Life of Léopold Sédar Senghor (Cambridge, Mass., 1990), 166–67. 24 SHA, Archives de Moscou, C24/ D1749, EMA-2, Section des affaires musulmanes, ‘‘L’action allemande auprès des prisonniers musulmans nord-africains,’’ n.d., 1942. 25 Christine Levisse-Touzé, L’Afrique du nord dans la guerre, 1939–1945 (Paris, 1998), 186– 96; Martin Thomas, The French Empire at War, 1940–45 (Manchester, U.K., 1998), 70–91, 195–201; Pierre Lamant, ‘‘La révolution nationale dans l’Indochine de l’Amiral Decoux,’’ Revue d’histoire de la deuxième guerre mondiale 138 (1985): 21–41. 26 The connections between military obligation, forced labor, and unauthorized migration are explored in A. I. Asiwaju, ‘‘Migrations As Revolt: The Example of the Ivory Coast and the Upper Volta before 1945,’’ Journal of African History 18 (1976): 577–94; Myron J. Echenberg, ‘‘Les migrations militaires en Afrique occidentale française, 1900–1945,’’ Canadian Journal of African Studies 14 (1980): 429–50; Babacar Fall, Le travail forcé en Afrique-occidentale française (1900–1946) Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 93 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 665 plied freedom from military and colonial obligation. The contraction of the colonial economy and the political implications of unsupervised freedom for former colonial POWs made their release still less of a priority. Vichy’s resumption of protecting powers for French citizens and colonial subjects on 16 November 1940 paved the way for representatives of Scapini’s Service Diplomatique des Prisonniers de Guerre (SDPG) to conduct inspections of POW camps. Parallel discussions began between the French mayoral authorities and the German military administration regarding camps in the occupied zone.27 The first Laval government cast Vichy’s role as protector of the POW population in a positive light, but it raised a fundamental problem. Scrutiny of POW treatment and camp conditions relied in practice on neutral intermediaries armed with inspection powers laid down by the Geneva Convention. French prisoners could still expect the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to monitor their welfare, but such was the importance of POW issues to the cultivation of Pétainism that the regime arrogated inspection powers to the SDPG.28 Here was what Sarah Fishman has tellingly defined as an ‘‘unintended consequence’’ of Vichy POW propaganda.29 Vichy officials ignored the conflict of interest inherent in their dual role as neutral observers and protagonists for French POWs. The fact that Vichy had no German prisoners who could be used to guarantee fair treatment of French captives increased the dilemma. Behind the increasingly worthless facade of the Geneva Convention, the surest safeguard of western European POW populations was the ability to take reprisal action against enemy prisoners.30 If French prisoners were mistreated, Vichy relied primarily on camp inspections rather than ordering punishment of a German POW population to secure redress. This too was a double-edged sword. The SDPG enjoyed a unique advantage in its ability to conduct frequent camp visits inside the Reich (Paris, 1993); Nancy Lawler, ‘‘The Crossing of the Gyaman to the Cross of Lorraine: Wartime Politics in West Africa, 1941–1942,’’ African Affairs 96 (1997): 53–71. 27 AN, F 92001/ D3, no. 965/40, Commission Allemande d’Armistice (CAA), Francösische abordnung bei der deutschen fenstillstandskommission, list of decisions, 14 Jan. 1941. 28 Jonathan F. Vance, ‘‘The Politics of Camp Life: The Bargaining Process in Two German Prison Camps,’’ War and Society 10 (1992): 109–10. In theory, the protecting power monitored captors’ observance of the Geneva Convention while the International Committee of the Red Cross remained an independent humanitarian agency. 29 Sarah Fishman, ‘‘Grand Delusions: The Unintended Consequences of Vichy France’s Prisoner of War Propaganda,’’ Journal of Contemporary History 26 (1991): 229–30. As Fishman emphasizes, the cult of Pétain as French savior demanded that POWs be kept in the Vichy media spotlight. 30 S. P. MacKenzie, ‘‘The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II,’’ Journal of Modern History 66 (1994): 489–91, 499–500. Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 94 of 143 French Historical Studies 666 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES and the occupied zone, but the inspection system had limitations. With their visits typically announced long in advance, inspectors rarely witnessed an accurate representation of prisoner conditions. Camps were artificially spruced up, interviews with individual prisoners were kept to a minimum, and the prompt redress of POW grievances was rendered impossible by complex bureaucratic procedure. In the weeks following the armistice, General Charles Huntziger’s delegation to the Wiesbaden Armistice Commission pressed for substantial POW releases. Huntziger’s negotiators singled out reservists over forty-five-years-old, sons whose fathers had been killed during the Great War, and, most important numerically, fathers or elder brothers with four or more dependent relatives.31 The one concession wrung from Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel was the so-called Berlin Protocol of 16 November 1940. It picked up an earlier French proposal for the release of POWs with large families and was the first release initiative that promised much for colonial prisoners. The colonial ministry’s prisoners of war division in Paris judged that in several camps up to 60 percent of indigène POWs had at least four children. Ministry staff concluded that ten thousand colonial POWs might thus be eligible for early release.32 In fact, the protocol was not applied equally to colonial troops. This caused understandable resentment among POWs. Anger among colonial prisoners increased following an official announcement on 2 July 1941 that all ‘‘white race’’ POWs held in France were to be released.33 On 12 September 1941 Minister of Colonies Charles Platon warned his fellow admiral, François Darlan, then deputy premier, that colonial POWs were a political tinderbox. Allegations of unfair treatment, racial discrimination, and abandonment by the Vichy regime were common. If these prisoners became more profoundly alienated, they might destabilize the colonial order on their return home. The prospect of another freezing winter only added to their despair.34 Were the POWs’ allegations justified? Treatment and Surveillance Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 Colonial troops had not figured as a distinct category in the initial Franco-German discussions of POW releases, but the Nazi government 31 AN, F 92001/2 dossier, no. 166/40, CAA Section Prisonniers de Guerre to French delegation, 11 Sept. 1940; AN, F 92002, no. 76/ PG and no. 704/ PG Sous-Commission des Prisonniers de Guerre, notes for General von Stülpnagel, 3 and 17 July 1940. 32 AN, F 92351, M. Stupfler, Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (Paris) to Dr. Bonnaud, 15 Nov. 1941. 33 SHA, 2P85/ D1, no. 12500, ‘‘Note au sujet de la libération de prisonniers indigènes et nord-africains,’’ 7 July 1941. 34 SHA, 2P85/ D1, no. 816/CAB/ PG, Platon to Darlan, 12 Sept. 1941. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 95 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 667 readily agreed to transfer colonial prisoners from transit centers in Germany to labor camps in the occupied zone. There was insufficient accommodation in Germany to house the massive numbers of POWs taken in May and June 1940. Racialist ideology and the abiding myth of brutal colonial troops (particularly Moroccan regiments) within the Rhine occupation army of the 1920s encouraged the German high command to approve colonial prisoner transfers to occupied France.35 Some Wehrmacht troops even claimed that killing West African tirailleur prisoners in June 1940 was revenge for the Rhine ‘‘horror.’’ Mossi troops from Côte d’Ivoire also appear to have suffered disproportionately as they could be singled out owing to their distinct facial scarification.36 There is also limited evidence of involuntary medical research conducted on Senegalese prisoners by German doctors investigating supposedly distinctive traits of African physiology. The wholesale transfer of black prisoners from Germany probably saved them from the most criminal excesses of Nazi racialism.37 Another incidental outcome of the Nazi aversion to colonial prisoner retention in Germany was that most ex-POWs still resident in France in 1943–44 escaped compulsory labor service outside occupied France. By contrast, released white colonial settlers still in the metropole became liable to the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO).38 The principal camps housing colonial POWs after their return to France, according to French Red Cross statistics, are given in table 1. Colonial POWs were also held at five camps in Holland (Borselle, Scheerenhoek, Koudekerke, Flessingue, and Amersfoort).39 Few systematic atrocities occurred in the Frontstalags, but isolated reports suggest random brutality. One such report detailed the killing of an unnamed Senegalese rifleman. A Frontstalag guard in Poitiers, dubbed ‘‘Capitaine Achtung’’ by the inmates, shot the prisoner for peeling potatoes clumsily. For the most part, however, the principal cruelty was the physical hardship of camp life without adequate food, heating, or winter clothing. Chronic foot infections, parasite infestations, and malnutrition were rife. More serious illnesses, such as typhus and tuberculosis, became increasingly prevalent.40 35 Keith L. Nelson, ‘‘The ‘Black Horror on the Rhine’: Race As a Factor in Post–World War I Diplomacy,’’ Journal of Modern History 42 (1970): 606–27; Moshe Gershovich, French Military Rule in Morocco: Colonialism and Its Consequences (London, 2000), 177–81. 36 Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts, 94–96; Lawler, Soldiers of Misfortune, 99–101. 37 MacKenzie, ‘‘The Treatment of Prisoners of War,’’ 504. 38 AN, F 92966, no. 1219/CAB/CO/ PG, Contrôleur d’Armée Bigard to Président, Comité Algérien d’Assistance aux Prisonniers de Guerre, 6 June 1944. 39 Camp information from AN, F92964, Sous-dossier: Croix Rouge; SHAT, 2P78/ D1, ‘‘Synthèse des résumés des rapports d’inspection de camps de prisonniers de guerre.’’ 40 SHA, 2P70/ D2, no. 21901, ‘‘Compte-rendu de captivité établi par un prisonnier indigène récemment libéré,’’ 7 July 1942. Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 96 of 143 French Historical Studies 668 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES Table 1 Principal camps housing colonial POWs after their return to France Frontstalag ( Joigny) Frontstalag (Rennes) Frontstalag (Chartres) Frontstalag (Toul) Frontstalag (Charleville, Ardennes) Frontstalag (Onesse-Laharie, Landes) Frontstalag (Saint-Médard, Gironde) Frontstalag (Savenay) Frontstalag (Haute-Saône) Frontstalag (Nancy) Frontstalag (Saumur) Frontstalag (Châlons-sur-Marne) Frontstalag (Amiens) Frontstalag (Bayonne) Source: Archives Nationales, F 9 2964, Sous-dossier: Croix Rouge; SHAT, 2P78/ D1, ‘‘Synthèse des résumés des rapports d’inspection de camps de prisonniers de guerre.’’ Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 By September 1940 the primary objective of Vichy’s military bureaucracy was to relocate colonial POWs to detention camps in a warmer climate rather than to secure their outright release or worry about their political indoctrination. However, the prisoner-of-war sections in the secretariats of war and of colonies were aware of the potential for dissent when colonial POWs were eventually released. The demobilization of indigène units during the late summer of 1940 revealed widespread antagonism to colonial authority. The Algerian situation caused greatest alarm. On 12 August 1940 the divisional head of the Algiers police spéciale warned that demobilized colonial troops threatened public order. Most returnees had gone through the thick of battle in May and June, and interrogation reports suggested that some former soldiers felt they had been used as mere cannon fodder. Administrative neglect and the lack of job opportunities were more common complaints after repatriation. French settler troops received the best of the agricultural land set aside for veterans, and other employment schemes, such as the development of the coastal fishing fleet between Bougie and Philippeville, went nowhere. On 2 September 1940, Colonel de Coislard de Monsabert, then director of Algeria’s office de démobilisation, criticized the government’s failure to provide back pay and reasonable job prospects to returning ex-servicemen. Veterans’ goodwill was essential to colonial control: ‘‘Les anciens militaires indigènes ont toujours été dans le bled, nos meilleurs agents de propagande loyaliste, le meilleur appui de l’influence et de l’autorité française.’’ 41 The plans for release and repatriation of colonial prisoners drawn up over the next two years rested on three pillars: (1) All returning POWs were to be interrogated, either in France or on disembarkation 41 SHA, Papiers Monsabert, 1K380/C4, Rapport de l’Office de Démobilisation, Alger, 2 Sept. 1940. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 97 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 669 in their home territory; (2) former prisoners would be demobilized only after satisfying their interviewers of their loyalty; and (3) military intelligence staff would monitor ex-prisoners’ movements until they returned to their families. On 18 December 1941 Darlan relayed these instructions to General Alphonse Juin, commander of the French armistice army in North Africa. All returning Maghrebi POWs were to be carefully screened. Three months later Juin confirmed that ‘‘une surveillance systèmatique’’ was in place throughout Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Few of the former POWs under police and army surveillance were considered actively pro-Axis, but Juin acknowledged that most of them nursed strong grievances about their time in captivity. Many of those interrogated blamed Vichy’s feebleness for food and clothing theft and for the lack of redress against the casual brutality of camp overseers. The French army had neither protected its colonial troops on the battlefield nor stood up for their interests as POWs.42 Doubting the loyalty of its Algerian and Tunisian troops, Vichy reverted to the rigidities of colonial control. These veterans would not be recompensed for their sacrifice but instead would be silenced and dispersed immediately after repatriation. Two other factors determined Vichy preoccupation with the reintegration of former colonial POWs. The first was the development of a multiplicity of government agencies and voluntary organizations to supervise French POW families and prisoner returnees. As much about social control as welfare provision, the centerpiece of this bureaucracy was the Commissariat Général au Reclassement des Prisonniers de Guerre, established in October 1941.43 The second was the evolution of German strategic thinking. Hitler’s readiness to strengthen the Vichy empire against British attack was offset by his reluctance to antagonize the Italian and Spanish governments, both of which hoped to seize African spoils from France. Intermittent Nazi willingness to reintegrate small numbers of POWs into Vichy’s colonial forces reflected this wider balancing act.44 Extraneous problems soon intervened. After the failure of the Anglo-Gaullist attack on Dakar in late September, Britain’s naval blockade of the loyalist empire and the southern zone tightened. Attempts to ship colonial prisoners to sub-Saharan Africa in particular were liable to end in capture. The Anglo-American invasion of 42 SHA, Archives de Moscou, C24/ D1749, EMA/SAM, Darlan to Juin, 18 Dec. 1941; Bureau des Menées Antinationales, Alger, no. 36, Juin to Darlan, 27 Mar. 1942. 43 Fishman, We Will Wait, 84–86; Lagrou, The Legacy of Nazi Occupation, 107–8. 44 Robert O. Paxton, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 (London, 1972), 73–76, 84, 86; Charles-Robert Ageron, ‘‘Les populations du Maghreb face à la propagande allemande,’’ Revue d’histoire de la deuxième guerre mondiale 114 (1979): 6–13. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 98 of 143 French Historical Studies 670 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES French North Africa and the scuttling of the Toulon fleet in November 1942 quashed any remaining hope that Vichy would repatriate colonial ex-POWs. Nazi Propaganda The concentration of colonial prisoners in occupied France was no obstacle to Nazi efforts to indoctrinate them. Abwehr intelligence service activity in the Frontstalags and Nazi propaganda specifically targeted at French colonial POWs focused almost exclusively on North African troops and on Algerians and Tunisians especially. In December 1940 the occupation administration established a Maghreb propaganda bureau. It included three separate country sections staffed by nationalist activists of the Parti Populaire Algérien and the Tunisian Néo-Destour. A handful of Maghrebi prisoners and former deserters were recruited as agents of this propaganda bureau to help inculcate pro-Germanism in French North Africa.45 With German assistance, the bureau made regular Arabic radio broadcasts to North African POWs. These typically included information on the whereabouts of fellow prisoners, readings from the Koran, and pro-Nazi ‘‘information bulletins.’’ Arabic newspapers were also distributed to Frontstalags. Three of these stood out. El djanir, an Arab review published in Berlin, charted Axis victories in North Africa and the Middle East. In addition, Maghrebi prisoners were allowed to produce their own propagandist newspapers. Lissane al-assir [The prisoners’ voice] and Al hilâl [The crescent] were specifically aimed at the North African prisoner population.46 Former soldiers acting as Axis propagandists were the result of initiatives carried out in individual Frontstalags. Camp commanders in occupied France made much of German respect for Islam, and some reminded Muslim POWs of supposed links between French weakness and the moral corruption that attended secularization. In camps housing a mixed colonial population, informants were allegedly recruited by preference from among the Algerians and Tunisians present.47 Moroccans were generally excluded. Among Algerian POWs, members of the 45 Ageron, ‘‘Les populations du Maghreb,’’ 19–20; Levisse-Touzé, L’Afrique du nord, 102– 9. Regarding French countermeasures in Algeria, see Mahfoud Kaddache, ‘‘L’opinion politique musulmane en Algérie et l’administration française (1939–1942),’’ Revue d’histoire de la deuxième guerre mondiale 114 (1979): 95–115. 46 AN, Secrétariat général du gouvernement, série F 60837, Service des affaires musulmanes, bulletin de renseignements, 20 Jan. 1945. 47 SHA, 2P70/ D2, no. 21901, ‘‘Compte-rendu de captivité établi par un prisonnier indigène récemment libéré,’’ 7 July 1942; Levisse-Touzé, L’Afrique du nord, 109–10. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 99 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 671 immigrant community in France and évolués from the predominantly Berber Kabylie were reportedly considered most receptive to an antiFrench message. Most Tunisian POWs were conscripts. They were less infused with French military tradition than Moroccan prisoners, the bulk of whom were long-service professionals strongly attached to the Armée d’Afrique. A January 1942 prisoner debrief report regarding Frontstalag 181 at Saumur is revealing. It indicates that only the Moroccan contingent of prisoners consistently rebuffed German approaches, even threatening ‘‘to cut off the heads’’ of any propagandists that dared approach them.48 Some of the most enthusiastic collaborators were transferred to the Luckenwald Stalag 3, fifty kilometers south of Berlin. Luckenwald was the main training center for Arab propagandists. The Abwehr also operated smaller training outposts near Dijon and Orléans. Selected North African junior officers, mainly educated évolués from the intellectual centers of Algiers, Tunis, and Fez, were coached in covert intelligence work techniques by plainclothes Abwehr agents. By March 1941 General Maxime Weygand’s military staff in Algiers estimated that some three thousand prisoners and political activists from French and British Arab territories had passed through the camp. Inmates were said to be ‘‘fort bien traitées (couscous, méchouis, fêtes indigènes, etc. . . .).’’ Some trainees returned to Frontstalags equipped with films, Arabic pamphlets, and articles for inclusion in the newspapers produced for Maghrebi POWs. Others either were sent to North Africa directly or were released in France where they posed as escapees to ease their passage through Vichy interrogation centers. Weygand’s command planned to fight this sedition in like fashion. Reliable Arab intermediaries were recruited in Algeria to denounce the Axis to fellow Arabs in those urban spaces that the colonial authorities found hardest to penetrate. These included native cafés, bathhouses, casbahs, and mosques.49 German intelligence agencies concealed their overall coordination of prisoner propaganda, taking pains to ensure that the views disseminated appeared spontaneous and authentically Arab in origin. The key responsibility here fell to camp commanders and Abwehr recruiters. They targeted literate, politically engaged prisoners, knowing that they were likely to be more sympathetic to alleged Nazi support for Islam and Arab national aspirations. British and French imperial policy in 48 SHA, Archives de Moscou, C24/ D1749, Renseignement no. 567, 27 Jan. 1942. 49 SHA, série 1P-Vichy, 1P89, no. 1175/ EMA-2, Weygand to Pétain, ‘‘Propagande allemande en Afrique du nord,’’ annex 3: Evadés Nord-Africains, 3 Mar. 1941. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 100 of 143 French Historical Studies 672 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES the late 1930s was a fertile propaganda source. British suppression of the Palestine Revolt of 1936–39 and its quasi-colonial exploitation of Egypt were matched by France’s refusal to implement promised independence treaties with Syria and Lebanon and the abrupt reversal of the Popular Front reform program in North Africa. Activists of the Parti Populaire Algérien and the Néo-Destour were sure to find some support among Maghrebi POWs. As in Palestine and Egypt, in French North Africa the growth of nationalist sentiment was triggered by internal social change. On the one hand, during the late 1930s the educated urban bourgeoisie increasingly saw the reassertion of their Arab and Muslim identity as an act of political defiance. On the other hand, the preferential allocation of land to French settlers and the increasing burden of state taxation drove peasant smallholders into worsening poverty. Both of these social groups were well represented among the Maghrebi POW population.50 The Frontstalag authorities exploited the sense of abandonment commonly felt among Maghrebi POWs. Algerian and Tunisian POWs in particular were encouraged to vent their grievances. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the Saint-Médard Frontstalag in the Gironde, the production center of the newspaper Prisoner’s Voice. The paper lambasted France for its disregard of Islamic culture, its exploitation of colonial peoples, and its decadence in the face of German strength. The paper’s editor, Si Ahmed, advised his fellow POWs to remain ‘‘good Muslims’’ and to ‘‘expect nothing’’ from Vichy. SDPG inspection staff also fueled POW anger. At the Clisson Frontstalag in the Vendée inspectors asked to see white and colonial prisoners separately. The camp commandant denied the request, loudly insisting that North African POWs were entitled to the same treatment as whites. By contrast, no objections were raised to the cursory inspection of black African prisoners.51 The Nazi use of selected North African POWs as camp guards and informants increased as the manpower demands of the eastern front expanded after June 1941. POW interrogation reports suggest that in isolated cases this process went very far indeed. At Saumur where hostility between Maghrebi POWs was particularly severe, North African 50 David Yisraeli, ‘‘The Third Reich and Palestine,’’ Middle Eastern Studies 7 (1971): 343–54; Israel Gershoni and James P. Jankowski, Redefining the Egyptian Nation, 1930–1945 (Cambridge, 1995), 255–56; Jacques Berque, French North Africa: The Maghrib between the Two World Wars (London, 1967), 265–75. 51 SHA, Archives de Moscou, C24/ D1749, Préfecture des Bouches-du-Rhône, Service des Affaires Algériennes, ‘‘Action anti-française d’un prisonnier indigène,’’ 20 Sept. 1941; EMA-2, Section des Affaires Musulmanes, ‘‘La propagande allemande auprès des prisonniers indigènes nordafricains,’’ 19 Oct. 1941. Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 101 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 673 guards, principally from Tunisia and Oranie, in western Algeria, even wore swastika armbands and were armed with lead pipes with which to mete out punishment.52 Elsewhere loyalties were contested more subtly. Several former prisoners told their Vichy interrogators that Austrian camp guards led by example. They avoided brutality and relaxed camp regulations where possible, notably during the celebration of Muslim festivals. Former German POWs of the 1914–18 war who had been detained in North Africa were also sought after by Frontstalag commanders to act as guards.Typically reservists, these guards often spoke Arabic and were considered more sympathetic to North African prisoners.53 At Frontstalag 190 in Charleville a German officer who had been imprisoned in Tunisia during the First World War reportedly assured the camp’s Tunisian POWs of his admiration for Néo-Destour leader Habib Bourguiba. The camp commander at Quimper, Brittany, was another First World War veteran. He had learned Arabic in a POW camp in Algeria and employed it to lecture the Frontstalag inmates about German supremacy.54 It is hard to believe that such hectoring won many converts. Inevitably, however, the focus of Nazi propaganda on one group of colonial POWs and the instances of collaboration among a tiny minority of North African prisoners caused acute social and racial divisions among mixed POW populations. The use of North African auxiliaries in camp policing heightened both racial awareness and racist antagonism among the colonial prisoners. Certain of Headrick’s attitude formation determinants mesh together here—above all, prolonged inactivity and the replacement of military discipline with a system of racial discrimination.55 The bitterest disputes related to the favorable treatment accorded to pro-German prisoners rather than to the contents of the pro-Axis propaganda disseminated in camps. At the Luçon Frontstalag, for instance, two POWs, one Martinican, the other Tunisian, won their freedom by promising to spread pro-German propaganda locally and in Paris.Their fellow POWs were evidently more infuriated by the release of these prisoners than by the means used to secure it.56 Similar events occurred elsewhere. At Charleville two Algerian tirailleur sergeants were freed in return for col- Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 52 SHA, Archives de Moscou, C24/ D1749, Renseignement no. 567, 27 Jan. 1942. 53 SHA, Archives de Moscou, C24/ D1749, EMA-2, Section des Affaires Musulmanes, Centre Interrogatoire de la IVe Division Militaire (Marseille), Compte-Rendu Hebdomadaire, 31 Mar. 1942. 54 SHA, ibid., Section des Affaires Musulmanes, Note de Renseignements no. 35, 15 Dec. 1941. 55 See n. 19 above. 56 See n. 52 above. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 102 of 143 French Historical Studies 674 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES laborating with Abwehr agents. Other Algerian noncommissioned officers at the Epinal Frontstalag allegedly assisted camp staff in return for cherished privileges including extra food rations and temporary passes to visit the town. Rewards such as these were frequently offered to any Maghrebi POW who denounced potential escapees to the Kommandantur.57 In July 1942 a French-educated Senegalese évolué submitted an extensive report to the secretariat of war detailing his experience in Frontstalags at Poitiers and Saint-Médard. According to this former prisoner, black Africans, Malgaches, Vietnamese, and West Indians stuck together. The bonds between them were forged through the hardships of their first winter in captivity. This contrasted with the worsening mutual animosity between these colonial prisoners and their counterparts from Algeria and Tunisia.58 In the Poitiers Frontstalag the friction among the camp population was largely the result of thefts of food and winter clothing from parcels sent to prisoners by the Red Cross and POW charities in France. However, other relatively minor incidents were also interpreted in racial terms. Algerians and Tunisians were said to have secured the easiest jobs inside the camp, especially much-prized work in the kitchens, and the educated North African prisoners reportedly attacked the supine Francophilia of the black African évolué elite. These arguments suggest that colonial prisoners perceived one another within a racial framework that mirrored the framework imposed by the German authorities. The solidarity among those placed at the bottom of this hierarchy was apparently matched on occasion by the racism of those at the top. As mentioned previously, loyalty to France was also fitted into this racial framework. The chief camp auxiliary at Saint-Médard, Ben Aïd, mocked the efforts of black African évolués to adopt French language and customs. He insisted that this proved the inferiority of black African culture next to the assertiveness of Arab nationalism.59 These interracial tensions intensified in the twelve months from November 1941 to October 1942. In November the SDPG secured German assent to repatriate a large number of North Africans among the colonial POW population. This led to further allegations of discriminatory treatment from black African prisoners. Negotiations for the release of 10,000 colonial POWs in November 1941 posited the repatria57 See n. 53 above. 58 SHA, 2P70/ D2, no. 21901, ‘‘Compte-rendu de captivité établi par un prisonnier indigène récemment libéré,’’ 7 July 1942. 59 Ibid. Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 103 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 675 tion of 6,200 North Africans and 3,800 West Africans.60 Vichy’s initial concentration on the release of Maghrebi POWs reflected two shortterm concerns. The first was to reintegrate North African troops repatriated from Syria after the Anglo-Gaullist invasion of June–July 1941 into the Armée d’Afrique in the Maghreb. The second was to repatriate some 1,200 North African POWs who had previously worked in the Moroccan mining industry in order to increase ore production at the Bou-Arfa and Djerada mines.61 More significant here is the evidence that some colonial POWs discerned a basic truth: Vichy’s POW policy was predicated on racialist lines consistent with Nazi ideology. The Failure of Bureaucracy Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 Vichy’s multilayered POW bureaucracy produced numerous overlapping functions, jurisdictional rivalries, and administrative inefficiencies. Sarah Fishman’s examination of the agencies supporting French POW wives highlights this bureaucratic confusion. The problem grew worse as certain agencies moved closer to an openly collaborationist position.62 At Vichy several ministries, each with a distinct prisonerof-war section, shared responsibility for colonial POWs. The war ministry, foreign ministry, interior ministry, and ministry of colonies (all renamed ‘‘secretariats’’ under Vichy) created departmental services des prisonniers de guerre. The secretariat of war and the ex-servicemen’s secretariat were the only ministries whose jurisdiction ran to all colonial troops irrespective of their countries of origin. The gulf between Vichy’s self-perception as an effective state authority and its limited jurisdictional and diplomatic reach was abundantly clear in the POW data meticulously compiled by the Comité Central d’Assistance aux Prisonniers de Guerre (CCAPG). In July 1942, for example, the secretariat of war calculated a total of 109,720 colonial prisoners in German hands. This figure was broken down into national groupings as shown in table 2. Yet the CCAPG acknowledged that the totals given were wholly inaccurate. It concluded that fewer than fifty thousand colonial POWs remained in captivity. This huge discrepancy was explained away as a result of several factors. First, the war ministry’s filing system for colonial POWs was incomplete. The snapshot of secretariat of war statistics shown in table 2 illustrates this point. 60 SHA, 2P85/ D1, no. 15205, Darlan circular to colonial commands, 29 Nov. 1941. The figures for North African POWs broke down as follows: 2,700 Moroccans, 2,000 Algerians, and 1,500 Tunisians. 61 SHA, 2P85/ D1, no. 993, Platon to Darlan, 17 Oct. 1941; SHA, 1P133/ D2, no. 12597/ DDSA, AFN armistice delegation note, 6 Dec. 1941. 62 Fishman, We Will Wait, 87–98. Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 104 of 143 French Historical Studies 676 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES Table 2 Total number of secretariat of war files listing individual colonial POWs (excluding North Africans) by country of origin, compiled July 1942 African POWs Files held French Indochina POWs Files held Ivory Coast Senegal French Sudan Guinea , , , , Annam Cochin-China Tonkin ‘‘Indochines’’ * , , , , Dahomey French West Africa Madagascar TOTAL: DECEASED: ESCAPED: FREED: , , , , , — , ‘‘Others’’ * , Other colonial POWs Guadaloupe Martinique New Caledonia Syria, Djibouti, French Guiana, Réunion, French India , — Files held , , No files kept , — — — Source: AN, F 9 2964, no. 367/CAB/CO/ PG, Contrôleur Bigard to Platon, 11 July 1942. *Precise nationality unknown to the secretariat of war Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 As several of the indistinct national classifications in table 2 suggest, Vichy’s colonial POW statistics were hopelessly vague. This was most apparent in the figure of 18,625 West African tirailleurs whose place of birth was unknown. Discrepancies such as these were compounded by the fact that large numbers of colonial troops had been captured in 1940 without record of personal or unit identification details. Few filled out detailed cartes de captivité. Others were known to their commanding officers and camp authorities only by a colloquial name. As a result, the secretariat of war and the ICRC lacked the details of family origins needed to trace POWs.63 Theoretically, the secretariat of war’s sous-direction des prisonniers de guerre in Paris received weekly lists detailing any changes in circumstance, such as the movement of prisoners between camps, hospitalization, or loss of life. This information guided decisions on captivity payments and pensions to prisoners’ relatives, as well as notifications in case of death. In fact, war ministry staff struggled to keep track 63 SHA, 2P78, ‘‘Rapport du colonel Dantan-Merlin—inspection au frontstalag 194 Nancy, 16–20 Feb. 1943.’’ Myron Echenberg has estimated that between fifteen and sixteen thousand West African troops were taken prisoner in June 1940 (Colonial Conscripts, 88–89). Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 105 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 677 of colonial prisoners’ transfers from their initial transit camps in Germany to Frontstalags in occupied France during late 1940. Further confusion resulted from the large-scale use of colonial POWs in labor units (Arbeitskommando). As a result, numerous colonial prisoners were denied their service entitlements, and their families did not receive due pension benefits.64 In May 1941 the secretariat of war advised the Dakar government-general to screen repatriated ex-POWs more closely. Former tirailleurs were complaining of abandonment and nonpayment of entitlements. Veteran POWs realized that Vichy’s reintegration policy was intended to disperse them rather than to satisfy their legitimate demands. In a letter intercepted by the postal censorship bureau, an unnamed Senegalese ex-prisoner warned his comrades still in France not to trust the authorities: ‘‘Ne quittez pas la France avant que tout ne soit reglé. Ici, en arrivant à Dakar, on ne vous paie pas, on ne vous appareille pas, on ne vous décore pas, on vous renvoie dans vos villages sans aucun moyen de vivre.’’ 65 Maintaining POW Loyalty Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 Vichy concern for colonial POW welfare was racially conceived and practiced in accordance with the regime’s developing interest in imperial regeneration.66 Even in captivity colonial prisoners were considered future agents of Pétainist imperialism. However, secretariat of colonies personnel acknowledged that, once repatriated, former POWs might not fulfill their role as colonial typecasts of Vichy’s hommes nouveaux. The evidence from initial repatriations suggested that veterans were becoming a resentful and politically sophisticated vanguard of nationalist dissent.67 The military chain of command among captured military personnel continued to apply in POW camps, but the reality of defeat and prolonged captivity eroded the stricter discipline previously upheld in the field. Furthermore, the ‘‘Stalag-Oflag’’ system segregated unit commanders and even junior officers from their former troops. This struck at the paternalist and racially framed style of command upheld by colo64 For details of metropolitan soldiers’ entitlements, see Fishman, ‘‘Waiting for the Captive Sons of France,’’ 183 n. 4. 65 SHA, 2P85/ D1, no. 2600, Direction des Troupes Coloniales to Colonies note, 12 May 1941. 66 Regarding Vichy racial and corporatist policies in West Africa, see Pascal Blanchard, ‘‘Discours, politique et propagande: L’AOF et les Africains au temps de la révolution nationale (1940–1944),’’ in AOF: Réalités et héritages, Sociétés ouest-africaines et ordre colonial, 1895–1960, ed. C. Becker, S. Mbaye, and I. Thioub (Dakar, 1997), 1:315–37. 67 On the homme nouveau ideal and its colonial dimension, see L. Yagil, ‘‘L’homme nouveau’’ et la révolution nationale de Vichy (Paris, 1997), 51–54, 74–78. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 106 of 143 French Historical Studies 678 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES niale and Armée d’Afrique officers to forge tighter unit cohesion and unbending loyalty among colonial soldiers.68 The political challenge facing Vichy’s POW bureaucracy in general was to ensure that French POWs accepted the new regime. Its task with colonial POWs in particular was to prove that the empire remained intact. Where dealings with French metropolitan POWs stressed a decisive political break with the past, dealings with colonial POWs emphasized an unbreakable continuity. Denied the opportunity to shape colonial troops’ political outlook in the ordinary context of French military practice and garrison life, the Vichy authorities utilized Pétainist ceremony in an effort to convince colonial POWs that the French empire was still a potent force. At the behest of Minister of Colonies Charles Platon the food parcels delivered to colonial POWs in April 1942 contained a few extras in commemoration of the ‘‘empire fortnight’’ decreed by Pétain.69 This token gesture was revealing. Official eagerness to involve the POWs in this latest celebration of the vitality of Vichy imperialism only underlined the true emptiness of the concept. At the start of 1942 few colonial POWs had received any word of their families since their capture. In July 1942 Platon asked the occupation authorities to permit the delivery of radios to all Frontstalags housing colonial prisoners. These POWs could then listen to regular Vichy broadcasts and, it was hoped, receive at least one weekly message relayed from their territory of origin in their native language. Platon’s chef du cabinet considered broadcast information especially important for illiterate prisoners who were immune to Vichy’s written propaganda and, it was feared, depressed by their inability to send letters or read news of family members back home.70 The SDPG was also anxious to support religious observance among Muslim POWs. Interrogation staff from the army’s Muslim affairs section warned that ‘‘pseudo-imams’’ were common in Frontstalags. Their prayer sessions reminded Muslim prisoners that colonial domination precluded true Islamic observance because it denied the individual genuine moral autonomy.71 In response, the SDPG appointed a Senegalese imam, Alioune Mamadou Kane, to tour Frontstalags and cele68 Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts, 89; Joe Lunn, ‘‘ ‘Les Races Guerrières’: Racial Preconceptions in the French Military about French West African Soldiers during the First World War,’’ Journal of Contemporary History 34 (1999): 527–30. 69 AN, F 92964, Sous-dossier: Ministères/Colonies, no. 264, Administrateur Prevaudeau to Contrôleur Bigard, 1 Apr. 1942. 70 AN, F 92964, Sous-dossier: Ministères/Colonies, no. 976/CAB/ PG, Directeur du Cabinet Demougeot (Colonies) to Paris delegate, Service des Prisonniers de Guerre, 11 July 1942. 71 SHA, Archives de Moscou, C24/ D1749, EMA-2, Section des Affaires Musulmanes, ‘‘L’action allemande auprès des prisonniers musulmans nord-africains,’’ n.d., 1942. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 107 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 679 brate customary Muslim festivals with West African tirailleurs.72 North African POWs attracted much greater attention in this respect. The 6,200 Maghrebi POWs released in late 1941 were processed through reception centers at Limoges and Châteauroux. Military intelligence officers interrogated all returning North African troops at these locations, warning them to disregard fascist propaganda.73 These interrogations also presented an opportunity to test the loyalty and religious commitment of POW returnees. Throughout late 1942 the SDPG encouraged the French Red Cross in Bordeaux to distribute Korans and Muslim calendars to the Frontstalags in southwestern France still holding Maghrebi POWs. Literate prisoners were encouraged to ‘‘serve as marabouts,’’ reading passages of the Koran to the faithful.74 The staff of the Paris Mosque also became more heavily involved in the care of Muslim POWs during the course of 1941 after S. Khaddour Ben Ghabrit, a senior mosque official, was appointed vice president of the Comité de Patronage aux Prisonniers Nord-Africains.75 The Torch landings of November 1942 signaled Vichy’s loss of control in French Africa. It was clear that few colonial POWs would be released in the future. Arrangements to ensure the continued loyalty of these detainees thus assumed added importance. With the regime driven from the heartland of its empire, Vichy’s imperialist propaganda was unlikely to carry much sway. A few ceremonial gestures toward colonial POWs continued. In November 1943 special parcels were made up for Malgache POWs in celebration of the Madagascan festival of Fandroana. A traditionally prepared meal of mutton and couscous was served to North African POWs during the festival of Aïd el-Kébir in January 1944.76 Although they were symbolically important, these pathetic gestures were marginal to the grinding routine of POW life. Arrangements for the reintegration of released POWs into civilian life also revealed the gap between ambitious bureaucratic planning and limited practical result.77 As Sarah Fishman has emphasized, the gov72 Catherine Akpo, ‘‘L’armée d’AOF et la deuxième guerre mondiale: Esquisse d’une intégration africaine,’’ in Becker, AOF: Réalités et héritages, 1:175. 73 SHA, 2P78, no. 16032, ‘‘Note pour le Cabinet du Ministre,’’ 24 Dec. 1941. 74 AN, F 92351, Comité Algérien d’Assistance aux Prisonniers de Guerre, note to Bonnaud, SDPG, 15 Sept. 1942. 75 Ibid. 76 SHA, 3P53/ D1, Commissariat Régional Militaire (Montpellier), ‘‘Célébration de la fête malgache ‘le fandroana,’’’ 29 Nov. 1943; no. 188, Commissariat Régional Militaire (Toulouse), ‘‘Célébration de l’aïd el-kébir,’’ 5 Jan. 1944. Similar plans for Vietnamese POWs to celebrate the Tet festival in 1943 fell through. 77 SHA, 2P68/ D1, Cabinet du Ministre (Guerre), ‘‘Note au sujet de la création d’un commissariat général aux prisonniers de guerre,’’ 16 Apr. 1941. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 108 of 143 French Historical Studies 680 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES ernment began organizing facilities for metropolitan prisoners only in response to advice from those already repatriated. Jolted into action, the Vichy authorities first lobbied for the release of key administrators and then encouraged these bureaucrats to form the Commissariat Général au Reclassement des Prisonniers de Guerre in September 1941.78 This group worked to protect the livelihoods of French POWs. It pressed employers to keep prisoners’ jobs open and sponsored regulations to protect POW tradesmen against new competitors. Backed by a network of mutual aid committees set up in each French département in May 1942, it also assisted in providing welfare support to POW families.79 Colonial prisoners were not catered to in the same way. Colonial subjects had no such entitlement to employment protection, nor was there a colonial administrative network to parallel the activities of the Commissariat Général in metropolitan France. On 14 March 1942 Pierre Havard, chef du cabinet to Interior Minister Pierre Pucheu, advised French prefects that the Commissariat Général would process returning POWs from their initial arrival at designated reception centers (maisons de prisonnier) to their receipt of new identity papers and to their ultimate reemployment.80 Meanwhile the secretariat of war had organized accommodation facilities at Marseille and Fréjus for North African and other colonial POWs prior to repatriation. Only escapees, who were interviewed at greater length than other POWs at a separate reception center in Clermont-Ferrand, were demobilized in France rather than on arrival in their home territory.81 By contrast, those Maghrebi and colonial POW returnees that passed through Marseille and Fréjus remained subject to military discipline in order to facilitate their rapid dispersal upon arrival back in their home territories. During 1942 unofficial accommodation centers were also established near the main clusters of colonial POW Frontstalags in northern and southwestern France. These offered temporary shelter to newly released prisoners and were run by voluntary agencies distinct from the Commissariat Général. There were three such shelters in Paris. One was under Red Cross control. Another operated from the Paris Mosque and was reserved for North African ex-POWs. As with parcel and mail deliveries in the POW camps, Maghrebi prisoners were offered more comprehensive support than their black African, Vietnamese, and West Indian counterparts. Even so, in September 1944 the provisional gov78 Fishman, We Will Wait, 84–85. 79 Ibid., 85–86. 80 AN, F 92007, SDPG Cabinet, no. 56/CAB, Pierre Havard circular to prefects, 14 Mar. 1942. 81 SHA, 2P85/D1, no. 13836, ‘‘Note pour le Cabinet du Ministre,’’ 18 Oct. 1941. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 109 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 681 ernment acknowledged that it could not verify the numbers of ex-POWs among the estimated twelve thousand North Africans then resident in Paris.82 Health Issues On 9 September 1940 General Huntziger asked the German armistice commissioners to consider either repatriating captured colonial troops or transferring them as POWs from camps in Germany to the milder climate of occupied France. He warned that West African, Madagascan, and Vietnamese soldiers were especially prone to infection in a cold, damp climate. Five days later Huntziger’s delegation and the armistice commission’s POW section focused on the risk of major pulmonary illness outbreaks among colonial POWs once winter arrived.83 In peacetime Armée Coloniale doctors conducted regular health checks on colonial units stationed in the metropole.84 Since General Charles Mangin’s organization of a force noire before the First World War, the French army staff had concentrated colonial garrisons in the Midi, often close to their ports of arrival.85 As its name suggests, this hivernage system was less a matter of logistical convenience than of concern over troop infection rates in cold winter conditions. The assumption that tuberculosis was rife within the immigrant community was integral to the popular characterization of colonial workers in interwar France. Even director Jean Renoir’s celebration of Popular Frontism in his 1936 film La vie est à nous depicted Algerian workers in this way.86 Hospital admission statistics compiled in Paris and Lyons during 1924 and 1927 did reveal high incidences of tuberculosis among Algerian workers.87 However, ill health among Maghreb immi82 Most former colonial POWs were thought to be living in the fifteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth arrondissements. ‘‘Several hundred’’ North African escapees gathered in Chartres after the Liberation, and a ‘‘substantial colony’’ of Maghrebi agricultural workers were employed around Melun. AN, F 60837, Service des Affaires Musulmanes, bulletin de renseignements, 18 Sept. 1944. 83 AN, F 92001/ D2, no. 151/40, Commission Allemande d’Armistice (CAA) Etat-Major– Prisonniers de Guerre to French delegation, 11 Sept. 1940. Ironically, in French West Africa the wartime incidence of tuberculosis was thought to be highest in those ports with a large European population; see Jean-Claude Cuisinier-Raynal, ‘‘L’hôpital principal de Dakar à l’époque de l’AOF de 1895 à 1958,’’ in Becker, AOF: Réalités et héritages, 2:1191. 84 AN, F 92002, no. 3690/ PG, Sous-Commission des Prisonniers de Guerre, Huntziger note for CAA Wiesbaden, 9 Sept. 1940. 85 Marc Michel, ‘‘Colonisation et défense nationale: Le général Mangin et la force noire,’’ Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains 145 (1987): 27–44. 86 David H. Slavin, ‘‘French Colonial Film before and after Itto: From Berber Myth to Race War,’’ French Historical Studies 21 (1998): 152–53. 87 Kamel Bouguessa, Aux sources du nationalisme algérien: Les pionniers du populisme révolutionnaire en marche (Algiers, 2000), 127–28. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 110 of 143 French Historical Studies 682 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES grants in particular was popularly associated with moral degeneracy, criminality, and cultural primitivism rather than with the low pay and squalid housing from which most North African workers found it impossible to escape. Police authorities had justified tighter surveillance of colonial immigrants on health grounds. The Service des Affaires Indigènes Nord-Africains, founded by the Paris prefecture of police in 1932, was infamous for its political surveillance of emergent nationalist groups, but it also ensured basic health care provisions to colonial workers. Its work in both contexts was driven by the racialist assumption that rapacious, disease-ridden colonial immigrants threatened to contaminate the French race.88 These crude stereotypes were deeply entrenched in French society before 1940. Discrimination against colonial immigrant workers in the First World War exploded the myth of a ‘‘color-blind France’’ wedded to racial egalitarianism. Quite apart from the pejorative characteristics attributed to individual immigrant groups, the common denominator in this racial stereotyping was the belief that colonial immigrants threatened public hygiene and the sexual purity of French women.89 Increased colonial immigration in the late 1920s reinforced these fears. Even when the rate of colonial immigration slowed after 1931, opinion poll evidence suggested that immigrant communities were widely considered socially disruptive and readily identifiable with labor agitation, crime, and sedition.90 Ironically, the orientalist imagery with which French tourists, cinemagoers, and visitors to the 1931 Colonial Exhibition were bombarded nourished fears of racial contamination in metropolitan France.91 Such racism found freer expression under Vichy. Policies of racial 88 Colonial workers, typically employed in poorly paid and often unhygienic jobs, were inevitably susceptible to illness. See Stéphane Sirot, ‘‘Les conditions de travail et les grèves des ouvriers coloniaux à Paris des lendemains de la première guerre mondiale à la veille du Front Populaire,’’ Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer 83 (1996): 65–92; Ralph Schor, L’opinion française et les étrangers en France 1919–1939 (Paris, 1985), 165–68. 89 See Tyler Stovall’s key articles ‘‘Color-blind France?: Colonial Workers during the First World War,’’ Race and Class 35 (1993): 35–55; and ‘‘The Color Line behind the Lines: Racial Violence in France during the Great War,’’ American Historical Review 103 (1998): 742–47. 90 Paul Lawrence, ‘‘‘Un flot d’agitateurs politiques, de fauteurs de désordre et de criminels’: Adverse Perceptions of Immigrants in France between the Wars,’’ French History 14 (2000): 202– 6, 212–13; Michael B. Miller, Shanghai on the Metro: Spies, Intrigue, and the French between the Wars (Berkeley, Calif., 1994), 64–65, 150–52. 91 Herman Lebovics, True France: The Wars over Cultural Identity (Ithaca, N.Y., 1992), 53–83; Ann Laura Stoler, ‘‘Sexual Affronts and Racial Frontiers: European Identities and the Cultural Politics of Exclusion in Colonial Southeast Asia,’’ in Tensions of Empire: Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, ed. Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler (Berkeley, Calif., 1997), 198–215. See also Nicola Cooper’s discussion of administrators tempted to ‘‘go native’’ in Vietnam in France in Indochina: Colonial Encounters (Oxford, 2001), 150–63. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 111 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 683 exclusion expressed the regime’s emphasis on the moral and demographic regeneration of a traditionalist France. Nowhere was this more apparent than in official fears of pulmonary epidemics among colonial POWs. Vichy concern about the health of these prisoners was a mixture of acquired military experience and marginal interest in the ideological transformation of the POWs themselves. The segregation of colonial prisoners was an indicator of the officials’ concerns. The isolation of colonial prisoners within the Frontstalag system and within Vichy’s epidemiological hospitals was redolent of the encadrement system of 1916 to 1918 that kept colonial workers strictly regimented in France.92 Where ideology did impinge on Vichy’s colonial POW health care policy, it created a contradictory amalgam of the regime’s hierarchized view of colonial races and the longer tradition of paternalist colonialism among native affairs officers and military doctors. Repatriation of metropolitan prisoners was central to Vichy’s pronatalist ambition to replenish the French population. Government health care specialists advised French POWs on diet, hygiene, and exercise.93 Instructions given to metropolitan POWs stressed their roles as fathers and heads of households, an obvious complement to the reactionary paternalism characteristic of Vichy policy toward prisoners’ wives.94 There were no parallel governmental practices among colonial prisoners for whom the one overriding health issue was the limitation of major contagious disease outbreaks; nor does it appear that Vichy’s colonial administrations drew on the example of famille du prisonnier social work in metropolitan France to monitor the wives of colonial POWs while their husbands were in captivity. Within France itself, however, the underlying paternalism of the officials involved in French POW wives’ welfare was mirrored among health visitors in the Frontstalags that housed colonial prisoners. Just as the wives of French POWs bore the full impact of Vichy’s reactionary conservatism in matters of social policy, family, and gender, 95 so colonial prisoners were made to fit Vichy’s racialized conception of the proper relationship between the French and their subject peoples.96 North African POWs were considered more self-reliant than their black African, Madagascan, Vietnamese, and West Indian peers. In this racial order Maghrebi soldiers might aspire to become constructeurs d’empire, 92 Stovall, ‘‘Color-blind France?’’ 41–47. 93 AN, F 92828/ D2, Services médicaux sociaux memo., 20 Feb. 1941. 94 Fishman, We Will Wait, 77–81. 95 Ibid., 78–83. 96 This was much resented by the Ivoirien POWs studied by Nancy Lawler; see Soldiers of Misfortune, 106. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 112 of 143 French Historical Studies 684 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES but their black African counterparts could never be more than the empire’s défenseurs.97 POWs from colonial Africa, Indochina, and Madagascar were effectively treated as children in regard to both health care provision and their perceived inability to withstand prolonged captivity without psychological collapse. The infantilization of prisoners was consistent with the tenor of colonial propaganda that cast indigènes as ‘‘children of the Marshal,’’ culturally unsophisticated and politically immature. The army’s widespread use of visual imagery, and cartoons in particular, to transmit basic factual and training information to colonial troops also compounded the tendency to patronize them.98 However, health care officials did not treat black African prisoners as a homogenous group. Finer distinctions were applied to the black African POW population between the majority of colonial sujets and the few educated West African évolués with limited citizenship rights. Hospitalized évolués received preferential treatment, whether as a privilege of their citizenship status or in deference to their perceived intelligence. However, separate care facilities for black African junior officers were not provided. This conformed to Wehrmacht refusal to grant the few black junior officers the privileges of their rank. Black African lieutenants and captains were usually transferred with their men to Frontstalags instead of being kept alongside French officers in Oflags. Prominent évolué POWs included Senegal’s future president, Léopold Sédar Senghor. According to his biographer, Senghor’s eighteen-month incarceration alongside raw tirailleur recruits cemented his views on racism and negritude, which he expressed in some of his most outstanding poetic work.99 Senghor’s sense of brotherhood was not shared by all black African POWs. In June 1941 the differential treatment accorded to évolués and sujets was cited in a secretariat of war report as the principal cause of disturbances among tirailleurs in the tuberculosis wards of the Sainte-Marguerite hospital in Marseille.100 Vichy propaganda highlighting solidarity among French prisoners thrown together in adversity collapsed in the face of mounting evidence that old political antagonisms persisted.101 Similarly, the official image of loyal colonial servicemen retaining their faith in French imperial benevolence disintegrated 97 Blanchard and Boëtsch, ‘‘Races et propagande coloniale,’’ 534–42. 98 Ginio, ‘‘Marshal Pétain Spoke to Schoolchildren,’’ 299; Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts, 90. 99 Vaillant, Black, French, and African, 171, 175–76. 100 SHA, 2P85/ D1, no. 3321, note by Roger Blaizot, Directeur des Troupes Coloniales, 23 June 1941. 101 Fishman, ‘‘Grand Delusions,’’ 235, 241. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 113 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 685 as differential treatment compounded the manifest inadequacy of prisoner health care. Tuberculosis among Prisoners In its prewar advice on suitable locations for colonial garrisons in France, the medical service of the French colonial army had stressed that black African troops were unusually susceptible to tuberculosis infection and to secondary complications that could prove fatal. Commandant Bonnaud, a coloniale military doctor who now headed the SDPG camp inspection staff, was well acquainted with this. Prior to the war he worked at Fréjus hospital, which housed an isolation ward for tirailleurs infected with tuberculosis (TB). The autopsies Bonnaud conducted at the hospital indicated that secondary pneumonia was a major killer of African troops.102 Bonnaud and his fellow SDPG inspectors were most intimately involved in monitoring the health of the POW population.Their inspection reports provided Scapini with the raw data necessary to negotiate improvements in camp conditions and prisoner welfare.103 Bonnaud submitted a preliminary memorandum on the risk of TB infection among colonial POWs to the Paris region health service in November 1940. He stressed the importance of early diagnosis and his belief that TB infection was a certainty unless colonial prisoners were moved to camps in a mild, dry winter climate. Bonnaud’s characterization of the tirailleur patient combined the paternalist racial stereotyping typical of coloniale officers with a genuine concern for troop welfare. West African troops hospitalized with TB were, he said, like infants. Some could not comprehend the magnitude of their illness while others became easily depressed. Most refused to take restorative food and unfamiliar medicine. By November 1940 the SDPG had evidence of the first tuberculosis fatalities among colonial POWs. Contrary to expectations, this evidence indicated that North African troops were suffering as badly as black Africans. At Daumesne hospital in Fontainebleu, twenty-two Maghrebi POWs had died of TB since 20 September 1940, and 60 percent of the hospitalized colonial POWs from Frontstalags in the Orléans region were suffering from pulmonary illnesses. Bonnaud 102 AN, F 92351, SDPG, inspections de Frontstalags, Bonnaud memo, ‘‘Rapport au sujet des cas de tuberculose pulmonaire observés chez les militaires indigènes,’’ n.d., Nov. 1940. 103 Myron Echenberg made good use of the most detailed published account of the conditions of colonial POWs as revealed by camp inspections, Hélène de Gobineau’s Noblesse d’Afrique published in 1946; see Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts, 97. Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 114 of 143 French Historical Studies 686 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES reached a stark conclusion: unless relocation proceeded and a system of screening for the early signs of TB was put in place, ‘‘certains camps peuvent être litteralement décimés.’’ 104 SDPG lobbying for the transfer of colonial POWs to Frontstalags in southern France met with mixed success. On 15 January 1941, General Besson, director of the war ministry POW service, still awaited a reply from the German high command to Huntziger’s autumn 1940 requests for the movement of colonial troops.105 In subsequent weeks limited transfers did occur. Frontstalags 195, 221, and 222 in southwestern France (Onesse-Laharie, Saint-Médard, and Bayonne) all profited more from warmer winter temperatures than their equivalents in the Paris and Orléans region, especially those on the Marne and in the Ardennes. However, most colonial prisoners remained in Frontstalags across northern France. This was particularly the case for North African soldiers mistakenly deemed more resistant than black Africans to pulmonary illness. In reality, data compiled by medical officials in occupied France in August 1941 indicated that 188 of the 218 North African POWs known to have died in captivity were victims of tuberculosis.106 Bonnaud made limited progress in his plans to implement camp TB screenings. Health checks were patchy and too late to prevent the spread of TB infection among POWs over the winter of 1940–41. By April 1941 Bonnaud’s earlier prediction was proven correct. In the worst single outbreak, seventy-six colonial prisoners contracted TB at Frontstalag 230 in Poitiers. ‘‘Numerous cases’’ were reported from other northern camps at Saumur, Joigny, Nancy, Epinal, and Laon.107 In total, the SDPG registered 497 deaths among colonial POWs held in occupied France from July 1940 to 15 May 1941. However, this figure was not definitive. Scapini’s staff could not establish the overall number of colonial prisoners nor their distribution by nationality.108 Effective testing for tuberculosis required X rays of the chest cavity. These could indicate the presence of TB before the patient exhibited symptoms. After consultation with the Institut Prophylactique in Paris, Bonnaud put forward a simple plan in late May 1941. A mobile X-ray service staffed by French Red Cross personnel would visit Frontstalags one by one to examine all able-bodied colonial prisoners. Those found Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 104 See n. 102 above; Recham, Les musulmans algériens, 217–18. 105 AN, F 92828/ D3, no. 1082/CAB, Besson to directeur de l’établissement national d’Indret, 15 Jan. 1941. 106 SHA, 2P85/ D1, General Georges to secretariat of war service social, 28 Aug. 1941. 107 AN, F 92351, ‘‘Visite du docteur Bonnaud, le 21 avril 1941.’’ High rates of syphilis were also reported from several of these camps, the highest being thirty confirmed cases in Saumur. 108 AN, F 92351, SDPG, ‘‘Indigènes: Mortalité dans les camps de prisonniers de guerre de la France occupée, période du 15 mai au 15 octobre 1941.’’ Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 115 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 687 Table 3 French Red Cross X-ray inspections of Frontstalag prisoners, 1 January–10 February 1942 Whites Algerians Moroccans Tunisians Malgaches ‘‘Noirs’’ Antillais Prisoner inspections Confirmed TB cases Percentage infected Suspected cases Total cases Overall percentage infected . % . % .% .% . % .% .% .% .% .% .% . % . % . % Source: Archives Nationales, F 9 2351, Croix Rouge, ‘‘Résultats des examens de radiophotographie systématique pratiqués dans les Frontstalags,’’ 1 Jan.–10 Feb. 1942. Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 to be infected could then be placed in isolation at an earlier stage of the disease, diminishing infection rates in the camps’ cramped conditions.109 Bonnaud secured approval for this medical inspection system in October 1941. By the time the mobile screening service began its work in earnest, the spread of tuberculosis among colonial prisoners was much worse than it had been at the time of Bonnaud’s first report. In one of the first such visits in late October, some eight hundred West African, Maghrebi, and Madagascan POWs were X-rayed at the Epinal Frontstalag (121). These prisoners were by that time assigned to public works projects, principally in forestry and farming in the Vosges and Haute-Marne and returned to crowded dormitories after the day’s work. Three hundred and fifty were found to have traces of pulmonary illness. At least in this instance, authorities took swift action. This was thanks to the intervention of a M. Le Barillier, president of a local voluntary group, the Comité d’Aide aux Blessés Malades et Prisonniers de la Place Epinal. His group evacuated 250 of the worst affected Epinal POWs by train to hospitals in the southern zone. This combination of belated official intervention and de facto reliance on voluntary agency support was typical of Vichy’s POW provisions.110 The epidemic scale of TB infection among colonial POWs is shown in table 3, which records the results of Red Cross medical inspections for January and February 1942. As table 3 suggests, the Vichy authori109 AN, F 92351, Bonnaud letter to Dr. Vernes, Institut Prophylactique (Paris), 27 May 1941. 110 AN, F 92351, CSAL/ N, ‘‘Notes sur une mission de M. Brault dans la région de l’Est,’’ 18 Nov. 1941. Published by Duke University Press 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 116 of 143 French Historical Studies 688 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES ties and the Frontstalag medical services failed to rid camps of TB. The disease remained the primary cause of death among colonial POWs throughout the war. Ironically, the evidence of high infection rates among white prisoners only reinforced the view among Vichy health officials that colonial servicemen were potential disease carriers. According to official estimates, one-third of all West African tirailleurs released from Frontstalags before 1 October 1942 were seriously ill, most with either tuberculosis or dysentery.111 A note of warning here: doctors sometimes falsified diagnoses to their German overseers in order to ensure colonial prisoners’ transfers to better conditions.112 There is no reason to believe, however, that these false diagnoses were incorporated into the secretariat of war’s internal figures.The army staff needed accurate information about the numbers of POWs fit enough to resume active service and those requiring immediate repatriation after their release. Release and Repatriation Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 By 1944 Vichy’s failure to meet its initial promises of larger numbers of prisoner releases and improved camp conditions was sorely apparent to the metropolitan population. The Laval government’s introduction of the relève over the summer of 1942 transformed the stakes involved in POW affairs by trading specialist French workers for the German economy with prisoner returnees. On 4 September 1942 the scheme was made compulsory for adult males between eighteen and fifty and for unmarried women aged between twenty-one and thirty-five.113 As for colonial prisoners, the disproportionately high incidence of camp fatalities and the lamentable physical conditions of surviving prisoners confirmed the truth of Bonnaud’s 1940 prediction about the ravages of tuberculosis. During 1943 and 1944 the war ministry’s prisoners of war service faced mounting public criticism of its failure to safeguard colonial POWs. After the Torch landings, public awareness of the isolation and ill health of North African prisoners in particular increased.114 Colonial POWs were doubly disadvantaged. Their material conditions were not only tied to the course of Germany’s war in Europe but also to the outcome of Vichy’s colonial confrontations with the western allies.115 111 Akpo, ‘‘L’armée d’AOF,’’ 74. 112 Lawler, Soldiers of Misfortune, 112. 113 Roderick Kedward, In Search of the Maquis: Rural Resistance in Southern France, 1942–1944 (Oxford, 1993), 1–2. 114 ‘‘S’occupe-t-on des 50,000 captifs Africains?,’’ Le petit parisien, 10 Dec. 1942. 115 AN, F 92966, Secrétariat d’Etat aux Colonies, ‘‘Note a/s assistance coloniale aux prisonniers de guerre,’’ n.d., Aug. 1943. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 117 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 689 By late 1943 Colonial Minister Bléhaut’s cabinet staff were animated by the fear that a collapse of prisoner morale would be swiftly followed by the liberation of Frontstalags and the return home of a colonial POW population antagonistic to France.116 After the gradual collapse of Vichy state provision for colonial prisoners, the speed with which the provisional government authorities assembled former colonial POWs in transit centers in preparation for their repatriation in 1944–45 seemed to herald an improvement. Ex-POWs from the Maghreb whose age or terms of enlistment exempted them from transfer to General de Lattre’s ‘‘First Army’’ were generally shipped home via Marseille from September 1944 onward. Those returning directly from Frontstalags first had to pass through a camp de décantation where they were interviewed by Arab-speaking military intelligence officers.117 For the great majority that passed through this hurdle, welcoming committees awaited them at the ports of Casablanca, Algiers, Bizerta, and Tunis and at the major North African railway stations handling returning prisoners.118 In Tunisia, for example, the local ex-servicemen’s association, led by retired indigène officer Lieutenant Saffraouine, distributed shoes and both European and traditional Arab dress to all Tunisian ex-POWs. Tradesmen and industrial workers were issued legal documentation confirming their right to return to their former employment.119 Most important for the nervous Gaullist authorities, across French North Africa demobilization measures were carefully prepared to ensure that all former POWs were swiftly processed and dispersed back to their families, usually within three days of arrival.120 The scrupulous preparation for the repatriation, dispersal, and welfare of North African ex-POWs was not copied south of the Sahara. During late 1944 and 1945 West African troops faced severe privation and long delays before securing passage home, and the provisional government’s insensitive refusal either to acknowledge the key role of colonial forces in the Free French war effort or to meet legitimate troop grievances over pay and pensions provoked violent protests 116 AN, F 92966, no. 1544/CAB/ EG/ PG, Bigard note, ‘‘Réunion du 9 novembre 1943 au ministère des colonies,’’ 18 Nov. 1943. 117 SHA, 2H174/ D4, Commandement Supérieur des Troupes de Tunisie, Services des Affaires Musulmanes Compte-Rendu, 28 Sept. 1944. 118 The Moroccan Residency, for instance, advised local army commands that reception ceremonies were to be ‘‘aussi imposante que possible.’’ SHA, 2H174/ D4, Commandement Supérieur des Troupes de Maroc, note de service, 28 Sept. 1944. 119 SHA, 2H174/D4, no. 881 EMGG-1, ‘‘Instruction relative à l’utilisation des indigènes nord-africains prisonniers et déportés récupérés en métropole,’’ 27 Oct. 1944; no. 440/S, Tunisian government secretariat to Resident-General Mast, 9 Dec. 1944. Returning Tunisian soldiers classified as peasant farmers did not receive any legal assurances regarding their jobs or land. 120 SHA, 2H174/ D4, no. 1193/ EMA-LIB, war minister to CSTT, 28 May 1945. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 118 of 143 French Historical Studies 690 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES among black African troops. As is well known, these tensions climaxed in the killing of at least thirty-five former tirailleurs during rioting at the Thiaroye barracks outside Dakar on 1 December 1944. The provisional government bore the brunt of ex-POW anger, but Echenberg is surely right in his conclusion that the violence of 1944 was the product of tensions built up during the preceding years of captivity. As he puts it, neither Vichy nor the provisional government recognized ‘‘the degree to which the African ex-POWs had acquired a heightened consciousness of themselves as Africans united by their shared experience in suffering.’’ 121 Former prisoners of war need to be factored into the political mobilization of African veterans after 1945. The clutch of influential exservicemen’s associations that emerged throughout the postwar empire offers a promising avenue for further research. Given existing records, the difficulty lies in separating out former POWs from other colonial veterans. Former Senegalese POWs were instrumental in the establishment of the short-lived Mouvement Nationaliste Africain in French West Africa, but elsewhere the influence of ex-POWs on other veterans is harder to discern. The following examples illustrate this point. In July 1945 Cameroon troops still serving in the French army founded a national section of the Front Intercolonial (FI), a Paris-based panAfricanist organization. In Cameroon the movement was dominated by ex-servicemen incensed by the settler community’s grip on power. Returning ex-servicemen also figured alongside civil servants and urban traders as distinct organizational groups in the first political parties to emerge in Guinea after 1945.122 In neither case were POWs major players among ex-servicemen’s associations. For several leading activists of the Parti Populaire Algérien, including three members of the party’s central committee, wartime military service marked their first experience of life outside Algeria. Ironically, while none were POWs, senior Parti Populaire Algérien leaders spent much of the war interned or under house arrest.123 121 See Echenberg, Colonial Conscripts, 97–104 (quote at 103), and his ‘‘Tragedy at Thiaroye: The Senegalese Soldiers’ Uprising of 1944,’’ in African Labor History, ed. R. Cohen, J. Copans, and P. Gutland (Los Angeles, 1978), 109–28. Thiaroye was the worst of a number of protests by exPOWs and demobilized African troops held in transit camps during late 1944. 122 Richard Joseph, ‘‘Radical Nationalism in French Africa: The Case of Cameroon,’’ and Lansiné Kaba, ‘‘From Colonialism to Autocracy: Guinea under Sékou Touré, 1957–1984,’’ both in Gifford and Louis, Decolonization and African Independence, 230–31 and 322–24. 123 Benjamin Stora, ‘‘Continuité et ruptures dans la direction nationaliste algérienne à la veille du 1er novembre 1954,’’ in Les chemins de la décolonisation de l’empire français, 1936–1956, ed. Charles-Robert Ageron (Paris, 1986), 406–7. Published by Duke University Press Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 119 of 143 French Historical Studies FRENCH COLONIAL PRISONERS OF WAR, 1940–1944 691 Conclusion The fate of France’s colonial prisoners of war was proof of the weakness, the crass inefficiency, and the underlying hypocrisy of the Vichy state. Dependent peoples within a colonial system are typically denied the freedoms and basic rights of their metropolitan rulers. Superficially, the discriminatory treatment faced by colonial POWs merely confirmed this, much as the experience of colonial immigrant workers had done in the First World War. But colonial POWs were held captive by an avowedly racist state and relied for protection on a regime whose racialized conception of empire informed all aspects of POW policy. Their mistreatment did not reach the genocidal dimensions of German neglect of Soviet prisoners. The deaths of at least 3.3 million Soviet soldiers, 57 percent of all those captured, suggest that only when Nazi concepts of racial inferiority were reinforced by acute ideological hatred did mass killing result.124 However, racial considerations nonetheless determined the outlook of the colonial POWs’ captors and the outlook of their supposed Vichy protectors. Veteran colonial soldiers had been prized as intermediaries capable of generating loyalty to France within their own communities. That commitment demanded an obfuscation of their status as members of a subjugated, colonized population, something typically achieved by the award of citizen status and limited pension rights. Colonial prisoners did not take on this intermediary role. Their prolonged incarceration sapped their loyalty to army and nation. They were frequently denied even the most basic rewards for service hitherto granted to colonial conscripts, and Vichy’s feeble efforts to safeguard them—from initial capture through illness to eventual repatriation—laid bare the crude racialism that underpinned French colonialism and Vichy imperial policy. Colonial prisoners never ranked alongside their metropolitan counterparts as a distinct constituency with the potential to assist in the reconstruction of a new imperialist France. Even in the unique circumstances of wartime detention, the ethnic hierarchy of colonialism was reinforced. North Africans generally fared better than black Africans, and évolués could expect more attention than sujets. As numerous official agencies sprang up to serve the interests of the French prisoner population, very few appeared that were devoted to colonial POWs. Limited state provision must be related to a raft of colonial polices that intensified the exploitation of subject popu124 Omer Bartov, Hitler’s Army: Soldiers, Nazis, and War in the Third Reich (Oxford, 1991), 83; Theo J. Schulte, The German Army and Nazi Policies in Occupied Russia (Oxford, 1989), chap. 8; also cited in MacKenzie, ‘‘The Treatment of Prisoners of War,’’ 510. Published by Duke University Press 692 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES lations and legitimized differential treatment on racial grounds. Ultimately, Vichy attached greater importance to the lives of French prisoners than to those of its colonial troops. These troops’ diminishing chances of repatriation as the empire slipped from Vichy’s grasp made matters worse. Unlike Britain or the United States, Vichy could not compel the Nazi authorities to act with restraint by threatening acts of reprisal against a German prisoner population. The Vichy regime and the provisional government recognized that colonial prisoners might be important agents of postwar political change once returned to their home territories, but they did little to address this possibility. Instead, former POWs remained a powerful symbol of colonial inequity. Tseng 2002.8.22 07:36 6697 FRENCH HISTORICAL STUDIES 25:4 / sheet 120 of 143 French Historical Studies Published by Duke University Press