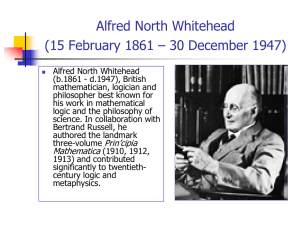

This article was downloaded by: [93.220.119.64] On: 04 August 2014, At: 09:29 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Parallax Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tpar20 Diffractive Propositions: Reading Alfred North Whitehead with Donna Haraway and Karen Barad Melanie Sehgal Published online: 11 Jul 2014. To cite this article: Melanie Sehgal (2014) Diffractive Propositions: Reading Alfred North Whitehead with Donna Haraway and Karen Barad, Parallax, 20:3, 188-201, DOI: 10.1080/13534645.2014.927625 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927625 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions parallax, 2014 Vol. 20, No. 3, 188–201, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927625 Diffractive Propositions: Reading Alfred North Whitehead with Donna Haraway and Karen Barad Melanie Sehgal (Received 17 July 2013; accepted 19 October 2013) Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 A stone drops into the water, disturbing its calm surface. The ripples caused by the splash form amplifying circles. A second stone drops. The new circles of water waves interfere with the first, thus forming a pattern. Diffraction denotes the phenomenon of interference generated by the encounter of waves, be it light, sound or water and, within quantum physics, of matter itself. Such a superposition of waves produces a diffraction or interference pattern that records, i.e. incorporates the trajectory of the waves.1 Donna Haraway draws on the optical phenomenon of diffraction as a metaphor and a method for knowledge production, because diffractions crucially differ from reflections. Whereas reflection is bound to ‘repeating the Sacred Image of the Same’, ‘diffraction patterns record the history of interaction, interference, reinforcement, difference’, as she points out.2 Haraway thus reclaims the imagery of optics, much criticized within feminist discourse. Rather than rejecting the non-innocent history of optical metaphors, this method is itself a diffractive one: in substituting diffraction for reflection it displaces the trajectory of Western epistemology and its potent optical imagery. This change of metaphors has far reaching implications for the way in which the practice of knowledge and theory production is conceptualized – precisely because diffraction is more than ‘merely a metaphor’. As a method, diffraction incorporates historicity and difference into the practice of theory itself. And in its emphasis on effects it is essentially pragmatic: it is a ‘technology for making consequential meanings’.3 However, as Haraway specifies, ‘a diffraction pattern does not map where differences appear, but rather maps where the effects of differences appear’.4 The pattern generated by two stones dropping into the water, for example, is both the effect and result of the event, the difference and the consequences it induces. Diffraction patterns are, in Karen Barad’s words, ‘patterns of difference that make a difference’.5 They are not classificatory, but rather performative. While Haraway focuses on the epistemological aspects of diffraction as a metaphor and method, Barad elaborates its ontological implications, drawing on quantum parallax 188 q 2014 Taylor & Francis Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 physics. As Barad never tires of emphasizing, it is a physical phenomenon that shatters accustomed assumptions about matter and meaning. As process and the result of a process at the same time, diffraction patterns render both how something became as well as what it is. Being is becoming. As a physical phenomenon, diffraction gained crucial importance in the still-ongoing discussions around the consequences and interpretations of quantum physics. But these consequences reach far beyond specialized discussions in theoretical physics. They touch on the core of how we think about the world on an everyday basis after Newtonian physics has lost its evidence. In Meeting the Universe Halfway Barad lucidly brings to the fore the way in which classical metaphysics has not only been thoroughly problematized within the humanities, but also has become untenable if the insights in the natural sciences of the twentieth century are followed through to their philosophical conclusions. Despite these problematizations of a classical metaphysics of individualism and presence, Barad argues, there is thus nevertheless a need to reconsider and reconstruct our metaphysical or ontological assumptions.6 Whereas classical metaphysics has implicitly relied on a particular physics, namely a Newtonian one, Barad tentatively suggests that, in the light of quantum theory diffraction phenomena, rather than denoting a specific type of phenomenon, appear to be ‘the fundamental constituents that make up the world’.7 However, to attribute an epistemological consideration of diffraction to Haraway and an ontological one to Barad seems a too hasty division of labour as the relation between epistemology and ontology is precisely what seems to be at stake in thinking about diffraction. The physics of diffraction not only forces us to reconsider what an entity ‘in its essence’ is, but brings the entire distribution of subject and object, knower and known, words and things, words and world under reconsideration. The relation between knower and known can no longer be described as one of distant gaze. To engage in a process of knowing is to be part of the equation, to be entangled in intraaction as Barad points out in her reading of twentieth century physicist Niels Bohr. Epistemology and ontology can no longer be kept apart. I would like to introduce the work of the mathematician and process philosopher Alfred North Whitehead (1861 –1947) into this discussion, because reading his work with Haraway’s and Barad’s – and vice versa – seems to me a way of precisely elucidating the relation between epistemology and ontology as it is put into question by the downfall of classical physics. As a contemporary to Einstein and Bohr, Whitehead was steeped in the debates within physics in the first half of the twentieth century and, just like Barad today, he was concerned with their philosophical as well as worldly consequences. Whitehead forcefully describes the impact of these revolutions: We supposed that nearly everything of importance about physics was known. Yes, there were a few obscure spots, strange anomalies having to do with the phenomena of radiation which physicists expected to be cleared up by 1900. They were. But in so being, the whole science blew up, and the Newtonian physics, which had been supposed to be fixed as the Everlasting Seat, were gone. Oh, they were and still are useful as a way of looking at things, but regarded as a final description of reality, no longer valid. Certitude was gone.8 parallax 189 His late work, from The Concept of Nature (1920) to Science and the Modern World (1925) and Process and Reality (1929) (and beyond), can be read as a grappling with these consequences, as an attempt to respond philosophically to the problem raised by the downfall of classical physics. What became evident in this discursive situation for Whitehead was that what had seemed to be accounting for reality as such – a Newtonian doctrine of matter – appeared to be an abstraction, accountable only for a certain realm of reality at a certain level of generalization. The point for Whitehead, however, was not to criticize Newtonian physics. Rather, the problem for him lay in the general philosophical and cultural interpretation of Newtonian or, as he further qualifies, ‘scientific materialism’. Whitehead discerns a central, albeit implicit, assumption in the modern view of nature as it derived from Newtonian physics: Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 that which expresses the most concrete aspect of nature is thought in terms of stuff, or matter, or material [ . . . ] which has the property of simple location in space and time. [ . . . ] [M]aterial can be said to be here in space and here in time [ . . . ] in a perfectly definite sense which does not require for its explanation any reference to other regions of space-time.9 Matter in modernity is considered as ‘simply located’, without relations, without a becoming – it is ‘merely’ matter, mechanically following the Newtonian laws. Whitehead questions this conception of matter not only because it runs counter to the findings of physics, from thermodynamics to the theory of relativity and quantum physics. He also problematizes it because of its inherent, unavowed metaphysics and anthropocentrism. Whitehead describes modern thinking as plagued by an incoherence that he locates in the very concept of nature itself. He describes this incoherence as ‘bifurcation of nature’ because, obviously ‘we’ humans exclude ourselves from the deterministic conception of nature it implies – we are not blindly determined, but are free, follow purposes and values. Again, Whitehead is concerned with the worldly consequences of what he considers a logical fallacy. Modern thought, in mistaking the Newtonian concept of matter, an abstraction, for something concrete, in consequence is trapped by the vice of ‘explaining away’: everything that does not fit into the ‘scientific materialist’ scheme is in consequence denied the status of existence proper; it is defaced as merely illusory, merely subjective, thus instantiating the rift between the realms of ‘nature’ and ‘culture’, subject and object, the human and non-human. This bifurcation in the concept of nature informed, and continues to inform, a whole culture of thought – the habits of thought constituting modernity. Such was the problem Whitehead understood to be posed by his epoch. As Isabelle Stengers has shown, his speculative philosophy can be read entirely as a response to this problem.10 His opus magnum, Process and Reality (1929), is an attempt to construct a metaphysics in which nature does not bifurcate – and thus to construct a frame of thought that avoids a ‘metaphysics of individualism’ (Barad), ‘human exceptionalism’ (Haraway) and a representationalist epistemology. It would be beyond the scope of this paper to develop precisely how Whitehead’s metaphysics answers to the challenge quantum physics posed to Western Sehgal 190 Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 metaphysical beliefs, and thus answers to what Barad calls for – an ontology that takes phenomena of diffraction ‘as the fundamental constituents that make up the world’.11 In the following, I would rather like to read Whitehead diffractively with Barad and Haraway in order to spell out a possible entanglement between ontology and epistemology beyond modern strictures and as pointed to in the discussion on diffraction. Such a reading is itself diffractive, because the point is not to show that Whitehead already knew what theorists two generations later would look for, but rather to read Whitehead today, in light of the shifts in twentieth century physics as well as postmodern concerns in the humanities.12 What does it mean to speak of ontology, cosmology and metaphysics today? How to reconcile the need of a new metaphysics with the recognition of our own semiotic technologies? Modern thought posits epistemology as ‘first philosophy’, such is the Copernican revolution that Kant effected precisely to restrain metaphysical speculation. In consequence, Whitehead’s metaphysics has been and continues to be widely read as a metaphysics in a classical, pre-Kantian sense. In contrast, I would like to suggest that reading Whitehead with Haraway and Barad shows that his reaffirmation of metaphysics is not to be construed as a return to pre-modern modes of thought which leave the subject out of the equation. Rather, such a reading radically changes the understanding of metaphysics – as of subjectivity – itself. Whitehead constructs a situated metaphysics in a double sense: his metaphysics answers to a problem posed by his own epoch – the bifurcation of nature – and it incorporates situatedness into its own theoretical practice.13 In other words, Whitehead undermines representationalism in his own conceptual practice. His situated metaphysics is a pragmatic one; it is committed to ‘making consequential meanings’. Whiteheadian concepts are speculative because they are pragmatic; they acquire meaning by the way they generate ‘consequential meanings’, not by a supposed capacity to mirror reality as such. A diffractive reading of Whitehead with Barad and Haraway not only accounts for the surprising convergence of these heterogeneous thinkers, it also accounts for the friction that such a bringing-together of heterogeneous texts necessarily generates, without explaining it away. This friction first and foremost manifests itself in the divergent styles of the two feminist philosophers and historians of science, writing at the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century, and the process philosopher, insisting on the necessity of coherence and systematicity within a new metaphysics, at the beginning of the twentieth century. For Haraway, situatedness and diffraction are writing technologies. Her histories of western science are necessarily and explicitly stories, populated by figures, indeed by a whole ‘theoretico-political zoo’, from the famous cyborg to her dog Cayenne to the genetically modified OncoMouse.14 These figures are markers of situatedness; they share the fate of inheriting ambivalent pasts (for instance, the imperialist space race of the Cold War era in the case of the cyborg). Rather than being a reason to give up on them, it is precisely these noninnocent pasts that call for a diffractive reading and rewriting for Haraway. Whitehead’s opus magnum, Process and Reality, seems far away from such a figurative and situated writing technology. Process and Reality is considered as extremely opaque parallax 191 in its excessive use of technical vocabulary. Not only do the ensuing difficulties for its readers seem to be in stark contrast with Whitehead’s own conception of philosophy as ‘sheer disclosure’,15 but Whitehead explicitly describes his speculative philosophy as an attempt to develop a systematic cosmology and a conceptual ‘scheme that should be coherent, logical, and in respect to its interpretation [of experience, MS], applicable and adequate’.16 Whitehead thus explicitly affirms modes of philosophic thinking that have been thoroughly problematized in the course of the twentieth century; his emphasis on metaphysics, speculation and cosmology seems to suggest a ‘view from nowhere’ and thus to run counter to all attempts to construct ‘situated knowledges’.17 Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 Nevertheless, in the following I would like to read Whitehead with Haraway and Barad and ask what incorporating situatedness into metaphysical thinking could precisely mean. What kind of conception of theory is necessary for and implied in such a renewal and reconsideration of metaphysics? I argue that by taking Whitehead’s particular conception of theory into account it becomes possible to make an interference pattern visible between Whitehead’s, Haraway’s and Barad’s thought. This interference pattern can also elucidate Whitehead’s insistence on coherence and systematicity, as well as his affirmation of metaphysics, which seem so hard to reconcile with post-modern concerns. By illuminating Whitehead’s specific notion of theory, I will argue, the speculative and situated conception of his metaphysics can come to the fore. This not only implies a metaphysical understanding of theory, but also opens up an understanding of his own metaphysics as a diffractive one. Whitehead uses the image of a stone splashing into calm waters precisely when developing his notion of theory. I have added a second stone to this metaphor, thus causing a diffraction pattern, which is precisely what I would like to do by reading Whitehead with Haraway and Barad and vice versa. Speculative starting points for quantum entanglements In the chapter on ‘Expression’ in Modes of Thought, Whitehead writes: ‘A thought is a tremendous mode of excitement. Like a stone thrown into a pond it disturbs the whole surface of our being’.18 Translated into the technical vocabulary of Process and Reality, this ‘splash’ refers to the functioning of propositions. Propositions – a much neglected category even among Whitehead scholars – could roughly be translated as ‘theory’; but it is important to note that propositions do not merely refer to explicit knowledge production, not even exclusively to the human activity of conscious thinking. Propositions are a metaphysical category – that is, they belong to the realm of existents.19 In the terminology of Process and Reality this means that they are required to describe actual entities – it is in respect to actual entities that propositions produce their disruptive ‘splash’. ‘Actual entity’ is a key concept in Whiteheadian metaphysics, standing at the core of his speculative project and its inherent critique of a – to use Baradian terms – ‘metaphysics of individualism’. Interestingly, Whitehead first introduces this concept in Science and the Modern World in a discussion of quantum phenomena Sehgal 192 and the paradox of the discontinuous orbit of electrons. Whitehead argues that there is only a paradox as long as we, explicitly or implicitly, assume Newtonian parameters of enduring matter through time and space. The difficulty vanishes however, ‘if we consent to apply to the apparently steady undifferentiated endurance of matter the same principles as those now accepted for sound and light’, that is, ‘vibration’.20 It is then that Whitehead for the first time introduces the concept of ‘actual entity’ that will reorient his whole thinking and engage him in the construction of a metaphysical system in which nature does not bifurcate. Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 But what are actual entities? ‘Actual entity’ is Whitehead’s term for all that exists in the full sense of what it means to exist. Actual entities designate the concrete: Actual entities [ . . . ] are the final real things of which the world is made up. There is no going behind actual entities to find anything more real. They differ among themselves [ . . . ] But, though there are gradations of importance, and diversities of function, yet in the principles which actuality exemplifies all are on the same level. The final facts are, all alike, actual entities.21 There are, of course, other kinds of entities, such as eternal objects and societies, or propositions. Indeed Whitehead, to use Haraway’s phrase, invents a whole ‘theoretical zoo’ of strange concepts and beings. But all these other kinds of entities essentially refer to actual entities as the locus of their concretion. They are the cornerstone of Whitehead’s empiricism.22 However, speaking of actual entities as ‘the final real things of which the world is made up’ could be misleading.23 They are decidedly not to be imagined as things – the concept is introduced precisely to circumvent the Newtonian focus on enduring entities, favouring a wave or vibratory model. Actual entities are constituted by mutual intra-actions that Whitehead calls ‘prehensions’. Each actual entity constitutes itself through a ‘cut’ (Barad), a ‘decision’ (Whitehead), incorporating and eliminating what matters into its very constitution.24 However, it is also not precise to describe actual entities as vibratory entities existing in a microscopic realm. This point might seem technical, but it is important because it touches firstly on the status of Whitehead’s concepts as speculative concepts, and secondly on their relation to specialized forms of knowledge, such as quantum physics for example. Whitehead’s point, I would like to argue, is not to develop a cosmology that is, finally, more true to the world, incorporating the most recent findings of physics. That would, on the one hand, imply accepting physics as foundational for all other modes of knowing and being in the world and thus run the risk of explaining other modes away. On the other hand, methodologically, it would imply sticking to a traditional understanding of metaphysics as mirroring the fundamental constituents of the world. Rather, Whitehead not only develops a different metaphysics but a different understanding of metaphysics – one in which epistemology and ontology, and even ethics, cannot be separated. Rather than procuring a new foundation, the task of metaphysics is to speculatively construct a hypothetical starting point for our heterogeneous fields of experience and knowledge, including everyday experience as well as the counter-intuitive findings of quantum physics, a starting point that parallax 193 will not lead to explaining away other forms of intra-action that make up and matter in the world’s becoming. Whitehead’s actual entities propose such a different starting point. Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 As stated at the outset, Whiteheadian concepts are speculative because they are pragmatic – their meaning depends wholly on the way they generate ‘consequential meanings’. The crucial difference the concept ‘actual entity’ dramatizes is the difference between existence as experienced and existence for its own sake. Specialized forms of experience never ‘prehend’ existence (the realm of actual entities) as such, they prehend it only according to specific and ‘interested’ modes of selection, emphasis and senses of importance. Thus, actual entities are not objects of (our) experience as such, not even methodologically guided experience in experimental apparatuses. What is experienced are – in the vocabulary of Process and Reality – societies, associations of actual entities forming a pattern, or in Barad’s terms ‘phenomena’: ‘intra-acting “agencies”’, ‘ontological entanglements’.25 Rather than being what we experience, actual entities are that from which we experience, what is presupposed by experience. And precisely because actual entities are never experienced as such – i.e. in a representationalist mode of a detached observer – the concept of actual entities is necessarily a speculative one. Therefore, even when Whitehead uses terms from psychology, like ‘prehension’ (dropping the various prefixes) or ‘feeling’ in order to describe actual entities, these concepts are decidedly not limited to human subjectivity. On the contrary, ‘feeling’, Whitehead insists, ‘is a mere technical term’.26 Every actual entity is a process of feeling; it is feeling the manifold data – and for Whitehead, in a Leibnizian vein, this data comprises all that there is, i.e. the world in its entirety – and turning it into the unity of its individual ‘satisfaction’. Countering modern habits of thought that let nature bifurcate, the ambition of the term ‘feeling’ is a monist one; to be a concept that can, in its generality, account for all kinds of existence.27 The use of terminology stemming from descriptions of human experience therefore does not imply any anthropocentrism on Whitehead’s part. To the contrary, this metaphysical and speculative generalization is his way of countering the ‘human exceptionalism’ in modern thinking that distinguishes between entities that feel, on the one hand, and entities that are ‘dead matter’, on the other. Thus, speculatively positing the realm of actual entities as a starting point for experience and thought importantly differs from the assumptions that mark modern thought; instead of a Cartesian dualism of mind and body and its inherent anthropocentrism, Whitehead proposes a monist and pluralist starting point, one which does not let nature bifurcate.28 It is a methodological and pragmatic postulate that not only proposes a radically non-modern beginning for quantum entanglements, but also implies a fundamental reconsideration of the relation between ontology (or metaphysics) and epistemology. Diffractive Propositions What are the consequences of such a speculative starting point for the conception of theory? How is this non-modern entanglement of epistemology and ontology spelt Sehgal 194 Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 out? As I suggested at the start, Whitehead, in response to modern incoherences and quantum challenges, proposes a metaphysical notion of theory. In order to understand what that could mean, it is necessary to delve deeper into the Whiteheadian universe, at the risk of becoming a little technical. But this is necessary in order to exhibit the experimentation in language that Whitehead’s metaphysics is – necessarily is as a way of diffracting modern habits of thought. Theories – or, in Whitehead’s technical term, ‘propositions’ – belong to the realm of existents; they matter. What are propositions and how precisely do they matter in the world? In its process of ‘concrescence’ – that is its process of becoming, of acquiring its definiteness, its singularity – an actual entity can dispose of, or ‘prehend’, four kinds of entities as its data: all other actual entities, eternal objects, societies and propositions. In order to understand the particularity of propositions, it is necessary to distinguish them from these other kinds of entities, and most importantly from eternal objects. While the prehension of all other actual entities assures the continuity of the universe, i.e. assures the conformation of each new actual entity with aspects of the ones it inherits, novelty in Whitehead’s metaphysics depends on what he terms ‘conceptual feeling’ – the prehension of eternal objects.29 Eternal objects designate the realm of pure potentiality; they are the ‘pure potentials for the specific determination of fact’.30 By means of selecting from these forms, the actual entity decides how it inherits its past. It is important that it is the actual entity that decides; the realm of potentiality in itself has no potential to act; eternal objects are neutral as to how they are prehended, they ‘tell no tales about their ingressions’ about how they might be entertained in experience.31 It is in this way that Whitehead secures his empiricism. When an actual entity ‘selects’ from these eternal forms, it is in fact prehending all of them, but it grades them in terms of relevance.32 Thus negative prehension – the discarding of possibility – is crucial; whatever exists is tinged by what might have been.33 Propositions – or as Whitehead defines them: ‘Matters of Fact in Potential Determination, or Impure Potentials for the Specific Determination of Matters of Fact, or Theories’ – stand between the entirely abstract nature of eternal objects and the realm of the concrete actual entities.34 In contrast to eternal objects that can be prehended by any actual entity, the reach of a proposition is already limited to specific actual entities. Whereas eternal objects are ‘entirely neutral, devoid of all suggestiveness’ as to how they will be incorporated in experience, having no efficacy of their own, propositions do exhibit such an efficacy; they are ‘a lure for feeling’.35 Despite his lifelong practice as a mathematician, Whitehead disagreed with the widespread view that propositions are mainly to be considered in view of their truth and falsehood and thus reducible to the function of being judged. It is here that thinking of propositions as theories in a customary, philosophical sense is particularly misleading. For Whitehead, the primary function of a proposition is not judgment, but entertainment. In a ‘world of pure experience’ – as Whitehead’s could be described in the words of William James – propositions, like all entities, need to manifest themselves in experience, the realm of actual entities. They need to be embodied. As with Haraway’s figures, a proposition ‘collects up the people; [it] parallax 195 Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 embodies shared meanings in stories that inhabit their audiences’.36 In Whitehead’s words: ‘A proposition is entertained when it is admitted into feeling. Horror, relief, purpose, are primarily feelings involving the entertainment of propositions’.37 This is why Whitehead emphasizes the fact that ‘in the real world it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is that it adds to interest’.38 Whitehead rebukes philosophers for their ‘favourite sin’:39 exaggeration, that is, extending what matters to them – logical propositions that take the form of judgments – to be propositions as such. Whitehead, on the contrary, emphasizes the importance of false and ‘non-conformal’ propositions (why else could a proposition that we know to be wrong utterly enrage and draw us into endless discussions and unexpected becomings?). But despite the strong ‘pull’ a proposition might exert, even it cannot determine, decide the way it is taken up; a proposition also ‘tells no tale about itself’.40 Even if propositions can indeed be true or false, their truthfulness is not immanent; it rather depends on the determinate actual entities from which it is an incomplete abstraction. Depending on actual entities to prehend it, a proposition ‘is a datum for feeling, awaiting a subject to feel it’.41 It is as such a datum that a proposition has ‘relevance to the actual world by means of its logical subjects that makes it a lure for feeling’.42 The efficacy of propositions, the way they matter, is thus a suggestive one: they elicit interest, divert attention and propose a way something is taken into account and what is likewise eliminated. In this way they account for difference, divergence and novelty in the various processes of intra-action. And different subjects (in the metaphysical sense of the actual entity) will feel a proposition differently, respond to it differently. It is thus the social environment, the historical and experiential world, that decides on the relevance of a proposition. In that sense, propositions have an empiricist bias; they have a particular relation to the world as it is. Always told after the fact, propositions take up the past of certain actual entities and divert their trajectory. As ‘the tales that perhaps might be told about particular actualities’ they are one possible way of making sense of a situation and at the same time they can lure it into a new becoming.43 Propositions are diffractive. In order to elucidate this diffractive character of propositions, specially nonconformal ones, it is important to remember the contention that propositions refer to actual entities rather than societies or phenomena as objects of experience. Again, Whitehead’s concepts are pragmatic concepts and thus can only be evaluated by their consequences. The difference between actual entities and societies lies first and foremost in their temporality. While actual entities are atomic – they become and perish – societies assure the continuity of the universe. The pragmatic consequence of this distinction is that, for Whitehead, continuity – the continuation of a society such as a body or social group – is considered an achievement. Continuity is not given; it is made, instance for instance. Intra-actions matter. With a slightly critical glance towards Bergson, Whitehead maintains that ‘[t]here is a becoming of continuity, but no continuity of becoming’.44 Since propositions refer to the atomic actual entities, when taken up, prehended, they introduce a break into the continuity of a becoming; they divert a historical route and lure it into a different becoming, they generate a different pattern. Thus ‘theory’ for Whitehead does not concern what factually exists. Theories disrupt the given, as a lure to what could be but not yet is. Sehgal 196 Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 This is why a ‘thought is a tremendous mode of excitement’ and ‘like a stone thrown into a pond [ . . . ] disturbs the whole surface of our being’.45 And yet, Whitehead later corrects – or rather diffracts – the metaphor of the stone splashing into calm waters. Keeping the distinction between actual entities and societies in mind, it is now possible to understand why: ‘But this image is inadequate. For we should conceive the ripples as effective in the creation of the plunge of the stone into the water. The ripples release the thought, and the thought augments and distorts the ripples’.46 That propositions operate on the level of actual entities implies that they operate on the pre-conscious, metaphysical level of feeling. In Barad’s words: ‘The world theorizes as well as experiments with itself’.47 Nevertheless, thinking about theories as a metaphysical entity in the Whiteheadian sense, thus pertaining to the world and not the human alone, has repercussions for how we think of theory and thought in a conventional sense. Propositions are neither to be equated with language nor thought; they are, rather, what is presupposed by language and conscious thinking. It is the excitement on the metaphysical level – the ripples – that then release, or better might release, a conscious, explicit thought in a ‘splash’! An explicit thought or phrase is the outcome of the tremendous excitement that propositions induce, if they successfully ‘lure a feeling’. Propositions thus point to the dimension of adventure in thinking, so crucial for Whitehead.48 They mark the speculative aspect of thought, that imaginative jump a phrase, a concept or a metaphor presupposes and produces, but never fully embodies in itself. Theories – in the Whiteheadian metaphysical sense of propositions – matter, they induce difference into the intra-active becoming of the world. They matter because they are diffractive. Whitehead’s Proposition or: a Metaphysics in the SF-mode In conclusion, I would like to develop what bearing this metaphysical and diffractive notion of theory has on Whitehead’s own ‘theory’, on his own practice and understanding of constructing a speculative metaphysics in the first place. What consequence does such a notion of theory have for the conception of metaphysics itself? Even if, for Whitehead as for Barad, with the downfall of classical metaphysics and the advent of quantum theory, it is not enough to critique classical metaphysics, but it becomes necessary to construct another metaphysics, it remains important to ask what it means to speak of metaphysics or ontology today. My contention is that the concept of metaphysics itself needs to radically change. Whitehead’s proposal for such a shift in the understanding of metaphysics becomes legible in a diffractive reading of his speculative philosophy through the work of Haraway and Barad; it is not merely a new ontology, but the entanglement of epistemology and ontology in an ‘ontoepistemology’–even an ‘ethico-onto-epistemology’ in view of constructing ‘situated knowledges’ – a situated metaphysics. In proposing an understanding of Whitehead’s metaphysics as a situated one, I would thus like to explore the possibilities such an understanding offers to negotiate the possible tension between the epistemological and ontological dimensions of diffraction. Reading Whitehead’s metaphysics as a situated one requires thinking his systematic efforts in tight connection to the works that have been read as purely historical.49 parallax 197 Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 In this perspective, Whitehead’s metaphysics, despite its abstract and technical language, can appear as less of an other-worldly and problematic endeavour than it might seem at first glance. Whitehead inherited a decidedly modern world, and it is in response to his reading of modernity that he is caught in the construction of a metaphysics at all. For Whitehead, constructing a speculative metaphysics or even a cosmology was nourished by a hope; the hope that the modern epoch with its fatal incoherences would come to an end. Hence Whitehead’s insistence on systematicity and coherence become readable as part of his critique of modern habits of thought. Whitehead’s metaphysics, I would argue, embodies an own proposition; What if, – this seems to be his question – we had a metaphysics, a frame of ideas, in which nature did not bifurcate? In which the fundamental constituents of the world are thought of not as self-identical essences but rather as phenomena of diffraction? To speak of hope here is not to add an emotional touch to hard systematic work. According to Whitehead, rationality is entirely misconstrued when understood as abstraction, deduction or induction. Rather, when he insists on the necessarily speculative dimension of rational thinking, Whitehead situates himself within a pragmatist lineage, pragmatism, for him, being the only philosophy providing a methodological response to the downfall of Newtonian physics – that is, to a discursive situation when ‘certitude was gone’. For pragmatism, thought is necessarily speculative. Because every process of knowledge production practically presupposes the faith in a possible solution, often against evidence, it necessitates its hypothetical formulation before evidence is found. In a leap of faith we ‘jump’ into a conclusion that can only be verified after the fact. Importantly, this precursive faith is necessary to bring about the conclusion.50 Knowing is part of the intra-action. For Whitehead, following James, theories therefore are not and never can be logically justifiable. Theories imply adventure, a risk that requires a leap of thought and imagination. Therefore, Whitehead’s hope vis-à-vis a perhaps no longer fully modern world is inherently linked to the way he conceives of the functioning of propositions. If Whitehead’s metaphysics embodies a proposition, its claim is not on metaphysics anew as first philosophy, nor is its aim to formulate a finally adequate conception about what is.51 Rather than being the place of timeless truths, Whitehead’s metaphysics is a situated one, itself lured by a proposition. It proposes one possible rendering of the world we inhabit, a possibly interesting and adequate one. But above all, its hope is the same as that of any proposition: to be relevant, that is, to be able to act as a ‘lure for feeling’ in a specific context. In the particular mode of philosophy – its specific social task being a ‘critic of abstractions’ – therefore Whitehead tries to lure his readers into other-than-modern modes of thought.52 Whitehead’s metaphysics is, in this sense, a diffractive one: it is ‘non-conformal’ (in Whitehead’s technical sense) to its social environment, an environment shaped by modern habits of thought, and it hopes to lure it into a different becoming. Whitehead thus – out of all things – suggests metaphysics as ‘another kind of critical consciousness at the end of this rather painful Christian millennium’ [my emphasis].53 Whitehead’s metaphysics can be read, again with Haraway, as a metaphysics ‘in the SF mode’, ‘committed to making a difference and not to repeating the Sacred Image of the Same’.54 A situated metaphysics embodies a diffractive proposition. Sehgal 198 Notes Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 1 For a detailed account of the physics of diffraction cf. Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007), p.80. 2 Donna Haraway, Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium.FemaleMan q_Meets_ OncoMouse TM (New York and London: Routledge, 1997), p.273. 3 Donna Haraway, Modest_Witness, p.273. 4 Donna Haraway, ‘The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/d Others’, in Cultural Studies, eds C. Nelson, L. Grossberg and PA Treichler (London: Routledge, 1992), pp.295– 337, p.300. 5 Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway, p.72. 6 Barad uses the term ontology rather than metaphysics. While the terms are neither identical nor separable within the history of philosophy, it is safe to say that both are equally problematic and need reworking. While Whitehead reconceptualizes the notion of metaphysics, Barad reformulates ontology as ‘onto-epistemology’ and further as ‘ethico-onto-epistemology’. Both agree in the fact that epistemology and ontology cannot be separated and are thus used alternately here. 7 Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway, p.72. 8 Lucien Price, Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead As Recorded by Lucien Price (Westport, CT: Greenword Press, 1977), p.4. 9 Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World (New York: The Free Press, 1967), p.49. 10 Isabelle Stengers, Thinking with Whitehead: A Free and Wild Creation of Concepts (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2011). 11 For an engagement with Whitehead and quantum physics, see for example Timothy E. Eastman and Hank Keeton, eds, Physics and Whitehead: Quantum, Process, and Experience (New York: State University of New York Press, 2004) as well as Isabelle Stengers, Thinking with Whitehead: A Free and Wild Creation of Concepts, trans. Michael Chase (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), pp.129–131, pp.166–170. 12 Such a diffractive reading of Whitehead, Haraway and Barad has its obvious and less obvious aspects. Haraway explicitly refers to Whitehead as part of her toolbox; there is thus a certain plausibility to anachronistically read Whitehead with Haraway. The obviousness of reading Barad and Whitehead together lies in the shared diagnosis of modern thought as well as the project that springs from it, of constructing a metaphysics or an ontology that rejects the implicit allegiance of modern philosophy with Newtonian physics. However, in Barad’s work Whitehead is entirely absent. 13 ‘Situatedness’ is here used in Haraway’s sense as developed in her seminal text ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, vol.14, no.3 (1988), pp.575– 599. I have developed the notion of a situated metaphysics in Whitehead in my ‘A Situated Metaphysics. Things, History and Pragmatic Speculation in A.N. Whitehead’, in The Allure of Things, eds. Roland Faber and Andrew Goffey (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). 14 Donna Haraway, The Haraway Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), p.300. 15 Alfred North Whitehead, Modes of Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1938), p.49. Stengers addresses this contrast in her ‘A Constructivist Approach to Whitehead’s Philosophical Adventure’ and throughout her major work Thinking with Whitehead. 16 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology (Corrected Edition), eds Donald W. Sherburne and David Ray Griffing (New York: The Free Press, 1985), p.3. 17 Reading Whitehead with Haraway and Barad as a situated metaphysics and inquiring into the entanglement of ontology and epistemology implies a comment on the recent discussions around the diverse renewals of speculative thinking. Unfortunately and significantly, what is lost in the debates around ‘speculative realism’ is precisely ‘situatedness’. The notions of metaphysics and speculation are not revisited, that is: what it means to construct a metaphysics in the twentieth century in the first place. Whereas ‘speculation’ for thinkers from Meillassoux to Harman refers, classically, to particular objects of thought as the absolute, speculation for Whitehead, in a pragmatist lineage, refers to the own practice of thought, emphasizing its situated character. This divergence in the ‘image of thought’ as one could say with Deleuze becomes manifest in the widespread misinterpretation of the concept of actual entity (see below and Melanie Sehgal, A Situated Metaphysics (2014)). 18 Alfred North Whitehead, Modes of Thought, p.50. 19 For Whitehead’s (short) list of categories of existence, see Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.22. 20 Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World, p.35. Following Barad’s reflection on quantum field theory even ‘vibration’ might suggest a too ‘steady’ form of being. Nevertheless, parallax 199 Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 I think that the concept of the actual entity precisely answers to the challenges posed by quantum field theory to classical ontology, e.g. in its assumptions concerning the conceptualization of particles and the void. For Whitehead as for Barad ‘even the smallest bits of matter are an unfathomable multitude. Each “individual” always already includes all possible intra-actions with “itself”. That is, every finite being is always already threaded through with an infinite alterity diffracted through being and time’, Karen Barad, ‘On Touching – The Inhuman that therefore I am’, Differences: A Journal of Feminist Studies, vol.23, no.3 (2012), p.214. 21 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.18. 22 Transforming traditional rationalisms as well as empiricisms, to search for a reason, for Whitehead, means to search for concrete elements in experience, not for some transcendent principle of reason: ‘Actual entities are the only reasons’, Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.24. 23 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.18. 24 Whitehead explicitly describes the actual entity’s ‘decision’ as ‘cutting off’: Giveness ‘refers to a “decision” whereby what is “given” is separated off from what for that occasion is “not given” [ . . . ]. The word “decision” does not here imply conscious judgement, though in some “decisions” consciousness will be a factor. The word is used in its root sense of a “cutting off”’, Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.43. 25 Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway, p.333. 26 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.164. 27 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.249. 28 Thus Whitehead’s actual entities can be read as an echo to Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘magic formula we all seek – MONISM ¼ PLURALISM’, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p.20. 29 Note that even conceptual feeling is nothing specifically human, every actual entity has a mental (as well a physical) pole. 30 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.32. 31 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.256. 32 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.69. 33 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.226. 34 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.22. Sehgal 200 35 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.33, p.259. 36 Vice versa, Haraway’s figures could be understood as incorporating a proposition. Historical figures as well as diagnosis of the present, they escape the judgment ‘true or false’, but are meant to be entertained. They are ‘lures for feeling’, embodying the hope of telling different stories of contemporary Technoscience. 37 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.188. 38 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.259. 39 Isabelle Stengers, Thinking with Whitehead, p.401. 40 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.257. 41 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.259. 42 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.259. 43 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.256 (my emphasis). 44 Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.35. 45 Alfred North Whitehead, Modes of Thought, p.36. The novelty propositions introduce is not necessarily good; no ‘theory’ is inherently good or bad – everything depends on the situation, the environment and the way a proposition is taken up, entertained, and its ‘ripples’ are prolonged or inhibited. 46 Alfred North Whitehead, Modes of Thought, p.36. 47 Karen Barad, ‘On Touching – The Inhuman that therefore I am’, p.207. 48 See Isabelle Stengers, ‘Achieving Coherence. The Importance of Whitehead’s 6th Category of Existence’, in Researching with Whitehead: System and Adventure, ed. Franz Riffert (Freiburg and Munich: Verlag Karl Alber, 2008), pp.59– 79, p.2. 49 That is Science and the Modern World [1925], Adventures of Ideas (New York: The Free Press, 1933) and Modes of Thought. 50 William James, ‘The Will to Believe’ in The Works of William James, eds Fredson Bowers, Frederick Burckhardt and Ignas K. Skrupskelis (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1979), vol.6. 51 Whitehead insists that ‘the explanatory purpose of philosophy is often misunderstood. Its business is to explain the emergence of the more abstract things from the more concrete things. It is a complete mistake to ask how concrete particular fact can be built up out of universals. The answer is, “In no way.” The true philosophic question is: How can concrete fact exhibit entities Downloaded by [93.220.119.64] at 09:29 04 August 2014 abstract from itself and yet participated in by its own nature? In other words, philosophy is explanatory of abstraction, and not of concreteness’ (Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality, p.20). 52 ‘You cannot think without abstractions; accordingly it is of the utmost importance to be vigilant in critically revising your modes of abstraction. It is here that philosophy finds its niche as essential to the healthy progress of society. It is the critic of abstractions. [ . . . ] An active school of philosophy is quite as important for the locomotion of ideas, as is an active school of railways engineers for the locomotion of fuel’ (Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World, p.59). 53 Donna Haraway, Modest_Witness, p.273. 54 Donna Haraway, Modest_Witness, p.273. Melanie Sehgal is Professor of Literature, Science and Media Studies at the European University Viadrina, Frankfurt/Oder. Her research spans from AngloAmerican philosophy and literature to Science and Technology Studies and new materialist feminist thought. She received her PhD in philosophy from the Technical University of Darmstadt with a dissertation on empiricism and speculative thinking in William James and Alfred North Whitehead. Recent publications include: ‘A Situated Metaphysics. Things, History and Pragmatic Speculation in A. N. Whitehead’, The Allure of Things, eds. Roland Faber and Andrew Goffey (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). Email: sehgal@europa-uni.de parallax 201