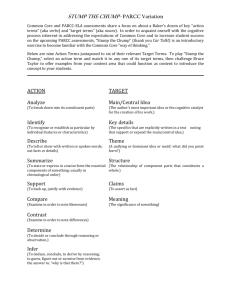

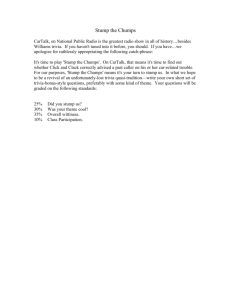

Original article doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00875.x Management of the rectal stump after emergency sub-total colectomy: which surgical option is associated with the lowest morbidity? J. P. Trickett, H. S. Tilney, A. M. Gudgeon, S. G. Mellor and D. P. Edwards Department of Colorectal Surgery, Frimley Park Hospital, Frimley, UK Received 19 April 2005; accepted 26 April 2005 Abstract Objective To identify the preferred surgical management of the rectal stump after emergency subtotal colectomy (ESC) for acute severe colitis by assessing the morbidity associated with each option. Patients and methods Consecutive patients undergoing ESC at a district general hospital between 1999 and 2004 were retrospectively audited for pathology, rectal stump complications and length of postoperative hospital stay (POS). Results Thirty-seven ESCs were performed, 34 were undertaken for disease refractory to medical treatment, 2 for toxic mega colon and 1 for perforation. Thirty-four cases were for ulcerative colitis, 2 Crohn’s colitis and 1 infective colitis. Twenty-seven had an intraperitoneal and 10 a subcutaneously placed closed rectal stump. The median POS for patients with a subcutaneously placed stump was shorter than for those with an intraperitoneal Introduction Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy with preservation of the rectal stump is established as the preferred operation for acute severe colitis which fails to respond to medical therapy [1–3]. The surgical management of the rectal stump, however, remains controversial. The options include creation of a low sigmoid mucous fistula, closure of the rectosigmoid but leaving the closed stump in the subcutaneous plane at the lower end of a midline wound, or closure of the rectal stump at the level of the sacral promontory (leaving the rectal suture ⁄ staple-line in the peritoneal cavity). The former options necessitate a Presented as a poster at the European Association of Coloproctology, Sitges, Spain. September 2003 Correspondence to: Mr D. P. Edwards, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Frimley Park Hospital, Frimley, GU16 7UJ, UK. E-mail: david.edwards@fph-tr.nhs.uk 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Colorectal Disease, 7, 519–522 stump, 8 and 15 days, respectively (P ¼ 0.04). Two patients had leakage from an intraperitoneal stump, prolonging POS (33 and 193 days). Three of the subcutaneous stumps leaked causing wound infection but not prolonging the POS (6, 7 and 16 days). Conclusion Avoiding a second stoma by closing the rectal stump after ESC has been confirmed as acceptable practice by studies over the last 15 years, reporting no overall increase in complications. The location of a closed rectal stump appears to influence the incidence of pelvic sepsis. The lowest pelvic sepsis rate is associated with subcutaneous placement; despite a higher wound infection rate this option appears to be associated with a lower total morbidity reflected in a shorter POS. Keywords Emergency sub-total colectomy (ESC), morbidity, rectal stump, surgical management longer stump and therefore greater risk of complications from the retained inflamed bowel; however, the latter option may result in an intraperitoneal leak from the closed rectal stump. Studies over the last 15 years have suggested that avoidance of a mucous fistula is not associated with an overall increase in the risk of pelvic sepsis (Table 1). In order to identify the preferred surgical option for a closed rectal stump, we reviewed the complications associated with our recent experience of the emergency subtotal colectomy (ESC). Patients and methods Consecutive patients undergoing ESC for colitis at a district general hospital between 1999 and 2004 were included. All patients were managed with a closed rectal (sigmoid) stump, stapled at or above the level of the pelvic brim. The stump was then either left within the 519 Management of the rectal stump after emergency sub-total colectomy J. P. Trickett et al. Table 1 Morbidity, mortality and post operative stay by surgical management of the rectal stump from previous studies. Surgical management of rectal stump Author [ref] Carter et al. [7] Kyle et al. [8] McKee et al. [9] Wojdemann et al. [10] Ng et al. [11] Mucous fistula Subcutaneous Short (intrapelvic) Combined subcutaneous and short (intrapelvic) Intraperitoneal Intraperitoneal short (intrapelvic) Level of pelvic brim Subcutaneous Case number Pelvic sepsis rate (%) Wound infection rate (%) Stump discharge rate (%) 30 55 51 106 7% 4% 12% 7% 0% 13% 12% 35% 23 53 9 147 32 8% 6% 33% 3% 3% 4% 0% 4% 0% 8% 6% 2% 0% peritoneal cavity or brought up into the subcutaneous space at the lower end of a midline laparotomy incision, secured to the fascia of the rectus sheath with interrupted dissolvable sutures and wound closure completed. The choice of surgical procedure was determined by individual surgeons’ preference, and did not relate to patients’ pre-operative morbidity or operative findings. The indications for surgery were acute colitis refractory to medical treatment, toxic megacolon or perforation. Patient data were retrospectively collected on pre-operative steroid use, inflammatory markers, albumin, indication for surgery, colonic pathology and surgical management of the rectal stump. Morbidity data were recorded on rectal stump leak, pelvic sepsis, wound infection, persistent rectal stump discharge and length of postoperative hospital stay (POS). Cases were excluded from POS analysis if complications not related to the rectal stump extended it. Mann–Whitney and Fischer exact test statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad InStat (version 3.06). Results Thirty-seven ESCs were performed, 34 for disease refractory to medical treatment, 2 for toxic mega colon and 1 for perforation. Thirty-four cases were for ulcerative colitis, 2 Crohn’s colitis and 1 infective colitis. Mortality (%) Post operative stay (days) 0% 0% 0% 14 The overall pelvic sepsis rate was 5%. The median POS was 13 days (5–193 days). Three cases were excluded from this analysis because of complications not related to the rectal stump extending POS (intracerebral haemorrhage, perforated duodenal ulcer and ileostomy complications). Twenty-seven patients were managed with an intraperitoneal and 10 a subcutaneously placed closed rectal stump. There was no pre-operative difference between the two groups in steroid use or levels of inflammatory markers. The only statistically significant difference was a lower median age and a higher albumin level in the subcutaneous group (Table 2). The only difference in indications for surgery between the two groups was one perforation in the intraperitoneal group otherwise in both groups there was one case of toxic megacolon and the remainder were cases refractory to medical treatment. The only exceptions to an open ESC with single layer stapled closure of the rectal stump were in the intraperitoneal group, 3 cases were performed laparoscopically, 5 had an additional and 3 an exclusively sutured rectal stump closure (Table 3). The exceptions to a colonic pathology of ulcerative colitis were 2 cases of Crohn’s colitis and 1 of infective colitis were also from the intraperitoneal group. The median POS for patients with a subcutaneously placed stump was shorter than for those with an intraperitoneal stump, 8 and 15 days, respectively Table 2 Pre-operative intergroup standardization by age, steroid treatment, inflammatory markers and albumin. Steroids treatment Inflammatory markers Group Age (years) % High dose Duration (days) ESR CRP WCC Albumin Intra peritoneal Subcutaneous P-value 43.5 31.5 0.017 68 75 1 13 7 0.08 35 29 0.4 39 30 0.8 9 13 0.1 24.5 32 0.01 520 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Colorectal Disease, 7, 519–522 Management of the rectal stump after emergency sub-total colectomy J. P. Trickett et al. Table 3 Method of stump closure by group. Stump closure (%) Group Stapled Sewn Both Intra peritoneal Subcutaneous 63 100 14 23 (P ¼ 0.04). Two cases excluded from this analysis were from the subcutaneous group and one from the intraperitoneal group. Two (7%) patients with UC had leakage from an intraperitoneal stump, prolonging POS (33 and 193 days); in this group there were 7 (26%) wound infections and 9 (33%) patients with persistent rectal discharge. Three (30%) of the subcutaneous stumps spontaneously opened creating a mucous fistula, in each case this resulted in a wound infection but did not appear to prolong POS (6, 7 and 16 days). No patient in this group had persistent rectal discharge. Discussion Creation of a mucous fistula was the original management of the rectal stump after ESC. A number of authors up to the late 1980s described closure of the rectal stump after ESC as hazardous because of the risk of pelvic sepsis [1,3,4]. The only author to report data of higher wound and pelvic sepsis rates for rectal stump closure attributed the poorer outcome to the more frequent use of steroid treatment [5]. There was a reduction in mortality to 3–4% for ESCs prior to the mid 1980s [1,6], when mucous fistula was advocated rather than rectal stump closure. However, this could be attributed to a variety of factors including improvements in treatment of sepsis rather than just the use of a second stoma. Carter et al. [7] in 1991 and Kyle et al. [8] in 1992 reported 7% and 8% pelvic sepsis rates from 106 and 23 cases of rectal stump closure with no mortality. The wound infection rates were 13% and 4%, respectively, and in Carter’s study, referred only to the subcutaneous closures. McKee et al. [9] reported pelvic sepsis rates of 6% for 62 closed intraperitoneal stumps, with no mortality or wound infection and a median postoperative stay of 14 days. Wojdenn et al. [10] in 1995 reported a similar rate of pelvic sepsis from 147 cases of rectal stump closed at the level of the pelvic brim and an 8% wound infection rate. The mortality rate of 2% was ascribed to sepsis related to perforation prior to surgery. We report a pelvic sepsis rate of 5% for rectal stumps closed above the level of the recto-sigmoid junction, a 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Colorectal Disease, 7, 519–522 similar rate to studies reporting no difference in pelvic sepsis between closed rectal stumps and those brought out as a mucous fistula [7]. Therefore avoidance of a second stoma can be achieved without a higher rate of pelvic sepsis (Table 1). The incidence of pelvic sepsis when the rectal stump is closed appears to be related to its location; short intrapelvic stumps have the highest rates at 33% [7], intraperitoneally placed stumps 6–12% [7,9] and subcutaneously placed stumps the lowest risk at 3–4% [7,11]. We report a 7% rate for intraperitoneally placed stumps and no pelvic sepsis associated with subcutaneously placed stumps. This lower pelvic sepsis rate in subcutaneously placed closed rectal stumps is potentially at the expense of a higher wound infection rate of 6–13% [7,11]. A strategy not employed for the study groups but with the potential to reduce post ESC sepsis is routine postoperative anal drainage of the rectal stump. A lower rate of stump discharge and pelvic sepsis has been suggested [11] for routinely drained subcutaneously placed closed rectal stumps. Greater morbidity, reflected in prolonged in-patient stay, would be expected following intraperitoneal leakage and pelvic sepsis rather than subcutaneous stump leakage or wound infection. The only previous study to compare subcutaneously with intraperitoneal closed stumps [7] reported a lower pelvic sepsis rate of 4% vs 12% but a higher wound infection rate of 13%, with more than a third having breakdown of the stump closure in the subcutaneously placed group. The two groups were managed differently, ESC and subcutaneously placed stumps were performed at a specialist tertiary referral centre, the intraperitoneally placed group however, were managed at a variety of district hospitals. No assessment of overall morbidity in terms of POS was made. We have observed a lower rate of pelvic septic complications and shorter in hospital stay for subcutaneously vs intraperitoneally placed closed rectal stumps, despite extraperitoneal stump discharge and a higher wound infection rate, thus suggesting an overall lower morbidity rate for subcutaneously placed closed rectal stumps. The infrequency of ESCs for severe colitis, means single centre studies yield too few patients to provide robust evidence of difference between techniques. Rectal stump closure is acceptable practice in ESC for severe colitis. Subcutaneous placement of a closed stump may reduce total morbidity. A randomised prospective multicentre trial incorporating postoperative anal drainage of the rectal stump is required to confirm significance. 521 Management of the rectal stump after emergency sub-total colectomy References 1 Hawley PR. Emergency surgery for ulcerative colitis. World J Surg 1988; 12: 169–73. 2 Glotzer DJ. Operations for inflammatory bowel disease: indications and type. Clin Gastroenterol 1980; 9: 371–87. 3 Fazio VW, Turnbull RB. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease of the colon. Med Clin North Am 1980; 64: 1134– 59. 4 Lee ECG, Truelove SC. Proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. World J Surg 1980; 4: 195–201. 5 Koudahl G, Aagaard P. The management of the rectal stump after subtotal colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1971; 9: 127–9. 6 Leijonmarck C-E, Brostrom O, Monsen U, Hellers G. Surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis in Stockholm county, 1955–84. Dis Colon Rectum 1989; 32: 918–26. 522 J. P. Trickett et al. 7 Carter FM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z. Subtotal colectomy for ulcerative colitis: complications related to the rectal remnant. Dis Colon Rectum 1991; 34: 1005–9. 8 Kyle SM, Steyn RS, Keenan RA. Management of the rectum following colectomy for acute colitis. Aust NZ J Surg 1992; 62: 196–9. 9 McKee RF, Keenan RA, Munro A. Colectomy for acute colitis: is it safe to close the rectal stump? Int J Colorect Dis 1995; 10: 222–4. 10 Wojdemann M, Wettergren A, Hartvigsen A, Myrhol T, Svendsen LB, Bulow S. Closure of rectal stump after colectomy for acute colitis. Int J Colorect Dis 1995; 10: 197–9. 11 Ng RLH, Davies AH, Grace RH, Mortensen NJ, McC. Subcutaneous rectal stump closure after emergency subtotal colectomy. Br J Surg 1992; 79: 701–3. 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Colorectal Disease, 7, 519–522