Cancer Cytopathology - 2001 - Chhieng - Clinical implications of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance

advertisement

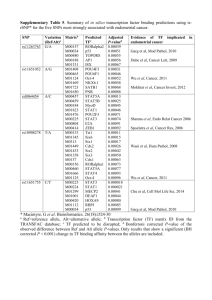

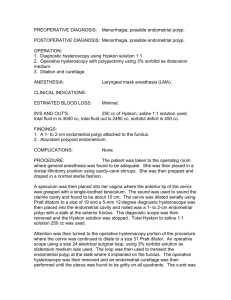

CANCER 351 CYTOPATHOLOGY Clinical Implications of Atypical Glandular Cells of Undetermined Significance, Favor Endometrial Origin David C. Chhieng, M.D.1 Paul Elgert, C.T.2 Jean-Marc Cohen, M.D.3 Joan F. Cangiarella, M.D.4 1 Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama. 2 Cytopathology Laboratory, New York University Medical Center, New York, New York. 3 Department of Pathology, Beth Israel Medical Center, New York, New York. 4 Department of Pathology, New York University Medical Center, New York, New York. BACKGROUND. The Bethesda System recommends qualifying atypical glandular cells with regard to their possible origin: endocervical versus endometrial. This study was undertaken to determine the clinical significance of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance that favor an endometrial origin (AGUS-EM). METHODS. A computer search identified 62 cervicovaginal smears (5.25% of all smears classified as AGUS) with a diagnosis of AGUS-EM in the files of Shared Cytopathology Laboratory of New York University Medical Center/Bellevue Hospital Medical Center between January 1995 and December 1999. The patients ranged in age from 29 years to 88 years (mean age, 53 years). Thirty-four patients were postmenopausal (55%), and 5 patients were on hormonal replacement therapy. Follow-up was available for 56 patients (90%); 45 patients (73%) underwent biopsy, and 11 patients (17%) had repeat cervicovaginal smears. Six patients were lost to follow-up. RESULTS. Among patients who underwent biopsy, 14 patients (31%) had a clinically significant uterine lesions, including 6 (13%) endometrial adenocarcinomas, 5 (11%) endometrial hyperplasias, and 3 (7%) squamous lesions (2 high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and 1 squamous cell carcinoma). Ten of 11 patients with significant endometrial pathology findings were postmenopausal. The remaining 31 patients had benign pathology results, which included chronic cervicitis, endometritis, endometrial polyps, microglandular hyperplasia, and tubal metaplasia. Among the patients with repeat cervicovaginal smears, one patient had atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; the remaining patients were within normal limits. CONCLUSIONS. Approximately one-third of women with a diagnosis of AGUS-EM had a significant uterine lesion on subsequent biopsy; the majority of these lesions were endometrial in origin. Patients with a diagnosis of AGUS-EM on cervicovaginal smears should be followed closely, and endometrial curettage or biopsy should be included in their initial work-up. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 2001;93:351– 6. © 2001 American Cancer Society. KEYWORDS: cervicovaginal smears, atypical, glandular cells, endometrial cells, postmenopause, adenocarcinoma. Presented at the 48th annual meeting of the American Society of Cytopathology, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November, 7–11, 2000. Address for reprints: David C. Chhieng, M.D., Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, KB 627 619 19 Street S, Birmingham AL 35249-6823; Fax: 205-975-7284; Email: dchhieng@path.uab.edu. Received December 28, 2000; revision received June 14, 2001; accepted June 28, 2001. © 2001 American Cancer Society DOI 10.1002/cncr.10139 T he diagnostic category atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS) was introduced by the Bethesda System in 1988 to denote cytologic changes in glandular cells that exceed those typical of reactive changes but are quantitatively and/or qualitatively not diagnostic of adenocarcinoma.1 These changes may represent a florid response to inflammation, a precursor neoplastic lesion, or a nonrepresentative sampling of a neoplastic lesion. The Bethesda system also recommends subclassifying the atypical glandular cells according to their possible anatomic origin: endocervical versus endometrial.2 There have been a number of studies addressing the 352 CANCER (CANCER CYTOPATHOLOGY) December 25, 2001 / Volume 93 / Number 6 TABLE 1 Criteria of Atypical Glandular Cells, Favor Endometrial Origin Arranged in loose and tight clusters Scant cytoplasm Nuclear enlargement ⫹/⫺ Hyperchromasia ⫹/⫺ Nucleoli ⫹/⫺ Irregular nuclear contours ⫹/⫺: With or without. implications and management of patients with AGUS in general as well as patients with AGUS, favor endocervical origin in particular.3–17 Little is known about the clinical significance of AGUS, favor endometrial origin (AGUS-EM). In this retrospective study, we determined the rate of a diagnosis of AGUS-EM and the incidence of clinically significant lesions in women with this cytologic diagnosis on subsequent follow-up. We also suggested guidelines for the clinical management of patients with this diagnosis. MATERIALS AND METHODS From January 1995 to December 1999, 211,220 cervicovaginal smears were screened at the Shared Cytopathology Laboratory at New York University Medical Center/Bellevue Hospital Medical Center. All cervicovaginal smears were collected using an endocervical brush, an Ayre spatula, or a cervical brush. One or two slides per patient were prepared, depending on the preferences of the health care providers who obtained the smears. All smears were fixed immediately with nonaerosal spray fixative and sent to the cytopathology laboratory. Patients with a cytologic diagnosis of AGUS-EM, were identified during the study period. Patients with benign appearing endometrial cells were excluded. The diagnoses were made by staff pathologists using the criteria listed in Table 1. Information regarding previous gynecologic history and hormone replacement therapy was obtained. The methods and results of patient evaluation, which included repeat cervicovaginal smears, colposcopic examination along with endocervical curettage and/or cervical biopsy, and endometrial biopsy, were reviewed and recorded. Follow-up smears were obtained 6 –12 months after the initial abnormal smear; all biopsies and curettages were performed within 1 year. RESULTS During the 5-year study period, 1179 cervicovaginal smears (0.56%) had a cytologic diagnosis of AGUS. TABLE 2 Biopsy Methods Methods No. of patients (%) EMB and ECC EMB only ECC only Cervical biopsy and ECC Cervical biopsy, ECC, and EMB Cervical biopsy Vaginal biopsy Total 17 (38) 21 (47) 1 (2) 3 (7) 1 (2) 1 (2) 1 (2) 45 (100) EMB: endometrial biopsy; ECC: endocervical curettage. Among these smears, 62 (5.25%) had a diagnosis of AGUS-EM. The mean age of this group of patients was 53 years, with a range of 29 – 88 years. Thirty-four patients (55%) were postmenopausal. Five of 34 patients (15%) were receiving hormone replacement therapy at the time of the AGUS diagnosis. Seven patients presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding: Six patients were postmenopausal, and one patient was premenopausal. One patient had a history of endometrial adenocarcinoma and was status posthysterectomy. An additional patient presented with a history of an ovarian mucinous neoplasm of low malignant potential. Follow-up information was available for 56 patients (90%): Forty-five patients (73%) had histologic follow-up, and 11 patients (17%) had repeat cervicovaginal smears. Six patients were lost to follow-up. The types of procedures performed for patients who underwent histologic evaluation are shown in Table 2. All but six patients underwent endometrial biopsy. The patient who was status posthysterectomy for endometrial carcinoma had biopsy of the vaginal cuff. Fourteen of 45 patients (31%) with subsequent histologic follow-up had a clinically significant uterine lesion that was defined as a preneoplastic or neoplastic, glandular or squamous lesion. Eleven patients (24%) had a glandular lesion, including 6 endometrial adenocarcinomas (Fig. 1) and 5 endometrial hyperplasias. Three patients (7%) had squamous lesions, including two high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (Fig. 2) and one invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Table 3 shows the results of histologic diagnoses in relation to the patients’ hormonal status. Ten of 11 patients with significant endometrial pathology and all patients with squamous lesions were postmenopausal. In addition, four of five patients who presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding and underwent histologic evaluation had significant endometrial lesions. The remaining 31 patients with biopsies had Significance of AGUS, Favor Endometrial Origin/Chhieng et al. 353 TABLE 3 Results of Histologic Follow Up and Menopausal Status Histologic diagnosis Postmenopausal Premenopausal Total Significant uterine lesions Endometrial carcinoma Endometrial hyperplasia SCC or HGSIL Benign pathology Total 13 6 4 3 14 27 1 0 1 0 17 18 14 6 5 3 31 45 SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; HGSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. FIGURE 1. Three-dimensional cluster of glandular cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant-to-moderate, sometimes vacuolated cytoplasm. Endometrial biopsy revealed a well-differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma (Papanicolaou stain; original magnification, ⫻600). FIGURE 2. Haphazardly arranged glandular cells with coarse chromatin and FIGURE 3. A large, three-dimensional group of glandular cells with mild nuclear crowding and overlapping as well as mild nuclear hyperchromasia. Subsequent biopsy revealed marked chronic endometritis (Papanicolaou stain; original magnification, ⫻600). an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. It was determined that the patient had a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion that involved the endocervical gland (Papanicolaou stain; original magnification, ⫻600). benign pathology that included chronic cervicitis with squamous metaplasia, endometritis (Fig. 3), endometrial polyps, mircoglandular hyperplasia (Fig. 4), and tubal metaplasia. None of them demonstrated any significant endocervical lesions. Among the patients with repeat cervicovaginal smears, one patient had a diagnosis of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. The repeat smears of the remaining 10 patients were interpreted as within normal limits or as benign cellular changes. Among all patients with an AGUS diagnosis, 62% underwent histologic evaluation. Twenty-nine percent had a significant uterine lesion on subsequent followup: Twenty-two percent were squamous lesions, 2% were endocervical lesions, and 5% were endometrial lesions. FIGURE 4. A small cluster of glandular cells with scant cytoplasm and mild nuclear hyperchromasia and pleomorphism. Subsequent biopsy revealed microglandular hyperplasia; the patient was on hormone replacement therapy (Papanicolaou stain; original magnification, ⫻600). 354 CANCER (CANCER CYTOPATHOLOGY) December 25, 2001 / Volume 93 / Number 6 DISCUSSION Since the introduction of the diagnostic category AGUS by the Bethesda System in 1988, there have been a number of studies addressing the incidence and the clinical significance of AGUS.3–17 The reported rates of AGUS among the general patient population ranged from 0.17% to 1.83%. Most laboratories report an AGUS rate ⬍ 1%.3–17 The AGUS rate of 0.56% observed among the general patient population in our laboratory was in agreement with the current literature. Few studies have investigated the incidence of atypical endometrial cells in cervicovaginal smears. One study was carried out by Cherkis et al.18 before the introduction of the Bethesda system. Those authors identified 177 women with atypical endometrial cells from a screening pool of approximately 300,000 cervicovaginal smears, resulting in a frequency of 1 in 1700 or 0.06%. In another study, the incidence of atypical endometrial cells was 6.2% (5 of 81 smears) among all cervicovaginal smears with a diagnosis of AGUS.19 In a more recent study, Soofer and Sidaway17 reported that the incidence of atypical endometrial cells was 12% among all AGUS smears and 0.01% among all cervicovaginal smears screened during the study period. In the current study, atypical endometrial cells accounted for 5.25% of smears with a diagnosis of AGUS or 0.03% of all smears screened in our laboratory during the study period, findings consistent with those in the literature. It is interesting to note that many studies did not subclassify the origin of the atypical glandular cells according to their possible anatomic site. Thirty-one percent of our patients with histologic follow-up had a significant uterine lesion; 11 lesions (24%) were of endometrial origin, and 3 lesions (7%) were of squamous origin. These findings are similar to those reported by Cherkis et al.18: 32 of 134 patients (31.1%) with atypical endometrial cells had a significant uterine lesion. Duska et al.19 also reported that 2 of 5 patients (40%) with atypical endometrial cells had a significant uterine lesion on subsequent follow-up. In both studies, the significant uterine lesions were exclusively of endometrial origin. Soofer and Sidaway,17 in a different study, identified 2 (18%) significant uterine lesions, 1 high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL), and 1 endometrial lesion in 11 patients with atypical endometrial cells. The incidence of a significant endometrial lesion (either hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma) on subsequent follow-up when normal endometrial cells were identified in the preceding cervicovaginal smears ranged from 10.5% to 24.1%, with an average of 14.8%.20 –23 Therefore, the incidence of a significant uterine lesion on subsequent follow-up is higher for patients with atypical endometrial cells on their cervicovaginal smears compared with patients with smears that show normal endometrial cells. In a previous study, we reported that 75% of the significant uterine lesions that were identified after a diagnosis of AGUS were of squamous origin.3 In the current study, the majority of significant uterine lesions (79%) were endometrial in origin after a diagnosis of atypical endometrial cells. This may be explained by the fact that patients with atypical endometrial cells tended to be older (average age, 53 years vs. 45 years in a previous study3) and were more likely to be postmenopausal (55% vs. 40% in a previous study3) compared with patients who were diagnosed with AGUS. Similar observations were made by other authors.18,19 Cherkis et al.18 reported that all of the significant uterine lesions after a diagnosis of atypical endometrial cells were of endometrial origin. Therefore, our findings and findings from other reports justify the subclassification of AGUS-EM. Twenty-seven of 45 postmenopausal women (60%) with atypical endometrial cells had a significant uterine lesion on subsequent follow-up, whereas 1 of 18 premenopausal women (6%) with atypical endometrial cells had a significant uterine lesion on followup. There was a 10-fold increase in the frequency of significant uterine lesions in postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women. The difference was statistically significant (P ⬍ 0.003; Fisher exact test). Other authors also have observed an increased incidence of endometrial adenocarcinoma associated with increasing age in patients with atypical endometrial cells.18 Patients age ⬎ 59 years were more likely to have an endometrial adenocarcinoma than patients age ⬍ 59 years, with a relative ratio of 2.3. In the current study, among the five patients who presented with vaginal bleeding and had histologic follow-up, four women were postmenopausal and had either endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma after a diagnosis of atypical endometrial cells in cervicovaginal smears. The remaining patient was premenopausal and had an endometrial polyp on histologic evaluation. It is not surprising that symptomatic postmenopausal women with atypical endometrial cells were at risk of harboring a significant endometrial lesion. It is more important to note that more than half (64%) of the patients with significant endometrial lesions were asymptomatic. The cytologic finding of atypical endometrial cells triggered a subsequent work-up, resulting in the identification of the occult endometrial lesions. Three of our patients with atypical endometrial Significance of AGUS, Favor Endometrial Origin/Chhieng et al. cells had an HGSIL or invasive squamous cell carcinoma on follow-up. Other authors also have reported the finding of HGSIL on follow-up of a patient with AGUS-EM.17 HGSIL often is characterized by the presence of three-dimensional, hyperchromatic, crowded groups that can mimic endometrial cells.24 In a recent study, Zhou et al.25 reported that small cell carcinoma of the cervix can form ball-like clusters of cells with scant cytoplasm resembling endometrial cells. The finding of dysplastic squamous cells should provide evidence that the hyperchromatic, crowded groups most probably are of squamous origin.24 In addition, the identification of a squamous cervical lesion does not necessarily preclude the possibility of a concurrent endometrial lesion. Various investigators have attempted to qualify the diagnosis of AGUS to favor a reactive/benign process or a premalignant/malignant condition.11,26 –31 The majority of these studies focused on atypical glandular cells of endocervical origin, particularly the criteria for separating endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ from benign lesions. There was only one study that attempted to subclassify atypical endometrial cells into three categories based on the nuclear size and hyperchromasia, chromatin pattern, and presence or absence of nucleoli.18 Those authors reported that 40% of patients with markedly atypical endometrial cells, 20% of patients with moderately atypical endometrial cells, and none of the patients with mildly atypical endometrial cells had an endometrial carcinoma on follow-up, with a risk ratio of 1.7. Both the Bethesda System and the International Academy of Cytology Task Force did not recommend the subclassification of atypical endometrial cells because of the lack of well-defined criteria.2,32 Therefore, it is our routine practice not to qualify further the atypical endometrial cells according to whether they favor a reactive or neoplastic process. Ronnett et al.33 have assessed the value of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing in the management of patients with cervicovaginal smears classified as AGUS.33 HPV testing identified 92% of women with histologically confirmed HGSIL, all patients with endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ, but none of the patients with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Therefore, HPV DNA testing did not provide useful information for evaluating the status of the endometrium. Currently, there is no clear consensus regarding the management of patients with atypical endometrial cells. Based on the findings of our study, we would like to suggest the following guidelines: A complete endometrial evaluation should be included as part of the initial examination, particularly for postmenopausal women. Colposcopic examination with endocervical 355 curettage should be considered part of the initial examination, because a small but significant number of patients can have a high-grade squamous lesion. Asymptomatic premenopausal patients may be followed conservatively. In patients with an otherwise negative initial histologic evaluation and persistent glandular atypia on repeat cervicovaginal smears, the clinician should consider more aggressive evaluation.3,18,19 It cannot be overemphasized that communication between clinicians and cytopathologists must be established to convey the degree of concern about possible neoplasia for a cytologic interpretation of AGUS-EM. In summary, the incidence of atypical endometrial cells was low: 5.25% of all AGUS smears diagnosed in our laboratory. About one-third of these patients had a significant uterine lesion on follow-up, with the majority of endometrial origin. Close follow-up is indicated in patients with a cytologic diagnosis of AGUS-EM. REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Anonymous. The 1988 Bethesda System for reporting cervical/vaginal cytological diagnoses. National Cancer Institute Workshop. JAMA 1989;262(7):931– 4. Kurman R, Solomon D. The Bethesda System for reporting cervical/vaginal cytologic diagnoses: definitions, criteria and explanatory notes for terminology and specimen adequacy. New York: Springer-Verlag, Inc., 1994. Chhieng DC, Elgert PA, Cangiarella JF, Cohen JM. Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. A follow-up study from an academic medical center. Acta Cytol 2000;44(4):557– 66. Eddy GL, Ural SH, Strumpf KB, Wojtowycz MA, Piraino PS, Mazur MT. Incidence of atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance in cervical cytology following introduction of the Bethesda System. Gynecol Oncol 1997;67(1):51–5. Eddy GL, Strumpf KB, Wojtowycz MA, Piraino PS, Mazur MT. Biopsy findings in five hundred thirty-one patients with atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance as defined by the Bethesda system. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177(5): 1188 –95. Gornall RJ, Singh N, Noble W, Boyd IE, Hitchcock A. Glandular abnormalities on cervical smear: a study to compare the accuracy of cytological diagnosis with underlying pathology. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2000;21(1):49 –52. Kennedy AW, Salmieri SS, Wirth SL, Biscotti CV, Tuason LJ, Travarca MJ. Results of the clinical evaluation of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGCUS) detected on cervical cytology screening. Gynecol Oncol 1996; 63(1):14 – 8. Kim TJ, Kim HS, Park CT, Park IS, Hong SR, Park JS, et al. Clinical evaluation of follow-up methods and results of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS) detected on cervicovaginal Pap smears. Gynecol Oncol 1999;73(2):292– 8. Manetta A, Keefe K, Lin F, Ahdoot D, Kaleb V. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance in cervical cytologic findings. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180(4):883– 8. 356 CANCER (CANCER CYTOPATHOLOGY) December 25, 2001 / Volume 93 / Number 6 10. Schindler S, Pooley RJ Jr., De Frias DV, Yu GH, Bedrossian CW. Follow-up of atypical glandular cells in cervical-endocervical smears. Ann Diagn Pathol 1998;2(5):312–7. 11. Lee KR, Manna EA, St John T. Atypical endocervical glandular cells: accuracy of cytologic diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol 1995;13(3):202– 8. 12. Nasu I, Meurer W, Fu YS. Endocervical glandular atypia and adenocarcinoma: a correlation of cytology and histology. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1993;12(3):208 –18. 13. Goff BA, Atanasoff P, Brown E, Muntz HG, Bell DA, Rice LW. Endocervical glandular atypia in Papanicolaou smears. Obstet Gynecol 1992;79(1):101– 4. 14. Bose S, Kannan V, Kline TS. Abnormal endocervical cells. Really abnormal? Really endocervical? Am J Clin Pathol 1994;101(6):708 –13. 15. Cenci M, Mancini R, Nofroni I, Vecchione A. Endocervical atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. II. Morphometric and cytologic analysis of nuclear features useful in characterizing differently correlated subgroups. Acta Cytol 2000;44(3):327–31. 16. Cenci M, Mancini R, Nofroni I, Vecchione A. Endocervical atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. I. Morphometric and cytologic characterization of cases that “cannot rule out adenocarcinoma in situ.” Acta Cytol 2000; 44(3):319 –26. 17. Soofer SB, Sidawy MK. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance: clinically significant lesions and means of patient follow-up. Cancer 2000;90(4):207–14. 18. Cherkis RC, Patten SF Jr., Dickinson JC, Dekanich AS. Significance of atypical endometrial cells detected by cervical cytology. Obstet Gynecol 1987;69(5):786 –9. 19. Duska LR, Flynn CF, Chen A, Whall-Strojwas D, Goodman A. Clinical evaluation of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance on cervical cytology. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91(2):278 – 82. 20. Gondos B, King EB. Significance of endometrial cells in cervicovaginal smears. Ann Clin Lab Sci 1977;7(6):486 –90. 21. Cherkis RC, Patten SF Jr., Andrews TJ, Dickinson JC, Patten FW. Significance of normal endometrial cells detected by cervical cytology. Obstet Gynecol 1988;71(2):242– 4. 22. Kerpsack JT, Finan MA, Kline RC. Correlation between endometrial cells on Papanicolaou smear and endometrial carcinoma. Southern Med J 1998;91(8):749 –52. 23. Gomez-Fernandez CR, Ganjei-Azar P, Capote-Dishaw J, Averette HE, Nadji M. Reporting normal endometrial cells in Pap smears: an outcome appraisal. Gynecol Oncol 1999; 74(3):381– 4. 24. DeMay R. The art and science of cytopathology, vol I. Chicago: ASCP Press, 1995. 25. Zhou C, Hayes MM, Clement PB, Thomson TA. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: cytologic findings in 13 cases. Cancer 1998;84(5):281– 8. 26. DiTomasso JP, Ramzy I, Mody DR. Glandular lesions of the cervix. Validity of cytologic criteria used to differentiate reactive changes, glandular intraepithelial lesions and adenocarcinoma. Acta Cytol 1996;40(6):112–-35. 27. Raab SS, Isacson C, Layfield LJ, Lenel JC, Slagel DD, Thomas PA. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. Cytologic criteria to separate clinically significant from benign lesions. Am J Clin Pathol 1995;104(5):574 – 82. 28. Zweizig S, Noller K, Reale F, Collis S, Resseguie L. Neoplasia associated with atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance on cervical cytology. Gynecol Oncol 1997;65(2): 314 – 8. 29. Burja IT, Thompson SK, Sawyer WL Jr., Shurbaji MS. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance on cervical smears. A study with cytohistologic correlation. Acta Cytol 1999;43(3):351– 6. 30. Siziopikou KP, Wang HH, Abu-Jawdeh G. Cytologic features of neoplastic lesions in endocervical glands. Diagn Cytopathol 1997;17(1):1–7. 31. Roberts JM, Thurloe JK, Bowditch RC, Laverty CR. Subdividing atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance according to the Australian modified Bethesda, system: analysis of outcomes. Cancer 2000;90(2):87–95. 32. Solomon D, Frable WJ, Vooijs GP, Wilbur DC, Amma NS, Collins RJ, et al. ASCUS and AGUS criteria. International Academy of Cytology Task Force summary. Diagnostic cytology towards the 21st century: an international expert conference and tutorial. Acta Cytol 1998;42(1):16 –24. 33. Ronnett BM, Manos MM, Ransley JE, Fetterman BJ, Kinney WK, Hurley LB, et al. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS): cytopathologic features, histopathologic results, and human papillomavirus DNA detection. Hum Pathol 1999;30(7):816 –25.