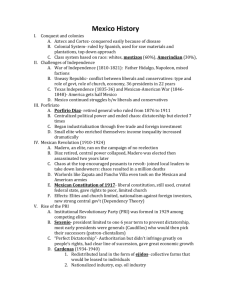

Political Parties in Mexico Name; Lavender Awuor Otieno Institution Affiliate; Perfect Solution Date; 26th March Historical Roots of Mexican Politics Like any other part of the world, politics play a major role in governance in Mexico. Since the end of the one-party rule, which significantly ended in the 2000 presidential election, the dynamics of Mexican politics have gradually changed. Mexico is headed by a president elected after every six years and serves for one term only. The legislature is also largely controlled by politics. The Mexican legislature is bicameral, with 128 senators (upper chamber) and 500 deputies (Lower Chamber). Three hundred deputies are elected through a popularity vote, while the remaining 200 are elected through a proportional representation based on a political party's share of total votes. The politics in Mexico is largely influenced by political factors, especially in the neighboring United States of America. Any policy Mexico has to make; has to consider the American views or position. Mexicans even joke about it by saying, "So far from God, so close to the United States ."In most instances, the US influence in Mexican politics is not positive. This is a problem that began haunting Mexico almost immediately after gaining independence. After gaining independence in 1821, Mexico was a vast country that included all of the southwest and much of the west of the current USA. Mexico emerged bankrupt from independence, and most foreign governments, including the US, invaded and took control of roughly half of the country. During this time, Mexico was being led by Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, who was only good at shifting political allegiance to the side that favored him. This prompted the war of reform between 1857-1861, which was won by liberals under the leadership of Benito Juarez. The liberals dominated Mexican politics, but there was no stability. The Mexican state later solidified under Porfirio Diaz, putting Mexico back to its economic feet. Diaz also established a lengthy period of internal peace and offered benefits to all major social and political groups. Eventually, the flavors combined with no accountability led to a political conflict over time. Diaz also wanted to remain in power and conducted a fraudulent election in 1910, leading to the Mexican revolution. Diaz was forced to resign and flee Mexico in 1911, leaving turmoil that lasted until 1917, when Venustiano Carranza became president after two regimes had led the country after Diaz. Contemporary Politics and Birth of Political Parties in Mexico After the revolutionary war, many military heroes became presidents. They depoliticized the armed forces by granting them generous budgets and stayed out of internal military decisions. Subsequently, the labor unions controlled by the government did not become radical as experienced in other Latin American nations. This allowed the political system to stay stable, leading to the birth of the first political party, the National Revolution Party (PNR), in 1929, which was later changed to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in 1946. PRI has dominated Mexican politics and two other political parties: National Action Party (PAN) and the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA). Let's explore each party further to understand their role in Mexican politics better. The Institutional Revolution Party (PRI) In Spanish Partido Revolucionario Institucional, the institutional revolution party was the first Mexican political party that dominated Mexican politics from its formation in 1929 to the end of the 20th century. The party was originally called Partido Revolucionario Nacional (National Revolutionary Party), later renamed to Mexican Revolutionary Part in 1938 before taking its current name in 1946. PRI was so dominant and influential that virtually all prominent political figures in Mexico belonged to the party, from national to local politics. A nomination of a candidate was almost a guarantee of being elected. The PRI party was founded by Plutarco Elias Calles, who became the Mexican president just as the revolutionary war was concluding. During this time, the government had constant conflicts with the United States, the Catholic Church, and rebellion in the military. He sought more stability in government by seeking a coalition of local and regional politicians and labor and peasant leaders. The party aimed to shift power to state party units and sectors that represented the urban laborers, peasants, civil servants, artisans, women, youth, and military (Mantilla, 2019). In the 1940s, the party disbanded its military wing and encouraged members to join other sectors making it even more popular. The party began experiencing some downfalls in the 1970s when it was accused of suppressing student protests. It was largely accused of fraudulent elections in the 1980s and 1990s, leading to Mexicans challenging its political monopoly. The opposition parties ganged up against it as they garnered several seats in the Chamber of Deputies. The party still remained in power but continued to lose more seats to the opposition in the subsequent elections. For instance, in the 1988 elections, the party lost four senate seats to the opposition, the first time it had lost a senate seat in 59 years. Their presidential candidate, Carlos Salinas, also won with a narrow margin and the opposition believed the election was rigged. Although the PRI party remained in power for several more years, its popularity had gradually declined all over the country. The party lost several gubernatorial seats, including the mayor of Mexico City in 1997. In the 1994 presidential elections, PRI's Ernesto Zedillo won with another narrow margin. During his reign, PRI lost the majority seats in the legislature for the first time. Zedillo even declined to name his successor in the 2000 elections, which was the norm of his predecessors. The PRI's candidate in the 2000 election eventually lost to the National Action Party's (PAN) candidate, bringing to an end the 70-year rule of the PRI. However, the party remained active in Mexican politics. In 2009, the party regained the majority seats in the legislature, and in 2012 Enrique Pena Nieto of PRI won the presidential elections welcoming back the party’s rule after 12 years of absence in ruling (Flores-Macías, 2013). The 2012 elections marked a mature democracy in Mexico as the elections were not contested as had happened in the 2006 elections. Other political observers feared that Mexico would plunge into the previous PRI regime, which would hurt the country's democracy. Would the PRI administration hurt the democracy installed by the National Action Party’s (PAN) administration? The National Action Party (PAN) The second party to rule Mexico for a longer period is the PAN. The National Action Party, Spanish Partido Accion Nacional, was founded in 1939. The founders had close ties with the Roman Catholic Church, and they sought to represent their interests. The church had been stripped of its legal recognition in 1917. The PAN was the main opposition party to the ruling PRI for a long time. The party first contested against the PRI in 1943 but could not beat the ruling party until later in the 1980s. In the 1980s, the party was fed up with the continuous sabotage of elections by the ruling party. Some members suggested conciliation and compromise, but the agitated ones opted for greater confrontations against the PRI. The party won its first governorship position in 1989 after capturing the Baja California Norte state (Mantilla, 2019). In the 1990s, President Salinas of the PRI awarded the Guanajuato governorship position to the party to win its cooperation in the legislature. The party's resolution to back the PRI cost it in elections as some locales were opposed to the reforms brought forth by the government. In the subsequent elections, the PAN's representation in the Chamber of Deputies continued to expand, and its performance in the presidential elections. The party won a quarter of national votes in legislative elections making the PRI lose the absolute majority for the first time. In the 2000 presidential elections, Vicente Fox, the party's candidate, won, defeating the PRI for the first time. The party also formed the largest bloc in the Chamber of Deputies alongside its coalition partners. The party also won the 2006 presidential elections through Felipe Calderon. Calderon resolved to use the military to fight drug cartels, beginning the part's downfall. Mexico was thrown into gruesome violence. The ongoing recession in the country, drug warfare, high unemployment, and crime rates in Mexico made the party lose its popularity and rule back to the PRI in the 2009 legislative elections and 2012 presidential elections. In 2018, the party lost the presidency to the incumbent AMLO of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA). The National Regeneration Movement Alliance (MORENA) The National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), Spanish Movimiento Regeneration Nacional, was formed in 2011 by the current Mexican President, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, commonly known as AMLO. The party began as an NGO before being formally registered as a political party in 2014. AMLO formed the party to protest against the power mafia policies, political corruption, and election frauds (Mantilla, 2019). AMLO had run for president with the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) in 2012, which he left after losing to PRI. He claimed that the PRD party had collided with the PRI and betrayed the Mexican people. He formed the MORENA movement before turning it into a political party. The party participated in the 2015 legislative elections for the first time and won several seats in the Chamber of Deputies. In the 2018 presidential elections, MORENA entered into a coalition with two small parties and won the election. Observers attribute MORENA’s win to the ability of AMLO to tap a deep vein of voter frustration with inequality, poverty, corruption, and violence which both PRI and PAN had struggled to offer credible solutions (Greene & SánchezTalanquer, 2018). AMLO campaigned all over Mexico urging voters to choose change over 'more of the same conditions. References Flores-Macías G. (2013). Mexico's 2012 Elections: The Return of the PRI. Journal of Democracy, 21(1), 128-141. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2013.0006 Greene K., & Sánchez-Talanquer M. (2018). Latin America’s Shifting Politics: Mexico’s Party System Under Stress. Journal of Democracy, 29(4), 3142. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0060 Mantilla, L. F. (2019). Religion and political parties in Mexico. The Routledge Handbook to Religion and Political Parties, 213-223. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351012478-18