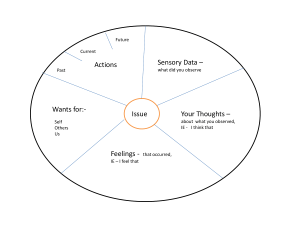

PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit Reframing “faux feelings” Emotions Exercise 20 min Client No At times, --descriptions of how a client is feeling are being tainted by a sense of judgment or criticism by another person or circumstance. These “feelings” are considered faux feelings because they do not describe the client’s true feelings but rather reflect the client’s thoughts about what caused the feeling (e.g., the actions of another person). The English language is notorious for confusing thoughts and feelings. Although grammatically correct, none of the following sentences expresses feelings: “I feel hassled,” “I feel insulted,” and “I feel criticized.” These are faux feelings, that is, thoughts masquerading as feelings. Words that are followed by an explicit or implicit “by him/her/ them/it” are a good indication of a faux feeling, such as attacked, belittled, criticized, intimidated, manipulated, and intimidated (e.g., “I feel intimidated by them”). These words sound like feelings but imply that someone or something was the cause of a negative event or outcome. There is an emotional charge that comes with ascribing blame (for a review, see Tennen & Affleck,1990), and as such, faux feelings communicate a judgmental attribution. It is as though the clients are not taking full ownership of how they truly feel, possibly because it is more painful and requires greater vulnerability to acknowledge this truer, deeper emotion. Projecting feelings outward is far less painful than looking inward and taking responsibility for one’s feelings. Helping clients separate the judgment and mental interpretation of a faux feeling from the true feeling is an important skill, as suggested by the non-violent communication model (1983, 2003). When clients learn to master this skill, there is less room for blaming others and more room for finding solution, self-awareness, and growth. Author This tool was created by Dr. Hugo Alberts and Dr. Lucinda Poole. [1] PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit Goal This tool aims to help clients understand (1) the difference between a faux feeling and a true feeling and (2) the existence of unmet psychological needs. Rather than blaming others for their feelings, clients can thus learn to take responsibility for these feelings. Moreover, the inward focus that is promoted by seeing through faux feelings helps clients resolve conflicts more effectively by communicating about their true feelings and needs instead of criticizing others. Advice ■ Practitioners may pick up on a client using faux feelings if the therapy session begins to feel like a gossip or gripe session. Such conversations fail to expand understanding, bolster motivation, or facilitate growth, and so should be limited whenever possible. ■ It is not uncommon for practitioners to get involved in the client’s judgmental narrative and feel obliged to respond with affirming statements, such as, “What a terrible thing to do!” These statements are unhelpful as they strengthen the client’s belief in an external cause for their emotions. Rather, the practitioner is advised to tap into the emotion that the client experienced. For example, the practitioner may ask, “What did you feel in your body when this happened?” and “It sounds like you experienced anger, is that right?” In this way, attention is shifted from a mental interpretation of the event to the subjective experience of the event. ■ Clients who frequently use faux feelings tend to perceive their emotions as being at the mercy of others. They often feel that others are responsible for how they feel. These clients need to learn to shift attention from the believed cause of their feelings (the other person) to the experience of the feeling. This process involves shifting from the identification with thoughts (attributions) to the experience of emotions. Mindfulness practice, where clients learn to observe thoughts and connect to the bodily experience of the emotion, can be a powerful tool in this respect. ■ When clients use faux-feeling words to describe how they feel, they often have a solution or strategy in mind that involves a desire to control or require something from someone else (an implicit “should”). For example, a client who states, “I feel criticized (by someone)” may imply “he/she should let me know that he/she appreciates my talents.” This form of control is often unhelpful as it reduces the client’s autonomy: the client believes that the solution for his or her emotion is to be found outside the self. When others behave in the way the client expects them to behave, the emotion is believed to be resolved. Other people may not behave in expected ways, and thus the clients remain dependent on their course of action. The practitioner may familiarize the clients with the concept of control and help them distinguish between factors that are within and outside personal control. The tool “Dealing with Uncontrollable Circumstances” in the “Positive Psychology Toolkit” can be used for this purpose. [2] PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit ■ It is important to note that the goal of making clients aware of faux feelings is not to correct them for incorrectly naming their feelings. The clients’ judgments and evaluations are real thoughts interlaced with real feelings and needs. Rather, the practitioner is advised to use faux feelings to point the clients’ attention to the feelings and needs that lie beneath them. In this way, the practitioner may help the client address the needs that the emotion signals autonomously, rather than using controlling or requiring something from someone else. The tool “Personal Needs Meditation” in the “Positive Psychology Toolkit” can be used for this purpose. ■ Clients need to realize that seeing through faux feelings does not mean one refrain from sharing the causal attribution of the feeling with the other person. They may still decide to tell the other person how their actions came across. For example, a client who indicates to feel “disrespected” may still inform the other person about this interpretation. Importantly, the client recognizes that “disrespected” is a personal interpretation (thoughts) about the situation, not a feeling or a description of the facts. Clients may benefit from learning to express their thoughts to others in a way that stresses awareness of their subjective nature. In the above-described example, a client may say, “When you don’t clean up your mess like you did yesterday, I sometimes think that you don’t respect me.” References ■ Rosenberg, M.B. (1983). A model for nonviolent communication. New Society Publishers. ■ Rosenberg, M.B. (2003). Nonviolent communication: A language of life. Puddledancer Press. ■ Tennen, H., & Affleck, G. (1990). Blaming others for threatening events. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 209-232. [3] PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit Reframing “faux feelings” In this exercise, we are going to look at difficult feelings and explore what your feelings may tell you about what you need. Specifically, we are going to look at feelings that involve other people. Step 1: Recalling past feelings Read through the feelings listed in the first column (Faux Feeling) of the Faux Feelings Table in Appendix A. For each feeling, recall a time when you experienced this feeling. Take your time here, as these memories might take a little while to come back to you. Then, in the second column (Past Experience), detail the situation or circumstance that led to this feeling. A completed example is included in the first row of the table. Note, if you cannot remember a time when you felt this way, simply leave the row blank and move on to the next feeling. Step 2: Understanding faux feelings vs. true feelings When trying to describe how we feel, we often use words that are not describing our true feelings. For example, when you say, “I feel attacked,” this may sound like a feeling, but it is your interpretation of what happened. By saying, “I feel attacked,” you are not referring to your feelings but to what you think happened: you think the other person attacked you. Whether the other person attacked you or not, the point is that “attacked” does not describe how you feel. Instead, it is telling you something about how you perceived the situation: it is a thought, a judgment disguised as a feeling. These “fake” labels for feelings are called “faux” feelings. A good way to recognize a faux feeling is when the word to describe your feelings can be followed by “by him/her/them/it.” For example, “I feel attacked [by him]” or “I feel manipulated [by them].” Simply put, another person causes a faux feeling. If “attacked” is not a true feeling, then what is a true feeling when you think someone is attacking you? To know your true feeling, you must look inward. Rather than focusing on the situation or the other person, you must focus on yourself—on what you experience. Perhaps you feel scared or angry. Those are true feelings. Now with this in mind, let us look closely at your previously listed experiences and see whether we can go a little deeper into how you felt at that moment. How did you truly feel back then? You might like to close your eyes for a minute, put yourself back in that moment, and try to relive it again. Allow yourself to visualize where you were, who was there, and what was happening. If you need some guidance here around possible feelings, a list of “true feelings” is provided in the second column of the table in Appendix B. Take your time to come up with how you truly felt during each of these difficult experiences, and one by one list these emotions in the third column (labeled True Feelings) of the table in Appendix A. [4] PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit Step 3: Identify your needs You can think of your feelings as “data.” Your feelings tell you that something you need is missing at this moment. For example, if you feel scared, this feeling tells you that there is a need for safety. Alternatively, if you feel overwhelmed, this feeling may tell you that you need to rest. Thus, your feelings inform you about something that you need at that moment. Now that you have an understanding of how you truly felt (i.e., your emotion/s) at the time of each of your difficult past experiences, what do you think you might have needed at that time? For each feeling, take your time to consider your underlying, unmet need(s). If you need some guidance here about possible feelings, a list of possible underlying needs is provided in the third column (underlying needs) of the table in Appendix B. Step 4: Applying what you have learned Now that you have learned how to distinguish your true emotions and underlying needs from a faux feeling, you can begin to use this skill in your everyday life. Why is it important to be able to name your true feelings and avoid using faux feelings? First, when you can describe your feelings (i.e., “I feel angry”) rather than the believed cause of your feelings (i.e., “I feel attacked”), you take full responsibility for your feelings. No matter who or what triggered a feeling, it is still your feeling. It is you who experienced it in this particular way. Another person in the very same situation may not experience that feeling. Feelings are personal, and by acknowledging that a feeling is “yours,” you have a powerful tool at your disposal: you can now let others know how you feel without offending them. Just picture yourself telling the other person, “I feel attacked.” Automatically, this statement puts the other person in the role of the perpetrator, the person who is “wrong.” Indirectly you are saying, “You did this to me, you attacked me!”. The other person is likely to feel offended and may experience a strong need to defend him/herself, especially when he/she never intended to attack you. He/she may call your response “nonsense” and try to convince you that he/she did not attack you. In turn, you feel as if he/she is not taking your supposed feelings seriously and try to make him/her understand why he/she did attack you. As you notice, this can take a long time and may get from bad to worse. Perhaps the biggest problem with faux feelings is that they cause you to believe that the solution is to be found outside yourself. You believe that if the other person changes his/her behavior, your feeling will go away, or when the other person apologizes, then you will be fine. When we expect other people’s reactions to solve our painful feelings, we give away our autonomy. We become dependent on whether they behave in the way we want or expect them to. This is very tricky, as others often do not behave this way. The next time you find yourself basing your feelings on the actions of another person, check-in on whether this feeling is a ‘faux’ feeling and whether you are experiencing another emotion, deeper down. Allow yourself to open up to your inner world and observe and connect with your true feelings and needs. If you decide to talk about your feelings with the person(s) who triggered these feelings, try to talk about your feelings and your needs. Remember, the other person may deny your faux feeling (i.e., “I never attacked you”), but he/she may never deny your true feelings. If you express that you feel anger, it would be very strange for the other person to deny this and say, “no, you do not!” [5] PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit Appendix A: Faux Feelings Table Faux Feeling Past Experience True Feeling(s) Underlying Need(s) E.g., Betrayed E.g., A friend relayed a secret of mine to others. E.g., Hurt, Angry, Disappointed, Anxious E.g., Trust, Loyalty, Reliability, Commitment Attacked Criticized Disrespected Intimidated Misunderstood Rejected Taken advantage of Unsupported Violated [6] PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit Appendix B: Examples of true feelings and possible needs underlying faux feelings Faux Feelings (Causal attributions) True Feelings Underlying Needs Attacked Scared, Angry Safety, Respect Belittled Indignant, Distressed, Tense, Embarrassed, Outraged Respect, Autonomy, To Be Seen, Acknowledgment, Appreciation Blamed Angry, Scared, Antagonistic, Bewildered, Hurt Fairness, Justice, Understanding Betrayed Stunned, Outraged, Hurt, Disappointed Trust, Dependability, Honesty, Commitment, Clarity Boxed In Frustrated, Scared, Anxious Autonomy, Choice, Freedom, Self-Efficacy Coerced Angry, Frustrated, Scared, Anxious, Autonomy, Choice, Freedom, Self-Efficacy Criticized Humiliated, Irritated, Scared, Anxious, Embarrassed Understanding, Acknowledgment, Recognition Disrespected Furious, Hurt, Embarrassed, Frustrated Respect, Trust, Acknowledgment Distrusted Hurt, Sad, Frustrated Honesty, Authenticity, Integrity, Trust Harassed Angry, Aggravated, Pressured, Frightened, Exasperated Respect, Consideration, Ease Hassled Irritated, Irked, Distressed, Frustrated Autonomy, Ease, Calm, Space Insulted Angry, Embarrassed, Incensed Respect, Consideration, Acknowledgment, Recognition Interrupted Irritated, Hurt, Resentful Respect, Consideration, To Be Heard Intimidated Frightened, Scared, Vulnerable Safety, Power, Self-Efficacy, Independence Left Out Sad, Lonely, Anxious Belonging, Community, Connection, To Be Seen Manipulated Resentful, Vulnerable, Sad, Angry Autonomy, Consideration, Choice, Power [7] PositivePsychology.com | Positive Psychology Toolkit Faux Feelings (Causal attributions) True Feelings Underlying Needs Misunderstood Upset, Dismayed, Frustrated Understanding, To Be Heard, Clarity Pressured Overwhelmed, Anxious, Resentful Relaxation, Ease, Clarity, Space, Consideration Rejected Hurt, Scared, Angry, Defiant Belonging, Connection, Acknowledgment Taken Advantage of Angry, Powerless, Frustrated Autonomy, Power, Trust, Choice, Connection, Acknowledgment Taken for Granted Hurt, Disappointed, Angry Appreciation, Acknowledgment, Recognition, Consideration Tricked Indignant, Embarrassed, Furious Integrity, Honesty, Trust Unappreciated Sad, Hurt, Frustrated, Irritated Appreciation, Respect, Acknowledgment Unsupported Sad, Hurt, Resentful Support, Understanding Violated Outraged, Agitated, Anxious, Sad Safety, Trust, Space, Respect [8]