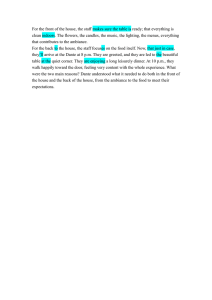

The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 brill.com/ywml Duecento and Trecento (Dante) Anthony Nussmeier University of Dallas 1 General The year 2020 represents the build-up to a year filled with celebrations of Dante as Italy and the world prepare to commemorate the 700th anniversary of the great poet’s death. The approach of the necroversary has, not unexpectedly, stimulated interest in the life of Dante, and as a result a flurry of biographies has been published in 2020. Just to name a few, there is John Took’s massive Dante (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 608 pp., complemented by Alessandro Barbero’s historical Dante (Rome: Carocci, 2020), 361 pp. in Italian; Alberto Casadei’s Dante e le guerre: tra biografia e letteratura (Ravenna: Longo, 2020), 196 pp.; Aldo Cazzullo’s A riveder le stelle. Dante, il poeta che inventò l’Italia (Milan: Mondadori, 2020), 288 pp.; and Guy Raffa’s Dante’s Bones: How a Poet Invented Italy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 384 pp. (This last is more a biography of Dante’s remains, but it still counts, and it shares a subtitle with the work by Cazzullo.) There are also numerous new works that lie somewhere between biography and reception: Giovanni Caserta’s Dante settecento anni dopo, 1321–2021 (Calvello: Villani Editore, 2020), 268 pp.; Casadei’s Dante. Storia avventurosa della Divina commedia dalla selva oscura alla realtà aumenta (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 2020), 200 pp.; Took’s Why Dante Matters, Stefania Meniconi’s Dante Alighieri, giovane tra i giovani (Verona: Gingko Edizioni, 2020), 180 pp.; and a collective handbook on all things Dante edited by Roberto Rea and Justin Steinberg, entitled, creatively, Dante (Rome: Carocci, 2020), 409 pp. There are also multiple works that study Dante’s Epistles, and these can be said to advance an interest in understanding Dante the (political) man: Benoît Grévin’s Al di là delle fonti ‘classiche’. Le Epistole dantesche e la prassi duecentesca dell’ars dictaminis (Venice: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, 2020), 178 pp., Casadei’s Nuove inchieste sull’epistola a Cangrande. Atti della giornata di studi (Pisa, 18 dicembre 2018) (Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2020), 234 pp., and Le lettere di Dante. Ambienti culturali, contesti storici e circolazione dei saperi, ed. by Antonio Montefusco and Giuliano Milani (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), 626 pp. (This volume, is, according to Montefusco’s introduc- © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2022 | doi:10.1163/22224297-08201009 236 romance languages · italian studies tion, evidence of the recent biographical turn in Dante Studies.) In addition to the studies on Dante’s Letters, there is also a trio of books that treat Dante ‘minore’ and the Vita nova either exclusively or comprehensively: Vincenzo Crupi and Andrea F. Calabrese, La Trinità in Dante dalla ‘Vita Nuova’ alla ‘Divina Commedia’ (Rome: Rubbettino, 2020), 140 pp., and two by Stefano Carrai, Dante elegiaco. Una chiave di lettura per la Vita nova (Florence: Olschki, 2020) 122 pp., and Il primo libro di Dante. Un’idea della Vita nova (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2020), 141 pp. Finally, there is a renewed interest in Dante and satire as represented by a pair of volumes, Nicolino Applauso, Dante’s Comedy and the Ethics of Invective in Medieval Italy. Humor and Evil (Lanham: Lexington, 2020), 350 pp., and Dante Satiro: Satire in Dante Alighieri’s Comedy and Other Works, ed. by Fabian Alfie and Nicolino Applauso (Lanham: Lexington, 2020), 230 pp. 2 Comedy Simone Bregni, Locus amœnus. Nuovi strumenti di analisi della Commedia (Ravenna: Longo, 2020), 250 pp., argues in favour of intertextuality, especially when applied to premodern texts such as the Comedy. ‘Intertextuality’, the author declares, ‘is not dead’ (p. 9). On the contrary, because of the different relationships that existed between texts in the medieval period, as well as the diverse methods of cultural transmission, intertextuality becomes an important instrument of analysis. In this vein, Bregni follows Cesare Segre, Maria Corti, and Christopher Kleinhenz in arguing for the relevance of such an approach due to the complexity of interactions that characterized medieval and Renaissance cultural production. As such, he aims to focus on a specific topos (locus amœnus) as a case-study for a revivified intertextual approach to studying Dante and the Comedy. This renewed focus will consider how intertextuality in the medieval period ‘trascende i limiti imposti dalla citazione diretta perché il riferimento ad altri testi [era] sempre in un contesto di translatio/imitatio/æmulatio’ (p. 11). Helpfully, Bregni also calls attention to the role of memory in medieval cultural production and the mental libraries that would have alerted many medieval readers to the vast number of implicit, though still recoverable, allusions to classical and biblical texts. Given the constancy of the presence of the locus amœnus in classical and medieval literature, and its importance in Dante, Bregni believes that a study of its intertextuality will illustrate his methodology. (Though he prefers the term ‘intertextual imitatio’ to intertextuality.) The site of the locus amœnus becomes fruitful for studying medieval imitatio and literary one-upmanship, exemplified by the Elysian Fields present in Homer, Virgil, Ovid, and many other Latin and Greek authors, The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 237 not to mention the similarities with the Bible’s Garden of Eden as well as with similar manifestations in every major world religion. After an initial chapter on intertextuality and medieval literature, Bregni explores diverse loci amœni. First, in Chapter 2, the ‘imperfect’ Edens of Inferno 4 and Purgatory 7. Second, in Chapter 3, earthly paradise and Purgatory 22–23 and 28–33, followed by forays into Purgatory 29 and Purgatory 30–33. Finally, in Chapter 6, Bregni examines Paradise, with an emphasis on Paradise 1–3 and Paradise 23, 26, 30, and 33. In order to demonstrate how Bregni’s reimagined intertextuality, or intertextual imitatio, works in regard to the traditional topos of the locus amœnus and the Comedy, let’s consider Chapter 2, ‘Paradisus terrestris—Loci amœni imperfetti: Inferno iv e Purgatorio vii’. Bregni begins by noting Dante’s distinction between ‘earthly paradise’ (Eden, for example) and ‘celestial paradise’, and avers that the imperfect loci amœni of Inferno and Purgatory possess an evident intertextuality with pagan classical texts, while the relationship to texts from the Christian tradition is much less apparent (p. 48). According to Bregni, Dante’s deliberate use of pagan texts to represent these earlier ‘imperfect’ Edens is meant to prepare the reader: ‘svolgono il ruolo di accrescere il coinvolgimento empatico del lettore, spingendolo a aspirare e anelare maggiormente alla meta a cui l’intero poema prepara e rimanda: l’unione perfetta e completa delle anime beate a Dio’ (p. 49). Thus, even the use of existing texts would reflect the trajectory of the poem, a trajectory that manifests itself in music, language, and imitatio. The very first verses of the Inferno, then, with the selva traditionally associated with the locus amœnus, allude to the earthly unhappiness stemming from original sin and the Garden of Eden. As it regards Inferno 4, Bregni believes that the place ‘apart’ created by Dante—Limbo—contains many allusions to classical literature and the topos of the locus amœnus, references the Elysian Fields, the insulae fortunatae, and other pagan paradises. However, he adds, ‘Dante distanzia [the locus amœnus] chiaramente sia dall’Eden, sia dal paradiso escatologico’ (p. 51). The author enumerates some of the characteristics of Limbo and its differences with respect to the Book of Genesis (no city, one river instead of four, and so on). But what are the referents, and how does Dante choose them? At first glance the intertextual allusions are pagan, but Bregni proposes that the single river of Limbo is a clear reference, at least in the mind of Dante’s medieval readership, to Apocalypse 21–22, as well as to Exodus 14 and 22. Thus, for Bregni, ‘il fiume sarebbe da interpretare come figura Christi’ (p. 52). The pagan intertextual sources, which constitute ‘l’immagine di un falso, imperfetto paradiso’ are more readily apparent, while the biblical referent, less apparent, ‘richiede l’intervento ermeneutico del lettore per essere riconosciuta’ (p. 53). As a result, the author concludes, ‘Dante si stia servendo di intertestualità classica per delineare un locus amœnus, ma di intertestualità biblica per The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 238 romance languages · italian studies rivelare il limite di tali paradisi, in sé imperfetti’ (p. 58). Bregni’s approach to intertextuality encourages us to think about the cultural preparation and knowledge of Dante’s medieval readers. Jason Baxter, The Infinite Beauty of the World. Dante’s Encyclopedia and the Names of God (Berlin: Peter Lang, 2020), 180 pp. is an erudite study that takes as its point of departure Dante’s legendary encyclopedism. Contrasting Dante’s approach with what Virgil, by way of ‘folding’ was only presumed to have done, the author catalogues, in the introduction, Dante’s voluminous, in-text presentation of a visual mappa mundi. Baxter describes Dante’s encyclopedism thus: ‘the poet intentionally gathered creatures, places, landscapes, and practices from across the world and types of encyclopedic texts and then filled his book with their imagines; and, second, the poet consistently and insistently constructs moments in which we—along with the pilgrim— must take it all in at a glance, as if we are viewing the whole imago mundi from above’ (p. 15). Baxter’s intertextual approach has much to recommend it, and much in common with Simone Bregni’s understanding of intertextuality in Locus amœnus. Nuovi strumenti di anlisi della Commedia. For example, in Chapter 3 the author highlights the specific textual allusions to which Dante makes reference in Hell—the encyclopedic imago mundi—to lay bare the ‘limitations’ of characters such as Brunetto Latini, Francesca da Rimini, Pier della Vigna, and Ulysses. Relatedly, Chapter 4’s focus on Purgatorio 28 and the topos of the paradiso terrestre also covers the same territory as Bregni’s study. Baxter’s fifth chapter and conclusion consider the final canticle of the poem and examine its metaphoricity, as well as the extraordinary way in which Dante’s ‘kaleidoscopic’ encyclopedism manages to ‘create the miracle of unity in multiplicity’ (p. 132). The author acknowledges the limitations of his proposals for possible Dantean sources, but nevertheless pursues them in an attempt to ‘open up new and fruitful lines of interpretation of Paradiso’ (p. 132). Laura Pasquini, “Pigliare occhi per aver la mente”. Dante, la Commedia e le arti figurative (Rome: Carocci, 2020), 281 pp. explores the relationship between Dante’s experience with the figurative arts and all three canticles of the Comedy: ‘Patire l’Inferno’, ‘Sentire il purgatorio’, and ‘Figurare paradiso’. As the title indicates, Pasquini departs from Gregory the Great’s exhortation (Paradise 27.92) and relates it to an epistle written by the same Gregory in which he ‘ammoniva il presule [the Bishop of Marseilles] per aver rimosso le immagini dalle chiese della sua diocesi’ (p. 9). Building on the work of Frances Yates on memory in general and of Lucia Battaglia Ricci on Dante in particular, Pasquini reminds us that ‘Dante visse in un contesto culturale in cui molto del messaggio politico e religioso era affidato al mondo delle immagini’ (p. 10). As with Dante’s intellectual, book-based library, hypotheses regarding conceptual-visual influences on Dante are fraught with hazard, as it is almost impossible to say with certainty The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 239 that Dante had the opportunity, or the desire, to see certain images (pp. 12–13). Nevertheless, we must, writes Pasquini, accept Dante’s testimony about having seen various works of art. How does Dante use the figurative arts? Pasquini sums it up neatly toward the end of the book: ‘immagini, formule testuali o figurate, mai ricalcate o richiamate direttamente, che filtrano in maniera più o meno consapevole dalla memoria e vanno a costituire l’impalcatura della visione che la poesia sublima’ (p. 216). In other words, Pasquini’s methodology resembles a figurative arts version of Bregni’s ‘intertextual imitatio’. In the monograph’s first section—like the other two, enriched by a dense apparatus of coloured photographs of the frescos, paintings, churches, buildings, and sculptures being considered—Pasquini explores the relationship between Inferno and the figurative arts, first in Inferno 21 and the ‘inferno di Torcello’, and then the vultus trifrons of Lucifer (Inferno 34.38: ‘vidi tre facce a la sua testa’). Her first case-study of the Inferno is focused on Venice, whose shipbuilding yard is described with such great attention in Inferno 21. Pasquini remarks on the similarity between the swampy Torcello Island and diverse descriptions of the Inferno. On Torcello there is—and there was when Dante could have encountered it in 1321 or earlier between 1304–1306 when, though there is no documentary evidence, he was likely in nearby Treviso—the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta. Inside of the church is an extraordinary fresco. There is the Anastasis, and, as Pasquini observes, ‘l’evento descritto da Dante nel canto iv dell’Inferno (vv. 52–63) risponde in arte a un’iconografia estremamente diffusa nel Medioevo’ (p. 25). There is, though, another detail of Santa Maria Assunta’s depiction of the Anastasis that connects it more directly to Dante and the geography of his Inferno: a possible representation of Limbo and of its unbaptized children, the limbus puerorum. Another precise detail of Torcello that has an analogue in the Comedy is Inferno 7 (pp. 31–32). Even the river Styx and the lake Cocito are attested to in Torcello, unique on Italian soil for their visual representation (p. 34). In her methodology, Pasquini observes those examples of the three-faced head representing the Trinity that Dante could have seen: they include the volti trifronti in the cloisters of St Paul Outside the Walls in Rome and the Church of St. Peter in Tuscania, later Toscanella (p. 39), as well as the Archbishop’s palace in Treviso. In Purgatorio, argues Pasquini, Dante ‘mette palesemente a frutto la propria sensibilità artistica, esternando evidenti competenze e una naturale familiarità nei confronti della cultura figurative del suo tempo’ (p. 79). In contrast to artistic representations of Heaven and Hell, which had been occurring for centuries, the creation of a third place with a specific name and precise attributes only dates back to less than one hundred years before Dante’s birth (p. 80). But already from the ninth century on there were visual depictions of the process of purgation and purification, even The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 240 romance languages · italian studies without the name Purgatory. Pasquini’s treatment of Purgatory begins in the likely canto: Purgatory 10 and its focus on art, specifically the three bas-reliefs drawn from the Old and New Testaments and from ancient Roman history: the Annunciation, David and the Ark of the Covenant, and Trajan and the widow (p. 90). Following Picone and Emilio Pasquini, Pasquini notes that the directly divine nature of the art on that first terrace is Purgatory 10. It is not mimesis of nature, but is on a plane that is higher still: divine. Dante elevates poetry because only it can capture that art (p. 92). Still, in the second canticle Dante could have taken direct inspiration from the art around him. Again, in Purgatory 10, Dante compares the proud spirits to the telamoni, sculptures he would have seen first-hand in Bologna at St. Stephen, the duomos of Modena and Verona, and his own precious Baptistry of St. John in Florence, to name only a few. One of the most important aspects of Pasquini’s study of the figurative arts and Purgatory concerns Dante’s evocation of Cimabue and Giotto in Purgatory 11.94–99, and whether he would have seen their artistic works in person. Pasquini cites Elvio Lunghi and his authoritative statement that ‘vivente Dante, dipinti di Cimabue e di Giotto erano visibili anche a Firenze, Pisa e Roma’ (p. 113), but adds that ‘questa terzina [Purgatory 11. vv. 94–96] potrebbe essere state concepita proprio all’interno di quella chiesa [la basilica superiore di San Francesco ad Assisi].’ Pasquini agree with Lunghi and Antonio Paolucci that Giotto was already renowned at the time of the writing of Purgatory, and that ‘il poeta aveva anche potuto toccare con mano la grandezza di quell’arte’ (p. 115). In the third and final section of the book, Pasquini undertakes a study of the relationship between Paradise and the figurative art of Dante’s time. She begins by asserting that the ‘veicolo primario’ for Dante’s imagining paradise ‘era il mosaico, apprezzato dal poeta ancora prima che come vettore di specifiche iconografie, come tecnica dotata di una particolare materialità e di un’estrema, unica, lucentezza’ (p. 127). In other words, as she has done for the first two canticles, Pasquini argues that different media of the figurative arts lend themselves to each of the three canticles, a sort of specificity in the visual intertextuality. In this chapter, Pasquini proposes that Purgatory 28 onward be read as a sort of ‘preamble’, or Ante-Paradise, and she seeks to find artistic sources of inspiration for Dante’s depiction of the locus amoenus, of Earthly paradise. She proposes, as works of art that Dante could have seen based on what we know for certain of his movements, St. John in Porta Latina, the Abbey of St. Peter in Ferentillo, the Church of St. Paul inter vineas in Spoleto, and St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. Pasquini concludes her study with a reflection on the canticle-ending ‘stelle’ and their role in the figurative arts. Among the sites that could have inspired Dante are the Chapel of Sts. Primus and Felician in the Basilica of St. Stephen in the Round, the Basilica of St. Agnes, The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 241 St. Mary Major, and certainly Ravenna and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia and the Basilica of St. Apollinaire. Dante, ed. by Roberto Rea and Justin Steinberg (Rome: Carocci, 2020), 409 pp., is an Italian-language handbook that is a sort of Oxford Companion to Dante in Italian. It features eighteen chapters divided into ‘Opere’ and ‘Questioni’. Particularly helpful is the updated ‘Bibliografia’ (pp. 363–392). The first section, ‘Opere’, includes ten accessible essays on Dante’s works—both acknowledged and only attributed, included the most controversial, the Fiore—in what is more or less chronological order: Rime, Vita nova, Convivio, De vulgari eloquentia, Commedia, Monarchia, Epistole, Egloghe, Questio de aqua et terra, Fiore (e il Detto d’amore). Part Two, ‘Questioni’, features eight essays on important topics and themes in Dante’s corpus, many of which complement other volumes reviewed here: Elisa Brilli, ‘Dante, Firenze e l’esilio’ (pp. 199–218); Enrico Fenzi, ‘Dante politico’ (pp. 219–244); Giovanna Frosini, ‘Il volgare di Dante’ (pp. 245–266); Paola Nasti, ‘Dante e la tradizione scritturale’ (pp. 267–286); Ronald L. Martinez, ‘Dante e la tradizione liturgica’ (pp. 287– 306); Pasquale Porro, ‘Dante e la tradizione filosofica’ (pp. 307–328); Stefano Carrai, ‘Dante e la tradizione classica’ (pp. 329–344); and Lino Leonardi, ‘Dante e la tradizione lirica’ (pp. 345–362). With respect to books reviewed here, Elisa Brilli, ‘Dante, Firenze e l’esilio’ (pp. 199–218), summarizes Dante’s relationship to his city of birth and can accompany the numerous biographies of the poet published in 2020. The essay by Stefano Carrai, ‘Dante e la tradizione classica’ (pp. 329–344), can be read together with Simone Bregni’s Locus amœnus. Nuovi strumenti di analisi della Commedia. Paola Nasti, ‘Dante e la tradizione scritturale’ (pp. 267–286), and Ronald L. Martinez, ‘Dante e la tradizione liturgica’ (pp. 287–306), complement George Corbett’s Dante’s Christian Ethics. Purgatory and Its Moral Contexts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 246 pp. which is an elegant study of the second canticle of Dante’s Commedia. Corbett’s study has much in common with two other volumes reviewed here— Dante’s Comedy and the Ethics of Invective in Medieval Italy. Humor and Evil and Dante Satiro. Satire in Dante Alighieri’s Comedy and Other Works—in its desire to reorient our reading of Dante to its ethical component along the lines recommended by Dante, or at least those of an early glossator of his poem, in the Letter to Cangrande. It also represents a continuation of the theologically focused publications from 2018 (Maldina, and others) due to Corbett’s focus on penitential sources and an emphasis on the ‘popular’ nature of the Commedia and its sources, paying attention to Dante’s intellectual formation separate from ‘bookish high Aristotelian philosophy’ (p. 5). (Here Corbett also contributes to recent work by Zygmunt Barański and others on Dante’s intellectual formation.) The book can also be read profitably with three works from 2019, all of which discuss Purgatory: Gennaro Sasso, Purgatorio e Antipurgatorio. The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 242 romance languages · italian studies Un’indagine dantesca (Rome: Viella, 2019); Purgatorio, ed. Saverio Bellomo and Stefano Carrai (Torino: Einaudi, 2019); and Alessandro Vettori, Dante’s Prayerful Pilgrimage. Typologies of Prayer in the ‘Comedy’ (Leiden: Brill, 2019). In Chapter 1, Corbett proposes that we ought to recognize different organizing ethical principles for the Inferno, Purgatory, and Paradise. In Chapter 2, Corbett argues that the political dimension of the Comedy complements, rather than advances, Dante’s theories in the Monarchia. Chapters 3 through 7 focus on Purgatory. Most significantly, Corbett aims to reorient our understanding of Dante’s approach away from Aquinas and towards William Peraldus, another Dominican. In Chapter 4, for example, one of two chapters making up Part Two (‘Reframing Dante’s Christian Ethics’), Corbett makes the case for a comparative analysis of Peraldus’s De vitiis et virtutibus and the second and third canticles of the Comedy. According to the author, the difference between Aquinas and Peraldus is highly significant because they ‘adopted very different approaches in their treatment of vices and virtues’ (p. 86). How did they differ? Most notably, Peraldus proposes a bipartite structure: a journey from vice with specular virtue and a journey to heaven. Sound familiar? Corbett reminds us that Peraldus’s work was so influential that ‘a decree required that every Dominican convent hold a copy of Peraldus’s Summa de vitiis et virtutibus’, and that ‘the second part of Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae would only supersede Peraldus’s treatise as the Dominican handbook for moral theology and pastoral care in the late fourteenth century’ (pp. 89–90). Given the structural similarities—‘the seven vices (with their corresponding remedial virtues, gifts of the Holy Spirit, and beatitudes) structure Peraldus’s De vitiis and the seven terraces of Dante’s Purgatory; the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues structure Peraldus’s De virtutibus and Dante’s Paradise’ (p. 101)—Corbett’s insights provide ample evidence to reconsider the influence of Peraldus on Dante. Alberto Casadei, Dante e le guerre: tra biografia e letteratura (Ravenna: Longo, 2020), 196 pp. is the latest edition of the Letture classensi, and as Maurizio Tarantino writes in the Preface, ‘la scelta di tema’ was not casual, coinciding with the centenary of the end of World War i. The overarching theme of the volume—Dante and war—is subdivided into ‘La guerra nella vita e nelle opere di Dante’ and ‘Dante nella rappresentazione delle guerre contemporanee’, with a coda composed of two brief contributions: Luca Azzetta, ‘Dante alle soglie dell’eterno: visioni bibliche e poesia tra l’Epistola a Cangrande e la Commedia’, and Lucia Battaglia Ricci, ‘La Commedia nello specchio delle immagini’. The first section is comprised of three essays: Alberto Casadei, ‘Dante, la guerra e la pace nel poema sacro’ (pp. 11–26); Diego Quaglioni, ‘Fra teologia e diritto. Pace e guerra giusta nella Monarchia’ (pp. 27–44); and Alessandro Barbero, ‘Dante a Campaldino, fra vecchi e nuovi fraintendimenti’ (pp. 45–60). Part Two contains three reflecThe Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 243 tions on the use and reception of Dante in the literature on war in the twentieth century. Martina Mengoni, ‘Dante, Primo Levi, Auschwitz’ (pp. 61–78); Paola Scrolavezza, ‘Dall’orrore del reale all’incubo della distopia: gli inferni di Dante in Giappone tra romanzi e manga’ (pp. 79–92); and Helena Janeczek, ‘Dante: le sue parole e le nostre guerre’ (pp. 93–102). In the interest of space, I will consider at length one essay. Perhaps most interesting from the 2019 cycle is Martina Mengoni’s reflection on Dante and Primo Levi, which has three objectives: the delineation of the status quaestionis of the ‘canto di Ulisse’ in Se questo è uomo; the moral universe of Levi’s Se questo è uomo and Sommersi e i salvati; and the connection between the ineffability of absolute evil in Levi and Dante’s ‘trasumanar significa per verba non si poria’ of Paradise vv. 70–71. Mengoni begins with George Steiner’s observation about Auschwitz and Inferno 33.94–96, namely that, even if one hasn’t been to Auschwitz, it is enough to read Dante: ‘Lo pianto stesso lì pianger non lascia, / e ’l duol che truova in su li occhi rintoppo, si volge in entro a far crescer l’ambascia’. If, on the other hand, there is something unsayable about Auschwitz, there is nevertheless ‘una guida all’Inferno già pronta e già scritta, quella di Dante’ (p. 63). Mengoni calls our attention to ongoing research by Riccucci, wherein she identifies references to Dante in non-literary texts—narratives, interviews, diaries, letters—of Holocaust survivors. Suffice it to say, the Comedy in general, and Inferno in particular, is a common touchstone. If there are two poles—to read Dante is to understand Auschwitz and there is no way to understand Auschwitz— where is Levi (p. 64)? For Mengoni we must first interrogate Chapter 10 of Se questo and its use of Inferno 26, the chapter in which Primo Levi teaches Pikolo Italian using the canto of Ulysses (p. 65). According to Mengoni, there are three ‘macro-categories’ of interpretations (pp. 66–70). These categories include: (1) the canto di Ulisse as a commentary on language and on the Babelic nature of the lager in relation to the clarity of language itself; (2) an example of ‘suspended time’; (3) and a chapter of the ‘saved’: Pikolo and Primo Levi, Dante and Ulisse. It is clear that Mengoni adheres to the Steinerian interpretation of Primo Levi and Auschwitz, that is, that through Dante it is possible to have a guide to the Hell that is the concentration camp. Following the exposition of the three interpretations of the canto di Ulisse, Mengoni alights on the way in which Levi creates figurae on the basis of the Comedy. First, the soldier who greets prisoners on the train-car as a sort of ‘anti-Caronte’ and representative of an Arendtian banality of evil. Second, Doktor Pannwitz, who ‘siede formidabilmente’, as a sort of concentration camp version of Minos (‘stavvi Minòs orribilmente’), in whose hands lay the fate of Primo Levi; and, finally, in Sommersi e i salvati, Levi ‘non pesca dall’inferno dantesco ma costruisce il personaggio che piu di tutti rispecchia il senso delle figure dantesche come preferigurazioni’ (p. 74): MordeThe Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 244 romance languages · italian studies chai Chaim Rumkowski. The final section of this essay compares the contextual ineffability of Paradise and Se questo. In the end, concludes Mengoni, ‘è chiaro che Levi non trovo solo in Dante gli strumenti per raccontare il dolore e il terrore di Auschwitz […] Riuscì a forgiare una sua lingua che conteneva questi autori [Dante, Conrad, Mann] ma li rimsemantizzava’ (p. 77). Stefania Meniconi, Dante Alighieri, giovane tra i giovani. Cinque studi sulla vitalità di Dante (Verona: Gingko Edizioni, 2020), 180 pp. is a breezy volume consisting of vignettes meant to illustrate ‘Dante popolare’, that is, that ‘Dante è vivo. Ci parla’. An initiative of the Società Dante Alighieri di Verona, Meniconi’s collection of essays is divided into five sections. The first, ‘Il sistema linguistico dantesco: efficacia e persistenza’, features five mini-essays on words and the sounds of the Comedy. Meniconi’s insights straddle the popular and the scholarly, and communicate Dante’s ingenuity in an engaging manner; for example, in ‘Suoni che graffiano’, Meniconi studies the phonics of the poem, noting the use of the muta + r to inculcate in the shades of Inferno 3 a fear of Charon: ‘Ci dimostra che l’efficacia comunicativa della poesia dantesca risiede non solo nella scelta (e talora nell’invenzione) di parole immorali, ma anche nella sapiente sequenza fonica con cui vocali e consonanti si dispongono nel verso’ (p. 26). In Purgatory 1, on the other hand, Dante makes use of liquid consonants such as ‘l’ and ‘r’ that reflect the aqueous content of the purgatorial canticle. In ‘Il sistema linguistico dantesco: riciclaggio contemporanei’, Meniconi explores the role of Dante’s language in our contemporary lives, from those verses that have become proverbial, to twentieth-century poetry, to popular music. Usefully, she reminds us in ‘Le parole delle canzoni’, that many contemporary popular artists have used Dante as inspiration. The progressive rock band Metamorfosi even dedicated three entire albums to him, published in 1972, 2004, and 2014 as Inferno, Paradise, and Purgatory, respectively (p. 53). It goes without saying that, as with the English Romantics in the nineteenth century, the most-cited canto is Inferno 5, with artists from Antonello Venditti and Jovanotti to De André making reference to Paolo and Francesca. The third section of Dante Alighieri, giovane tra i giovani centers on ‘Questioni di sopravvivenza’ and recounts, essentially, how Dante can save your life. (This section can be read together with the ciclo di lezioni of the Letture classensi.) The obvious reference is to Primo Levi’s Se questo è uomo, for which, writes Meniconi, Levi recognizes in Dante ‘una potenza che è in grado, per la prima volta dopo giorni e mesi, di farlo sentire ancora—e nuovamente—uomo’ (p. 66). But Meniconi notes other experiences of ‘salvation through Dante’ as disparate as Albanian Catholic dissident Pashko Gjeçi under Hoxha and Osip Mandel’štam during the reign of Stalin. In section four, ‘Dante psicologo della classe’, Meniconi turns her attention to the teaching of Dante. Particularly delightful is the assignment she gives The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 245 her student to ‘adopt’ a favourite terzina. Topics such as l’amore—and obviously Inferno 5—as well as l’amicizia prevail, but at times, students choose unexpected passages and their reflections on them reveal the great humanity contained in the poem. For example, a student named Giuseppe chose the moment in Purgatory 30 when Dante announces the departure of Virgil, and writes that ‘[fa] sparire i secoli che ci separano. Un figlio che confida al padre i suoi sentimenti, ma che è costretto ad affrontare da solo il lungo cammino che lo aspetta’ (p. 97). The fifth and final section, ‘Il mondo di Dante’, groups together ten mini-essays on various themes ranging from ‘amore e amicizia’ and ‘Italia’ to ‘povertà’ and ‘libro’. Nicolino Applauso, Dante’s ‘Comedy’ and the Ethics of Invective in Medieval Italy (Lanham: Lexington, 2020), 350 pp. investigates the role of invective and satire in Dante’s epic poem, and complements the volume Dante Satiro. Satire in Dante Alighieri’s ‘Comedy’ and Other Works (reviewed below). Applauso takes a more global approach to the study of invective in medieval Italy. Sandwiched between the opening introductory chapters and a discussion of praise and blame in Dante (Chatper 6: ‘Humor and Evil in Dante’s Global Invective’), Applauso presents three chapters on some of Dante predecessors and contemporaries and their use of invective (Rustico Filippi, Cecco Angiolieri, and Folgore da San Gimignano). In Chapter 1, ‘The Invective Genre in Dante and His Contemporaries’, he outlines his new approach to the study of invective in medieval Italy. Applauso aims to ‘emphasize the ethical project of medieval political invective, [and to argue] that these comic texts are rooted in and actively engaged with the social, political, and religious conflicts of their time’ (p. 2). He considers theories of humour, laughter, and the comic before giving a definition of invective: ‘the practice of verbally insulting, attacking, and ridiculing an opponent either orally or in writing’ (p. 10). After a brief examination of classical precursors, Applauso turns to the question of invective in both Latin and the vernacular in the European Middle Ages. He then provides a status questionis with regard to critical approaches to studying invective in the Italian context, with a particular emphasis on Mario Marti and his subsequent critics. Of interest here is Chapter 6 and Applauso’s study of Inferno 19, Purgatory 6, and Paradise 27, three canti, one from each of the Comedy’s three canticles, distinguished by the presence of unrestrained invective on the part of Dante the character and/or Dante the poet. According to Applauso, Dante is set apart from fellow practitioners of invective (like Filippi, Angiolieri, and da San Gimignano) because he ‘directs his invectives not merely toward single individuals, parties, or groups, but to entire political institutions and their leaders’ all over the Italian peninsula (p. 231). Dante’s penchant for invective has been clear from the beginning, since early readers of the poem used verbs such as ‘riprendere’, ‘condemnare’, and ‘mordere’ to The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 246 romance languages · italian studies describe Dante’s mode. Interestingly, Applauso singles out a young Alessandro Manzoni as one of the few to recognize the cohabitation of humour and blame in Dante, and cites the author’s lucid description of Dante: ‘Tu dell’ira maestro e del sorriso | Divo Alighier, le fosti’ (p. 243; emphases mine). In Chapter 6, Applauso begins with Inferno 19, which opens with invective in the very first verse: ‘the entire canto could also be conceived as an invective’ (p. 255). While the scholarship has recognized this, Applauso wishes to draw attention to the humour present especially in the dialogue between Dante the character and Pope Nicholas iii and in the second part of the invective in Inferno 19.88–93 and 112–114 (p. 261). In this infernal episode, as in Purgatory 6 and Paradise 27, the author concludes, through the use of invective, and indeed humour, ‘Dante seeks to provoke readers to act and thus not to remain mere passive observers’ (p. 265). Simone Marchesi and Roberto Abbiati, A proposito di Dante. Cento passi nella Commedia con disegni (Rovereto: Keller, 2020), 224 pp. is a delightful pastiche, a volume of mixed-media—text and drawings—that takes the reader from Inferno 1 all the way up to Paradise 33. Each of the one hundred mini-chapters features an exemplary terzina from each of the one hundred cantos, which, though they themselves are a sort of gloss, are accompanied by Marchesi’s learned, yet accessible, commentary. Roberto Abbiati’s illustrations are varied and always interesting, here abstract, there hyper-realistic. Among the favourites of this reviewer are ‘il dolce pedagogo’, the design that accompanies Purgatory 27, which depicts an adult Virgil leading a young Dante by the hand to his next guide, and the stark eye representing Inferno 11. Marchesi’s commentary highlights the humanity of Dante’s ‘poema sacro | al quale ha posto mano e cielo e terra’, as exemplified by what he writes apropos of Inferno 3, in a canto that is otherwise dark and foreboding at the entrance to the AnteInferno: ‘È una terzina che sorprende: una corrente di conforto amichevole passa attraverso un contatto fisico tra un personaggio d’ombra e uno vivente— due mani si toccano’. Or, better still, Inferno 15 and Dante’s celebrated encounter with Brunetto Latini. Here Marchesi comments, wearing his knowledge lightly, that in an encounter between student and teacher that is filled first with gestures, and only then with words, we find one of the most ‘unstable’ passages in the whole poem. Does Dante initiate a fraternal hug with Brunetto (‘e chinando la mia a la sua faccia’), or does he move his hand towards an (unfinished) caress (‘e chinando la mano a la sua faccia’)? One would like to be able to have Dante tell us, what, precisely, when one meets his maestro, ‘è il gesto in cui l’affetto si salda, una volta per tutte, al di là del tempo’? The volume, and indeed the commentary just cited on Inferno 15, possess a measure of poignancy given the Preface and its reproduction of an email exchange between the pupil Marchesi and his own maestro, the American Dantista Bob Hollander, who in the interim The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 247 between the publication of A proposito di Dante and this review, has gone up to the clouds from under which he wrote his final email (‘oggi sotto le nuvole’) to Marchesi. 3 Biography The upcoming anniversary year of 2021 is anticipated by a number of biographies of the poet. John Took, Dante (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 608 pp. is an exhaustive history of the cultural moment that gave rise to Dante in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Italy and a comprehensive biography of the poet himself. ‘Why do we have to know anything about Dante’s life? About Dante the man?’ So ventured, incautiously, we thought, a classmate of mine a decade or so ago in a graduate course on Dante. While the rest of the class sniggered—How could you be so daft? Of course, his life matters—my professor took the question as a serious one. Why indeed? For someone like Gabriele D’Annunzio, the turn-of-the-century decadent Italian poet, nothing in Dante’s biography mattered so much as ‘one single date [that] is to be solemnly considered and blessed, the day of the banishment: the twenty-seventh day of January of the year one-thousand three-hundred and two’. Writing in the introduction to the ‘monumental’ 1911 edition of the Commedia published by Leo Olschki and meant to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Italy’s founding (1861), D’Annunzio averred that, after the edict proclaiming Dante’s interdiction from Florence, ‘the poet enters into his real world and his real life, he readies himself to accomplish his heroic destiny under the auspices of Eternity’. Do we really need over 500 dense pages to understand Dante? Biographers of Dante, ever since Dante-admirer Giovanni Boccaccio’s medieval standard Vita di Dante in the 1360s, have been at pains to demonstrate just why, exactly, it is that Dante’s life matters so much to his literary output, especially since we know so little about the man whose ‘country was so ungrateful’. After all, as Giorgio Inglese put it in his 2015 biography Vita di Dante. Una biografia possibile, a ‘Cronologia minima’ composed of what we know for certain about Dante’s life by way of actual archival and manuscript evidence is exceptionally thin. Marco Santagata’s 2012 biography (published in English in 2016 as Dante: The Story of His Life) had already underscored the permeable nature of the boundary separating Dante the man from Dante the poet with the subtitle ‘il romanzo della sua vita’ (the novel, or story, of his life). On the one hand, to read a work of literature it is not necessary to know, for example, where or when the author was born, however crucial such details may be to understand the context of a literary work. Nevertheless, the biographical question concerning Dante is all the The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 248 romance languages · italian studies more pressing because Dante is the central character in his masterpiece and because, as the American Dantist Charles Singleton put it half a century ago, ‘the fiction of the Comedy is that it isn’t fiction’. Along comes John Took with a massive biography of the sommo poeta. In the first section of the book, which is given over to an exploration of the historical moment, Took mainly considers the paradox of Florence: despite all the political and social turmoil, the city was innovating politically during the 1270s and 1280s. The Buondelmonte episode and the internecine strife of the battles between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines are the backdrop: ‘Here, then, were Florence’s woes in a nutshell: the rise of any number of dominant and mutually antagonistic power blocs, partisanship in plenty, dynastic struggle, endless alignment and realignment, and a steady hovering on the brink of social and civic chaos’ (p. 3). Much of Took’s narrative in the first half is dependent on Giovanni Villani’s Cronica and Dino Compagni’s Nuova cronica, and in this respect his approach differs from that of Italian historian Alessandro Barbero, who in his Dante (Rome: Carocci, 2020), 361 pp. uses his fine knowledge of the archives and medieval documentary practice to illuminate Dante’s life and to augment whatever biographical information is conveyed second-hand or in Dante’s works. Barbero makes even a discussion of cognomi interesting. The second, third, and fourth sections of Took’s Dante, ‘The Early Years: from Dante da Maiano to the Vita nova’, ‘The Middle Years’, and ‘The Final Years’, approach Dante by way of his literary production. Took’s categorizations of ‘young’ Dante (Dante guittoniano, Dante cavalcantiano, Dante guinizzelliano) interpret Dante in light of traditional criticism and constitute a synthetic literary biography of Dante’s early corpus. Guy Raffa, Dante’s Bones. How a Poet Invented Italy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 384 pp. represents a unique entry in 2020’s biographies of Dante. Rather than a traditional biography, Raffa uses the unusual peregrinations of Dante’s earthly body after his death to recount the poet’s fortune in the centuries following his demise in 1321. In part this approach stems from the fascinating vicissitudes involving the poet’s bones—buried, moved, reburied and fought over between Ravenna and Florence for hundreds of years—while on the other hand it is also a clever way around a problem that has plagued biographers of Dante since Giovanni Boccaccio’s fourteenth-century biography Trattatello in laude di Dante: we simply do not know much about Dante’s life, at least in the way of documentary and archival evidence, and, as Dante biographer Giorgio Inglese noted back in 2015, the sum total of things we know for certain about Dante’s movements amounts to about two-and-a-half pages of bullet-pointed statements. As with all biographies, an author must take certain liberties, but there is a reason that biographies of the sommo poeta are subtitled ‘una vita possibile’ or ‘la storia di una vita’. Raffa’s contribution is no The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 249 exception. In addition to the obvious—he reminds us that all dialogue reported in Dante’s Bones is necessarily invented—he reiterates that we have nothing extant in Dante’s hand: not a single work of Dante’s survives today (pp. 13– 14). In three sections—‘Bones of Contention and Nationhood’, ‘Fragments of Redemption and Warfare’, and ‘Relics of Return and Renewal’—Raffa retraces the uses and abuses of Dante’s bones from the immediate aftermath in the fourteenth century to present-day. Along the way, he highlights the importance of Dante’s body and his body of work as sites of memory. As he writes in the introduction, ‘the restless bones of one of the world’s most influential travelers—in art as in life—also bear witness to historic changes in Italy and beyond. Dante’s remains, far from producing a fixed impression of the poet, have inspired worshipers of all stripes to fashion him in their own image’ (p. 20). From where we look in 2021, the transformation of Dante into Italy’s secular patron saint is complete. In this 700th anniversary year of the poet’s death, it is at the very site of his tomb that the Comune of Ravenna has begun a ‘perpetual reading’ of the Comedy: a canto of the poem will be read aloud in front of Dante’s tomb every day in perpetuity, a practice not unlike perpetual Eucharistic adoration for Catholics. (Not for nothing does Raffa mention an Italian poet who, in 1865, wrote that ‘the Comedy for us, like the Bible for the Israelites in exile, was the symbol of the homeland and nationality’ (p. 105)). In Chapter 1, Raffa recounts Dante’s death and burial in Ravenna, with his burial near the main church shortly after he died on the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. In the second chapter, ‘A marked grave’, Raffa hovers over the immediate reaction of Dante’s literary and political confreres to his death. Celebration was not universal, and to the condemnations of Dante was added another controversy: that of the Florentines’ abandonment of Dante. Boccaccio called on Florence to repatriate Dante, and ‘thus began the centuries-long tradition of calling on Florence to repatriate Dante’s bones to atone for the sin of having forced him to live and die in exile’ (p. 41). Raffa ends with an evocation of the epitaph on Dante’s Ravennese tomb, which derides Florence as a ‘mother of little love’ (p. 44). Beginning already in the late fourteenth century and increasingly in the fifteenth century, Florentines and eventually city officials made repeated requests to repatriate Dante’s bones, a period Raffa calls ‘Florentine remorse’, which he explores in Chapter 3. These efforts, even on the part of Lorenzo de Medici and an appeal made by Cristoforo Landino, editor of the elegant 1481 printed edition and commentary on the Comedy, fell on deaf ears (pp. 49–51). In Chapter 4, Raffa chronicles the ways in which Dante’s bones reflected Italian history and the political state of the peninsula. For example, in the early sixteenth century, Ravenna was under papal rule and the pope was none other than Leo x, who prior to his election had been the Florentine Giovanni de’ The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 250 romance languages · italian studies Medici, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. What better time, then, for Ravenna to make restitution of Dante’s body? (pp. 60–61) After an initial promise to do so, Leo x did not act right away. It was only after a follow-up letter in 1518 from the Sacred Academy of the Medici—humanist leaders of Florence—signed by such luminaries as Michelangelo, as well as poets and church hierarchs, that the Pope acted and an envoy was sent to Ravenna (p. 64). Despite Michelangelo’s promise to build for Dante in Florence a worthy tomb, the poet’s bones were not ‘translated’ back to Florence, for Franciscan friars moved them before the papal envoys could get to them. In a caper worthy of an avant garde Ocean’s Eleven, it is likely that the Franciscans broke through the chapel wall closest to their adjacent convent to carry away Dante’s remains. Had the Florentines, under another Medici Pope, this time Clement vii, wanted to explore further the repatriation of the poet, it is likely that history—in the form of the 1527 Sack of Rome—would have interrupted those plans anyway. In Chapter 5, Raffa notes that ‘Dante was an exile in death as in life’ (p. 72), with the Franciscans’ displacement of his bones inaugurating nearly four centuries of mystery. The intervening centuries witnessed much conflict over the care and ownership of the chapel in which Dante bones were (not), with conflict between the city of Ravenna and the Franciscans. Renovations to the chapel in 1692 reflected the ongoing battle for Dante’s legacy and renewed the enmity between Florence and Ravenna, with a new epitaph reading ‘exiled from Florence [Dante] was generously received by Ravenna, which honored him in death as it had rejoiced in him in life’ (p. 75). But where, in Ravenna, did they harbour Dante? Subsequent renovations in the late eighteenth century by Cardinal Gonzaga confirmed that the actual tomb was empty (p. 80). Raffa speculates that, while it is plausible that most of the Franciscans did not know about the empty tomb, conventual leadership had to have known. Regardless, at the end of the seventeenth century and beginning of the next, Dante’s tomb became a popular visit for the nascent Italian unification movement, with Vincenzo Monti and Vittorio Alfieri, among others, venerating Dante at Ravenna. Little did these patriots know, Dante’s bones had for some time been hidden in a passageway that had connected the chapel to the Franciscan church cemetery. The penultimate chapter of the first section, ‘Prophet of Italy’, retraces Dante’s adoption as the poet of unification, whereby the ‘memorial cenotaph’ in Santa Croce, writes Raffa, ‘marked the elevation of Dante to a symbol of the emerging Italian nation’ (p. 95). The subscription movement to erect a monument to Dante in Santa Croce was accompanied by literary tributes by Leopardi and Lord Byron, inaugurating a season in which Dante’s memory as a contested site between cities was transformed into a prophetic, unifying precursor to Italian nationhood. Raffa describes Stefano Ricci’s 1830 marble monument of Dante as ‘a triThe Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 251 umphalist vision of Italy’ (p. 101). Like the new monument in Florence, Dante’s tomb in Ravenna, too, underwent an ideological transformation. Raffa cites the uptick in enthusiasm for Dante in 1848 and 1859–1860, not coincidentally revolutionary years in Italy. Leaders of a now-united Italy, including King Victor Emmanuel ii, logged visits to Dante’s tomb in the wake of unification. In the final chapter of the first section, we learn of the transfer of united Italy’s capital to Florence in 1865, the same year as Dante’s 600th birthday, and of the ‘overtly political nature’ of the festivities planned to honour more Dante the Patriot than Dante the Poet. Though the celebration of Dante was a success, Florence again failed in its attempts to repatriate Dante’s bones, having been rebuffed by Ravenna. Cleverly, the mayor of Ravenna and its city council argued that unification made any claims on Dante’s bones from Florence null and void, for ‘in a free and united Italy, Dante was as much at home in Ravenna as anywhere else on Italian soil’ (p. 109). Just weeks later, Ravenna city officials, in response to the discovery near Dante’s tomb of a box with an inscription claiming to hold Dante’s bones, opened Dante’s supposed final resting place only to discover that it was ‘entirely empty’ (p. 121). The discovery of the box provided Ravenna with the perfect occasion—accompanied by pomp and circumstance—to hold an international celebration of the poet. Much of the reaction to these celebrations of Dante in Florence, Ravenna, and elsewhere follows the contours of nineteenth-century Italian political debates: the Church refused to exalt Dante as a republican patriot and prophet of a new, Liberal Italy, while proponents of the Risorgimento continued to hold him aloft as a poet of national unity. Raffa notes that Dante’s status as a national poet waned until the early twentieth century when, in the context of World War i Dante was again instrumentalized as a symbol of national unity. The second section of Dante’s Bones examines the use of Dante during World War i, on the occasion of the 600th anniversary of his death in 1321, and under fascism. Particularly interesting is Chapter 12, ‘Dante’s Duce, Mussolini’s Dante’, in which Raffa explores Mussolini’s use of Dante. Already in 1921, after yet another exhumation of Dante’s remains, Mussolini mentioned Dante and claimed him as an inspiration ‘not just for Italian nationhood but specifically for Fascism’ (p. 210). Mussolini, observes Raffa, followed Giuseppe Mazzini and Gabriele D’Annunzio in claiming Dante for his cause. Supporters of fascism seized on the various prophecies of the Comedy— among them the veltro and the ‘Five Hundred Ten and Five’ of Purgatory—to argue for Dante’s prediction of Il Duce’s arrival (p. 216). In addition to interpreting Dante to suit its needs, Mussolini’s fascist regime also contributed to renovations of Dante’s tomb. These renovations also resulted in the creation of a ‘Zona dantesca’ and a special feast (Sagra Dantesca), connecting the fascists evermore directly to contemporary celebrations of Dante. In the third and The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 252 romance languages · italian studies final section of the book, Raffa chronicles the current status of Dante’s bones, and notes yet another call to repatriate—this time only temporarily—Dante’s bones to Florence. As of this writing, the sommo poeta remains in exile. 4 Minor Works Stefano Carrai, Dante elegiaco. Una chiave di lettura per la ‘Vita nova’ (Florence: Olschki, 2020), 122 pp., is an economical essay, first published in 2006 and now reprinted, that proposes to categorize Dante’s libello, the Vita nova, as an elegy. It is one of two studies on the Vita nova by Carrai in 2020. Both of Carrai’s long essays on the Vita nova can be read profitably with Donato Pirovano’s essay ‘Vita nuova’, one of the many chapters that make up the handbook Dante, ed. by Roberto Rea and Justin Steinberg (Rome, Carocci, 2020). Pirovano counters Carrai’s definition of the libello as ‘elegiac’. Carrai first explores the many labels and generic influences that have been ascribed to the work of prosimetrum— from the vidas and the razos to a work of poetics—before concluding that they are insufficient. Nevertheless, he admits that the Vita nova will continue to defy reductive categorization. Carrai’s preference is to read the work as an elegy. He makes the case for this by reviewing contemporary works from a variety of genres that are considered elegies. The most convincing case is made by considering Guillaume de Conches (c. 1120), who in his accessus to his commentary on Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy—a long-held influence on Dante— writes that prosimetrum (the alternation of prose and poetry) in the tradition of Marziano Capella is a see-saw characteristic of the consolation, of which elegy is the umbrella genre: ‘In prosa igitur Boetius utitur ratione ad consolatione, in metro interponit delectationem, ut dolor removeatur’ (p. 21). Carrai’s proposal to read the Vita nova as an elegiac work was carried out in greater depth by Rossana Fenu Barbera’s study Dante’s Tears (Florence: Olschki, 2017) which argued for the centrality of weeping in proposing that Dante’s libello was a work of melancholy. Carrai, for example, points to the Vita nova’s ‘tonalità lacrimevole’ (p. 22) and notes the frequency of the verb piangere in the poetry of Dante’s little book. In fact, the action of crying appears almost immediately in Dante’s first integral work, the Vita nova, where the poet, from the ‘natural spirit’ in his liver, began to weep upon seeing Beatrice. Subsequently, the lord holding Beatrice in Dante’s dream and recounted in the sonnet A ciascun’alma presa is said to have begun to cry upon holding her. Even before the first poem in the Vita nova, then, the reader encounters four instances of piangere or its derivatives (piangere, piangendo, pianto, piangendo), and the word also appears in the first poem itself. According to Fenu Barbera, piangere is the third mostThe Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 253 used word holding semantic weight in the Vita nova (p. 4). Fenu Barbera argues that Dante’s weeping in the Vita nova is the result of melancholy, a disease that was roundly attested in medieval literature and against which crying itself was seen as a prophylactic, since melancholy was associated with the deadly sins. Carrai, too, notes the emphasis on words related to weeping, both in the poetry—Piangete, amanti, poi che piange Amore; O voi che per la via d’Amor passate; L’amaro lagrimar che voi faceste; Li occhi dolenti per pietà del core—and the prose (dolore, doloroso, dolorosa e dolente, lagrime e lagrimare, lamento, lamentanza, lamentare, lamentarsi, piangere, pianto, singulto, tristizia) of the Vita nova (p. 28). However, as is the case with Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia and Convivio, the duelling labels ‘melancholic’ and ‘elegiac’ need not be seen in opposition to each other; rather, they testify to the permeability of generic labels and the ultimate unclassifiability of Dante’s and other medieval texts. Following the first chapter and its study of the Vita nova and elegy, this slim volume contains two more chapters: ‘La testura di un racconto artefatto’ (pp. 43–76) and ‘Il rapporto tra poesia-prosa e la genesi del prosimetro’ (pp. 77–112). In the latter, Carrai argues that the ‘la coordinazione di prosa e poesia … non sembra aver attratt[a] granché l’attenzione degli studiosi’ (p. 77). (Since this book was first published in 2006, the relationship has begun to attract the interest of scholars, most notably in Jelena Tudorović’s 2016 Dante and the Dynamics of Textual Exchange: Authorship, Manuscript Culture, and the Making of the ‘Vita Nova’ (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), 248 pp.) In this third chapter, Carrai aims to calm the lacuna lamented by Picone and others. Carrai begins by emphasizing the composite nature of Dante’s auto-commentary: the original poems, the narrativization of the poems, and the division of the poems (p. 79). This composite nature was recognized early on by none other than Boccaccio, who severed the connection between the poems and the divisioni by relegating the latter to the margins of his copy of the Vita nova. In doing so, comments Carrai, Boccaccio also recognized a hierarchy between types of prose in the Vita nova: divisioni, which he deemed essentially glosses, and prose that is instead integral to the text. All things considered, the connective prose, writes Carrai, allows the action to progress and ‘tende ad essere stilisticamente solidale con i versi’ (p. 85). More than a commentary, the prose expounds on the poetry that it accompanies, most notably in the canzone Donna pietosa e di novella etate, wherein ‘la strategia della prosa risulta in parte quella di completare il laconico discorso in versi, in parte quella di rafforzare il tessuto stilistico e sostenere la tonalità prevalente della poesia’ (p. 88). In addition to the relationship between poetry and prose, Carrai also considers Dante’s use of poetic genres such as the canzone, the sonnet, and the (lone) ballata. For one, only the sonnets are commissioned. Dante’s use of the ballata for the first poem addressed The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 254 romance languages · italian studies directly to Beatrice, via Love, Carrai surmises, is due to its occupying the middle rank between the sonnet and the elevated style of the canzone (p. 94). Carrai reminds us also that Antonio da Tempo qualified the ballata as ‘quia fiunt ut plurimum gratia amoris venerei’ (p. 95). In the penultimate section of the chapter, Carrai explores the birth of the libello, that is, he considers whether all the poems preceded the idea of a little book in prosimetrum, or whether, on the contrary, ‘qualche brano poetico sia stato scritto successivamente alla concezione del libro’? (p. 97). He seems to lean towards ‘yes’. Finally, Carrai turns his attention to the verb tenses that Dante uses in the prose and discovers a possible fil rouge connecting those poems that have a dream-like or oniric character: a quintet of poems for which Dante uses primarily the present tense as opposed to the past tense, employed in the explicative prose accompanying almost all other poems (pp. 101–102). Carrai’s short book adds another dimension to our study of Dante and his so-called ‘minor’ works. Stefano Carrai, Il primo libro di Dante. Un’idea della Vita nova (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2020), 141 pp., continues the author’s exploration of Dante’s libello and begins, in the introduction, by contending that, even absent the Commedia, Dante would have garnered literary fame with only the Vita nova, which represented a ‘concezione del rapporto amoroso tutta ispirata al principio della nobiltà del cuore in un clima anche socialmente nuovo e favorevole ad accoglierla’ (p. 9). This new climate—specifically Giano Della Bella’s political opening to the arti—involved Dante directly and coincided with the composition of the Vita nova, for in the same months in which the libello was being finished, Dante himself joined the speziali to take advantage of Giano’s promulgation. With Erich Auerbach, Carrai minimizes the autobiographical nature of the Vita nova, whereas Alessandro Barbero in his new biography, Dante, will mine it fruitfully for innumerable biographical references. Rather, writes Carrai, even seemingly autobiographical vicissitudes in the Vita nova reference, for example, Andrea Capellano’s De Amore, and parrot the love-manual’s precepts. As he does in the above-reviewed Dante elegiaco. Una chiave di lettura per la Vita nova, Carrai highlights the centrality of Beatrice’s death and the ‘tema funebre’ that results in what he calls the ‘stile in senso lato elegiaco’ on the model of Boethius’s Consolatio Philosophiae (p. 13). Nevertheless, Carrai puts forth a slight re-evaluation of his description of Dante’s libello as elegiac (first written in 2006 and reprinted in 2020) on the basis of Dante’s promise to ‘dicer di lei quello che mai non fue detto d’alcuna’, writing that ‘più che il libro dell’elegia, la Vita nova voleva essere il libro del superamento dell’elegia’ (p. 14; emphasis mine). Apart from the discussion of elegy, Carrai’s two essays have the greatest overlap in their discussions of prosimetrum. In Dante elegiaco, Carrai discusses ‘Il rapporto tra poesia-prosa e la genesi del prosimetro’ in the third and final chapter; in Il The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 255 primo libro di Dante, he considers ‘La cronologia del prosimetro’ in the first of seven brief chapters. Pasquale Stoppelli, L’equivoco del nome. Rime incerte fra Dante Alighieri e Dante da Maiano (Rome: Salerno, 2020), 104 pp., gathers six essays—published previously but reworked—that consider primarily the 1527 ‘Giuntina di Rime Antiche’, an enormously influential volume of poetry by the Giunti of Florence and edited by Bardo Segni containing the poetry of Dante’s Vita nova, as well and poems by Cavalcanti, Guinizelli, Guittone, the poets of the scuola siciliana, and others. In all, 88 per cent of the book’s poems were unedited at the time of publication. But Stoppelli’s focus is on the poems attributed to Dante da Maiano, who is otherwise unattested in the manuscript tradition. In particular, Stoppelli explores the section of the volume dedicated to a series of tenzoni between Dante da Maiano and Dante Alighieri. The departure point for this economical volume is Stoppelli’s 2011 work on the Fiore and its attribution to Dante, or not, for Stoppelli is one of the few modern critics to make a strong philological case for its non-Dantean paternity. In fact, he proposes that the most probable author of the Fiore is none other than Dante da Maiano. From there were born further reflections on Dante’s Rime, chief among them the tenzoni with Dante da Maiano, which as noted above, have their editio princeps in the 1527 Giuntina and have no extant manuscript tradition. After a chapter on the methodological nature of attributions (‘Metodologia delle attribuzioni letterarie’) and an excursus on those works that are attributed in the main to Dante but whose authorship is still disputed (Il fiore, Detto d’amore, the Epistle to Cangrande, the Questio de aqua et terra), Stoppelli dedicated three of the remaining four chapters to the 1527 Giuntina and specifically to the question of Dante’s tenzoni with Dante da Maiano. Chapter 3, ‘La Giuntina di Rime Antiche’, discusses briefly the textual and para-textual aspects of the Giuntina and its editor, Bardo Segni, himself a practicing poet, as well as the collection’s manuscript tradition and its role in the study of early Italian lyric. Chapter 4, ‘Nuove ipotesi sulla tenzone del “Duol d’amore”’, uses the sonnet Non canoscendo, amico, vostro nome, attributed in the Giuntina to Dante Alighieri, as a case-study for the attribution of the poems to Dante. As Stoppelli comments at the end of Chapter 3, he will attempt to resolve the question of ‘Dante guittoneggiante’ in these so-called early poems. In a few words, Stoppelli wonders why, in a five-sonnet tenzone of seventy verses, fully thirty-seven are dedicated to the praise of the interlocutor—for the most part, praise of Dante on the part of Dante da Maiano—when Dante’s sonnets are supposed to be representative of ‘early’ Dante and reflective of his guittonismo. How can it be, then, that young Dante merited such extended praise? (p. 55). Stoppelli reminds us that Salvatore Santangelo first proposed that the order of the tenzone had been inverted, that is, that it was young Dante praising effusThe Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 256 romance languages · italian studies ively a mature, established Dante da Maiano rather than the other way around. This hypothesis has been discarded—do we really believe that a contemporary or near-contemporary of Dante would have been completely absent from the manuscript tradition of early Italian lyric if he had been so venerable—and there remain other problematic indices of post-guittonismo, that is, stilnovismo, especially the rhyme scheme, which Stoppelli notes is markedly stilnovist. Since Stoppelli began thinking about the Dante-Dante tenzoni after proposing the attribution of the dubious Fiore to Dante da Maiano, he concludes the third chapter with an alternative hypothesis that runs counter to the idea that the authorship of the tenzoni’s parts were inverted or that the Giunti and Bardo Segni erred (after all, Stoppelli notes appropriately, the Giunti were considered so authoritative that Arnaldo De Benedetti, in his influential 1912 study of the volume, wrote that ‘la Giuntina si dovrà di qui innanzi interrogare come s’interroga un codice’ (p. 52)). On the contrary, Stoppelli advances the idea that Dante da Maiano is the author of the entire tenzone. In support, he focuses on v. 7 of Non canoscendo, amico, vostro nome. The seemingly illogical lectio in the Giuntina (‘fornomo’), which received various editorial corrections over the years, is, according to Stoppelli, ‘for nom’ò’, a reading he recovers by making recourse precisely to the Fiore: ‘fuor di tu nome’ (v. 9, l’Amante) (p. 63). If it were otherwise, argues Stoppelli, because of the Stilnovist aspects of the exchange, ‘dovremmo immaginarci un Dante maturo che segue la scia di un mediocre rimatore dei cui testi non risulta alcuna circolazione’ (pp. 63–64). It is, then, with the study of both the formal aspects of the tenzone and through a methodical comparative analysis that the author comes to his conclusion. In the final chapter, ‘Per un nuovo profilo di Dante da Maiano’, Stoppelli investigates the biographical profile of Dante da Maiano and asks why, with such a massive production in the songbook dedicated to him in the Giuntina, Maiano was absent from, for example, ms Vaticano Latino 3793. This is especially perplexing because, as we learn from the Giuntina, Dante da Maiano is one of only three poets—the others being Dante’s ‘primo amico’ Cavalcanti and either Cino da Pistoia or Terino da Castelfiorentino—to respond to A ciascun’alma presa e gentil cor, the first sonnet of Dante’s Vita nova. If Dante da Maiano were so well-known as to be among the only respondents to the first sonnet in a work with which Dante entered the poetic elite of Florence, what explains his absence? Stoppelli proposes that, as with the other tenzoni in the 1527 Giuntina, Dante da Maiano’s ‘response’ to Dante’s A ciascun’alma presa may be a posthoc ‘esercizio privato scherzoso’ (p. 87). This is especially the case because of the intertextuality between v. 8 (‘a ciò che stingua e passi lo vapore’) of Dante da Maiano’s response (Di ciò che stato sei dimandatore) and Inferno 14.35–36, which according to the Tesoro della Lingua Italiana delle Origini contain the The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 257 only two instances, in verse, of ‘estinguere’ and ‘vapore’ together (p. 87). In the end, Stoppelli concludes, if all the sonnets in the tenzoni with Dante da Maiano were to be attributed to him and not to Dante, Dante’s reputation would be the better for it. Nuove inchieste sull’epistola a Cangrande, ed. by Alberto Casadei (Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2020), 234 pp., represents the latest in the editor’s attempt to understand the nature and attribution of what is referred to as ‘Dante’s Epistle xiii’. It follows closely 2019’s Altri accertamenti e punti critici, ed. by Casadei (Milan: FrancoAngeli, 2020), 296 pp., whose first section explores the same Epistle to Cangrande and concludes that, while the first part of the letter may be authentic, the latter part was written by someone other than Dante: ‘l’ipotesi della falsità dei successivi (paragrafi) appare, allo stato attuale, largamente più economica’ (p. 102). The volume contains eight chapters: Giuseppe Indizio, ‘Riflessioni biografiche e di metodo su un vecchio problema: Dante a Verona’ (pp. 11–26); Piermario Vescovo, ‘Minosse, l’uscita dall’Egitto, i ‘sensi’ del testo e il percorso ‘comico’ dell’allegoria’ (pp. 27–48); Marco Signori, ‘Qualche precisazione sul senso allegorico nell’Epistola a Cangrande (e in altri commentatori)’ (pp. 49–76); Fabrizio Franceschini, ‘Ancora sull’Epistola a Cangrande, Guido, Lana: il subiectum della Commedia’ (pp. 77–104); Eugenio Refini, ‘Dante liberrimus vatum: appunti su tradizione oraziana e varietà stilistica tra Epistola a Cangrande e Prima Egloga’ (pp. 105–128); Alberto Casadei, ‘‘Canticam … offero’ e altri problemi esegetici’ (pp. 129–152); Silvia Corbara, Alejandro Moreo, Fabrizio Sebastiani, and Mirko Tavoni, ‘L’Epistola a Cangrande al vaglio della computational authorship verification: risultati preliminari (con una postilla sulla cosiddetta “xiv epistola di Dante Alighieri”)’ (pp. 153–194); and Susanna Barsella, ‘Il moto delle “etterne rotte”: la cosmologia dantesca tra la Commedia e l’Epistola xiii a Cangrande della Scala’ (pp. 195–224). Like all biographers of recent vintage, Indizio lays bare the reality that we really don’t know all that much, with certainty, about Dante’s biography. In his essay, Indizio proposes to examine the evidence of Dante’s ‘universally accepted’ two stays in Verona. He mentions that, methodologically, there are five categories of documentary evidence: biographical allusions in Dante’s own work; documents pertaining directly to Dante: historical documents pertaining indirectly to him: and contemporaneous literary texts (correspondence, chronicles and the like) (pp. 12– 14). Indizio will, then, seek to demonstrate what we know of Dante in Verona using these categories. What evidence do we have of a visit by Dante between the end of 1302 and the late summer/early autumn of 1303, with the objective of political and military diplomacy on behalf of the White Guelphs? And what evidence do we have of a subsequent return to the city between the end of 1315 and the winter of 1319–1320? But the most fascinating contribution is that of the quartet responsible for the machine learning article ‘L’Epistola a The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 258 romance languages · italian studies Cangrande al vaglio della computational authorship verification: risultati preliminari (con una postilla sulla cosiddetta “xiv epistola di Dante Alighieri”)’ (pp. 153–194). This is so both because of the methodology and because of the authors’ conclusion. Rather than attribute the letter to Dante in its entirety or, as has become increasingly the case, only the first section while proposing the second’s authorship to a later interpolator, the authors conclude that neither the first section nor the second is Dante’s. For the algorithm, the authors chose to treat the first part of the epistle (paragraphs 1–13) and the second part (paragraphs 14–90) as distinct texts, because, as they write, ‘molti studiosi hanno dato giudizi di autorialità diversi sulle due sezioni; in particolare, convinti della natura spuria della seconda parte dell’Epistola xiii, ammettono però che la prima parte possa essere ascritta a Dante Alighieri’ (p. 164). In order to ascertain the potential Dantean paternity of either section, two separate bodies of texts were chosen. Thus, for part one, the Dantean texts in Latin consisted of his epistles of certain attribution, while the non-Dantean group featured works by Clara Assisiensis, Guido Faba, Pietro della Vigna, and Giovanni Boccaccio. For the second part of the Epistola xiii, Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia and Monarchia were measured against Latin texts by Ryccardus de Sancto Germano, Guido Faba, Boncampagno da Signa, Giovanni del Virgilio, Guido Da Pisa, Bevenuto da Imola, and many others (pp. 166–167). For both the first and the second part, the group of non-Dantean texts chosen was nevertheless very similar to the first and second sections of the Epistola a Cangrande, that is, characterized by similar linguistic traits, because ‘se i testi non danteschi utilizzati per il training fossero linguisticamente molto diversi dai testi di training danteschi, un qualsiasi testo anche vagamente simile alla produzione dantesca verrebbe riconosciuto come inequivocabalmente dantesco’ (p. 165). In both cases, the authorship verification favoured an attribution to someone other than Dante for both parts. This contrasts with the great majority of critical opinion, which holds either that the letter is Dante’s or that at least the first thirteen paragraphs are to be considered authentic. Interestingly, while more critics maintain that Dantean authorship is more likely than not for the first part, the results of the authorship verification have ‘un maggior grado di certezza per Ep i (0.24) che per Ep ii (0.39)’, meaning that, according to the algorithm created by the authors, the proposal for an attribution to an author other than Dante for the first part of the epistle is actually more certain that such an attribution for the disputed second part (p. 170). (Though they later clarify that this certainty is due to the accuracy of the corpus used to determine the first part’s paternity (p. 181).) Despite these findings, the authors also broke down the experiment on the level of individual paragraphs, the results of which propose ‘Dante, per entrambi i testi [parts one and two of the epistle], fra The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 259 gli autori “meno improbabili”’ (p. 171). Helpfully, the entire Epistle xiii is reproduced with the results of the paragraph-level experiment and the relative likelihood of Dantean paternity indicated by darker (more likely Dante) and lighter shading (less likely Dante) (pp. 173–180). In the end, the authors sum up the research thus: ‘la risposta alla domanda ‘È di Dante o no?’ è: ‘più no che sì’. Ma, delle due, la parte ‘meno’ dantesca dell’Epistola è la prima’ (p. 183). Le lettere di Dante. Ambienti culturali, contesti storici e circolazione dei saperi, ed. by Antonio Montefusco and Giuliano Milani (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), 626 pp., is a marvellous collection of essays devoted to Dante’s Latin epistles. After an introduction by Montefusco, the volume has two sections, ‘Tradizione e critica del testo’ and ‘Dante e l’ ars dictaminis’, each containing essays on the letters and philology and then on rhetoric and the letters, respectively. Part C features eighteen rich essays on the letters themselves, subdivided into three categories: ‘Dalla militanza con i Bianchi al soggiorno in Lunigiana’; ‘Gli anni dell’impero’; and ‘Proiezioni profetiche e impossibilità di tornare’. Montefusco opens the introduction with a brief summary of Dante’s letters and the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century scuola storica, and reflects on Francesco Novati’s lectura on the epistles, published in 1905. Novati, writes Montefusco, ‘parlava delle lettere dantesche quasi come di un relitto navale incagliato nelle acque della Storia’ (p. 2), but nevertheless ‘coglieva l’occasione sia per sollevare problemi irrisolti … sia per fare nuove acquisizioni sul fronte della storia del dictamen e dell’influsso di quest’ultimo sulla nascente prosa volgare in toscano’ (p. 3). In other words, whatever the position of Dante’s so-called minor works relative to the Comedy, the Vita nova, and the Convivio, and whatever the methodology of the positivist, historicist school, the letters were being discussed and studied. Given the recent biographical turn, notes the author, the study of the letters has benefited from this increasing interest, even if ‘l’interesse per i testi che sono al centro di questo volume è rimasto flebile e mai monografico’ (p. 3). In order to calm this gap, Montefusco and Milani desire to dedicate an entire volume to these important texts. Of great interest is the choice they make to exclude not only the letter to Guido da Polenta, but also the much-discussed Epistola a Cangrande, to whom we devoted substantial space above. Why do they exclude it? For both stylistic reasons (‘lo squilibrio tra prima e seconda parte’) and philological motives (‘è soprattutto la natura del testo, nonché la sua trasmissione indipendente rispetto al resto del corpus, ad averci convinti a escluderla dal nostro studio’ (p. 6)). The findings by the quartet of authors of ‘L’Epistola a Cangrande al vaglio della computational authorship verification: risultati preliminari (con una postilla sulla cosiddetta “xiv epistola di Dante Alighieri”)’ (pp. 153–194) in the volume edited by Casadei should give further confidence to Montefusco and Milani of the soundness of their decision to exclude the The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 260 romance languages · italian studies crux desperationis of Dante Studies. Montefusco also explores the reception and transmission of Dante’s epistles, a task made more difficult by their adventitious conservation, in contrast to Petrarch’s careful collecting for posterity. Thus, the letters were conserved and/or transmitted and read by letterati, notaries, and political figures, including Cola di Rienzo and Petrarch himself (p. 8). The ‘asystematic diffusion’ of the letters is attested to by the scarce manuscript tradition, almost all ‘tradizione unica’. Only letters five and seven have multiple witnesses, with the latter also having been translated into the vernacular twice in the fourteenth century. The letters copied by Boccaccio were done so in Naples, while the letters gathered in ms. Palatino Latino 1729—which account for 70 per cent of Dante’s epistolary production—come from the cancelleresca tradition and were likely copied in Perugia, possibly by the manuscript’s onetime owner Francesco Piendibeni da Montepulciano (p. 10). In the third section of the introduction, the author interrogates the vernacularization of the seventh epistle and the importance of Florence as a site of transmission for Giovanni Villani’s Nuova cronica. In the fourth section, Montefusco considers briefly the letters that are not there, including the letter mentioned in the Vita nova that Dante ‘scrisse alli principi de la terra’, as well as the letter mentioned by Bruni in his Vita di Dante. According to Montefusco, there is little reason to doubt that this letter existed, for Dante’s epistles did circulate and/or were conserved in Florence, and Bruni describes contents and style that are characteristically Dantean. The monographic focus of this collective volume is a welcome addition to Dante Studies. 5 Fortuna Dante Satiro. Satire in Dante Alighieri’s ‘Comedy’ and Other Works, ed. by Fabian Alfie and Nicolino Applauso (Lanham: Lexington, 2020), 230 pp., represents the first of its kind: an exhaustive exploration of the use of satire throughout Dante’s works. The book features two sections, ‘Satire in Dante’s Comedy’ and ‘Satire in Dante’s Minor Works’, as well as a coda by Arielle Saiber that considers ‘The American Legacy of Dante’s Satire’. The title of the collection takes its inspiration from the epithet that Dante himself gave to Horace in Inferno 4.89: ‘Orazio satiro’ and applies Horace’s appellation to Dante in the Comedy and elsewhere. In their introduction, editors Alfie and Applauso retrace the migration of the use of satire from the classical world to the medieval period, and note that Roman rhetorician Quintillian distinguished the Greeks from the Romans by way of the latter’s use of satire. Despite its classical, and especially Roman, roots, Alfie and Applauso write that ‘satire was clearly redefined in the The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 261 Middle Ages as one of the canonical literary genres’ (p. 2). As far as it regards Dante, although satire is not one of the most common terms associated with him, the label is not anachronistic. Numerous fourteenth-century commentators report the medieval definition of satire as ‘reprehendere vitii’, that is, to ‘reprehend vice’ and to ‘hold unacceptable behaviors up for public ridicule’ (p. 3). This is a definition that finds itself at home in much of Dante’s work, so much so, write the editors, that ‘Dante might have just as easily named his magnum opus “satire” instead of Commedia’ (p. 4). No matter, for in the thirteenth century, even comedy became associated with satire. Nevertheless, Dante’s use of satire is not limited to his epic poem, but rather ‘runs through [his] entire literary production’ (p. 5). In order to demonstrate the ubiquity of satire, Alfie and Applauso choose the third canticle, Paradise, not traditionally associated with the genre. In Paradise 29, an indignant Beatrice deploys invective against the vacuity of preachers. Satire, then, is used strategically and occasionally by Dante, in all situations. In the first section of the volume, Franco Suitner, ‘The Ontoso Metro of Dante’s Sinners: Inferno 7’ (pp. 21–31), reads Inferno 7 as suffused with a vituperative character. Ronald Martinez, ‘Inverted Popes, the Apostolic Succession, and Dante’s Vocation as Satirist’ (pp. 33–53), studies Dante’s satirical representation of the popes and its relationship to Horace’s ars poetica. Mary Watt, ‘“Ed elli avea del cul fatto trombetta” (Inferno 21.139): Satire and Sodomy in Dante’s Inferno’ (pp. 55–71), takes on the question of sodomy in Inferno 15 as well as a similar depiction in Inferno 21. Finally, Maggie Fritz-Morkin, ‘“Se io mi trascoloro, non ti maraviglia”: Peter’s Invective and colores rhetorici in Paradiso 27’ (pp. 73–90), considers the invective-filled Paradiso 27 and argues that it is not an outlier, but instead strictly connected to the surrounding cantos. In the second section, which examines satire in Dante’s other works, Anthony Nussmeier, ‘“Ut exinde potionare possimus dolcissimum ydromellum” (dve 1.1.1): Dante satiro and the De vulgari eloquentia’ (pp. 93– 115), shows how satire functions as one of the principal modes of Dante’s Latin treatise De vulgari eloquentia. Beatrice Arduini, ‘Invective and Emotional Tones in Dante’s Convivio’ (pp. 117–131) explores the shift of tone and the strategic deployment of invective in the Convivio to argue that Dante makes recourses to satire only when any hopes to return to his beloved Florence are dashed. Fabian Alfie, ‘The Conundrum of Genre: Dante’s Doglia mi reca’ (pp. 133–145), argues that the example of Dante’s canzone Doglia mi reca puts satire in the high style, and not, as typically thought, in the low, humble style. Nicolino Applauso, ‘“Scelestissimus fiorentinis”: Violence, Satire, and Prophecy in the ars dictaminis and Dante’s Political Epistles’ (pp. 147–167), considers satire and Dante’s epistles, and the strict connection between Dante’s reprehension of vice and the art of letter writing in the medieval period. The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 262 6 romance languages · italian studies Journals and Journal Articles Teaching Dante. Special Issue Published in Religions, ed. by Christopher Metress (Basel: mdpi, 2020), 124 pp. gathers together select contributions from the Third Biennial Teaching the Christian Intellectual Tradition Conference: ‘Teaching Dante’, held at Samford University 25–27 October, 2018, and includes reflections on ‘perennial pedagogical problems’, successes, and challenges in teaching Dante and, most frequently, his epic poem. Albert Russell Ascoli, ‘Starring Dante’ (pp. 9–28), considers Dante’s ‘double role as humble student and prospective teacher of others’ and deals with the paradox of a poem imbued with caritas that at the same time ‘appears as the absolute height of selfaggrandizement’. Matthew Rothaus Moser, ‘Understanding Dante’s Comedy as Virtuous Friendship’ (pp. 29–37), proposes that the relationship between Dante and his reader be understood as one of ‘virtuous friendship’, and that this aspect can be marshalled to teach the poem’s emphasis on moral and religious transformation in the classroom. Sean Gordon Lewis, ‘Mathematics, Mystery, and Memento Mori: Teaching Humanist Theology in Dante’s Commedia’ (pp. 39–51), undertakes one other problem faced by all but a few of us who teach Dante: How does one teach a work suffused with theology and written in a religious milieux when ‘undergraduates have little or no religious formation’? This is the case at both secular and, unfortunately, religious universities. Bryan J. Whitfield, ‘Teaching Dante in the History of Christian Theology’ (pp. 53–66), explores the integration of Dante into disciplines outside literature, specifically into the study of theology. He suggests ways of reading Dante as a ‘theologian’—after all, more than one contemporary, from Giovanni del Virgilio to Giovanni Boccaccio, described Dante as ‘theologus’—and models ways of using the Comedy, especially Paradise, to illuminate medieval theology. Sara Faggioli, ‘“Florentino Ariza Sat Bedazzled”: Initiating an Exploration of Literary Texts with Dante in the Undergraduate Seminar’ (pp. 67–80), proposes to use the concept of love in the Comedy as a frame for understanding the same topos in authors as diverse as St. Francis of Assisi, Vittoria Colonna, William Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Flannery O’Connor, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Julie Oooms, ‘Three Things My Students Have Taught Me about Reading Dante’ (pp. 81–92), discusses the reciprocal nature of her experience with Dante in the undergraduate classroom, and highlights mentorship, suicide, and the question of the intellect and expertise as occasions for reflection as a teacher of Dante. Dennis Sansom, ‘“Where are we going?” Dante’s Inferno or Richard Rorty’s “Liberal Ironist”’ (pp. 93–102), compares the moral reasoning and imperative in Dante and in Richard Rorty, and argues that ‘Dante’s [moral reasoning as represented by Inferno] is superior in terms of accounting for The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263 duecento and trecento (dante) 263 the structure of moral reasoning to Richard Rorty’s promotion of the “liberal ironist” ’. Jane Kelly Rodeheffer, ‘“And Lo, As Luke Sets Down for Us”: Dante’s ReImagining of the Emmaus Story in Purgatorio xxix–xxxiii’ (pp. 103–107), reads Dante’s journey through the earthly paradise at the end of Purgatory as a retelling of the Road to Emmaus passage in the Gospel of Luke. Paul A. Camacho, ‘Educating Desire: Conversion and Ascent in Dante’s Purgatorio’ (pp. 109–124), is a learned and lucid account of types of love and desire in Dante and specifically in Purgatory. Especially appreciated are the connection the author makes between geography and theology and the centrality of the Discourse by Virgil and its importance to the Commedia as a whole. Virgil’s Discourse on Love in Purgatorio 17 is ‘Thomistic in structure’ and ‘the scholastic distinctions presented here […] result from Thomas’ characteristic and daring synthesis of Aristotelian and Platonic-Augustinian concepts’ (p. 112). There is an even greater argument for the Thomistic reading of the cantos covering the midpoint of the poem because, as Charles Singleton and most recently Christian Moevs have pointed out, the only two instances of the Thomistic libero arbitrio are found at a remove of 25 terzine (75 verses) from that exact midpoint of the Commedia (Purgatorio 16, v. 71 is 25 tercets from Purgatorio 17, v. 1, and Purgatorio 18, v. 74 is 25 tercets from the end of Purgatorio 18). The Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies 82 (2022) 235–263