9801 2 Chan Sek Keong Equal Justice and s 377A of the Penal Code (Published on e-First 14 October 2019)

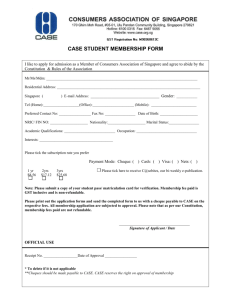

advertisement