Unfck-Your-Anxiety-Using-Science-to-Rewire-Your-Anxious-Brain-by-Faith-G

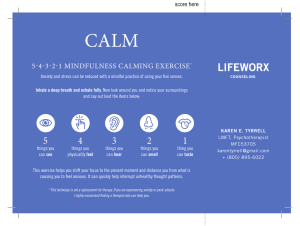

advertisement