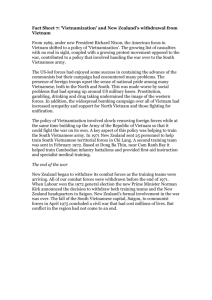

SOURCE A New Zealand soldiers of W3 Company about to head out on Operation Townsville during the Vietnam War, 1970. Source reference details: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/infantry-operation-vietnam-1970 SOURCE B Rest and recreation In Vietnam, New Zealand infantrymen and gunners spent a much higher proportion of their time on operations than soldiers in previous wars did. In the first half of 1967, members of V Company and 161 Battery spent more than 80 per cent of their time in the field, with little time dedicated to rest and recreation. Most downtime between operations was spent inside the army base camp which was a chance for men to rest and recuperate without civilian contact. New Zealand servicemen and civilians relax inside the Kiwi Club in Saigon, circa 1971 (Photo taken by Martin Thompson). While men were relatively secure ‘at home’ [in the camp], the constant shadow of possible attack meant staying on edge (even when they were meant to be off-duty), with perimeter patrols being part of the ‘at rest’ routine. For most, rest and recreation in country meant a few hours enjoying a concert at Luscombe Bowl or a few days in nearby Vung Tau shopping, indulging in the local bar scene, or socialising at allied service clubs. Most received a leave and accommodation pass for rest and recuperation out-ofcountry, perhaps in Thailand, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Philippines or Singapore. Very few regular soldiers returned home to New Zealand on leave. Source reference details: https://vietnamwar.govt.nz/nz-vietnam-war/rest-and-recreation SOURCE C Two Cambodian boy soldiers trained by NZ and US troops in Vietnam, nicknamed "Trash Can" and "Herman" by their American instructors. They are wearing cast-off US fatigue uniforms. Around 100 boys, some aged as young as 9 and 10 were trained. An American said "The kids make good trainees. They are keener than most of the others because they think it's a game." Source reference details: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/118263775/the-last-most-shameful-chapter-of-nzs-involvement-in-the-vietnam-war SOURCE D Notice for a public protest meeting at Myers Park, Auckland, to discuss New Zealand's involvement in the war in Vietnam and "Should NZ Troops be withdrawn?". Organised by the Auckland Peace for Vietnam Committee, Auckland. This poster notice was published around 1967-1970 Source reference details: https://digitalnz.org/records/39000504/vietnam?fromstory=5bb172fcfb002c627d9f5c34 SOURCE E Dr Peter Smith was a New Zealand doctor and the leader of a voluntary surgical team, based at Qui Nhon hospital in South Vietnam. This is part of his report from March 1969: “Had a three-year old die on me today. She came in with her guts torn apart by a grenade. Her mother, just a girl really, was with the child all the time, helping us to try and save her, and it was not until the child had died that we realised that the mother too had several wounds herself. The terrible sight of the dying child in the arms of the injured mother was most upsetting. It is horrible to think that our own troops will be inflicting the same sort of wounds on the same sort of people.” Source reference details: Excerpt from report by Dr Peter Smith, written in March 1969. Found in book by Historian Graeme Ball, Big World, Small Country: The 20th century and New Zealand’s place in it, published in 2013, page 327. SOURCE F Infantrymen of the 6th RAR/NZ (Anzac) Battalion descend from helicopters at a landing zone in Vietnam in August 1969. New Zealanders and Australians fought side by side in Vietnam. The New Zealand infantry companies formed a battalion with companies of the Royal Australian Regiment. New Zealand's 161 Battery also routinely provided artillery support to Australian units. For most of the war the artillery and infantry units were based at Nui Dat, the Australian base in Phuoc Tuy province, south-east of the city of Saigon. Source reference details: https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/34539/infantrymen-in-vietnam-1969 SOURCE G The other enemies In addition to the Viet Cong (the enemy North Vietnamese forces fighting in South Vietnam), the New Zealanders faced other ‘enemies’ too: spiders, snakes, lizards, weasels, rats, noisy frogs, scorpions, fleas and mosquitos. “One night an almighty scream pierced the air. The commotion had just subsided [settled down] when someone was heard to whisper “Get the bloody thing off my chest”. When they investigated, the gunners found one of the boys stretched out on his bed with a cobra snake coiled up on his chest sound asleep. It took two hours for them to organise his rescue by using smoke, but then the snake woke and slithered off on its own.” On other occasions, three men were helicoptered out after being stung by scorpions: ‘It’s like your body is being paralysed’. Source reference details: Book by Historian Graeme Ball, Big World, Small Country: The 20th century and New Zealand’s place in it, published in 2013, page 330. SOURCE H The Vietnam force training at Waiouru, NZ. Soldiers can be seen manning three field guns. Photographed by Morris James Hill in June 1965. Source reference details: https://digitalnz.org/records/22709187/vietnam-force-training-with-field-guns-waiouru SOURCE I Out on patrol For Victor (V) Company, most actions involved patrolling and ambushing. Most of the time they did not see anything of the Viet Cong (the enemy North Vietnamese forces in South Vietnam), which was frustrating. One soldier recalled: “A day on operations was from before first light in the morning until after last light at night, 12-14 hours. Sometimes the entire time was spent patrolling, at other times several days were spent in an ambush position. The day started with “stand-to” [when soldiers assume positions to resist a possible attack] about half an hour before first light, when we all got up and in our shell scrapes or pits until half an hour after first light; this was generally about 0600 or 0630. We then either had breakfast and got ready to move, or moved straight away and breakfasted about half an hour to an hour further on. Patrolling went on until the late afternoon, when the platoon would stop, go into a defensive position… and prepare for the night. Dinner would be eaten just before dark and half an hour before last light we would stand-to again until half an hour after last light. Following stand-to everybody went to bed except for the ‘senturies’ who were soldiers stationed to keep guard during the night.” Patrolling was mentally and physcially exhausting, and after ten days out, efficiency dropped noticeably. Ambushing proved more effective at killing the enemy than patrolling: ‘You set a trap and then wait’. Source reference details: Book by Historian Graeme Ball, Big World, Small Country: The 20th century and New Zealand’s place in it, published in 2013, page 331. SOURCE J Map of the Battle of Long Tan. This had been a ferocious battle fought against almost impossible odds. On the afternoon of 18 August 1966, a single infantry company of 108 mostly inexperienced Australian and New Zealand soldiers engaged with a regiment of 2,500 battle-hardened Viet Cong and North Vietnam army troops. and came out victorious. The New Zealand artillery provided crucial support for the Australian soldiers. The battle lasted 3 hours and over 3000 rounds of artillery were fired on the Viet Cong positions. Almost surrounded, outnumbered 10 to one, the ANZAC forces withstood Viet Cong attacks in the pouring rain and were able to defeat the Vietnamese, with 18 Australians killed and 24 wounded. At least 245 North Vietnamese died and over 500 were wounded. Source reference details: https://www.historynet.com/battle-of-long-tan-how-australians-and-new-zealanders-beat-odds/ SOURCE K Anti-war protesters gather outside the Auckland Town Hall, 12 May 1971. The placards they carry make explicit [clear and obvious] claims about the actions of New Zealand forces in Vietnam and how they feel about them and their actions. SOURCE L Booby Traps of the Vietnam War Jul 6, 2018 Matthew Gaskill, Guest Author Photo Left: Young North Vietnamese Militiawomen learn how to set booby traps. Photo Right: An exhibition of the different types of booby traps laid all over the Cu Chi site (in Saigon). For centuries, men have employed booby traps of one sort of another. Most but not all of the time, it is the weaker side that is using them in defense. In Vietnam, the Viet Cong guerrillas (the “VC”, or “Charlie”, as they were called by the Americans) and the North Vietnamese Army (“NVA”) were immeasurably outgunned by the forces of the United States and its allied contingents. In 1968, half a million American troops were in the country. The American side had more fire power, on the ground and in the sky. So is it any wonder that the Viet Cong/NVA put great effort in booby traps? There are a number of benefits to them: 1) they’re cheap, 2) they are relatively simple to make and use, meaning that virtually anyone can make one, 3) many were not designed to kill, but maim, requiring other men to care and remove the wounded man. And a wounded man spreads the word about how he got wounded. It’s one thing to enter a battle that’s already raging; a soldier knows danger is present. Walking through the woods with no enemy for miles around on a nice quiet day, then suddenly getting your leg blown off? Psychologically terrifying. 4) most of the booby traps used by the VC worked on their own – no one needed to set them off or be around when they did. And 5), unlike most mines, many of the Viet Cong’s booby traps were made from bamboo – mine detectors couldn’t locate them. According to statistics compiled by the Australian Ministry of Defence (Australia had men in Vietnam for almost the entire conflict), 11% of all deaths and 15% of all wounds in Vietnam were due to booby traps (this is for all Allied troops, including U.S armed forces). Counting U.S forces alone, there were over 300,000 wounded in Vietnam. That means about 45,000 men were injured by booby traps. Photo Above: A booby trap with bamboo spikes – In the Cu Chi tunnels near the South Vietnam city of Saigon. Of these wounds, 2% came from punji stakes, the most infamous of all the booby traps employed by the Vietnamese during the war. Sharpened bamboo stakes of various length and width, punji stakes could be used in a variety of ways, most infamously in camouflaged pits. What’s worse, they were often coated in human or animal waste, making them biological weapons – the intent being to cause infection in the victim. Source reference details: https://www.warhistoryonline.com/vietnam-war/booby-traps-vietnam-war.html SOURCE M On Aug. 16, 1966, just days before the Battle of Long Tan, the 5th Battalion patrolled an area north of the Australian task force base. At the same time A Company of the 6th Battalion patrolled the area north and northeast. Intelligence reports estimated enemy strength as 300 to 3,500. Getting a fix on the enemy force was crucial because the Australian base camp at Nui Dat was in poor condition due to the monsoon weather and could be easily overrun. The rain made visibility practically nonexistent, and the ground turned into an oozing red mud that made maneuvering difficult. Source reference details: https://www.historynet.com/battle-of-long-tan-how-australians-and-new-zealanders-beat-odds/ SOURCE N New Zealand soldiers, all volunteers, signed up to go to war for a variety of reasons. These included overseas adventure (at the government’s expense!); a sense of duty and desire to stop the spread of communism; to test oneself in combat; and for the pay: “I was only getting $40 a week in New Zealand, and in Vietnam I was getting $130, which is why I went”, one veteran said. Over 200 men did a second ‘tour of duty’ to Vietnam and 40 did three. Many of the troops were Māori. Source reference details: Book by Historian Graeme Ball, Big World, Small Country: The 20th century and New Zealand’s place in it, published in 2013, page 330. SOURCE O

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)