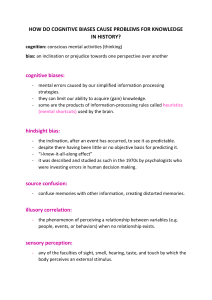

MODELS OF MEMORY Multi-Store Memory Model: A model is the visual representation of a theory, designed to explain the theory. Atkinson and Shiffrin’s (1968) multi-store memory model (MSM) is a model explaining their theory of memory. It explains how information flows through three stores, each having different capacities and durations: sensory memory, short-term memory (STM) and long-term memory (LTM). Model – visual representation of a theory, its purpose is to explain the theory. Sensory memory: is, as its name suggests, based on the five senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch, which are briefly retained memories of stimuli kept for just a fraction of a second. If we attend to this information (i.e. if we ‘notice’ it), then it is transferred to short-term memory. Short-term memory: lasts for about 30 seconds and is encoded phonetically and structurally (by sound and appearance of the words or items); and its duration can be increased by employing mnemonics (strategies to increase the capacity), by using pictures, or alphabetically or structurally organising the items in some way. Milner (1956) proposed the strategy of ‘chunking’ to extend the capacity of memory. We do this when we remember a phone number as a series of three or more chunks: 979 861 214, for example, rather than 979861214. If material is not processed (usually through rehearsal), then it is lost when new information comes into the shortterm memory store and displaces it. That information which is rehearsed in short-term memory is then transferred to long- term memory. Long-term memory: processes information semantically (by meaning) and the capacity is not known; it is thought by many psychologists to be unlimited. However, information in long-term memory can be hard to retrieve. Psychologists who have written since Atkinson and Shiffrin have identified separate types of long-term memory, which we will look at later. MSM MODEL: This is the most ‘famous’ model of memory, and its concepts are quite ‘commonly’ in everyday life. This model was created by Atkinson and Shiffrin in 1968. Its goal is to explain how memory flows through three ‘stores’ and each having different capacities and durations of time in which information can/will remain there: Sensory memory Short-term memory (STM) Long-term memory (LTM) Multi-store: There are 3 ‘stores’ which are theorized to exist in which memory functions. The difference between them is characterized by their capacity (to hold information) and duration (in which information can be held) SENSORY STORE: It is believed that we have a different sensory register for every sense: (seconds before it decays) Iconic memory (visual) Echoic memory (auditory) Gustatory (taste) Olfactory (smell) Tactile (touch) Attention is key to become short-term memory! SHORT-TERM STORE: Can hold 7 chunks of information at a time and lasts around 15-30 secs. This store has limited capacity, encodes info acoustically and must be rehearsed via repetition in order to remain in your memory. Milner (1956) proposed the strategy of ‘chunking’ to extend capacity of memory. LONG-TERM STORE: This store has a large capacity to hold information and can remain there for minutes or indefinitely. Encoding is mostly semantic but can be visual or acoustic. There are modern theories to suggest we have different types of long-term memory. Primacy effect: tendency to recall words at the beginning of a list when asked to remember it. Recency effect: the tendency to recall words at the end of a list when asked to remember it. MILNER HM: Anterograde amnesia – unable to make new memories. Hippocampus is needed to make long-term memories. Treatment for his epilepsy had been unsuccessful, so at the age of 27 HM (and his family) agreed to undergo a radical surgery that would remove a part of his brain called the hippocampus. AIM: To determine the extent of HM's memory deficiency. METHOD: An observational research method in which data is gathered for the same subjects repeatedly over a period of time; can extend over years or even decades. Neurosurgeon, Dr. Scoville, performed an experimental surgery taking out most of the hippocampus and tissue from the medial temporal lobes; HM was 27. Milner used many different strategies (like triangulation): - psychometric testing: IQ testing was given to HM - direct observation of his behavior - interviews with both HM and his family members - cognitive testing: memory recall tests and learning tasks (reverse mirror drawing) - MRI to determine extent of damage to the brain. RESULTS: Concluded that the hippocampus wasn't the site of memory storage, but the site where it turns short term to long term memories. He could remember something if he concentrated on it, but if he broke his concentration it was lost. After the surgery the family moved houses. They stayed on the same street, but a few blocks away. The family noticed that HM as incapable of remembering the new address, but could remember the old one perfectly well. He could also not find his way home alone. He could not find objects around the house, even if they never changed locations and he had used them recently. His mother had to always show him where the lawnmower was in the garage. He once ate lunch in front of Milner but 30 minutes later was unable to say what he had eaten, or remember even eating any lunch at all. When interviewed almost two years after the surgery in 1955, HM gave the date as 1953 and said his age was 27. He talked constantly about events from his childhood and could not remember details of his surgery. HM could not acquire new episodic knowledge (memory of events) and he could not acquire new semantic knowledge (general knowledge about the world). this suggests that the brain structures that were removed from his brain are important for long-term explicit memory. HM had a capacity for working memory since he was able to carry out a normal conversation. Memories in the form of motor skills (procedural memory) were well maintained. CONCLUSION: After an MRI scan of HM's brain was performed in 1992 and 2003 by Corkin, the extensive damage to the temporal lobe (including the hippocampus) explains the problem of transferring short-term memory to long-term memory as this is the area where the neurotransmitter acetylcholine is believed to play an important role in learning and the formation of explicit memories. LINK BACK: he had short term memory but he had problems in the transferring of memory from short-term to long-term due to not having a hippocampus. He could retrieve some memories and information from his past. This is just one example of biological evidence that STM and LTM are located in different stores in the brain. In Milner's study, HM had anterograde amnesia - that is, he could not transfer new information to long-term memory; however, he still had access to many of his memories prior to his surgery. However, the fact that he could create new procedural memories shows that memory may be more complex than the MSM predicts. WORKING MEMORY MODEL: Expands on the MSM and the over-simplistic representation of the MSM and the short term memory store Here, the STM is not a static store, rather that it is a complex information processor– ‘a multi-component, flexible system of STM’ called the Working Memory Working memory: is a system for temporarily storing/holding and managing the information required to carry out complex cognitive tasks such as learning, reasoning, and comprehension. Components: Central executive – controls attention and the slave system. Visuo-spatial scratchpad – 'the inner eye' storage for spatial & visual information. Inner scribe and cache. Phonological loop – 'the inner voice' Phonological store Articulatory control system - 'the inner voice' Episodic buffer: temporary storage system that integrates information from the LTM Episodic buffer was added to model in 2000: The episodic buffer is responsible for: Linking/binding together information from all other elements of working memory (Phonological loop and VSS) with information relating to time and order. So that things occur in a continuing sequence, like a story from a book or movie. Buffer- temporarily hold information So…. ‘episodic’ in the sense that it is capable of holding episodes (integrated chunks of information) KF SHALLICE AND WARRINGTON (1974): AIM: To investigate the relationship between STM and LTM when STM is impaired PROCEDURE: Shallice and Warrington (1974) studied KF, a man (28 years old) whose brain had been injured in a motorcycle accident. He fractured his parieto-occipital lobe which also led to epilepsy K.F. was asked to repeat numbers, letters, and word strings aloud through various experiments (in depth study on one person = case study). RESULTS: KF’s LTM functioned normally, but his STM was severely impaired. Instead of around 7 items, KF was only able to recall 1 or 2 items from a list. KF forgot letters and digits much faster when he received them auditorily than visually. The uneven pattern of deficits suggests that KF had more than one STM store, which is consistent with the WM model. CONCLUSION: KF's impairment was mainly for verbal information - his memory for visual information was largely unaffected. This shows that there are separate STM components for visual information (VSS) and verbal information (phonological loop). LINK BACK: K.F.’s STM was severely impaired in that its capacity was greatly reduced; later experiments showed that his LTM was intact. The difference between auditory and visual memory capacity suggests two separate stores for these modalities (see working memory model below); and the fact that K.F. had an intact LTM and an impaired STM contradicts the MSM theory that material in LTM has first been processed in the STM. However, it does support Atkinson and Shiffrin’s contention that there are separate memory stores for STM and LTM. SCHEMA THEORY Schemas – claim that our mind has mental frameworks that help organize information. Provides an organising framework that helps make sense of information. They are based on information provided by our life experiences/beliefs. These schemas help us to save our cognitive energy when processing the millions of pieces of information we encounter every day. Memories are reconstructed each time they are recalled Schema alters content so that it is consistent with previous experiences/beliefs We fill in gaps using schema Barlett – Rorschach test: Bartlett conducted research using the Rorschach test He asked participants to look at the images and then asked them to recall the figures by draw them He found that participants would assign labels and names for each shape and object they saw This label often shaped the representation of the object drawn afterwards He concluded that perception of the shape determined how it was remembered Bartlett (1932): The British psychologist Frederic Bartlett was teaching at Cambridge University during the First World War, at a time when memory had only just started to be considered a psychological rather than a philosophical subject. Herman Ebbinghaus dominated the field at that time. He had spent days at a time learning lists of nonsense words, testing himself to see precisely how many he could remember. But Bartlett developed a different approach to the study of memory. He discovered that when he asked people to repeat an unfamiliar story they had read, they changed it to fit their existing knowledge, and that it was this revised story they then remembered. Bartlett was the first psychologist to use the term ‘schema’ to describe this phenomenon of the reconstruction of memory. He viewed it as the organisation of previous reactions and experiences in order to understand and predict present and future experiences. While the original schemas arise from the senses biologically, they are soon used cognitively - not only to accommodate new experiences, but also to shape reactions to them. In his classic ‘War of the Ghosts’ study (see below), he shows how his British participants adapt what they hear to their British schemas that they have constructed through experience, distorting the story in the process. Schemas: Bartlett (1932): “the organisation of previous reactions and experiences in order to understand and predict present and future experiences. While the original schemas arise from the senses biologically, they are soon used cognitively - not only to accommodate new experiences, but also to shape reactions to them” Piaget (1952): “cohesive, repeatable action sequences possessing component actions that are tightly interconnected and governed by a core meaning” Assimilation is using an existing schema to deal with a new object or event – once a child understands that a dog is hairy or furry with 4 legs, then all dogs are understood to belong to the schema. Accommodation is changing an existing schema or developing a new schema when it cannot adequately explain a new object or event: on seeing a cat for the first time this child may think it is a dog, until she is told that dogs do not meow, they bark and look a little different; that this is a cat. The child then needs to modify the dog schema to include barking, as well as develop a cat schema for four-legged furry animals which meow. BARTLETT (1932): AIM: To investigate the effect of a culturally-specific schema on a culturally unfamiliar story. METHOD: Participants were students at the University of Cambridge, and the original study was carried out as part of a series of studies into the reproduction of folktales that was published in 1920. Some of the methodological details are taken from this publication. 1. Individual recall and reproduction of the story. Participants read the ‘War of the Ghosts’ Native American folk tale over twice to themselves at their own normal reading pace, and looked at any accompanying pictures for a period of four minutes. (It is not clear from Bartlett’s account whether this particular story had accompanying pictures or not). First recalls and reproductions were begun 15 minutes after the original study of the material. In cases where a participant gave repeated reproductions, no reference to the original or to their own earlier reproductions was allowed. 2. Serial reproduction. One participant read the tale, and after a set period of time reproduced it in writing. This reproduction is then read to a second person, who reproduces it after a set period of time and then reads it to a third person, and so on. This is like the children’s game of ‘Chinese Whispers’. RESULTS: In both types of reproduction, the story was subject to three processes of reconstruction: Omission of the irrelevant, unfamiliar and unpleasant: Material that seemed irrelevant to the story was quickly left out of it. Ghosts are meant to occupy a central position in ‘The War of the Ghosts’, but this was not apparent to the British readers who dropped this reference to ghosts almost immediately. Only that which seemed to be rationally connected to a coherent story was retained. Unfamiliar terms were also lost, though sometimes, if they were in the context of something more familiar, they were transformed. Unpleasant material was omitted. ‘His face became contorted’ was often left out of the accounts. Transformation of the material: Familiarisation of unfamiliar material: ‘canoes’ became ‘boats’ and ‘paddling’ became ‘rowing’ Rationalisation of the material. Once the mention of ghosts had been omitted then explaining the painless wound and the strange death becomes problematic. The participants managed this by stating that the wound was from an arrow and his spirit left his body when he died. Words such as ‘therefore’, ‘for’ and ‘because’ are inserted to make the story coherent. Transposition of details from one part of the story to another Reversal of the parts played by different persons: in the story, firstly one of the warriors says they must go home because the Indian has been hit. In later reproductions he himself begs to be taken home. First he declares his own conviction that he will live, but later this is changed to a warrior telling him that he will live. Movements of objects: the arrows in the canoe become transposed to the Indian being hit by an arrow. The use of the verbs ‘hit’ and ‘shot’ in the original probably contributed to this. The changes in the serial reproduction were greater than those in the individual recall and reproduction, but the processes of reconstruction remained the same. He called this process ‘conventionalisation’ (1920, p. 31). CONCLUSION: Bartlett concluded from his research that memory was an active reconstruction based on previous cultural schemas that were constructed from culturally specific experience, in this case of what a story was. It was not, as thinking current at the time believed, the accurate retrieval of static memory traces. As he wrote: ‘Remembering is not the re-excitation of innumerable fixed, lifeless and fragmentary traces..., [but] ...an imaginative reconstruction or construction, built out of the relation of our attitude towards a whole active mass of organised past reactions or experience’ (1932, p. 213). LINK BACK: This links back to the schema theory because every time the participants were asked to recall the story they would use their schema to fill in gaps of words that were unfamiliar or unknown to them, therefore changing the story to make sure it was consistent with their own experiences and beliefs. Because the story is a bit complicated. so they reconstructed the memory of the story in their brain and also altering content with their own experiences and beliefs such as changing the word of canoes. THINKING AND DECISION-MAKING “Thinking involves using information and doing something with it, for example, deciding something. Thinking is based on factors such as concepts, processes, and goals. Modern research into thinking and decision-making often refers to rational (controlled) and intuitive thinking (automatic).” Describe the Dual systems theory (Kahneman) System 1 and System 2 Thinking and decision-making are closely related: we do not make a decision without thinking about it, even if only for a split second. There are two theoretical areas of thinking and decision-making: normative and descriptive theory. Normative theory is concerned with how people should make decisions in a condition of uncertainty: it is concerned with identifying the rational choice. Descriptive theory of thinking and decision-making is concerned with describing what people do, and explaining this with reference to the predictions made by normative theory. Normative theory has been used extensively in philosophy and behavioural economics to explain rational decision-making. Examples used to explain thinking are formal logic, probability and utility theory. Descriptive theories are used in behavioural economics and psychology to explain how people actually behave. The two theories we will be discussing are both descriptive theories that attempt to explain how people engage in thinking and decision-making: Dual-Systems theory (Systems 1 and 2 thinking) Theory of reasoned action and planned behaviour DUAL-SYSTEMS THEORY: The dual-process reflects the existence of two separate but interacting systems of thinking and decision-making: System 1, which is automatic, holistic and intuitive thinking based on heuristics and System 2, which is analytical, logical and slower thinking. System 1 operates automatically and cannot be turned off at will, mistakes of intuitive thought are difficult to prevent. For example, we cannot stop ourselves from seeing an optical illusion, even when we know that it is such an illusion. The same is true of cognitive illusions, such as the different cognitive biases brought about through heuristics, which we will look at in the next section. System 2 operations are effortful, and require conscious thought: Kahneman refers to it as the ‘working mind’. It is the system that follows rules, compares objects on several attributes, and makes deliberate choices between options. System 2 has low processing capacity and this requires high effort and the exclusion of attention to other matters. This is not to say that all System 1 thinking is inaccurate, or is all based on heuristics that automatically result in bias. Kahneman points out that not all intuitive judgements are produced by heuristics; the accurate intuition of experts is better explained by the automaticity that comes with prolonged practice. (Driving a car along a familiar, empty road is one example of this.) ATLER & OPPENHEIMER, 2007: AIM: Investigate how font affects thinking. METHOD: 40 Princeton students completed the Cognitive Reflections Test (CRT). This test is made up of 3 questions, and measures whether people use fast thinking to answer the question (and get it wrong) or use slow thinking (and get it right). Half the students were given the CRT in an easy-to-read font, while the other half were given the CRT in a difficult-to-read font. RESULTS: Among students given the CRT in easy font, only 10% of participants answered all three questions correctly, while among the students given the CRT in difficult font, 65% of participants were fully correct. CONCLUSION: When a question is written in a difficult-to-read font, this causes participants to slow down, and engage in more deliberate, effortful System 2 thinking, resulting in answering the question correctly. On the other hand, when the question is written in an easy-to-read font, participants use quick, unconscious and automatic System 1 thinking to come up with the obvious (but incorrect) answer LINK BACK: participants who had easy to read font made the decision to give the wrong answer because they used system 1 as it's faster and it operates automatically, it was a rushed decision. However in the hard to read font, the participants took more time to read and understand the writing so it was a higher effort and attention. They used system 2 to make their decision. They made the decision slower but it was still correct in the majority. EXTRA TERMS: (can be different questions) Intuitive thinking – fast and automatic – system 1 Rational thinking – slow and controlled – system 2 RESEARCH AND ETHICS RESEARCH METHODS: Case study: Case studies are in-depth investigations of a single person, group, event or community. Typically data are gathered from a variety of sources and by using several different methods (e.g. observations & interviews). Research may also continue for an extended period of time so processes and developments can be studied as they happen. The case study method often involves simply observing what happens to, or reconstructing ‘the case history’ of a single participant or group of individuals. Case studies allow a researcher to investigate a topic in far more detail than might be possible if they were trying to deal with a large number of research participants (nomothetic approach) with the aim of ‘averaging’. Key words: In depth investigation Individual or small group of people Triangulation Qualitative data (mostly) but can be quantitative Longitudinal (extended period) HM: In Milner HM a case study was used because it's an in depth investigation of a single person to better understand his memory and data was gathered through variety of methods such as psychometric testing: IQ testing was given to HM, direct observation of his behavior, interviews with both HM and his family members, cognitive testing: memory recall tests and learning tasks (reverse mirror drawing) and MRI to determine extent of damage to the brain. This showed triangulation. Most of the data gathered was qualitative however some could be quantitative for psychometric testing. It was a longitudinal study where data was gathered on HM repeatedly over an extended period of time. ETHICS: Informed consent: The purpose of the research, expected duration, and procedures Their right to decline to participate and to withdraw from the research The foreseeable consequences of declining or withdrawing Any potential risks, discomfort, or adverse effects Any prospective research benefits Limits of confidentiality Incentives for participation Whom to contact for questions about the research and research participants' rights HM: HM gave consent before any of his memory was gone, so he wouldn't have remembered that he signed consent and any of the procedures going on. HM did not have the right to withdraw and wouldn't remember. Corkin the neuroscientist did the experiments like MRI while Milner did observations. Someone else gave the consent for HM because he couldn't give it himself. However they did keep his confidentiality. Vulnerable – cognitive impairments Corkin (neuroscientist) and MIT had permitted Molaison to sign his own consent forms beginning in 1980. 1992 Molaison had a court-appointed conservator, after his parents were incapacitated. This person made decisions about consent. Who also donated his brain to science after his death. RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORY Memory is not an exact copy of the experience. Reconstructive memory is a theory of elaborate memory recall, in which the act of remembering is influenced by various other cognitive processes. E.g. A schema that helps organize and interpret information. Memories are reconstructed each time they are recalled (from storage). Schema alters content so that it is consistent with previous experiences/beliefs. We fill in gaps using schema. When we encode and retrieve episodic memories, we are influenced by our perceptions, past knowledge and personal beliefs. Although we may feel as if we retrieve memories intact from our LTM, there is a lot of evidence that memory is an active process of reconstruction. As Bartlett (1932) showed, cultural schemas allow us to reconstruct remembered stories and events out of our own past experiences. What is more, although we may have shared those experiences with friends and family, it only takes the action of asking two siblings to remember the same event from their childhood to make us realise that we reconstruct them differently from each other. Each of us has a unique experience of an event and a personal way of recollecting it through our own schemas. This reconstructive nature of memory is important for our day-to-day living, but it is even more important when it comes to questions of eyewitness testimony. The California Innocence Project was formed in 1999, and was the first of Innocence Projects worldwide. One of the main issues on which their lawyers focus is that of eyewitness misidentification of suspects. In the last fifty years, many studies have been conducted into eyewitness testimony and the three factors that are most likely to affect it: high emotion, including weapon focus; the desire to ‘fill in the gaps’ in a relevant way, and post-event information that can distort memory. Post-event information: The classic Loftus and Palmer (1974) study into eyewitness testimony illustrates the reconstructive nature of memory. At the end of their journal article, Loftus and Palmer state: ‘(I)t is natural to conclude that the label, smash, causes a shift in the memory representation of the accident in the direction of being more similar to a representation suggested by the verbal label’ (p.588). This is very similar to schema theory, and it could be argued that ‘smashed’ suggests a ‘serious accident’ schema that then triggers the higher estimate of speed, and the suggestion of broken glass at the scene. However, it is worth noting that Loftus and Palmer’s study itself is not an investigation of schema theory. LOFTUS & PALMER: AIM: To investigate how information provided after an event had occurred influenced the memory of a witness for that event. In this case, the information given was a change in wording of a critical question. METHOD: Two laboratory experiments were used for two segments of the study, each adopting an independent measures design. The researchers used an opportunity sample of 45 college students from the University of Washington for the first experiment and 150 participants for the second. Experiment 1: Participants were shown seven 5-30 seconds film clips of traffic accidents. The clips were excerpts from safety films made for driver education. After each film they filled a questionnaire about what they had seen. They were also asked some questions about the accident. The critical question (IV) here was, ‘About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?’ (Bold italics added, not in original.) Different conditions were used, where the verb was changed to ‘smashed’, ‘collided’, bumped’, ‘hit’ and ‘contacted’. Participants had to estimate the speed in miles per hour. The films were shown in different orders in each condition. This experiment was conducted over one and half hours. Experiment 2: 150 participants were divided into three groups. All participants watched a one-minute film on a multiple-car accident. They then answered some questions about the film. The critical question was, ‘How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?’ (bold italics added, not in original). The verb was changed to ‘smashed’ in the comparison group. The control group was not asked to estimate the speed. The participants were asked to return a week later. They were not shown the film again but asked several questions about the accident in the film. The critical question was, ‘Did you see any broken glass?’ They had to answer in terms of ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The question was placed in a random position on each question paper. The video did not have any broken glass. RESULTS: Experiment 1 – When the critical question had the word ‘smashed’ or ‘collided’, speed estimates were higher than for the other words used. For ‘smashed’ it was 40.8 mph, for ‘collided’ 39.3mph, while for ‘contacted’ the estimate was 31.8 mph. Experiment 2 – The word ‘smashed’, which implies a more forceful impact, drew more than twice as many ‘yes’ responses as when the word ‘hit’ was used and as compared with the control group. CONCLUSION: Experiment 1 -The speed estimate was moderated by the verb used to describe the intensity of the crash. The greater the intensity conveyed by the word, the higher the speed estimate to match it. The researchers also suggested that the estimate could be the result of demand characteristics. Since the participants were unsure of the speed, they offered a figure that they thought would be most suited for the purpose of the study. Again, the choice of verb acted as cue to make the participant guess what range of speed the researcher might be looking for. Experiment 2 - The estimates of the presence of glass increased with the intensity of the verb used to describe the crash. General Conclusion: Leading questions can alter the memory of events and lead to distortions. One initial change in wording can have prolonged effects on memory. Loftus and Palmer offered the reconstructive hypothesis to explain the phenomenon: a person obtains two kinds of information about an event – the first is the information obtained from perceiving the event itself; the second is the information supplied or acquired after the event. If there is some difference between the two sources, integration of post-event information can lead to memory distortions. The experiments demonstrate how external cues, such as leading questions or a suggested line of thinking, made available after an event can affect our subsequent memory of that event. LINK BACK: the memory of the participants were reconstructed with the use of different words to describe the crash. Because we associate 'smashed' with fast and 'contacted' with slow/gentle, we fill the gaps in our memory by schema with the knowledge we have from the use of words. Therefore information is reconstructed when memory is recalled from their storage of the crash as we are influenced by our perceptions, past knowledge and personal beliefs. It was post-event information so that might have influenced their recalling as it was after the crash and distorted the memory. CONFIRMATION BIAS Wason: Wason was surprised that more than half of his subjects were unable to figure out the simple rule. He believed these people failed because they only tested examples of the numbers that conformed to their original hypothesis. The correct answer was any ascending numbers (e.g. not just going up in twos) Wason coined the term “confirmation bias” and continued to study this cognitive error throughout his career. Confirmation bias: is a cognitive bias in which a person finds information that supports what they believe, or interprets available evidence as supporting what they already feel to be true. Most people seek data that are compatible with their beliefs rather than trying to refute the beliefs that they hold. We all have the tendency to seek out information corresponding to our beliefs, perhaps by reading certain newspapers, having friends with the same beliefs as us or paying attention only to that which supports what we always ‘knew’. Contrary to what we are taught about trying to refute hypotheses, most people seek data that are likely to be compatible with the beliefs they currently hold. Wason (1960) demonstrated the confirmation bias in a simple test with British university students: he gave them the 3 ascending numbers 4-6-8 and asked them to guess the rule he had used to devise the series. (It was simply ‘any 3 ascending numbers’.) Before submitting their answers, students had to generate their own sets of 3 numbers, and ask if they conformed to the rule. Of course, they did, as any three numbers that were neither identical nor descending conformed, but this prevented them from isolating the rule. They were seeking evidence that confirmed what they thought, not evidence that refuted the rule, so it could be more easily identified. To the extent that the strategy of looking only for positive cases is motivated by a wish to find confirmatory evidence, it is misguided. An attempt to refute the hypothesis would have given more clues to its true identity. (This has similarities to Wason’s ‘card test’ described earlier in this chapter, where participants consistently used heuristics to choose cards that confirmed the hypothesis rather than looking for refutation.) Hernandez & Preston (2013) found an unusual way to reduce confirmation bias, by making it harder to only focus on and read evidence that supports your own beliefs and expectations. They examined whether processing difficulty could potentially lead to less biased verdicts in a mock trial. HERNANDEZ & PRESTON: AIM: To investigate how disfluency affects the confirmation bias in decision-making. METHOD: A lab experiment, using 408 participants (144 women, 259 men, and 5 no response to the gender question) who completed a brief questionnaire on Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk survey website. After no responses and double responses were removed, the final volunteer sample was 398. All participants were told that they would read information about a defendant and would be asked to reach a verdict. Participants were randomly assigned to either a positive or negative bias condition, and then assigned randomly again to one of four conditions (8 groups in all): Fluent crime description Disfluent crime description Disfluent + Time constraint – given a timer and told to submit their responses as soon as the timer reached 3 minutes. Disfluent + Memory load – shown a list of 9 words of objects unrelated to the case and asked to keep them in mind throughout for later recall. (These last two conditions were combined as a ‘cognitive load’ condition once there was seen to be no significant effect of each separately.) Next they read a witness testimony from the defendant’s school psychologist about her interactions with the defendant, Donald. This was skewed either positively or negatively. They then read a description of the objective facts of the case: Donald was accused of a robbery, but his guilt is ambiguous. In the fluent condition, the facts were written in a Times New Roman 16-point font. In the disfluent condition, the text was in a 12-point Times New Roman font that had been photocopied poorly until the writing was legible but not easy to read. After reading the appropriate document, participants declared their verdict of guilty/not guilty and their sentence of 0 to 5+ months. They were also asked to rank their certainty on a 7-point scale, from 1 = extremely certain he is not guilty to 7 = extremely certain he is guilty, and their interest in the study, from 1= extremely bored to 7 = extremely interested. RESULTS: There was a significant effect of bias on the verdict, with more guilty verdicts in the negative bias condition, but no significant difference in effect between the time constraint and memory load conditions, so they were combined into a single ‘cognitive load’ condition for the other analyses. Confirmation bias effects were observed, but only in the fluent and cognitive load conditions: participants who read the fluent information were more lenient when they were in the positive bias condition, and participants who were in the cognitive load condition also showed a positive/negative confirmation bias, depending on their condition. That is, those in the positive disfluent + cognitive load condition showed a positive confirmation bias and those in the negative disfluent + cognitive load condition showed a negative confirmation bias. Moreover, participants with confirmation bias were also more certain of their decision. The % of participants who found Donald guilty when reading the text under the disfluent condition was 58% for the positive bias and 60% for the negative bias. This shows clearly how disfluency interrupted the effect of cognitive bias. There were no significant effects of bias or condition on interest in the study. CONCLUSION: These results show that confirmation bias took place when information was presented fluently, but not when it was presented disfluently. The fact that confirmation bias also occurred when participants read disfluent information under cognitive load of time pressure or memory load, shows that cognitive resources are necessary to overcome confirmation bias. The difficulty associated with disfluency encourages a slower and more careful mindset when making judgements, even when coming to an issue with existing biases, and the pressure of cognitive load makes the confirmation bias more likely. LINK BACK: People in the positive bias group were looking at the facts from a positive lens as the evidence supported what they felt already, therefore they had positive confirmation bias. Compared to the negative bias group where the negative facts impacted how they felt about the verdict, therefore they found the defendant guilty and had negative confirmation bias. EXPLAIN ONE BIAS IN THINKING AND DECISION MAKING (9) Intro: Wason, definitions, description of the bias One study that investigates confirmation bias is…..HP LB: How does the bias impact thinking AND decision making? RESEARCH AND ETHICS RESEARCH: Describe the lab experiment method in detail using these terms: Control over extraneous variables IV and DV = cause and effect Random allocation to groups Standardization Loftus & Palmer: IV – question with the adjective describing the crash changing each time: ‘smashed’, ‘collided’, bumped’, ‘hit’ and ‘contacted’ DV – speed estimates for cars Participants are randomly allocated into groups. Every participant watched the same video 7 times and the method was standardized. ETHICS: Protection of participants – Researchers must ensure that those taking part in research will not be caused distress. They must be protected from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend or harm participants. Normally, the risk of harm must be no greater than in ordinary life, i.e. participants should not be exposed to risks greater than or additional to those encountered in their normal lifestyles. The researcher must also ensure that if vulnerable groups are to be used (elderly, disabled, children, etc.), they must receive special care. For example, if studying children, make sure their participation is brief as they get tired easily and have a limited attention span. Researchers are not always accurately able to predict the risks of taking part in a study and in some cases, a therapeutic debriefing may be necessary if participants have become disturbed during the research. Hernandez & Preston: Disfluent + Time constraint group were given a timer and told to submit their responses as soon as the timer reached 3 minutes. This could’ve caused stress on them EMOTION AND COGNITION The research by Loftus et al. (1987) into weapon focus, described in the previous section, can be used as a good example of how emotion affects memory by a narrowing of perception that concentrates attention on a weapon and means that the person forgets peripheral details. One classic piece of research which claims that emotional memories are more accurate and vivid than other memories is that of Brown and Kulik (1977). Their theory of ‘flashbulb memories’ has been applied by subsequent researchers and critiqued by many. Flashbulb memories are memories for the circumstances in which one first learned of a surprising and emotionally arousing event. Flashbulb memory – highly detailed, exceptionally vivid 'snapshot' of the moment and circumstances in which a piece of suprising and consequential (or emotionally arousing) news was heard. Are one type of autobiographical memory. Eg: stored on one occasion and retained for a lifetime. These memories are associated with important historical or autobiographical events. Role of amygdala in memory: The amygdala – a pair of small almond-shaped regions deep in the brain, help regulate emotion and encode memories—especially when it comes to more emotional remembrances. Amygdala activation enhances memory consolidation by facilitating neural plasticity and information storage processes. Enables us to acquire and retain lasting memories of emotional experiences. The amygdala may be best known as the part of the brain that drives the socalled “fight or flight” response. While it is often associated with the body’s fear and stress responses, it also plays a pivotal role in memory. “If you have an emotional experience, the amygdala seems to tag that memory in such a way so that it is better remembered.” Encoding and better vivid recall is possible Emotion most linked to flashbulb memory is suprise because it's unexpected and can boost adrenaline BROWN & KULIK: AIM: To investigate whether suprising and personally significant events can cause flashbulb memories. METHOD: The researchers asked 40 black and 40 white American male participants to fill out a questionnaire regarding the death of public figures – such as president John F Kennedy and Martin Luther Jr – as well as of someone they personally knew. They were asked a series of questions about the event including: Where were you when you heard about the event? How did you feel when you heard about the event? (to indicate level of emotion) How important was this event in your life? (to indicate personal experience) How often have you talked about this event? (to indicate rehearsal). In the event that they did not recall the circumstances under which they heard of the event (death of the political leader, or the personal event), the participant just answered ‘No’ and moved onto the next question. If they answered ‘Yes’, they were then invited to write a free recall of the circumstances in any form or order and at any length. They were also asked to rate the personal importance of the event to themselves. RESULTS: The categories of circumstances that appeared most often in people’s memories were: Place, Ongoing Activity, Informant, Own Affect (Emotions), Other Affect (Emotions of Others), and Aftermath. (Note: a flashbulb memory is not memory of the actual event but for the circumstances in which one first heard the news.) 39/40 of the white European Americans and 40/40 of the black African Americans reported flashbulb memories for Kennedy’s assassination and 69/80 participants reported a flashbulb memory for a personal shock. Flashbulb memories, but in lower numbers, were recorded for nearly all of the other famous leaders, with the African Americans having more flashbulb memories for the Civil Rights leaders Martin Luther King and Medgar Evans and the black Muslim leader Malcolm X and the European Americans having more for Gerald Ford and Robert Kennedy. Consequentiality (personal significance) of the leader was correlated with flashbulb memory for the circumstances in which a participant heard of his death. Participants remembered where they were, what they were doing and how they felt when learning about shocking public events Researchers found that the 1963 John F. Kennedy assassination led to the most flashbulb memories (90% of people remembered this in context with vivid detail) African Americans also recalled more FM of civil rights leaders (ex. The assassination of Martin Luther King) more than Caucasian participants For the self-selected events, most participants had FM of deaths of family (ex. parents) CONCLUSION: Flashbulb memory is the term for the instant and vivid recording by a neurobiological mechanism of the circumstances surrounding a person being informed of a personally significant and surprising event. The two main factors of importance are a high level of surprise and a high level of personal significance, which combine to create a high level of emotional arousal and a flashbulb memory. LINK BACK: the reason why they could recall is due to the surprise linked to the memory of the circumstances around the event, which supports the theory that the amygdala plays a role in the consolidation of memory as the emotion of surprise is why they could recall the circumstances so vividly. RESEARCH METHODS: Questionnaire: A questionnaire is a research instrument consisting of a series of questions for the purpose of gathering information from respondents. Questionnaires can be thought of as a kind of written interview. They can be carried out face to face, by telephone, computer or post. Questionnaires provide a relatively cheap, quick and efficient way of obtaining large amounts of information from a large sample of people. However, a problem with questionnaires is that respondents may lie due to social desirability. Most people want to present a positive image of themselves and so may lie or bend the truth to look good, e.g., pupils would exaggerate revision duration. There were open and closed questions, so they had qualitative and quantitative data. Brown & Kulik: written interview about their memory, experiences and emotions. Questions were standardized, same for everyone. ETHICS: Protection of participants – Researchers must ensure that those taking part in research will not be caused distress. They must be protected from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend or harm participants. Normally, the risk of harm must be no greater than in ordinary life, i.e. participants should not be exposed to risks greater than or additional to those encountered in their normal lifestyles. The researcher must also ensure that if vulnerable groups are to be used (elderly, disabled, children, etc.), they must receive special care. For example, if studying children, make sure their participation is brief as they get tired easily and have a limited attention span. Researchers are not always accurately able to predict the risks of taking part in a study and in some cases, a therapeutic debriefing may be necessary if participants have become disturbed during the research. Brown & Kulik: "tenth question asled about a personal, unexpected shock, such as the death of a friend or relative, serious accident, diagnosis of a deadly disease" Emotion (suprise, sadness etc. From hearing about the death of a loved one) Distress Potential psychological harm Debrief needed