Kant - Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime and Other Writings

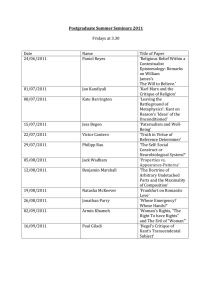

advertisement