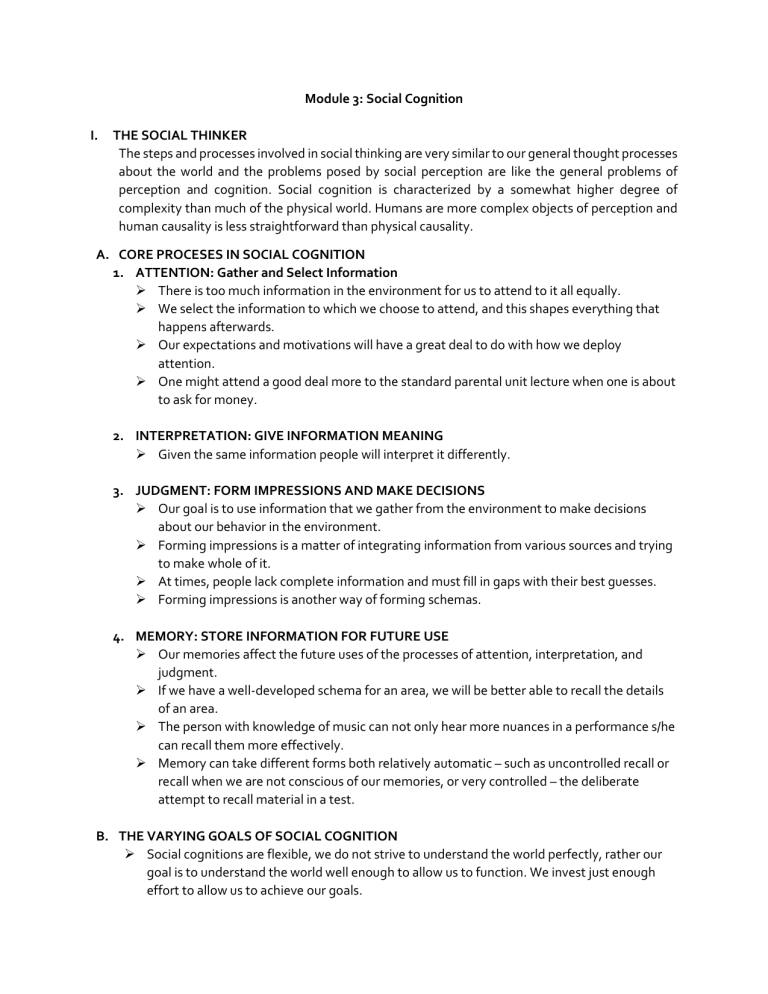

Module 3: Social Cognition I. THE SOCIAL THINKER The steps and processes involved in social thinking are very similar to our general thought processes about the world and the problems posed by social perception are like the general problems of perception and cognition. Social cognition is characterized by a somewhat higher degree of complexity than much of the physical world. Humans are more complex objects of perception and human causality is less straightforward than physical causality. A. CORE PROCESES IN SOCIAL COGNITION 1. ATTENTION: Gather and Select Information ➢ There is too much information in the environment for us to attend to it all equally. ➢ We select the information to which we choose to attend, and this shapes everything that happens afterwards. ➢ Our expectations and motivations will have a great deal to do with how we deploy attention. ➢ One might attend a good deal more to the standard parental unit lecture when one is about to ask for money. 2. INTERPRETATION: GIVE INFORMATION MEANING ➢ Given the same information people will interpret it differently. 3. JUDGMENT: FORM IMPRESSIONS AND MAKE DECISIONS ➢ Our goal is to use information that we gather from the environment to make decisions about our behavior in the environment. ➢ Forming impressions is a matter of integrating information from various sources and trying to make whole of it. ➢ At times, people lack complete information and must fill in gaps with their best guesses. ➢ Forming impressions is another way of forming schemas. 4. MEMORY: STORE INFORMATION FOR FUTURE USE ➢ Our memories affect the future uses of the processes of attention, interpretation, and judgment. ➢ If we have a well-developed schema for an area, we will be better able to recall the details of an area. ➢ The person with knowledge of music can not only hear more nuances in a performance s/he can recall them more effectively. ➢ Memory can take different forms both relatively automatic – such as uncontrolled recall or recall when we are not conscious of our memories, or very controlled – the deliberate attempt to recall material in a test. B. THE VARYING GOALS OF SOCIAL COGNITION ➢ Social cognitions are flexible, we do not strive to understand the world perfectly, rather our goal is to understand the world well enough to allow us to function. We invest just enough effort to allow us to achieve our goals. 1. CONSERVE MENTAL EFFORT ➢ The social environment is amazingly complex, and humans have only a limited attentional capacity. As a result, people often use simplifying strategies that require few cognitive resources and that provide judgments that are generally "good enough." ➢ However, keep in mind that most of the time the decisions made are adequate. ➢ EXPECTATION CONFIRMATION STRATEGIES o Often this conservation of mental effort takes the form of trying to support preexisting expectations and the entire process of information gathering and processing becomes an exercise in “don’t bother me with the facts, my mind is already made up”. a. CONSERVATISM ➢ Individuals’ and groups’ views of the world are slow to change and prone to perpetuate themselves. ➢ We will hunt for and accept data that confirm those conceptions that we already have— we are going to consider this in more depth in a moment with expectation confirmation strategies and self–fulfilling prophecies. b. ACCESSIBILITY ➢ People generally prefer to use the information that is most ready to hand. ➢ Thus, we often overestimate the importance or frequency of event because they are easily noticed or recalled. c. SUPERFICIALITY VS. DEPTH ➢ Much of the time, people seem to operate on automatic, putting little effort into forming a superficial picture of reality and relying heavily on whatever information is most accessible. But sometimes people take the time and trouble to process information more extensively. ➢ This occurs particularly when they notice that reality fails to match their expectations, or when important goals are threatened. 2. MANAGE SELF-IMAGE ➢ We want to think well of ourselves, and we want others to think well of us. ➢ Consider how much of our self–concept depends on the behaviors of others in the form of reflected appraisal, or comparison with others in social comparison. ➢ This may involve perceptions of oneself or perceptions of others that have implications for oneself. 3. GAIN ACCURATE INFORMATION ➢ When people have a special desire to have control over their lives, or when they want to avoid making mistakes, they sometimes put aside their simplifying and self-enhancing strategies in the hope of gaining more accurate understanding of themselves and others. ➢ People strive for mastery. We seek to understand and predict events in the social world we inhabit to obtain many types of rewards. The only way to do this is to have accurate information about the world, or at least good enough information. II. PEOPLE AS EVERYDAY THEORISTS: SCHEMAS & THEIR INFLUENCE ➢ A SCHEMA is a cognitive framework or concept that helps organize and interpret information. They allow people to take shortcuts in interpreting the vast amount of information that is available in the environment. ➢ Schemas act as filters, screening out information that is inconsistent with them. In addition, human memory is reconstructive, adding information to what is experienced. ➢ These reconstructions are schema-consistent, further reinforcing them. These processes combine to make schemas very resistant to change. ➢ Schemas are generalized mental representations that organize knowledge and guide information processing. For example, one’s schema for mice might include the expectation that they are small, and furry, and eat cheese. ➢ Schemas may cause some people to exclude pertinent information to focus instead only on things that confirm his pre-existing beliefs and ideas. ➢ Schematic expectations may lead us to see something that is not there. One experiment found that people are more likely to perceive a weapon in the hands of a black man than a white man (Correll et al., 2002). o STEREOTYPES: ▪ A generalized set of beliefs about a particular group of people. ▪ Stereotypes are often related to negative or preferential attitudes (prejudice) and behavior (discrimination). ▪ Schemas can contribute to stereotypes and make it difficult to retain new information that does not conform to our established ideas about the world. o SCRIPTS ▪ Schemas for types of events ▪ EXAMPLE: Doing the laundry, going to McDonalds. A. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF SCHEMAS ➢ FREDERIC BARTLETT o Used schema as a basic concept as part of his learning theory. o His theory suggested that our understanding of the world is formed by a network of abstract mental structures. ➢ JEAN PIAGET o According to his theory of cognitive development, children go through a series of stages of intellectual growth. o In Piaget’s theory, a schema is both the category of knowledge as well as the process of acquiring that knowledge. o He believed that people are constantly adapting to the environment as they take in new information and learn new things. B. TYPES OF SCHEMAS ➢ While Piaget focused on childhood development, schemas are something that all people possess and continue to form and change throughout life. 1. OBJECT SCHEMAS ➢ Just one type of schema that focuses on what an inanimate object is and how it works. ➢ Help us understand and interpret inanimate objects, including what different objects are and how they work. ➢ FOR EXAMPLE: o Most people in industrialized nations have a schema for what a car is. o Your overall schema for a car might include subcategories for different types of automobiles such as a compact car, sedan, or sports car. 2. PERSON SCHEMAS ➢ Focused on specific individuals. ➢ Created to help us understand specific people. ➢ FOR EXAMPLE: o Your schema for your friend might include information about her appearance, her behaviors, her personality, and her preferences. o One’s schema for their significant other will include the way the individual looks, the way they act, what they like and do not like, and their personality traits. 3. SOCIAL SCHEMAS ➢ Include general knowledge about how people behave in certain social situations. ➢ A cognitive structure of organized information, or representations, about social norms and collective patterns of behavior within society. ➢ Often underlie behavior of the person acting within group contexts – particularly larger group or societal contexts. ➢ Helps us understand how to behave in different situations. ➢ FOR EXAMPLE: o If an individual plants to see a movie, their movie schema provides them with a general understanding of the type of social situation to expect when they go to the movie theater. 4. SELF-SCHEMAS ➢ Focused on one’s knowledge about the self. ➢ This can include both what one knows about his current self as well as his ideas about his idealized or future self. ➢ They focus on what we know about who we are now, who we were in the past, and who we could be in the future. 5. EVENT SCHEMAS (SCRIPTS) ➢ Focused on patterns of behavior that should be followed for certain events. ➢ This acts much like a script informing you of what you should do, how you should act, and what you should say in a particular situation. ➢ Encompass the sequence of actions and behaviors one expects during a given event. ➢ FOR EXAMPLE: o When an individual goes to see a movie, they anticipate going to the theater, buying their ticket, selecting a seat, silencing their mobile phone, watching the movie, and then exiting the theater. 6. ROLE SCHEMAS ➢ Encompass our expectations of how a person in a specific social role will behave. ➢ FOR EXAMPLE: o We expect a waiter to be warm and welcoming while not all waiters will act that way, our schema sets our expectations of each waiter we interact with. C. HOW SCHEMAS CHANGE ➢ Jean Piaget suggested that people grow intellectually by adjusting their schemas when new information comes from the external world. ➢ Schemas tend to be easier to change during childhood but can become increasingly rigid and difficult to modify as people grow older. ➢ Schemas will often persist even when people are presented with evidence that contradicts their beliefs. ➢ In many cases, people will only begin to slowly change their schemas when inundated with a continual barrage of evidence pointing to the need to modify it. a. ASSIMILATION ➢ New information is incorporated into pre-existing schemas. ➢ The process of applying the schemas we already possess to understand something new. b. ACCOMMODATION ➢ The process of changing an existing schema or creating a new one because new information does not fit the schemas one already has. ➢ Existing schemas might be altered, or new schemas might be formed as a person learns new information and has new experiences. D. HOW SCHEMAS AFFECT LEARNING ➢ Schemas play a role in the learning process. 1. SCHEMAS INFLUENCE WHAT WE PAY ATTENTION TO. ➢ People are more likely to pay attention to things that fit in with their current schemas. 2. SCHEMAS IMPACT HOW QUICKLY PEOPLE LEARN. ➢ People learn information more readily when it fits in with the existing schemas. 3. SCHEMAS HELP SIMPLIFY THE WORLD. ➢ Schemas can often make it easier for people to learn about the world around them. ➢ New information could be classified and categorized by comparing new experiences to existing schemas. 4. SCHEMAS ALLOW US TO THINK QUICKLY. ➢ Even under conditions when things are rapidly changing our new information is coming in quickly, people do not usually have to spend a great deal of time interpreting it. ➢ Because of existing schemas, people are able to assimilate this new information quickly and automatically. 5. SCHEMAS CAN CHANGE HOW WE INTERPRET INCOMING INFORMATION. ➢ When learning new information that does not fit with existing schemas, people sometimes distort or alter the new information to make it fit with what they already know. 6. SCHEMAS CAN BE REMARKABLY DIFFICULT TO CHANGE. ➢ People often cling to their existing schemas even in the face of contradictory information. E. HOW OUR SCHEMAS GET US INTO TROUBLE ➢ The study by Brewer & Treyens (1981) demonstrates that people notice and remember things that fit into their schemas but overlook and forget things that do not. In addition, when people recall a memory that activates a certain schema, they may adjust that memory to better fit that schema. ➢ Schemas can lead to PREJUDICE. o Some of our schemas will be stereotypes, generalized ideas about whole groups of people. Whenever we encounter an individual from a certain group that we have a stereotype about, we will expect their behavior to fit into our schema. This can cause us to misinterpret the actions and intentions of others. ➢ FOR EXAMPLE: o We may believe anyone who is elderly is mentally compromised. If we meet an older individual who is sharp and perceptive and engage in an intellectually stimulating conversation with them, that would, challenge our stereotype. However, instead of changing our schema, we might simply believe that the individual was having a good day. Or we might recall the one time during our conversation that the individual seemed to have trouble remembering a fact and forget about the rest of the discussion when they were able to recall information perfectly. Our dependence on our schemas to simplify our interactions with the world may cause us to maintain incorrect and damaging stereotypes. REFERENCES: American Psychological Association (2020). Social schema. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/social-schema. Boundless Psychology (2020). Social cognition. Lumen Learning. Retrieved https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-psychology/chapter/social-cognition/. from Cherry, K. (2019). The role of a schema in psychology. VeryWell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-schema-2795873. Vinney, C. (2019). What is a schema in psychology? Definition and examples. ThoughtCo. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/schema-definition-4691768.