Functional and Practical Aspects of Non-Finite Forms of the Verb in English

advertisement

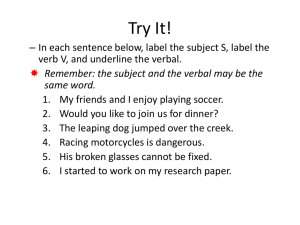

THE MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND EDUCATION OF UKRAINE KYIV NATIONAL LINGUISTIC UNIVERSITY COURSE PAPER “Functional and practical aspects of non-finite forms of the verb in English” Nadiya Gorkawa group 405 research advisor: Cand. of Linguistics, Associate Prof. L.M.Volkova KYIV - 2008 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..……………………………………………………………..3 СHAPTER I. Non-finite forms of the verb from the perspectibe of thier functional characteristics…………………………………..…………………...5 I.1. The development of non finite forms of the verb ………..………………5 I.2. The functional aspect of verbals…………………………………………...…7 I.2.1. The infinitine……………………………………………………...…...7 I.2.2. The gerund………………………………………................................13 I.2.3. The participle…………………………………………………………18 CHAPTER II. Controversy in the usage of non-finite forms of the verb………………….…………………………………………………………..23 II.1. The gerund and the infinitive……………………………………………... 23 II.2. Participle I and the gerund……..…………………………………………. .26 II.3. Nominative phrases and gerundial constructions……………………..........29 CONCLUSIONS…………………………………………………………….....31 RESUME………………………………………………………………………..32 REFERENCE LITERATURE...…….………………………………………...33 2 INTRODUCTION The words of every language fall into classes which are called Parts of Speech. Each part of speech has characteristics of its own. The parts of speech differ from each other in meaning, in form and in function. Verb is unconditionally one of the essential parts of speech not only in English, but in any human language. Actually, without a verb the “simple” process of representation of ones thought through the language would be practically impossible. The complicated structure and character of the verb has given rise to much dispute and controversy. The morphological field of the English verb is heterogeneous. It includes a number of groups or classes of verbs, which differ from each other in their morphological and syntactic properties. Thus, all English verbs have finite and non-finite forms (these forms are also called the verbals or sometimes verbids1). All finite verbs without exception can perform the function of the verbpredicate, while non-finite verbs perform different functions according to their intervening nature. The non-finite forms of the verb are more simple and economical expressive means of thought and may be used as any member of the sentence except the predicate. Verbals are not used separately and make up complexes with other members of the sentence. The non-finite forms unlike the finite forms of the verbs do not express person, number or mood. Therefore they cannot be used as the predicate of a sentence. Like the finite forms of the verbs verbals have tense and voice distinctions, but their tense distinctions differ from those of the finite verb. The forms that are called tenses in the verbals comprise relative time indication; they usually indicate whether the action expressed by the verbal coincides with the action of the finite forms of the verb or is prior to the action of the finite forms of the verb. Thus, they can be combined with verbs like non-processual lexemes 1 Блох М.Я. Теоретическая грамматика английского языка. – 3-е изд., испр. – М.: Высшая школа, 2000. – 381 с. (на англ. яз.) 3 (performing non-verbal function in the sentence), and the can be combined with non-processual lexemes like verbs (performing verbal functions in the sentence)2. As a result, the implement of the verbals to the great class of verbs was not once open to question. Some scholars claimed that such a difference in features may be considered a sufficient ground for separation of a new part of speech. Yet now these suggestions still remain minor in the linguistic societies and verbals are considered as the plenipotentiary subcass of the verb. Thereby, the aim of this course paper is to study the variety of verbals according to their functional distribution and practical usage and interchangability from the point of their similarity in form and functions. This paper is concentrated on such questions as what functions the verbals do perform in the sentence, how they correlate with each other, and what does the practical usage of the non-finite forms of the verb implies. Thus, the object of the research is the English texts which contain nonfinite forms of the verb. The subject of the research is the functional and practical distribution of verbals. There are three verbals in English: the participle, the gerund, and the infinitive. Speaking of the Ukrainian language, there are also three non-finite forms of the verb, but they do not fully coincide with those in the English language (дієприкметник, дієприслівник, інфінітив). The verbals combine the characteristics of a verb with those of some other part of speech. Thus the infinitive and the gerund have besides verb characteristics also traits in common with the noun. The participle has the characteristics of both verb and adjective and in some of its functions it combines the characteristics of a verb with those of an adverb. 2 Блох М.Я. Теоретическая грамматика английского языка. – 3-е изд., испр. – М.: Высшая школа, 2000. – 381 с. (на англ. яз.) 4 СHAPTER I. Non-finite forms of the verb from the perspectibe of thier functional characteristics I.1 From the history of non-finite forms of the verb In Old English period only the infinitive and the participle were distinguished. In many respects they were closer to the nouns and adjectives than to the finite verb. Their nominal features were more obvious than their verbal features, especially at the morphological level. The verbal nature of the infinitive and the participle was revealed in some of their functions and in their ability to take direct objects and be modified by adverbs. The infinitive had no verbal grammatical categories. Being a verbal noun by origin, it had a sort of reduced case-system: two forms which roughly corresponded to the Nom. and the Dat. cases of nouns — beran — uninflected infinitive ("Nom." case) to berenne or to beranne — inflected infinitive ("Dat." case). Like the Dat. case of nouns the inflected infinitive with the preposition to could be used to indicate the direction or purpose of an action, e.g.: paet weorc is swipe pleolic me... to underbeoinenne 'that work is very difficult for me to undertake'. The uninflected infinitive was used in verb phrases with modal verbs or other verbs of incomplete predication, e. g.: hie woldon hine forbsernan 'they wanted to burn him' pu meaht singan 'you can sing' (lit. "thou may sing") pa onson he sona singan 'then began he soon to sing'. The participle was a kind of verbal adjective which was characterized not only by nominal but also by certain verbal features. Pa rticiple I was opposed to participle II through voice and tense distinctions: it was active and expressed present or simultaneous processes and qualities, while participle II expressed states and qualities resulting from past action and was contrasted to participle I as passive to active, if the verb was transitive. Participle II of intransitive verbs had an active 5 meaning; it indicated a past action and was opposed to Participle I only through tense. Participles were employed predicatively and attributively like adjectives and shared their grammatical categories: they were declined as weak and strong and agreed with nouns in number, gender and case. The distinctions between the two participles preserved in Middle English and New Englihs: participle I had an active meaning and expressed a prior quality simultaneous the events described by predicate of the sentence. Participle II had an active or passive meaning depending on the transitivity of the verb and expressed a preceding tion or its results in the subsequent situation. Following the main trends of the evolution of the verbals in ME and NE the gradual loss of most nominal features (except syntactical functions) and growth of verbal features should be noted. The simplifying changes in the verb paradigm, and the decay of the OE inflectional system account for the first of these trends — loss of case distinctions in the infinitive and of forms of agreement in the participles. The preposition to, which was placed in OE before the inflected infinitive to show direction or purpose, lost its prepositional force and changed into a formal sign of the infinitive. From the XIIth. cent the earliest instances of a verbal noun the gerund can be found. It is used in substantival function with a prepositional object like a verbal noun and with a direct object. In Early NE the -ingform in the function of the noun is commonly used with an adverbial modifier and with a direct object — in case of transitive verbs, e.g.: Tis pity ... That wishing well had not a body in't Which might be felt. (Shakespeare) The nominal features retained from the verbal noun, were its syntactic functions and the ability to be modified by a possessive pronoun or a noun in the Gen. case: And why should we proclaim it in an hour before his enteri (Shakespeare. 6 Indeed, in the course of time the sphere of the usage of the gerund extended to replace the infinitive and the participle in many adverbial functions. Its major advantage was that it could be used with various prepositions: And now he fainted and cried, in fainting, upon Rosalind. Thus, the syntactic functions of the verbal noun, the infinitive and the participle partly overlapped. While the verbals lost their nominal grammatical categories, they retained their nominal syntactic features: the syntactic functions corresponding to those of the noun and adjectives; they also retained their verbal syntactic features — the ability to take an object and an adverbial modifier. I.2. The functional aspect of verbal I.2.1. The infinitive An infinitive is a verbal consisting of the partice to plus a verb (in its simplest "stem" form) and functioning as a noun, adjective, or adverb. The term verbal indicates that an infinitive, like the other two kinds of verbals, is based on a verb and therefore expresses action or a state of being. Although an infinitive is easy to locate because of the pattern to + verb form, deciding what function it has in a sentence can sometimes be confusing. It should not be confused with a prepositional phrase beginning with to, which consists of to plus a noun or pronoun and any modifiers. Although the infinitive was originally a verbal noun, in the course of its development it has acquired some characteristics of the verb and is at present intermediate between verb and noun. Such mixture of featurer plays an important role in definind the functions of the infinitive. Among verbal characteristics of the infinitive such shoud be mentioned: • First of all, it has tense, aspect and voice distinctions, according to which the following forms are distinguished: 7 Indefinite Infinitive Active is the only simple form of the infinitive. It expresses the simultaneous action to the one expressed by the finite verb that is why it may refer to any of three times – present, past or future. Other forms are more complex and are formed with the help of auxiliary verbs to be or to have and participle: He helped me to carry the heavy box. When combined with modal verbs and their equivalents, the indefinite infinitive may also refer to a future action: It may ram to-morrow. I have to go there next week. Continuous Infinitive Active is formed with the help of auxiliary verb to be and participle I, and expresses the progressive action simultaneous to the action expressed by the finite verb. Perfect Infinitive Active in its turn is formed with the auxiliary verb to have and participle II, and expresses the action prior to the action expressed by the finite verb: I am sorry not to have been present at the meeting. In case the perfect infinitive is associated with a modal verb the infinitive, it can indicate either that the action took place in the past and the infinitive is equivalent to a past: Why did she go away so early last night? She may have been ill (perhaps she was ill); or the infinitive indicates that the action is already accomplished at a given moment and is viewed from that moment and it has the meaning of a perfect: Why doesn't she come? She may not have arrived yet (perhaps she has not yet arrived). After the modal verbs should, could, ought (subjunctive II) and the past indicative of the verb to be the perfect infinitive is used to show that the action was not carried out: You should have done it yesterday (but you did not). He ought to have consulted a doctor (but he did not). Perfect Continuous Infinitive Active is formed with the help of auxiliary verb to be in the form of perfect infinitive (to have been) and participle I, and denotes the action that was in progress for some time before the action expressed by the finite verb. 8 Indefinite Infinitive Passive is formed with the help of auxiliary verb to be and Participle II. Perfect Infinitive Passive is formed with the help of auxiliary verb to be in the form of Perfect Infinitive (to have been) and participle II. • In common with the finite forms of the verb, the infinitive of a transitive verb has a direct object: I saw him drive a motor-car. I hope to see you there. •The infinitive is modified by an adverb: You must handle this box carefully. Her aim is to speak English fluently Infinitive in modern English language is also the most segregate form of the verb that only names the action. Thus, the infinitive has nominal characteristics that are realized through its syntactic function. That is that the infinitive can be used in the sentences: • as the subject: To wait seemed foolish when decisive action was required. • as the object: Everyone wanted to go. The particle to is the former marker of the infinitive that differs it from other homonymous personal forms when actually the formal indicator of person is any type of the correlating subject including the infinitive. When it is present, it is generally considered to be a part of the infinitive then known as the full infinitive (or to-infinitive). In the course of time particle to lost its meaning of direction or purpose, and became merely the sign of the infinitive: I went to the shop to buy (purpose). If the infinitive is preceded by the modal verb as the part of the modal verbal subject, the last one is itself the marker of the infinitive as the modal verb without the following infinitive can be used only in structural representations, but such usage is always anaphoric and therefore it means that in previous parts of the text it was followed by the infinitive: 'I can't be bothered now to wrap anything up.' — 'Neither can I, old boy.' (Waine)3 Иванова И. П., Бурлакова В. В., Почепцов Г. Г. Теоретическая грамматика современного английского языка: Учебник./ — М.: Высш. школа, 1981. —285 с. 90 к. 3 9 When the particle is absent, the infinitive is said to be a bare infinitive; and there is a controversy about whether it should be separated from the main word of the infinitive. The infinitive without particle to is not of the primary usage in Modern English. It is used in a rather limited number of contexts, stil some of these are quite common: a) in combination with the auxiliary and modal verbs shall, will do, may, can, must (modal verb ought is an exception – the following infinitive is always used with particle to): It must be done at all costs. b) after some verbs expressing sense perceptions: to hear, to see, to feel, to perceive: I felt somebody touch my hend in the darkness. c) after the verb to know with meaning close to the verbs to observe or to see: This is the most sudden thing I've ever known him do. d) after the verbs to watch, to notice, to observe; to make meaning змушувати and to let meaning дозволяти, допускати; to bid; also after the expression won't have: What made you come so early? Don't let the fire go out. I bade him go out. She watched the children play in the yard. I won't have you say such things. e) after the expressions like had better, would rather, would sooner, cannot but, nothing but, cannot choose but etc Не said he would rather stay at home. (Н. Р.) George said we had better get the canvas up first (J. J.) f) after the verb to know in the sense of to experience, to observe: Have you ever known me tell a lie? g) in infinitive sentences with why at the beginning when the infinitive has the force of a predicate: Why not go to the cinema? The particle to is sometimes separated from the infinitive by an adverb; this construction is called a "split infinitive": We seek to adequately and sincerely persuade you of our gratitude.The construction got its name and ill fame many centuries after it first appeared in English, but during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries great numbers of split infinitives appeared in print, and many 10 complaints followed. People have been splitting infinitives since the 14th century, and some of the most noteworthy splitters include John Donne, Samuel Pepys, Daniel Defoe, Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Johnson, William Wordsworth, Abraham Lincoln, George Eliot, Henry James, and Willa Cather4. Thus, departing from the following features of the infinitive, we are able to state such functions of the infinitive in the sentence: • The infinitive may be used as the subject: To ascend the mountain was a hard task. In case an infinitive phrase is used, it is sometimes placed after the predicate. Then the sentence begins with the pronoun it (anticipatory it), e.g. it is necessary to, it is important to, it is good (better) to, it is useless to, it is not much use to, it is quite possible to, etc.: It is impossible to do it in so short a time. It is of no use to go there this morning. • It may also be used as the predicative: Our intention was to help you. • Used as part of a compound verbal predicate the infinitive is associated with the finite form of: a) modal verbs can, must, may, ought, shall, will, also to have and to be used as modal equivalents the infinitive becomes a part of a compound verbal modal predicate: We must not not force him any more. b) verbs denoting the beginning, the end or the duration of an action (to begin, to come on, to start, to continue etc) the infinitive becomes a part of a compound verbal aspect predicate: She continued to talk as if someboda was listening. To this group also belong the constructions used to+infinitive and would+infinitive which express repeated actions in the past, and to fail to+infinitive which expresses an unsuccessful attempt to carry out an action: You can easily do it without my help. He failed to understand my meaning. 4 The American Heritage. Book of English Usage. A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English. 1996 11 • The infinitive can be used as the object to a number of verbs as: to want, to wish, to care, to like, to prefer, to choose, to agree, to consent, to promise, to undertake, to mean, to intend, to expect, to decide, to determine, to hope, to try, to attempt, to ask, to beg, to entreat, to manage, to begin, to trouble, to forget, to learn, to pretend, can't bear, can't afford, etc: Don't trouble to lock the front door, I shall be back in no time. I can't bear to see you cry; some adjectives and adjectivized participles like able, unable, certain, sure, likely, willing, unwilling, inclined, disinclined, worthy, eager, anxious, sorry, glad, content, delighted, afraid, impatient, fit, pleasant, unpleasant, etc.: The question is hard to solve. I am eager to hear your story. • Being used as an attribute the infinitive often has modal force: It is the only thing to do (that can be done); or implies more or less prominent idea of purpose: This is a nice dress to wear for the wedding. What is important is that English infinitive has a wider range of modifiers that it’s Ukrainian correlare: abstract and class nouns, indefinite pronouns, ordinal numerals and tha adjective last5. An attributive infinitive often retains the preposition which is used in a construction where the same verb is followed by an object: She is not an easy person to live with. • The infinitive can be an adverbial modifier of: a) purpose: She has gone to fetch a piece of chalk. Very often the infinitive of purpose may be preceded by in order to or so as: I have come here in order to help you. b) result or consequence, especially in combination with demonstrative pronoun such or the adverbs enough, so, too. After so and such, as to is generally used: His tone was such as to allow no contradiction. She knew French well enough to read books. В.Л. Каушанская, Р.Л. Ковнер, О.Н. Кожевникова, Е.В. Прокофьева, З.М. Райнес, С.Е. Сквирская, Ф.Я. Цырлина. Грамматика английского языка (на английском языке). – М.: «Страт», 2000 – ст. 318. 5 12 c) comparison or manner with an additional meaning of purpose, introduced by the conjunctions as if and as though: She made a step towards the door as if to close it. d) attendant circumstances (although many grammarians refer it to the adverbial modifier of result): She closed the door after him, never to see him again. • The infinitive can also be used as parenthesis, implying the additional meaning to the whole sentence: To tell the truth, I’m not very fond of this idea. Nevertheless, these functions of the infinitive, though varied, do not make it unique which leads to the further controvertial interchangeability with other verbals. I.2.2. The gerund The gerund is one of the most troublesome areas of English grammar, for example like the word having: We were talking about John having a sabbatical. The trouble with words like having in this example is that they are halfverb and half-noun, which makes them a serious challenge for any theory of grammatical structure. The facts are well known and uncontentious, but there is a great deal of disagreement about precisely, or even approximately, how to accommodate gerunds. We can easily summarise the main facts, as illustrated by having in the above example. It must be a verb, in fact an example of the ordinary verb have, because it has a bare subject and a bare direct object and it can be modified by not or an adverb: We were talking about John not having a sabbatical. These are characteristics which not only distinguish verbs from nouns but also distinguish them, at least in combination, from other word classes. On the other hand, it must also be a noun because the phrase that it heads is used as the object of a preposition (about), and could be used in any other position where plain noun-phrases are possible: John having a sabbatical upset Bill. 13 The word having must be a noun if these positions are indeed reserved for nounphrases and if noun-phrases must be headed by nouns, i.e. if we maintain the principle of endocentricity. As we shall see below, one way to reconcile these conflicting facts is to weaken this principle, but this is a high price to pay for a solution. Generally speaking, the gerund is a verbal that ends in -ing and functions as a noun. The gerund serves as the verbal name of a process, but its substantive quality is more strongly pronounced than that of the infinitive аs the gerund can be modified by a noun in the possessive case or its pronominal equivalents and it can be used with prepositions.6 However, since a gerund functions as a noun, it occupies some positions in a sentence that a noun ordinarily would, for example: subject, direct object, subject complement, and object of preposition. Thus the gerund as well as the other verbals has its characteristic nominal and verbal features. The strongest evidence for the nominal nature of verbal gerunds comes from the external distribution of verbal gerund phrases. They appear in contexts where otherwise only noun phrases can occur. For one, clauses, unlike NPs, are generally prohibited from occurring sentence internally. • the Gerund can be used in the function of subject, (direct or prepositional) object and predicative: Swimming is just delightful there. I like making people happy. My favourite out-door winter sport is figure skating. • when used as an attribute or adverbial modifier, the gerund also clearly shows its nominal character as it can be preceded by a preposition, which is a formal mark of the noun: I can boast of having seen Linden. In going down town I met an old friend of mine. • it can be modified by a possessive pronoun (specific gerund pattern): His being so slow is very annoying. 6 Блох М. Я Теоретическая грамматика английского языка: Учебник. Для студентов филол. фак. ун-тов и фак. англ. яз. педвузов. — М.: Высш. школа, 1983.— с. 383 14 • it can be modified by a noun in the Possessive Case (specific gerund pattern): She objected to her son’s travelling by sea. Among verbal characteristics of the gerund such shoud be mentioned: • as well as the infinitive it has voice and tense distinctions, according to which the following forms are distinguished: Indefinite Gerund Active is the only simple form of the gerund. It expresses the simultaneous action with the one expressed by the finite verb that is why it may refer to any of three times – present, past or future. It is formed by the addition of the suffix –ing to the verbal stem, e.g. to dance – dancing, to smoke – smoking. This way of the formation of the simple form is similar to the corresponding form of the participle I: She insists on starting at six o'clock. I rely on his doing it properly. Perfect Gerund Active is formed with the help of auxiliary verb to have in the form of the simple gerund and the participle II of the finite verb, e.g. having danced. It denotes the action prior to the finite verb. The indefinite gerund is commonly used instead of the perfect gerund after the prepositions on (upon) and after because the meaning of the preposition itself indicates that the action of the gerund precedes that of the finite verb: I am surprised at his having done it. He told me of his having seen her. Indefinite Gerund Passive is formed with the help of auxiliary verb to be in the form of the simple gerund and the participle II of the finite verb, e.g. being smoked. Perfect Gerund Passive is formed with the help of auxiliary verb to be in the form of the perfect gerund and the participle II of the finite verb, e.g. having been smoked. The fact that some verbal gerunds take accusative objects is therefore not especially striking. What is important is that a verbal gerund, unlike a nominal gerund, takes the same complements as the verb from which it is derived: • in common with the finite forms it can be use with modifying adverb: She burst out laughing hysterically. 15 • the gerund (of transitive verbs) can take a direct object: I had made a good progress in speaking their language. Departing from the following characteristics of the gerund, we are able to state such functions of the gerund in the sentence: • First of all, the gerund may be used as subject of the sentence: Travelling might satisfy your desire for new experiences. The gerund is used as the subject at the beginning of the sentence if there is no other word that can be the subject. But when the subject of the sentence is a gerundial phrase, it sometimes can be placed after the predicate, the sentence beginning with the anticipatory it: There is no use complaining about the weather now. Although this statement is somehow controversial as in this situation it may be easily taken as the subject of the sentence. Therefore, the rest of the sentence performs the function of the predicate. The gerund may be also used as subject in the construction like there is no: There is no getting rid of that troublesome person. • The gerund may also be used as a predicative: The only thing he could in that situation was making no sound at all. As predicative the gerund may express either state or identity: Peter was against your joining us. John’s hobby is collecting all butterflies. • As part of a compound verbal predicate it can be associated with the finite form of verbs denoting the beginning, the duration or the end of an action such as to begin, to start, to go on, to keep on, to continue, to stop, to leave off, to finish, to give up, to have done (to finish). In combination with phrasal verbs the gerund forms a compound verbal predicate of aspect. He kept on bothering me with his questions. This is the only function of the gerund that is not characteristic of the noun, for it is caused by the verbal character of the gerund. A gerundial predicative construction cannot form part of a compound verbal predicate. 16 • In common with all non-finite verbal forms it can be used in the function of the object, basically as the direct and prepositional object. To verbs associated only with the gerund, such as to avoid, to delay, to put off, to postpone, to mind (negative and interrogative forms), to excuse, to fancy, to burst out, to want, to require, to need, can't help, etc, the gerund performs the function of the direct object: Would you mind ringing me up to-morrow? Excuse my interrupting you. To this group belong alo the verbs which can be associated with both the gerund and the infinitive (to neglect, to omit, to like, to dislike, to hate, to detest, to prefer, to enjoy, to regret, to remember, to forget, to intend, to attempt, to propose; can't bear, can't afford) and the adjectives like, busy and worth: She preferred staying (or to stay) at home on such a wet day. I never felt less like laughing. • There is a list of words to which the gerund may be used as prepositional object. To them belong first of all such verbs as to think of, to persist in, to rely on, to depend on, to object to, to thank for, to prevent from, to insist on, to succeed in, to devote to, to assist in, etc: She assisted the gardener in planting the flowers. Secondly, such adjectives and past participles used mostly predicatively as fond of, tired of, proud of, ignorant of, used to; and nouns derived from verbs and adjectives such as hope, difficulty, necessity, possibility, etc.: Gradually I became used to seeing the gentleman with the black whiskers. (Dickens.) There was no chance of getting an answer before the end of the week. • In the sentence the gerund may serve as attribute always with a preposition (in most cases of) to such nouns as pleasure, idea, risk, method, and way: The date of my leaving for the country is uncertain. 17 • As adverbial modifier it is always used with a preposition. I this case the functions of the gerund are distributed as the adverbial modifiers: a) of time, in combination with the prepositions after, before, on, upon, in, at: Before filling your fountain-pen, you should carefully clean it. b) of manner, in combination with the prepositions by or in: She only annoyed me by saying how good my performance was. c) of purpose, mainly use with preposition for: This room was usully used for their rehersals. d) of condition, in combination with the preposition witout: He had no right to come botering me without a spetial permission. e) of attendand circumstances, also preceded by the preposition witout: He easily entered the buildind without even being noticed. f) of cause, introduced by the prepositions for, for fear of, owing to: I could not speak for laughing. g) of concession, preceded by the preposition in spite of: I spite of being very late, he was stil working on his course paper. It is clear that the gerund in finction of the adverbial modifier is introduced by rather limited number of the prepositions, which means that in defining the actual function of the gerund in the sentence one shold rely mostly on its meaning and contaxt in which the gerund is used. I.2.3. The participle As it is well known, English and other languages have three kinds of participles which surface with the same form, namely perfect, passive and adjectival passive participles: a. I have written three poems (perfect). b. Three poems were written by me ( passive). c. The poems are well-written (adjectival passive). 18 In order to account for the similarity of the participles in 1980 Lieber 7 proposed that adjectival passives are formed from verbal (perfect and passive) participles by affixation of a null adjectival morpheme. Bresnan (1982) pointed out, though, that adjectival participles systematically have a passive meaning. An expression like the eaten dog means the dog that ‘was’ eaten and not the dog that ‘has’ eaten, i.e. adjectival participles are closer to passive than to perfect participles. Bresnan concluded that the passive participle only, and not the perfect participle, constitutes the input to the adjectival passive formation rule. On this view, passive participles are ambiguous: they are either adjectival or verbal. This classification though is not commonly used in theoretical grammar, being substituded by the commonly recognized division into participle I and participle II. This work is futher concentrated on these groups. Generally the participle is a non-finite form of the verb characterised with verbal, adjectival and adverbial features. But as the English participle has lost its forms of agreement with the noun with which it is connected, and is no longer formally bound to that noun, it is sometimes attracted by the verb, thus assuming the force of an adverbial modifier. The participle as a general notion possesses some features characteristic to the verb. First of all, it has voice distinction, basically the active and passive forms. As for the tense distinction, it turned out to be a matter of some controversy. Like that of all verbals, the category of tense of the Participle is expressed relatively. Still some scholars like Laimutis Valeika maintain the point that the participle does not express tense distinctions, appealing to the fact that actually the relative tense is not the category of tense in its full meaning. Departing from this statement a simple conclusion arises – all verbals have no category of tense. Such estimations, of course have particular grounds, although we should admit that they are not world-wide recognized. 7 Lieber, Rochelle 1980 On the Organization of the Lexicon. Ph.D. Dissertation. MIT. 19 As a verb, the participle has distinctions of voice and tense. Accordin to them in Modern English there are two distinct participles - present participles and past participles or correspondingly participle I and participle II. Participle I is the non-finite form of the verb which combines the properties of the verb and those of the adjective and adverb, serving as qualifying processual name. In its outer form the present participle is wholly homonymous with the gerund and distinguishes the same grammatical categories. Like all the verbals it has no categorical time distinctions, and the attribute "present" in its conventional name is not immediately explanatory; it is used from force of tradition. Participle I can be formed from both transitive and intransitive verbs, in contrast to participle II that can be rendered only from transitive ones. Participle I present active and passive expresses that the action of the participle is simultaneous with the action of the finite form of the verb in the sentence: When coming here, I met an old friend of mine. Being left alone, I thought about my past life. Participle I perfect denotes that the action of the participle precedes the action of the finite form of the verb in the sentences: Having written the letter, I went to post it. I was lying in the bed, having already been said to live the house. Since participle I possesses some traits of adjective and adverb, the present participle is not only dual, but triple by its lexico-grammatical properties, which is displayed in its combinability, as well as in its syntactic functions. Following the verb-combination patterns, patticiple I can be combined with nouns expressing the object of the action, nouns expressing the subject of the action, with modifying adverbs and auxiliary finite verbs in the analytical forms of the verb. To verbal features the use of the present participle as secondary predicate can also be attributed: Believing that Juliet was dead, Romeo decided to kill himself. 20 Like adjectives participle I is easily combinable with the modified nouns and some modifying adverbs that is be used as an attribute – generally as a postposed attribute, e.g. The man talking to John is my boss. More problematic is the use of the present participle in preposition to the noun: the point is that such attributes must denote permanent or characteristic properties. The girl is smiling/the smiling girl. But if the process of smiling is considered as habitual, the word-combination the smiling girl is acceptable. Like adverbs participle I can be combined with the modified verbs. The past participle of a transitive verb is passive; in English there is no corresponding active participle. Past participle can be characterized by the absence of its own paradigm. What is important is that participle II has its own set of characteristics which differ it fron other verbals and participle I as well. Its main verbal feature is the ability of participation in the structure of the verbal predicate: The bridge was destroyed by aan earthquake; and the use as secondary predicate: Her belief in justice, though crushed, was not distroyed. Its adjectival peculiarity is its attributive function: She looked at the broken cup. Thus, summing up the the following features of the present and past participles, we are able to state such general functions of the participles in the sentence: • When the participle is connected with some noun-word in the sentence it can be used: a) as a predicative: The children were neatly dressed and looked strong and healthy. b) as an attribute: The ground is carpeted with fallen leaves. A heavy snow is falling, a fine, pricking, whipping snow, borne forward by a swift wind in long, thin lines. 21 • When an attributive participle phrase follows the noun, it is equivalent to a whole attributive clause, e.g.: We found a cheerful company assembled round a glowing fire (which was assembled round a glowing fire). • There can be cases when participles used as attributes or predicatives lose their connection with the verb from which they have been derived and become mere adjectives: The story is amusing. The book is interesting. • When connected with a verb as an adverbialized participle it expresses relations: a) of time: Hearing a noise, we stopped talking. Having arrived at this decision, she immediately felt more cheerful. Sometimes a participle phrase expressing adverbial relations of time is introduced by the conjunctions while and when and may be considered as a result of ellipsis: When coming here (when I was coming here), I met an old friend of mine. b) of cause: Not having understood the directions clearly, I couldn't find the way in the darkness. c) of manner or attending circumstances: Regardless of the weather, the ferry operates night and day. d) of condition: This small crime, if discovered, will bring them to the court. e) of comparison: She looked into the boys eyes as if lost in their depth. g) of concession: Her brother, though deeply depressed, seemed rather cheerful. 22 • If an adverbial phrase contains a participle and a noun preceded by with or without, it expresses attending circumstances. In this case, the relation between the noun and the participle is that of secondary subject and secondary predicate (a complex adverbial modifier): He fell asleep with his candle lit (while his candle was lit). • The participle may be used as the part of a complex object: I saw that man talking to you on the stairs. Stil, there are instances where the syntactical function of the participle may be interpreted in two ways. For example: The wind rustling among trees and bushes flung the young leaves skywards. The participle rustling may be considered either as an attribute to the subject wind or as an adverbial modifier of manner to the predicate flung. 23 CHAPTER II. Controversy in usage of the non-finite forms As it was already previously mentioned, one of the most controvertial classes of verbals is the gerund. Its practical usage is constantly complicated by the great possibility of being confused with other verals or being misused. That is why futher the main attention is paid to the peculiarities of non-finite forms distinction. II.1. The gerund and the infinitive One of the many problems which confront non-natural English speakers is knowing when to use the infinitive and when to use the gerund in verb complementation. More specifically, learners are often uncertain as to which complement to choose both in those cases where only one is possible as in ’she refuses to go’ and ‘she enjoys going’ and in those where either, at least from a structural perspective, may be possible: ‘she prefers to go/going’. Since a corresponding gerund/infinitive contrast does not exist in most languages, including the Scandinavian, non-native speakers, who do not appreciate the subtle semantics that distinguish the two constructions, frequently fail to select the appropriate complement. Here are three examples taken from student writings. She has not finished to do her homework. The horse practiced to leap over the fence. I’m not allowed having lunch in the library. The traditional method for distinguishing gerund/infinitive complementation usually involves long lists of head verbs and their respective complements. The problem is that lists can never be complete since, as W. Petrovitz8 observes, it is doubtful whether the head verbs in, for example, ‘the coach criticized drinking before the game’ and ‘the law encourages conserving natural resources’ would be found on them. The other problem is that lists do not 8 Petrovitz, W. (2001). The sequencing of verbal complement structures. ETL Journal 55.2. 172-177. 24 account for those verbs that can occur with either construction. Since these verbs are clearly not amenable to listing, most grammar books often appeal to explanations for such verbs as forget, regret, and try, where there is a perceptible difference in meaning depending on complement choice. On the other hand, in the case of verbs like begin, like, and cease, where a semantic difference is not so obvious, complementation is frequently regarded as essentially a matter of free variation, i.e., either the gerund or infinitive may be chosen ‘with little or no change in meaning’9. At this point, the suggestion of Swedish scholar Michael Wherrity10 from Karlstad University can be mentioned, whose theory of complementation is based on a meaning which is associated with a particular linguistic form (e.g. to, -ing). He had assigned such basic meaning to to as orientation towards a point and –ing as a process. The basic meaning of to is obvious when it is used prepositionally to indicate relationships in the spatial domain where it normally suggests some distance between entities: It is close to the door. On a more abstract level it is also operative when to appears in the infinitive construction: She hopes to finish before the bell. Here, the ‘point’ specified in the basic meaning can be understood as a goal towards which the activity of the head verbs (hope) is directed. There is a before/after relationship between the head and complement verbs which has its cognitive source in the distance relationship signalled by to when used prepositionally. Process can be conceived of either as an actual entity involved in an ongoing activity (the boiling water) or as an implicit or imaginary entity experiencing an activity: Jogging is a healthy form of exercise. When choosing a to or an –ing complement, speakers give preference to the meaning which is suitable to the message they wish to communicate. Since basic meanings are maximally general and therefore quite imprecise, it is really a 9 Azar, B.S. (1989). Understanding and Using English Grammar. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents. 10 Wherrity, M.P. (2001). The Gerund Infinitive Contrast in English Verb Complementation. Ann Arbor , Mich: UMI 25 matter of choosing the meaning which is less inappropriate to the message; there is no perfect fit. Actually, speakers just use the meaning which is best suitable to expressing what they wish to say, e.g.: I hope to win the lottery. In this example, the basic meaning of to is appropriate for imparting messages of ‘futurity’ and ‘contingency’ due to its future orientation from a ‘before’ point in time in the direction of a goal which represents an ‘after’ point in time. This before/after component is clearly not present process, which is more appropriate for suggesting messages of simultaneous activity between head and complement verbs. With the infinitive complement, however, the temporally distancing function of to, suggesting a before/after relationship between complement and head verbs, is semantically compatible with the future thrust of hope. This can be contrasted with the following: She enjoyed hearing the performance. The basic meaning of –ing is suited to imparting a message of an experience occurring simultaneously with the activity of the head verb. One cannot ‘enjoy’ something without experiencing it. This holds even in general statements such as ‘she enjoys swimming’ which can be paraphrased as ‘whenever she goes swimming, she enjoys it’. By contrast, the to complement would not work here due to its temporally distancing function. But stil there are a variety of ways in which the hearer might interpret the activity of the complement verb in gerund and infinitive constructions. These ‘messages’ can be roughly classified as follows: to-type messages and ing-type messages which though are not to be considered as discrete categories, since they frequently overlap in communication. II.2. Participle I and the gerund The problem of the gerund/participle contribution lies mostly in their lexico-grammatical similarity as of two non-finite verb forms in –ing. This fact 26 makes a lot of scholars even to doubt their belonging to different subclasses of verbals but being the same form used in different functions. According to the Prof. Blokh, the ground for raising this problem is quite essential, since the outer structure of the two elements of the verbal system is absolutely identical: they are outwardly the same when viewed in isolation. In the American linguistic tradition which can be traced back to the school of Descriptive Linguistics the two forms are eve recognised as one integral V-ing. This opinion is supported be such famous grammarians as V. Plotkin, L. Barkhudarov. They confirm their opinion by the paradigmatic similarity of these verbals. Such scholars as A.Smirnitsky and B. Streng strictly distinguish between these two forms, while for example B. Ilyish stands on the point that both opinions deserve to be considered as equal due to the mutual complexity of the issue. Again, in case the gerund and the participle are confused, it is the participle that is displased. The identity between the two forms leads to loose and unaccountable gerund constructions that will probably be swept away, as so many other inaccuracies have been, with the advance of grammatical consciousness. Returning to Michael Wherrity’s assumption that the gerund actually denotes the process, this idea may be transferred to H.W. Fowler’s representation of relation between the gerund and the participle as respectively between the adjective and the noun. On the assumption of the participle being an adjective, it should be in agreement with a noun or pronoun; if the gerund respectively is a noun, of which it should be possible to say clearly whether, and why, it is in the subjective, objective, or possessive case. Although being obwiously outdated, Fowler’s ideas are somehow consonant with the modern set of features that distinguish the gerund from the participle. First of all the gerund is used after different prepositions (of, after, before, by, for, from, in, on, without), e.g.: There are two ways of measuring engine power. The other sign that indicates that it is the gerund that actually was 27 usd is the presence of possessive pronoun (my, her, etc) before the –ing form: The professor approved of my solving problem. To this group belongs also the occurrence of nouns in the possessive and the common cases, e.g.: We know of Newton’s having developed the principles of mechanics. The gerund and the participle I can both perform the function of the “left attribute”. In this case, the distinction berween them is based exclusively on the meaning content. It shoul be taken into account that the participle expresses the action determined by the noun, e.g. a writing man. At the same time, the gerund is the marker of purpose like in a writing table. Although these indicators are apparently clear, various degrees of ambiguity are stil possible: Can he conceive Matthew Arnold permitting such a book to be written and published about himself? – It can be impossible to say, whatever the context, whether the writer of the first intended a gerund or a participle. And no doubt that end will be secured by the Commission sitting in Paris.— The previous sentence would probably have decided the question. If sitting is a participle, the meaning is that the end will be secured by the Commission, which is described by way of identification as the one sitting in Paris. If sitting is gerund, the end will be secured by the wise choice of Paris and not another place for its scene. If Commission's were written, there could be no doubt the latter was the meaning. With Commission, there is, by present usage, absolutely no means of deciding between the two meanings apart from possible light in the context. Those who know least of them [the virtues] know very well how much they are concerned in other people having them.— Though grammar (again as modified by present usage) leaves the question open, the meaning of the sentence is practically decisive by itself. Here common sense is able to tell us, though grammar gives the question up, that what is interesting is not the other people who have them, but the question whether other people have them. 28 II.3. Nominal phrases and gerundial constructions The gerund (gerundial constructions), on the assumption of its nominal characteristics, sometimes can be easily used in any of the positions where plain noun-phrases are possible. In this case, is is just a matter of speakers choice which construction is to be used and better suits the communicative and stylistical aim. But the fact which should be born in mind is the existence of constructions in which only a gerund phrase, and no other kind of noun phrase, may be used 11. On the one hand there are constructions where the gerund phrase is extraposed: a. It’s / There’s no use telling him anything. b. There’s no point telling him anything. c. It’s scarcely worth (while) you / your going home. d. It’s pointless buying so much food. In none of these examples is it possible to replace the gerund phrase by an ordinary noun phrase: a. *It’s no use a big fuss. b. *There’s no point anything else. c. *It’s scarcely worthwhile a lot of work. d. *It’s pointless purchase of food.12 On the other hand, there is at least one verb, prevent, which only allows a gerund phrase after its complement preposition. They prevented us from finishing it / *its completion. In short, these are all cases where some construction selects specifically for gerund phrases, so it is important that these should be distinguishable from other noun phrases. These facts about gerund selection are important because they confuse the simple view of the relationship between the nominal and verbal characteristics of gerunds. If we think of a gerund in terms of the phrase that it heads, the following generalisation is almost true that the phrase headed by a gerund is an ordinary 11 Malouf, R. (1998). Mixed Categories in the Hierarchical Lexicon. Stanford University PhD dissertation. 12 Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G. and Svartvik, J. (1985). A Comprehensive Grammar of theEnglish Language. Loered don: Longman. 29 clause as far as its internal structure is concerned, but an ordinary noun-phrase in terms of its external distribution. 30 Conclusion Non-finite forms of the verb in the Endlish language have the wide range of functional application in the sentence. Their functions proceed from the peculiarities of their develorment and as a result the mixed nature of the verbals – they are closely contiguous to non-verbal categories taking their features from other than the verb parts of speech, and basically the gerund and the infinitive from the noun and the participle from the adverb. Thus, from the functional perspective non-finite forms of the verb are almost universal, being unable to perform only the function of the predicate but quite able of being a part of the compound verbal predicate. Although some scholars do agree that verbals may be used in the sentence as the plenipotentiary predicate like in the simple example ‘The effect of her words was terrifying’ where participle I is considered to be the predicate13. In many cases the functional distribution of non-finite ferms of the verb allows verbals to be easily substituted by one another in the same syntactic context. As the only suitable criterion of their differentiation can serve the meaning content of the message that the speaker or the writer wants to apply. Thus, in the ambiguous pair gerund/infinitive this opposition can be transformed to another one – orientation towards a poin/ process. The same situation is observable in the relations between gerundial and nominal phrases which often can be interchangeable without any restrictions by the meaning. The gerund/participle relations are complicated by the fact that participle I has the same ending –ing. In such a way the total homonimy of forms may cause the misinterpreting of the function of the verbal and the following misunderstanding of the main idea of the utterance. As a conclusion we can say that the practical usage of non-finite forms of the verb is closely connected to the problem of their functional proximity. В.Л. Каушанская, Р.Л. Ковнер, О.Н. Кожевникова, Е.В. Прокофьева, З.М. Райнес, С.Е. Сквирская, Ф.Я. Цырлина. Грамматика английского языка (на английском языке). – М.: «Страт», 2000 – ст. 318. 13 31 Резюме Метою цієї курсової роботи є дослідити функціональне розмаїття безособових форм дієслова в англійській мові та їх практичне використання, враховуючи спільність їх історичних та функціональних витоків, а отже і проблему можливості їх кореляції в ідентичних синтаксичних умовах. Поєднуючи у собі характеристики різних частин мови, вербалії досягають чи не найповнішої функціональної різнобічності, тим самим ускладнюючи процес їх перерозподілення відповідно до контексту. Така функціональна, а часом і формальна, омонімічність призводить до утворення пар-опозицій, єдина можливість уникнути яких зокрема полягає в урахуванні смислового навантаження повідомлення, що водночас і полегшує, і ускладнює процес диференціації, адже авторські інтенції не завжди чітко зрозумілі з контексту. 32 REFERENCE LITERATURE 1. Azar, B.S. (1989). Understanding and Using English Grammar. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents. – p. 303-309. 2. Chrystal D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. – Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995. – 489 p. 3. Duffley P.J. The English infinitive. – London; New York, 1992. - 168 p. 4. E. M. Gordon,I. P. Crylova“A Grammar of Present-day of English (Parts of Speech)”2nd addition 1980 «Высшая Школа» Москва – p. 448. 5. Hudson R. Gerunds and multiple default inheritance. Linguistics Association of Great Britain. – p. 418-430. 6. Hudson, R. (1999a). Encyclopedia of English Grammar and Word Grammar. http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/enc.htm 7. Ilyish B. History of the English Language. - Л., 1973. – 324с 8. Koshevaya I.G. The Theory of Grammar, M., 1982 – 94-105. 9. Lieber, Rochelle (1980). On the Organization of the Lexicon. Bloomington: IULC. 10.Malouf, R. (1998). Mixed Categories in the Hierarchical Lexicon. Stanford University. 11.Petrovitz, W. (2001). The sequencing of verbal complement structures. ETL Journal 55.2. 172-177. 12.Pullum, G. K. 1991. English nominal gerund phrases as noun phrases with verb-phrase heads. Linguistics – p.29. 13.Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G. and Svartvik, J. (1985). A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman. 445p. 14.Reuland, E. 1983. Governing -ing. Linguistic Inquiry –p. 136. 15.The American Heritage Book of English Usage. A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English. 1996. - p. 55-60. 33 16.Wherrity, M.P. (2001). The Gerund Infinitive Contrast in English Verb Complementation. Ann Arbor , Mich: UMI- 11p. 17.Блох М. Я Теоретическая грамматика английского языка: Учебник. Для студентов филол. фак. ун-тов и фак. англ. яз. педвузов. — М.: Высш. школа, 1983.— с. 383 18.В.Л. Каушанская, Р.Л. Ковнер, О.Н. Кожевникова, Е.В. Прокофьева, З.М. Райнес, С.Е. Сквирская, Ф.Я. Цырлина. Грамматика английского языка (на английском языке). – М.: «Страт», 2000 – ст. 318. 19.Иванова И. П., Бурлакова В. В., Почепцов Г. Г. Теоретическая грамматика современного английского языка: Учебник./ — М.: Высш. школа, 1981. —285 с. 20.Ильиш Б.А. Строй современного английского языка – Л.: Просвещение, 1971. – 365с. 21.Практический курс английского языка. 4 курс: Учеб. для педвузов по спец. «Иностр. яз.» / Под ред. В.Д. Аракина. - 4-е изд., перераб. и доп. М.: Гуманит, изд. центр ВЛАДОС, 2000. - 336 с. 22.Расторгуева Т. А. History of the english language. М Высшая школа 1972г. 176 с 23.Смирницкий А.И. Морфология английского языка. М.: Ин.яз., 1959. – с. 440. 24.Слюсарева Н.А. Проблемы функциональной морфологии современного английского языка. — М.,1986 – c.65 -73. 34