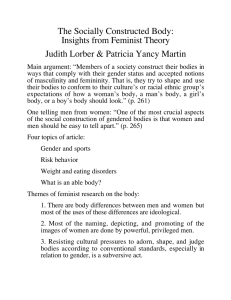

Gender Matters in Global Politics A Feminist Introduction to International Relations (Laura J. Shepherd) (z-lib.org)

advertisement