Locative alternation and two levels of

verb meaning

SEIZI IWATA*

Abstract

Verbs like load or spray are known to alternate between two variants

(John sprayed paint onto the wall/John sprayed the wall with paint).

Both Rappaport and Levin (1988) and Pinker (1989) derive one variant

from the other, but these lexical rule approaches have a number of problems. This paper argues for a form-meaning correspondence model which

distinguishes between two levels of verb meaning: that of a lexical head

spray on the one hand and that of a phrasal constituent spray paint onto

the wall or spray the wall with paint on the other. Locative alternation

stems from the fact that a frame semantic scene encoded by spray can be

construed in two alternate ways. This proposed model allows us to account

for the data straightforwardly without su¤ering from the problems created

by lexical rule approaches. This proposed analysis is fundamentally the

same as Goldberg’s (1995) in being a version of Construction Grammar

approach. But unlike Goldberg’s Correspondence Principle-based account,

my analysis makes the most of the semantic compatibility between verbs

and constructions, thereby giving a more straightforward account of locative alternation.

Keywords:

locative alternation; L-meaning/P-meaning distinction; Construction Grammar; frame semantics; thematic core.

1. Introduction

A class of verbs called locative alternation verbs exhibit two variants, a

locative variant and a with variant in the terms of Rappaport and Levin

(1988).

(1)

a.

b.

Jack sprayed paint onto the wall. (locative variant)

Jack sprayed the wall with paint. (with variant)

Cognitive Linguistics 16–2 (2005), 355–407

0936–5907/05/0016–0355

6 Walter de Gruyter

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

356

(2)

S. Iwata

a.

b.

Bill loaded cartons onto the truck.

Bill loaded the truck with cartons.

The locative alternation phenomenon has attracted much attention because of a number of characteristics. The following discussion is concerned with the fundamental question of why a single verb appears in

more than one syntactic frame.

This paper is organized as follows: After reviewing the lexical rule approaches in Rappaport and Levin (1988) and Pinker (1989) and pointing

out their problems, Section 3 proposes an alternative analysis based on a

form-meaning correspondence model which crucially draws on two levels

of verb meaning. Section 4 shows the advantages of the proposed analysis

over lexical rule approaches, and Section 5 considers why lexical rule approaches look plausible despite their fundamental problems. Section 6

compares the proposed analysis with Goldberg’s (1995) Construction

Grammar approach, thereby showing the fundamental similarities between the two accounts on the one hand, and pointing out problems of

Goldberg’s Correspondence Principle-based account on the other. Section

7 shows, through case studies, that it is semantic compatibility between

verbs and constructions, rather than lexical profiling as defined by Goldberg, that determines the integration of verbs and constructions. And Section 8 considers how the proposed analysis can be extended to handle locative alternation involving morphological derivation.

2.

Lexical rule approaches

Two representative previous analyses are Rappaport and Levin (1988)

and Pinker (1989), both resorting to lexical rules.

2.1.

Rappaport and Levin 1988

Rappaport and Levin (1988) posit the semantic structures in (3), where

(3a) is for a locative variant and (3b) for a with variant.

(3)

a.

b.

load: [x cause [y to come to be at z]/ load]

load: [[x cause [z to come to be in state]]] by means of [x cause

[y to come to be at z]]/ load]

Crucially, (3a) is embedded under BY MEANS OF in (3b), meaning that

a change of state is brought about by means of a change of location. In

other words, a with variant is an extension of a locative variant, the main

clause of (3a) becoming a subordinate clause in (3b).

This analysis raises a number of problems. First, it ensures only

deriving the with variant from the locative variant. However, another

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

357

derivation is also necessary. In addition to locative alternation verbs, we

have both a class of verbs with only a locative version as in (4) and a class

of verbs having only the with version as in (5). A derivation from a locative variant would permit the class of verbs as in (4) as well as locative

alternation verbs, but not that of verbs as in (5).

(4)

(5)

a.

b.

a.

b.

Irv poured water into the glass.

*Irv poured the glass with water.

*She covered a rug over the floor.

She covered the floor with a rug.

Accordingly, there must be a derivation from the with variant as well. But

Rappaport and Levin say nothing about this derivation. Even if they tried

to find an appropriate one, it would be quite di‰cult to do so in their

framework. A conceivable solution is to reverse the means relation, as Inagaki (1989) does. To accommodate a derivation from the with variant,

Inagaki (1989) proposes the following representations for the two variants

of stu¤.

(6)

a.

b.

stuff: [x cause [y to come to be stuffed with z]]

stuff: [[x cause [z to come to be at y]/stuff] in order that [x

cause [y to come to be stuffed with z]]] (Inagaki 1989: 222)

(6b) is to be read as: A change of location is brought about in order for

a change of state to take place. For instance, stu‰ng feathers into the

pillow is brought about in order for stu‰ng the pillow with feathers to

obtain.

This analysis does not work, however. Even apart from its clumsiness,

this paraphrase fails to convey the correct meaning. Stu‰ng feathers into

the pillow is not necessarily done for the purpose of stu‰ng the pillow.

Moreover, in order that does not entail that stu‰ng the pillow is actually realized. Thus appeal to a purpose relation is unsatisfactory in these

respects, and it seems quite di‰cult to come up with an appropriate extension relation that forms a locative variant from a with variant.

Second, the means extension analysis cannot be easily applied to other

complement alternations. As is well-known, verbs other than locative

alternation verbs also exhibit two variants.

verbs of inscribing

(7) a. The jeweler inscribed a motto on the ring.

b. The jeweler inscribed the ring with a motto.

verbs of presenting

(8) a. The judge presented a prize to the winner.

b. The judge presented the winner with a prize.

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

358

S. Iwata

verbs of forceful contact

(9) a. Kevin hit the stick against the wall.

b. Kevin hit the wall with the stick. (Rappaport and Levin 1988:

28–29)

The parallelism between these complement alternations and locative alternations is undoubtedly clear. But the means extension analysis creates

bizarre readings for the with variants: Inscribing the ring with a motto is

brought about by means of inscribing a motto on the ring; presenting the

winner with a prize is brought about by means of presenting a prize to the

winner; hitting the wall with the stick is brought about by means of hitting the stick against the wall. The means extension analysis as it stands

is hardly convincing here.1

2.2.

Pinker 1989

Pinker (1989), essentially following the analysis of Rappaport and Levin

(1988), argues that the locative alternation is e¤ected by a lexical rule that

operates on a semantic structure:

it is a rule that takes a verb containing in its semantic structure the core ‘X causes

Y to move into/onto Z,’ and converts it into a new verb whose semantic structure

contains the core ‘X causes Z to change state by means of moving Y into/onto it.’

(Pinker 1989: 79)

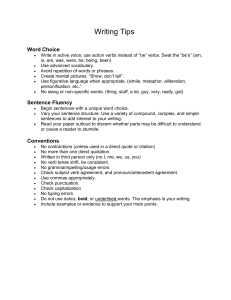

The semantic structures are as shown in Figure 1:

The relevant parts are shown as in (10). The whole EVENT structure

for the locative variant (10a) is embedded in the means clause in (10b).

(10)

a.

b.

EVENT

ACT

e¤ect

EVENT

GO

EVENT

ACT

e¤ect means

EVENT EVENT

GO

The two semantic structures are linked by a bidirectional arrow, because

Pinker assumes that the derivation proceeds in either direction: from the

locative variant to the with variant, or from the with variant to the locative variant. Directionality of the derivation is determined by the possibility of the direct argument standing as sole complement. If the theme NP,

but not the goal NP, stands alone, then the derivation is from the locative

variant to the with variant as in (11). If the goal NP, but not the theme

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

359

EVENT

Effect

ACT THING

THING

[(Bob)]

[(paint)]

EVENT:locational

GO

THING

PATH

(paint)

[ ]

to PLACE

<place-fnctn>

THING

(wall)

EVENT

ACT THING THING effect

[(Bob)] [(wall)]

means

EVENT

EVENT

Effect

GO

THING PROPERTY

ACT THING THING

EVENT

(wall)

GO

THING PATH

to PLACE

<place-fnctn>

THING

Figure 1. Semantic structures of ‘X causes Y to move into/onto Z’ and ‘X causes Z to

change state by means of moving Y into/onto it’

NP, stands alone, then the derivation is from the with variant to the locative variant as in (12). When either argument can stand as sole complement as in (13), the derivation can go in either direction.

(11)

(12)

(13)

a.

b.

a.

b.

a.

b.

He piled the books.

*He piled the shelf.

*He stu¤ed the breadcrumbs.

He stu¤ed the turkey.

He loaded the gun.

He loaded the bullets. (Pinker 1989: 125)

Pinker’s analysis di¤ers from that of Rappaport and Levin in accommodating the derivation that goes from the with variant as well. But the

very mechanism that Pinker introduces so as to guarantee the bidirectionality of derivation is problematic. First, it is rather doubtful whether the

possibility of standing as sole complement truly serves as a diagnostic

for the derivational base. As Pinker himself points out, some verbs allow

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

360

S. Iwata

neither the theme nor the goal argument to stand alone as in (14), and

some verbs allow either argument to stand alone as in (15).

(14)

(15)

a.

b.

c.

d.

a.

b.

c.

d.

John heaped books on the shelf.

John heaped the shelf with books.

*?John heaped the books.

*John heaped the shelf.

John packed books into the box.

John packed the box with books.

John packed the books.

John packed the box. (Pinker 1989: 38–39)

Thus the possibility of sole complement does not always serve as a

diagnostic.

Moreover, the sole complement analysis seems hardly relevant to an

account of locative alternation. It is true that sole complement plays a

significant role in a number of linguistic phenomena, such as adjectival

passives, -able adjectives, middles, and process -ing nominals (Ito 1981;

Levin and Rappaport 1986; Endo 1986; Carrier and Randall 1992). These

phenomena form a natural class, in that they all involve a category

change or suppression of an external argument of the base verb. But the

locative alternation involves neither. It is simply a matter of multiple subcategorization frames and is quite di¤erent in character from the above

class.

The second problem concerns the plausibility of ‘extension.’ For clarity, I repeat (10).

(10)

a.

b.

EVENT

ACT

E¤ect

EVENT

GO

EVENT

ACT

e¤ect means

EVENT EVENT

GO

Pinker maintains that there are both a lexical rule that changes (10a) into

(10b) and one that turns (10b) into (10a). While the former amounts to

lexical subordination, the latter should be an ‘inverse of subordination’.

This means that verbs like stu¤ originally have the semantic structure of

(10b), and that the putative lexical rule deletes the main clause, thereby

promoting the erstwhile subordinate clause into the main clause. This derivation is too powerful and peculiar, and finds no analogue in other linguistic phenomena.

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

361

Finally, Pinker treats locative alternation as a special relationship between two variants. But the alternation is not restricted to the two alternants. Wrap allows three variants.

(16)

a.

b.

c.

She wrapped the baby in a towel.

She wrapped the baby with a towel.

She wrapped a towel around the baby. (Nakau 1994)

Pinker’s analysis has di‰culty in handling (16).2

3. Analysis

3.1.

L-Meaning and P-Meaning

Toward the goal of working out a solution, let us begin by examining

what is actually going on in the phenomenon called locative alternation.

Our focal example is spray. What has been overlooked in previous analyses is the fact that in a conventional spraying scene, one sends substance

in a mist back and forth, as in Figure 2.

As a result of this back and forth movement, the substance eventually

comes to cover a large portion of the surface to which it has been applied.

So a spraying scene is described as in Figure 3, where a double-sided arrow indicates a back and forth movement of a substance’s application.3

Notice that this spraying scene can receive two alternate interpretations. If we focus upon the paint, we get an event of sending a substance

in a mist. Hence the locative variant of spray as in Figure 4.

Figure 2. Movements during conventional spraying scene

spraying scene

Figure 3. Substance’s application during spraying scene

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

362

S. Iwata

spray paint onto the wall:

‘To send a liquid in a mist or fine droplets’

Figure 4. Interpretation of spraying scene with focus on the substance

spray the wall with paint:

‘To cover a surface with an even coat of deposited liquid adhering to it’

Figure 5. Interpretation of spraying scene with focus on the wall

If, on the other hand, we focus upon the wall, this is an event of covering the wall with paint. Accordingly, spray ends up in the [NP V NP with

NP] frame, parallel to cover, as in Figure 5.

Thus the ability of spray to alternate stems from the fact that a spraying scene can be construed either as moving paint onto the wall or as covering the wall with paint.

This view of the locative alternation reveals a crucial distinction between spray on the one hand, and spray paint onto the wall or spray the

wall with paint on the other. The meaning of spray is all that is enclosed

at the top in Figure 4 or Figure 5. That is to say, spray means to send a

liquid in a mist or fine droplets AND to cover a surface with an even coat

of deposited liquid adhering to it. By contrast, spray paint onto the wall or

spray the wall with paint means a construal of this scene either as a sending activity or as a covering activity. Let us call the meaning of the former Lexical Head Level Meaning, or L-Meaning, and that of the latter

Phrase Level Meaning, or P-Meaning. When that part of the L-meaning

compatible with a thematic core is profiled (Langacker 1987, 1991) with

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

363

the rest of the L-meaning backgrounded, a lexical verb occurs in a relevant syntactic frame. The locative alternation arises when the L-meaning

may yield more than one P-meaning.

3.2.

Form-meaning correlations

Next, we need a mechanism that ensures the form-meaning correspondences of the two variants. Despite the problems noted above, Pinker advances a well-worked out model of linking. Rather than directly relating

individual verbs to syntactic frames, Pinker argues that form-meaning

correspondence is mediated by thematic cores, where a thematic core is

‘a schematization of a type of event or relationship that lies at the core

of the meanings of a class of possible verbs’ (Pinker 1989: 73). Thus thematic cores like X acts upon Y, X causes Y to have Z, etc. are related to

syntactic frames like [NP V NP], [NP V NP NP], etc. This means that a

verb appears in a particular syntactic frame if its meaning is compatible

with a thematic core associated with that syntactic frame.

Clearly this linking mechanism is appropriate for the task at hand, so

that the next thing to do is to identify the thematic cores associated with

the locative variant syntax and the with variant syntax. What is crucial in

this connection is the observation commonly made in the literature (Croft

1991; Langacker 1987; Rice 1987, among others) that the entity which

can appear in direct object position is that to which a force is transmitted

in a causal chain. This is confirmed by the ‘‘What X did to Y’’ test,

which, though often employed as a diagnostic for a¤ectedness (Jackendo¤ 1990), actually identifies a ‘‘force recipient’’ as Rappaport and Levin

(2001) convincingly argue. Thus with pour-class verbs the locatum argument is acted upon, while with cover-class verbs the location argument is

acted upon, as in (17) and (18).

(17)

(18)

a.

b.

a.

b.

What she did to the water was pour it into the glass.

?What she did to the glass was pour water into it.

??What she did to the rug was cover the floor with it.

What she did to the floor was cover it with a rug.

With locative alternation verbs the acted upon entity alternates between

the two variants, as shown in (19) and (20).

(19)

(20)

a.

b.

a.

b.

What Bill did to the paint was smear it on the wall.

?What Bill did to the wall was smear paint on it.

?*What Bill did to the paint was smear the wall with it.

What Bill did to the wall was smear it with paint. (Jackendo¤

1990: 130)

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

364

S. Iwata

X acts upon Y

X acts upon Y, thereby

X acts upon Y by exerting force horizon-

causing Y to go Z

tally over the surface of Y with Z

Figure 6. Two subtypes of ‘‘X acts upon Y’’

Thematic core:

X acts upon Y, thereby

causing Y to go Z

syntactic frame:

X acts upon Y by exerting force horizontally over the surface of Y with Z

NP V NP directional PP

NP V NP with NP

(a)

(b)

Figure 7. Form-meaning pairings

L-meaning:

P-meaning:

spray1

‘To send a liquid in a mist or fine droplets’

thematic core:

X acts upon Y, thereby causing Y to go Z

syntactic frame:

NP V NP directional PP

Figure 8. Form-meaning paring for spray1

It seems reasonable to suppose, then, that the two thematic cores

associated with locative variant syntax and with variant syntax are two

subtypes of ‘‘X acts upon Y’’ as in Figure 6. The schematic meaning extracted from pour-class verbs (dribble, drip, drizzle, dump, ladle, pour,

shake, slop, slosh, spill ) can be phrased as ‘‘X acts upon Y, thereby causing Y to go Z’’.

(21)

a.

b.

She poured water into the glass.

*She poured the glass with water.

On the other hand, that for cover-class verbs (deluge, douse, flood, inundate, bandage, blanket, coat, cover, encrust, face, inlay, pad, pave, plate,

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

365

L-meaning:

P-meaning:

spray2

‘To cover a surface with an even coat of deposited liquid adhering to it’

Thematic core:

X acts upon Y by exerting force horizontally over the surface of Y with Z

syntactic frame:

NP V NP with NP

Figure 9. Form-meaning pairing for spray2

shroud, smother, tile) may be phrased as ‘‘X acts upon Y by exerting force

horizontally over the surface of Y with Z’’.

(22)

a.

b.

*She covered a rug over the floor.

She covered the floor with a rug.

We now have two form-meaning pairings that are responsible for the

linking of pour-class verbs and cover-class verbs, as shown in Figure 7.4

Accordingly, the two variants of spray are accounted for as in Figures

8 and 9.

3.3.

Six classes

Pinker (1989: 126–127) observes that the locative alternation verbs fall

into the following six classes:

i.

Spray-class: Force is imparted to a mass, causing ballistic motion in

a specified spatial distribution along a trajectory: drizzle, shower,

spatter, splash, splatter, spray, sprinkle, squirt

ii. Smear-class: Simultaneous forceful contact and motion of a mass

against a surface: brush, dab, daub, drape, dust, hang, plaster, settle,

slather, smear, smudge, streak, swab

iii. Scatter-class: Mass is caused to move in a widespread or nondirected

distribution: plant, scatter, seed, sew, sow, strew

iv. Pile-class: Vertical arrangement on a horizontal surface: heap, pile,

stack

v. Cram-class: A mass is forced into a container against the limit of its

capacity: cram, crowd, jam, stu¤, wad

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

366

S. Iwata

Figure 10. Movements during conventional smearing scene

Figure 11. Substance’s application during conventional smearing scene

smear paint on the wall

Figure 12. Interpretation of smearing scene with focus on the substance

vi.

Load-class: A mass of a size, shape, or type defined by the intended

use of a container is put into the container, enabling it to accomplish

its function: load, pack, stock

Not only is my account valid for spray-class verbs; it naturally extends

to other classes as well. Thus smear also involves the back and forth

movement of strokes over a surface, as shown in Figure 10.

(23)

a.

b.

smear paint on the wall

smear the wall with paint

Accordingly, the smearing scene is described as in Figure 11.

If we focus upon the locatum of this scene, we get the locative variant

as in Figure 12. If, on the other hand, we focus upon the location, we obtain the with variant as in Figure 13.

Similarly, with scatter-class verbs mass is caused to move in a widespread or nondirected distribution, so that the relevant scene can be construed either as a covering activity or as a pouring activity.

(24)

a.

b.

The farmer scattered seeds in the field.

The farmer scattered the field with seeds.

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

367

smear the wall with paint

Figure 13. Interpretation of smearing scene with focus on the location

piling scene

Figure 14. Conventional piling scene

With pile-class verbs the objects are arranged vertically, rather than

horizontally over a surface. But since the objects thus arranged come to

occupy a large portion of the relevant surface, it is not unreasonable to

suppose that the with variant of this class is also licensed as a covering

activity.

(25)

a.

b.

pile books onto the shelf

pile the shelf with books

The remaining two classes involve putting something into a container.

With cram-class verbs mass is forced into a container against the limit of

its capacity. So the container becomes fully occupied, and its inside, rather

than the surface, is acted upon.

(26)

a.

b.

cram food into the freezer

cram the freezer with food

With load-class verbs a kind of contents specific to a container are put

into the container, which enables the container to act in a designated way

(e.g., load a camera, load a gun).

(27)

(28)

a.

b.

a.

b.

load hay onto the truck

load the truck with hay

pack shirts into the suitcase

pack the suitcase with shirts

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

368

S. Iwata

loading scene

Figure 15. Conventional loading scene

X acts upon Y by exerting force to a significantly large portion of Y

[cover-type]

1. spray

2. smear

[overfilling]

3. scatter

4. pile

5. cram

[insertion]

6. load

Figure 16. Schematic meaning of the with variant syntax of spray, smear, scatter, pile,

cram, load

Unlike the cram-class, load-class verbs do not necessarily literally ‘fill’ the

container (Je¤ries and Willis 1984). Still, a significant portion of the container is occupied, and the container can be regarded as being thereby

acted upon.

Of the six classes, the first three (spray, smear, and scatter) clearly involve covering a surface. The fourth class, i.e. the pile-class, can also be

put into this category. The cram-class and the load-class involve occupying a significantly large portion of the container. Accordingly, by abstracting away from the dimensionality of the location entity, the schematic meaning that can be extracted from the with variants of these six

classes may be phrased ‘‘X acts upon Y by exerting force to a significantly

large portion of Y’’ as in Figure 16. This is the thematic core associated

with the with variant syntax.

Pinker (1989) and Gropen, Pinker, Hollander, and Goldberg (1991) describe these six classes, but they fail to notice that these six classes enter

into the alternation precisely because they have either a ‘covering’ semantics or a related meaning, in addition to a ‘putting’ semantics.

4.

4.1.

The di¤erences from lexical rule approaches

Derivation vs. non-derivation

Let us now compare my account with the previous analyses reviewed in

section 1. Pinker’s analysis as summarized in Figure 17 and my account

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

Verbs:

Thematic cores:

Syntactic frame:

‘spray1’

lexical rule

369

‘spray2’

substance moves in

surface is covered with

a mist

drops by moving mist

Move substance in a

Affect object in a

particular manner to

particular way by adding

an object

substance

V NP into/onto NP

V NP with NP

Figure 17. Lexical rule approach (adapted from Pinker 1989: 80)

L-meaning:

substance moves in a mist, and as a result the surface is

covered with drops by moving mist

P-meaning

Thematic cores:

‘spray1’

‘spray2’

substance moves in

surface is covered with

a mist

drops by moving mist

X acts upon Y, thereby

X acts upon Y by exerting

causing Y to go Z

force over the surface of

Y with Z

Syntactic frame:

NP V NP directional PP

NP V NP with NP

Figure 18. The L-meaning/P-meaning model

as in Figure 18 di¤er in two major points: the L-meaning/P-meaning distinction and the thematic core accorded to a with variant. In the ensuing

discussion, I will (almost exclusively) focus upon the first point, as this

will reveal a fundamental flaw in lexical rule approaches in general (see

Iwata 2002b for discussion on the second point).

As seen in Figure 17, Pinker derives spray the wall with paint from

spray paint onto the wall, not from spray. Similarly, Rappaport and Levin

(1988) derive load the truck with hay from load hay onto the truck, not

from load, as seen in 1.1. That is to say, they attempt to derive one Pmeaning from another, although what is actually going on is that a single

L-meaning gives rise to two P-meanings, an entirely di¤erent matter.

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

370

S. Iwata

(29)

a.

my account

L-meaning

b.

lexical rule approach

sense1

P-meaning1 P-meaning2

(P-meaning1 )

)

sense2

(P-meaning2 )

Interestingly enough, Pinker says much the same:

Basically, it is a gestalt shift: one can interpret loading as moving a theme (e.g.,

hay) to a location (e.g., a wagon), but one can also interpret the same act in terms

of changing the state of a theme (the wagon), in this case from empty to full, by

means of moving something (the hay) into it. (Pinker 1989: 79)

If we substitute an L-meaning for the scene and P-meanings for two interpretations, then the above remarks make perfect sense; in the passage

‘‘one can interpret loading as’’ Pinker speaks of ‘‘loading’’, not of ‘‘loading hay onto the wagon’’. Also, in the passage ‘‘one can also interpret the

same act’’, ‘‘the same act’’ refers to the act of ‘‘loading’’, not of ‘‘loading

hay onto the wagon’’. Thus the L-meaning/P-meaning distinction is recognized, albeit implicitly. Consider further the following: ‘‘The constraints or criteria governing the locative alternation stem, to a first approximation, from the ability of a predicate to support this gestalt shift’’

(Pinker 1989: 79). Here ‘‘the ability of a predicate to support this gestalt

shift’’ is another way of saying that the predicate has a meaning potential

to be interpreted in two ways.

Pinker rightly recognizes locative alternation as a gestalt shift, but he is

mistaken in implementing this idea by means of a lexical extension. The

significance of this point is further appreciated by noting that a gestalt

shift means that objectively the same scene is open to two di¤erent interpretations. Recall celebrated examples of gestalt shift like ‘Rubin’s vase’

or ‘duck-rabbit’. In all of these cases, one and the same environmental input may receive two di¤erent interpretations.

environmental input

interpretation 1

interpretation 2

a vase

two faces

a duck

a rabbit

(30)

A gestalt shift does not in any way derive one of the interpretations from

the other.

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

4.2.

371

An overall picture

The idea that a single L-meaning gives rise to two P-meanings is not new,

although not phrased exactly this way in the literature. Essentially the

same idea is to be found in Langacker (1987) and Goldberg (1995), whose

key terms find place in my account as in Figure 19.

Syntactic frames are associated with identifiable meanings, and this

pairing of form and meaning amounts to ‘construction’ in the sense of

Goldberg (1995). A verb can appear in a syntactic frame when its Lmeaning is compatible with the semantics of a construction. The verb

spray, whose L-meaning includes both ‘putting’ and ‘covering’, is thus capable of taking both into/onto and with forms. Which syntactic frame is

chosen is determined by which aspect of the L-meaning is profiled, this

process being a gestalt shift or ‘alternate construal of the same situation’

in the sense of Langacker (1987).

On my account, the locative alternation verbs are no di¤erent from

non-alternating verbs in their basic form-meaning correspondences. As

pointed out in 2.2., there are both a class of verbs that occur only as a

locative variant (e.g., pour) and a class of verbs that occur only as a with

variant (e.g., cover). The two classes are distinguished by the di¤erence in

their L-meanings. The L-meaning of pour, which specifies pure manner of

motion, only gives rise to a P-meaning associated with the into/onto form

(locative variant). By contrast, the L-meaning of cover gives rise to a Pmeaning associated with the with form (with variant) alone. Thus the possibility of alternation is entirely attributed to individual L-meanings.

Furthermore, this account has the advantage of circumventing the

problem posed by one of the putative derivations. As seen in section

1, neither Rappaport and Levin (1988) nor Pinker (1989) can o¤er a

L-meaning

alternate construal/

Gestalt shift

P-meaning

X acts upon Y, thereby

causing Y to go Z

P-meaning

X acts upon Y by exerting

force to a significantly large

portion of Y with Z

V NP directional PP

construction

V NP with NP

Figure 19. The L-meaning/P-meaning model and key terms in other theories

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

372

S. Iwata

plausible account of the derivation from the with variant. But since locative alternation is not a matter of deriving one variant from the other, no

lexical rules are needed in my account.5

4.3.

Application

The L-Meaning/P-Meaning distinction allows one to straightforwardly

account for the alternations of wrap and hit, which have been shown in

1.2 to be problematic for the means extension analysis of Rappaport and

Levin (1988) and Pinker (1989).

4.3.1.

(31)

Wrap.

a.

b.

c.

The verb wrap has three variants as in (31).

He wrapped shiny paper around a present.

He wrapped a present with paper.

He wrapped a present in paper.

My account for the locative alternation is readily applicable here: The Lmeaning of wrap is compatible with the semantics of each of the three

constructions underlying their respective forms. The in form is found with

verbs like plant or sow.

(32)

a.

b.

The workers planted the trees in the garden.

The workers planted the garden with (*the) trees. (Fraser 1971:

605)

The around form is found with verbs like coil, spin, twirl, whirl, and wind.

(33)

a.

b.

He coiled the chain around the pole.

*He coiled the pole with the chain. (Pinker 1989: 126)

And, of course, verbs like cover typically employ the with form. Thus the

alternation is described as in Figure 20.

The L-meaning of wrap is to fold a flexible object around another object, with the result that the flexible object conforms to part of the shape

of the enfolded object along two or more orthogonal dimensions. When

we focus upon an object folded around another object (i.e., paper), wrap

takes the around form. If, on the other hand, we focus upon the present,

two possibilities emerge. It is possible to regard the present as being covered with paper. But it is also possible to regard the present as being put

into the folded paper, for the L-meaning of wrap specifies that the paper

is larger than the enfolded object such that the folded paper can be construed as a kind of container:

Thus it is not wrapping when one installs shelf paper cut to the exact

size of the shelf, but it can be called wrapping if the paper extends beyond

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

373

L-meaning of wrap

To put around a flexible object

To cover the surface

To put an object

extended in two dimensions

of an object

into a layerlike medium

X acts upon Y, thereby

X acts upon Y by exerting

X acts upon Y, thereby

causing Y to go Z

force horizontally over the

causing Y to be in Z

surface of Y with Z

NP V NP around NP

NP V NP with NP

NP V NP in NP

Figure 20. Alternate construal of wrap

the edges of the shelf and is bent around them (Pinker 1989: 127). Again,

therefore, it is precisely the L-meaning that allows wrap to appear in the

three syntactic frames.

4.3.2. Hit. Verbs of physical contact like hit alternate as in (34), like

locative alternation verbs. Pinker (1989: 105) points out that this alternation is contingent upon the verb meaning.

(34)

a.

b.

I hit the bat against the wall.

[cf. I hit the wall with the bat]

She bumped the glass against the table.

Bill slapped the towel against the sink.

*I cut the knife against the bread.

[cf. I cut the bread with the knife]

*He split the ax against the log.

*Phil shattered the hammer against the glass.

*I broke a spoon against the egg.

*I touched my hand against the cat.

*I kissed my lips against hers. (Pinker 1989: 105)

Pinker observes that verbs of motion followed by contact can alternate,

but not verbs of motion followed by contact and a specific e¤ect (a cut,

a break, a split) or verbs of contact without motion (touch, kiss). The

with form found with verbs of physical contact is not strictly the same as

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

374

S. Iwata

the with form found with locative alternation verbs: The with phrase

names an instrument, not the substance added. It seems that the thematic

core is simply ‘X acts upon Y’.

Apart from this di¤erence, the alternation can be approached in a way

parallel to the locative alternation. Two constructions are at work here:

the ‘change of location’ sense in the against form and the ‘act upon’ sense

in the with form. Verbs of hitting, which specify both motion and contact

in their L-meanings, can fit into the semantics of either construction.

Consequently they can occur in either syntactic frame. By contrast, verbs

of breaking specify in their L-meanings a specific e¤ect, as well as motion

and contact, thus rendering the ‘act upon’ sense more salient. Consequently, they are compatible only with the semantics of ‘X acts upon Y’.

Verbs of touching simply lack the meaning component of change of location, so that they fit into only the semantics of ‘X acts upon Y’, too. This

supposition is confirmed by Dowty, who contrasts the classes of verbs

that take only the with form and those that take only the against form

(Dowty 1991: 596).

(35)

(36)

a. swat the boy with a stick

b. *swat the stick at/against the boy

Likewise: smack, wallop, swat, clobber, smite, etc.

a. *dash the wall with the water

b. dash the water against the wall

Likewise: throw, slam, bat, lob, loft, bounce, etc.

He further observes that verbs in (35) imply a pain-inflicting or punishing

action, but those in (36) are used only when the change of position of

the ball or projectile is important, not any e¤ect of the action upon the

location.

Thus the alternation hit enters into is described as in Figure 21.

L-meaning of hit

To attack

X acts upon Y

To move something against something else

X acts upon Y, thereby causing Y to go Z

NP V NP

NP V NP against NP

Figure 21. Alternate construal of hit

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

375

5. Means extension once again

While the means extension analysis of Rappaport and Levin (1988) and

Pinker (1989) is mistaken, it is nevertheless plausible at first sight. What

makes the means extension analysis look plausible? Furthermore, what

led both Rappaport and Levin and Pinker to adopt the means extension

analysis?

5.1.

Why means extension?

In the means extension analysis, the with variant subordinates the locative

variant. Rappaport and Levin (1988: 26) base this complex structure on

an entailment relation: Harry loaded the wagon with hay entails Harry

loaded hay onto the wagon, but not vice versa.

While the means extension analysis is one way to capture the entailment relation, it is not the only one. In my account, the two variants are

obtained by profiling a single scene di¤erently, depending upon whether

the locatum entity or the location entity is acted upon. What is crucial is

that one can mistakenly assume a temporal and causal order between the

two events thus obtained. Since our world knowledge tells us that one

first transfers bricks onto the truck, and then the truck becomes full, one

may be led to believe that the event denoted by the locative variant (i.e.,

transferring objects onto a container) temporally precedes that of the with

variant (i.e., the container being full), and that the latter cannot take

place without the former. Both Rappaport and Levin (1988) and Pinker

(1989) characterize the two variants in terms of the contrast between a

change of location and a change of state, and this characterization enhances this interpretation of the two variants, although the two events

are not strictly in a temporal/causal relation and their relation is one of

‘‘quasi-precedence’’ at best.6 This is the origin of the entailment relation

which Rappaport and Levin note.

The means extension analysis seems plausible, then, due to its similarity

to this quasi-precedence relation, which is intuitively applied between the

two variants. A means relation connects two distinct events, one of which

precedes the other both temporally and causally. With locative alternation verbs, the locatum being typically mass or multiplex entities, the activities denoted by the verbs tend to have some temporal duration: One

usually does not load the wagon with hay by transferring a load of hay

onto the wagon just once. Rather, repeated transferring activities are usually involved.7 Because of this temporal interval, the activity of transferring hay onto a wagon and that of filling the wagon are apparently temporally distinct from each other. By contrast, the activities of inscribing,

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

376

S. Iwata

presenting, and hitting do not take much time. For instance, since hitting

is a punctual action, it is rather di‰cult to regard hitting a stick against

the wall as being temporally distinct from hitting the wall with a stick.

This is why to say that loading the wagon with hay is brought about by

means of loading hay onto the wagon is more tolerable than to say that

hitting the wall with a stick is brought about by means of hitting a stick

against the wall.

5.2.

Why derive one from the other?

Why does Pinker formalize the locative alternation gestalt shift as a lexical derivation? First, Pinker assumes that semantic structures as employed in the generative lexical semantics literature are the only syntactically relevant aspects of meaning; thus, he ignores L-meanings, which fall

outside the realm of semantic structures. I argue, however, that Pinkerstyle semantic structures may well serve to capture P-meanings but not

L-meanings. Second, lexical items are natural sense categories and like

other such categories they are frequently (but mistakenly) represented by

members or subcategories, particularly by prototypical members, as Lako¤ (1987: 84) demonstrates in his discussion of a metonymic model. Since

P-meanings stand in a member-category relationship to their respective Lmeanings as shown in Figure 22, it is easy to confuse loading hay onto the

wagon, a member of the category load, with the category itself.8 This category error is partly understandable in that the verb load almost never appears without phrasal complements.

Pinker does not question the assumption that a relationship between

two variants implies that one is derived from the other. This assumption

in turn finds its roots in the classical notion of categorization that category members all share a ‘core’ of properties:9

classical categorization: All the entities that have a given property or collection of properties in common form a category. (Lako¤ 1987: 161)

Load

P-meaning2

P-meaning1

…

Figure 22. Load as a category

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

377

If one of the category members is taken as the core meaning itself, the

only relation that can hold between that variant and all others is a derivational one. The underlying logic is as follows: There are two variants of

load. The only way to relate them is to derive one from the other. Therefore, there must be lexical rules that do so. Yet as we have seen, relationships between variants need not depend upon one variant’s derivation

from another; instead, they may all derive from a common base.10

6. Constructional approach

So far I have contrasted my account with lexical rule approaches, alluding to its a‰nity with the Construction Grammar approach of Goldberg

(1995). From now on, I will compare my account with Goldberg’s

approach, dwelling on both similarities and di¤erences between them.11

6.1.

Goldberg 1995

Goldberg (1995) argues that constructions are form-meaning correspondences which exist independently of particular verbs, carry meaning, and

specify the syntactic structure. In each construction, the constructional

meaning is integrated with the verb meaning. Take put as an example,

which is integrated with the caused-motion construction as in Figure 23.

cause-move 3cause goal theme4 is the semantics associated directly

with the construction, while put 3putter, put.place, puttee4 is that of the

verb. The semantic roles associated with the construction (¼ argument

roles) are fused with those associated with the verb (¼ participant roles).

Thus the three participant roles of put are put in a correspondence with

the argument roles, resulting in the composite fused structure.

Now, Goldberg argues that the locative alternation can be accounted

for by understanding ‘‘a single verb meaning to be able to fuse with two

distinct constructions, the caused-motion construction and a causative-

Sem

CAUSE-MOVE

PUT

Syn

V

<cause

goal

<putter,

SUBJ

put.place,

OBL

theme>

puttee >

OBJ

Figure 23. Constructional meaning is integrated with the verb meaning—example put (following Goldberg 1995)

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

378

S. Iwata

construction plus with-adjunct’’ (Goldberg 1995: 179). The fusion of argument roles and participant roles is regulated by the two principles:

i.

ii.

The Semantic Coherence Principle: Only roles which are semantically

compatible can be fused.

The Correspondence Principle: Each participant role that is lexically

profiled and expressed must be fused with a profiled argument role

of the construction. If a verb has three participant roles, then one of

them may be fused with a nonprofiled argument role of a construction (Goldberg 1995: 50).

Crucially, the Correspondence Principle dictates that profiled participant

roles are fused with profiled argument roles. The definition of profiling

goes as follows: All and only obligatorily expressed participant roles are

lexically profiled; all and only argument roles which are expressed as direct grammatical relations are constructionally profiled.12 Goldberg

(1995: 176–77) illustrates how the fusion works as follows. Verbs like

slather require all three participant roles to be expressed: Both full variants of the alternation are acceptable as in (37), and none of the verb’s

participant roles may be left unexpressed as in (38).

(37)

(38)

a.

b.

a.

b.

c.

Sam slathered shaving cream onto his face.

Sam slathered his face with shaving cream.

*Sam slathered shaving cream.

*Sam slathered his face.

*Shaving cream slathered onto his face.

Thus slather has the following lexical entry, where profiled roles are indicated by boldface.

(39)

slather 3slatherer, thick-mass, target4

Now both the caused-motion construction and the causative-plus-withadjunct construction allow all three roles to be expressed, so there is no

problem satisfying the constraint that profiled roles are obligatory. Since

there are three profiled participants, one may be fused with a nonprofiled

argument role, in accord with the Correspondence Principle. The fusion

of slather with the two constructions also meets the Semantic Coherence

Principle. The three participant roles are compatible with the causedmotion construction’s argument roles, in that the slatherer can be construed as a cause, the thick-mass as a type of theme since it undergoes a

change of location, and the target as a type of goal-path. They are compatible with the causative-plus-with-adjunct construction’s argument roles

as well, for the target can be construed as a type of patient. Goldberg

claims that slather is thus compatible with both of the two constructions.

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

6.2.

379

Similarities

My account and Goldberg’s constructional analysis have much in common. First and foremost, in Goldberg’s analysis the two variants are

claimed to come from a single verb meaning as in (40), entirely parallel

to my analysis.

(40)

load 3loader, container, loaded-theme4

load bricks onto the wagon

load the wagon with bricks

Therefore, Goldberg’s account does not su¤er from the number of problems facing lexical rule approaches. In fact, the parallelism between the

two accounts goes deeper than the treatment of one particular phenomenon (i.e., locative alternation). Although Figure 23 might seem di¤erent

from my model, they convey essentially the same idea, and it is possible

to translate one representation into the other. Figure 24 gives us an idea

of the correspondences between the elements in the two models.

The constructional meaning corresponds to the thematic core; the verb

meaning to the L-meaning; the syntactic level of grammatical functions to

the syntactic frame; and the fused composite structure to the P-meaning.

Another thing worth mentioning at this point is that both accounts

recognize the importance of frame semantic knowledge (Fillmore 1975,

1977, 1982). Goldberg argues that the verb meanings must be frame semantic meaning, i.e., they must include reference to a background frame

rich with world and cultural knowledge. Goldberg illustrates the necessity

of rich frame semantic knowledge with examples of caused-motion

construction.

L-meaning

PUT

< putter, put.place, puttee >

P-meaning

Thematic core

CAUSE-MOVE

Syntactic frame

SUBJ

OBL

<cause

goal

theme>

OBJ

Figure 24. Correspondences between models by Goldberg (1995) and Iwata

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

380

S. Iwata

(41)

a.

b.

c.

d.

Joe walked into the room with the help of a cane.

?Joe marched into the room with the help of a cane.

??Joe rolled into the room with the help of a cane.

*Joe careened into the room with the help of a cane. (Goldberg

1995: 30)

In order to predict the distinction between (41a) and (41d), for instance,

it is not enough to know that walk and careen are motion verbs with a

manner component. Rather, reference to the particulars of manner is

essential.

The same thing can be said of the L-meaning in my account. For instance, the L-meaning of spray specifies that a substance is moved in a

mist in the direction of a particular object, resulting in the substance’s being deposited on the object, while that of pour specifies merely that a substance is moved downward in a stream. Aspects of verb meaning like

these tend to be neglected and relegated to ‘pragmatics’ on the ground

that only the skeletal meanings like x act or x cause y to go are grammatically relevant (Pinker 1989) and such world knowledge is grammatically irrelevant. However, it is precisely these aspects of verb meaning

that explain why spray, but not pour, enters into locative alternation.

Thus all semantic knowledge associated with verbs must be recognized

in order to represent their grammar. It is true that frame semantic knowledge is di‰cult to concisely paraphrase, let alone formally represent. But

this di‰culty should not be an excuse for neglecting significant portions

of verb meaning.

One apparent di¤erence between my account and Goldberg’s concerns

the contribution of constructions. Goldberg’s Construction Grammar approach primarily aims to capture form-meaning correspondences that fall

outside of lexical encoding. For instance, consider (42).

(42)

a.

b.

Sally baked her a cake.

He wiped the crumbs o¤ the table.

In (42a), the sense of transfer and the syntactic frame [NP V NP NP] are

not lexically specified by bake, but contributed by the ditransitive construction. Similarly, in (42b) it is the caused-motion construction, not the

lexical entry of wipe, that defines the sense of motion and the associated

syntactic frame. Clearly, in these cases constructions provide syntactic

and semantic properties that are not lexically encoded in the verb.

By contrast, my account of locative alternation is concerned with what

has traditionally been called subcategorization frames and their semantics, i.e., syntactic and semantic information lexically encoded. Both putting and covering are directly encoded in the L-meaning of verbs that

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

381

enter into the alternation. Here constructions simply highlight aspects of

verb meaning that are already there.

But this just indicates that with the locative alternation the encoded

verb meaning matches the constructional meaning. My account naturally

extends to cases like (42) on the assumption that ‘‘all semantic knowledge

associated with verbs’’ must be recognized, as noted above. Boas (2000)

argues that in order to account for resultatives, it is necessary to admit

into verb meanings two types of frame semantic information. The first,

‘‘on-stage’’ information, includes information about the prototypical

participants in an event. This is the information generally regarded as encoded verb meanings, corresponding to my L-meaning. On the other

hand, ‘‘o¤-stage’’ information is the kind of world knowledge one is subconsciously aware of when encountering a word in discourse, but usually

does not bother to mention. Boas claims that what is attributed to construction in Goldberg’s account of resultatives is strictly due to the ‘‘o¤stage’’ information of the verb (Boas 2000: 284–85).

Following Boas’s conception of verb meanings, the scene of wipe can

be described as in Figure 25. The ‘‘on-stage’’ information of wipe specifies

surface contact alone, but the o¤-stage information tells us that the wiping activity is likely to lead to removing an entity from a location.

If the verbal scene is limited to the on-stage information, the verb is

compatible with the simple transitive construction as in Figure 26(a). But

constructions can impose their skeletal syntax and schematic semantics in

a top-down fashion, and in order to meet the demands of the constructional meaning, the verb’s frame semantic scene may be extended.13 The

extended wiping scene, including the o¤-stage information, matches the

caused-motion construction as in Figure 26b.

Once an extended semantic frame has been built, therefore, the system

works on the same principles as before.

To recapitulate, my account and Goldberg’s analysis are fundamentally the same: versions of Construction Grammar to be contrasted with

lexical rule approaches.14

on-stage

off-stage

information

information

Figure 25. On-stage and o¤-stage information of wipe

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

382

S. Iwata

To rub a surface

X acts upon Y

NP V NP

(a)

To remove something from a surface

X acts upon Y, thereby causing Y to go Z

NP V NP directional PP

(b)

Figure 26. Two versions of wipe

6.3.

Problems of Goldberg 1995

Despite the fundamental similarities, the two accounts crucially di¤er as

to (1) how to represent the verb meaning, and (2) how a verb and a construction are integrated. In my account, the verb meaning is a Fillmorean

scene, and the integration of a verb with a construction is simply based

upon semantic compatibility. On the other hand, Goldberg represents

the verb meaning as a list of participant roles, and the integration of a

verb with a construction is identified as the fusion of semantic roles,

which is regulated by the Semantic Coherence Principle and the Correspondence Principle.

Since both of the accounts acknowledge the necessity for semantic

compatibility between verbs and constructions, what di¤erentiates Goldberg’s theory from mine is that it is a Correspondence Principle-based

account, which makes use of lexical profiling (of participant roles) and

constructional profiling (of argument roles). Herein lie a number of problems, which will be taken up below.

6.3.1. Is the Correspondence Principle really necessary? First, it is questionable whether the Correspondence Principle plays as great a role in

integrating verbs with constructions as Goldberg’s presentation will have

us believe. Although which of the two principles is more essential is

not made explicit in Goldberg (1995), a close look at locative alternation

verbs like load suggests the primacy of the Semantic Coherence Principle

over the Correspondence Principle. But before showing this point, I need

to somewhat modify Goldberg’s representation for load. Goldberg says

that it is not clear whether all roles of load need be expressed. While

the loader and container roles are obligatory as in (44a) and (44b), the

loaded-theme role need not be overtly expressed as in (44c).

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

(43)

(44)

a.

b.

a.

b.

c.

383

She loaded the wagon with the hay.

She loaded the hay onto the wagon.

*The hay loaded onto the truck.

??Sam loaded the hay.

Sam loaded the truck.

Goldberg claims that the loaded-theme role is still profiled, but optionally

omissible if licensed by context to receive a definite interpretation. This is

indicated by square brackets.

(45)

load 3loader, container, [loaded-theme]4

However, it is not the theme role but the container role that can be

contextually deleted. While Goldberg marks (44b) with a question mark,

it is acceptable as an elliptical form of Sam loaded the hay onto the truck.

In contrast, (44c) does not sound elliptical. Pinker (1989) makes a similar

observation: ‘‘Thus He loaded the gun sounds like a complete thought; He

loaded the bullets is grammatical but feels like a truncated version of He

loaded the bullets into the gun’’ (Pinker 1989: 125). Accordingly, the container role should be put into square brackets and the theme role is not

profiled as in (46).

(46)

load 3loader, [container], loaded-theme4

Let us now consider how (46) interacts with the two principles to yield the

two variants in (47).

(47)

a.

b.

Sam loaded the hay [onto the truck].

Sam loaded the truck (with the hay).

Recall that the Correspondence Principle says that if a participant role is

profiled, then it should appear in a prominent position. If we adhered to

the Correspondence Principle rigidly, then we would expect the container

role of load to always map to direct object position. The with variant in

(46b) would be straightforwardly accounted for under this conception of

the Correspondence Principle. But the locative variant in (46a) would be

problematic, for now the two principles are in conflict: The Correspondence Principle would require the container role to appear in direct object

position, but the Semantic Coherence Principle would prevent the container role from being fused with the theme role of the caused motion

construction, since it is not the container but the loaded-theme that is in

motion. And the fact is that the Semantic Coherence Principle wins, resulting in the fusion of the loaded-theme role with the theme role of the

caused-motion construction. Given that the Semantic Coherence Principle takes precedence over the Correspondence Principle when they are in

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

384

S. Iwata

conflict, the latter can be said to play only a subsidiary role, to say the

least.15

6.4.

What does lexical profiling tell us?

Next, while Goldberg (1995: 176–79) attempts to show that her account

works well with all of the five subclasses of locative alternation verbs

shown below, a closer look reveals that these alternating verbs do not behave uniformly with respect to lexical profiling as defined by Goldberg.16

i.

Slather-class: Simultaneous forceful contact and motion of a mass

against a surface: slather, smear, brush, dab, daub, plaster, rub,

smear, smudge, spread, streak . . .

ii. Heap-class: Vertical arrangement on a horizontal surface: heap, pile,

stack . . .

iii. Spray-class: Force is imparted to a mass, causing ballistic motion in

a specified spatial distribution along a trajectory: spray, spatter,

splash, splatter, inject, sprinkle, squirt . . .

iv. Cram-class: A mass is forced into a container against the limit of its

capacity: cram, pack, crowd, jam, stu¤ . . .

v. Load-class: A mass of a size, shape, or type defined by the intended

use of a container (and not purely by its geometry) is put into the

container, enabling it to accomplish its function: load, pack (of suitcases), stock (of shelves) . . . (Goldberg 1995: 176)

Goldberg claims that verbs of the heap-class must have three profiled

participant roles as in (50), since none of the verb’s roles may be left unexpressed as in (49).

(48)

(49)

(50)

a. Pat heaped mash potatoes onto her plate.

b. Pat heaped her plate with mash potatoes.

a. *Pat heaped mash potatoes.

b. *Pat heaped her plate.

c. *The mash potatoes heaped onto her plate.

heap 3heaper, location, heaped-goods4

But pile, a member of the heap-class, allows the location role to be

omitted as in (52a), and therefore should have the lexical entry as in (53).

(51)

(52)

(53)

a. He piled the books onto the shelf.

b. He piled the shelf with the books.

a. He piled the books.

b. *He piled the shelf.

pile 3piler, location, piled-goods4

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

385

Similarly, verbs of the cram-class are claimed to have three profiled roles

as in (56), but stu¤, another member of this class, behaves di¤erently in

this regard as in (58).

(54)

(55)

(56)

(57)

(58)

(59)

a. Pat crammed pennies into the jar.

b. Pat crammed the jar with pennies.

a. *Pat crammed the pennies.

b. *Pat crammed the jar.

c. *The pennies crammed into the jar.

cram 3crammer, location, crammed4

a. He stu¤ed the breadcrumbs into the turkey.

b. He stu¤ed the turkey with the breadcrumbs.

a. *He stu¤ed the breadcrumbs.

b. He stu¤ed the turkey.

stu¤ 3stu¤er, container, stu¤ed-theme4

And as seen above, the entry of load should be (46), where two roles are

supposed to be lexically profiled. But pack, a member of the load-class,

allows two roles to be unexpressed as in (61), and therefore should have

only one profiled role as in (62).

(60)

(61)

(62)

a. John packed books into the box.

b. John packed the box with books.

a. John packed the books.

b. John packed the box.

pack 3packer, container, packed-theme4

In short, di¤erent alternating verbs behave di¤erently with respect to the

obligatoriness of an argument, which indicates that lexical profiling as defined by Goldberg has nothing to do with the possibility of locative alternation at all.

6.5.

The proliferation of lexical entries17

Goldberg assumes that verb meaning is defined against a frame semantic

scene, and states that ‘‘part of a verb’s frame semantics includes the delimitation of participant roles’’ (Goldberg 1995: 43). In her view, the basic

meaning of a verb consists in the number and type of participant roles in

the frame semantics associated with the verb, which are determined by interpreting the verb in gerundial form (‘‘No -ing occurred.’’) as follows.

(63)

a.

b.

No sneezing occurred.

(one-participant interpretation)

No rumbling occurred.

(one-participant [sound emission] interpretation)

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

386

S. Iwata

c.

d.

No hammering occurred.

(one-participant [sound emision] or two-participant [impact]

interpretation)

No giving occurred.

(three-participant interpretation) (Goldberg 1995: 43–44)

However, identifying verb meaning thus with a list of participant roles,

rather than directly with a scene, can lead to proliferating verb senses.

Thus ‘‘No hammering occurred’’ allows for both a one-participant (sound

emission) interpretation and a two-participant (impact) interpretation as

in (63c). We can ensure that there is only one verb hammer by understanding a hammering scene to be interpretable either way, but Goldberg’s method of representation forces her to posit two ‘‘basic meanings’’

for hammer. Goldberg states that ‘‘these polysemous senses can be explicitly related by appealing to the frame semantics associated with each of

them’’ (Goldberg 1995: 44). But her lists of participant roles alone tell us

nothing about the relatedness between the senses.

A similar problem crops up with lease and rent, both of which can occur with either the tenant or the landlord being in subject position.

(64)

a.

b.

(65)

a.

b.

Cecile leased the apartment from Ernest.

(tenant, property)

Ernest leased the apartment to Cecile.

(landlord, property)

Cecile rented the apartment from Ernest.

(tenant, property)

Ernest rented the apartment to Cecile.

(landlord, property)

It seems straightforward to capture the relatedness between the two variants by understanding a leasing scene or a renting scene to be open to two

alternate interpretations, parallel to locative alternation. In order to implement this idea in Goldberg’s theory, however, lease should have only

one profiled role, the property. And in actuality, lease cannot occur with

only the property role.

(66)

*The property leased.

Goldberg therefore concludes that it is necessary to posit two distinct

senses of the verb:

(67)

a.

b.

lease1 3tenant property landlord4

lease2 3tenant property landlord4 (Goldberg 1995: 56)

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

387

In other words, Goldberg is forced to posit two distinct senses for lease

and rent by her definition of lexical profiling alone. But what is the point

of proliferating verb senses by adhering to lexical profiling, which has

been shown above to have nothing to do with the possibility of argument

structure alternations?

7. Semantic compatibility between verb meaning and constructional

meaning

Conceivably, it is not Goldberg’s intent to create the impression that an

array of participant roles is all that is syntactically relevant. Rather, the

participant roles should be a shorthand way to capture the rich frame

semantics associated with the roles, for Goldberg explicitly claims that

‘the entirety of the frame semantic knowledge [associated with the verb]

must be recognized’ (Goldberg 1995: 30). But what Goldberg actually

does is simply to match argument roles with participant roles as detached from the scene in which they appear, thereby failing to notice

that spray enters into the alternation precisely because a spraying scene

can be construed either as a putting activity or as a covering activity.

This seriously downplays the semantic compatibility between verbs and

constructions.

In what follows, I will show that by paying close attention to the particulars of a scene, my analysis can give a coherent account of alternation

phenomena.

7.1.

Spray once again

My analysis of the locative alternation in section 3 started with a case

study of spray, which well illustrates that a given scene can be construed

either as a putting event or as a covering event. Interestingly enough, this

verb can also be used to illustrate the superiority of my analysis over a

Correspondence Principle-based account. Spray exhibits an intransitive

variant as in (68c), besides a locative variant in (68a) and a with variant

in (68b).

(68)

a.

b.

c.

Bob sprayed paint onto the wall.

Bob sprayed the wall with paint.

Water sprayed onto the lawn.

(locative variant)

(with variant)

(intransitive variant)

Within Goldberg’s framework, these three variants are accommodated

by assuming that the target and liquid roles, but not the sprayer role, are

profiled.

(69)

spray 3sprayer, target, liquid4

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

388

S. Iwata

Her account goes as follows:

The fact that the target can be construed as a type of patient, in that the entity

which is sprayed can be construed as totally a¤ected, allows spray’s roles to fuse

with the argument roles of the causative construction. In particular, spray is licensed to occur in the caused-motion construction since the sprayer can be construed as a cause, the liquid as a type of theme, and the target as a type of goalpath. Similarly, the fact that the agent is not obligatory (i.e., non-profiled) allows

spray to occur in the intransitive motion construction instantiated by (68c). (Goldberg 1995: 179)

We have already seen that both the locative and with variants can be accounted for by semantic compatibility between the spraying scene and

two constructions. My account naturally extends to the intransitive variant as well.

First, notice that the contrast between (68a) and (68c) has been extensively discussed in the literature under the heading of causative alternation (See Levin and Rappaport 1991, 1995; Kiparksy 1997; Maruta

1998; Matsumoto 2000; McKoon and Macfarland 2000 and references

cited therein). Very briefly, my account of causative alternation goes as

follows, parallel to that of locative alternation: A given verb may exhibit

both an intransitive and a transitive variant if its conventional scene can

be compatible with both a thematic core associated with an intransitive

syntax and a thematic core associated with a transitive syntax. In order for

this to be possible, a frame semantic scene associated with the verb must

be interpretable as consisting of a causative event and an internal event

such that the latter has a high degree of autonomy and can therefore be

conceived of on its own, independent of an external causer (Iwata 2002a).

Now some locative alternation verbs enter into causative alternation

(e.g., splash, spray), and some do not (e.g., smear, daub). What di¤erentiates the two types is whether the manner encoded by each verb specifies

the movement of the theme or pertains to the agent, as pointed out by

Hale and Keyser (1997, 1999). Thus the manner of spraying is the manner of a substance’s movement (i.e., going in a mist). It is therefore possible to conceive of this movement alone as a spontaneous event, as separate from an external causer. In contrast, the manner of smearing pertains

to the manual movement (i.e., manipulation of a brush back and forth) of

the person engaged in the act of smearing, so that it is not possible to conceive of a substance’s movement as unfolding on its own, independently

of a human causer.

(70)

a.

b.

*Mud smeared on the wall.

They smeared mud on the wall.

Brought to you by | University Library at Iupui

Authenticated | 172.16.1.226

Download Date | 8/2/12 9:43 PM

Locative alternation and two levels of verb meaning

389

Thus the intransitive variant of spray can be straightforwardly accounted

for without using the notion of lexical profiling in the sense of Goldberg.

Not only is the lexical profiling marking in (69) not necessary; it makes

a wrong prediction. Croft (1998: 43) observes that spray, along with a

couple of other locative alternation verbs, may also occur transitively

with the theme role as the direct object.

(71)

a.

b.

c.

The broken fire hydrant sprayed water all afternoon.

The mudpots spattered mud just as we arrived.

The guests scattered rice as the bride and groom left the

church.

This is a counter-example to the Correspondence Principle, in that the

profiled target role of spray does not map onto a profiled position in

(71a).18 What needs to be noted, however, is that in (71a) spray is construed as a substance emission verb and thereby acquires the syntax of a

simple transitive construction, parallel to emit. According to Croft, (71a)