THE MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL

EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

THE UZBEK STATE WORLD LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY

ENGLISH Y FACULTY II

ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY DEPARTMENT

COURSE PAPER

Affixation as a major type of word

formation

Written by the student of the 3rd course, 312 group

Hoshimqulova M

Scientific superviser:

Azimbayeva D.A.

TASHKENT 2016

CONTENTS

Introduction……………………………………………………………….....…....3

Chapter I. The historical background of the English lexicology

1.1.Word-formation as a subject of study....................................................6

1.2.Various types and ways of Forming-words............................................8

Chapter II. Affixation as a productive type of word formation

2.1. Productivity of affixation………………………………………….................19

2.2. Structural and Semantic analysis of affixes……………………….…............31

Conclusion………………………………………………......................................40

The list of used literature…………………………………………………….....42

Introduction

As President Islam Karimov stated “Today the world demands that we

should say our word, demonstrate our intellectual capacities,”1 and that is why “The

most important thing for us is to give young people an opportunity to master a

certain speciality, to provide them with a reliable start in life”2.

Undoubtedly nowadays there are many opportunities for the youth of Uzbekistan to

show their full capacity in any field. Using these opportunities wisely, I am also

trying to research my bachelor diploma work in my speciality.

The given course paper is dedicated to the study of affixation as a productive way

of word-formation, which presents a certain interest both for theoretical

investigation and for the practical language use.

The aim of this course paper describes the main productive way of wordformation in Modern English according to this general aim there put forward the

following particular tasks:

1. to define word-formation as a subject;

2. to describe the various types and ways of forming words

3. to analyze the productive way of English word formation ;

4. to study the types of affixation

The theoretical significance of this course paper is that, the theoretical

position can be used in scientific works besides, that they may be used delivering

lectures on Lexicology. The practical value of the course paper is that, the practical

results and conclusion can be used in seminars on Lexicology.

The structure of this course paper is as follows: Introduction, main part,

four paragraphs conclusion and bibliography.

Introduction deals with the description of the structure of a course paper.

The first paragraph deals with word-formation as a subject.

The second paragraph deals with the types of forming words.

Islam Karimov (1998). Ideology – the Uniting Principle of Nation, Society and State. Answers to the questions of Editor-in-Chief of the

Taffakkur magazine. Tashkent: Uzbekistan. (p. 25)

2 The same book, (p. 21)

1

In the third paragraph we discuss about the productive ways of

word-formation. It consists of two paragraphs :

In the forth paragraph we discuss the Structural and Semantical analysis of affixes

and the types of affixation and its problem.

Introduction establishes the purpose, the tasks, novelty, the methods used in

the investigation, practical and theoretical significance of the work and explains

the reasons of choosing the theme for studying.

The list of used literature contains more then 20 units which deal with the

question under discussion.

Chapter I. The historical background of the English lexicology

1. 1. Word-formation as a Subject of Study

Before turning to the various processes of making words, it would be useful to

analyze the related problem of the composition of words of their constituent parts.

If viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units, which

are called morphemes. Morphs don't occur as free forms, but only as constituents

of words. Yet, they possess meanings of their own.

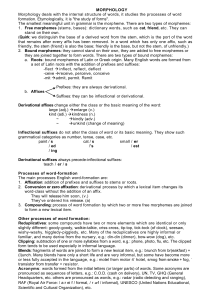

All morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots and affixes. The latter,

in their turn, fall into prefixes which precede the root in the structure of the word

(as in re - read, mis - pronounce, un - well) and suffixes which follow the root (as

in teach- er, cur - able, dec - ate).

Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called

derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word-building,

known as affixation (or derivation).

Derived words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary.

Successfully competing with this structural type is the, so-called, root word which

has only a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by a

great number of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier

borrowings (house, room, book, work, port,, street, table) and , in Modern English ,

has been greatly enlarged by the type oi word- building called conversion.

Another wide-spread word structure is a compound word consisting of two

or more stems (dining-room). Words of this structural type are produced by the

word-building process called composition.

The somewhat odd-looking words like flu, pram, lab, M.P., V-day, H-bomb

are called shortenings. Derivation and composition are the most productive ways

of word-building.

To return to the question posed by the title of this chapter, of how words are made,

let us try and get a more detailed picture of each of the major types of Modern

English word-building and, also, of some minor types.

Synchronic and Diachronic Approaches.

As a subject of study, word-building is that branch of Lexicology, which

studies the patterns on which a language, in this case the English language, builds

new words. It's self-evident that word-formation can deal only with words which

are analyzable both structurally and semantically. The study of the simple word

has no place in it. Therefore, writer, displease, atom- free and others are relevant to

word-formation, but to write, to please, atom, free are not.

Like any other linguistic phenomenon word-formation may be studied from

two angles - synchronically and diachronically. It's necessary to distinguish

between these two approaches, for synchronically the linguist investigates the

present-day system of the types of the word-formation while diachronically, he is

concerned with the history of word-building. To illustrate the difference of

approach we shall consider affixation.

Synchronically a derived word is structurally and semantically more complex

than a simple one, while diachronically it was formed from some other word. On

the synchronic plane a derived word is regarded as having a more complex

structure than its correlated simple word regardless of the fact whether it was

derived from a simple stem or not. There are cases in the history of the English

language when a word structurally more complex served as the original element

from which a simpler word was derived. Those are cases of the process called

back-formation (or back-derivation): beggar - to beg, editor - to edit, chauffeur - to

chauff and some others.

The fact that historically the verbs to beg, to chauff, to edit and others were

derived from the corresponding agent-nouns is of no synchronous relevance. For

the present day speaker no such relationship exists, therefore they are all simple

words in Modern English.

While analyzing and describing word-formation synchronically it's not

enough to extract the relevant structural elements from a word, describe its

structure in terms of morphemes and allomorphs and determine the type of wordformation; it is absolutely necessary to determine the position of the constituents

within the structural system of the language as a whole. Productivity of a

derivative type, therefore, can not be overlooked in this description.

Some of the ways of forming words in present-day English can be resorted

to for the creation of new words whenever occasion demands - these are called

productive ways of forming words ; other ways of forming words can not now

produce new words and these are commonly termed non-productive or

unproductive. For instance, affixation has been a productive way of forming words

ever since the Old English period fiscere1 and MnE striker and steamer. On the

other hand, sound-interchange must have been at one time a word-building means

but in Modern English it can't be used to coin new words. Actually, its function in

Modern English is only to distinguish one word from another, a verb from a noun,

as is the case with:

food - to feed, blood - to bleed, full - to fill and so on.

The delimitation between productive and non-productive ways and means of

word-formation as stated above is not, however, accepted by all linguists without

reserve.

Some linguists consider it necessary to define the term "productivity of a wordbuilding means" more accurately. They hold the view that productive ways and

means of word-formation are only those that can be used for the formation of an

unlimited number of new words in the Modern Language, such means that "know

no bounds" and easily form occasional words. This divergence of opinion is

responsible in particular, for the difference in the lists of derivational affixes

considered productive in various books on English Lexicology.

2.2. Various Types and Ways of Forming Words

The available linguistic literature on the subject cites various types and ways

of forming words. Books dealing with the problems of word-formation in the

Russian language, as well as some books on English Lexicology usually mention

morphologic, syntactic and semantic types of word-formation.

In conformity with the basic structural types of stems and words described

above the following two types of word

formation may be distinguished : word derivation and word-composition

(or compounding) words created by word-derivation have only one primary stem

and one derivational affix in terms of word-formation analysis, for example,

cleanness (from clean), to overestimate (from to estimate), chairmanship (from

chairman), waterproofness (from waterproof), openhandedness (from openhanded) etc. Some derived words have no affixes, because derivation is achieved

through conversion, for instance, to paper (from paper), a fall, and so on.

Words created by word-composition have at least two primary stems, e.g. ,

coal-black , ice-cold , looking-glass , daydream, hotbed, speedometer etc. Besides,

there are words built by a simultaneous application of composition and derivation

(suffixation or conversion) - derivational compounds, eg., long- legged, openminded, a breakdown and others.

The shortening of words stands apart from the above two-fold division of

word-formation. It can not be regarded as part of either word-derivation or wordcomposition for the simple reason that neither the root morpheme nor the

derivational affix can be singled out from the shortened word (lab, exam, V- day,)

Consequently, the shortening of words should be treated separately as a specific

type of word-formation.

Within the types, further distinction may be made between ways of forming

words, he basic ways of forming words in word- derivation, for instance, are

affixation and conversion. The lexicalization of grammatical forms, sound and

stress interchange and some others are usually referred to as minor ways of

forming words.

In describing the technique of word-formation it is important to point out the

means by which word-formation is effected. For instance, affixation is

characterized by the use of suffixes and prefixes, some cases of compounding by

the use of connecting elements etc.

Another classification of the types of word-formation worked out by

H.Marchand is also of interest. Proceeding from the distinction between complete

motivation as found in such composites as rain-bow, do-er, un-do and others are

partial motivation as exemplified by phonetic symbolism (pish, pooh, crack) he

considers two major groups:

1. Words formed as grammatical syntagmas, i.e. combination of full linguistic

signs;

2. Words which are not grammatical syntagmas, i.e. which are composites not

made up of full linguistic signs.

To the first group belong Compounding, Prefvcation, Derivation by a

Zero Morpheme and Back-derivation; To the second Expressive Symbolism,

Blending, Clipping, Rhyme and Abhut Gemination, Word-manufacturing.

There are two types of word-formation in Modern English: word -derivation and

word-composition. Within the types further distinction is made between the

various ways and means of word-formation.

Sound and stress-interchange in Modern English are means distinguished

between different words of different parts of speech.

The degrees of productivity and factors favoring it make an important aspect

of synchronic description of every derivational pattern within the two types of

word-formation.

Compound word is a productive way of Word-Formation

A compound word is a combination of two or more words that function as a

single unit of meaning. When two (or more) elements which could potentially be

used as stems are combined to form another stem, the form is said to be a

compound. A compound lexeme (or simply a compound) can thus be defined as a

lexeme containing two or more potential stems, Since each potential stem contains

at least one root, a compound must contain at least two roots.( If one of the

potential stems that makes up the compound is itself compound, the resultant form

may, of course, contain more than two roots, paint-box.)

However, this definition is not quite sufficient, since derivational process

may at times apply to forms containing more than one root (e.g. school-master,

super-highway). In such cases it is said that the base of the derivational process is

compound, but not that the whole lexeme is a compound. A compound may

therefore be more fully defined as a lexeme containing two or more potential stems

that has not subsequently been subjected to a derivational process. It should be

noted that while derivation may apply to forms containing more than one root, the

presence of two roots is not criteria for derivation as it is for compounding.

It is frequently useful to have a term to cover both the forms produced by

compounding to contrast these with forms produced by inflection and words which

are made up of just roots.

There are three types of compounds: those are written as single words, with no

hyphenation, are called closed compounds the word “flowerpot”, for example.

Hyphenated compounds, such as “merry-go-round” and “well-being”, are the

second type. Those in the third group, called open compounds, are written as

separate words – the nouns “school bus” and “decision making”.

Keep in mind that compounds can function as different parts of speech. In

such cases, the type of compound “carryover” as a noun and an adjective:

The money from that line item will carry over to next year`s budget.

The money we used for the trip was part of the carryover from last year`s

budget.

Carryover funds can be used to cover a deficit.

When you don`t know in which category a particular compound belongs, first

try looking it up in the dictionary. You will see there that some compounds are

hyphenated regardless of their function in a sentence. For example, “on-site” is a

hyphenated compound when it functions as an adjective or as an adverb: “The

team conducted on-site visits” and “The team conducted its review on-site”.

The real confusion begins when the compound is not given in the dictionary.

That is, it is a compound that is being formed for a very specific situation. In such

cases, we have rely on guidelines provide by the style manual to which we adhere.

Our style manual of choice, the Chicago Manual of Style, has a lengthy section

devoted to compound words- evidence that the rules are not simple.

One way to decide if a hyphen is necessary is to see if the phrase might be

ambiguous without it. For example, “large-print paper” might be unclear written as

“large print paper” because the reader might combine “print” and “paper” as a

single idea rather than combining “large” and “print”. Another such example is

“English-language learners”. Without the hyphens, a reader might think we are

talking about English people who are learning any language rather than people

who are learners of the English language.

On the other hand, no one is going to be confused by the phrase “chocolate

chip cookies” or “Saturday morning cartoons”. In other words, the open

compounds (i.e., no hyphen) “chocolate chip” and “Saturday morning” are so well

known that there is no room for ambiguity. The open compound “high school” is

so common, for another example, that we would not hyphenate the high phrase

“high school students”. We would, however, hyphenate “high risk” in phrase “high

risk students”.

The other time we must use hyphenation is to join a word to past participle to

create a single adjective preceding the noun it modifies: “a well-intentioned plan”,

or “a horseshoe-shaped bar”. Be aware, however, that we do not hyphenate these

same phrases when they follow the nouns they modify:

This is a government-mandated program.

The program is government mandated.

She is a well-respected student.

She is well respected as a teacher.

Another basic rule is that we never hyphenate compounds that are created with “ly” adverbs, even when they precede the nouns they modify: “a fully developed

plan”, or “a nationally certified teacher”. Here are more examples:

We sent heavily fortified troops.

The troops were heavily fortified.

All newly employed nurses must be evaluated regularly.

All the nurses on the eight floors are newly employed.

Compound words are two words put together. Knowing when to use a

hyphen and when to spell them as one word is difficult. British & U.S. usages do

not always agree, and different dictionaries published in the same country do not

always agree. In U.S. usage, fewer hyphens are than in British usage. Many more

compound words are written as one word today than were written that way in past.

Compound adjectives are two separate words that together modify a noun. They

are usually written with a hyphen if they come before the word they modify, but

sometimes usage changes and they become one word.

Written as

written with

written as two

One word

words

a hyphen separate

Firsthand

first-degree

first aid

Stream boat engine

post-Victorian

land office

Postgraduate meridium

post-mortem

stream

In English, words, particularly adjectives and nouns, are combined into

compound structures in a variety of ways. And once they are formed, they

sometimes metamorphose over time. A common pattern is that two words- fire fly,

say- will be joined by a hyphen for a time- fire-fly- and then be joined into one

word – firefly. In this respect, a language like German, in which words are happily

and immediately linked one to the other, might seem to have an advantage. There

is only one sure way to know how to spell compounds in English; use an

authoritative dictionary.

There are three forms of compound words:

1. the closed form, in which the words are melded together, such is firefly,

secondhand, softball, childlike, cross-town, redhead, keyboard, makeup, notebook;

2. the hyphenated form such is daughter-in-law, master-at-arms, over –the-counter,

six-pack, six-years-old, mass-produced;

3. the open form, such as post office, real estate, middle class, full moon, half sister

attorney general.

How are words modified by an adjective – “a little school.” “The yellow

butter”- is different from a compound word-“a high school”, “the peanut butter”- is

a nice and philosophical question. In clearly has something to do with the degree to

which preceding word changes the essential character of the noun, the degree to

which the modifier and the noun is separable. If you were diagramming a sentence

with a compound word, you would probably keep the words together, on the same

horizontal line.

Modifying compounds are often hyphenated to avoid confusion. The New

York Public Library`s Writers Guide points out than an old-furniture salesman

clearly deals in old furniture, but an old furniture salesman would be an old man.

We probably would not have the same ambiguity, however, about a car used

dealer. When compounded modifiers precede a noun, they are often hyphenated:

part-time teacher, fifty-yard wide field, fire-resistant curtains, and high –speed

chase. When those same modifying words came after the noun, however, they are

not hyphenated: a field fifty yard wide, curtains that are fire resistant, etc. the

second-rate

opera

company gave a

performance

that

was

first

rate.

Comparative and superlative forms of adjectives are hyphenated when

compounded with other modifiers: a highly rated bank, a partially refunded ticket,

publicly held securities. Sometimes hyphenated modifiers lost their hyphens when

they become compound nouns: A clear decision-making process was evident in

their decision making. The bluish was very slowly disappearing from the bluish

grey- sky. This is not always s, however: your high- rise apartment building is also

known as a high-rise.When modifying a person with his or her age, the

compounded phrase is hyphenated: my six-years-old son. However, when the age

comes after the person, we don`t use a hyphen. My son is six years old. He is,

however, a six-years-old.

Plurals and Possessives

Most dictionaries will give variant of compound plurals. When you have

more than one truck fuddled with sand, do you have several truck fuddled with

sand, do you have several truckfuls or trucksful? The dictionary will give you both,

with the first spelling usually preferred. (And the same is true of teaspoonfuls,

cupfuls, etc.) The dictionary will help you discover that only one spelling is

acceptable for some compounds –like passersby.

For hyphenated forms, the pluralizing –s is usually attached to the element

that is actually being pluralized: daughters-in-law, half-moons, mayors-elect. The

Chicago manual of Style says that “hyphenated and open compound are regularly

made plural by the addition of the plural inflection to the element that is subject to

the change in number” and gives as examples “father-in-law”, sergeants-in-arms”,

“doctors-in-arms”, “doctors of philosophy” and “courts martial”. The NYPL

Writer`s Guide puts this way: “the most significant word – generally the noun-

takes the plural form. The significant word may be at the beginning, middle, or end

of the term”. And then we get examples such as “attorney at law”, “bills of fare”,

“chiefs of staff”, “notaries public”, “assistant attorney general”, “higher ups”,

“also-rans”, and “go-between”.

As a general rule, then the plural form of an element in a hierarchical term belongs

to the base element in the term, regardless of the base element`s placement:

- first sergeant

- sergeants major

- sergeant first class

- colonel generals(Russian)

-

lieutenant generals

-

lieutenant colonels

-

apprentice Journeyman and master mechanics

- deputy librarians

- deputy assistant secretaries of state

The possessive of a hyphenated compound is created by attaching an apostrophe

–s to the end of the compound itself: my daughter-in-law`s car, a friend of mine`s

car. To create the possessive of pluralized and compounded forms, a writer is wise

to avoid the apostrophe –s form and use an “of phrase (the “post genitive”) instead:

the meeting of the daughter-in-law, the schedule of half-moons. Otherwise, the

possessive form becomes downright weird: the daughter-in-law`s meeting, friends

of mine`s cars.

One of the most difficult decisions to make about possessives and plurals of

compound words occurs when you can`t decide whether the first noun in

compound structure is acting as a noun that ought to be showing possession or as

what is called an attribute noun, essentially an adjective. In other words, do we

write that: I am going to writer`s conference or to a writers` conference? The

Chicago Style Manual suggests that if singular nouns can act as attributive nouns –

city government, tax relief – then plural nouns should be able to act as attributive

nouns: consumer group, teachers union. This principle is not universally endorsed,

however, and writers must remember to be consistent within a document.

The section doesn`t speak to the matter of compounded nouns as “Professor

Villa`s and Professor Darling`s classes have been filled.”

Compound nouns can be further subdivided into four groups according to

semantic criteria. Consider first the examples beehive, armchair, redskin,

highbrow, maidservant. These can all be divided into a second element, which is

the grammatical head (this is the element marked for number, and also, in

languages which have grammatical gender, the element which determines the

gender of the compound) and a first element which id the modifying element

(which is not marked for number and doesn`t determine gender). In the first two

examples, the compound is a hyponym of the grammatical head: a beehive is a

kind of hive; an armchair is a kind of chair.

This type of compound is termed an endocentric compound. In the second

two examples, the compound is not a hyponym of the grammatical head: a redskin

is not a type of skin, nor is a highbrow a type of brow.

This type of compound, termed an exocentric compound (or sometimes a

bahuvrihi compound, using the Sanskrit terminology), is a hyponym of some

unexpected semantic head (‘person ‘ in both the examples given here). Since the

semantic head is unexpressed in such compounds, the compound is frequently seen

as metaphorical or synecdoche.

Thirdly, maidservant is a hyponym of both maid and servant: a maidservant

is a type of maid and also a type of servant.

This type of compound is called an appositional compound.

The final division of compound nouns is exemplified by Alsace-Loraine

and Rank-Hives. Here is not always clear which element is the grammatical head

and the compound is not a hyponym of either element, but the elements name

separate entities which combine to form the entity denoted by the compound. This

type of compound is normally given the Sanskrit name of dvandva, although the

English term copulative is also used to describe them.

These semantic divisions interact with syntactic divisions according to the

form class of whole compound (compound noun, compound adjective, etc.) and

the form classes of the individual elements in the compounds, so that redskin, as

well as being an exocentric compound, is a compound noun made up of an

adjective and a noun, and armchair is an endocentric compound noun made up of

two nouns.

Chapter II. Affixation as a productive type of word formation

2.1. Productivity of affixation

Mastering the rules which native speakers intuitively apply to form new

terms and knowing which patterns of word formation show a higher productivity

will help learners to make generalisations and to understand at least a significant

part of newly formed terms.

One of the most productive word-formation processes in English is

affixation, a process by which a new word is built from a base, usually through the

addition of an affix, either at the beginning (prefix) or end of the base (suffix).

In classifying the prefixes and affixes the following approaches were used:

-

synchronic approach

-

diachronic approach

In our research we’ve studied the productivity of derivational process. The

topic of productivity has become one of much interest and debate. We took the

presence of neologisms to be evidence for the contemporary productivity of an

affix. For this purpose we mainly used the classification from OED (Oxford

English dictionary) and thus paid more attention on the dictionary-based method

(counting neologisms in a certain period of time by using the dictionary - OE

Morphological productivity

Morphological productivity can be defined as "the property of a given word

formation process to be used to derive a new word in a systematic fashion" (Plag

1999). With reference to Bauer (1983), "a morphological process can be said to be

more or less productive according to the number of new words which it is used to

form".

Most linguists consider the following major word-formational processes:

- Affixation

- Compounding

- Conversion

The minor word-formational processes are:

- Blending

- Clipping

- Back-formation

- Borrowing

- Reduplication

- Acronymy

- Sound interchange

Some of the ways of forming words in nowadays English can be restored to

for the creation of new words whenever the occasion demands – these are called

productive ways of forming words, other ways of forming words cannot now

produce new words, and these are commonly termed non-productive or

unproductive. R. S. Ginzburg gives the example of affixation having been a

productive way of forming new words ever since the Old English period. It follows

that productivity of word-building ways, individual derivational patterns and

derivational affixes is understood as their ability of making new words which all

who speak English find no difficulty in understanding.The delimitation between

productive and non-productive ways and means of word-formation as stated above

is not, however, accepted by all linguists without reserve. Some linguists consider

it necessary to define the term productivity of a word-building means more

accurately. They hold the view that productive ways and means of word-formation

are only those that can be used for the formation of an unlimited number of new

words in the modern language, i.e. such means that “know no bounds” and easily

form occasional words. This divergence of opinion is responsible for the difference

in the lists of derivational affixes considered productive in various books on

English lexicology. Nevertheless, recent investigations seem to prove that

productivity of derivational means is the highest. Moreover there are no absolutely

productive means; derivational patterns and derivational affixes possess different

degrees of productivity. Therefore it is important that conditions favouring

productivity and the degree if productivity of a particular pattern or affix should be

established. All derivational patterns experience both structural and semantic

constraints. The fewer are the constraints, the higher is the degree of productivity,

the greater is the number of new words built on it. The two general constraints

imposed on all derivational patterns are: the part of speech in which the pattern

functions and the meaning attached to it which conveys the regular semantic

correlation between the two classes of words. It follows that each part of speech is

characterized by a set of productive derivational patterns peculiar to it. Three

degrees of productivity are distinguished for derivational patterns and individual

derivational affixes: highly productive, productive or semi-productive and nonproductive.

Affixation is generally defined as the formation of words by adding derivational

affixes to different types of bases. Derived words formed by affixation may be the

result of one or several applications of word- formation rule and thus the stems of

words making up a word-cluster enter into derivational relations of different

degrees. The zero degree of derivation is ascribed to simple words, i.e. words

whose stem is homonymous with a word-form and often with a root-morpheme

(e.g. atom, haste, devote, anxious, horror, etc.). Derived words whose bases are

built on simple stems and thus are formed by the application of one derivational

affix are described as having the first degree of derivation (e.g. atomic, hasty,

devotion, etc.). Derived words formed by two consecutive stages of coining

possess the second degree of derivation (e.g. atomical, hastily, devotional, etc.),

and so forth.

Types of affixes

Affixes usually are divided into:

- prefixes

- suffixes

- infixes

Prefixes may be classified on different principles. Diachronically distinction is

made

between

prefixes

of

native

and

foreign

origin.

Synchronically prefixes may be classified:

1) According to the class of words they preferably form. Recent investigations

allow one to classify prefixes according to this principle.

It must be noted that most of the 51 prefixes of Modern English function in more

than one part of speech forming different structural and structural-semantic

patterns. A small group of 5 prefixes may be referred to exclusively verb-forming

(en–, be–, un–, etc.).

2) As to the type of lexical-grammatical character of the base they are added to

into: (a) deverbal, e.g. rewrite, outstay, overdo, etc.; (b) denominal, e.g. unbutton,

detrain, ex-president, etc. and (c) deadjectival, e.g. uneasy, biannual, etc. It is

interesting that the most productive prefixal pattern for adjectives is the one made

up of the prefix un– and the base built either on adjectival stems or present and

past participle, e.g. unknown, unsmiling, untold, etc.

3) Semantically prefixes fall into mono– and polysemantic.

4) As to the generic denotational meaning there are different groups that are

distinguished in linguistic literature: (a) negative prefixes such as un–, non–, in–,

dis–, a–, im–/in–/ir– (e.g. employment ( unemployment, politician ( non-politician,

correct ( incorrect, advantage ( disadvantage, moral ( amoral, legal ( illegal, etc.);

(b) reversative of privative prefixes, such as un–, de–, dis–, dis– (e.g. tie ( untie,

centralize ( decentralize, connect ( disconnect, etc.);

(c) pejorative prefixes, such as mis–, mal–, pseudo– (e.g. calculate ( miscalculate,

function ( malfunction, scientific ( pseudo-scientific, etc.); (d) prefixes of time and

order, such as fore–, pre–, post–, ex–(e.g. see ( foresee, war ( pre-war, Soviet (

post-Soviet, wife ( ex- wife, etc.); (e) prefix of repetition re– (e.g. do ( redo, type (

retype, etc.); (f) locative prefixes such as super–, sub–, inter–, trans– (e.g. market (

supermarket, culture ( subculture, national ( international, Atlantic ( trans-Atlantic,

etc.).

5) When viewed from the angle of their stylistic reference, English prefixes fall

into those characterized by neutral stylistic reference and those possessing quite a

definite stylistic value. As no exhaustive lexico-stylistic classification of English

prefixes has yet been suggested, a few examples can only be adduced here. There

is no doubt, for instance, that prefixes like un–, out–, over–, re–, under– and some

others can be qualified as neutral (e. g. unnatural, unlace, outgrow, override, redo,

underestimate, etc.). On the other hand, one can hardly fail to perceive the literarybookish character of such prefixes as pseudo–, super–, ultra–, uni–, bi– and some

others (e. g. pseudo-classical, superstructure, ultra-violence, unilateral, bifocal,

etc.).Sometimes one comes across pairs of prefixes one of which is neutral, the

other is stylistically coloured. One example will suffice here: the prefix over–

occurs in all functional styles, the prefix super– is peculiar to the style of scientific

prose.

6) Prefixes may be also classified as to the degree of productivity into highlyproductive, productive and non-productive. Suffixation is the formation of words

with the help of suffixes. Suffixes usually modify the lexical meaning of the base

and transfer words to a different part of speech. There are suffixes however, which

do not shift words from one part of speech into another; a suffix of this kind

usually transfers a word into a different semantic group, e. g. a concrete noun

becomes an abstract one, as is the case with child—childhood, friend—friendship,

etc. Chains of suffixes occurring in derived words having two and more suffixal

morphemes are sometimes referred to in lexicography as compound suffixes:

–ably = –able + –ly (e. g. profitably, unreasonably) –ical–ly = –ic + –al +

–ly (e. g. musically, critically); –ation = –ate + –ion (e. g. fascination, isolation)

and some others. Compound suffixes do not always present a mere succession of

two or more suffixes arising out of several consecutive stages of derivation. Some

of them acquire a new quality operating as a whole unit. Let us examine from this

point of view the suffix –ation in words like fascination, translation, adaptation and

the like. Adaptation looks at first sight like a parallel to fascination, translation.

The latter however are first-degree derivatives built with the suffix –ion on the

bases fascinate–, translate–. But there is no base adaptate–, only the shorter base

adapt–. Likewise damnation, condemnation, formation, information and many

others

are

not

matched

by

shorter

bases

ending

in

–ate, but only by still shorter ones damn–, condemn–, form–, inform–. Thus, the

suffix –ation is a specific suffix of a composite nature. It consists of two suffixes –

ate and –ion, but in many cases functions as a single unit in first-degree

derivatives. It is referred to in linguistic literature as a coalescent suffix or a group

suffix. Adaptation is then a derivative of the first degree of derivation built with

the coalescent suffix on the base adapt–.

Of interest is also the group-suffix –manship consisting of the suffixes

–man and –ship. It denotes a superior quality, ability of doing something to

perfection, e. g. authormanship, quotemanship, lipmanship, etc. It also seems

appropriate to make several remarks about the morphological changes that

sometimes accompany the process of combining derivational morphemes with

bases. Although this problem has been so far insufficiently investigated, some

observations have been made and some data collected. For instance, the nounforming suffix –ess for names of female beings brings about a certain change in the

phonetic shape of the correlative male noun provided the latter ends in –er, –or,

e.g. actress (actor), sculptress(sculptor), tigress (tiger), etc. It may be easily

observed that in such cases the sound is contracted in the feminine nouns.

Further, there are suffixes due to which the primary stress is shifted to the syllable

immediately preceding them, e.g. courageous (courage), stability (stable),

investigation (investigate), peculiarity (peculiar), etc. When added to a base having

the suffix –able/–ible as its component, the suffix –ity brings about a change in its

phonetic shape, namely the vowel is inserted between and e. g. possible possibility,

changeable ( changeability, etc. There are different classifications of suffixes in

linguistic literature, as suffixes may be divided into several groups according to

different principles:

1) The first principle of classification that, one might say, suggests itself is the part

of speech formed. Within the scope of the part-of- speech classification suffixes

naturally fall into several groups such as: a) noun-suffixes, i.e. those forming or

occurring in nouns, e. g.–er, –dom, –ness, –ation, etc. (teacher, Londoner, freedom,

brightness, justification, etc.); b) adjective-suffixes, i.e. those forming or occurring

in adjectives, e. g. –able, –less, –ful, –ic, –ous, etc.(agreeable, careless, doubtful,

poetic, courageous, etc.); c) verb-suffixes, i.e. those forming or occurring in verbs,

e. g.–en, –fy, –ize (darken, satisfy, harmonize, etc.); d) adverb-suffixes, i.e. those

forming or occurring in adverbs, e. g. –ly, –ward (quickly, eastward, etc.).

2) Suffixes may also be classified into various groups according to the lexicogrammatical character of the base the affix is usually added to. Proceeding from

this principle one may divide suffixes into: a) deverbal suffixes (those added to the

verbal base), e. g. –er,–ing, –ment, –able, etc. (speaker, reading, agreement,

suitable, etc.); b) denominal suffixes (those added to the noun base), e. g. –less,

–ish, –ful, –ist, –some, etc. (handless, childish, mouthful, violinist, troublesome,

etc.); c) de-adjectival suffixes (those affixed to the adjective base), e. g. –en, –ly, –

ish, –ness, etc. (blacken, slowly, reddish, brightness, etc.).

3) A classification of suffixes may also be based on the criterion of sense

expressed by a set of suffixes. Proceeding from this principle suffixes are classified

into various groups within the bounds of a certain part of speech. For instance,

noun-suffixes fall into those denoting: a) the agent of an action, e. g. –er, –ant

(baker, dancer, defendant, etc.); b) appurtenance, e. g. –an, –ian, –ese, etc.

(Arabian, Elizabethan,

Russian, Chinese, Japanese, etc.); c) collectivity, e. g. –age, –dom, –ery (–ry), etc.

(freightage, officialdom, peasantry, etc.); d) diminutiveness, e. g. –ie, –let, –ling,

etc. (birdie, girlie, cloudlet, squirreling, wolfing, etc.).

4) Still another classification of suffixes may be worked out if one examines them

from the angle of stylistic reference. Just like prefixes, suffixes are also

characterized by quite a definite stylistic reference falling into two basic classes: a)

those characterized by neutral stylistic reference such as

–able, –er, –ing, etc.; b) those having a certain stylistic value such as –old, –

i/form,–aceous, –tron, etc.

Suffixes with neutral stylistic reference may occur in words of different lexicostylistic layers. As for suffixes of the second class they are restricted in use to quite

definite lexico-stylistic layers of words, in particular to terms, e.g. rhomboid,

asteroid, cruciform, cyclotron, synchrophasotron, etc.

5) Suffixes are also classified as to the degree of their productivity.

Distinction is usually made between dead and living affixes. Dead affixes are

described as those which are no longer felt in Modern English as component parts

of words; they have so fused with the base of the word as to lose their

independence completely. It is only by special etymological analysis that they may

be singled out, e. g. –d in dead, seed, –le, –l,–el in bundle, sail, hovel; –ock in

hillock; –lock in wedlock; –t in flight, gift, height. It is quite clear that dead

suffixes are irrelevant to present-day English word-formation, they belong in its

diachronic study.

Living affixes may be easily singled out from a word, e. g. the noun- forming

suffixes –ness, –dom, –hood, –age, –ance, as in darkness, freedom, childhood,

marriage, assistance, etc. or the adjective-forming suffixes –en, –ous, –ive, –ful, –y

as in wooden, poisonous, active, hopeful, stony, etc.

However, not all living derivational affixes of Modern English possess the ability

to coin new words. Some of them may be employed to coin new words on the spur

of the moment, others cannot, so that they are different from the point of view of

their productivity. Accordingly they fall into two basic classes — productive and

non-productive word-building affixes.

It has been pointed out that linguists disagree as to what is meant by the

productivity of derivational affixes. Following the first approach all living affixes

should be considered productive in varying degrees from highly-productive (e. g. –

er, –ish,–less, re–, etc.) to non-productive (e. g. –ard, –cy, –ive, etc.).

Consequently it becomes important to describe the constraints imposed on and the

factors favouring the productivity of affixational patterns and individual affixes.

The degree of productivity of affixational patterns very much depends on the

structural, lexico-grammatical and semantic nature of bases and the meaning of the

affix. For instance, the analysis of the bases from which the suffix –ize can derive

verbs reveals that it is most productive with noun-stems, adjective-stems also

favour ifs productivity, whereas verb-stems and adverb-stems do not, e. g. criticize

(critic), organize (organ), itemize (item), mobilize (mobile), localize(local), etc.

Comparison of the semantic structure of a verb in –ize with that of the base it is

built on shows that the number of meanings of the stem usually exceeds that of the

verb and that its basic meaning favours the productivity of the suffix –ize to a

greater degree than its marginal meanings, e. g. to characterize — character, to

moralize — moral, to dramatize — drama, etc.

The treatment of certain affixes as non-productive naturally also depends on the

concept of productivity. The current definition of non-productive derivational

affixes as those which cannot hg used in Modern English for the coining of new

words is rather vague and maybe interpreted in different ways. Following the

definition the term non-productive refers only to the affixes unlikely to be used for

the formation of new words, e. g. –ous, –th, fore– and some others (famous, depth,

foresee).

If one accepts the other concept of productivity mentioned above, then nonproductive affixes must be defined as those that cannot be used for the formation

of occasional words and, consequently, such affixes as ; –dom, –ship, –ful, –en, –

ify, –ate and many others are to be regarded as non-productive.The theory of

relative productivity of derivational affixes is also corroborated by some other

observations made on English word-formation. For instance, different productive

affixes are found in different periods of the history of the language. It is extremely

significant, for example, that out of the seven verb-forming suffixes of the Old

English period only one has survived up to the present time with a very low degree

of productivity, namely the suffix –en (e. g. to soften, to darken, to whiten).

A derivational affix may become productive in just one meaning because that

meaning is specially needed by the community at a particular phase in its history.

This may be well illustrated by the prefix de– in the sense of ‘undo what has been

done, reverse an action or process’, e. g. deacidify (paint spray), decasualize (dock

labour), decentralize (government or management), deration (eggs and butter), de-

reserve (medical students), desegregate (coloured children), and so on.

Furthermore, there are cases when a derivational affix being nonproductive in the

non-specialized section of the vocabulary is used to coin scientific or technical

terms. This is the case, for instance, with the suffix –ance which has been used to

form some terms in Electrical Engineering, e. g. capacitance, impedance,

reactance. The same is true of the suffix –ity which has been used to form terms in

physics, and chemistry such as alkalinity, luminosity, emissivity and some others.

Measuring morphological productivity

There are basically two approaches to measure morphological productivity:

A dictionary-based method (counting neologisms in a certain period of time by

using a dictionary; e.g. you can count how many new English words ending in –ian

were formed in the 20th century)

A corpus-based method (finding words that occur only once in a large text corpus,

so-called hapax legomena; these hapaxes are an indicator of the word-building

power of an affix or another word-forming element).

We’ll focus our attention on the first method.

R. S. Ginzburg says that productivity of derivational patterns and affixes should

not be identified with the frequency of occurrence in speech, although there may

be some interrelation between them. Frequency of occurrence is characterized by

the fact that a great number of words containing a given derivational affix are often

used in speech, in particular in various texts. Productivity is characterized by the

ability of a given affix to make new words.

The dictionary-based method that is probably the most widely used and the

most widely rejected at the same time.

According to this measure, the productivity of an affix can be discerned by

counting the number of attested different words with that affix at a given point in

time. This has also been called the type-frequency of an affix.

The severe problem with this measure is that there can be many words with a given

affix, but nevertheless speakers will not use the suffix to make up new words. An

example of such a suffix is -ment, which in earlier centuries led to the coinage of

hundreds of then new words. Many of these are still in use, but today’s speakers

hardly ever employ -ment to create a new word and the suffix should therefore be

considered as rather unproductive (cf. Bauer 2001:196). Thus the sheer number of

types with a given affix does not tell us whether this figure reflects the productivity

of that affix in the past or its present potential to create new words.

Counting derivatives can nevertheless be a fruitful way of determining the

productivity of an affix, namely if one does not count all derivatives with a certain

affix in use at a given point in time, but only those derivatives that were newly

coined in a given period, the so-called neologisms. In doing this, one can show that

for instance an affix may have given rise to many neologisms in the 18th century

but not in the 20th century. The methodological problem with this measure is of

course to reliably determine the number of neologisms in a given period. For

students of English this problem is less severe because they are in the

advantageous position that there is a

dictionary like the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). This dictionary has about

500,000 entries and aims at giving thorough and complete information on all

words of the language and thus the development of the English vocabulary from its

earliest attestations onwards.

Affix

OED Neologisms

-able

185

-full (measure)

22

-full (property)

14

-ion

625

-ish

101

-ist

552

-ity

487

-ize

273

-less

103

-ness

279

-th

2

-ter

1

-wise

12

-er

312

To summarize our discussion of how productivity can be measured, it should have

become clear that the different measures have the great advantage that they make

certain intuitive aspects of morphological productivity explicit and calculable.

Furthermore, we have learned that productivity is largely a function of the

frequency of words and that the reason for the connection between frequency and

productivity lies in the nature of the storage and processing of (complex) words in

the lexicon.

2.2. Structural and Semantic analysis

The process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an

affix or several affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this

procedure is very important and, therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts

about the main types of affixes.

From the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same two

large groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some Native Suffixes.

-er worker, miner, teacher, painter . . .

-ness coldness, loneliness, loveliness . . .

-ing feeling, meaning, singing, reading . . .

-dom freedom, kingdom, wisdom . . .

-hood childhood, manhood, motherhood . . .

-ship friendship, mastership, companionship . . .

-ful careful, joyful, wonderful, sinful, skillful...

-less careless, sleepless, cloudless, senseless . . .

-y tidy, merry, snowy, showy . . .

-ish English, Spanish, reddish, childish . . .

-ly lonely, lovely, usly, likely, lordly . . .

-en wooden, woolen, silken, golden . . .

-some handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome . . .

-en widen, redden, darken, sadden . . .

-ly warmly, hardly, simply, carefully, coldly . . . .

Borrowed affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English

vocabulary. It would be wrong though, to suppose that affixes are borrowed in the

same way and for the same reasons as words. An affix of foreign origin can be

regarded as borrowed only after it has begun an independent and active in the

recipient language, that is, is taking part in the word- making processes of that

language. This can only occur when the total of words with this affix is so great in

the recipient language as to affect the native speakers subconscious to the extent

that they no longer realize its foreign flavor and accept it as their own.

Affixes can also be classified into productive and nonproductive types. By

productive affixes we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this

particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive

affixes is to look for them among neologisms and so-called nonse-words, words

coined and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually formed on

the level of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive patterns

in word-building. When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an

unputdownable thriller, we will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective

in dictionaries, for it is a nonse- word coined on the current pattern of Modern

English and is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming borrowed

suffix -able and the native prefix un- .

The adjective thinnish and baldish bring to mind dozens of other

adjectives made with the same suffix: oldish, youngish, mannis , girlish ,fattish,

longish, yellowish.

But dispectic - lookingish is the author's creation aimed at a humorous effect

and, at the same time, proving beyond doubt that the suffix -ish is a live and active

one.

The same is well-illustrated by the following popular statement: "I don`t like

Sunday evenings. I feel so Mondayish ". (Mondayish is certainly a nonce-word.)

One should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency of

occurance. There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless

, are no longer used in word-derivation.

Some Productive Affixes

Noun-forming suffixes

-er, -ing, -ness, -ism, -ist, -ance

Adjective-forming suffixes

-y, -ish, -ed, -able, -less...

Verb-forming suffixes

-ise/-ize, -ate...

Adverb-forming suffixes

-ly...

Prefixes

-un-, re-, dis-...

Some Non- Productive Affixes

Noun-forming suffixes

-th,-hood...

Adjective-forming suffixes

-ly,-some,-en,-ous...

Verb-formingsuffixes-en...

Affixation is generally defined as the formation of words by adding derivational

affixes to stems. On the morphemic level every word formed by means of

affixation has only one root- morpheme, which is its semantic center and one or

more derivational affixes to stems On the morphemic level every word formed by

means of affixation has only one root-morpheme, which is its semantic center and

one or more derivational affixes.

For instance , the words displease and realism have each only one root-morpheme

and one derivational affix - the prefix dis- and the suffix -ism , whereas the noun

reappearance consists of the prefix re- , the root-morpheme appear- and the suffix

- ance.

On the derivational level derived words comprise a primary stem (the stem

being in itself either a simple, a derived or a compound stem), friendliness = (noun

+ ly) + -ness (a derived stem), chairmanship = (noun + noun) +ship (a compound

stem). The stems of words making up a word-cluster enter into derivational

relations of different degrees. The zero degree of derivation is ascribed to simple

words, i.e. words whose stem is homonymous with a root-morpheme, e.g. atom,

haste , devote... Derived words whose stems consist of a root-morpheme and a

derivational affix are described as having the first degree of derivation , e.g. atomic

, hasty , devotion ... Derived words formed by two consecutive stages of coining

possess the second degree of derivation, e.g. atomic hasty, devotion...

The following diagram graphically represents the hierarchy of derivational

relations within a word-cluster, the indexes 0, 1, 2, etc. indicating the

corresponding degree of derivation:

In conformity with the division of derivational affixes into suffixes and

prefixes affixation is subdivided into suffixation and prefixation. Distinction is

naturally made between prefixal and suffixal derivatives: unjust, rearrange; justify,

arrangement.

Words like reappearance, unreasonable, denationalize are generally

qualified as prefixal-suffixal derivatives. The reader should clearly realize that this

qualification is relevant only in terms of the constituent morphemes such words are

made up of i.e. from the angle of morphemic analysis. From the point of view of

derivational analysis such words are mostly suffixal or prefixal derivatives e.g.

reappearance = (re + appear -) + -ance, unreasonable = un- + (reason- + -able),

denationalize = de- + (nation + ize) .A careful study of a great many suffixal and

prefixal derivatives has revealed an essential difference between them. In Modern

English suffixation is characteristic of noun and adjective formation, while

prefixation is typical of verb formation. As a general rule, prefixes modify the

lexical meaning of stem to which they are added. A prefixal derivative usually

joins the part of speech the unprefixed word belongs to e.g.

un - usual -cf. usual; indefinite -cf. definite; discomfort -cf. comfort etc.

In a suffixal derivative the suffix doesn't only modify the lexical meaning of

the stem it is affixed to, but the word itself is usually transferred to another part of

speech e.g.

care - less a - cf care n ; suit - able - a ; good - ness good. Furthermore, it's

necessary to point out that a suffix closely knit together with a stem forms a prefix

which is as a general rule, more independent semantically, reading - "the act of

one who reads " ; "ability to read" ; and to re-read - "to read again".

The origin of affixes.

Affixation is the formation of words with the help of derivational affixes.

Affixation is subdivided into prefixation and suffixation.

For instance, if a prefix "dis" is added to the stem "like" (dislike) or suffix

"ful" to "law" (lawful) we say a word is built by an affixation. Derivational

morphemes added before the stem of a word are called prefixes (e.g. un+like) and

the derivational morphemes added after the stem of the word are called suffixes

(hand+ful). Prefixes modify the lexical meaning of the stem meaning i.e. the

prefixed derivative mostly belongs to the same part of speech.

Examples include, like (v) - dislike (v); kind (adj) - unkind (adj), but suffixes

transfer words to different part of speech.

Another example, teach (v) - teacher (n). But new investigations into the

problem of prefixation in English showed interesting results. It appears that the

traditional opinion, current among linguists that prefixes modify only the lexical

meaning of words without changing the part of speech is not quite correct. In

English there are about 25 prefixes which can transfer words to a different part of

speech, such as , head (n) - behead (v), bus (n) - debus (v), brown (adj) - embrown

(v), title (n) - entitle (v),large (adj) - enlarge (v), camp (n) - encamp (v), war (n) prewar (v)...

If it is so we can say that there is no functional difference between suffixes and

prefixes. Besides, there are linguists who treat prefixes as a part of wordcomposition. They think that a prefix has the same function as the first component

of a compound word. Other linguists consider prefixes as derivational affixes

which differ essentially from root- morphemes and stems. From that point of view

of their origin affixes may be native and borrowed. The suffixes -ness, -ish , -dom ,

-ful, -less , -ship and prefixes be- , mis- , un- , fore- etc. are of native origin. They

came from the Greek, Latin and French language 3 . Many of suffixes and the

suffixes of native origin were independent words. In the course of time they have

lost their independence and turned into derivational affixes. For instance, -dom, hood "head-state " , rank, -dom (dom condemn), -ship has developed from noun

"scipe" (meaning:state); the adjective forming suffix -ly has developed from the

noun "lie" (body, shape). The prefixes out-, under- , over- and others have

developed out of independent words. Another problem of the study of affixes

homonymic affixes. Homonymic affixes are affixes which have the same sound

form, spelling but different meanings and they are added to different parts of

speech.

² Зягковский P.Т. "Суффиксальная система n современного Английском языке" Масква 1966,

Examples include, -ful(l) forms adjectives from a noun : love (v) - loveful

(adj) ; man (v) - manful (adj);

-ful(2) forms adjective from a verb : forget (v) - forgetful

(adj) ; thank (v) - thankful (adj).

-ly( 1) added to an adjective stem is homonymous to the

adjective forming suffix ;

-ly(2) which is added to a noun stem : quickly, slowly and lovely, friendly.

The verb suffix -en(l) is added to a noun and adjective stem is homonymous to the

adjective forming suffix;

-en(2) which is added to a noun stem:

Examples are to strengthen, to soften, to wooden, to golden. The prefix un- (1) is

added to a noun and a verb stem is homonymous to the prefix;

un- (2) which is added to an adjective stem, such as: unshoe, unbind, unfair,

untrue.

In the course of the history of the English as a result of borrowings there appeared

many synonymous affixes in the language , such as :the suffixes -er , -or , -ist, -ent,

-ant, -eer , -ian, -man , -ее , -ess form synonymous affixes denoting the meaning

"agent". Having the meaning of negation the prefixes un- , in-, non-, dis-, misform synonymic group of prefixes. If s interestng to point out that the synonymous

affixes help us to reveal, different lexico-semantic grouping of words.

For example, the words formed by the suffixes -man , -er , -or , -ion , -ее , -eer , ent, -ant and some others belong to

the lexico-semantic groupings of words denoting "doer of the action ".

The affixes may be undergo semantic changes, they may be polysemantic.

The noun forming suffix -er has the following meanings:

1)persons following some special trade and profession (,driver, teacher, hunter);

2)persons doing a certain action at the moment in question (packer, chooser ,

giver);

3)tools {blotter, atomizer, boiler , transmitter).

The adjective forming suffix " -y " also has several meanings:

1. composed of, full of (bony, stony)

2. characterized by (rainy, cloudy)

3. having the character of resembling what the stem denotes (inky, bushy).

Thus, affixes have different characteristic features. The Comparative analysis

of the English is not so rich in suffixes as, for example, the Uzbek language. The

total number of suffixes is 6 7 in English, but the Uzbek suffixes are 1713 and vice

versa, prefixation is more typical to the English language than Uzbek. In Uzbek

there are following prefixes: бе -, но-, ба-, бо-, ним- . By their origin the Uzbek

affixes like English ones are divided into native and borrowed.

The suffixes: -чи , -rap , -зор ,-ли , -лик , -ок are native suffixes , but: -изм ,

-ация , бо-, но-, нома-, -ки are of borrowed origin. The affixes may be divided

into different semantic groups. These semantic groups of affixes mat be different

in different languages. For example, diminutive affixes in Uzbek are more than in

English.

DIMINUTIVE

SUFFIXES

In English

-ie (birdie)

-let (cloudlet)

In Uzbek

-акай (йул-йулакай), -алак

(дунгалак)

-ling (wordling)

-жон (дадажон)

-ette (mountainette)

-кач (тахтакач)

-ock (hillock)

-у (Jony)

-кина (гудаккина)

-ой (Салимаой)

-et (whippet)

-ча (аравача)

-kin (tigerkin)

-чак (тугунчак)

As compared with the Uzbek language the native affixes are more widely used

in English.

In Uzbek : -сиз (кулсиз), бе- (берахм), но- (нохуш)

In English : -less , а- , an- (anomalous), un- (unkind), dis- (dislike), anti(antibiotic), de- (decode), in- (innocent), ir- (irregular), im- (impossible), non(nondeductive). Though the number of Uzbek prefixes are very few, they are

capable of changing words from one part of speech into another.

Here are given some examples: адаб (от) - боадаб (сифат),

хосил (от) - cерхосил (сифат),

илхом (от) - ноилхом (сифат),

бахт (от) - бебахт (сифат),

ранг (от) - нимранг (сифат).

Non-productive affixes are those which are not used to form new words in

Modern English.

For instance, -ard , -cy , -ive , -en , -dom , -ship , -ful, - en , -ify are not

productive suffixes ; in(i), ir(im), mis-, dis- are non-productive prefixes. These

affixes may occur in a great number of words but if they are not used to form new

words in Modern English, they are not productive.

Conclusion

Word-formation is the process of creating words from the material available in

the language after certain structural and semantic formulas and patterns.

As a subject of study, word-formation is that branch of Lexicology which studies

the patterns on which the English language builds words. Like another linguistic

phenomenon word-formation may be studied synchronically and diachronically.

There are two principal types of word-formation in Modern English: wordderivation and word-composition. Within the types further distinction is made

between various ways and means of word-formation.

Distinction is made by Productive and Non-Productive ways of word-formation.

In the practical analysis of derived words the following characteristics of

derivational affixes (suffixes and prefixes) should be pointed o u t :

1. The productivity of the affix (highly productive, semi- productive or nonproductive).

2. The part of speech the affix forms (nouns, adjectives, verbs etc.).

Affixation (prefixation and suffixation) is the formation of words by adding

derivational affixes to primary stems. One distinguishes between derived words of

different degrees of derivation.

Many of Modern English derivational affixes were at one time independent words.

Others have always been known as suffixes or prefixes within the history of the

English language.

As a summary to the study of affixation as a productive way of wordformation, which presents a certain interest both for theoretical investigation and

for the practical language use.

Word-formation is the process of creating words from the material

available in the language after certain structural and semantic formulas and

patterns.

As a subject of study, word-formation is that branch of Lexicology

which studies the patterns on which the English language builds words. Like

another

linguistic

phenomenon

word-formation

may

be

studied

synchronically and diachronically.

There are two principal types of word-formation in Modern English:

word-derivation and word-composition. Within the types further distinction

is made between various ways and means of word-formation.

Distinction is made by Productive and Non- Productive ways of

word-formation. In the practical analysis of derived words the following

characteristics of derivational affixes (suffixes and prefixes) should be

pointed out:

The first the productivity of the affix (highly productive, semiproductive or non-productive).

The second the part of speech the affix forms (nouns, adjectives, verbs etc.).

Affixation (prefixation and suffixation) is the formation of words by adding

derivational affixes to primary stems. One distinguishes between derived words of

different degrees of derivation.

Many of Modern English derivational affixes were at one time independent

words. Others have always been known as suffixes or prefixes within the history of

the English language.

The list of used literature

1. D.J.Buranov, A.Muminov “A practical course in English Lexicology",

Publishing house "O`qituvchi", 1990.

2. Ginzburg "A course in Modern Lexicology", Moscow High School, 1976.

3. AntrushinaG.B., Afanasyeva V.A."English Lexicology", Moscow High School,

1985.

4. Arbekova T.I. "English Lexicology", Moscow, 1977.

5. Каращук П.М. " Словообразование Аглийского языка", Moscow High

School, 1977.

6. Татаулин Р.Г. "Словообразованние и текст"-, Куйбишев , 1986.

7. Царев В.П. "Словообразованние и синтаксис", И.ЯШ., 1982.

8. Улуханов " Словообразовательного относиекич между частьями речи ", "

Вопросы языкознания " , 1979.

10. Зятковский Р.Т. "Суффиксальная система в современного Английском

языке'' Масква 1966,

11. Мешков " Словосложение в современном Английском языке Москва,

В.Ш., 1985;

12. Arnold "The English Word" , Moscow High School,1973

13. Aзнаурова Э.С. “Словообразование и текст”, Куйбишев, 1986

14. Adams V. Introduction into English Word formation. Lond. 1983

15. Potter S. Modern Linguistics. Lond. 1957.

16. Cannon G. Historical Changes and English Word formation: New Vocabulary

items. N.Y., 1986

17. Marchand, H. The categories and types of present day word-formation.

Harrassowitz. 1960.

Dictionaries:

Berg, P. A dictionary of new words in English. London. 1953.

Jones, D. An English pronouncing dictionary. London. 1957

The Oxford pocket Russian dictionary. Oxford. 1994