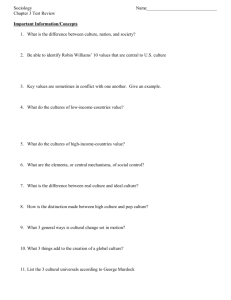

Culture: Definition, Material & Nonmaterial Aspects, Culture Shock

advertisement