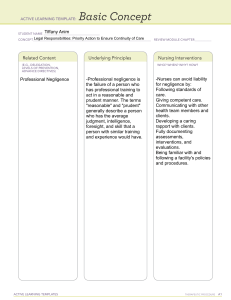

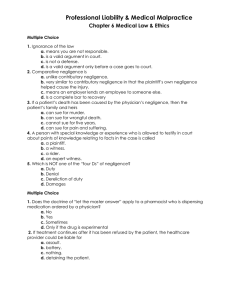

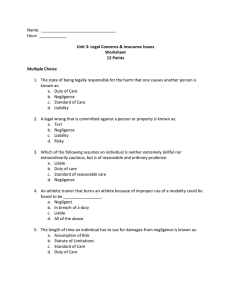

Torts & Damages: Conceptual Framework & Liabilities

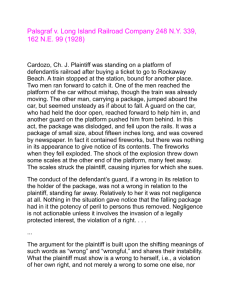

advertisement