Ethnic Identity & Consumer Ethnocentrism: Acculturation & Materialism

advertisement

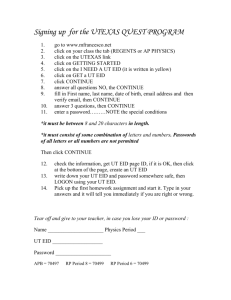

Research Article Ethnic Identity Impact on Consumers’ Ethnocentric Tendencies: The Moderating Role of Acculturation and Materialism Management and Labour Studies 45(1) 31–53, 2020 © 2019 XLRI Jamshedpur, School of Business Management & Human Resources Reprints and permissions: in.sagepub.com/journals-permissions-india DOI: 10.1177/0258042X19890245 journals.sagepub.com/home/mls Manish Das1 Debarshi Mukherjee1 Abstract In the era of globalization and technological advancements, ethnic identity (EID) is creating both opportunities as well as challenges for domestic and international marketers in formulating suitable marketing and branding strategies. This study attempts to investigate the role of EID in shaping consumers’ ethnocentric tendencies (CET). By analyzing data obtained from 385 surveys completed by Indian consumers, the study assessed the association of EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism. The findings showed that Association with Local Culture, Preserving Local Culture, Feelings towards Local Culture and Local Interpersonal Relationship enhance consumers’ CET. Materialism strengthens the effects of association for three EID dimensions and ethnocentrism, whereas acculturation weakens the association for three dimensions of EID. This study contributes to the literature, especially in the understanding of social identity theory. Practically, the findings are useful to marketers and retailers dealing with consumers in India in formulating their cultural branding strategies. Keywords Consumer ethnocentrism, ethnic identity, acculturation, materialism, social identity theory, hierarchical moderated regression Introduction Ethnocentrism analyzes the world from one’s own cultural perspective. It views one’s own culture superior over others. William Graham Sumner (1906) originated the term ethnocentrism in the field of 1 Department of Business Management, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar, Agartala, Tripura, India. Corresponding Author: Manish Das, Department of Business Management, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar, Agartala, Tripura 799022, India. E-mail: manishdas@tripurauniv.in 32 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) sociology. Sumner (1906) viewed ethnocentrism as the tendency to analyze the world from one’s in-group perspective and considering in-group superior to out-group. Shimp and Sharma (1987) popularized this term in management parlance as consumer ethnocentrism to represent the beliefs of consumers about the appropriateness and morality of purchasing foreign-made products. Ethnocentric consumers believe that their personal and national well-being would be under threat from imported products (Shimp & Sharma, 1987). Initial studies on consumer ethnocentrism considered this phenomenon applicable to advanced nations (Okechuku, 1994; Vida & Fairhurst, 1999); however, subsequent research (Klein, Ettenson, & Krishnan, 2006; Reardon, Miller, Vida, & Kim, 2005; Supphellen & Gronhaug, 2003) identified its applicability in advancing countries also (Renko, Karanovic, & Matic, 2012). Assessing ethnocentric tendency (CET) would give an idea about consumers’ inclination towards accepting or rejecting foreign/domestic made products and brands. The above discussion indicates that ethnocentric people will be more inclined towards their own country-made products and brands over imported one. Associated CET will serve either as an opportunity or as a threat for both domestic and imported products and brands to become successful in a particular market. One factor that may potentially influence the CET of a consumer is his/her associated ethnic identity (EID) as Rahman, Morshed, and Takdir (2011) observed that an ethnocentric person will assign highest importance to his/her own national and EID. When identity is articulated based on one’s own ethnic group affiliation, it is known as EID (Driedger, 1978). Ethnic identity can also be identified by one’s ethnic attitudes and values (White & Burke, 1987). EID reflects a persons’ belonging with his/her own ethnic group (Laroche, Kim, Hui, & Joy, 1996). In broad terms, EID is one’s identification based on personal or parental place of beginning (Pires & Stanton, 2000). Socialization process during childhood forms the basis for EID through learning of cultural values and behaviours (Rosenthal & Cichello, 1986). Since, socialization is a dynamic learning process, EID can vary over time (Pires, Stanton, & Cheek, 2003) and can be adjusted, altered as well as changed (Lindridge, 2010). The above discussion indicates that consumers’ EID has a significant bearing on their ethnocentrism tendency, which, in turn, will affect their intention to purchase domestic as well as imported items and brands. Since, successes for global as well as local brands require its acceptability among consumers, it is imperative to know the impact of consumers’ EID on CET. However, this relationship has not been studied in India. This indicates a gap in the literature. This gap will create challenges for both domestic and international marketers and retailers to market their products and brands among consumers in India. A lack of knowledge and understanding of consumers’ EID and its impact on CET hinders the marketers and retailers in developing an appropriate cultural branding and marketing strategies to effectively serve these consumers in India. A lack of knowledge in this regard will be a barrier to domestic and imported marketers and retailers in drawing this segment to purchase their products and brands through cultural branding. Hence, this study investigates the role of EID in shaping consumers’ CET. An integrated conceptual model is proposed for this purpose and it is empirically tested. Accordingly, this study first examines the influence of the dimensions of EID on CET among consumers in India. Second, this study examines the moderation effects of both acculturation (Acculturation to Global Consumer Culture, AGCC) and materialism (MAT) on the association between the dimensions of EID and CET among consumers in India. Acculturation and MAT have been considered as moderators due to the fact that, in the last couple of decades, increased globalization has resulted in the emergence of a ‘global culture’ (Carpenter, Moore, Alexander, & Doherty, 2012, 2013; Cleveland & Laroche, 2007; Lysonski, 2014; Lysonski & Durvasula, 2013) which is more or less synonymous with Western culture (Özsomer, 2012) due to Western dominance in global order (Raikhan, Moldakhmet, Ryskeldy, & Alua, 2014). Literature identified global consumers as those who are cosmopolitan in nature, speaks in English, more or less similar in their food habits, attire and life styles and try to measure success by materialistic pursuits Das and Mukherjee 33 (Cleveland, Laroche, & Takahashi, 2015; Lysonski, 2014; Özsomer, 2012). It means, for a believer of global culture, the tendency to deviate from own cultural identity (EID) and moving behind materials can probably be high. It indicates the possibility of acculturation and MAT as possible negative and positive moderators respectively, which will be elaborated in the literature review section in detail. This study has both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretical contribution of the study is to propose and empirically test a comprehensive model involving moderating role of acculturation and MAT in the EID impact on consumers’ CET in India. Apart from that, it will also significantly contribute to the existing literature of Social Identity Theory. This theory will be elaborated in the literature review section as well as in the research contribution section. Practically speaking, this study will inform both domestic and foreign marketers and retailers interested to market their items in India about the EID influence in shaping CET. This study will also give an idea about this impact in the light of acculturation and MAT as moderators in the association between EID and ethnocentrism. Findings from this study will support domestic and foreign marketers as well retailers immensely in formulating their cultural branding strategy while targeting consumers across India in particular as well as other closed Asian sub-continental nations due to the similarities with India in Hofstede’s dimension of national culture (Hofstede, 1984) in general. Literature Review Ethnic Identity Identity signifies one’s own characteristics and value systems (De Mooij, 2004). Thus, EID indicates one’s own characteristics and value systems based on the ethnic group with whom he/she associates by virtue of proximity by affiliation or origin. It is the natural identity with which a person was born and brought up (Pires & Stanton, 2010). EID is one’s assumed affiliation with a particular group, which can change, develop as well as renovate (Lindridge, 2010). EID is a behavioural guide that serves as a base while interacting with others (Burke & Stets, 2009). Extensive research has utilized EID as a measure for social and psychological change (Hirschman, 1981; Laroche, Kim, Tomiuk, & Bélisl, 2005). Researchers also tried to view consumption from EID perspectives contributing to consumer culture theory. For example, Dmitrovic, Vida, and Reardon (2009) opined that comparison of local and global consumption items (items belonging to different ethnic traditions) can be one important indicator for assessing strength of EID. Researchers also assumed national identity as a broader aspect of EID and tried to assess national identity from the consumption preference of multiple local and global items (Bardhi, Eckhardt, & Arnould, 2012; Cleveland et al., 2015). Consumer Ethnocentrism Shimp and Sharma (1987) coined the term consumer ethnocentrism (CE) to indicate the superiority feelings a consumer possess towards domestic products and brands vis-à-vis foreign alternatives. Thus, CET identifies the emotional and moral feelings of consumers’ in evaluating domestic products compared to foreign goods (Shimp & Sharma, 1987). Consumer ethnocentrism is a reflection of the view that consumption of foreign products is amoral, unpatriotic and has a negative impact on the domestic economy (Pentz, Terblanche, & Boshoff, 2015). Consumer CET is negatively correlated with purchase attitude of imported products and positively correlated with the purchase intension of domestic products 34 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) (Sharma, Shimp, & Shin, 1995). Ethnocentric consumers evaluate purchase of imported items and brands based on its impact on domestic economy (Shimp & Sharma, 1987). On the contrary, nonethnocentric consumers do not consider the origin of a product during purchase. They evaluate products and brands based on their own characteristics (Cutura, 2006). Ethnocentric consumers provide great emphasis and favour to the products that are produced in home country compared to the imported one (Jain & Jain, 2013) due to their superior view about domestic alternatives above the imported one (Auruskeviciene, Vianelli, & Reardon, 2012). Shimp and Sharma (1987) developed and validated an instrument known as ‘CETSCALE’ to measure people’s ethnocentric inclinations. Theoretical Linking Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) links the association of consumer ethnocentrism and EID. Social identity theory posits that people’s association with a particular social group makes them behave more favourably towards that group. This favourable impression regarding a particular group forms the basis and norms for individual behaviour. In order to increase self-image, people enhance the status of the group to whom they associate. Therefore, people divide the world into ‘them’ and ‘us’ through the process of social categorization. Social identity theory states that the ‘in-group’ will discriminate against the ‘out-group’ to enhance their self-image. Tajfel and Turner (1979) proposed that through the mental process of social categorization, social identification and social comparison, people evaluate others as either ‘us’ or ‘them’. This categorization also influences consumption decision of a person. Consumers are usually attracted to those products and brands that are linked to their social as well as national identity (Forehand, Deshpande, & Reed, 2002), that is, ‘us’. Alternatively, we can say that people will get attracted to those products and brands that represent their ‘in-group’. As EID also reflect national identity (Cleveland et al., 2015), it is expected that consumers with high EID will be usually attracted to national/domestic products and brands (in-group) compared to imported items (out-group). Since, CET measures consumers attitude towards domestic as well as imported items and brands, based on social identity theory, it can be conceived that people with high EID will have strong CET. EID Dimensions and Its Impact on Ethnocentric Tendency This section discusses about the dimensions of EID and its association with CET. Measurement of EID needs a multi-dimensional approach since one dimension cannot perfectly reflect people’s EID (Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001). Some of the significant dimensions of EID are self-attachment and identification with an ethnic group, urge to maintain own culture, ethnic involvement through customs, rituals, etc., extent of ethnic language use, ethnic media consumption, ethnic interpersonal relationship, etc. (Driedger, 1978; Hui, Annamma, Kim, & Laroche, 1992; Laroche et al., 2005; Mendoza, 1989; Peñaloza, 1994). Incorporating these dimensions, Cleveland and Laroche (2007) conceptualized and used one multi-dimensional instrument for measuring EID. Those dimensions were use of local media, association with local culture, preserving local culture, feelings towards local culture, local interpersonal relationship and use of local language. Present research used these dimensions as dimensions of EID. As discussed in theoretical linking, the association of EID and consumer ethnocentrism can be conceptualized with the underpinnings of ‘The social Identity Perspective’ that includes social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Social identity theory postulates that human beings are a combination of multiple identities: Das and Mukherjee 35 personal, social, and super ordinate (e.g., human). Social identity is central to group membership and ethnocentrism indicates a persons’ self-concept of membership towards a particular group (Tajfel, 1981). Two most important psychological variables according to Tajfel and Turner (1979) that affect ethnocentrism in a group are group categorization and the need for positive group distinctiveness. With identification of a particular group, people perceive themselves interchangeable with other members of the in-group and distant from members of out-group (Turner et al., 1987). Hence, group identity overtakes personal identity and people start discriminating and showing favourable behaviour towards their in-group to exhibit group superiority. Hence, once people categorize themselves as ethnic group members, they treat their ethnic group superior to other out-groups and starts putting favourable impression towards all components including diet, attire, customs, rituals, etc., of their ethnic group over other out-groups. Hence, CET in people increases. From the above discussion, it seems that EID enhances the CET that exist in an individual. Consequently, the dimensions of EID also seem to enhance the CET. The first dimension is use of local media (ULM). The exposure to the contents disseminated in the media influences people to learn culture (Alden, Steenkamp, & Batra, 1999; Appadurai, 1990). Thus, the more people are exposed to local media, the more likely they will have an inclination towards local culture. Types of television channel people frequently see, types of newspaper and magazines they frequently read, and types of songs and music they listen will have a significant bearing on their attitude and behaviour (Kim & Chao, 2009). As local media portrays favourable marketing communications for local items and brands (Kim & Chao, 2009), it is expected that interest towards local media will eventually create favourable impression towards local products and brands over foreign alternatives. It will strengthen their CET. Thus, we can articulate that, H1: Use of Local Media (ULM) will have a positive association with CET. The next dimension is association with local culture (ALC). People associate with local cultures through various socialization agents, which enable them to learn about that particular culture (Ger & Belk, 1996; Graddol, 2000). When people interact with and learn a new culture, they tend to use items widely accepted in that culture (Kim, 2015). Hence, the more a person will be associated with local culture and tradition, the more will be the tendency to exhibit favourable impression towards that culture (Laroche et al., 1996) and cultural items subsequently enhancing their CET. Thus, we argue that, H2: Association with Local Culture (ALC) will have positive association with CET. The next dimension is tendency to preserve local culture (PLC). The more people will be inclined to preserve local culture, the more will be their tendencies to identify with that cultural items and brands (Zhang & Shavitt, 2003). Thus, the more a person is inclined towards his/her local culture customs, habits, values and rituals, the more will be the tendency in him/her to preserve those habits, values and rituals (Vida, Dmitrović, & Obadia, 2008; White & Burke, 1987), which will gradually enhance the associated CET. Hence, we propose that, H3: Tendency to preserve local culture (PLC) will have a significant positive association with CET. The fourth dimension of EID is feeling towards local culture (FLC). People with high feelings of pride towards a particular culture will try to glorify that culture by claiming superiority of that culture over others (Vida et al., 2008). To glorify that culture, they may tend to associate more with the items of that culture while skipping other alternatives including foreign one (Vida et al., 2008). Hence, they will be 36 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) more ethnocentric in their consumption tendencies, indicating that FLC may have a positive association with ethnocentrism. Hence, we articulated that, H4: Positive feeling towards local culture (FLC) will influence CET positively. The next dimension of EID is local interpersonal relationship (LIR). People with strong interpersonal relationship tend to favour existing norms, traditions and belongings of that culture (Javalgi, Khare, Gross, & Scherer, 2005). It means, people with high local interpersonal relationship will cherish existing local culture norms, relations and social institutions (Javalgi et al., 2005), leading them to become more ethnocentric. Hence, we propose that, H5: High local interpersonal relationship (LIR) will influence CET positively. The final dimension of EID is use of local language (ULL). People tend to exhibit a superior image for that culture whose language they use during communication (Wiseman, Hammer, & Nishida, 1989). This is because language indicates bonding with a particular culture. Hence, the more people will use local language during communication, the more they will be bonded with local culture leading to increased CET. Thus, we can hypothesize that, H6: Use of local language (ULL) will have a significant positive association with CET. Moderating Role of MAT MAT can moderate the association between dimensions of EID and consumer CET. MAT indicates a person’s inclination towards material possessions is defining major life goals (Alden et al., 1999; Richins, 2004). Materialists tend to demonstrate their success and social statuses to others through acquisition of status and conspicuous items (Richins & Dawson, 1992; Vigneron & Johnson, 2004). MAT is associated with both consumer ethnocentrism as well as EID. Cleveland, Laroche, and Papadopoulos (2009), Cleveland et al. (2011), Cleveland, Laroche, and Hallab (2013) conducted multiple research across the world involving both Western and Asian countries concerning MAT’s association with EID. None of the studies observed any significant negative association between EID and MAT. However, studies by Cleveland et al. (2011, 2013) showed significant positive association of EID dimensions and MAT concluding that MAT is an ethnically compatible phenomenon. Majority dimensions of EID exhibited either significant positive association with MAT or no association. Again, MAT can have association with consumer ethnocentrism also. Though, consumer ethnocentrism is one of the significantly researched area in the parlance of consumer behaviour research; interestingly, there is a scarce in literature that investigated MAT as an antecedent of consumer CET (Tantray, 2018). However, a four-country study by Clarke et al. (2000) observed a significant positive association of MAT and ethnocentrism. The above discussion indicates that MAT may have a significant positive association with EID as well as consumer ethnocentrism. Hence, the following hypotheses are formulated in relation to moderation impact of MAT in the association of EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism: H7: MAT positively moderates (enhances) the association between the customers’ (a) use of local media; (b) association with local culture; (c) preserving local culture; (d) social feelings towards local culture; (e) local interpersonal relationship and (f) use of local language; and their CET. Das and Mukherjee 37 Moderating Role of Acculturation Acculturation tendencies of a consumer can also influence the association of EID dimensions and ethnocentrism. Acculturation studies socio-cultural change (Trimble, 2003) and researchers (Craig, Douglas, & Bennet, 2009; Lysonski, Durvasula, & Madhavi, 2012; Yaprak, 2008) are convinced that local cultures in the developing countries are exhibiting rapid changes. Globalization drives acculturation (Cleveland & Laroche, 2007; Cleveland et al., 2009; Craig & Douglas, 2006) and in the process reflects cultural changes through the adoption of products, lifestyles and rituals (Craig & Douglas, 2006) mainly of the developed nations (Ger & Belk, 1996). Acculturation can be viewed from two perspectives: unidirectional and bi-directional. Unidirectional view considers acculturation as shifting of one culture to another while decaying the first. Bi-directional view calls for maintaining own culture and acquiring the alternative cultural traits and values either by assimilation or integration (Cleveland et al., 2015; Strizhakova, Coulter, & Price, 2012). Consumer acculturation is one sub-set of acculturation, where acculturation is reflected through consumption of products and brands by the consumers. Consumer acculturation is the phenomenon of changing consumption culture where consumers start consuming items that are symbols of other cultures (Cleveland et al., 2009). For measuring consumer acculturation, Cleveland and Laroche (2007) conceptualized one multi-item multi-dimensional instrument popularly known as AGCC scale. The dimensions identified by Cleveland and Laroche (2007) are Cosmopolitanism, Exposure to global media, Exposure to marketing activities of MNC’s, Self-identification with global consumer culture, Contact with foreigners through travel, and Openness to global consumer culture. According to Cleveland and Laroche (2007), a high tendency towards all these dimensions will ensure an overall acculturation tendency of a person towards global consumer culture. Strength of acculturation tendency plays a significant role in shaping consumer’s EID (Cleveland & Laroche, 2007). Though, not a single study investigated this phenomenon in Indian context, but there are many studies that viewed the association of consumer acculturation and EID from multiple country perspective as well as from migrated consumers’ perspectives. Majority of the findings reported a significant negative association of consumer acculturation and EID (Cleveland & Laroche, 2007; Cleveland et al., 2009, 2013; Li, Marbley, Bradley, & Lan, 2016; Sobol, Cleveland, & Laroche, 2018). Again, consumer acculturation can have association with CET also. Since ethnocentric people prefer local made products and brands over global one, and consumer acculturation studies the tendency of consumers culture change towards global culture through acquisition of items and brands, a negative association among consumer acculturation and CET is expected. In fact, studies (Cleveland et al., 2009; Sobol et al., 2018) also recorded a significant negative association between consumers CET and acculturation tendencies. The above discussion indicates that consumer acculturation will play a significant role as a moderator in the association between EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism. Most expectedly, consumer acculturation will weaken the strength of association among EID dimensions and CET. Hence, the following hypotheses are drawn in relation to the moderating role of consumer acculturation in the association of EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism. H8: Consumer acculturation negatively moderates (weakens) the association between customers’ (a) use of local media; (b) association with local culture; (c) preserving local culture; (d) social feelings towards local culture; (e) local interpersonal relationship and (f) use of local language; and their CET. 38 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) The Proposed Conceptual Model Based on the review of literature and the preceding hypotheses, a conceptual model is proposed for empirical validation given in Figure 1. Research Method Sample and Survey Administration Responses were collected from consumers in India. Presently India is world’s sixth largest economy with an estimated size of $2.6 trillion (IMF, 2018). The economy had grown at a rate of above 7 per cent for the last three consecutive years and expected to grow at 8 per cent and above in coming years (IMF, 2018). The above statistics suggest that assessing the EID impacts on consumer ethnocentrism will have significant bearing for marketers and retailers dealing with culturally sensitive items and brands in India. Furthermore, their acculturation and materialistic tendencies will be likely to influence the association of EID dimensions and CET, which will subsequently influence the consumption habits of Indian consumers. Hence, Indian consumers are considered as appropriate sample for this study. Survey method was employed for data collection purpose and a structured questionnaire is used for survey purpose. Data were collected through both online and offline modes. The online questionnaire Figure 1. Conceptual Model for This Study Source: The authors. 39 Das and Mukherjee was administered via email. Apart from that, respondents were also approached through other networking sites, such as Facebook, LinkedIn and WhatsApp. A total of 262 usable surveys were received and used for analysis. A reminder email was sent 10 days after the first mail. Offline data were collected by visiting shopping malls, standalone retail outlets and educational institutes. Formal permission to administer the survey was sought form respective authorized person of the institution. Both on the spot response and own convenience based reply options were given to the survey respondents. To respondents who opted to respond at a later point of time, postage paid selfaddressed envelopes were provided. 123 usable responses were received and used for analysis through offline survey. A total of 385 fully usable responses were obtained through offline and online mechanisms of data collection. Data were collected during January 2018–April 2018. Independent sample T-test was employed to observe whether any significant difference exists among the early and late respondents in relation to their demographic attributes. No significant difference in responses indicated a non-response bias (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). To observe representativeness, accuracy and non-response bias between online and offline survey respondents, independent sample T-test was further used. No significant difference among online and offline respondents in relation to demographic profiles or study constructs justified validity of both the mechanisms for data collection (Deutskens, Ruyter, & Wetzels, 2006). Demographic profiles of the samples are given in Table 1. Measures and Instrument Development Previously validated instruments were used for survey purpose. However, certain modifications in the wordings are made to suit the context of the study. The instrument comprised three parts: Part A contains the screening question; Part B measured the study constructs; and Part C collected demographic information of the respondents presented in Table 1. EID was measured by items and dimensions adopted from Cleveland and Laroche (2007). Specifically, use of local media was operationalized using three items, association with local culture using six items, preserving local culture by using three items, social feelings towards local culture by using three items, local interpersonal relationship by using three items Table 1. Demographic Profiles of the Respondents (n = 385) Category Gender Male Female Income (1$ = 70 Indian Rupees) Less than USD200/month USD 201–400/month USD 401–600/month Above USD 600/month Educational Qualification Higher Secondary Bachelor’s Degree Postgraduate Degree or higher Source: The authors. N(385) % 209 176 54 46 95 113 87 90 24.7 29.3 22.6 23.4 133 180 72 34.6 46.7 18.7 40 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) and use of local language was operationalized by using six items. For measuring consumers’ materialistic tendencies, a four items version of Richin’s (2004) ‘materialism scale’ was used. Consumer ethnocentrism was operationalized using a five-item version of CETSCALE (Shimp & Sharma, 1987). Consumer acculturation was measured using AGCC scale by Cleveland and Laroche (2007). Acculturation tendency was measured through four dimensions obtained from AGCC scale namely Cosmopolitanism, English language usage, Global mass media exposure and Exposure to marketing activities of MNC’s. Cosmopolitanism was conceptualized by using five items, English language usage by six items, Global mass media exposure by five items and Exposure to marketing activities of MNC’s was operationalized by using four items. All the responses were obtained in a 7-point Likert measurement format (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Past literature identified the role of demographic variables like education, employment status and gender in determining consumer CET (Javalgi et al., 2005; Sharma et al., 1995); hence, these variables were controlled during analyses. A group of marketing and consumer behaviour professors content tested the instrument for ensuring face validity. Analysis and Results Measurement Model Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS version 21 to determine the validity, reliability and dimensionality of the constructs. In obtaining the final set of items for each construct, one item was deleted from cosmopolitanism dimension, two from use of local media dimension, and one each from preserving local culture and feeling about local culture dimensions based on item-to-total correlations and the standardized residual values (Byrne, 2010). The items were examined with original conceptual definition of the constructs. The remaining items were subjected to CFA. The standardized solution using AMOS 21 through the maximum likelihood method indicated an acceptable factor loading for the remaining items in their respective factors. This indicates the instruments’ unidimensionality and validity. Table 2 indicates the values of the CFA measurement model. Average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) values were above 0.5 and 0.7 respectively, indicating convergent validity of the variables (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). A factor loading of 0.7 and above for all the constructs (p < 0.01) also ensured the additional indication of convergent validity for the constructs (Hair et al., 2010). Discriminant validity was measured by using procedures proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981). The results given in Table 3 show that the diagonally presented square root of the AVE values of each construct were higher than the correlation coefficient of the corresponding construct, indicating the discriminant validity of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 2 indicates the fit statistics of the CFA model as CMIN/DF = 3.85 ( p < 0.001), CFI = 0.91, GFI = 0.88, AGFI = 0.87, NFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.061. All the fit statistics are within the prescribed limit as identified by Hair et al. (2010). Table 3 indicates the mean, standard deviation and correlation coefficients among the measurement dimensions. As evident from Table 3, the square root of AVE (presented in diagonal) is greater than the dimensional correlation coefficients indicating the discriminant validity of the instrument. All the correlation values were less than 0.9, confirming the absence of multicollinearity (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2012). 41 Das and Mukherjee Table 2. Construct for Measurement with Validity and Reliability Acculturation I am interested in learning more about people who live in other countries I like to learn about other ways of life I like to try restaurants that offer food that is different from that in my own culture I enjoy exchanging ideas with people from other cultures or countries I find people from other culture stimulating English Language Usage (ELU) I feel very comfortable speaking in English I often speak English with my family and friends AVE (0.69), CR (0.88), I speak English regularly α = 0.88 The songs I listen are almost all in English Most of the textbooks and articles I read are in English Many of my favourite shows of TV are in English Global Mass Media Exposure (GMM) I enjoy watching Hollywood films at the theatre Some of my favourite actors/actresses are from Hollywood AVE (0.74), CR (0.95), I am listening to music that is popular in the United States α = 0.91 I enjoy watching Hollywood movies that are in English In general, I do not like American Television(r) Ads for foreign of global products are everywhere Exposure to Marketing of MNC’s When I read a newspaper, I come across many advertisements (EXM) for foreign or global products AVE (0.67), CR (0.82), When I am watching Television, the number of advertisements α =0.84 for foreign brands is quite high than local brands I often watch TV programming with advertisements from outside my country Ethnic Identity Use of Local Media (LM) Most of the TV channels I observe are local channels AVE (0.63), CR (0.72), Most of the newspaper and magazine I study are local α = 0.75 I prefer local videos/movies over Hollywood one Association with Local Culture (AC) I always celebrate (local culture) holidays AVE (0.77), CR (0.91), I like to celebrate birthdays and weddings in the (local culture) α = 0.87 tradition I like to cook (local culture) dishes/meals I like to eat (local culture) foods I like to listen (local culture) music Participating in (local culture) events is very important to me Preserving Local Culture (PC) I consider it very important to maintain my own culture I believe that it is very important for children to learn the values AVE (0.66), CR (0.79), of own culture α =0.79 I was to live elsewhere; I would still want to retain my own culture Cosmopolitanism (COS) AVE (0.61), CR (0.82), α = 0.81 0.72 0.76 0.81 0.75 0.77 0.82 0.75 0.87 0.88 0.79 0.86 0.81 0.91 0.80 0.88 0.76 0.76 0.82 0.67 0.81 0.70 0.71 0.73 0.84 0.83 0.70 0.78 0.86 0.82 0.76 0.62 0.71 (Table 2 continued) 42 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) (Table 2 continued) Feelings towards Local Culture (FLC) I feel very proud to identify with my own culture AVE (0.69), CR (0.87), I consider my culture rich and precious than all other cultures α =0.86 My local culture people has the most positive impact on my life Local Interpersonal Relationship (LIR) Most of my friends are members of my own cultural group AVE (0.73), CR (0.85), Most of the people that I go to parties or social events with are α =0.84 members of my own culture group Most of the people at the places I go to have fun and relax are members of my own culture group Use of Local Language (L) I speak my own local language regularly AVE (0.67), CR (0.82), The songs I listen to are almost all in local language α =0.81 Many of my favourite television shoes are in local language I always speak/spoke local language with my parents Many of the books I read in are in local language I prefer to watch local language television over any other language I may speak Consumer Ethnocentrism Indian should not buy foreign products, because this hurts Indian businesses and causes unemployment Consumer Ethnocentrism (CET) AVE (0.71), CR (0.84), It may cost me in the long run, but I prefer to support Indian α = 0.84 products Foreign products should be taxed heavily to reduce their entry into India Indian consumers who purchase products made in other countries are responsible for putting their fellow Indians out of work Purchasing foreign made products is Un-Indian Materialism (MAT) AVE (0.71), CR (0.73), α = 0.82 Materialism I admire people who own expensive homes, cars and cloths I like to own things that impress The things I own say a lot about how well I am doing in life I try to keep things simple, as far as possessions are concerned (r) 0.80 0.76 0.83 0.79 0.82 0.83 0.76 0.73 0.79 0.81 0.78 0.75 0.77 0.78 0.81 0.79 0.78 0.72 0.76 0.78 0.79 Source: The authors. Notes: CMIN/DF = 3.85 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.91, GFI = 0.88, AGFI = 0.87, NFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.061 FL = Factor Loading, α = Cronbach’s Alpha, CR = Construct Reliability, AVE = Average variance extracted, DF = Degrees of Freedom, CFI = Comparative Fit Index, GFI = Goodness Fit Index, AGFI = Adjusted Goodness Fit Index, NFI = Normed Fit Index, TLI = Trucker-Lewis Index, RMSEA = Root Mean square Error of Approximation, r = reverse coded. 3.61 2.39 2.88 4.27 3.01 4.02 4.76 4.24 4.12 3.11 4.93 3.23 0.79 1.23 1.02 0.99 0.83 1.42 0.79 1.06 0.71 1.21 0.72 1.1 SD 2 0.83a 0.57** 0.43** −0.25* −0.41** −0.33** −0.17* −0.38** 0.21* −0.07ns 0.12ns 0.78 0.31** 0.53** 0.27* −0.18* −0.33** −0.09ns −0.32** −0.19* −0.09ns −0.21* 0.26* a 1 0.86a 0.51** −0.29* −0.26* −0.32** −0.21* −0.21* −0.18* −0.22* 0.57** 3 0.82a 0.02ns −0.35** −0.11ns −0.10ns −0.37** −0.19* −0.08ns 0.49** 4 0.79a 0.51** 0.39** 0.23* 0.23* 0.17* 0.12ns 0.34** 5 Source: The authors. Notes: ** Correlation is significant at p < 0.01, * Correlation is significant at p < 0.05, nsNot Significant a Diagonal value indicates the square root of AVE of individual latent construct 1. Cosmopolitanism 2. English Language Usage 3. Global Mass Media Exposure 4. Exposure to Marketing of MNC’s 5. Use of Local Media 6. Association with Local Culture 7. Preserving Local Culture 8. Feelings towards Local Culture 9. Local Interpersonal Relationship 10. Use of Local Language 11. Consumer Ethnocentrism 12. Materialism Mean Table 3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix for the Study Constructs 0.88a 0.65** 0.38** 0.31** 0.34** 0.56** 0.44** 6 0.81a 0.52** 0.56** 0.23* 0.42** 0.09ns 7 0.83a 0.35** 0.55** 0.36** 0.21* 8 10 11 0.85a 0.28* 0.82a 0.41** 0.12ns 0.84a 0.31** 0.11ns 0.23* 9 0.84a 12 44 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) Common Method Bias One vital consideration during survey research is occurrence of common method bias (CMB). Marker variable method as suggested by Malhotra, Kim, and Patil (2006) is used to test CMB. Accordingly, one variable is added as a marker in the study, which is conceptually unrelated to the study constructs. The low correlation between the marker and the study constructs was indicated the non-occurrence of CMB (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). Hypotheses Testing Hierarchical moderated regression method was employed to test the hypotheses formulated in this study. The predictor variables were considered as input to generate interaction terms (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991). Across the three regression analysis models, the highest VIF value was 3.96. It was much lesser than the prescribed limit of 5 (Hair et al., 2010). This indicates the absence of multicollinearity in the models. In all the three models, consumer CET was the outcome or dependent variable. The impact of the control variables was evaluated in Model 1. The direct association of the six dimensions of EID with consumer CET was evaluated in Model 2. Both the moderator variables, that is, consumer acculturation and MAT were also included in Model 2 to observe the direct effects of the moderators in the outcome variable. The R2 difference between Model 1 and Model 2 was observed to be significant. It indicates the direct effects on consumer ethnocentrism by the dimensions of EID. In Model 3, the moderator variables were introduced. The interaction terms of moderator variable and independent variables were put as separate independent variables while running the model. A significant change in R2 value between Model 2 and Model 3 will indicate significant moderation effects. As evident in Table 4, the results of Model 1 (i.e., all the control variables included in the study) explained 11 per cent variance in CET and Model 2 (i.e., the six dimensions of EID, consumer acculturation, and MAT along with the control variables) explained 43 per cent variance in consumer ethnocentrism, with a F-value of 3.52 (p < 0.001). A significant difference in R2 between Model 1 and Model 2 (ΔR2= 0.32, F = 3.52, p < 0.001) suggests the presence of direct effects of EID dimensions on consumers’ CET. Model 2 showed that Association with Local Culture (β = 0.26, p < 0.01), Preserving Local Culture (β = 0.24, p < 0.01), Feelings towards Local Culture (β = 0.16, p < 0.05), and Local Interpersonal Relationship (β = 0.34, p < 0.001) had significant positive influences on consumer CET, whereas Customer Acculturation had a significant negative influence (β =−0.25, p < 0.01) on ethnocentrism. Use of Local Media (β = 0.014, p > 0.05), Use of Local Language (β = 0.01, p > 0.05) or MAT (β = 0.06, p > 0.05) had no significant effects on CET. Thus, H2, H3, H4 and H5 were accepted where as H1 and H6 were not accepted concerning the direct effects on consumer CET. Model 3 assessed the moderation effects of acculturation and MAT in the direct association of EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism. The model explained 66 per cent variance in consumer CET. A significant R2 difference between Model 2 and Model 3 (ΔR2= 0.23, F = 9.18, p < 0.001) suggested the presence of interaction effects of consumer acculturation and MAT. The test of individual interaction effects of MAT suggests that the interaction terms of Use of Local Media and MAT (β = 0.14, p < 0.05); Association with Local Culture and MAT (β = 0.19, p < 0.05); and Local Interpersonal Relationship and MAT (β = 0.23, p < 0.01) were positive and significant. Thus, MAT positively moderates the association of three EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism, indicating acceptance of H7a, H7b and H7e. The interaction terms of Preserving Local Culture and MAT (β = 0.08, p > 0.05); Feelings towards Local Culture and MAT (β = 0.04, p > 0.05); and Use of Local Language and MAT (β = 0.01, p > 0.05) were not significant. Thus, H7c, or H7d or H7f were not supported. 45 Das and Mukherjee Table 4. Results of Hierarchical Moderated Regression Analyses Dependent Variable: Consumer Ethnocentrism Independent Variables Control Variables Gender Education Employment Direct Effect Variables Use of Local Media Association with Local Culture Preserving Local Culture Feelings towards Local Culture Local Interpersonal Relationship Use of Local Language Acculturation Materialism Interactions Use of Local Media X Acculturation Association with Local Culture X Acculturation Preserving Local Culture X Acculturation Feelings towards Local Culture X Acculturation Local Interpersonal Relationship X Acculturation Use of Local Language X Acculturation Use of Local Media X Materialism Association with Local Culture X Materialism Preserving Local Culture X Materialism Feelings towards Local Culture X Materialism Local Interpersonal Relationship X Materialism Use of Local Language X Materialism R2 value Δ R2 F value F significance *** p < 0.001 ** p < 0.01 * p < 0.05 ns not significant Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 0.14* 0.01ns 0.12* 0.19* 0.02ns 0.08ns 0.17* 0.05ns 0.07ns 0.014ns 0.26** 0.24*** 0.16* 0.34*** 0.01ns −0.25** 0.06ns 0.02ns 0.28** 0.37*** 0.18* 0.37*** 0.07ns −0.32** 0.03ns 0.43 0.32 4.52 (p < 0.001) −0.02ns −0.24** −0.16* −0.32*** −0.04ns 0.02ns 0.14* 0.19* 0.08ns 0.04ns 0.23** 0.01ns 0.66 0.23 8.18 (p < 0.001) 0.11 – 0.597 (p > 0.05) Source: The authors. Individual interaction effects of consumer acculturation indicated that the interaction terms of Association with Local Culture and Acculturation (β = −0.24, p < 0.01); Preserving Local Culture and Acculturation (β = −0.16, p < 0.05); and Feelings towards Local Culture and Acculturation (β = −0.32, p < 0.001) were negative and significant. Thus, consumer acculturation negatively moderates the association of three EID dimensions and CET, accepting H8b, H8c and H8d. The interaction terms of Use of Local Media and Acculturation (β = −0.016, p > 0.05); Local Interpersonal Relationship and Acculturation (β = −0.04, p > 0.05); and Use of Local Language and Acculturation (β = 0.02, p > 0.05) were not significant. Thus, H8a, or H8e or H8f were not supported. 46 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) Auto-correlation is another significant aspect in hierarchical moderated regression to ensure robustness of a model. To ensure the phenomenon of auto correlation, the Durbin–Watson test was employed during analysis. The analysis resulted a test value of 1.972, which is within the prescribed limit (Thomas, Fomby, Carter, & Johnson, 1984) ensuring its absence. Predictive Validity Predictive validity measure of the model was also ensured by applying cross-validation procedure (Woodside & MacDonald, 2012). Accordingly, all the 385 samples were randomly grouped into two categories of 192 and 193 samples and Model 3 of hierarchical moderated regression was run for both the sub-samples. The associations of the variables in the sub-samples showed the same pattern of positive or negative significance. The R2 values of consumer CET for both subsamples were very close to each other (between 64.9% and 69.5%), indicating the predictive validity of the model. Discussion This study proposed one comprehensive moderation model to understand how consumers’ EID is associated with ethnocentrism tendency. Three sets of hypotheses are specifically designed and tested in this regard. The first set of hypotheses examined the direct association of EID dimensions and CET. The findings indicate that four dimensions of EID (Association with Local Culture, Preserving Local Culture, Feelings towards Local Culture, and Local Interpersonal Relationship) had significant positive association with CET of the consumers in India. However, Use of Local Media and Use of Local Language dimensions do not have any significant association with ethnocentrism. The findings of the four positive significant dimensions are consistent with the past findings given in the literature review section (Banna, Papadopoulos, Murphy, Rod, & Mojas-Mendex, 2018; Javalgi et al., 2005; Zarkada-Fraser & Fraser, 2002). However, Use of Local Media and Use of Local Language dimensions had not any significant association with CET for consumers in India. The justification for Use of Local Media impact on ethnocentrism can be attributed to the fact that communication carried out by local media in India in present time are more or less homogeneous with global media houses. Though aired in local language, the content deliberation pattern and style, content structure is similar to their global counterparts. Even, multinationals also frequently air their global advertisements with minor changes to target consumers through local media houses. Hence, use of local media as a determinant failed to enhance CET of the consumers in India. Insignificant association of local language usage and ethnocentrism impact can be attributed to the fact that along with local language, consumers in India are equally compatible and familiar with English as a second language. Even, Indian consumers frequently use ‘Hinglisha portmanteau of Hindi and English’ in their day-to-day conversations with others. Hence, usage of local languages failed to enhance CET for the consumers in India. The second set of hypotheses in this study dealt with the moderating effect of MAT in the association between EID dimensions and ethnocentrism among consumers in India. The findings show that MAT acts as a positive moderator for the association between three dimensions of EID (Association with Local Culture, Local Interpersonal Relationship and Local Media usage) and ethnocentrism. These findings are in line with the expected outcome discussed in literature review section. However, MAT failed to explain the moderation hypotheses for Preserving Local Culture, Feelings towards Local Culture, and Use of Local Language dimensions. Materialists tend to demonstrate their success and Das and Mukherjee 47 social statuses to others through acquisition of status and conspicuous items (Richins & Dawson, 1992; Vigneron & Johnson, 2004). Since, the purpose of materialistic tendencies is to exhibit success and status to others; it has no bearing on any of these dimensions, that is, preserving local culture, positive feeling towards local culture and use of local language. Another possible reason could be that, in India, MAT prevailed since ancient in different forms across cultures (Bhattacharya, 2016). Materialistic instinct among Indian’s is not culture or ethnicity specific rather it is more independent and self-governed by nature without consideration for right and wrong (Bhattacharya, 2016). Hence, it is quite possible that there is no association of these EID dimensions with MAT in the context of India. The third set of hypotheses relates to the moderation effects of consumer acculturation. Acculturation acts as a negative moderator for the association between three EID dimensions (Association with Local Culture, Preserving Local Culture, and Feelings towards Local Culture) and CET. These findings indicate that as people become acculturate, the positive effects of these dimensions on the CET weakened. These findings are consistent with the discussions in the literature review section. However, consumer acculturation does not have any significant moderation effect on the impact of the remaining three dimensions of EID (i.e., Use of Local Media, Local Interpersonal Relationship, and Use of Local Language) on the CET. Since, Use of Local Media and Use of Local language dimensions do not have any significant direct impact on CET of consumers; consumer acculturation plays an insignificant role in these effects. Though Local Interpersonal Relationship is observed to have a significant direct positive effect with consumer ethnocentrism, the moderation effect of consumer acculturation in this direct effect becomes insignificant. This may be attributed to the fact that India being a collectivist country, local interpersonal relationship is prominent and vital irrespective of associated level of acculturation. Hence, consumer acculturation does not play any significant role as a moderator for this dimensions impact on CET. Academic Implications This study has investigated how dimensions of EID influence consumers’ CET in India. It also analyzed the moderating role of MAT and acculturation in the direct association of dimensions of EID and consumer ethnocentrism. A conceptual model was proposed in this regard and the findings obtained from this study more or less supported the proposed model though the findings relating to some hypotheses were not significant. EID, acculturation, consumer ethnocentrism and MAT are some of the important cultural constructs affecting consumer behaviour significantly post globalization era. However, their interrelationship has not yet been investigated extensively in India. By proposing one conceptual model and empirically testing it, this study fills this gap. This study also contributes in better understanding of Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Social identity theory claims that people association with a particular social group indulge them to behave more favourably towards that group and gradually this favourable impression regarding the group becomes the norms for individual behaviour. As EID is a form of social identity, we can say, people association towards a particular ethnic group tends them to act favourably towards that ethnic group. Explaining the association further, it can be told that people with particular national identity will act favourably towards that nation as well as nation made products. Hence, social identity theory tells that EID will have a significant positive association with consumer ethnocentrism. The findings of this study validate this phenomenon to a greater extent as it shows that, out of six dimensions of EID, four dimensions have positive association with ethnocentrism for consumers in India. Hence, it is a significant contribution in the existing knowledge base of social identity theory with a new application area of consumption and culture. 48 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) Apart from EID association with consumer ethnocentrism, our study also assessed the moderating role of acculturation and MAT in the association between EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism. Our study identified acculturation as a negative moderator and MAT as a positive moderator in the direct association of EID dimensions and consumer ethnocentrism. By doing so, our study further expanded the current literature base of social identity theory in the light of moderation role of MAT and acculturation. It is also noteworthy that this study was conducted in India. India is the second most populated country after China, with huge young and middle-aged population having a high disposable income (Saxena, 2010). The Indian economy has exhibited an impressive GDP growth during the last decade. With its high disposable income, Indian consumers are an attractive market for multinational as well as domestic firms. However, due to accelerated globalization and technological revolution, customers in India are witnessing cultural transitions and modernization (Ghosh, 2012) creating behavioural uncertainties while taking purchase decision. These cultural paradoxes are creating both opportunities as well as challenges for marketers in formulating and executing their cultural branding strategies; thus contributing towards cultural branding domain of consumer behaviour confining to Indian consumer. Managerial Implications This study provides several managerial contributions for marketers and retailers who primarily rely on cultural branding while market their offerings to consumers in India. These implications are briefly elaborated as follows: Of the dimensions of EID, consumers’ association with local culture has significant positive influence on their CET indicating that with increased association with local culture, consumers’ CET increases. Thus, marketers interested to target consumers based on their ethnocentric feeling, can encourage them to associate with local culture. In addition, they can encourage consumers to enhance local interpersonal relationship and preservation of local culture. For example, marketers can arrange promotional offers based on contests encouraging local association. They can also organize events to popularize local cultural songs and singers and in the process can contribute in preserving local cultural traditions. These promotional activities among target customers will enhance ethnocentric feelings and fetch additional benefits for marketers through cultural branding. Again, findings from this study also indicate a significant positive association of feeling towards local culture and CET. It means, while targeting consumers in India, marketers as well as retailers can glorify local cultural feelings and sentiments through advertisement and public relation activities. For example, they can highlight the unique aspects of local cultures in their advertisement through emotional advertisement appeal. They can also take steps towards preserving the local cultural heritage, customs and traditions. Service-oriented organizations can incorporate cultural traditions as an integral part of their service delivery process. These initiatives and activities will enhance consumers’ ethnocentric image and will benefit the marketers tremendously. Our findings also indicated that MAT act as a positive moderator for the direct association of three dimensions of EID (Association with Local Culture, Local Interpersonal Relationship and Local Media usage) and CET. These findings suggest that promoting materialistic appeals and thoughts while focussing on these three dimensions of EID will arouse more ethnocentric feeling among consumers. It is therefore recommended that while glorifying these three dimensions (as discussed in the previous section) through marketing communications, marketers can promote materialistic values. It will further enhance the ethnocentric feeling of the target consumers. Das and Mukherjee 49 The findings also indicated that the consumers’ acculturation tendency weakens the association of three dimensions of EID (Association with Local Culture, Preserving Local Culture, and Feelings towards Local Culture) and CET. These findings are vital for marketers and retailers who mainly market imported and foreign items and brands in India. These marketers and retailers may use acculturation appeals while focussing these dimensions to reduce consumers’ CET. For example, they can use slogans like ‘Global by Look Local by Heart’ to manifest their global nature along with love for local culture. They can also promote and organize events (e.g., ‘Fusion’ theme based music and fashion shows) to promote global culture and at the same time showing bond with local culture. Overall, these findings will support practising marketers and managers in effective design and execution of their communication and branding strategies while targeting Indian market. Limitations and Directions for Future Research This study has certain limitations that future researchers may resolve. First, this study is confined to consumers in India. In India also, offline data were mainly collected from East and Northeastern parts. Due to huge population and socio-cultural differences within India as well as with other countries, generalizing these findings is questionable. So, the proposed model should be replicated in other parts of India as well as other counties across the world for better generalization. The second inherent limitation for this study is its cross-sectional nature, which can only detect association between variables but cannot detect cause-and-effect relationships between the variables (Hair Jr., Lukas, Miller, Bush, & Ortinau, 2014). From the study perspective, it means that EID dimensions cause variations in CET for consumers in India. Future researchers can carry out longitudinal studies to observe these associations. This study opens multiple dimensions for future research. First, the model proposed in this study is a generalist one and not confined to any particular product or product categories. Future researchers can use this model to investigate how the EID dimensions drive consumers’ intentions to purchase different types of products and brands in the light of CET; for example, imported Western food, imported technology products, fashion items, etc. Second, the proposed model can further expanded by including other moderators as well as new mediators in the moderated associations. Future researchers could identify these factors from the literature, incorporate them into the model, and expand the study. Third, similar studies could be conducted between different groups of consumers based on their demographic profiles (e.g., between married and single customers, and between customers with different educational or occupational backgrounds) to see whether based on demographic attributes is there any significant difference in the model. Such studies may provide insights to the marketers and retailers who intend to apply cultural branding while market brands and items to the consumers in India. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. ORCID iD Manish Das https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0579-2807 50 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) References Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. New York, NY: SAGE Publications. Alden, D. L., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Batra, R. (1999). Brand positioning through advertising in Asia, North America, and Europe: The role of global consumer culture. Journal of Marketing, 63(1), 75–87. Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Theory, Culture & Society, 7(2/3), 295–310. Armstrong, S. J., & Overton, S. T. (1977). Estimating nonresponsive bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396–402. Auruskeviciene, V., Vianelli, D., & Reardon, J. (2012). Comparison of consumer ethnocentrism behavioural patterns in transitional economies. Transformations in Business and Economics, 11(2/26), 20–35. Banna, E. A., Papadopoulos, N., Murphy, A. S., Rod, M., & Mojas-Mendex, I. J. (2018). Ethnic identity, consumer ethnocentrism, and purchase intensions among bi-cultural ethnic consumers: ‘Divided loyalties’ or ‘dual allegiance’? Journal of Business Research, 82, 310–319. Bardhi, F., Eckhardt, M. G., & Arnould, E. (2012). Liquid relationship to possessions. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(3), 510–529. Bhattacharya, R. (2016). From proto-materialism to materialism: The Indian scenario. confluence. Journal of World Philosophies, 3. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.iu.edu/iupjournals/index.php/confluence/article/view/544 Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Multivariate Applications Series. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. Carpenter, J. M., Moore, M., Alexander, N., & Doherty, M. A. (2012). Acculturation to the global consumer culture: A generational cohort comparison. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 20, 411–423. Carpenter, J. M., Moore, M., Alexander, N., & Doherty, A. M. (2013). Consumer demographics, ethnocentrism, cultural values, and acculturation to the global consumer culture: A retail perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 29, 271–291. Cleveland, M., & Laroche, M. (2007). Acculturation to the global consumer culture: Scale development and research paradigm. Journal of Business Research, 60(3), 249–259. Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Hallab, R. (2013). Globalization, culture, religion, and values: Comparing consumption patterns of Lebanese Muslims and Christians. Journal of Business Research, 66, 958–967. Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Papadopoulos, N. (2009). Cosmopolitanism, consumer ethnocentrism and materialism: An eight country study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of International Marketing, 17(1), 116–146. Cleveland, M., Papadopoulos, N., & Laroche, M. (2011). Identity, demographics, and consumer behaviors: International market segmentation across product categories. International Marketing Review, 28(3), 244–266. Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Takahashi, I. (2015). The intersection of global consumer culture and national identity and the effect on Japanese consumer behavior. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 27(5), 364–387. Cleveland, M., Papadopoulos, N., & Laroche, M. (2011). Identity, demographics, and consumer behaviors: International market segmentation across product categories. International Marketing Review, 28(3), 244–266. Craig, C. S., & Douglas, P. S. (2006). Beyond national culture: Implications of cultural dynamics for consumer research. International Marketing Review, 23(3), 322–342. Craig, C. S., Douglas, P. S., & Bennet, A. (2009). Contextual and cultural factors underlying Americanization. International Marketing Review, 26(1), 90–109. Cutura, M. (2006). The impacts of ethnocentrism on consumer’s evaluation processes and willingness to buy domestic vs. imported goods in the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina. South East European Journal of Economics and Business, 1(2), 54–63. Deutskens, C. E., Ruyter, D. K., & Wetzels, M. G. M. (2006). An assessment of equivalence between online and mail surveys in service research. Journal of Service Research, 8(4), 346–355. De Mooij, M. (2004). Consumer behavior and culture: Consequences for global marketing and advertising. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Das and Mukherjee 51 Dmitrovic, T., Vida, I., & Reardon, J. (2009). Purchase behaviour in favor of domestic products in the West Balkans. International Business Review, 18(5), 523–535. Driedger, L. (1978). The Canadian ethnic mosaic. Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart. Forehand, R. M., Deshpande, R., & Reed, A. (2002). Identity salience and the influence of differential activation of the social self-schema on advertising response. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1086–1099. Fornell, C., & Larcker, F. D. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 382–388. Ger, G., & Belk, W. R. (1996). Cross-cultural differences in materialism. Journal of Economic Psychology, 17(1), 55–77. Ghosh, B. (2012). Globalisation and social transformation: Yogendra Singh on culture change in contemporary India. In M. Ishwar (Ed.), Modernization, globalization and social transformation (pp. 242–256). Jaipur, India: Rawat Publications. Graddol, D. (2000). The future of English. London: The British Council. Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hair Jr, J. F., Lukas, B. A., Miller, K. E., Bush, R. P., & Ortinau, D. J. (2014). Marketing research (4th ed.). North Ryde, NSW: McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Limited. Hirschman, E. C. (1981). American Jewish identity: Its relationship to some selected aspects of consumer behaviour. Journal of Marketing, 45, 102–110. Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Hui, M. K., Annamma, J., Kim, C., & Laroche, M. (1992). Acculturation as a determinant of consumer behavior: Conceptual and methodological issues. In C. T. Allen, T. J. Madden, T. A. Shimp, R. D. Howell, G. M. Zinkhan, D. D. Heisley, R. J. Semenik, P. Dickson, V. Zeithaml, & R. L. Jenkins (Eds.), Marketing Theory and Applications (pp. 466– 473). Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association. Jain, S. K., & Jain, R. (2013). Consumer ethnocentrism and its antecedents: An exploratory study of consumers of India. Asian Journal of Business Research, 3(1), 1–18. Javalgi, R., Khare, V., Gross, A., & Scherer, R. (2005). An application of the consumer ethnocentrism model to French consumers. International Business Review, 14(3), 325–344. Kim, S. Y., & Chao, R. K. (2009). Heritage language fluency, ethnic identity, and school effort of immigrant Chinese and Mexico adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(1), 27–37. Kim, Y.Y. (2015). Finding a “home” beyond culture: The emergence of intercultural personhood in the globalizing world. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 46, 3–12. Klein, J. G., Ettenson, R., & Krishnan, B. C. (2006). Extending the construct of consumer ethnocentrism: When foreign products are preferred. International Marketing Review, 23(3), 304–321. Laroche, M., Kim, C., Hui, M., & Joy, A. (1996). An empirical study of multidimensional ethnic change: The case of the French-Canadians in Quebec. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27(1), 114–131. Laroche, M., Kim, C., Tomiuk, M. A., & Bélisl, D. (2005). Similarities in Italian and Greek multidimensional ethnic identity: Some implementation in food consumption. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 22(2), 143–163. Li, J., Marbley, A. F., Bradley, L., & Lan, W. (2016). Attitudes toward seeking counseling services among Chinese international students: Acculturation, ethnic identity, and language proficiency. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 65–76. Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. Lindridge, A. (2010). Are we fooling ourselves when we talk about ethnic homogeneity? The case of religion and ethnic sub-divisions amongst Indians living in Britain. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(5/6), 441–472. Lysonski, S. (2014). Receptivity of young Chinese to American and global brands: Psychological underpinnings. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(4), 250–262. Lysonski, S., & Durvasula, S. (2013). Nigeria in transition: Acculturation to global consumer culture. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(6), 493–508. 52 Management and Labour Studies 45(1) Lysonski, S., Durvasula, S., & Madhavi, D. A. (2012). Evidence of a secular trend in attitudes towards the macro marketing environment in India: Pre and post economic liberalization. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(7), 532–544. Malhotra, K. N., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Common method variance in is research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science, 52(12), 1865–1883. Mendoza, R. H. (1989). An empirical scale to measure type and degree of acculturation in Mexican–American adolescents and adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 20(12), 372–385. Okechuku, C. (1994). The importance of product country of origin: A conjoint analysis of the USA, Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands. European Journal of Marketing, 28(4), 5–19. Özsomer, A. (2012). The interplay between global and local brands: A closer look at perceived brand globalness and local iconness. Journal of International Marketing, 20(2), 72–95. Peñaloza, L. (1994). Atravesando fronteras/border crossings: A critical ethnographic exploration of the consumer acculturation of Mexican immigrants. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 32–54. Pentz, C., Terblanche, N., & Boshoff, C. (2015). Antecedents and consequences of consumer ethnocentrism: Evidence from South Africa. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 12(2), 199–218. Phinney, J. S., Horenczyk, G., Liebkind, K., & Vedder, P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An international perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 493–510. Pires, G., & Stanton, J. (2000). Marketing services to ethnic consumers in culturally diverse markets: Issues and implications. Journal of Services Marketing, 14(7), 607–618. Pires, D. G., & Stanton, J. P. (2010). Ethnicity and acculturation in a culturally diverse country: Identifying ethnic markets. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 2010, 42–57. Pires, D. G., Stanton, J. P., & Cheek, B. (2003). Identifying and reaching an ethnic market: Methodological issues. Qualitative Market Research, 6(4), 224–235. Rahman, H. Md., Morshed, M., & Takdir, M. (2011). Identifying and measuring consumer ethnocentric tendencies in Bangladesh. World Review of Business Research, 1(1), 71–89. Raikhan, S., Moldakhmet, M., Ryskeldy, M., & Alua, M. (2014). The interaction of globalization and culture in the modern world. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 122, 8–12. Reardon, J., Miller, C., Vida, I., & Kim, I. (2005). The effects of ethnocentrism and economic development on the formation of brand and ad attitudes in transitional economies. European Journal of Marketing, 39(7/8), 737–754. Renko, N., Karanovic, B. C., & Matic, M. (2012). Influence of consumer ethnocentrism on purchase intentions: Case of Croatia. Retrieved from http://hrcak.srce.hr/file/138614 Richins, L. R. (2004). The material values scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 209–219. Richins, L. R., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. Rosenthal, D. A., & Cichello, A. M. (1986). The meeting of two cultures: Ethnic identity and psychological adjustment of Italian–Australian adolescents. International Journal of Psychology, 21(4–5), 487–501. Saxena, R. (2010). The middle class in India: Issues and opportunities. Deutsche Bank Research. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.616.3527&rep=rep1&type=pdf Sharma, S., Shimp, T. A., & Shin, J. (1995). Consumer ethnocentrism: A test of antecedents and moderators. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(1), 26–37. Shimp, T. A., & Sharma, S. (1987). Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 280–289. Sobol, K., Cleveland, M., & Laroche, M. (2018). Globalization, national identity, biculturalism and consumer behavior: A longitudinal study of Dutch consumers. Journal of Business Research, 82(1), 340–353. Strizhakova, Y., Coulter, R., & Price, L. (2012). The young adult cohort in emerging markets: Assessing their glocal cultural identity in a global marketplace. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 43–54. Sumner, W. (1906). Folkways. Boston, MA: Ginn. Supphellen, M., & Grønhaug, K. (2003). Building foreign brand personalities in Russia: The moderating effect of consumer ethnocentrism. International Journal of Advertising, 22(2), 203–226. Das and Mukherjee 53 Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Person Education. Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories: Studies in social psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33, 47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. Tantray, S. (2018). Consumer ethnocentrism in 21st century: A review and research agenda. Business and Economics Journal, 9(3), 368–380. Thomas, B., Fomby, R., Carter, H., & Johnson, R. S. (1984). Advanced econometrics methods (pp. 225–228). New York, NY: Springer Verlag. Trimble, J. E. (2003). Introduction: Social change and acculturation. In K. Chun, M. Organista, P. Balls, & M. Gerardo (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 3–13). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. Vida, I., & Fairhurst, A. (1999). Factors underlying the phenomenon of consumer ethnocentricity: Evidence from four central European countries. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 9(4), 321–337. Vida, I., Dmitrović, T., & Obadia, C. (2008). The role of ethnic affiliation in consumer ethnocentrism. European Journal of Marketing, 42(3/4), 327–343. Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (2004). Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of Brand Management, 11(6), 484–506. White, L. C., & Burke, P. (1987). Ethnic role identity among White and Black college students: An internationalist approach. Sociological Perspective, 30(3), 310–331. Wiseman, R. L., Hammer, M. R., & Nishida, H. (1989). Predictors of intercultural communication competence. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 13(3), 349–370. Woodside, A., & MacDonald, R. (2012). Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. Journal of Business Research, 66(4), 463–472. Yaprak, A. (2008). Culture study in international marketing: A critical review and suggestions for future research. International Marketing Review, 25(2), 215–229. Zarkada-Fraser, A., & Fraser, C. (2002). Store patronage prediction for foreign-owned supermarkets. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 30(6), 282–299. Zhang, J., & Shavitt, S. (2003) Cultural values in advertisements to the Chinese x-generation: Promoting modernity and individualism. Journal of Advertising, 32(1), 23–33.