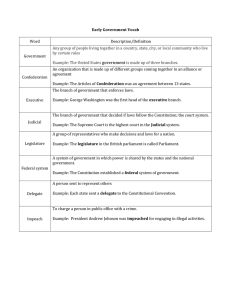

LAW314: CONSTITUTIONAL LAW TABLE OF CONTENTS CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION 5 5 6 7 7 EARLY FEDERAL DOCTRINES: 1903-1920 8 AMALGAMATED SOCIETY OF ENGINEERS V ADELAIDE STEAMPSHIP CO LTD (ENGINEERS CASE) (1920) 28 CLR 129 9 CHARACTERISATION 11 TEXTUALISM ORIGINALISM PROGRESSIVISM NATIONAL V FEDERAL EXTERNAL AFFAIRS POWER – S 51(XXIX) 13 GEOGRAPHIC EXTERNALITY IMPLEMENTING TREATIES CONFORMING TO THE TREATY TEST TO BE APPLIED IN EXAM 13 14 18 19 CORPORATIONS POWER – S 51(XX) 20 WHAT IS A CORPORATION – THE REACH OF S 51(XX) WHAT ASPECT OF THE CORPORATION CAN BE REGULATED – THE SCOPE OF S 51(XX) WHICH ‘PERSONS’ CAN S 51(XX) EXTEND TO REGULATE NSW V COMMONWEALTH (WORKCHOICES CASE) (2006) 321 ALR 1 TEST TO BE APPLIED IN EXAM 20 22 25 26 29 FEDERALISM: STATE CONSTITUTIONS AND INCONSISTENCY 30 STATE CONSTITUTIONS INTERPRETATION OF INCONSISTENCY COMMONWEALTH V ACT (SAME-SEX MARRIAGE CASE) (2013) 250 CLR 441 TEST TO BE APPLIED IN EXAM 30 30 32 34 34 35 36 39 41 FEDERALISM: FINANCIAL RELATIONS, EQUAL TREATMENT AND INTERSTATE TRADE 42 FEDERALISM ARGUMENTS IN FAVOUR OF FEDERALISM ARGUMENTS AGAINST FEDERALISM 42 42 43 43 43 44 44 45 47 48 NSW STATE SOVEREIGNTY FEDERALISM IN THE CONSTITUTION INCONSISTENCY BETWEEN STATE AND FEDERAL LAWS TYPES OF INCONSISTENCY CHARACTERISTICS OF AUSTRALIAN FEDERALISM FEDERAL V NATIONAL CHARACTER OF THE CONSTITUTION EQUAL TREATMENT PROVISIONS UNDER THE TAXATION POWER UNDER THE TRADE AND COMMERCE POWERS UNDER THE RIGHTS OF RESIDENTS IN STATES FREEDOM OF INTERSTATE TRADE – S 92 2 TEST TO BE APPLIED IN EXAM 51 EXECUTIVE POWER 53 PREROGATIVE POWER SCOPE OF S 61 PAPE V COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION (2009) 238 CLR 1 WILLIAMS V COMMONWEALTH (2012) 248 CLR 156 53 54 55 56 57 57 60 JUDICIAL POWER 64 CHAPTER III JUDGES TEST TO BE APPLIED IN EXAM 64 64 65 66 67 68 68 72 82 EXPRESS RIGHTS AND A BILL OF RIGHTS 84 PROTECTION OF RIGHTS HOW 84 84 84 85 90 90 91 92 93 93 94 NATIONHOOD POWER APPROPRIATIONS AND SPENDING NATIONHOOD AND CONTRACTING JURISDICTION OF THE HIGH COURT WHAT IS JUDICIAL POWER R V KIRBY; EX PARTE BOILERMAKERS’ SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA (1956) 94 CLR 254 LIMBS DRAWN FROM BOILERMAKERS LIMB 1: THE JUDICIAL POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH CAN ONLY BE VESTED IN A CHAPTER III COURT LIMB 2: CHAPTER III COURTS CAN EXERCISE ONLY THE JUDICIAL POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH AMENDMENT PROPOSALS MODELS OF HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTIONS FREEDOM OF RELIGION MEANING OF RELIGION MEANING OF A LAW ‘FOR PROHIBITING THE FREE EXERCISE’ OF ANY RELIGION MEANING OF A LAW ‘FOR ESTABLISHING ANY RELIGION’ TRIAL BY JURY INTERPRETATION OF S 80 BILL OF RIGHTS NSW PARLIAMENT STANDING COMMITTEE ON LAW AND JUSTICE, A NSW BILL OF RIGHTS (17 OCTOBER 2001) PARLIAMENTARY PAPER, NO 893, CHAPTERS 5 AND 6 94 IMPLIED RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS 110 IMPLIED RIGHT TO VOTE LIMITATIONS ON THE RIGHT TO VOTE STRUCTURALISM IMPLIED FREEDOM OF POLITICAL COMMUNICATION TEST TO BE APPLIED IN EXAM 110 111 112 114 120 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF AUSTRALIA 121 MABO AND SOVEREIGNTY 121 122 123 124 124 DIFFICULTIES IN ESTABLISHING NATIVE TITLE ONGOING INFLUENCES THE RACE POWER, INDIGENOUS RECOGNITION AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE THE RACE POWER 3 INDIGENOUS RECOGNITION AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE 126 EXAM HINTS 129 HYPOTHETICAL PROBLEM TOPICS ESSAY TOPICS 129 129 Sources: Gerangelos et al (eds), Winterton’s Australian Federal Constitutional Law: Commentary and Materials (Thomson Reuters, 3rd ed, 2013). Harvey et al, LexisNexis Study Guide: Constitutional Law (LexisNexis, 2nd ed, 2014). Joel Harrison’s 2017 lecture slides. Topic summaries found online via google 4 CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION TEXTUALISM There are two forms of textualism for the purposes of interpreting the Constitution: 1. Literalism 2. Legalism LITERALISM - Involves a natural/literal reading of just the words. Considers words to be unambiguous, without a need to refer to external texts. Literal readings may be contrary to purpose. It ignores the intentions of framers. LEGALISM - Involves consideration of the text as well as legal context. Like literalism, it ignores the intentions of framers. Explanation in Engineers case - - It is the duty of the Court to turn its earnest attention to the provisions of the Constitution itself. That instrument is the political compact of the whole of the people of Australia enacted into binding law by the Imperial Parliament, and it is the chief and special duty of the Court faithfully to expound and give effect to it according to its own terms, finding the intention from the words of the compact, and upholding it throughout precisely as framed.’ [142] It must be read ‘naturally in light of the circumstances in which it was made, with knowledge of the combined fabric of the common law, and the statute law which preceded it.’ [152] Rationale: 1. Rule of law and accessibility: we want to know what the Constitution says because it is a fundamental text. The law should be accessible and people should be able to understand it. 2. Constitutional division of powers: representative government, foundational decisions, allows amendment power. Swearing in of Sir Owen Dixon as Chief Justice (1952) 85 CLR xi, xiii-xiv: ‘the court’s sole function is to interpret a constitutional description of power or restraint upon power and say whether a given measure falls on one side of a line consequently drawn or on the other, and that it has nothing whatever to do with the merits or demerits of the measure. … to be excessively legalistic. I should be sorry to think that it is anything else. There is no other safe guide to judicial decisions in great conflicts than a strict and complete legalism.’ 5 ORIGINALISM This form of interpretation requires you to discover and apply the originally understood meaning of the Constitution’s terms and provisions. It is argued that such meaning relates to what was intended at the time. Cole v Whitfield (1988) 165 CLR 360 - Debated the meaning of ‘absolutely free’ in s92, which says that ‘trade, commerce and intercourse among the States…shall be absolutely free’. Decided at 385 that the court could look to Convention debates (original understanding) but not to substitute the meaning of words or to appeal against subjective intentions of framers. Theophanous v Herald & Weekly Times Ltd (1994) 182 CLR 104, 196: - McHugh J: ‘The true meaning of a legal text almost always depends on a background of concepts, principles, practices, facts, rights and duties which the authors of the text took for granted or understood, without conscious advertence, by reason of their common language or culture.’ CONVENTIONAL UPDATING AND INCREMENTAL ACCOMMODATION - - This remains compatible with originalism because the words are understood as accommodating and incorporating later developments and meanings. This approach is characterised by a connotation-denotation divide: the connotation of a word is fixed (its essential meaning); its denotations change with new instances. The Constitution expresses ‘concepts and purposes … at a sufficiently high level of abstraction to enable events and matters falling within the current understanding of those concepts and purposes to be taken into account.’ (Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally (Cross-vesting Case) (1999) 198 CLR 511, 552 McHugh J) To avoid being ‘slaves to the mental images and understandings of the founding fathers and their 1901 audience, a prospect which they almost certainly did not intend’ (Eastman v The Queen (2000) 203 CLR 1, 50 McHugh J) Grain Pool of Western Australia v Commonwealth (2000) 202 CLR 479 - - Considered s 51 (xviii) ‘Copyrights, patents of inventions and designs, and trade marks’whether this extended to the statutory recognition of ‘plant variety rights’, a novel form of intellectual property. Decided that framers were aware of scientific developments and its potentials. 6 Singh v Commonwealth (2004) 222 CLR 322 - There may be central characteristics but the Constitution’s application changes over time. Trial by jury - This was not mentioned in the Singh but consider the changing right to trial by jury in s 80given Singh’s reasoning. It now extends to women jurors despite inability to sit in 1901. Seen as falling within the essential characteristics of a jury. PROGRESSIVISM This form of Constitutional interpretation is critical of connotation-denotation divide. Instead, it argues that we update the constitution to accommodate changing cultures and sense of justice. The Role of the Court - - Brownlee v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 278 [105] Kirby J: ‘the text of the Constitution must be given meaning as its words are perceived by succeeding generations of Australians, reflected in this Court [as representations of succeeding generations] …’ Courts given authority to do this under the theory of popular sovereignty: Theophanous v Herald & Weekly Times Ltd (1994) 182 CLR 104, 172 - Deane J: the Const derives its authority from its ‘acceptance by the people’, meaning it should not be construed on the basis of the ‘dead hand’ of the framers, but rather in terms of it being a ‘living instrument of its vitality and its adaptability to serve succeeding generations’ Moralistic Rationale - Progressivism may be based on moral accounts. For example, deciding whether the ‘race power’ can only be used for the benefit of indigenous persons or potentially for their detriment- Kartinyeri v Commonwealth 195 CLR 337 (1998). NATIONAL V FEDERAL Issue: does the Constitution have a federal or national character? It refers to ‘the people’ and ‘the people of the states’. Federalism: a system of government where power is divided between parts (states) and the central government (Cth). 7 Federal characteristics - Equal representation for founding states within the Senate: s7 States maintain those powers not given to the Commonwealth, and their constitutions continue. Pre exiting societies within continuing power ss106- 107. States play a heavy role in amendment: s128. National characteristics - Commonwealth law takes precedence over inconsistent state law: s109 S 117 Aimed at preventing a State and perhaps Commonwealth from discriminating against non-alien residents of other States. ‘Full faith and credit’ be given throughout Commonwealth to the ‘laws, the public Acts and records and the judicial proceedings of every State’: s118. ‘Trade, commerce and intercourse among the States shall be absolutely free’: s 92. Stephen Gageler, ‘Beyond the Text: A Vision of the Structure and Function of the Constitution’ (2009) 32 Australian Bar Review 138: ‘it appears to me incontrovertible that federation of the newly self-governing Australian colonies at the end of the nineteenth century was conceived not as a means of dividing and constraining government but as a means of empowering self-government by the people of Australia.’ EARLY FEDERAL DOCTRINES: 1903-1920 Includes: 1. Immunity of instrumentalities doctrine; and 2. Reserved State Powers Doctrine Note: these were not found in the text of the Constitution but implied from prior doctrines of federalism. IMMUNITY OF INSTRUMENTALITIES DOCTRINE Each governmental element of the federation (states, Cth gov) is immune from the laws of others. I.e. NSW cannot tax Vic gov employees; Cth cannot force NSW government to adopt certain workplace relations laws. D’Emden v Pedder (1904) 1 CLR 91 at [11] per Griffth CJ, Barton and O’Conner JJ: - [W]hen a State attempts to give its legislative or executive authority an operation which, if valid, would fetter, control, or interfere with, the free exercise of the legislative or executive power of the Commonwealth, the attempt, unless expressly authorized by the Constitution, is to that extent invalid and inoperative.’ Evidence in the Constitution 8 - It is not direct For example, section 114 provides for limited immunity against states or the Commonwealth taxing each other’s property. However, court held that broader immunity is implied because it was a necessary feature of federalism. RESERVED STATE POWERS DOCTRINE The states have certain legislative power ‘reserved’ to them. When interpreting Commonwealth power, a narrow interpretation is to be favoured, i.e. one that does not encroach upon residual powers of the states. States each have their own sphere of power, which Commonwealth can’t intrude. R v Barger (1908) 6 CLR 41 Facts: - Commonwealth imposed excise duties on various agricultural implements Provided that duties would not be imposed if remuneration for labour had been declared by the House to be fair or if pay was awarded according to an industrial award under the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act Issue: was the law with respect to ‘taxation’ as empowered by s 51(ii) of the Constitution? Decision: (3:2) no, the law made by the Commonwealth was not permitted by the Constitution. Reasoning: - The power of taxation was intended to be something entirely distinct from a power to directly regulate the domestic affairs of the States, which was denied to the Parliament It would be regulating labour/employment- a state matter. Evidence in the Constitution - - It is not direct It is an implied doctrine, there is no list of reserved powers. Any legislative power not specifically assigned to Commonwealth was reserved to the states. This was seen as necessary to the vision of federalism. The Court pointed to s 107- providing state power will ‘continue’ AMALGAMATED S OCIETY OF ENGINEERS V ADEL AIDE STEAMPSHIP CO LTD (ENGINEERS CAS E) (1920) 28 C LR 129 Facts: 9 - Engineers’ union lodged a claim for an award thus seeking to have Commonwealth industrial laws applied to a State employer Issue: Could a Commonwealth law made under the ‘conciliation and arbitration’ power (s51xxxv) validly apply to the State and thus the State employers? Decision: Yes, it could bind. Reasoning: 1. We are one nation with a common sovereign in the Empire, 2. We have responsible government. On responsible government - - ‘When the people of Australia, to use the words of the Constitution itself, “united in a Federal Commonwealth,” they took power to control by ordinary constitutional means any attempt on the part of the national Parliament to misuse its powers.’ (151) I.e. no implied doctrine was needed; constitutional interpretation should not take place against hypotheticals of abuse; inappropriate for the court to inquire into potential abuse – a political question (150) Impact and further reasoning 1. Shift in understanding of the Constitution: - The majority called the Constitution ‘the political compact of the whole of the people of Australia’ [142]. Note Griffith CJ’s personal view in the minority: that non-interference between government powers is assumed unless it was clearly granted [145]. 2. Shift towards a national conception of the Constitution - Responsible government aligns with the UK not US, leading to a national rather than federal conception [147]. 3. Shift in understanding about interpretation - Must apply ‘settled rules of construction’ [143] o Shift to legalism: turn to words and find their natural meaning without recourse to an external theory (such as that posed by Griffith CJ) [144]. o Read it naturally in light of circumstances with knowledge of common law and statute that preceded it [152]. o ‘give effect to it according to its own terms, finding the intention from the words of the compact, and upholding it throughout precisely as framed’ [142]. o Power is only limited where the statute in question violates an express condition placed on the provision in the Constitution [143]. o The Court noted s109 of Constitution: supremacy to all Commonwealth Acts even when the state Act relates to a matter passed under an ‘exclusive’ state power [155]. o In this case, persons representing the State were subject to the Commonwealth industrial power, unless there was an express condition or restriction in the Constitution. The relevant section was broad, extending ‘to all industrial disputes in fact extending beyond the limits of any one State’ thus no exception when a State itself was involved. 10 o I.e. no more implied immunities doctrine. Summary: - - - Overturned two doctrines: o Implied intergovernmental immunities doctrine; and o Reserved powers doctrine. These were derived from prior conceptions of federalism. It adhered to a textualist interpretative methodology. Commonwealth heads of power to be given natural reading (liberal, broad). Had the consequence of increasing the legislative power of the central government. Grants of legislative power are now to be read ‘with all the generality the words admit’ even if this means (because of s 109) that state power is reduced considerably. This ^ was justified by responsible government. C HARAC TERISATION Test for characterisation: 1. Examine the Federal law in question: a. What rights and duties does it create? b. What are its significant features? 2. Examine the head of power in question: a. What is the connotation and denotation used of the words and phrases used to describe the head of power? b. Connotation (central characteristic - Singh) and denotation (application). c. What is the ’core’ meaning and what is incidental to that core that is necessary to implement the power? d. What matters ‘incidental’ to that core can also be regulated? See Grain Pool of Western Australia v Commonwealth 3. Is the law a law ‘with respect to’ the head of power: a. evaluate the strengths of the connection to the head of power – practical and legal operation. b. Is there a sufficient connection? (This is a question of fact and not merely whether the means are necessary or desirable). See Grain Pool of Western Australia v Commonwealth (2000) 11 Constitutional Law Problem Question Is there a C’th Law? The Race Power Trade and Commerce Power Subject Matter Power Characterize that law What does the act actually do? Corporations Power External Affairs Nationhood Physically External International Relations Treaties Implied incidental power Purposive Power Is the law Sufficiently connected to the subject matter? Is the law reasonably and appropriately adapted? Territories Grants Can be conditional Conditions may be enforced Plenary Power Acceptance cannot be enforced Gross Valid 12 EXTERNAL AFFAIRS POW ER – S 51(XXIX) Section 51(xxix): The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: … external affairs. Applies to: - Treaties Matters of international concern Committee between nations GEOGRAPHIC EXTERNALITY There has been a general agreement in the Court’s interpretation of the external affairs power that a law will be one with respect to this constitutional head of power where the matter is external to Australia – mere geographic externality is sufficient. Polyukhovich v Commonwealth (the War Crimes Case) (1991) 172 CLR 501 Facts: - S 9 of the War Crimes Act 1945 (Cth) provided for trial and punishment of Australian citizens and residents who might have committed war crimes during WWII At the time of the alleged crimes, the pl was not a resident or citizen of Australia Issue: Does the external affairs power extend to all persons, matters or things ‘external’ to Australia, regardless of a factual nexus or relationship to Australia? Held: Yes Reasoning: - ‘If a place, person, matter or thing lies outside the geographical limits of the country, then it is external to it and falls within the meaning of the phrase ‘external affairs’ Under the natural reading of the Constitution Geographic externality is sufficient Dissent: - Brennan J: ‘the affairs which are the subject matter of the power are…the external affairs of Australia; not affairs which have nothing to do with Australia … there must be some nexus, not necessarily substantial’ 13 - Toohey J: adopted similar view to Brennan J Victoria v Commonwealth (the Industrial Relations Act Case) (1996) 187 CLR 416 Confirmed majority view in War Crimes Case – even the dissenters in the War Crimes Case aligned with the majority in this case. Effectively determined that geographical externality is sufficient. Horta v Commonwealth (1994) 181 CLR 183 Facts: - Petroleum (Australia-Indonesia Zone of Co-operation) Act 1990 (Cth) implemented treaty between the parties Permitted and regulated petroleum exploitation in the Timor Gap. Issue: whether legislation implementing a treaty between countries permiting and regulating petroleum exploitation in the Timor Gap was valid under s 51(xxix). Held: Yes Reasoning: - - A law will be prima facie within the external affairs power if: 1. The matter is geographically external to Australia; and 2. Parliament recognises the matter as affecting Australia Requirements were established regarding treaties, however the external affairs character applies regardless of the treaty because the matter is geographically external Even if the Treaty were contrary to international law it would still come under the external affairs power – because it is external to Australia Emphasis on geographic externality requirement XYZ v Commonwealth (2006) 227 CLR 532 Facts: - Ss 50BA and 50BC of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) rendered it an offence for an Australian citizen or resident, while outside Australia, to engage in sexual intercourse with, or commit an act of indecency on, a person under the age of 16yo Issue: whether geographic externality was enough/was there an additional element required? Held: Yes Reasoning: Geographic externality is sufficient IMPLEM ENTING TREATIE S International treaties entered into by Australia have no legal effect unless they are then implemented in Australia through normal statutes. The external affairs power therefore enables the Commonwealth 14 Parliament to legislate laws in attempt to implement an international treaty entered into by Australia. This raises the questions of what are the limitations of this power and what relationship must exist for it to come into effect. Questions arose, however, in relation to whether the power to legislate under s 51(xxix) was limited to those treaties which dealt with particular subject matters – as opposed to those which deal with other particular subject matters. Is there a criterion for determining a matter of external affairs? R v Burgess; Ex parte Henry (1936) 55 CLR 608 Facts: - Australia had entered an international convention regarding airspace safety. A Commonwealth Act gave the Governor General the power to revoke give and revoke licenses (and prohibit flying without them) Henry was a (domestic) pilot who flew his plane after his license was revoked Issue: The question was whether the external affairs power could be relied on because this was an implementation of a treaty, even though the subject matter was inherently domestic. Alternatively, the issue could be termed as: whether implementing treaties had to be concerned with matters of external relations. Held: Parliament is empowered to make laws which implements treaty terms regarding any matter – it does not have to be external. However, the treaties must be entered into bona fide (as opposed to being a mere excuse to engage in a power), and must comply with the constitutional limits and guarantees. Dissent: - Stark J: the matter must be of sufficient international significance to make it a legitimate subject for international co-operation and agreement Dixon J: it would be an ‘extreme view’ to permit Executive to enter into treaty on purely an ‘internal concern’ and then regulate the conduct of citizens based on that obligation Koowarta v Bjelke-Peterson (1982) 153 CLR 168 Facts: - Qld Minister refused to grant required consent to transfer the lease sought by Aboriginal Land Fund Commission at Koowarta’s request and other members of an indigenous group Refused because a Qld State government policy not to favourably view proposals to acquire large areas of additional land for development by Aboriginals Koowarta challenged decision arguing breach of Racial Discrimination Act – s 9(1) provided it was unlawful for a person (e.g.) to restrict the exercise, on an equal footing, of any human right; s 12 (1) made it unlawful to refuse to dispose of any land ‘by reason of race’ Issue: were the RDA provisions within the scope of s 51(xxix)? Held: Yes; using Stephen J’s judgment as the ratio for this case: implementing a treaty with respect to EA powers requires a notion of ‘international concern’ 15 Reasoning: - - - Mason J: o EA power extends to legislating for ratification and for implementing obligations o Cannot evade constitutional prohibitions (e.g. discriminatory treatment against States, amendment other than by s 128) o Cannot inhibit continuing obligations or their capacity to function o There is no subject matter of limitation, because: 1. The Constitution draws no distinction where the matte operates domestically: powers should be construed liberally, increased power to the Commonwealth is the policy of EA power, connotation of EA hasn’t changed but its application to expanding internationalism has as expansion is necessary to participate in world affairs (Murphy J similarly says we would be an international cripple if treaty implementation required federal and state legislation) 2. Internal and external issues are not mutually exclusive: the State’s argument falsely assumes that matters internal and external are mutually exclusive, or that the vision can be judged by the Court. Brennan J: 1. A particular subject must affect or be likely to affect Australia’s relations with other international persons. Matters of Australia’s internal legal order can do this. 2. By accepting a treaty obligation, extending to Australia’s internal legal order, the subject of that obligation automatically attaches to the notion of being an external affair 3. There must be conformity between the provisions of the Statute and the Convention obligation. If not, the matters themselves must relate to the subject matter of ‘external affairs’. Stephen J: o To be ‘external’ – must relate to other nations or other things or circumstances outside of Australia o Unlike a grant of power over treaties, external affairs means the Court must examine ‘the subject matter, circumstance and parties’ o A treaty must be of concern to the ‘relationship between Australia and that other country … or of general international concern’ o Defines matters of international concerns as those that possess the ‘capacity to affect a country’s relations with other nations’ – determined by community of nations o Said that racial discrimination has become a matter of international concern Dissent: - Gibbs CJ: o Adopting an expansive view leads to an expansive power o Provisions are purely domestic therefore cannot possibly qualify as an external affair o Considers ‘external affairs’ to refer to matters concerning other countries 16 o Says the matter must be international in character: must involve relationships with other countries/things/people outside Australia Commonwealth v Tasmania (Tasmanian Dam Case) (1983) 158 CLR 1 Facts: - World Heritage Convention ratified by Australia in August 1974 – focused on preservation of heritage sites In 1981, the Commonwealth submitted three sites for listing on the World Heritage List Before listing was complete, the Tasmanian Parliament passed a law authorising construction of a dam on Gordon River (part of listing) Commonwealth Parliament passed World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983 (Cth) allowing the Governor-General to declare protected land Issues: 1. Is the relevant law a law with respect to the external affairs power? 2. What counts as an international concern? 3. Is federal balance a concern? Held: 1. Yes, based on Koowarta 2. Mason J: mere existence of a treaty is sufficient 3. No. Reasoning: External affairs power: Based on Koowarta, the external affairs power extends at least to implementing treaties where the subject matter is of international concern, or of concern to the relationship between Australia and other parties. What counts as an international concern? - - Mason J: o This is satisfied by the mere existence of a treaty/convention o While in 1900 matters of international concern might have been limited, now there ‘are virtually no limits to the topics which may become the subject of international cooperation and international conventions’ o The Court cannot decide what is and isn’t international concern – this would be second-guessing Parliament Gibbs CJ (dissenting): o Protection of the environment and cultural heritage does not affect our relationship with other nations – believes that legislation is relating to a purely domestic matter Is federal balance a concern? - Mason J: 17 o - Interpretive method: mere expectations of federal balance held in 1900 could not form a satisfactory basis for departing from the natural interpretation of te words used in the Constitution o Purpose of power: referred to Koowarta – framers might have expected a more limited reach but the underlying purpose was to enable the Commonwealth to act in external affairs – thus external affairs is an enduring power that must respond to the increasing internationalism o Constraining the power would have negative consequences Gibbs CJ (dissenting): o The division of power would be meaningless if the Cth could enter into treaties on matters of domestic concern and enlarge legislative powers so that they embrace all the field of activity CONFORMING TO THE TREATY The Court applies a proportionality standard: the law must be reasonably adapted and appropriated to the purpose of fulfilling an international obligation. If the law doesn’t have the character of a measure implementing the treaty or has a provision substantially inconsistent with the treaty, then it will be invalid – where certain provisions are invalid, these may be severed. 1. The Act must prescribe a regime that the treaty has ‘defined with sufficient specific to direct the general course to be taken by the signatory states’ (Industrial Relations Case o This does not need total precision but it needs sufficient specificity 2. The legislation must reflect a ‘faithful pursuit’ of the treaty’s purpose (Burgess; Tasmanian Dam Case) o The law must be appropriate and adapted or reasonably considered to be (Tasmanian Dam Case; Industrial Relations Case) o This requires a judicial evaluation of the initiatial legislative deicison o Pursuing an extreme course bight be relevant (Tasmanian Dam Case) o Must be ‘sufficiently stampted’ with the purpose of the Convention (Burgess; Tasmanian Dam) 3. Are the provisions inconsistent with the Treaty? o Not looking to see if legislation falls within the subject matter of external affairs o Looking to see if legislation falls within the treaty, which itself is the category that falls under the subject matter of external affairs (Industrial Relations Case) o For example: Deane J in Tasmanian Dam Case: ‘many provisions of the Act were not appropriate and adapted o Need not comply with all obligations under the treaty unless the legislation also presents privisons inconsistent with the obligations o ‘A law will be invalid if the deficiency is so substantial as to deny the law the character of a measure implementing the Convention or it is a deficiency which, when coupled 18 with other provisions of the law, makes it substantially inconsistent with the Convention (Industrial Relations Case) TEST TO BE APPLIED I N EXAM 1. Is the subject-matter of the Act relating to a matter which is geographically external to Australia? (look at geographic externality section) a. If yes – supported by s 51(xxix) b. If no, and instead relates to the domestic enactment of a treaty obligation – refer to question 2 2. Is the Act an enactment of a Treaty? (look at implementing a treaty section) a. Is the subject matter of international concern? i. Originally believed that international concern would be satisfied if the matter affected the relationship between Australia and other nations (Koowarta); however now understood a Treaty it will automatically be of international concern (Tasmanian Dam) as it is the role of a separate arm of government to determine whether a treaty is worthy of signature, not the Court. b. If yes, is it appropriate and adapted to the provisions of the treaty? Are the provisions consistent with the treaty (look at conformation with treaty section) 3. Is the Act inconsistent with any other limitations provided under the Constitution – i.e. requirement that Commonwealth does not discriminate against a particular State (Victoria v Commonwealth) or requirement for referendum to amend (s 128). 19 CORPORATIONS POWER – S 51(XX) Section 51(xx): The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: … foreign corporations, and trading or financial corporations formed within the limits of the Commonwealth. WHAT IS A CORPORATIO N – THE REAC H OF S 51(XX) The corporations power extends only to corporations ‘formed within the limits of the Commonwealth.’ The word ‘formed’ describes corporations which have been or shall have been created in Australia. This means that the Commonwealth does not have the general power to regulate formation of those corporations (Huddart, Parker & Co v Moorehead, confirmed in The Incorporation Case). However, the Commonwealth may incorporate companies as a matter incidental to other heads of power (Strickland v Rocla Concrete Pipes) – i.e. Australian National Airways v Commonwealth (No 1) held that the Commonwealth could incorporate a company under s 51(i) to conduct interstate trading business, as well as under incorporate companies in Territories pursuant to s 122. ‘Foreign corporations’: Defined as ‘corporations formed outside the limits of the Commonwealth’ (NSW v The Commonwealth (The Incorporation Case)) ‘Trading or financial corporations’: In order to determine whether a corporation is a trading or financial corporation as under the constitutional head of power, the courts have considered two tests: 1. The Activities Test: (Adamson’s Case) - This is the primary test used by the Court - This looks at the overall activities of the corporation, such as sources of income and profit. - Under the Adamson’s Case it was determined that to satisfy the activities test, trading must form a ‘significant proportion’ of the corporation’s overall activities o Mason J stated that it was important to distinguish between ‘significant’ as opposed to ‘incidental or slight’ 2. The Purpose Test: - The purpose of the corporation - This can be determined by looking to the corporation’s Constitution in order to determine the overall purpose that the corporation was established for 20 - However, it is important to note that this can be misleading in many circumstances because many corporations may seek to claim a different purpose for establishment in order to avoid liability for measures such as income tax etc. The Court has shown a general preference towards the Activities Test, however Queensland Rail [2015] demonstrated that the preferred approach is to instead use both tests in conjunction and examine both features of the corporation. R v FC of Australia; Ex parte WA National Football League (Adamson’s Case) (1979) 143 CLR 190 Issues: 1. Was the football club a trading corporation? 2. What degree of activity made a corporation a trading or financial corporation under the Activities Test? Held: 1. Yes 2. Mason J determined that the activities would have to be sufficiently significant in relation to the corporations overall activities, as opposed to ‘so slight and incidental’ – i.e. where churches or schools engage in some trading activities however its so slight and incidental that they cannot be considered a trading corporation. The issue of proportion required to satisfy the Activities Test was further settled in State Superannuation Board of Victoria v TPC where the majority held that the financial activities must form a substantial proportion of total activities, even if there are other more-extensive non-financial activities that take place. Reasoning: - Because a significant proportion of the club’s activities were dedicated to trading activities. Mason J referred to activities such as gate receipts, distribution of income against clubs, sources of income such as broadcasting, size of revenue Murphy J: so long as trading is not insubstantial, the fact that trading is incidental to other activities does not prevent it from being a trading corporation – trading need not be a dominant activity (reaffirmed in State Superannuation v TPC) Dissent: Stephen J used the Purpose Test and determined that the purpose of the club was to promote the game, and because there was no sharing of profits amongst the members it was not a trading corporation. Re Ku-Ring-Gai Co-Operative Building Society (No 2) (1978) 22 ALR 621 Issue: Whether a building society qualified as a financial corporation. Held: Yes Reasoning: 21 - - Brennan J stated that the ‘predominant activity is…borrowing of moneys to lend…lending of those moneys, receipt of repayments and the ultimate repayment of moneys to the source’, which qualifies as money dealings therefore financial activity Also, determined that the reason for incorporation did not matter, the purpose and culmination of their operations was more relevant. State Superannuation Board v TPC (182) 150 CLR 282 Issue: whether SSB was a financial corporation even though its function and intention for establishment was aimed at ‘public service’. Held: Yes Reasoning: - Mason, Murphy and Deane JJ: “corporation which engages in financial acitivities – deals in finances for commercial purposes”. Reaffirmed Murphy J’s reasoning in the Adamson’s Case On the issue of whether a manifestation of the Crown could be subject to the Corporations Power: Commonwealth v Tasmania (Tasmanian Dam Case) (1983) 158 CLR 1 Issue: whether the Hydro-Electric Commission was a trading or financial corporation for the purposes of s 51(xx). Held: Yes Reasoning: - Mason J (majority) stated that the connection with the government of a State does not take the corporation outside the power of s 51(xx). It is not a servant of the Crown, and whilst it has significant policy making roles and engages in large-scale construction, it still qualifies as a trading corporation on the basis of the Activities Test. WHAT ASPEC T OF THE C ORPORATION C AN BE REGU LATED – THE SCOPE OF S 51(XX) Over time the interpretation of s 51(xx) and its subsequent scope has gradually expanded to encompass a wider range of activities which may be regulated by s 51(xx). The original view: pre-Engineers Huddart, Parker & Co Pty Ltd v Moorehead (Huddart) (1909) 8 CLR 330 22 The HC applies the State reserved powers doctrine and held intrastate activities were reserved to States, therefore provisions regulating trade activities relating to intrastate trade were invalid under s 51(xx). Wider view: a power to regulate any trading or financial activities of the Constitutional Corporations. Strickland v Rocla Concrete Pipes Ltd (1971) 124 CLR 468 Issue: Were TPA provisions regulating intrastate trading activities/practices of trading/financial corporations supported by s 51(xx)? Held (on appeal): Yes – a law with respect to Constitutional Corporations is a law notwithstanding that it affects corporations in conduct of its intrastate trade (overturned Huddart) Reasoning: - The Reserved State Powers doctrine had been abolished by Engineers Wider again: a power to regulate the activities of persons which necessarily operate directly on the subject of the power – i.e. a power to regulate any activities of persons who impact the interests of s 51(xx) corporations. Actors and Announcers Equity Associations v Fontana Films Pty Ltd (Actors and Announcers Case) (1982) 150 CLR 169 Issue: whether provisions prohibiting secondary boycotts were supported by s 51(xx). Held: Yes Reasoning: - Gibbs J: Law that is directed at ‘conduct that is calculated to damage the trading activities of a trading corporation’ were within power Mason J: valid as a law with respect to a trading corporation because the law need not be limited to regulation of trading activities Commonwealth v Tasmania (the Tasmanian Dam Case) (1983) 158 CLR 1 Proposed that Corporations Power extends also to activities of trading corporations which are not directly trade activities however are engaged in for the purposes of trade. Issue: whether the corporations power extends to the regulation of activities of trading corporations, not being trading activities. Held: Yes Reasoning: - Mason J: o It would be unduly restrictive to confine the power to the regulation and protection of the trading activities, because the subject matter of the power is persons, not activities o The proposed restriction would deny Parliament power to regulate borrowing by trading corporations, despite the fact that the purpose of s 51(xx) was to enable the Parliament 23 - to regulate transactions between categories of corporations mentioned and the public – to protect the public, should the need arise o Rejected the Distinctive Character test (explained below) for three reasons: 1. The analysis has no applicability when looking at financial and foreign corporations – the scope of their power wasn’t to be limited by reference to the foreign aspects of foreign corporations and financial aspects of financial corporations 2. Fails to give effect to the principle that the legislative power conferred by the Constitution should be liberally construed 3. The power is attached to a designated type of legal person, this would seem ‘naturally to extend to their acts and activities’ o Conclusion: there is ‘no sound reason for denying that the power should extend to the regulation of acts undertaken by trading corporations for the purpose of engaging in their trading activities’. Deane J: o Draws on two points: 1. The relation of CP to other heads of power 2. Relation of CP to appropriate national power o The grant of power contained in s 51(xx) must not be read down by reference to any presumption that the various grants of power contained in s 51 should be construed as being mutually exclusive explained more in Work Choices Dissent: - Gibbs CJ: considered that many of the acts prohibited by the legislation were ‘preperatory to the trade’ – they were not concerned with trading corporations engaged in trading activities. Dawson J: expressed federalism concern: ‘the trading corporation etc were pegs upon which Parliament has sought to hand legislation on an entirely different topic’ – therefore reaching into what was typically a state based matter through the CP not through trading activities. The progression of the scope of s 51(xx) explored two tests: 1. The Distinctive Character Test - “the fact that the corporation is a foreign, trading or financial corporation should be significant in the way in which the law relates to it” if the law is to be valid [cf Dawson J in Tasmanian Dam Case] - Supported by Huddart and Concrete Pipes 2. The Object of Command Test - Essentially states that if the corporation is the object of command of the Act, it is enough to say that they can regulate any activity or person relating to or effecting that object of command. - Supported by Tasmanian Dam Case It is clear that the progression has led to the use of the Object of Command Test in preference to the Distinctive Character Test. 24 WHIC H ‘PERSONS’ CAN S 51(XX) EXTEND TO REGU LATE Once the Court considered that s 51(xx) supported the regulation of any person’s activities which directly impacted the trading activities of Constitutional Corporations, regardless of whether the impugned conduct tiself was trading conduct, it was necessary to determine to whom the regulations could extend – i.e. does the power extend to regulating the conduct of third parties? Re Dingjan; Ex parte Wagner (Dingjan) (1995) 183 CLR 323 Facts: Tasmanian Pulp contracted for Timber from Wagner, who subcontracted with Dingjan. When TP changed practices/requirements, W changed with D. D made an application for subcontract review under Industrial Relations Act 1988 (Cth) – the provisions of which say contract must relate to business of s 51(xx) corporation. Issues: Is there a sufficient connection between s 51(xx) corporation A and the subcontract between B and C for services which affect the business activities of A? Held: No Reasoning: - Brennan J: s 51(xx) may vary a contract between s 51(xx) and independent contractor, but not where the contract has no direct effect on the corporation McHugh J: As long as the law can be characterised as a law with respect to trading, financial or foreign corporations, Parliament can regulate many subject matters that are otherwise outside the scope of Commonwealth legislative power. However, the law must have a ‘relevance to or connection with’ a s 51(xx) corporation. It is not enough for the law to refer to the subject matter or to apply to the subject matter. o It must have significance to activities, functions, relationships or business i.e. give some benefit or detrimental effect o ‘A law operating on the conduct of outsiders will not be iwthin the power conferred by s 51(xx) unless that conduct has signficance’ for CC Dissent: - Gaudron J: this dissent was adopted in WorkChoices o S 51(xx) is ‘to be construed according to its terms and not by reference to unnecessary implications and limitations’ – rejecting concerns raised in several cases o CP extends to ‘the business functions, activities, and relationships of constitutional corporations’ and als ‘to the persons by and through whom they carry out those functions and activities with whom they enter into those relationships’ movement towards object of command test identifying CC as an object of command, once this is done, regulation can occur on any number of activities relating to its functions, activities and relations 25 o In this case: the provision in question either relates to being in a contract with the corporation or a party who is itself in a contract with the corporation NSW V COMMONW EAL TH (W ORKCHOICES CASE) (2006) 321 ALR 1 Facts: - Workplace Relations Amendment (Work Choices) Act 2005 (Cth) restructured workplace relations for ‘constitutional corporations’ – this affected 85% of workers Previously, Commonwealth legislations relied mostly on the conciliation and arbitration power s 51(xxxv) – whereas the Amending Act relied on s 51(xx) S 6 included in its definition of ‘employers’ constitutional corporations It aimed to create a national workplace relations system based on the s 51(xx) Five States and two unions brought an action seeking declaration that the Act was invalid Issues: 1. Could s 51(xx) be used to refashion the legislative regime that had previously depended on s 51(xxxv)? 2. Is a law requiring certain employee minimum entitlements in respect of constitutional corporations a ‘law with respect to such corporations’? Held: 1. Yes 2. Yes Questions asked by the Court: 1. Process of characterisation and interpretation: a. What degree of relevance or connection to ‘constitutional corporations’ is necessary for the characterisation as a law with respect to those corporations? The majority focused on the two different tests: 1. Distinctive Character Test This proposes that a law would only be a law with respect to the corporations power when ‘the fact that the corporation is a constitutional corporation should be significant in the way in which the law relates to it’. On this basis the Commonwealth could regulate in regard to trading activities or financial activities. Employment is not a matter of trading, therefore would fall outside the powers provided by s 51(xx). The majority rejected this test for three reasons: 26 - - It relied on previous cases which were fact specific and not relevant to the WorkChoices Case The Court must not interpret a power based on suspicion over the power’s future and potential use - this arose on the basis that the Plaintiff argued concerns around the effect of a broad interpretation It leaves serious risk of inverting the proper order of inquiry/constitutional interpretation post-Engineers. The proper order is to read the power broadly then ask whether the law significantly relates to the constitutional power, regardless of whether it encroaches on state power 2. Object of Command Test This test proposes that once you identify the CC, the Commonwealth is then empowered to regulate its relationships and any conduct – one of these is employment. It is irrelevant that employment is not a trading issue – you just need to identify a CC to then regulate its activities/relationships. The Court adopted this test because: - - The CP is a ‘persons power’ – ‘the power is to make laws with respect to particular juristic persons’ – which distinguishes it from a power ‘with respect to a function of government, a field of activity, or a class of relationships’ The Court adopted Gaudron J’s dissent in Dingjan to support this: ‘Power also extends to the persons by and through whom they carry out those functions and activities and with whom they enter into those relationships.’ b. What is the relevance of federal balance? The majority rejected arguments relating to federal balance because it would be an improper order of interpretation. c. Is the corporations power ‘read down’ by the limits within other powers? The Court determined that limits imposed on one power do not restrict the scope of another power. Strickland determined that the commerce power no longer restricts the corporations power, so why should the arbitration power? Dissent: Kirby J: Characterisation: - Characterised the law as being about industrial relations, which was derived from the Act’s object and the rights/liabilities it created. Callinan J agreed with this point Federal balance: - The constitution must be read in light of its federal character and design Interstateness preserved federal character of industrial relations law 27 Reading down: - Argued that by relying on s 51(xx) the Act is attempted to overcome a ‘safeguard, restriction or qualification’ in s 51(xxxv) You cannot make a law in reliance upon one subject matter when that law is properly characterised as one with respect to another head of power in circumstances where the latter power is afforded to the Federal Parliament ‘subject to a safeguard, restriction or qualification’ 2. Did the Convention Debates shed light on the meaning of the corporations power? Majority relied on the idea that the current disputed question was not on the framer’s minds. They supported a broad appeal to the corporations power, stating that the framers did not understand that corporations law was still in development in the 19 th century and could not have anticipated the boom of the corporate world in Australia’s present economy. Essentially the majority were arguing towards a national economy – it could be arguably better to have the power reside with the Commonwealth. Dissent: Callinan J pointed out two arguments from the Convention debates: 1. Any federal power relating to industrial affairs was to be confined to those of an interstate character. 2. Former colonies were to retain power over internal industrial disputes Kirby also drew on Convention Debates to say that the matter should remain in the power of States. 3. Was the failure to amend the Constitution (by referendum to provide for a general IR power relevant to interpreting the corporations power? In the past there had been six referendums proposing that the conciliation and arbitration power be extended to regulate employee and employer relationships – each of them failed. The majority determined that these failures were not relevant – the questions put to the electorate in each instance was not the same as that being considered in the case. Further, very few referendums succeed and therefore should not have too much weight (this seems like a poor argument – particularly in light of the fact that the Constitution is supposed to be a body of the people and therefore shouldn’t it be read in line with the general consensus of beliefs of the people as expressed in those referendums?) Dissent: Kirby J (Callinan J argued similarly): - Failure to amend relevant to limiting the CP – authority for Constitution is derived from the people, therefore repeat refusal must be relevant. 28 - The Constitution is grounded on a theory of popular sovereignty therefore should look to what the people say. Themes and Issues in WorkChoices: 1. Federalism - Kirby: “this Court needs to rediscover the federal character of the Constitution. It has been forgotten. Normatively it is a restraint on power. There has been a shift to ‘opportunistic federalism’ which would destroy the States and their express and implied role in the Constitution in a process of centralisation.” (note that the Court did revert back to Federalism in Williams under Executive Power week) - Callinan: the federal balance matters, we shouldn’t subjugate requirement that amendment happens by referendum. Reducing state powers is dangerous. 2. Impact of Engineers – interpretation is broad 3. Interpretation – originalism (Kirby, Callinan), textualism (majority), structuralist (Kirby – in discussions on federalism) 4. Consequences arising from the decision TEST TO BE APPLIED I N EXAM 1. Characterise the entity (Purpose Test vs Activity Test) 2. Characterise the Act (Distinctive Character Test vs Object of Command Test) (see WorkChoices for an analysis on the application of these Tests) a. Determine whether the law can regulate the entity based on the activities it is regulating and whether it has a direct impact on a s 51(xx) corporation. 29 FEDERALISM: STATE CO NSTITUTIONS AND INCO NSISTENCY STATE C ONSTITUTIONS Pre-1901 (federation) the States were self-governing British colonies – subject to the legal authority of the UK Parliament (this remained so until the Australia Act 1986 (Cth and UK)). At common law, the British colonies were classified as settles (this is relevant to the Mabo case), which meant that British common law applied upon settlement, insofar as suitable to the circumstances, and statutes applied when intended to apply ‘paramount force’. NSW Development: - Granted civil government in 1823 Established a Legislative Council – 5-7 members to advise the Governor The Governor to make any laws, subject to the requirement they not be ‘repugnant’ to the Laws of England Followed by growth in Legislative Council, and in 1842 – Australian Constitutions Act 1842 (UK) Governor, on advice of Council, given constituent power – power to alter constitution – and plenary power – power to pass laws for ‘the peace, welfare, and good government’ of the colony Constitution Act 1902 (NSW) Includes: - Responsible government (based ‘upon combination of law, convention, and political practice’ (Egan v Willis) Legislation dealing with organs of government Common law Commonwealth constitution (as it applies to the States) Arguably, the maintenance of representative democracy Representative democracy: Muldowney v South Australia (1996) 186 CLR 352, 377 (Gaudron J): - “it must be accepted following the decisions in Nationwide News and Australian Capital Television, that the States are not merely constituent elements of a federation, but constituent elements of a federal democracy. This, when considered in conjunction with the 30 subjection of the constitutions of the States to the Australian Constitution, requires that, in the interest of preserving the democratic nature of the federation, the States be and remain essentially democratic” Current legislative body of NSW: 1. Lower House – Legislative Assembly 2. Upper house – Legislative Council 3. The Queen – represented by the Governor ‘PEACE, WELFARE, AND GOOD GOVERNMENT’ Does this provide the State with unlimited legislative power? Section 5: The legislature shall, subject to the provisions of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, have power to make laws for the peace, welfare and good government of NSW in all cases whatsoever: … Provided that all Bills for appropriating any part of the public revenue, or for imposing any new rate, tax or impost, shall originate in the Legislative Assembly. Building Construction Employees and Builders’ Labourers Federation of NSW v Minister for Industrial Relations (BLF Case) (1986) 7 NSWLR 372 (NSWSC) - - - Words do not confer unlimited legislative power o Street CJ: ‘It appears to be generally assumed that these words confer unlimited legislative power, comparable with that vested in the English Parliament itself. I can find no satisfactory basis for that assumption. These words, by their very terms, confine the powers conferred to ‘peace, welfare, and good government’ of the body politic in respect of which the legislature is being established’ Argued some common law rights can be taken away o ‘It is arguable that some common law rights may go so deep that even Parliament cannot be accepted by the Courts to have destroyed them’ o ‘I do not think that literal compulsion, by torture for instance, would be within the lawful powers of the Parliament. Some common law rights presumably lie so deep that even Parliament could not override them’ (Taylor v NZ Poultry Board) Kirby rejected above ideas because we are protected by the Rule of Law: o ‘I do so in recognition of years of unbroken constitutional law and tradition in Australia and, beforehand, in the UK. That unbroken law and tradition has repeatedly reinforced and ultimately respected the democratic will of the people as expressed in Parliament’ o ‘A second protection lies in the power, referred to by Dicey, by which judges may construe legislation. In this sense, the sovereignty of Parliament is subject to the Rule of Law.’ 31 Parl’s Three Principles of Public Law 1. All taxation without consent of Parliament is illegal, 2. Consent of both Houses required for passage of legislation 3. Commons has right to inquire into and to amend abuses of Crown’s administration ancient constitution: power wrestled from an indivisible Crown Union Steamship Co of Australia Pty Ltd v King (1988) 166 CLR 1 - In reference to ‘peace, welfare, and good government’ It is a plenary power: a power as large as the Imperial Parliament, within limits prescribed by that Parliament Words don’t confer ability to strike down legislation on the ground that it does not promote peace, order or good government. Rather, these questions are for democratic politics. Issue: whether some common law rights run ‘so deep’ as to limit Parliament’s plenary and sovereign power. STATE SOVEREIGNTY HWR Wade, ‘The Basis of Legal Sovereignty’ [1955] CLJ 172, 174: 1. No Act of the sovereign legislature could be imvalid in the eyes of the courts and ‘it was always open to the legislature, so constituted, to repeal any previous legislation whatever’ 2. ‘therefore, no Parliament could bind its successors’ 3. The legislature had only one process for enacting sovereign legislation, whereby it as declared to be the joint Act of the Crown, Lords and Commons in Parliament assembled, and 4. In the case of conflict between two Acts of Parliament, the later repeals the earlier Question: can States be regards as sovereign? Commonwealth v New South Wales (1923) 32 CLR 200 (Isaacs, Rich and Starke JJ): - - No, not a foreign country o NSW is not a foreign country. The people of NSW are not, as are for instance, the people of France, a distinct and separate people from the people of Australia o When the Commonwealth is present in Court as a party, the people of NSW cannot be absent Dissent from Evatt J: ‘sovereign state’ is ambiguous o For ‘all purposes of self-government in Australia, sovereignty is distributed between the Commonwealth and the States’ 32 Twomey: Poses that perhaps sovereignty discussing is misplaced. What matters is distinguishing the different ‘Crown’ – i.e. Crown in right of Australia and Crwon in right of a State. The Crown in right of NSW has sovereignty in relation to the Territory of NSW and holds the radical title to that Territory. Hart: - Supreme legislative power is with the Queen in Parliament This is not alterable by common law There must be an ultimate sovereign or rule, and this is social, legal or political Can parliament limit its successors? This considers whether Parliament has continuing or self-embracing sovereignty as posed by Hart. There are different views: 1. Parliamentary sovereignty is a rule of common law. This gives certain inalienable rights. Though if sovereignty is fundamental, why are not other features? 2. Parliaments may restrict substance. 3. Parliaments can reconstitute itself for purposes of particular enactments (raises the question as to whether Parliament always means the same thing) Requirement: Manner and Form - Australia Act 1986 (Cth) s 2(2) o Gives all legislative power of the UK – continuing constituent power S 6: o ‘…[A] law made after the commencement of this Act by the Parliament of a State respecting the constitution, powers or procedure of the Parliament of the State shall be of no force or effect unless it is made in such manner and form as may from time to time be required by a law made by that Parliament, whether made before or after the commencement of this Act. o Maintains manner and form requirement; regulating continuing constituent power. This cannot be repealed or amended by a State Parliament- ss 5(b) and 15. o Applies to constitution, powers or procedures of the legislature. Thus not concerned with restrictive procedures (Goldsworthy) for ordinary legislation. ▪ Restrictive procedures?: In the alternative to Australia Act requiring a special manner to repeal legislation. Do these manner and form requirements/restrictive procedures compromise parliamentary sovereignty? Two views 1. Parliamentary sovereignty is logically based on a prior (common law? Or sui generis?) rule – the enactments of the Queen in Parliament are to be followed. Focus here is on what/who 33 constitutes Parliament. An argument then that Parliament can alter this prior rule and still remain sovereign. 2. Winterton: ‘At the most fundamental level, the question must be decided whether the authority to enact restrictive procedures is inherent in the traditional Westminster notion of parliamentary sovereignty or whether it is excluded by it.’ FEDERALISM IN THE CONSTITUTION Section 106: Subject to this Constitution, the Constitution of each State shall continue as at the establishment of the Commonwealth. Section 107: Every power of the Parliament of a colony which has become or becomes a State shall, unless It is by this Constitution exclusively vested in the Parliament of the Commonwealth or withdrawn from the Parliament of the State, continue as at the establishment of the States, as the case may be. INCONSISTENCY BETWEE N STATE AND FEDERAL LAWS Section 109: When a law of a State is inconsistent with a law of the Commonwealth, the latter shall prevail, and the former shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be invalid. Most powers granted under the Constitution to the Commonwealth are held concurrently by the States (e.g. s 51 powers), however the State is limited to the residual powers which do not conflict with the Commonwealth powers. Where a State law does conflict with a Commonwealth law, it wont apply to the extent of the inconsistency – if the federal law is later repealed, the State law will be fully operative again. The purpose of s 109 is to resolve conflicts between State and Federal laws – particularly where it becomes difficult for citizens to know which laws they are bound by if inconsistencies exist. It therefore serves a public institutional purpose, with one nation operating federally (Flaherty v Girgis (1989)). It also ensures that the Commonwealth government is protected against State laws impairing the functions of Commonwealth (Re Richardson Foreman & Sons Pty Ltd; Uther v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1947)). 34 TYPES OF INCONSISTENCY There are three types of inconsistencies that can arise between State and federal laws, which are consequently subject to s 109. IMPOSSIBILITY OF OBEDIENCE This form of inconsistency arises where citizens can’t possibly obey both. This therefore arises where there is a direct inconsistency between the legislation imposed by both. R v Licensing Court of Brisbane; Ex parte Daniell (1920) 28 CLR 23 State: Liquor Act 1912 (Qld) – s 166 stated that a State referendum on liquor hours will be held on the same day as the Senate election Commonwealth: Commonwealth Electoral (Wartime) Act 1917 (Cth) – s 14 stated ‘no referendum or vote of electors of any State or part of a State shall be taken under the law of a State on a Senate election day’ DENIAL OF RIGHTS This form of inconsistency arises where a law purports to confer a legal right, privilege, or entitlement that the other purports to take away. For example, this occurs where one law says you can do X, while the other law says that you can’t do X. This is similar to the above form of inconsistency; however, it differs on the basis that by one law saying you can do x, it is essentially possible to obey both at the same time – this is because the law allowing the right permits you to do it, rather than saying you must do it. Therefore, if you were to follow the law which states that you can’t do something, you are not in fact disobeying the other law. In order to determine whether a denial of rights occurs, it is therefore necessary to look at the practica l working and actual effects of each law. Example: where a Commonwealth law permits employing women in factories, and a State law makes it an offence – technically the laws can be applied simultaneously. However, this would amount to a contradiction of legal permission (Colvin v Bradley Bros Pty Ltd). 35 COVERING THE FIELD This form of inconsistency arises where the Commonwealth evinces an intention to ‘cover the field’ and State law also effectively operates in the same field. For this to arise, it necessarily requires legislative intention by the Commonwealth law that it will be the only law in that field. It is therefore necessary to consider: (see e.g., Victoria v Commonwealth (The Kakariki) (1937) 58 CLR 618, 630 (Dixon J)) 1. What field or subject matter does the Commonwealth law regulate, control, or deal with? 2. Does the Commonwealth law intended, expressly or impliedly, to cover that field completely and exhaustively? 3. Does the State law attempt to enter into or regulate the field or part of the field covered by the Commonwealth law? Essentially, the laws may be capable of being observed simultaneously, however inconsistency doesn’t lie in the mere coexistence of two laws that can do so. It depends on the intention of paramount legislature. The question is therefore: did the Commonwealth parliament want to completely, exhaustively and exclusively be the law on a particular matter? (Ex parte McLean (1930) 43 CLR 472, 483 (Dixon J)). INTERPRETATION OF INCONSISTENCY REQUIREMENT OF SIGNIFICANT CONFLICT In order to determine whether a State law conflicts with Federal law, particularly in instances where it is not a direct conflict (i.e. impossibility of obedience cases), it has been determined that a ‘real’ conflict will arise where alteration, impairment or detraction from the Commonwealth law is significant and not trivial (Jemena Asset Management (3) Pty Ltd v Coinvest Ltd (2011)). The notions of alternation, impairment, or detraction have in common the idea that State law conflicts with Commonwealth if the State law undermines the Commonwealth law. MAY LEAD TO A CONCLUSION OF NO CONFLICT In some instances, two or more interpretations of the law will be possible, and one or more of these interpretations will lead to the conclusion of no conflict. Where an interpretation of no conflict is possible, the Court has demonstrated in intention to read the legislation in a way that amounts to the conclusion of no conflict. Commercial Radio Coffs Harbour v Fuller (1986) 161 CLR 47 Facts: - Commonwealth licence for a news broadcasting station was given 36 - Condition of the licence was the construction of an antennae NSW environmental legislation amounted to a challenge on the basis of conflict Issue: whether the two laws were inconsistent and therefore State was invalid pursuant to s 109. Held: no inconsistency. Reasoning: - - The Commonwealth requirement was open to two interpretations, the effects of which were: 1. It authorised the breaching of NSW law 2. The duty did not extend to overriding the NSW law As the second interpretation was open, there was no intention to control the entire field Ansett Transport Industries (Operations) Pty Ltd v Wardley (1980) 142 CLR 237 Facts: - Equal Opportunity Act 1977 (Vic) prohibited sex discrimination in employment or dismissal Airline Pilots Agreement 1978 (Cth industrial award) authorised employers to employ and dismiss pilots Ansett refused to employ Wardley because of her sex Issue: Did the 1978 Agreement cover the field of dismissal to provide (as against the SA Act) an unqualified right to dismiss? Held: No inconsistency Reasoning: - - Stephen J: o SA Discrimination Act – a general law operating in all field o 1978 Agreement – a law detailing industrial matters – not ‘trespassing upon alien areas remote from its purpose and subject matter’ o The ‘unexceptional wording’ of the Agreement contained nothing to suggest it should ‘stand inviolate, unresponsive to the general law applicable to the community’ Mason J: o The Agreement did not evidence an intention to cover the field o The Agreement did not confer an absolute right; it was not a general industry award ‘which seeks to determine exhaustively the respective rights of employer and employee’ (Contrast Australian Broadcasting Commission v Industrial Court (SA) (1977) 138 CLR 399) INFERRING INTENTION TO COVER THE FIELD O’Sullivan v Noarlunga Meat Ltd (1954) 92 CLR 565 Facts: - The Metropolitan and Export Abattoirs Act 1936 (SA) s 52A – State license was required for slaughter in certain areas offence to breach 37 - The Commerce (Meat Export) Regulations (Cth) – prohibited export of meat unless slaughter was carried out in premises registered under Cth regulations Noarlunga – had Commonwealth registration but not State licence Issue: Whether the Commonwealth intended to cover the field. Held: Yes Reasoning: - - The comprehensiveness of Commonwealth regulations demonstrated an intention to cover the field of premises used for slaughtering Fullager J: o Elaborate and detailed scheme under the rgulations o State would be prohibiting the use of the premises for the purpose they had been registered with the Commonwealth to do o Registration set out authorised use, including slaughter Three judges considered registration udner Commonwealth regulation concerned grant of an export permit, not regulating slaughter of stock therefore covering different fields Consider the impact on federalism. Stock Motor Ploughs Ltd v Forsythe (1932) 48 CLR 128, 145 (Evatt J): - - Noted the movement away from impossibility of obedience broader covering the field concern despite possibility of simultaneous obedience On ‘covering the field’ ‘it is no more than a cliché saying that by reason of subject matter/method of dealing/nature and multiplicity of regulations prescribed means federal have adopted a plan which hinders additional regulations’ Said it is difficult to conceive of the Commonwealth law as completely covering the field for a number of s 51 matters e.g. State law imposing separate duties on aliens of State law imposing taxation MANUFACTURING INCONSISTENCY In some instances, the Commonwealth will manufacture inconsistency in an attempt to render State laws invalid. ISSUE: DECLARATIONS WITHIN LEGISLATION PURPORTING THAT COMMONWEALTH INTENDS TO COVER THE FIELD Is it valid? Is it an attempt to enlarge power? Is it against the general proposition that Commonwealth can’t enlarge its own power by trying to define them broadly beyond constitutional scope? The Commonwealth cannot deny validity to a State law by direct force, however the Commonwealth may expressly evidence intention to cover the field so that so 109 applies. In Western Australia v Commonwealth (Native Title Case) (1995) 183 CLR 373, 466: ‘the intention may appear from the text or from the operation of the law. The text may reveal the intention either by implication or by express declaration. And if it be within the legislative power of the Commonwealth to declare that the regime 38 prescribed by the Commonwealth law shall be exclusive and exhaustive, it is equally within the legislative power of the Commonwealth to prescribe that an area be left for regulation by State law’. ISSUE: IS THIS DIFFERENT FROM STATING AN INTENTION TO COVER THE FIELD? Example: in WorkChoices – s 16 of the Workplaces Relations Act 1996 (Cth) excluded State and Territory law that did not apply to anti-discrimination legislation Example: Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) s 6A(1): ‘This Act is not intended…to exclude or limit operation of a law of a State or Territory that furthers the objects of the ICCPR and is capable of operation concurrently with this Act. COMMONWEALTH V ACT (S AME-SEX MARRIAGE CASE) (2013) 250 CLR 441 Facts: - - - ACT passes the Marriage Equality (Same Sex) Act 2013 (ACT) o Defines marriage under the Act as: ▪ The union of 2 people of the same sex to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life; but ▪ Does not include a marriage within the meaning of the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) Commonwealth challenges the Act as inconsistent with the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) and the Family Act 1975 (Cth) o These define marriage as ‘the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life’ (Marriage Act 1961, s 5(1)) Challenge based on s 28 of the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988 (Cth). o Territory enactment has no effect to the extent it is inconsistent with Cth law. But ‘such a provision shall be taken to be consistent with such a [Cth] law to the extent it is capable of operating concurrently with that law.’ ACT argument - - ACT law could operate concurrently. Federal law provided for marriage as between persons of opposite sex. The ACT law provided for marriage between persons of the same sex. I.e. used marriage equality argument: different components of marriage. Court’s conclusion on concurrent operation ‘if a Commonwealth law is a complete statement of the law governing a particular relation or thing, a Territory law which seeks to govern some aspect of that relation or thing cannot operate concurrently with the federal law to any extent.’ [52] There can be no concurrent operation where (as with s 109 of the Constitution), the Cth evinces an intention to cover the field. 39 Legal Issues 1. Does s 51(xxi) – the power to make laws with respect to ‘marriage’ – give the Cth Parliament power to make laws respecting same-sex marriage? 2. Had Parliament evidenced an intention to cover the field of ‘marriage’ to the exclusion of state and territory legislation? Issue One: Is the Commonwealth empowered to make same-sex marriage laws? - - Yes. All parties submitted that ‘federal parliament has legislative power to provide for marriage between persons of the same sex. That submission is right and should be accepted’ [2]. Not necessary to consider this issue further. Should the court have addressed this? o Reasons for: If P didn’t have power, then ACT had a stronger argument [9]; if Cth did have power but didn’t use it, that raises cover the field issues. o Reasons against: our question is whether Cth intended law to be only law on marriage. No need to determine full scope of power as Marriage Act clearly within power. A sub issue: What is ‘marriage’? - - Whatever Parliament states? Problems… Fixed meaning? Should meaning at federation (union b/w man and woman to the exclusion of others for life) govern? Problems… The original or traditional understanding? Problems… o The ‘monogamous marriage of Christianity’/in Christendom may be the central case, but does not define the constitutional power [20] E.g. divorce [17]. o HC critical of any definition that carries a ‘preconceived notion of o what marriage “should” be’ [36]. o But if not tradition or sense of what it should be, then what? o ‘Debates cast in terms like "originalism" or "original intent" (evidently intended to stand in opposition to "contemporary meaning") with their echoes of very different debates in other jurisdictions are not to the point and serve only to obscure much more than they illuminate.’ [14] What the international community states? What succeeding generations of Australians determine? Another sub issue: How does the court reconcile that the definition is not entirely malleable or entirely fixed? - Marriage is a status power [21] (recall corporations in work choices) or ‘topic of juristic classification’ [14]. Recall ‘alien’ in Singh. Connotative meaning of marriage: o ‘a consensual union formed between natural persons in accordance with legally prescribed requirements which is not only a union the law recognises as intended to endure and be terminable only in accordance with law but also a union to which the law accords a status affecting and defining mutual rights and obligations.’ [33] 40 o Consider what is present and not present. Issue Two: Had Parliament evidenced an intention to cover the field of ‘marriage’? Why is this an issue? - An issue because can’t operate concurrently in the event of inconsistency. o ‘There cannot be concurrent operation of the federal and Territory laws if, on its true construction, the Marriage Act is to be read as providing that the only form of marriage permitted shall be a marriage formed or recognised in accordance with that Act.’ [56] Making the decision - - - Considered purpose of marriage power: ‘to enable the federal Parliament to provide uniform laws governing marriage and divorce’ [7]. Avoiding conflict of laws problem in a federal state. Considered indicators of intention to cover the field: o Marriage Act defines marriage; a ‘complete statement of the law’ [52]; ‘comprehensive and exhaustive statement’ [57]. Pointed especially to marriage definition and 2004 amendments. Is it relevant that the Commonwealth had not permitted SSM? o ‘The federal Parliament has not made a law permitting same sex marriage. But the absence of a provision permitting same sex marriage does not mean that the Territory legislature may make such a provision.’ [56]. TEST TO BE APPLIED IN EXAM 1. Ascertain the operation of Federal law. 2. Ascertain the operation of State law. 3. Determine whether State law, as interpreted, would impair or distract form the operation of federal law. 4. Make a judgment as to constitutional validity – s 109. a. Take into account the intention of federal parliament re: covering the field See e.g., APLA v Legal Services Commissioner (NSW) (2005) 224 CLR 322, 452 (Kirby J). 41 FEDERALISM: FINANCIAL RELATIONS, EQUAL T REATMENT AND INTERSTATE TRADE FEDERALISM Federalism is the ‘method of dividing power so that the general and regional governments are each, within a sphere, co-ordinated and independent…the essential point [is that]…neither general nor regional government is subordinate to the other’ (KC Wheare, Federal Government (Oxford University Press, 4th ed, 1963). Federalism effectively allows for the distribution of powers to the arms of government which are best suited to dealing with those powers – i.e. judiciary have the power to judge etc – whilst also ensuring a method of dialogue between the arms of government – i.e. making them accountable to eachother legislature’s legislation will be subject to judicial interpretation. ARGUMENTS IN FAVOUR OF FEDERALISM 1. Weakens the government: a. Through distribution of power there is no unitary sovereign b. Speed of government is limited – helping to ensure due process of law c. Harold Laski: ‘The necessity of balancing interests, the need for combing options, results in a wealth of political thought such as no state where the real authority is single can attain’ 2. Representation of coexisting societies 3. Enhancing representative politics a. Dual representation for citizens b. Easier participation at local levels c. Different structures offer more space for opinion, more resources to draw from precipitates more measured and scrutinised law 4. Voice and existence a. Individuals can participate more directly than in a monolithic unitary State b. Can also have the option to move to another State 5. Localising industry and policy 6. Fostering Competition a. Incentive to increase efficiency (Twomey and Wither argue that deferral states have proportionately fewer public services and lower public spending b. Incentive for creativity c. Where do you want your education? d. Diversity and innovation of industrial relations (Kirby WorkChoices 534) e. Innovations developed and adopted through States e.g. in electoral laws, human rights legislation 42 ARGUMENTS AGAINST FEDERALISM 1. National authority and local tyranny a. It may be needed to secure the rights of minorities in particular localities – for example, when QLD attempted to eliminate native title claims this gave rise to Mabo (No 1) which held that the attempt was invalid by applying the RDA 2. Duplication multiple levels of policies and taxes which could probably be more effectively applied as a Commonwealth scheme 3. Indeterminate jurisdiction national sovereignty may be simpler 4. Globalisation a need for and the rise of economic/political nationalism 5. Costly multiple bureaucracies 6. Subsidiary is sufficient CHARACTERISTICS OF AUSTRALIAN FEDERALISM Division of Powers: The Constitution expressly divides authority between the Federal and State governments, with the former confined to express enumerated powers listed under the s 51 heads of power while the latter is left with the undefined residue of Commonwealth power. We then have a judicial authority, namely the High Court, appointed by the Federal Government, which determines whether either level of government has exceeded its legislative, executive or judicial powers allowing for accountability. We also have a clear supremacy of federal laws over State laws, as determined by s 109, in the event of inconsistent legislation. Because our federal system is entrenched in a rigid constitutional framework it is difficult to amend. FEDERAL V NATIONAL CHARACTER OF THE CONSTITUTION The federal structure and composition of our Constitution can be found in ss 7 (equal representation within Senate), 106 and 107 (maintenance of powers not given to the Commonwealth, and the continuance of their constitutions), and 128 (role in amendment). Scholars, in particular Quick and Garran, also refer to the structure of the Constitution, as well as the structure of society in general, to depict the federal character of Australia. However, the Constitution also contains provisions which allude to a national structure of constitution. This is evident in ss 109 (supremacy of federal law), 117 (preventing of discrimination against residents of other States) and 92 (freedom of interstate trade and commerce) (refer below for discussions on 43 this). Stephen Gageler also opines that the function of federation was actually to create a nation of Australia rather than to enforce the separation of States. EQUAL TREATMENT PROVISIONS Provisions of the Constitution, particularly under those relating to equal treatment of States, point to a national construction of the Constitution in preference to a federal structure. Specifically, under ss 51(ii), 92, 99 and 117, the Commonwealth is given powers which are prohibited from discriminating between the States – reflecting the aspiration that Australia be a national State as opposed to federal. Relevant provisions: Section 51(ii): The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: … taxation, but so as not to discriminate between States or parts of States. Section 92: Trade within the Commonwealth to be free On the imposition of uniform duties of customs, trade, commerce, and intercourse among the States, whether by means of internal carriage or ocean navigation, shall be absolutely free. Section 99: Commonwealth not to give preference The Commonwealth shall not, by any law or regulation of trade, commerce, or revenue, give preference to one State or any part thereof over another State or any part thereof. Section 117: Rights of residents in States A subject of the Queen, resident in any State, shall not be subject in any other State to any disability or discrimination which would not be equally applicable to him if he were a subject of the Queen resident in such other State. The question in relation to equal treatment of States is: whether legislation with respect to a power which is limited by prohibitions on discrimination between States is ultimately invalid on the basis of discriminatory effect. This will be examined in relation to the application of the above provisions. UNDER THE TAXATION POWER 44 Typically, discrimination is prohibited on the grounds of both direct (discriminatory in form) and indirect (discriminatory in effect) discrimination. Further, where indirect discrimination occurs, the legislation will be balanced against the purpose to which it enforces discrimination in order to justify enacting the discrimination. However, in relation to taxation law, it has been determined that where legislation is discriminatory in in its terms it will be invalid, however not where it is discriminatory in effect. Differential taxes imposed on States will be deemed discriminatory, and therefore invalid. Cameron v Deputy Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1923) 32 CLR 68 Held: a law imposing a tax on the mining of gold at the rate of 20% in Western Australia and 30% in Tasmania was invalid on the grounds of discrimination. However, taxation applying equally to the States but with a differential impact is nondiscriminatory. Fortescue Mining Groups Ltd v Commonwealth (2013) 300 ALR 26 Facts: - Minerals Resource Rent Tax (MRRT): was levied at 22.5% of a miner’s annual profit over a prescribed threshold, less any royalties paid to the Commonwealth, State and Territories Varied royalties charged by different States meant the tax created different liability for people depending on State of residence Issue: Was this discriminatory? Held: No. Reasoning: - Hayne, Bell and Keane JJ (majority) o Rejected the notion that legislators must justify a differential impact looked at the purpose of s 51(ii) – prohibits discrimination between States or ports of States on the basis of geography or locality therefore discrimination only arises from the ‘application of different rules according to locality’ o Essentially determined that a miner in different States would not be exposed to differential effect if he were to conduct identical operation in each States – the mere fact that some States perform more mining activities was the sole reason for the discriminatory effect. o ‘In particular, a law is not shown to discriminate between States by demonstrating only that it will have a differential practical operation in different States because those States have created different circumstances to which the Act will apply.’ o The majority decision was reflective of the decision in Colonial Sugar Refining Company v Irving which determined that a tax applied at the same rate across States however having a greater impact on some as opposed to other would not infringe on s 51(ii). UNDER THE TRADE AND COMMERCE POWERS 45 Under s 99, relating to the trade and commerce power, two questions arise in interpreting the provision: 1. What is meant by ‘give preference’? Pursuant to s 99 (as above), the Commonwealth cannot give preference to one State over another. Elliot v Commonwealth (1936) 54 CLR 657 Facts: - Commonwealth regulations provided that at certain prescribed ports, a seaman could only be taken on with a licence This was limited to ports in some States Issue: Is differential treatment enough to breach s 99? Held: No Reasoning: - Latham CJ: the legislation must ‘amount to a trading or commercial preference’ for the legislation to be deemed discriminatory There must be a priority of treatment given to a State or part of a State a State must be ‘put before another or others’ In this instance, the preference could be construed as going to the seamen themselves rather than preference towards a State 2. How should the Court interpret the term ‘absolutely free’? Under s 92 (as above), the Commonwealth must ensure that legislation does not restrict the requirement that trade and intercourse among States be ‘absolutely free’. Questions arise, however, in relation to what it is they are to be free from. Does it provide for an individual right to be free from restraints in trading i.e. against national monopolies? This question represented a shift from the requirement that all State intercourse be completely free from restriction, towards the notion that a limitation be reasonably required to achieve objects of legislation. Consequently, the basic interpretation of ‘absolutely free’ is that the Commonwealth may restrict trade only where it is a reasonably required means to achieve an end (Cole v Whitfield). AMS v AIF (1999) CLR 160 Dicta provided by Court: WA Court had to consider whether impediment of preventing movement is ‘greater than reasonably required to achieve the objects of the applicable legislation’ This will be further discussed and analysed in the Freedom of Interstate Trade section below. 46 UNDER THE RIGHTS OF RESIDENTS IN STATES Under s 117 (as above), citizens shall not be subject to any unjustified disability or discrimination in one State as opposed to another State. Street v Queensland Bar Association (1989) 168 CLR 461 Facts: - - Rules of the Supreme Court (Qld) required an applicant to state that: ‘it is my intention to practice principally in the State of Queensland commencing on (here set forth any relevant date).’ New rule also imposed a one-year period of conditional admission on out-of-State applicants, during which the applicant had to show that ‘he had practiced principally in Queensland’. Issue: Did this qualify as discrimination against an out of State resident? i.e. Would the legislation have not been ‘equally applicable to him if he were a subject of the Queen resident in Queensland?’ Held: Restrictions invalid on the grounds of unjustified discrimination Reasoning: - - - The Court must look to the real effect of the legislation – therefore, needs to ask: would the ‘national fact of residence within the legislating State…effectively remove the disability or discrimination or significant deprive it of its onerous nature?’ Mason CJ: The very object of federation was to bring into existence one nation and one people’ the section is designed to ‘enhance national unity and a real sense of national identity’ Deane J: It is important that necessary restrictions flow naturally from the practice of medicine or law and the obvious need to protect the public from unqualified and incompetent practitioners however that was not the case here Significant considerations: Discrimination can be justified in certain circumstances, for example: - - - Brennan and Deane JJ: where it is necessary to preserve institutions of government and the ability to function e.g. only in-State residents can vote for their State senator this preserves the Constitution itself Mason CJ: where they don’t ‘detract from the concept of Australian nationhood or national unity which is the object of the section’ i.e. where State welfare benefits differentially treat people depending on State of residence but appropriate to State autonomy Dawson J: the purpose of the legislation must be capable of being seen as other than to impose a disability upon the residents of other States or to subject them to discrimination Gaudron J: ask whether different treatment is reasonably capable of being seen as appropriate. Are the means reasonably relevant to achieving the end? 47 FREEDOM OF INTERSTATE TRADE – S 92 Consideration of s 92 considers the second question relating to equal treatment under the trade and commerce powers, namely: how should the Court interpret the term ‘absolutely free’ pursuant to s 92 (as above)? Pre-Cole v Whitfield the Court interpreted s 92 with an individual rights approach: Bank of NSW v Cth (Bank Nationalisation Case) (1948) The majority held that the ‘object of s 92 is to enable individuals to conduct their commercial dealings and their personal intercourse with one another independently of State boundaries – analogous of religious freedom in s 116, or of equal rights of all residents in all States in s 117.’ This was rejected on appeal – agreed on the individual rights approach but not that the freedom was ‘absolute’. The result of the Bank Nationalisation Case was that the two qualifications created increasing uncertainty for the Court about the types of regulations or controls that would be in breach of s 92. Cole v Whitfield (1988) 165 CLR 360 Facts: - Tasmanian Sea Fisheries Regulations imposed a size restriction on crayfish sold in Tasmania The SA regulations relating to size restrictions on crayfish was smaller than the restrictions on Tasmanian crayfish Respondent charged with possession of undersize crayfish contrary to the Tasmania regulations They brought in crayfish from SA and intended to sell them at markets on the mainland and overseas – they were also of a size greater than the prescribed minimum size in SA Issue: whether the Tasmanian restrictions were invalid on the grounds of discrimination pursuant to s 92. Held: S 92 had not been infringed Reasoning: - - The regulations were discriminatory in effect, however the purpose was to protect sustainability of crayfish farms and it did not go beyond prescribing a reasonable standard Court looked to meaning of s 92 through the Convention Debates (original understanding) to identify the ‘contemporary meaning of the language used, the subject to which that language was directed and the nature and objectives of the movement towards federation from which the compact of the Constitution finally emerged.’ determined that s 92 intended to create free trade throughout the Commonwealth, to deny the Commonwealth and States a power to ‘prevent or obstruct the free movement of people, goods and communication across State boundaries’ Intention of the Framers went beyond the natural words of the provision – the expression of ‘free trade’ commonly signified an absence of protectionism 48 - Held that interstate trade and commerce is to be ‘immune only from discriminatory burdens of a protectionist kind’ supported by s 51(i) Result of Cole v Whitfield: s 92 prohibits imposition of discriminatory burdens on interstate trade and commerce of a protectionist kind i.e. subjection of interstate trade and commerce to disabilities or disadvantages for purposes of protecting intrastate trade and commerce from external competition. Test for determined by Cole v Whitfield: 1. Burden: does the legislation burden the freedom of interstate trade? 2. If yes, does the burden subject interstate trade or commerce to a disadvantage or disability, or produce a disadvantage or disability in its effect? - This means for States: the legislation discriminates in favour of intrastate trade such as where these is a discriminatory purpose or effect. - This is less likely to arise where the law is of general application/applies to everyone – however this does not dismiss the ability for the legislation to be discriminatory in effect 3. If yes, does the discriminatory burden have a protectionist purpose or effect - This is a matter of fact and degree for judicial assessment (Cole) - Distinguish between regulation ‘necessary for the conduct of business’ or prescribing ‘a standard for a product or a service’ - Does it give intrastate and commerce a competitive market or market advantage over interstate trade and commerce - If yes: prima facie invalid 4. If the protectionist effect pursuant to, or incidental to, some non-protectionist purpose? - If yes: does not breach s 92 Castlemaine Tooheys Ltd v South Australia (1990) 169 CLR 436 Facts: - SA requires corporations who use bottles to offer a specific refund amount to consumers who return bottles SA passed a law to make it disadvantageous to use non-refillable bottles when selling beer – higher refund required (15c v 4c) Non-refillable bottle refund applied to any retailer; refillable bottle refund limited to depots Disproportionately affects Bond Brewing, an out of State brewer attempted to gain market share in SA, who used non-refillable bottles Measure was passed specifically with this in mind (BB would make gains) but was framed around environmental concerns Issues: 1. Was the legislating in contravention of s 92 despite underlying social purpose? 2. How should the court approach the determination of the validity of State legislation which attempts on its face to solve pressing social problems by imposing a solution which disadvantages intrastate trade in a market? 49 Held: 1. Yes, it was invalid 2. The social purpose of the legislation must be reasonably and appropriately adopted Reasoning: - - The amount of the refund (15c) indicated the object was to disadvantage the sale of beer in non-refillable bottles, however the level did not need to be so high to provide a means to the end HC noted that there were alternatives available that would impose less of a burden The price of refund needed only be 6c to encourage environmental protection Disproportionate and therefore protectionist Necessary to take into account the fundamental power of a state legislature to legislate for the wellbeing of the people of the State Interstate trade must submit to a burden that is ‘necessary or appropriate and adapted to the protection of the people of the State from a real danger or threat to its well-being’ Betfair Pty Ltd v WA (2008) 234 CLR 418 (‘Betfair No 1’) Facts: - Betfair is an internet betting exchange Gamblers can bet against each other using the site Betfair received a commission on winnings Would take revenue away from the States, which had arrangements with TABs WA passed legislation prohibiting betting exchanges and prohibiting publishing information on a WA race anywhere without prior approval Approval had to be sought from a Minister who committed to eliminating betting exchanges WA had a statutory body operating the TAB agencies and fixing betting rates – would control all race information WA’s claims: 1. Betting exchanges do not contribute financially to the racing industry 2. Allows punters to back a contestant to lose – threatens the integrity of the industry 3. Operation entails a loss of revenue to the State Held: Court rejected all three claims and found it to be protectionist and therefore invalid Reasoning: - ‘You need an acceptable explanation or justification for the differential treatment’ The State’s purpose was more in line with preventing competition Criticisms of Castlemaine: - Emphasis on well-being of the people in Castlemaine does not account for the ‘new economy’ – focus shifted from the people of the State to the demand and supply side of commerce Court is now focusing on national economy because ‘the inhibition of competition presented by geographic separation between rival suppliers and between suppliers and customer is reduced by the omnipresence of the internet and the ease of its use’ 50 Comparison of the three cases above: Cole – permits regulatory action wih discriminatory effect when it’s necessary for standard; restricted reach of s 92 by looking to economic thought of 19 th Century conventions Castlemaine – permits regulatory actions, with discriminatory effect, for protecting state’s people where the impact on interstate trade is not disproportionate to the objective (i.e. environmental concern) Betfair No 1 – looks to whether comparable supplier has suffered competitive disadvantage disproportionate to a competitively neutral objective (protecting racing industry); expanded reach by looking to economic ideology/context of the 21st Century Betfair v Racing NSW (2012) 286 ALR 221 (‘Betfair No 2’) Facts: - Betfair operated out of Tasmania Objected to fees imposed by statutory authorities in NSW Fees on ‘wagering turnover’ were facially neutral Betfair argued that it was commercially disadvantaged because of its different business model - the fee absorbed a higher proportion of its turnover In effect: the law affected Betfair’s revenue structure, however did not necessarily effect its market share Issue: whether the effect of the legislation was contrary to s 92 Held: No Kiefel J (dicta): it might be necessary to ‘go beyond what was decided in Cole (i.e. beyond the protectionist requirement) to recognise that any effect of lessening competition in a market which operates without reference to State boundaries is contrary to s 92.’ Themes and issues discussed in relation to s 92: 1. Interpretation a. Textualist understanding of absolutely free pointing to individual rights theory in which individual and interstate traders to be protected from any burdens b. Originalist understanding altered it to more predominately concerned with the effect on trade itself 2. Nationalist concerns: a. Individual rights b. Shit to protectionism 3. State power – when can state disadvantage interstate trade to promote wellbeing of citizens a. Castlemaine – emphasis on proportionality b. Scepticism in Betfair – emphasis on reasonably necessary TEST TO BE APPLIED I N EXAM 51 TEST ONE: 1. Does the legislation impose unequal restrictions or responsibilities on States? (i.e. is it clearly discriminatory in form?) a. If yes, and it relates to the application of taxes contrary to s 51(ii) (Cameron v Deputy Commission of Taxation) b. If yes, and relates to the rights of citizens across State borders contrary to s 117 (Street v Queensland Bar Association) c. If yes, and in relation to ‘giving preference’ to a State in Trade or Commerce contrary to s 99 (Elliot v Commonwealth) 2. If no, does the legislation impose a burden which is discriminatory in effect? a. If yes, and relates to taxation valid so long as it is non-discriminatory in purpose (Fortescue Mining) b. If yes, and relates trade and commerce, refer to TEST TWO TEST TWO: (also refer to test established under Cole v Whitfield) 1. Is interstate trade subjected to the burden of a competitive disadvantage or disability? 2. Is the burden discriminatory in either purpose or effect? (Cole v Whitfield) 3. Is the discrimination on protectionist grounds? (Cole v Whitfield) a. If yes, will be invalid 4. Alternatively, is the protectionist ground incidental to a legitimate competitively neutral objective? a. Is it necessary and appropriately adapted? (Castlemaine) b. Is it reasonably necessary? (Betfair No 1) c. Consider the future direction beyond protectionism as under Kiefel J’s dicta in Betfair No 2 52 EXECUTIVE POWER Section 61: The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the Queen and is exercisable by the GovernorGeneral as the Queen’s representative, and extends to the execution and maintenance of this Constitution, and the laws of the Commonwealth. Section 61 is silent as to the scope of the power. According to Winterton, there are seven sets of power: 1. Power conferred on executive by statute. Limits to these powers and means of holding the executive to account – administrative law 2. Powers although not conferred directly by a statute are necessary or incidental to the execution and maintenance of a law of the Commonwealth. I.e. when Cth passes laws, Executive may be granted power to undertake actions to that legislation’s implementation. 3. Powers necessary or incidental to the administration of a department of State established under s 64 of the Constitution- ‘The Governor-General may appoint officers to administer such departments of State of the Commonwealth as the Governor-General in Council may establish’ 4. Powers defined by the capacities of the Commonwealth common to legal persons. See Williams No 1 – Cth argued it could make contracts. 5. Powers expressly conferred by the Constitution. 6. *The prerogative powers of the Crown properly attributable to the Commonwealth. 7. *Inherent authority derived from the character and status of the Commonwealth as the national government. PREROGATIVE POWER The prerogative power is a form of primary legislation that the executive can undertake. Traditional examples include: 1. Sovereign has the power to declare was (prerogative of war) 2. Sovereign power to dispense with punishment for any criminal e.g. if terminally ill (prerogative of mercy) This is seen as incorporated in s 61 but they pre-exist the provision. Essentially, the powers were passed down to us upon federation by the Commonwealth. Ruddock v Vadarlis (Tampa Case) (2001) 183 ALR 1 Issue: was there a prerogative power to expel aliens or was this power now overtaken by the Migration Act? 53 French J: There was a prerogative power to expel aliens conferred by section 61. The Migration Act doesn’t evidence intention to take this power away. - Section 61 is the source of executive power, not the prerogative. This is because s 61 is ‘a power conferred as part of a negotiated federal compact expressed in a written Constitution distributing powers between the three arms of government’ (49). However, s 61 may gain some of its content from the prerogative. Section 61 is subject to the limitations imposed by the Constitution and laws passed under it. On the power to exclude, using s 61: ‘The power to determine who may come into Australia is so central to its sovereignty that it is not to be supposed that the government of the nation would lack under the power conferred upon it directly by the Constitution, the ability to prevent people not part of the Australia community, from entering …’ 52 Black CJ, dissenting: s61 doesn’t provide this prerogative power to expel, but in any event, the Act now provides a comprehensive scheme - - There are doubts whether the prerogative power to expel aliens (and in peace time) still exists. Raises a difficult issue: can a prerogative power be revived after it has fallen into disuse? Note: Prerogative powers are historical. UK Courts have, for example, stated that new prerogative powers will not be recognised. See BBC v Johns [1965] Ch 32, 79 per Diplock CJ. ‘It would be a very strange circumstance if the at best doubtful and historically long-unused power to exclude or expel should emerge in a strong modern form from s 61 of the Constitution by virtue of general conceptions of ‘the national interest’. (12) Parliament then passed retrospective legislation so the case not appealed. Scholarly interpretations of the power - Blackstone: Powers, rights, immunities, or privileges necessary to maintaining government, and not shared with private citizens (this definition would mean a definable list). Dicey: ‘a residue of discretionary or arbitrary authority’ … ‘Every act which the executive government can lawfully do without the authority of the Act of Parliament is done in virtue of this prerogative’. This was accepted in A-G v De Keyser’s Royal Hotel [1920] 2 AC 508 (HL). SCOPE OF S 61 Emphasis on Responsible Government: McHugh J discussing the Constitution Act 1855 (NSW) - - ‘Contemporary materials make it clear that the Imperial authorities intended that the new Constitution would be administered in accordance with the principles of responsible government.’ Parliament (as opposed to Executive) ‘provides the money required for administrative purposes by authorising taxation’ appropriating where money is to be provided and criticises mode in which money is spent and in which public affairs are administered. 54 - Support indispensable to those who are responsible for administration, but it does not administer. This task left to executive. Historical Context and Nationhood: - - - - In the past, prerogative power referred to as the ‘nationhood’ power – arising from the inherent right of the Commonwealth to protect itself; an implied right (e.g. sedition laws). But more recently the Court has shifted to grounding this in s 61, with an ancillary legislative power under s 51(xxxix). Section 51 (xxxix) enables Parliament to make laws with respect to ‘[m]atters incidental to the execution of any power vested by this Constitution … in the Government of the Commonwealth’ ‘While history and the common law inform [s 61’s] content, it is not a locked display cabinet in a constitutional museum. It is not limited to statutory powers and the prerogative. It has to be capable of serving the proper purposes of a national government.’ (Pape v Commissioner of Taxation (2009) 238 CLR 1, 60.) As well as appealing to prerogative, court has talked about nationhood power, or power vested in Executive for purpose of serving a national government. NATIONHOOD POWER Commonwealth v Tasmania (Tasmanian Dam Case) (1983) 158 CLR 1 Facts: - World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983 (Cth) allowed for protecting declared property on basis that it is part of Australia’s heritage and by reason of lack or inadequacy of other available means for protection, it’s appropriate to protect by national Parliament and Government. Relevance: The notion of nationhood under s 61 not considered, or denied as a proper use of the power because it arises most likely where there is no conflict with the states. Davis v Commonwealth (1988) 166 CLR 79 Facts: - Concerning bicentenary of settlement in NSW. Davis marketed Tshirts saying 200 years of suppression and depression. Bicentennial laws restricted use of logos and words. Held: legislation invalid because they lacked proportionality. Reasoning: - Mason CJ, Deane and Gaudron JJ: - ‘These responsibilities [are] derived from the distribution of legislative powers effected by the Constitution itself and from the character and status of the Commonwealth as a 55 - national polity’ (92)- that is why there is a national power- to take action for national purposes. - ‘the existence of Commonwealth executive power in areas beyond the express grants of legislative power will ordinarily be clearest where Commonwealth executive or legislative action involves no real competition with State executive or legislative competence.’ (94) Brennan J: - The Constitution did not create a mere aggregation of colonies, redistributing powers between the government of the Commonwealth and the governments of the States. The Constitution summoned the Australian nation into existence’ (110) - On that basis, we can recognise that Executive has a national power. - Initiatives that strengthen the nation and supported by s61: e.g. flag and anthem, national initiatives in science and literature. - ‘Where the Executive Government engages in activity in order to advance the nation – an essentially facultative function – the execution of executive power is not the occasion for a wide impairment of individual freedom’ … ‘In my opinion, the legislative power with respect to matters incidental to the execution of the executive power does not extend to the creation of offences except in so far as is necessary to protect the efficacy of the execution by the Executive Government of its powers and capacities …’ (112-3) i. Contrasting valid national initiatives e.g. flags/anthem with what was being done here, by establishing overly restrictive and coercive laws allowing Bicentennial authority to fine people for using flags/logos etc. Coercive laws appealing to the executive power Pape - ‘absent authority supplied by a statute under some [other] head of power … likely to be answered conservatively’. Australian Communist Party v Commonwealth (1951) 83 CLR 1 at 187 - - ‘History and not only ancient history, shows that in countries where democratic institutions have been unconstitutionally superseded, it has been done not seldom by those holding the executive power. Forms of government may need protection from dangers likely to arise from within the institutions to be protected.’ More reluctant to allowing coercive powers appealing to nationhood. APPROPRIATIONS AND SPENDING Section 81: All revenues or moneys raised or received by the Executive Government of the Commonwealth shall form one Consolidated Revenue Fund, to be appropriated for the purposes of the Commonwealth in the manner and subject to the charges and liabilities imposed by this Constitution.’ 56 Effects of an appropriation Act - Authorises the government to withdraw money from the Consolidated Treasury Fund; Directs purposes to which the money can be applied by the Executive government Issues arising under section 81 1. Does Section 81 provide authority to spend the money or must that authority be found elsewhere? - Pape: all judges agree that appropriation act doesn’t provide Executive with authority. - The consequence of this decision was that numerous expenditures thought justified by s 81 now in doubt. o E.g. Hayne and Kiefel JJ suggested that CSIRO might now be supported as an exercise of the patents power in s51(xviii). 2. Are there any limits on how the Executive can spend public money? What authorises Executive spending in the absence of specific legislation? In Williams v Commonwealth (2012) we see that the Commonwealth government argued that: - Inherent authority derived from the character and status of the Commonwealth as the national government; Powers necessary or incidental to the administration of a department of State established under s 64 of the Constitution; Powers defined by the capacities of the Commonwealth common to legal persons (thus without statutory authorisation, may contract like an ordinary person and this is at least coextensive with the scope of federal legislative power). This was rejected. NATIONHOOD AND CONTR AC TING The executive power (pursuant to s 61 as above), relates to ‘executing’ and ‘maintaining the Constitution and the law of the Commonwealth. The scope of this power is not mentioned in the Constitution, however the scope is examined in relation to two components: 1. Action peculiarly adapted to a national government (nationhood power in Pape) 2. Contractual capacity to spend (Williams) PAPE V COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION (2009) 238 CLR 1 57 Facts: - Challenged validity of the Tax Bonus for Working Australians Act (No 2) 2009 (Cth). Section 5 of the Act created an entitlement to a ‘tax bonus’ for certain categories of Australian tax payers. Appropriation supporting for payments found in Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth). Taking of money from consolidated fund. Mr Pape raises a challenge. Legal issues 1. Is an appropriation alone sufficient to authorise executive spending? 2. If not, was there a source of power to spend the appropriated funds, and a head of legislative power capable of supporting the Tax Bonus for Working Australians Act (No 2) 2009 (Cth)? Held: 1. Is an appropriation alone sufficient to authorise executive spending? o Unanimously: ss 81 and 83 (appropriations and drawing money) do not confer a substantive spending power o ‘The relevant power to expend public moneys, being limited by s 81 to expenditure for “the purposes of the Commonwealth”, must be found elsewhere in the Constitution or statutes made under it.’ [8] o Sections 81 and 83 are parliamentary controls of the exercise of executive power to expend public moneys they do not authorise executive spending. 2. If not, was there a source of power to spend the appropriated funds, and a head of legislative power capable of supporting the Tax Bonus for Working Australians Act (No 2) 2009 (Cth)? o Yes, S 51 (xxxix) gives incidental power to legislate and EP allows for scheme a. What underpinned the executive action (spending)? b. What supported the legislation? i. Section 51(xxxix) incidental power to legislate. ii. This enables Parliament to make laws with respect to matters incidental to the execution of any power vested by this Constitution…in the Government of the Commonwealth.’ iii. Thus, to activate and enliven this provision, we need to find a power vested in the Commonwealth government. iv. I.e. consider if impugned legislation was enlivened by S 61- Executive Power. Construction of the Executive Power: - Collection of statutory and prerogative powers (not exercised by states) and non-prerogative capacities. These form part of but do not complete the EP Power to ‘engage in enterprises and activities peculiarly adapted to the government of a nation and which cannot otherwise be carried on for the benefit of the nation’: Victoria v Commonwealth (1975) 134 CLR 338, 397 (AAP Case) Mason J 58 - - The Court denied existence of an implied nationhood power. Why? Due to concern that government could invoke implied nationhood power to overcome any division of powers between states o Typical example would be implied power to make laws against sedition (undermining the government) Instead of being implied, it is found within section 61 EP. Davis (1988) 166 CLR 79, 93-94 Mason CJ, Deane and Gaudron JJ: ‘the existence of Commonwealth executive power in areas beyond the express grants of legislative power will ordinarily be clearest where Commonwealth executive or legislative action involves no real competition with State executive or legislative competence.’ o I.e. unlikely to find that Cth can engage in nationhood power under EP if it would incur competition with states. Chief Justice French Believed that the Tax Bonus scheme was permissible. He focused on: - Short-term measures; speed and efficacy Economic conditions facing nation as a whole Peculiarly within capacity and resources of Commonwealth Not affecting distribution of powers Justices Gummow, Crennan and Bell Also believed that Tax Bonus scheme was permissible but for different reasons: - - - - Stated (90) that the EP ‘enables the undertaking of actions appropriate to the position of the Cth as a polity crated by the Constitution and having regard to the spheres of responsibility vested in it’ Gave a more expansive reading of the EP than French. They say that under an appeal to nationhood you can undertake power appropriate to the Commonwealth position. However French focuses on emergency and crisis. Nevertheless, their test of ‘undertaking actions’ was satisfied because Australia in GFC. They also emphasised historical significance [230]- worst crisis since Great Depression. Compared to national emergency. Said that Cth is the only body with resources capable of meeting the national emergency. However, would be inappropriate if it distributed state executives to undertake own regulation Justices Hayne and Kiefel (dissent) Did not support the Tax Bonus scheme. They criticise: - Subjectivity: As compared to prerogatives and capacities (specific), they asked how Courts could possibly assess which actions a national government is best placed to undertake. Aggrandising executive power: too broad. Critical of relying on notion of emergency [347]: this would justify any action if we are truly in an emergency. 59 - - Alternatives more appropriate: if the government wants to fuel the economy then give grants to states to build roads or use taxation power to reduce income tax or give tax rebates o Counter-argument evident in French’s reasoning: Appeal to speed and efficacy. Roads take too long and this would be an immediate injection into bank accounts Federalism: a power could be greater than the distribution of powers granted to the Commonwealth if it can declare emergencies or satisfy notions that the Cth is best placed to undertake an action. This is too expansive and subjective WILLIAMS V COMMONWEALTH (2012) 248 CLR 156 Facts: - - Williams challenged: o National School Chaplaincy Programme, and o Funding agreement (contract) between Cth and Scripture Union Qld (DHF agreement) Note that these were not authorized by statute o Thus the Cth was claiming to spend in the absence of legislation; taking money from consolidated fund arguing there is an EP to spend money for Cth to enter into contracts o Funding was appropriated under annual Appropriation Acts Commonwealth’s arguments Appealed to executive power …to spend. Made two arguments: 1. (Broad argument): Executive power to spend is unlimited because the Executive enjoys capacities similar to any ordinary person. The Crown is a juristic person and can enter into contracts (failed) 2. (Narrow argument): Cth can enter into contracts without legislation so long as subject matter of contract can be pinned to a head of power (failed) Narrow arguments by the Commonwealth: - - - EP is, in all matters, limited to subject matters of express grants of power in ss 51, 52 and 122 together with ‘nationhood’ component (those peculiarly adapted to the government of the nation). Executive power to spend (exercising a ‘capacity’) supported by: o Providing benefits to students (s 51xxiiiA) o Contracting with a constitutional corporation (s 51xx). Additional question: was it supported by the nationhood power (s 51xxxix) enlivened by section 61? I.e. Pape through contract. 60 Commonwealth ‘capacities’ - Refers to things the Commonwealth can do as a juristic person Traditionally understood as one branch of section 61’s content Juristic persons can contract, create trusts, transfer property, register companies etc. Thus argued it can establish royal inquiries and scientific bodies. The Cth argued that constraining contractual capacity would constrain other abilities as a juristic person. How the Judges divided - - - French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ: o Rejected the broad and narrow submissions o The Cth’s executive power to spend is not coextensive with the potential scope of its legislative power o The scheme could only be supported by legislation enacted by Parliament Hayne and Kiefel JJ: o Rejected the broad submission o Unnecessary to determine the correctness of the narrow submission o Clear that the NSCP could not be the subject of a valid law under s 51 Heydon J: o Unnecessary to determine the correctness of the broad submission o Accepted the narrower submission o Considered the NSCP was within executive power because it was supported by the legislative power under s 51(xxiiiA) Does the Commonwealth have contractual capacity to expend money? No - ‘The Cth is not just another legal person’ [38]. Personal contracts don’t have the effect or power like Cth contracts. The latter can affect exercise of power by State executives. They affect vertical distribution of power. (CJ French) See [31], [77]. Note that we must consider this but affecting states isn’t a criterion of invalidity o ‘Expenditure by the Executive Government of the Commonwealth, administered and controlled by the Commonwealth, in fields within the competence of the executive governments of the States has, and always has had, the potential, in a practical way of which the Court can take notice, to diminish the authority of the States in their fields of operation. That is not a criterion of invalidity. It is, however, a reason not to accept the broad contention that such activities can be undertaken at the discretion of the Executive, subject only to the requirement of appropriation.’ French CJ [37] o This seems a step back from Engineers because it’s saying we won’t read s 61 broadly because doing so would diminish capacity of states. Yet, note that French said it’s not a criteria for invalidity. If s 61 did permit spending money however it liked, then it would be permissible. But natural meaning of s 61 doesn’t lead us to that wider scope because of these concerns (encroaching on States) 61 - It assumes that Executive is spending its own money just as another person may do (Hayne) see [216] Was the executive power co-extensive with Commonwealth (hypothetical) legislative power? No Federalism concerns: ‘In tension with the federal conception’ [60] Summary (CJ French) [83] - - The Commonwealth claimed that its scheme was supported by heads of power (benefits to students; corporations) without statutory authorization Decision: you need authorisation for such a claim It did not fall within recognised parts of the Executive Power o Well recognised functions of government; grants by legislature; prerogative or national character component Raises an undecided question Was it necessary for a ‘national government’? This was relevant because in Pape under s 51(xxxix) legislation supported by action proper for a national government. The question thus in Williams was whether the scheme could be supported by legislation for action proper for a national government. Gummow and Bell JJ [46] - Unlike Pape, not a natural disaster or national economic or other emergency. The States have the legal and practical capacity to deal with the issue. Could use Section 96. Kiefel J [599] - The Executive was requiring national standards, which had real potential for conflict with State (QLD) standards. Thus unlikely to find it was necessary for national government. Hayne J (still part of majority but different reasons) - - Executive power to spend ‘must be understood as limited by reference to the extent of the legislative power of the Parliament’ [252]. Permitting otherwise would empower the Commonwealth (through s 51(xxxix)) to legislate for expenditure contrary to division of powers [248] He is accepting narrow submission of Cth but says here there is no power that would empower such spending. The reason for this is that benefit to students means ‘material benefit’ with ‘identifiable students’. Concurring opinion from Crennan J. o Issue: who decides what equals a benefit? Summary - Held: only a certain exempt class of Commonwealth contracts could be entered into without prior legislative authorization 62 o - - - - Contracts related or incidental to the ordinary, well-recognised functions of government e.g. those about internal workings of government department. See [43] French CJ. Otherwise you need authorisation by legislation appealing to a head of power (with some suggestion that exercise of nationhood power will not require additional legislative authorisation). We are seeing denial of juristic personality. o Republican character: The Executive as one branch of government; shift away from ‘the Crown’; emphasising different understanding to UK. We see a re emphasis on federalism. Including reserving state executive power against encroaching federal executive power. Nationhood power (part of section 61): o Power ‘to engage in enterprises and activities peculiarly adapted to the government of a nation and which cannot otherwise be carried on for the benefit of the nation’ Victoria v Commonwealth (1975) 134 CLR 338, 397 (AAP Case) Mason J. May support contracting/exercise of capacities. Still likely to require legislative authorisation: plurality opinion in Williams. Issues to consider - Federal and state executive competition. Distribution of power. Lingering Questions: Raised by CJ French: Is there an inherent power to spend, appealing to the nationhood power, without statutory authorisation under s 51 (xxxix)? 63 JUDICIAL POWER C HAPTER III JUDGES Appointment of Judges to the High Court High Court of Australia Act 1979 (Cth): - S 7: the appointee must be a judge of a federal or State court, or else have been enrolled as a legal practitioner for five years or more; S 6: the Attorney General shall consult with the State Attorney Generals – difficult to know if this has any real impact In practice the High Court judges get appointed on advice of the government. There are no required qualifications, other than those appointed relating to prior-practice, other than age. This is contrasted with the Federal Court, Family Court and the Federal Magistrates Court since 2007, which have explicit appointment criteria, advertisements for expressions of interest, and the use of advisory panels to develop a shortlist of suitable candidates. Representation in the judiciary has mostly been from NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, with no representatives from TAS or SA. TO date there have also been 47 men and 4 women (with another woman being nominated currently). Removal of Judges from the High Court Section 72 of the Constitution - Must retire by 70 Removed by GG in Council, on address from both Houses of Parliament in the same session ‘on the grounds of proved misbehaviour or incapacity’ Misbehaviour: - No definition Question: is it up to the Parliament to decide? Judicial Misbehaviour and Incapacity (Parliamentary Commissions) Act 2012 (Cth) – Commission of Inquiry may be constituted to investigate the factual basis for any potential actions; the action itself still remains with the Parliament 64 JURISDICTION OF THE HIGH COURT Original Jurisdiction The High Court has original jurisdiction (ss 77 and 76) over, specifically, the following matters: - Where the Commonwealth or a person on behalf of the Commonwealth is a party Between States, residents of States, or between States and a resident of another State In which a writ of Mandamus (requiring action) or prohibition or injunction sought a gainst officer of the Commonwealth Arising under the Constitution, or involving its interpretation – s 76, but conferred by Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) s 30(a) Appellate Jurisdiction The High Court also has appellate jurisdiction (s 73 Constitution) in: - Appeals from within HC itself (e.g. one judge sitting alone) Appeals from any federal court or court exercising federal jurisdiction Appeals from any State SC or any State courts from which it was formerly possible to appeal to PC Relevance of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth): appeals from any State court requires special leave of the High Court (s 35) ‘Matters’ Sections 73-77 give the HC jurisdiction in relation to the consideration of ‘matters’ – it cannot, however, give advisory opinions (see Momcilovic v The Queen). In In re Judiciary and Navigation Act (1921) determined ‘there can be no matter within the meaning of the sction unless there is some immediate right, duty or liability to be established by the determination of the Court’ (see also Kable – court was not required to make any determination with regards to rights and liabilities etc.). Judgments, decrees, orders, and sentences: - Appeals may be heard from ‘all judgments, decrees, orders and sentences’ – s 73 Cant take appeals to HC from exercise by State courts of any non-judicial function validly conferred on them by a State legislature (see second limb of Boilermakers). The separation of judicial power from the other branches of government was discussed in dicta Victorian Stevedoring & General Contracting Co Pty Ltd & Meakes v Dignan: - Two principles of separation were suggested by Dixon J (dicta): 1. Judicial power can only be vested in a Court as per Ch III of the Constitution (s 71) 2. A Court as per Ch III of the Constitution can only be invested with judicial power (cannot be invested with non-judicial power) 65 - This is except for those additional powers which were strictly incidental o its functioning as a Court Thus, judicial and non-judicial power cannot be mixed up in the same Court. WHAT IS JUDICIA L POWER According to case law, there is no single superior approach to questions of constitutional interpretation with regards to defining judicial power. Difficulty therefore arises in attempting to formulate a comprehensive definition of judicial power (Brandy v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission). There are, however, certain indicia of judicial power: 1. The ascertainment, declaration and enforcement of the rights and liabilities as they exist, or are deemed to exist, at the moment the proceedings are instituted (Boilermakers) 2. Decisional capacity: the means and independence to determine parties’ rights (Boilermakers) 3. Binding obligations/authoritative decisions: need a binding and authoritative effect to actually enforce the decisions (Boilermakers; Huddart Parker v Moorehead). a. This is compared to an Arbitration Tribunal, where the right to appeal de novo will result in a non-binding decision as the appeal will be an entirely new hearing 4. Due process: being subject to the regular rules of evidence, the rule of law, adversarial process etc. would indicate the practice of judicial powers a. This is compared to an Arbitration Tribunal, which is not necessarily subject to these rules – i.e. has its own rules relating to the consent of each of the parties to be subject to the tribunal 5. Power of judicial review of legislative and executive action (ACP v Cth) 6. Power to determine criminal guilt (Chu Keng Lim v Minister for Immigration; Polyhukovich v Cth) 7. As guaranteed by SOP, Ch III courts will not take instructions from the legislature regarding the manner in which their jurisdiction will be exercised, or the result of the case (Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration; Kable v DPP) Chapter III courts also enjoy particular implied or inherent powers that are incidental to judicial activity: 1. To determine what practice and procedure should be adopted in exercising its jurisdiction (Nicholas v The Queen) 2. To refuse to exercise its jurisdiction where to do so would be contrary to law or would involve the court in sanctioning fraud or oppression, or would permit parties to participate in an abuse of process (Pasini v United Mexican States) 3. To grant bail as an incident of the exercise of their jurisdiction under s 75 4. To compel the appearance of persons 5. To commit for contempt of Court 66 Arguably the most significant judicial powers relate to the binding aspect of the decision, and the determination of guilt. R V KIRBY; EX PARTE BOILERMAKERS ’ SOCIET Y OF AUS TRALIA (1956) 94 C LR 254 Facts: - The Arbitration Court ordered a union to comply with an award in favour of the Metal Trade Employers Association Entailed enforcing a no-strike clause The arbitration Court made a further order fining the union for contempt of the Court when it disobeyed the earlier no-strike order Issue: whether the arbitration court has the power to exercise judicial functions. Held: No Reasoning: - - - - - The Arbitration Court is established as an arbitral tribunal (note: ‘Court’ is a misleading title) pursuant to s 51(xxxv). Therefore, it cannot combine this dominant purpose of arbitration with any part of the strictly judicial power of the Commonwealth belonging solely to Chapter III Courts Judicial power is ‘concerned with the ascertainment, declaration and enforcement of the rights and liabilities of the parties as they exist, or are deemed to exist, at the moment the proceedings are instituted.’ The Arbitration tribunal was a non-judicial body because: - Arbitrator only appointed with consent of the parties - Arbitration ascertains but does not enforce what arbitrator considers ought to be the rights and liabilities between the parties Two qualities of Courts must be maintained: - Decisional capacity: means and independence to determine parties’ rights; - Ability to pass binding obligations: means to enforce this determination Appealed to federalism to determine the three qualities of the Court: - Independence: from States and Cth - Paramountcy: can settle disputes between parties - Determined sphere: to limit exactly what the Court can do and not be part of the Executive or legislature ‘The position and constitution of the judicature could not be considered accidental to the institution of federalism: for upon the judicature rested the ultimate responsibility for the maintenance and enforcement of the boundaries within which governmental power might be exercised and upon that the whole system was constructed’. On appeal to the PC: 67 - Affirmed the HC decision Lord Simmons: ‘the principle of the separation of powers is embodied in the Constitution…Ch III while affirmatively prescribing in what courts the judicial power of the Cth may be vested and the limits of their jurisdiction, negative the possibility of vesting such power in other Courts or extending their jurisdiction beyond these limits’ Boilermakers established three limbs: 1. Judicial powers may only be exercised by Ch III courts (ACTIVATED BY NON-CH III COURTS EXERCISING JUDICIAL POWER) 2. A. Ch III Courts may only exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth (ACTIVATED BY CH III COURTS EXERCISING STATE JURISDICTION) B. Ch III Courts cannot exercise powers that are non-judicial (ACTIVATED BY CH III COURTS EXERCISING NON-JUDICIAL POWER) These limbs will be explained in detail below. LIMBS DRAWN FROM BOILERMAKERS LIMB 1: THE JUDICIAL POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH CAN ONLY BE VESTED IN A CHAPTER III COURT Under the first limb of Boilermakers it has been determined that exclusively judicial power may only be vested in a Court which qualifies as a Ch III Court. Specifically, qualification as a Ch III Court is restricted under s 71: Section 71: Judicial Power and Courts The judicial power of the Commonwealth shall be vested in a Federal Supreme Court, to be called the High Court of Australia, and in such other federal courts as the Parliament creates, and in such other courts as it invests with federal jurisdiction. The High Court shall consist of a Chief Justice, and so many other Justices, not less than two, as the Parliament prescribes. Essentially, the principle raised under Limb 1 is: judicial power must only be exercised by Ch III Courts. This limb raises two issues, namely: 1. What happens when administrative bodies exercise judicial power? 2. What happens when the Executive engages in detention without judicial determinations of guilt? 68 ADMINISTRATIVE BODIES EXERCISING JUDICIAL POWER In some instances, and arbitration tribunal may seek to exercise judicial functions under the pretence of acting as a Court. This is because there are certain advantages to a Tribunal, such as: 1. They are flexible and more adaptive to changing circumstances than a Court 2. They are more speedy and efficient 3. They avoid the onerous tenure required by s 72 – i.e. a Judge will have tenure until they are 70 The disadvantages of a tribunal, however, are that there is no guarantee of independence and impartiality in decision making, as judges do not enjoy the security of tenure guaranteed by s 72; likewise, tribunals are not subject to the strict nature of judicial process – exposing the process of a tribunal to potential lack of fairness. Where bodies established under s 51(xxxv) as an Arbitration Tribunal, they will not be permitted to exercise judicial power (as listed/outlined above) that is specifically reserved for Ch III courts. Therefore, an administrative body exercising judicial power will be contrary to s 72. EXECUTIVE DETENTION An issue arises in relation to the executive branch implementing orders for detention. This is because detention is generally a punishment and must follow a judicial decision. However, some forms of executive detention are allowed – i.e. quarantine, enemy aliens in wartime, asylum seekers pending application for refugee status. The question to be asked in relation to executive detention is whether the detention is implemented for punitive or not. Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration (1992) 176 CLR 1 Facts: - The Migration Act 1958 (Cth) ss 54L and 54N (in Div 4B) provided for the detention of a ‘designated person’ (essentially non-citizen asylum seekers) This detention would be effective until either removed from Australia or given an entry permit Issue: was this an exercise of judicial power contrary to Ch III of the Constitution? Held: No, not a law contrary to SOP constituted valid executive detention Reasoning: - Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ: 69 - - Some functions have been established as being ‘essentially and exclusively judicial in character’ the most important is the judgement and punishment of criminal guilt under a law of the Commonwealth - Central concern surrounding judicial act being a form of punishment executive cant punish in this way and cant’ arbitrarily detain (i.e. detaining in the absence of judicial adjudication) essentially citizens are ‘immune’ from detention in custody without a determination of guilt Gaudron said that ‘detention in custody in circumstances not involving some breach of the criminal law…is offensive to ordinary notions of what is involved in a just society’ - However, the Court determined exceptions, in particular: i. To arrest and detain pursuant to a warrant (although this is ordinarily subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the Court ii. Involuntary detention for mental illness or infectious disease iii. Any matter which is not punitive in nature - Established a test: i. The law must authorise detention ‘reasonably capable of being seen as necessary for the purpose of deportation or necessary to enable an application for an entry permit to be made and considered’ ii. The law must not be ‘punitive in nature…nor part of the judicial power of the Commonwealth’ - In this case, the provisions of the Act were therefore valid because detention was for a limited period and, critically, the detainee always had the power to end their detention by asking to be removed McHugh J: - A person is not being punished if…they choose to be detained in custody pending the determination for an application for entry’ Al-Kateb v Godwin (2004) 219 CLR 562 Facts: - - S 189(a) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) – required the detention of unlawful citizens Under s 196(1), Al-Kateb was to be detained until he was: c. Removed from Australia, or d. Deported, or e. Granted a visa Under s 198(1), he must be removed as soon as practicable if he asks to be Al-Kateb was therefore being detained under MA, stateless and faced prospect of indefinite detention No country would take him Issues: 1. Did the legislation authorise indefinite detention? Should/could the words be read consistently with fundamental rights? 2. If indefinite detention was authorised, did this executive detention contravene Ch III of the Constitution (the federal executive exercising the judicial power of the Commonwealth? 70 Held: 1. Didn’t expressly consider this. 2. No, in accordance with Lim Reasoning: - He was not detained for an offence – the consequence came about as a result of a range of circumstances Dissent: - - Gleeson CJ: - Relied on principle of legality - ‘Courts do not impute to the legislature an intention to abrogate or curtail certain human rights or freedoms (of which personal liberty is the most basic) unless such an intention is clearly manifested by unambiguous language, which indicates that the legislature has directed its attention to the rights or freedoms in question, and has consciously decided upon abrogation and curtailment’ - There are two options for interpreting the removal power under the Act when the removal can’t be completed: i. Treat detention as suspended ii. Treat detention as indefinite - Favoured the former – suspended – because of principle of legality, minority encouraged towards interpretation because detention is mandatory not discretionary – if the legislation provided that executive could review detention or had to periodically, they would be more likely to say that ID was allowed Kirby: - ‘Indefinite detention at the will of the Executive, and according to its opinions, actions and judgments, is alien to Australia’s constitutional arrangements’ - Points to international law an common law presumptions against indefinite detention, in favour of presumptions of personal liberty i. ICCPR arts 7, 8 and 9 The general principle is: the involuntary detention of a citizen in custody by the State in penal or punitive in character and, under our system of government, exists only as an incident of the exclusively judicial function of adjudging and punishing criminal guilt. However, there are exceptions: - - If detention is to ensure that a person accused of a crime is available to be dealt with by the courts (Lim) - Essentially, the ensure the smooth functioning of the judicial process The delegation of judicial functions to administrative officers of the courts is permissible, provided it is limited and subject to the review of the Courts: (Harris v Caladine) 71 - Involuntary detention in cases of mental illness or infectious diseases as it is imposed by the legislative to protect the community, not as a punishment of the Court (Lim) Parliament can punish for contempt of Parliament (Australian Constitution s 49) Military tribunals may punish for breach of military discipline per the defence power s 51(vi) (Re Tracy) Detention for a legitimate, non-punitive purpose can be authorised by legislation (Lim; AlKateb) - Negative consequences of detention will not make it punitive, it is the intention that is important - Detention will not be punitive even if it were indefinite – the harsh reality of the detention will not render it illegitimate (Al-Kateb) LIMB 2: CHAPTER III COURTS CAN EXERCISE ONLY THE JUDICIAL POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH This limb is further divided into two sub-limbs: a. Chapter III courts can exercise only the judicial power of the Commonwealth; and b. Chapter III courts can exercise only the judicial power of the Commonwealth. This limb (and it’s sub-limbs) raises three questions, namely: 1. What happens when Federal Courts are given State power? 2. What happens when making interim control orders? 3. What happens when non-judicial roles are given to judges? LIMB 2A: CHAPTER III COURTS MAY NOT EXERCISE JUDICIAL POWER THAT IS NOT THE ‘JUDICIAL POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH’ Section 77(iii): Power to define jurisdiction With respect to any of the matters mentioned in the last two sections the Parliament may make laws:…investing any court of a State with federal jurisdiction. While s 77(iii) allows the Parliament to vest States with federal jurisdiction, there is no mention of vesting federal courts with State jurisdiction. Under this limb of Boilermakers the Parliament is not permitted to vest State jurisdiction in federal courts. For example, it is illegitimate for a Ch III court to hear matters relating to State corporations. Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally (Cross-vesting Case) (1999) 198 CLR 511 Facts: 72 - - As part of the national corporations scheme instigated after the High Court ruling in New South Wales v Commonwealth (1990), the States were required to legislate for the formation of corporations As a result, the States had to vest the Federal Court with State jurisdiction to allow the Commonwealth to have effective judicial control over corporations law Issue: Can Ch III courts exercise State jurisdiction? Held: No Reasoning: - Ch III doesn’t provide for establishing courts that can exercise State jurisdiction or State judicial power, nor words to indicate States can do such vesting McHugh J: took a textualist approach to interpretation Dissent: - Kirby: - ‘There would not seem to be any reason of constitutional principle or policy to forbid the kind of legislative cooperative scheme between all of the governments and legislatures of the Commonwealth instanced by the two legislative systems of cross-vesting’ LIMB 2B: CHAPTER III COURTS CANNOT EXERCISE NON-JUDICIAL POWERS Under Limb 2B of Boilermakers, those Courts vested with federal jurisdiction pursuant to Ch III cannot exercise powers that are non-judicial. In essence, this prevents Ch III courts from exercising both types of powers, namely: judicial and non-judicial, at the same time. However, non-judicial functions may be assigned to a judge in their personal capacity. PERSONA DESIGNATA This is seen as an executive role, often done ex parte (i.e. parties may be absent). The general problem with this role is that it is potentially unreviewable – hence why it is seen as going against the judicial role of the Ch III courts. However, as stated by Drake v Minister for Immigration & Ethnic Affairs (1979), such appointments don’t involve impermissible attempts to confer on a Ch III court functions that are antithetical to the exercise of judicial power – in fact, this case claims that it does not involve conferring any functions at all on the Courts. Scepticism: Hilton v Wells (1985) was sceptical of the role. Specifically, Mason and Deane JJ argued that, ‘conformably with underlying concept of SOP, it is beyond the power of Parliament to attach to the holding of judicial office as a member of a Ch III Court an unavoidable obligation to perform as a designated person, detached from the relevant court, administrative functions unrelated to the exercise of the jurisdiction of that Court.’ 73 Grollo v Palmer (1995) 184 CLR 348, 364 This case established 2 conditions which are required to be able to confer non-judicial functions on judges as designated persons: 1. Consent from the judge themselves; and 2. The function must not be incompatible with either: (explored below in Wilson) a. The judge’s performance of their judicial functions, or b. The proper discharge by judiciary of its responsibilities as an institution exercising judicial power The following case deal with the second rule outlined in Grollo: Wilson v Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs (1996) 189 CLR 1 Facts: - - Justice Matthews – judge of the Federal Court – appointed by the Minister to prepare a report under s 10 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth) – considering impact of the Hindmarsh Island bridge development The Minister had the power to make declarations for the protection of land; the Minister receiving a report was a pre-condition Issue: was the appointment incompatible with her properly discharging her judicial function, or with the judiciary properly discharging its responsibilities as an institution exercising judicial power? (i.e. second rule in Grollo) Held: Yes – incompatible with the constitutional independence of the judiciary from the executive government Reasoning: - - Emphasis on link between SOP and public confidence Also emphasised the closeness of the report function with the executive It is important to differentiate between circumstances where function are performed independently or under instruction, and whether the function entails observing hallmarks of judicial process In this case: the report was merely a condition precedent of the Minister’s action – it was not an independent review If allowing it – Justice Matthews would be ‘in a position equivalent to that of a Ministerial adviser’ The Report would entail balancing competing interests – rather than a judicial function it was a political function Would require giving the executive advisory opinions on law (rather than determining rights and liabilities of existing parties) Dissent: - Kirby: - Clear differentiation of roles - This role is not incompatible with being a judge 74 - The appointment necessarily asks for Justice Matthews’ objectivity and detachment, as the qualities of a judge This is something we should permit as a strength – would allow the flexibility of novel roles that benefit from judicial experience INTERIM CONTROL ORDERS These can be made by a federal judge and restrict freedom of an individual short of actual imprisonment and in circumstances where the individual has not been found guilty of a criminal offence. Question to ask: are these non-judicial powers and thus incompatible with the principle that Ch III Courts cannot exercise non-judicial powers. Thomas v Mowbray (2007) 233 CLR 307 Facts: - - - Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) div 104 – power to issue control orders Purpose of ‘protecting the public from a terrorist act’ An order could impose restrictions on a person, including: - The person shall be in a specified place and report to specified persons, or remain in specified premises at specified times and periods; - Wear a tracking device - Not use specified forms of telecommunication or other technology, and not communicate or associate with specified individuals Judge could make the order where satisfied on the balance of probabilities that, inter alia (s 104.4): - Making the order would substantially assist in the preventing of a terrorist attack, or - That the person has provided training to, or received training from, a listed terrorist organisation, - And: the judge is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that each of the obligations, prohibitions and restrictions to be imposed on the person by the order is reasonably necessary and reasonably appropriate and adapted, for the purpose of protecting the public from a terrorist act’ Thomas had a control order imposed on him by the FC and challenged the constitutional validity of the provisions Argued the provisions conferred non-judicial power on Ch III courts because they authorised the court to: - Declare new rights, not merely to declare existing ones under the law - Exercise discretion pursuant to non-legal criteria; and - Take into account public policy considerations 75 - Thus, interim control orders were an executive or legislative power Issue: whether the provisions were valid pursuant to the second limb of Boilermakers Held: Yes – the provisions were valid Reasoning: - - In relation to the argument that the ICO declare new rights and obligations, nor merely used to declare existing ones under the law: - Gleeson CJ: i. Agrees with Thomas but says this is allowable ii. ICOs give power to interfere with liberty based on what persons may do in future and not based on judicial determination of what the person has done iii. Entails creating new legal obligations not resolving a dispute about existing rights and obligations iv. However, this power has been exercised by courts in many circumstances 1. Example: Bail and AVO – the latter have their origin in the ancient power to justice and judges to bind persons over to keep the peace v. Thomas’ argument would require that the order can only be exercised by the Executive branch vi. It is essentially a ‘matter’ exercising the Commonwealth judicial power because it bears the same ‘jurisprudential character’ (McHugh in Fardon) as powers historically exercised by the Court In relation to the argument that the order was determined on the basis of non-legal criteria: - The statute required determination of whether the ICO was ‘reasonably necessary’, ‘reasonably appropriate and adapted’, to the purpose of protecting the public from attack - Court drew analogies with ‘just and equitable’ property settlements in family law where discretion isn’t consistient with the exercise of judicial power Court is familiar with such standards from other forms of statutory protection orders e.g. AVOs - Where legislation is designed to effect policy, and then the Courts are called on to interpret and apply that law, inevitably consideration of that policy cannot be excluded from the curial interpretative process - ‘From consideration of the legislation on a case by case basis it may be expected that guiding principles will emerge, a commonly encountered phenomenon in judicial decision-making’ thus not simply enacting legislative plan to control certain persons Dissent: - Hayne J: - Indeterminacy of ‘for the purpose of protecting the public from a terrorist act’ sets this apart from the exercise of judicial power it does not entail ‘any familiar judicial measure’ - ‘It is a criterion that seeks to require federal courts to decide whether and how a particular order against a named person will achieve or tend to achieve a further consequence: by contributing to whatever may be the steps taken by the Executive, through police, security, and other agencies, to protect the public from a terrorist act’ 76 - Fundamental concern: Court not involved in a judicial exercise not determining rights and liabilities of parties based on facts/law – rather, Court being brought into Executive’s plan to control people/political acts In relation to the making of control orders, the following comment made by the majority in Lim is relevant: “A law which authorised or required federal judicial power to be exercised in a ‘manner which is inconsistent with the essential character of a court or with the nature of judicial power’ would be invalid” suggestion relating to procedural fairness NON-JUDICIAL POWERS GIVEN TO JUDGES The question is: whether non-judicial powers can be exercised by State Courts on the basis that State Constitutions do not contain the SOP doctrine. Alternatively, would the exercise of non-judicial powers be permitted in State Courts on the basis of no SOP doctrine in State Constitutions. In answer to this, the dominant principle was established by Kable and states that: there is no distinct SOP doctrine in State constitutions, however State courts are part of the national judicature, therefore can only exercise non-judicial functions that don’t substantially impair the Court’s institutional integrity. Kable v DPP (NSW) (1996) 189 CLR 51 Facts: - - Kable in prison for murdering wife Sending threatening letters to her family members from inside prison NSW passed Community Protection Act 1994 (NSW) to keep him in prison - Under law, Court can order that a specified person be detained for a specified period if satisfied on reasonable grounds that likely to commit serious violence or appropriate for protection that he be held in custody - DPP would make application and Court decides on balance of probabilities whether likely to commit serious violence - Could be detained for up to six months and applications are renewable (s 5(3)) The Bill amended to specifically target Kable Issue: does the legislation impose an impermissible non-judicial function on the Court? Held: Yes Reasoning: - Discussion on what characteristics must State courts exhibit to maintain institutional integrity: - McHugh: 77 - - i. Natural justice: parliament can’t legislate for court to disregard rules of natural justice when exercising federal judicial power ii. Independent from executive: must be, and must be perceived to be, independent from the legislature and executive Discussion on how Court can lose its identity as a Court: - If it is granted non-judicial powers of a governmental nature that undermine its character example: determining how much of State budget should be spent on welfare this would ‘have the effect of so closely identifying the Supreme Court with the government of the State that it would give the appearance that the Supreme Court was part of the executive government’ The problematic features of the legislation in this case: - Only determination required was that they were satisfied on reasonable grounds that the detainee is ‘more likely than not’ to commit serious violence this is a lower standard than usual for criminal offences - Court could determine the application in the absence of the detainee (i.e. ‘open court’) - The object of the legislation was to detain Kable ‘not for what he has done but for what the executive government fear he might do’ - The ad hominem character of the Act meant that the ‘executive which introduced the Act…passed the Act for the purpose of ensuring the appellant was kept in prison’ Fardon v A-G (Qld) (2004) 223 CLR 575 Facts: - Dangerous Prisons (Sexual Offenders) Act 2003 (Qld) allowed Courts to make orders detaining prisoners indefinitely if satisfied of unacceptable risk of future serious sexual offence Application by A-G, on notice to the current prisoner (i.e. open hearing ss 5 and 6) Must do so on the basis of ‘acceptable, cogent evidence’ and only where satisfied to a high degree of probability (s 13(3)) The paramount consideration is ‘the need to ensure adequate protection of the community’ (s 13(6)) Issue: whether the legislation imposed impermissible non-judicial functions on the Court. Held: No Reasoning: - While the preventative detention was not punitive, and therefore a non-judicial function, it did not disrupt the integrity of the Court This was because ‘the act displayed the hallmarks of traditional judicial forms and procedure’ - Evidentiary threshold: the high degree of probability threshold was based on rules of evidence - Prison was allowed to adduce evidence and make submissions - Discretion was allowed in realtion to making the order and how the judge wanted the order to apply - Determined that no reasonable person would consider the Queensland SC might not be impartial 78 - Applying preventative detention against a class of offenders (generally serios sex offenders) currently about to be released from prison is permissible, so long as the process displays the hallmarks of tradition judicial adjudication – evidence, open hearing, discretion to impose. Dissent: - Kirby: - ‘forbids attempts of State Parliaments to impose on Court, notably Supreme Courts, functions that would oblige them to act in relation to a person in a manner which is inconsistent with traditional judicial process’ Comparison of Kable and Fardon: the question is whether Fardon is an extension of Kable or whether the decision is incompatible with Kable - Generally believed that the decision is compatible, and therefore an extension of Kable - Cases that reject incompatibility claims (incompatibility is permissible) i. Assistant Commissioner Condon v Pompano ii. A-G (NT) v Emmerson iii. Kuczborski v State of Qld iv. North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency v NT - Cases that accept incompatibility claims (that incompatibility is impermissible) i. SA v Totani ii. Wainohu v NSW SA v Totani (2010) 242 CLR 118 Facts: - SA law allowed for AG to make declaration outlawing an organisation on basis of any info suggesting connection to serious criminal activity (e.g. bike gangs and drug dealers) Declaration of a criminal organisation mandated, upon application by the Commissioner of Police, a judicial control order against a member of such an organisation Proceedings were ex parte – i.e. those subject to the control order were not present SA court must make order if satisfied person is a member of the organisation Would be prohibited from associating with other members of having weapons If you break the control order you can go to jail Issue: whether the Court is exercising a judicial role. If not, is this role incompatible with being a repository of federal jurisdiction? Held: Yes – it was a non-judicial power that was incompatible with its role. Reasoning: - Non-judicial power because the Court was not required to make a determination of rights and liabilities, and entailed no discretion The function substantially impaired on the institutional integrity because the court was making no determination of rights or liabilities the Court was merely rubber stamping executive action without any substantive judicial function 79 - It was significant that the Court is not independent Dissent: - Heydon J: if legislation wasn’t valid, States may just make these orders themselves and not involve the courts – this would have the perverse effect of diminishing civil liberties - Counter-argument: we are not concerned with future consequences (this draws a parallel with WorkChoices) North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency v NT [2015] HCA 41 (11 November 2015) NOTE: This case has the potential for review Facts: - - S 133AB of the Police Administration Act (NT) allowed: - Arrest without warrant for offences for which an infringement notice could be issued - Could hold in custody for up to four hours; longer if intoxicated - Person to be released, released with infringement notice, released on bail or brought to Court Infringement offences include things like disorderly conduct, failing to keep yard clean and creating nuisance or offensive smell, or failing to comply with liquor licence conditions If a person is detained, they must be brought before Court in a reasonable time (s 137) Issue: was this a punitive power to detain? Held: No Reasoning: - - Not punitive because: - Person is available to be dealt with in respect of an offence if necessary; - Preserve public order - Prevents offending - Prevents harassment - Prevents fabrication of evidence - Prevents safety and welfare of public and person detained However, suggested that if period before coming before court was ‘significantly greater’ it may be punitive Dissent: - - Statute aimed at depriving liberty and there was no obligation to bring the person before a court Citing Lim: ‘exceptional cases’ aside, ‘the involuntary detention of a citizen in custody by the State is penal or punitive in character and, under our system of government, exists only as an incident of the exclusively judicial function of adjudging and punishing criminal guilt’ Any form of detention is punitive unless justified otherwise otherwise, detention must be reasonably necessary to effectuate non-punitive purpose; duration be capable of objective determination by Court at any time and from time to time 80 Wainohu v NSW (2011) 203 CLR 181 Facts: - Law allowed judges of SC to make declarations that organisations were criminal Judges could do so without giving reasons Held: Court said it gave right to inscrutable decision making – thus incompatible with being repository of federal jurisdiction Assistant Commissioner Condon v Pompano (2013) 252 CLR 38 Facts: - Concerned applications against bike type figures which could be made using criminal intelligence through this intelligence was secret and confidential thus heard in absence of other party Held: Open Court principle may be qualified in certain situations Reasoning: - Emphasised that SC has an inherent power to refuse to act in cases of unfairness – it wouldn’t hear D’s case if D’s lack of presence was unfair A-G (NT) v Emmerson (2014) 253 CLR 393 Facts: - Drug traffickers losing all their property after two offences regardless of whether property related to the offence Held: forfeiture orders not novel and are subject to adjudicative standards thus permissible Kuczborski v State of Qld (2014) 254 CLR 51 Facts: - Challenge to several statutes clamping down on bike gangs Criminal organisation to be determined by Court order or by executive – Minister could have regard to any relevant info in making decision Issue: whether the declaration was a non-judicial function. If so, is it impermissible? Held: Legislation was permissible Reasoning: - Judicial decision was not repugnant to institutional integrity of Courts and executive/legislature were not engaging in judicial acts French CJ: distinguished from Totani because Totani did not involve judicial adjudication – rather, a control order was required upon application Majority considered that merely pointing out the severity of the law does not engage the Kable prohibition 81 TEST TO BE APPLIED I N EXAM Two part Test: 1. What is the power being exercised? [NB – Decisions are fact specific, there is no one principle despite appearance from Kable, Kuczborksi v State of Queensland). a. Is it judicial? i. Outline the judicial powers (as under Brandy?) ii. What are the concerns i.e. are there ones that look like judicial powers but not entirely sure. iii. If it is judicial, this will be a concern for Limb 1 iv. If it is a non-judicial power, this will be a concern for Limb 2B b. If it's detention – Limb 1 i. Is it punitive in purpose? ii. Lim principle 2. Where is the power being used? a. Is it a chapter III court? i. Outline who are the chapter III courts ii. If it is not, and the power is judicial Limb 1 iii. If it is, and the power is non-judicial Limb 2 b. If it is a Federal Court with State jurisdiction, and the power is judicial Limb 2a c. If it's a State Court with federal jurisdiction, and the power is judicial: i. Limb 2b: is the exercise of the power impairing the institutional integrity of the Courts (Kable) – repository of federal jurisdiction? If it is a non-Chapter III Court exercising judicial power Limb 1 If it is a Federal Chapter III Court exercising State judicial power Limb 2a If it is a Chapter III Court exercising non-judicial power Limb 2b 82 Chapter 3 Courts Does the Commonwealth act create a court? Is constituted in accordance with Chapter 3? Yes Judges must have tenure s72 Judges may not be removed Yes No Judges must have fixed remuneration No Is it exercising the Judicial Power of the Commonwealth? No Chu King Lim v Minister for Immigration The power to make Binding, Authoritative and Conclusive decisions Brandy v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Yes Invalid Does the c’th act create a tribunal that is not a Ch3 court? The power to determine innocence or guilt Valid Lutton v Lessels Is it exercising the judicial power of the commonwealth? Yes Yes No Are the members of the tribunal Ch3 judges? Yes No Are the judges acting in their personal capacity or as judges? Personal Capacity Judicial capacity Are the judges acting in persona designata acting in a manner incompatible to being a judge? Invalid Grollo v Palmer Valid 83 EXPRESS RIGHTS AND A BILL OF RIGHTS PROTECTION OF RIGHTS HOW In Australia, rights are protected through two instruments: statute and common law. Statute: - Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth) - Scrutiny of incoming legislation with international materials RDA 1975 (Cth) and Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) - External affairs ICCPR - Individuals who claim their rights have been violated may submit a written complaint to the Human Rights Committee of the UN - Leaves to national government whether and how to respond Common law: - Habeas corpus: freedom of the body Right to silence, representation, to vote, freedom of speech in parliament Right against arbitrary executive action Principle of legality - Al-Kateb: Courts do not impute an intention to curtail certain human rights or freedoms unless such an intention is clearly manifested by unambiguous language must interpret with fundamental freedoms AMENDMENT PROPOSALS 1942: Wartime Constitutional Convention: - - Suggested power to make laws to guarantee the four freedoms - Freedom of speech and expression, religious freedom, freedom from want, freedom from fear Suggested not a guarantee of rights rather a power to legislate to guarantee such rights against state legislation Ultimately not included in the referendum 1973: Human Rights Bill - Lionel Murphy as A-G attempted Bill to implement ICCPR 84 - Basid idea – State legislation inconsistent with Cth Act would have been invalid under s 109 (inconsistency) Framed as being enforceable against governments and the private sector 1985: Human Rights Bill + Constitutional Commission and 1988 referendum - Proposal to extend right to trial by jury, freedom of religion and acquiring property on just terms MODELS OF HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTIONS CONSTITUTIONAL MODEL US Constitution: This model is the basis of the US Constitution – Supreme Court can strike down any legislation inconsistent with the Bill of Rights. Canadian Constitution: Canadian legislation that is inconsistent will be inoperative; s 33 override clause: may declare that inoperative legislation will apply notwithstanding rights in the charter. PARLIAMENTARY MODEL This is the Commonwealth model – also known as the dialogue/interpretive model. Examples: - New Zealand BOR Act 1900 Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT) + Charter of Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) - No express reference to what responsibilities are; although some rights can carry this The above are understood to be dialogue models of BOR: - ‘Document would have legal force, its primary purpose would be to encourage the development of a human rights culture’ (Towards an ACT Human Rights Act: Report of the ACT Bill of Rights Consultative Committee (Department of Justice and Community Safety, 2003)) Within Parliament: - HRA (ACT): - S 37: On the introduction of bill, the AG must prepare a compatibility statement – whether inconsistent with the protected rights in the HR Act - S 38: Parliamentary committee must then report on any human rights issues raised by the law - This doesn’t impact on legislature’s ability to pass laws but is simply a trigger for raising HR compatibility issues. Precipitates political conversation on suitability 85 COURT ASSESSMENT UNDER THE DIALOGUE MODEL: 1. Interpretation Involves interpretation of the legislation that is understood to be inconsistent - Under DM, courts must adopt a rights-consistent interpretation - E.g. territory law must be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights per Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT) s 30 Morse v The Police [2011] NZSC 45 Facts: - M protesting NZ involvement in Afghanistan, set fire to flag at ANZAC day Dawn Parade service Charged with behaving ‘in an offensive or disorderly manner…in or within view of a public place’ Offensive and disorderly – ambiguous Court required by BOR to adopt option that is consistent with freedom of expression Hopkinson v Police [2004] 3 NZLR 704 (HC) Facts: - Another protestor lit flag on fire Court had to decide meaning of intending to ‘dishonour the flag Held: decided that ‘dishonouring the flag’ could mean many things but consistent with freedom of expression, burning during protest is not dishonouring – if he had urinated then probably Significance of the above cases: rights consistent interpretation has the potential to constrain parliament or at least make Parliament express itself very clearly on what it is trying to prohibit. 2. Proportionality Courts required to assess whether the limitations imposed are justified. - - Consider: how do we determine whether an Act is compatible with human rights? NZ BOR Act 1900 s 5: - ‘Rights may be subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society’ - Freedom of expression is limited by reasons that can be justified in a free and democratic society - This follows ICCPR art 18 ICCPR Art 18: - Right is subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights or freedoms of others 86 - E.g. Shambo a sacred cow in Hindu community in Walves government ordered he be slaughtered because he had bovine tuberculosis Court faced with the balancing exercise and found that the killing of the Cow was necessary because the right gave way to public health interest 3. Declarations Courts can issue declarations stating that a law is inconsistent with a relevant human rights act. - - This power conferred for example by the Charter of Rights and Responsibility Act 2006 s 36 Doesn’t affect the validity of legislation but acts as a warning to Parliament who can amend it P stays in control but Court and P are in dialogue It is significant that every time declarations of inconsistency have been made in the UK, legislation has been changed by Parliament not clear as to how effective the remedy is, but we are still seeing a human rights dialogue compels review In ACT: AG has 6 month to prepare a response to declarations of incompatibility s 33(3). INTERPRETATIONS OF THE DIALOGUE MODEL: - - - ‘Judicial decision is open to legislative reversal, modification or avoidance’ (Peter Hogg and Allison Bushell, ‘The Charter Dialogue between Courts and Legislators (or perhaps the charter isn’t such a bad thing after all)’ (1997) 35 Osgoode Hall Law Journal 75) Reflecting expertise (court) and democratic mandate (parliament) – (Alison Young, Parliamentary Sovereignty and the Human Rights Act (Hart Publishing, 2009)) - Court is the best place to consider rights and freedoms - As opposed to considering policy objectives – parliament takes a broader social perspective (Waldron 1360) It accounts for disagreement on: 1. Nature and identification of rights 2. How abstract rights apply to legislation a. Whether legislation is inconsistent with rights declared 3. How abstract rights apply to specific cases TOWARDS A HUMAN RIGHTS ACT IN AUSTRALIA? Brennan Committee (2008): - Canvassed views for options for human rights, including the sovereignty of the parliament, and did not include a constitutionally entrenched BOR Generated the National Human Rights Consultation Report (2009) - In favour of national law - Rudd government rejected HRA – said that it was ‘divisive’ concern: shift of power further towards the judiciary under a HR act 87 - Instead, government developed human rights framework which was central to the Act below Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth) - Ss 8 and 9: - Legislation passed by federal parliament to be accompanied by a statement of compatibility - This designed it assess whether laws are inconsistent with international instrument/human rights - Defines human rights in s 3(1): rights recognized by seven listed international instruments e.g. ICCPR, ICESCR - Failure to comply with the compatibility statement doesn’t affect the law’s validity, operation or enforcement of the Act - Statement of compatibility will not bind any court or tribunal Momcilovic v The Queen (2011) 245 CLR 1 Facts: - - Concerned Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 (Vic) s 5 S 5: this provided for a reversal of the presumption of innocence - if drugs were found in your home, they were assumed to be yours and the Crown wouldn’t have to prove this beyond reasonable doubt accused would bear the onus of proof This was contrary to presumption of innocence and other rights in Victorian Charter - S 25: presumption of innocence - S 32: statutes to be read consistent with rights so far as possible - S 7: proportionality - S 36: declaration of inconsistent interpretation can be issued Issues: 1. Did s 32 and 36 of the Charter impermissibly confer functions on the Vic SC contrary to Ch III of the Constitution? (Kable) 2. Does the HC have jurisdiction under s 73 of the Constitution to hear an appeal from a declaration of inconsistent interpretation? Discussion: - - Given a state SC was exercising (arguably) a non-judicial power, it raised a question in Kable – was the declaration power a judicial power (or incidental)? - Important because under CH III, state courts can exercise non-judicial power as long as it isn’t incompatible with being a repository of federal jurisdiction (Kable). French CJ: - Interpretation provision was carried out in course of judicial function - Ability to make declarations doesn’t affect rights and liabilities or the statutory provision itself - Not incidental to judicial power (a non-judicial power) therefore permissible 88 - - Declarations manifest limitations on courts – it is parliament’s responsibility to determine whether laws are inconsistent with human rights they don’t affect SOP as P maintains authority to keep legislation or change it Declarations don’t encourage dialogue because P can acknowledge/respond or ignore the declaration – they have no legal impact and reinforce limitations on courts NOTE: I disagree with French he disregards the fact that while the P can ignore declarations, it encourages dialogue merely by illuminating the existence of an issue – it’s like the issue of striking impermissible evidence from the mind of the judge’s – it is impossible to pretend they have not heard something Dissent: - - Gummow J: declaration power is fundamentally an advisory opinion – that funamdentally changes the relationship between the Court and the legislature – by providing advice, it disrupts the role of the court (an overtly political action) Heydon J: - Proportionality review engages in compelling the redefinition of a right - Interpretation provision – caused substantial re-writing of statutes - Declaration steps outside the constitutional concept of a court by offering advice - All those non-judicial functions create an incompatibility between the SC undertaking functions and being a depository of federal jurisdiction - ‘The odour of human rights sanctity is sweet and addictive. It is a comforting drug stronger than poppy or mandragora or all the drowsy syrups in the world. But the effect can only be mainained over time by increasing the strength of the dose.’ Significance of Momcilovic: - - - majority said that a declaration of inconsistency power is a non-judicial power - this is an issue because Boilermakers said that Ch III courts can only exercise judicial functions Thus, any declaration by a Sttae SC could not be appealed to the HC because HC can’t hear non-judicial functions HC can hear decrees, orders, sentences and matters (ss 73-77) and declarations aren’t in any of these categories Thus, it is unlikely that power to hear declarations could be conferred on the HC by a national BOR - Not judicial and not incidental to the judicial power - Only way to involve the HC would be through constitutional amendment Consider: Are human rights the most appropriate language for making decisions? 89 FREEDOM OF RELIGION Section 116 Commonwealth not to legislate in respect of religion The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth. Note: nothing in this section prevents a state from legislating with respect to religion, e.g. by requiring a religious test for public office. MEANING OF RELIGION Church of the New Faith v Commissioner of Pay-Roll Tax (Vic) 1983 CLR 120 Issue: Was the church of scientology a ‘religious institution’ entitled to exemption from payroll tax under Victorian law? Substantive view: - - Mason and Brennan J: religious requires: 1. First, belief in a supernatural being, thing or principle 2. Second, acceptance of canons of conduct in order to give effect to that belief Consider a definition by SC of Canada: - ‘In essence, religion is about freely and deeply held personal convictions connected to an individual’s spiritual faith and integrally linked to one’s self-definition and spiritual fulfilment’ (Amselem). Analogical view: - - Wilson and Deane JJ: identifying religion involves reasoning by analogy i.e. requires ‘an empirical observation of accepted religions’ The point is to develop/discover either: - Indicia of religion: i. Supernatural; relationship of humanity to the supernatural; codes of conduct; identifiable group; rituals etc. - Functional equivalents: i. Here we look at the functions of religion as a provision or meaning of harmonised order ii. The question is: what, by analogy, functionally provides similar functional qualities for an individual person? Problems with this view: 90 - We need to identify known and accepted religions Do civic religions (e.g. Marxism, environmentalism) provide functions like meaning etc. Consider the purpose of Freedom of Religion: Instead of the above theological questions, the best approach is to consider the purpose of freedom of religion. - S 116 ensures liberty and protection against other majority traditions - For the seventh day Adventists at Federation, it prevented uniform law requiring observance of the Sabbath on Sunday because they, as a minority, preferred Saturday. MEANING OF A LAW ‘FOR PROHIBITING THE FREE EXERCISE’ OF ANY RELIGION Krygger v Williams (1912) 15 CLR 366 Facts: - Concerned conscientious objection Defence Act 1903 (Cth) requiring compulsory peace-time military training S 13(3): all persons liable to be trained…who are forbidden by the doctrines of their religion to bear arms shall so far as possible be allotted to non-combatant duties Held: the real objection taken by the appellant is not to be trained, but to be trained so in time of the war he may be competent to saving life. Adelaide Company of Jehovah’s Witnesses Inc v Commonwealth (1943) 67 CLR 116 Facts: - Concerned legislation allowing GG to declare a body corporate prejudicial to war effort and unlawful. - Once declaration was made, the body would be dissolved and their property seized. - Such a declaration was made against Jehovah’s witnesses. - J’s are pacifists and don’t want to take oaths (conflict with god). Issues and decision: 1. Did regulations fall within defence power? S 51(vi) a. Held: No: Starke J (154) regulations ‘arbitrary, capricious and oppressive’. 2. Did regulations infringe s 116? a. Held: No based on ‘public good’. Reasoning: - Latham J: - Difficult to define religion and thus the scope of the power (123). - Free exercise of religion extends to the absence of religion (i.e. not believing) (124). - There are necessary limits if someone raises their free exercise of religion against Commonwealth legislation because protection under 116 presupposes maintenance of a social order and civil society (126-7). 91 - - We must ask: i. Is the law trying to protect existence of community? ii. Is the law characterised as ‘for’ the purpose of prohibiting the free exercise of religion? (131-2). Rich J (149) - Protection under 116 not absolute, subject to restrictions essential to preserving community. Kruger v Commonwealth (‘Stolen generations case’) (1997) 190 CLR 1 Facts: - Attempt to invoke s 116 as protecting the tribal culture of Aboriginal families and communities in the NT - It was claimed that the Aboriginals Ordinance 1918 (NT) which authorized removing children was invalid as a law for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion. Issues: 1. Whether s 116 applies in the territories (decided yes) 2. Whether removing children from their communities was a law for prohibiting the exercise of freedom of religion Discussion on the meaning of ‘for’: - ‘For’ typically means a constitutionally forbidden purpose - To attract invalidity under s 116, a law must have the purpose of achieving an object which s 116 forbids [40] I.e. directly attacking religion; purpose is to forbid free religion. - The expression ‘prohibiting the free exercise of any religion’ suggests that section 116 is concerned only with laws that ban religious practices or otherwise forbid the free exercise of any religion. Held: Narrow view adopted valid because ‘no conduct of a religious nature proscribed or sought to be regulated in any way’ Gummow J 161. Reasoning: - It is necessary to determine the purpose of the legislation. A law won’t be invalid on the basis that it ‘prohibits the free exercise of religion’ even if that’s its indirect consequence but had a different, overriding public purpose or tried to satisfy a pressing social need [134]. MEANING OF A LAW ‘FOR ESTABLISHING ANY RELIGION’ Attorney – General (Vic); Ex rel Black v Commonwealth (DOGS Case) (1981) 146 CLR 559 Facts: - Regarding Commonwealth funding of education programmes through state grants some intended recipients run by religious organisations - especially the RC Church Claimed contrary to 116: cannot make a law for establishing religion. 92 - Attempted to make analogies with US First Amendment, which says congress shall make no laws respecting establishment of religion. Decision: - - Rejects argument that 116 comparable to US First Amendment (579). - Pointed to the fact that the Constitution has radically different language indicates no intention to achieve that of USA. To be invalid, the law must expressly and singularly aim to establish a religion (given the phrase is ‘for establishing any religion’) (579). Commonwealth can fund religious schools, at least on a non-discriminatory basis. What would be a law that establishes a religion? - Entrenching religion as a feature of and identified with the Commonwealth (582 Barwick). Would involve citizen in a duty to maintain it and oblige Commonwealth to protect and promote the religion (Ibid). Example: Church of England (Gibbs J 594). For Stephen J – it could extend to merely favouring one church over another (610). Dissent: - Murphy J: separation of the clause means that it forbids not only a national church and any preference of one religion over others, but also sponsorship or support of any religion - Problems with this: We shouldn’t compare USA to Aus because even in the USA understanding of the non-establishment clause has changed over time on federation, some US states had established churches and supported religious groups, only in the 50s and 60s did issues arise regarding religion in school TRIAL BY JURY Section 80: The trial on indictment of any offence against any law of the Commonwealth shall be by jury, and every such trial shall be held in the State where the offence was committed, and if the offence was not committed within any State the trial shall be held at such place or places as the Parliament prescribes. INTERPRETATION OF S 80 ‘Section 80 might thus be translated to: There shall be trial by jury in those cases where the law provides that there shall be trial by jury.”’ (George Williams et al, Blackshield &Williams Australian Constitutional Law (Federation Press, 6thed, 2014) [26.78]) Two options: 1. Provision is designed to give power to Parliament to determine when there should be trial by jury (McHugh J in Cheng v The Queen (2000) 203 CLR 248); or 2. Designed as a right of accused to trial by peers, inclusion in criminal process, for serious offences (e.g. Deane J in Kingswell vThe Queen (1985) 159 CLR 264) 93 The High Court has repeatedly held that the application of these words lies wholly within the discretion of the Commonwealth Parliament.’ (B&W) I.e. if the trial is by summary offence, the right doesn’t apply. McHugh, 299: – ‘My hesitation would be increased by the knowledge that in 1988 a substantial majority of the Australian people refused to approve an amendment to s 80. That amendment would have required a jury trial where the person was being tried ‘for an offence, where the accused is liable to imprisonment for more than two years or any form of corporal punishment’.’ Cheatle v The Queen (1993) 177 CLR 541 Issue: whether judge could accept majority verdict (10/12) in SA Held: jury unanimity is an essential element of the ‘trial by jury’ guaranteed by s 80. Reasoning: - The requirement of a unanimous verdict ensures that the representative character and the collective nature of the jury are carried forward into any ultimate verdict’ (552-53) Reflecting beyond reasonable doubt standard Reflecting framer’s intentions. BILL OF RIGHTS The below document provides arguments for and against a State Bill of Rights. It is important to note that some of the arguments below will not apply to a Commonwealth Statute because of the differing level of entrenchment involved in Bills and statutes. NSW PARLIAMENT STANDING COMMITTEE ON LAW AND JUSTICE, A NSW BILL OF RIGHTS (17 OCTOBER 2001) PARLIAMENTARY PAPER, NO 893, CHAPTERS 5 AND 6 ARGUMENTS FOR A NSW BILL OF RIGHTS The committee received 52 submission in support of a NSW Bill of Rights The most important arguments relevant to a NSW statutory Bill are: 1. The educative value of a Bill of Rights in political debates, thereby developing greater understanding of human rights within the community 2. The inadequate protections of human rights for the community, due to gaps in current legislation and the uncertainty of the common law 3. The inadequate protection of minorities in society in the absence of a Bill 4. The international isolation of the development of domestic law in the absence of a Bill of Rights 94 5. A Bill of Rights can facilitate a constructive dialogue between the Judiciary and the Parliament EDUCATIVE VALUE Rights can be more easily accessible - Would express the major rights of a community in a written form in one document - Simplified the process for the general community wishing to understand the rights to which they are entitled - Example: the Qld parliamentary committee produced a booklet entitled Queenslanders' Basic Rights in order to clarify the many sources of law which provide Qld citizens with their rights - The leading proponent of the educative value of a Bill was Professor George Williams, a constitutional lawyer at UNSW o Argued that Bill of Rights consolidates in one document what are seen as the 'core rights' for a society', and by doing so provides the general community with a document they can turn to - Chair of the Law Society's Human Rights Committee also saw a Bill of Rights as not only educational but potentially inspirational, leading to a greater understanding of law generally - Dr Larissa Behrendt of NU used the example of Mabo: o 'after the Mabo case … they all knew about the Mabo case and about native title and what it meant. When these rights actually become more of a reality people will get a better sense of what they entail.' Development of a Human Rights Culture in Political Debate - Professor Williams sees the educative value of a Bill as having the effect of improving tolerance in the community and strengthening the protection of human rights o Argues that a broad based community understanding of human rights would make it less likely that legislation such as mandatory sentencing would be put forward by governments Development of a Human Rights Culture in the Bureaucracy - Under most Bills of Rights overseas, legislation and regulation generally need to comply with provisions in the Bill o Public servants developing new policies or drafting statutes to give effect to political initiatives are required to measure up these proposals against the standards set out in the Bill ▪ Human rights considerations can become as important a consideration as budgetary impacts of new proposals - In a study entitled The Impact of the Human Rights Act: Lessons from Canada and New Zealand o UK academic researchers found that the bureaucracies or both countries had undertaken reviews of all existing legislation and regulations for compliance with relevant human rights standards 95 - A study of Canadian officials in 1992 found that the Charter had completely changed the way in which policy proposals reached cabinet, with the development of a culture of resolving human rights issues prior to proposals becoming legislation INADEQUATE PROTECTIONS IN EXISTING LAWS Current laws provide inadequate protection against human rights abuses - Some highlighted issues overall - Some highlighted issues in relation to protection of minority groups - Some of the examples provided by witnesses of individual instances include: o The overriding of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) in 1998 by Federal Government Amendments to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to give effect to pastoral leases on native title land (the Wik Bill) o The jailing of political activist Albert Langer in 1996 for advocating, contrary to a provision in the Electoral Act 1918 (Cth), that voters put major parties equal last when voting in an election o The passage of legislation by a NSW government which extended the sentence of an individual prisoner, Gregory Kable, after the completion of the sentence given at his trial o The successful defamation action by One Nation Party leader Pauline Hanson which prevented the playing on radio of a song satirising the leader's political views o The removal of the right of an accused to make an unsworn statement in NSW criminal trials; and o The prevention of religious groups from distributing literature within a certain radius of Olympic sites during the Sydney Olympics - Many examples were also given of systemic problems, whereby significant groups in the population were denied basic rights: o The lack of adequate access to water supplier and other infrastructure by remote rural communities o The passage of mandatory sentencing legislation in Western Australia and the Northern Territory which remove judicial discretion to consider the circumstances of the individual offender when sentencing o The lack of simple remedies available to members of the 'stolen generation' o The lack of access by disabled persons to more basic services such as transport and appropriate housing o Inadequate legal aid funding leading to lack of legal representation of the poor and disadvantaged - Other examples were provided of gaps in human rights protections which affected the whole community: o The lack of privacy laws o The lack of laws to ensure adequate compensation for acquisition of private property by the State Government 96 o - The encroachment of legislation affecting longstanding common law rights within the criminal justice system Some of the above are outside the ability of a NSW Bill of Rights to remedy in the absence of a Federal Bill Several different explanations for why current laws provide inadequate protection: o Common law too vulnerable to being overridden by legislation o Inadequate protection to wider populace o Disadvantaged groups with little electoral power had been largely ignored by legislators and decision makers - current laws given them no remedy to this situation Weakness of the common law - Many common-law rights reflect those established under the ICCPR, and even go beyond the ICCPR - However, they are too easily overridden by legislation - 'the only effect of common law rights is residual, covering the gaps not addressed by legislation' - Law Society NSW argues that, under our current system, 'rights' are only what is left after governments have taken away many freedoms - Senior Public Defender John Nicholson QC gave an example of an investigatory body contravening several common-law rights in the process of an investigation - There is also an argument that may protections within the common law are insufficient to meet modern conditions - One of the strongest criticism of the ability of the common law to protect human rights came from a serving judge of the NSW Court of Appeal, NSW Supreme Court, Hon Justice Paul Stein: o He supported those who argue that the common law can be slow to adapt o Highlighted the rights of women as one area where legislation has had to lead the way to remedy deficiencies in the common law o Common law failed to develop in areas such as the right to enter the professions , women's right to control over property in marriage and the existence of an offence of sexual assault in marriage - He also noted that the common law has also acted to deny other rights: o Cases have denied any right to privacy: Victoria Park Racing and Recreational Grounds Club Co Ltd v Taylor ; any right of public meeting for political purposes: Duncan v Jones; any right of protest, apart from petitioning parliament: Campbell v Samuels; any fundamental guarantee of religious freedom and expression: Grace Bible Church v Reedman - The common law also does no provide 'positive rights', rather it operates negatively - Judge Grogan of the NSW District Court highlighted that the common law is opportunistic, needing specific cases to be run for a right to be established. - The development of rights protection in the hands of individual judges, and particularly influenced by the composition of the higher courts o History shows that the availability, scope and application of rights can vary according to changes in the composition of a court o Rights discovered by the judiciary also have little symbolic or educative effect since their existence is not known prospectively and they are not publicised widely 97 Weakness of Statutory Protections - Existing statutes provide some protections - however it as argued by several witnesses that these statutes were often not given enforceable remedies, and that these rights given could be easily taken away - While it could be argued that a statutory Bill of Rights does not appease this problem, you could also argue that statutory Bills acquire status of 'fundamental legislation' so that it becomes politically very difficult to amend, even if it remains possible - 'gaps' in current protections and the unwillingness of governments to address those needs o Particularly in the event of minorities INADEQUATE PROTECTION OF MINORITIES UNDER EXISTING LAW - - Consideration of whether 'economic, social and cultural rights, group rights, and the rights of indigenous people should be included in a Bill of Rights' o While economic, social and cultural rights can be enjoyed by the whole population, they can be particularly disadvantageous to groups One of the principal arguments in favour of a Bill of Rights is that the reliance upon responsible government to protect rights means that 'unpopular' minorities can have their rights ignored When considering the protection of the rights of minorities mot witnesses addressed these in the context of 'group' rights Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of Minorities - Uniting Care of NSW ACT saw economic, social and cultural rights for minorities, of the type covered by the ICESCR, as the most neglected by existing protections o In NSW, anti-discrimination legislation provides some protection for such groups where the violation of their human rights is related to discrimination o This is not clearly enough - Toomelab Report o It has become clear that the rights of workers to associate, to organise and to strike are under threat - BSR commends the NSW government for its recent initiatives to protect and enhance the rights of outworkers in the garment industry - however these have only emerged after a concerted campaign by community and church groups and the unions, in solidarity with the workers themselves - Uniting Care notes that although Australia has ratified the ICESCR the Conventions provisions have not been entrenched into domestic law and receive ad hoc legislative protection at the discretion of various federal and state governments o This puts the judiciary in a difficult position when interpretations based on Australia' international undertakings are made - Mr David Wiseman argued that the ability to enforce economic, social and cultural rights is not present in NSW Human Rights and People with Disabilities 98 - - - Australia is a signatory to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons and the Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons o Aside from these, the major conventions, such as the ICCPR and ICESCR require governments to ensure all citizens enjoy equal rights and opportunities The Disability Council of NSW has argued that existing legislation aimed at protecting the rights of people with a disability fail to fully meet Australia's international obligations Examples of weaknesses in the legislation include: o The Disability Discrimination Act 1992(Cth) and the Disability Services Act 1993 (NSW) ▪ Operate more as funding mechanisms rather than addressing planning needs with the exclusion of sections of the disability community whose needs cannot be met or whose disability is not captured by those laws o The Community Services (Complaints, Reviews and Monitoring) Act 1993 (NSW) ▪ Limits the Community Services Commission to making recommendations: • Within the resources appropriated by Parliament • Not inconsistent with government policy that stipulates how resources should be allocated o The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission has no power to enforce determinations made under the Disability Discrimination Act, resulting in people with a disability having to appeal to the Federal Court for a legally enforceable ruling The Council provided a list of specific examples in which people with a disability have failed to receive adequate protection of their human rights: o Women with disabilities experience abuse and violence at significantly higher rate than their non-disabled counterparts o People with disabilities often life in inappropriate conditions, with reported incidences of abuse, malnutrition and deaths o People with psychiatric disabilities were subjected to experimental forms of treatment resulting in death (The Chelmsford Inquiry) o People with disabilities have unmet needs in relation to supported accommodation and respite care o Women with disabilities escaping violence are denied access to women's refuges The rights of Indigenous Peoples - Many indigenous groups consider the ICCPR, with its focus on individual rights, insufficient protection for their needs, and that at a minimum the rights given under the ICESCR are necessary - The United Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which has yet to reach the status of a formal declaration, stresses the fundamental right to equality for the world's Indigenous people (art 1) and the special protection required if they are to be able to practice their culture (arts 4, 6, 8 9, and 12-14), including their particular association with land (arts 10 and 25) and to exercise their right to self-determination in political, economic and social terms (art 3) - The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination is also important in debates as to the protection of the rights of indigenous peoples o The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) enacted this domestically, however the 199798 Wik debate overrode this with federal legislation 99 - - - - - - Some argued that it should offer a specific protection of indigenous peoples, while others argued that a general provision preventing racial discrimination would be of great benefit to indigenous peoples There is concern following the Hindmarsh Island case surrounding whether or not the federal government can create pass legislation which would adversely protect a particular race, under the proposition that the federal government has the ability to pass laws on the topic of 'people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make such laws'. o Professor Williams also argues that on the basis of Kruger v Cth there is no power in the Constitution to prevent the forcible removal of indigenous children from their families and communities. Prof. Farth Nettheim, founder of the Aboriginal Law Centre at UNSW argued that the Hindmarsh Island Case was very uncertain in regard to the 'races' power o He expressed concern with the way indigenous peoples had been treated during the debate on the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 (Cth) (the Wik legislation) ▪ As a result of this decision, the NSW government has the power to make laws in respect of indigenous peoples in ways that it did not before Dr Larissa Behrendt expressed the concern that a Bill of Rights is necessary for indigenous Australians due to the Wik decision and Kruger o Believes that any right to equality or freedom from discrimination should provide the opportunity to ensure equality of outcomes The NSW Aboriginal Land Council and the NSW branch of the ABTSI Commission both gave strong support o On the basis that it would advance and protect the interests of the people they represent o Specific concern was had with regard to the ability of the future NSW State government introducing a form of mandatory sentencing which would have dire repercussions for the Indigenous community The NSW ABTSIC Commissioner raised a number of examples where the rights of Indigenous people in NSW might have been treated different under a Bill of Rights: o The lack of access by some NSW Aboriginal communities to clean water, functioning sewerage systems or adequate primary medical care o The lack of debate about human rights to clean water during the passage of the Native Vegetation Conservation Act o The lack of consideration of the cultural rights of Indigenous peoples to fish as a human right issue when the Fisheries Management Act Amendments were considered o The lack of control of Aboriginal people in NSW over their sacred sites, and o The lack of implementation of Aboriginal customary law and the lack of indigenous community based justice systems as part of the NSW criminal justice system Gender Inequality - In population terms women are not a minority in NSW, but the representative of the Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association argued that in other respects they are a minority and would benefit from a Bill of Rights, because they are: 100 o - - An economic minority ▪ Consistently underpaid for the word they do ▪ Consistently denied access to services that they might need ▪ Consistently given less job security through structural discrimination Several international conventions address the rights of women aside from those given by virtue of the general rights in the ICCPR and ICESCR o The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women ▪ Particularly important as it forms the basis of the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) Two organisations representing women's interests, the Women’s Electoral Lobby and Women into Politics, gave evidence during the inquiry o Argued that progress over the last 100 years was too slow and too piecemeal o Argued that a Bill of Rights would accelerate gender equality o Representatives of both organisations argued that the under-representation of women in parliaments meant the protection of women’s rights by statute was largely in the hands of men, and that a Bill of Rights could act to ensure accountability INTERNATIONAL ISOLATION OF DOMESTIC LAW - CJ of NSW, Justice Spigelman, argued that without a bill of rights we will be international isolated and the many jurisdictions that have previously provided guidance in cases will not be able to do so anymore because of their use of Bills of Rights o 'Australia, without a Bill of Rights, is now outside the mainstream of legal development in English speaking countries, particularly those msot comparable in the political and legal systems.' o NSW branch of the International Commission of Jurists: ▪ 'Australia has drawn upon and continues to extensively draw on the common law of the United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand. These countries now each have a Bill of Rights, which has and will continue to have a considerable impact on the development of their jurisprudence. If Australia, including the states and territories, omit to enact a Bill of rights then our ability to draw upon the jurisprudence of these countries will become increasingly limited, notwithstanding our foundational values and aspirations remain the same.' FACILITATION OF DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE JUDICIARY AND THE PARLIAMENT - Arguments surround whether human rights are best protected by parliamentary representatives of the judiciary o Members of the parliament are democratically elected but bound to various interests, including party discipline 101 o - - - Members of the judiciary are able to make judgements free from political constraints but are not directly accountable to the community for the outcomes of those decisions Advocates of a Bill believe in parliamentary supremacy o Others seek a model which can effectively strengthen the power of the Judiciary Despite differences in emphasis, advocates for a Bill of Rights generally all agreed that a Bill would change the nature of the relationship between the Judiciary and the Parliament for the better. While it is difficult to encapsulate the different arguments presented, a summary of the overall view is that a Bill of Rights would allow a more constructive dialogue or interaction between the Judiciary and Parliament than currently occurs. There was particular enthusiasm for the way in which the UK Human Rights Act has formalised this dialogue Ms Debeljak, for Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association, argued that the “dialogue” envisaged under the UK Act would not in any way threaten the separation of powers Those who oppose a Bill of Rights frequently cite the politicisation of the Judiciary as one of its undesirable side effects. However some advocates of a Bill argue that instead, the political role of the Judiciary is made transparent and given formal definition. Judges, they argue, have always taken on a limited policymaking role: all a Bill of Rights does is to take public policy making “out of the closet”. The advantage of a Bill is that it can be used to give the Courts and Parliament a means of dialogue over particular statutes instead of the current situation where no formal dialogue exists. Other advocates have argued that the Judiciary under a Bill of Rights are given an extended role to that which they already play, in the protection of rights of minorities o ...there is the belief that there should be an institution in society which can independently and fairly, and without fear of consequences, safeguard against what Lord Scarman called the ‘modern menace of unbridled majority power’. Human rights essentially concern the protection of minority rights from arbitrary erosion or violation by the majority. The Legislature, which relies on majority support, cannot be expected routinely to risk political self-destruction by promulgating minority causes; on the other hand, the courts, who do not rely on any constituency, risk nothing in protecting them. What body can better attenuate the impact of majoritarian expectations when they may unfairly circumscribe minority ones, than a body which does not depend for its survival on popularity with the majority? ...While [judges] may not be accountable to public opinion, they are nonetheless accountable to the public interest for independent decision-making based on discernible principles rooted in integrity. Interpreting justice involves a complex balancing of legal principle and public interest. Performing the task properly may mean controversy and criticism. But better to court controversy than to court irrelevance, and better to court criticism than to court injustice. ARGUMENTS AGAINST A NSW BILL OF RIGHTS 102 The Committee received 28 submissions and 59 letters opposing a NSW Bill of Rights - Five witnesses gave evidence opposing a domestic Bill - The most important arguments against a NSW Bill are based on the change in relationship between the Parliament, the Executive and the Judiciary The major arguments represented to the Committee are: 1. A Bill would increase the power of the Courts at the expense of the Parliament, undermining Parliamentary supremacy and leading to a politicisation of the Judiciary 2. A Bill would increase uncertainty in the law because rights are widely defined, requiring judicial interpretation to give them content 3. There is no consensus as to which rights should be protected 4. Australian Courts will not be isolated from overseas developments in the absence of a local Bill 5. A Bill could lead to an increase in litigation and associated costs 6. A Bill of Rights could be used to intrude upon the activities of private businesses and associations 7. A focus on rights can lead to lack of acceptance of responsibilities Some of the arguments in submissions and evidence against a Bill were primarily based on difficulties with the US Bill of Rights - Any NSW Bill would be much more likely to follow more recent models such as the Canadian, NZ or UK Bills o For that reason, any arguments based on the US Bill have been excluded unless they illustrate a point which could be equally argued for other forms of Bills A BILL UNDERMINES THE ROLES OF BOTH PARLIAMENT AND THE COURTS - - The extent of change of relationship between arms of government depends on the model of the Bill chosen Change will be influenced by whether the Bill is constitutionally entrenched or statutory, the extent to which override powers are given to the Parliament, and the wording of limitation clauses regarding the rights protected within the Bill Support for a Bill is provided by arguing that the rights of minorities will be enforced through the Courts, however opponents of a Bill argue that to protect human rights in this way is undesirable because: o It undermines the supremacy of an elected Parliament in favour of an unelected Judiciary o Decisions can be made by judges with resource allocation implications; these policy decisions are best made by elected representatives rather than unelected judges. Previously political decisions become legal decisions. o The increased power of the Courts under a Bill politicises the Judiciary and the appointment process of judicial officers, undermining the respect for the rule of law in the wider community, and 103 o The best protection of human rights ultimately is respect for these rights by Parliament and the wider community which elects Parliament; this is undermined if the responsibility for protection is given primarily to the Courts. The reduced power of Parliament makes the work of the Executive more difficult, undermining public confidence in the ability of the political process to deliver outcomes. Undermines Parliamentary Supremacy - Justice KR Handley QC of the NSW Court of Appeal: o 'Giving a court the power to declare and enforce human rights in terms of the international conventions would give unelected judges a blank cheque to decide what, in many cases, are really political questions. Their decisions could have an unexpected impact on the State’s budget in ways that would be outside the control of the government. Australia is essentially a free and democratic society which does not need this type of legislation. All these questions should remain the responsibility of the elected government, and be subject to the restraints and constraints of the democratic process' - Chief Judge in Equity of the NSW Supreme Court, the Hon Malcolm McLelland QC: o A Bill of Rights, by transforming social or political questions into legal questions, would require courts to exercise a similar function in cases coming before them and empower them (if the Bill of Rights were entrenched) to retrospectively invalidate Acts of Parliament on social or political grounds. This would both derogate from the proper role and status of Parliament and be harmful to the legal and judicial systems and to the administration of justice. - The NSW Bar Association argued that while an initial Bill could be said to be an act of Parliamentary power, expressing the will of the people as to which rights to protect, the danger was that this eroded the supremacy of future parliaments Judicial Policymaking: legalising Political Decisions - Bill may give the courts a role which is better suited to Parliament o Argue that widely expressed rights require judicial interpretation to give content to those rights but these decisions have policy implications ▪ A Bill of Rights will encourage an expansion of their role - Mr McLelland argued that there has been an exaggeration of the extent to which judges currently make considerations with regards to policy o Judicial process is not suited to determining aspects of policy because: ▪ Courts are not equipped to ascertain facts or conduct any necessary research or investigations into many matters which would be relevant to the balancing process between societal values • Courts are instead reliant on parties to bring evidence ▪ There isn't the same opportunity for community participation and debate in relation to issues before a court - Bret Walker SC, representing the bar Association, argued that the introduction of a Bill would be that judges would be required to make decisions of 'allocative justice' - deciding a fair allocation of resources between people in society 104 Politicisation of the Judiciary - The policy considerations required by judges will lead to a politicisation of the judiciary o If judges are seen to be political, attention is focussed on the values of individual judges which influence these decisions - This would be detrimental to judicial independence - As in Canada, concerns around judicial appointment will arise o Would therefore weaken the administration of justice Democratic Process as Guardian of Human Rights - In relation to the example of the Peoples Republic of China and the former Soviet Union, arguments are made that the best protection of human rights is respect for the rights in Parliament and the wider community which elects Parliament, which is undermined if the responsibility for protection is given primarily to the Courts - Executive in NSW Hon RJ Carr, expressed the argument that the most abusive and oppressive regimes have had extensive bills of rights - in reality a Bill does not naturally lead to the protection of rights - Most arguments surrounded the idea that parliamentary democracy is the ultimate source of protection of human rights A BILL WOULD CREATE UNCERTAINTY - As human rights are meant to be applied unversally, they need to be expressed in broad terms so as not to limit their effect as circumstances and cultural conditions change Supporters argue that limitation clauses attaching to specific rights can prevent the rights becoming too broad - but, these limitations only add another layer of uncertainty Uncertainty is unavoidable in Bill of Rights - Justice Handley from NSW Court of Appeal argues that the vagueness of a Bill will allow the courts to make them into vehicles of the beliefs and aspirations of non-elected judges whilst remaining insulated and isolated from the realities and the checks and balances of the democratic political process - Mr McLelland found it ironic that under the Canadian Charter and the US Bill of Righs vagueness or uncertainty were grounds for invalidating legislation The costs of uncertainty - Mr McLelland provided a detailed examination of the costs and adverse impacts of uncertainty in the legal system; argued that increasing legal uncertainty will: o Increase the difficulty and expense of obtaining legal advice o Reduce the reliability of legal advice o Reduce the predictability of the outcome of litigation o Increase the likelihood, volume, complexity and length of litigation - McLelland argued that a Bill would add to uncertainty because the range of subjects within the reach of a Bill would be extensive, the scope of potential arguments would be too broad, 105 and the public interest in the question of validity of legislation would create an imperative that validity arguments based on human rights be appealed as far as possible o Argues that certainty would be delayed until finally tested in the HC o Argues that considerable financial resources may be required to ensure the legal system meets the increased demands placed upon it by the complexity and unpredictability caused by a Bill - including the need to appoint more judges to deal with an increased work load Uncertainty encourages speculative cases - McLelland argued that one of the worst outcomes of uncertainty in law is the encouraging of speculative litigation: o Cases would go to trial which would otherwise not have reached this stage o Isses are raised and litigated which ultimately turn out to have no significance o Appeals are instuted and pusued which would otherwise not have been brought - McLelland used the example of civil law over the past 25 years where new laws giving courts wide discretionary power led to a huge increase in the volume, complexity and length of proceedings - Paul Latimer, of the Department of Business Law and Taxation at Monash University, argued that a Bill may provide possibility for challenge to business regulation o The Canadian Charter was an example where it is aimed at individuals but has been taken over and enforced by big businesses - showing the risks to be considered when it comes to drafting a NSW Bill Rights can be given unpredictable interpretations - Justice Handley provided two examples where interpretations were given to statements of human rights that 'could have no conceivable relationship to the purpose of the original authors': o Roe v Wade ▪ 14th Amendment of the US Bill was interpreted as providing the right of women to terminate pregnancy - I don't agree with this criticism - I think that this case was correct in its determination on the interpretation of the Amendment as it is not correct in this instance to refer to what the original framers of the Amendment intended for it to achieve - abortion is a progressive area of law which can not be found in many previous decades of interpretation and therefore requires progressive judges to implement alternative methods of interpretation o Osman v UK ▪ European Court found that under art 6 the applicant had a right to have a determination on the merits of the case and was therefore used to overturn the UK immunity given to police from negligence actions - An example was also given by Ms Julie Debljak from the Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association of a tobacco company in Canada using s 2 of the Charter which offers a right to freedom of expression to prevent legislation banning tobacco advertising 106 NO CONSENSUS ON WHICH RIGHTS TO INCLUDE IN A BILL - - - - Many opponents of a Bill argued that the specific rights protected was a crucial issue - feared either that rights which they considered important may not be protected, or that it would be impossible to find consensus in the community generally on what rights should be in o Some argued that the inclusion of social, economic and cultural rights would lead to court usurping the role of governments in allocating resources o Several argued that there was likely to be strong, potentially divisive disagreement as to the validity of those rights finally chosen Prof. Williams argued for the exclusion of rights with a history of very wide interpretation by judges - i.e. the right to due process or right to equality o Also argued against inclusion of rights where there are strong differences, with the right to life being a key example o NSW Council of Churches disagreed with this - argued that rights should be based on moral rather than pragmatic considerations Mr McLelland raised the problem that the values expressed as rights, in a Bill of Rights are rarely exhaustive o The difficulty with the proposal such as that advocated by Prof. Williams is that the values protected as rights in the Bill are likely to prevail over other values which have not been included Major theme from NSW Bar Association is that it was impossible to fully comment on the ultimate public interest in implementing a local Bill of Rights unless the content and expression of the rights within the Bill was known o Only if rights stated were based upon existing or precisely defined new rights the problems of excessive litigation and wide judicial interpretative powers could be avoided o Bret Walker SC drew on the concerns regarding the vagueness of art 10 of the ICCPR to demonstrate the issues of adopting terms of the ICCPR into local Bill A BILL INCREASES LITIGATION - Some argued that the wide nature of the way 'rights' are expressed invites litigation to clarify the meaning and content of those rights Others argued that a Bill provides an alternative avenue to pursue essentially political agendas Also an argument that Bill of Rights litigation can be used as a tactical approach, where for instance those accused of criminal offences raise technicalities as either a delay tactic or to provide new defences CANADIAN AND NZ EXPERIENCE - Evidence was given that the Canadian Charter and the NZ Bill have resulted in significant increases in litigation based upon the Bill 107 o - Before the charter, the average time that a judgment was reserved in the Supreme Court of Canada was four months, after 4 years it was ten months, and in 1985 and 86 there was 33 judgments that were reserved longer than 12 months Some of the findings in a review of the Canada and NZ experience by the Constitution Unit of London University found: o In NZ 90% of cases under the Bill of Rights Act estimated to be in the area of criminal law o In Canada 74% of Charter cases were in the area of criminal law in the first four years of its operation, with a success rate of 31%. Challenges to breathalyser tests featured prominently, making up 11% of Charter cases o 25% of all appeals in the Canadian Supreme Court are still criminal law Charter cases o Challenges based upon procedural aspects such as detention, search or processing of applications had the highest chance of success in Canadian Courts Creation of new areas of litigation - A Bill of Rights has the potential to create specific new litigation 'industries' where previously there was none - Argued that judicial interpretation of s 116 of the Constitution had already lead to protection being given to religious cults to the detriment of the public interest, and under a Bill even greater latitude could be given Using Courts as a Political Forum - A Bill will only be used by those who have failed to persuade elected representatives of the strength of their case as a means of pursuing essentially political causes - In time a Bill could lead to less litigation rather than more as agencies become more mindful of their responsibilities and improved their practices - but Formed Judge the Hon Malcolm McLelland QC did not support this view LACK OF A BILL DOES NOT ISOLATE DOMESTIC COMMON LAW - McLelland made several points to argue that Australia did not risk intellectual isolation: o The various Bills around the world are all different and nearly always the product of significant historical events, causing difficulties in making straight forward applications of international decisions to local contexts o Australia has six States, two Territories and Federal courts which can share development and precedents in progressing the common law o US cases, particularly the State Courts, have always been used by counsel in Australian courts when needing to argue a difficult proposition, despite constitutional differences o Overseas jurisprudence is not always desirable to adapt locally, with cases on the US 14th Amendment being a clear example where even American lawyers find US jurisprudence incomprehensible 108 - McLelland wished to emphasise the differences in jurisprudence between common law countries While Bret Walker agreed that there had been a drift in overseas jurisdictions towards incorporation of human rights standard into the common law, he disagreed that this trend in overseas jurisdictions was disturbing or threatening to the development of local common law o Walker gave a strong defence of the openness and international awareness of the higher courts in Australia, and argued that Australian courts would continue to make independent use of comparative law in the future A BILL FAVOURS RIGHTS INSTEAD OF RESPONSIBILITIES - - - Whether responsibilities as distinct from rights should be included in a Bill of Rights Debate in international circles as to the extent that responsibilities should co-exist when rights are expressed in treaties and conventions o The granting of a right to someone must of necessity involve a responsibility on another person or institution to honour that right Several arguments that one of the disadvantages of a Bill is that they encourage a culture where individual responsibility is discouraged in favour of claiming rights through litigation o Strongly put by NSW Premier the Hon RJ Carr MP ▪ "If a person is burnt by coffee while juggling it and driving a car at the same time, instead of recognising that it is a really stupid thing to do, the person will sue because the coffee was too hot. How much more litigation will we be inviting by a Bill of Rights?" Submissions from individual citizens were expressed in similar words, concerned that responsibilities should be given more emphasis by governments rather than considering a Bill of Rights A BILL COULD LEAD TO HARMFUL INTRUSIONS INTO PRIVATE ORGANISATIONS - - Circumstances in which a Bill of Rights should be beinding on individuals as distinct from binding the arms of governments or bodies performing a public function NSW Council of Churches said that churches could be the subject of litigation under a Bill of Rights Similar issues were also explored from the Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association, representatives of the Women's Electoral Lobby (regarding the potential for actions against clothing restrictions imposed on women by a conservative ethnic community) and with Commissioners from the NSW Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (regarding private corporations infringing rights of indigenous peoples) Dilemma is that a Bill of Rights which does not bind private or non-government sectors only provides partial protection of human rights in modern society o Conversely, to extend the coverage of a Bill has uncertain and potentially divisive outcomes 109 IMPLIED RIGHTS AND F REEDOMS Section 7: The Senate Senate shall be composed of senators for each State, directly chosen by the people of the State, voting, until the parliament otherwise provides, as one electorate… Section 24: Constitution of House of Representatives The House of Representatives shall be composed of members directly chosen by the people of the Commonwealth… Section 41: Right of Electors of States No adult person who has or acquires a right to vote at elections for the more numerous House of the Parliament of a State shall, while the right continues, be prevented by any law of the Commonwealth from voting at elections for either House of the Parliament of the Commonwealth. Section 128: Mode of Altering the Constitution [This provision provides an express manner in which the Constitution must be amended, including the proportion of society etc. The above provisions entrench the notions of representative and responsible government into our Constitution upon which the implied freedoms have been established. The implied freedoms that will be explained below essentially exist as a manifestation of responsible and representative government on the argument that the systems cannot continue to exist without the implication of these rights and freedoms. IMPLIED RIGHT TO VOTE On the basis of a textual reading of the above provisions, which directly provide responsibilities and rights to citizens in relation to voting members of government, the Court has implied a right to vote into the Constitution. Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106 - Concept of representative government signifies government by the people through their representatives. This denotes sovereign power, which resides in the people and exercised by representatives (137). 110 Cth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) - S 93: Must be 18 years of age and an Australian citizen. S 245(1): It shall be the duty of every elector to vote at each election. McGinty v WA (1996) 186 CLR 140. - Toohey J, 201: according to today’s standards, a system which denied universal adult franchise would fall short of a basic requirement of representative democracy’. - Gaudron J, 221-2: can’t deny suffrage to certain categories of people e.g. minorities. LIMITATIONS ON THE RIGHT TO VOTE Roach v Electoral Commissioner (2007) 233 CLR 162 Facts: - Concerned new laws preventing prisoners from voting. Previously, prisoners couldn’t vote if serving a sentence of 3 years or more. Issue: Did ss 7 and 24 imply a constitutional protection of the right to vote? Decision and reasoning: - - - ‘Choice by the people’ = universal adult suffrage arising from historical circumstances and legislative history Parliament can restrict but these must: ‘Constitute a substantial reason for exclusion’; must be a ‘rational connection b/w ground for exclusion and class of person (Gleeson CJ 173-174). ‘Be reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve an end which is consistent/compatible with maintenance of constitutionally prescribed system of rep gov’ (Gummow, Kirby, Crennan 199). Disenfranchising prisoners was not a suitable punishment for their offences this would present a federalism problem i.e. if you commit a state crime, there would be Cth consequences Effects of law may be unfair because: o Locality/socio-economic conditions may encourage imprisonment e.g. if fines/community services/home detention unavailable o There are short term sentences o Thus, law not reasonably appropriate and adapted, previous law more appropriate (only disenfranchised prisoners serving 3+ yr sentences). Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 243 CLR 1 Facts: - Concerned laws enacted in 2007 that limited the time period for enrollment between calling elections and submitting writs. 111 Issue: Is there a minimum content required by aspect that government is ‘directly chosen by the people’? (Remember Roach: law must satisfy requirements of a system of representative government (more than simply direct popular choice).) Reasoning and decision: - - French CJ o SS 8 and 30 implied that right to vote continues to expand in its democratic content. Right can be adjusted but not diminished (18). o There is no ‘minimum requirement’ but the impugned laws must be proportionate to constitutional mandate of representative government. o Here, the law aimed to avert fraud (by maintaining an up to date roll) and remind electors of responsibility for enrolment thus furthered constitutional mandate of representative democracy ▪ These were legitimate aims but with disproportionate means ▪ No existing fraud problems, existing measures to ensure up to date roll were sufficient, period for enrolment had been sufficient for the past 50 years o Thus, closing window for enrolment was not reasonable appropriate and adapted to achieve the goal of averting fraud and reminding electors of responsibility for enrolment. Criticism by Hayne J: o Inability to vote arose from person’s own failure to act in accordance with reasonable legal requirements o Thus, laws were reasonable and appropriate and adapted as a means to achieve representative government Criticism by Anne Twomey: - ‘By upholding previous law allowing a grace period, the HC has constitutionalized what parliament already said in its law. This allows P to give content to a constitutional right to vote, thus gives P potential to alter the Constitution.’ STRUCTU RALISM Structuralism refers to the notion of using the Constitution’s structure to imply rights and freedoms available to the people. It considers the implications arising from the Structure of the Constitution itself. This is important because, on the words of the Constitution, we don’t have guaranteed or explicit rights, however we do have rights which are implied into the text on the basis that the structure of the text cannot be satisfied or maintained without these rights. Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1992) 136 - It is difficult to establish a foundation for the implication of general guarantees of fundamental rights and freedoms Doing so would be contrary to framers intention that BOR unnecessary 112 - Mason 135: can imply rights if logically or practically necessary for preservation of the integrity of the structure (ambiguous statement) Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997) 189 CLR 520 at 566–567 - Implied freedoms are not free standing they don’t exist as a matter of judicial wisdom Constitution gives effect to the institution of representative government only to the extent that text and structure of the Constitution establish it. The relevant question is not, ‘what is required by representative or responsible government?” The question is: What do the terms and structure of the Constitution prohibit, authorize or require? Theophanous v Herald & Weekly Times Ltd (1994) 182 CLR 104, 198: - Since Engineers, Cts have said Const can’t be interpreted using political principles and theories that aren’t supported by text. But you can use theories of federalism, politics and economics when there are grounds to conclude that the provision’s meaning was intended to be understood by reference to such a theory. J Goldsworthy, Constitutional Implications and Freedom of Political Speech: A Reply to Stephen Donaghue (1997) 23 Monash University Law Review 362, 371 To find implications of rights and freedoms, it is necessary to determine: 1. Founders intended representative government, 2. Founders determined that this required those parts of the text not including the implied freedom, 3. They were wrong and supporting rep gov requires the implied freedom, 4. Thus, implied freedom exists. However, he rejects institutional efficacy arguments: being that rights can be implied if they assist institutional structure (372). J Kirk, Constitutional Implications (I): Nature, Legitimacy, Classification, Examples (2000) 24 Melbourne University Law Review 645 at 654 When considering implied rights/freedoms, consider: - - Strength of positive imperatives supporting implication (i.e. framers intentions; what is reasonable to see as communicated even if not considered; institutional efficacy) o NB: institutional efficacy – we can imply rights if they assist institutional structure Textual manifestation and guidance Whether implication can be precisely defined Consequences Judicial administrability Political centrality of the issues 113 A Stone, The Limits of Constitutional Text and Structure Revisited (2005) 28 University of New South Wales Law Journal 842 Text and structure don’t give enough content to adjudicate actual cases. Representative and responsible government are concepts determined by the existence of ss 7, 24 and 128 of the Constitution. They are therefore concepts which are not expressly referred to by the Constitution, however remain necessary for the functioning of Australian government. The implied right to political communication is established as an extension to protecting this aspect of representative government. Prior to Lange, there was no strict test in relation to determining whether legislation imposes on the implied right of political communication – the prior cases were determined on a 3:3:1 basis. IMPLIED FREEDOM OF POLITICAL C OMMU NICATION Upon the decision of Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the HC affirmed the existence of the implied freedom of political communication. This implied freedom exists as a limition on Commonwealth and State action in the exercise of their powers. While the freedom is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, it is derived from the text and structure of the Constitution (i.e. on the basis of textualist and structuralist understandings). Sections 7, 24, 41 and 128 set out our rights to choose our representatives, and the IFOPC is imposed to restrict the legislative powers which support this representative and responsible system of government. Lange v ABC (1997) 198 CLR 520 Facts: - NZ Prime Minister sued ABC for defamation ABC tried to argue a Constitutional defence to defamation, being freedom of political communication and also a common law defence of qualified privilege Issue: whether, and how, the implied freedom of political communication exists in our constitution Held: Yes – there is an implied freedom of political communication Reasoning: - - The necessary implication arises from the text and structure, notably the notion of representative democracy o Specifically: ss 7, 24 and 128 What do the terms and structure of the Constitution prohibit, authorise or require? o System of representative government means there is a freedom concerning governmental or political matters o This enables people to exercise free and informed choice as electors 114 o o - This form of speech is protected by text and structure of the Constitution For example, legislative power can’t be used to deny access to information on political matters in Australia people necessarily must have access to political and governmental information The qualities of this freedom: o It is not a personal right it is a negative limitation on governmental power o Only concern is whether government activities burden the responsible and representative government o Also rejected the notion that the right only exists during election time determined that discussions in politics and the fundamental debates surrounding politics are a continual process and are ongoing therefore the right exists irrespective of whether it is election time Test established under Lange: (as first proposed by Cunliffe) Limb 1: Does the law effectively burden the freedom of political communication in its terms, operation or effect? Limb 2: If so, is the law reasonable appropriate and adapted to serve a legitimate end in a manner of which is compatible with maintaining the system of government prescribed by the Constitution? If the answer is yes to the first question, but no to the second the law is invalid - - In ACTV for example, the Court held that a law seriously impeding discussion during the course of a federal election was invalid because there were other less drastic means by which the objectives of the law could be achieved. If it is necessary, they must be developed to ensure that the protection given to a personal reputation does not unnecessarily or unreasonably impair the freedom of communication about government and political matters which the Constitution requires. Coleman v Power (2004) 220 CLR 1 Facts: - Student protesting against ‘corrupt police’ and gave a pamphlet to Power saying that he was corrupt Charged under QLD legislation which prevented ‘threatening, abusive or insulting words’ in public Issue: What are ‘threatening, abusive, or insulting words’? Held: Applied the principle of legality to determine that ‘threatening, abusive, or insulting words’ were those that intended to or would likely cause violence. Reasoning: - McHugh J: o The real issue is whether the burden imposed on communication was reasonably appropriate and adapted to achieving an end, the fulfilment of which is compatiable 115 - - with the system of representative and responsible government prescribed by the Constitution pursuant to Lange o In determining whether a law is invalid because it is inconsistent with freedom of political communication, it is not a question of giving special weight in aprituclar circumstances to that freedom – nor is it a question of balancing a legislative or execituve end or purpose against that freedom freedom of communication always trumps federal, state and territory laws where they conflict with the freedom ▪ The question is: whether the federal, State or Territorial power is so framed that it impairs or tends to impair the effective operatio of the Constitutional system of representative and responsible government by impermissibly burdening communication on political or governmental matters Effectively this case amended the second limb to say: 1. Is the law reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve a legitimate end in a manner which is compatible with the maintenance of the constitutionally prescribed system of government? Also established that the first point of call is to determine whether the legislation can be read down in line with the Principle of Legality o This means that the words of the statute must be read down in a way which is consistent with the implied freedom of communication o If it is not possible to read down the legislation in a way that does not curtail the IFOPC, you must then turn to the Lange limbs Unions NSW v NSW (2013) 304 ALR 266 Facts: - - Election Funding, Expenditure and Disclosures Act 1981 (NSW) included: o S 96D: prohibited accepting political donations from anyone other than an enrolled elector (the ‘donor prohibition’), and o S 95G(6): expenditure of an ‘affiliated organisation’ was aggregated with expenditure of the party (the ‘aggregate requirement’) Under this, the Unions NSW would be prohibited from donating money and the expenditure of some of its members could be aggregated with the party (it was affiliated with the Labor Party NSW) Issues: 1. Was there a burden on communication protected by the federal constitution? 2. Did the donor prohibition burden the IFOPC in its terms, operation or effect? a. Including – establishing donating is a form of political communication, or else connected to it? 3. If so, was the law for a purpose that is compatible with the constitutionally prescribed system of representative government (a ‘legitimate end’) 4. Did the aggregate requirement burden the IFOPC in its terms, operation or effect? 5. If so, was the law for a purpose that is compatible with the constitutionally prescribed system of a representative government? 116 Issue 1: - Held: yes it did o Pointed to the Constitution s 96 – funding from the Commonwealth – the use of executive and legislative arrangements, COAG and national political parties Issues 2 and 4: - Majority: both amendments impermissibly burdened the implied freedom o Donations themselves were not understood to be PC – what was burdened was that the political parties, through restriction of funds, would be burdened in their efforts relating to PC o Emphasised, from Lange, ‘the FOPC is limited to what is necessary for the effective operation of the system of government provided by the Constitution Issues 3 and 5: - - The second limb of Lange asks: o Is the provision reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve a legitimate end in a manner which is compatible with the maintenance of the Constitutionally prescribed system of government? Joint judgment held that this first requires: o The identifying of the purpose of the provision in question: ▪ The legitimate purpose must be consistent with the requirement of representative government ▪ The provision must be rationally connected to that purpose o The above must be satisfied before turning to the reasonable proportionality part of the second limb Tajjour v NSW [2014] HCA 35 (8 October 2014) Essentially this case was in relation to whether an act relating to prevention of consorting was reasonably adapted to its purpose, or whether it impermissibly burdened communication. Was determined that it was reasonably appropriate as there were no other alternatives which could provide less of a burden on the freedom. Therefore, while it did burden the freedom, it was reasonably adapted to a legitimate purpose. Judicial Opinions: - French CJ: o Offered a non-exhaustive list of cases where the implied freedom would be burdened: ▪ A law which expressly restricts or prohibits communication on ogvenmental or political matters ▪ A law which restricts or prohibits communication by reference to characteristics of its content which may or may not involve governmental or political matters ▪ A law which restricts or prohibits communications by reference to a mode of communication, without regard to the content of the communication 117 ▪ - - A law which restricts or prohibits an activity, which is not defined by reference to communication on governmental or political matters, where the law may operate in some circumstances to restrict or prohibit such communication o Determined that this case fell under the fourth category o While the burden was imposed for a legitimate end – it was not reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve the end Hayne J: o Satisfied both limbs o Believed the available alternatives would not be able to achieve the aim of the law to the same extent – nor would they be practicable o Further held the burden was not ‘undue’ consorting has a long history in Australia – while this is not conclusive, it does have relevance Keane J: o Focused on statutory construction o Considered that it did not proscribe communication by or between any persons on political and governmental matters because this does not, of itself, amount to consorting, because: ▪ The history of interpretation of consorting ▪ Principle of Legality o Essentially Keane J determined that they could still have a freedom of political communication without being found to have consorted in these instances ▪ PC does not equal consorting McCloy v NSW [2015] HCA 34 (7 October 2015) Facts: - - - Concerned amendments to Election Funding, Expenditure, and Disclosures Act 1981 (NSW) o Capped political donations from any person o Prohibited donations from a ‘prohibited donor’ – included property developers P argued this was a burden on FOPC: o Limited access to funds for political candidate o Using money to secure access to a politician was an aspect of the FOPC P argued these burdens were unconstitutional – limit to FOPC not appropriate and adapted to a legitimate object Held: both burdens constitutional pursued a legitimate object in a reasonably appropriate and adapted manner Decision and Reasoning: 1. Legitimacy of the donation cap a. Rationally connected to a legitimate object: preventing corruption and perceived corruption – clientelism, and b. Appropriate and adapted (proportionate) means of pursuing this object: no compelling alternative to do so, burden was incidental. 2. Legitimacy of ‘prohibited donors’ in the context of FOPC a. This raised two questions: 118 i. How is the implied freedom understood 1. Argument: Ps argued that own freedom was at stake- using money to secure access to politician was part of the implied freedom 2. Majority: the burden only restricted funds available to political parties/candidates to meet costs of political communication. Giving money isn’t a form of political speech. FOPC not a personal right a. Significance: you can restrict liberty if it supports representative and responsible government. 3. Dissent: Nettle J [241] ‘Prohibited donors’ not a justifiable limit on FOPC. a. Prevented giving money and giving ideas (political speech). b. No obvious alternative. ii. What is the appropriate inquiry when addressing the relationship between object of law and means adopted by legislature? (see below) Test imposed by McCloy Question 1: Does the law effectively burden the freedom in its terms, operation or effect? (Lange). Question 2: Does the law pursue a legitimate object and does it adopt legitimate means? - If object or means impinges on functioning of rep government = not legitimate o E.g. prohibition of religious speech not legitimate. It is permissible to target a particular problem, don’t’ have to target every single problem to be legit. Question 3: Is the law reasonably appropriate and adapted to advance that legitimate object? (‘Proportionality’) - Must be: 1. Suitable there must be a rational connection between the purpose of the provision and the means to achieve it (Example: McCloy – rational connection; Unions NSW – no rational connection) 2. Necessary there must be an obvious and compelling alternative that is less restrictive on the FOPC a. Tajjour – we must ask if the law can be re-done in a manner less restrictive on FOPC 3. Adequate in its balance Court compares positive effect of realizing the law’s proper purpose with negative effects arising from limiting the constitutional freedom a. i.e. does the positive/negative effect outweigh the other? Criticisms of the proportionality analysis: Gaegler J: - This case didn’t call for considering a wholesale adoption of proportionality analysis Uniform approach may not be adequate 119 - The approach is too monochromatic (one size fits all): we should be more concerned with nature of the burden For example, a law prohibiting criticism of government is more concerning than a law on consorting (indirect effect on freedom) Current legislation to consider - NSW prohibit locking yourself to mining equipment fine up to $5,500, lower fine for other forms of trespassing pointing towards curtailing expression of certain protestors New VIC Act prohibit: distribution of material causing distress to those accessing abortion clinics; impeding access to clinics; intentionally recording people leaving/entering New Commonwealth Act makes it an offence for entrusted persons to disclose info regarding state of detention centres TEST TO BE APPLIED I N EXAM 1. Is the legislation one with respect to a head of power? 2. Interpret provisions using Principle of Legality (Coleman) a. Is it possible to read down the legislation in a way that does not impose a burden? b. If it is possible legislation will be read down and no burden on FOPC will be enforced c. If it is not possible move on to Lange limbs 3. Does the law effectively burden the freedom of political communication in its terms, operation or effect? (Lange). 4. If so, is the law reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve a legitimate end in a manner compatible with maintaining the system of government prescribed by the Constitution? (Lange) a. Does the law pursue a legitimate object and does it adopt legitimate means? (McCloy) i. If object or means impinges on functioning of rep government = not legitimate E.g. prohibition of religious speech not legitimate ii. It is permissible to target a particular problem, don’t’ have to target every single problem to be legit b. Is the law reasonably appropriate and adapted to advance that legitimate object? (‘Proportionality’) (McCloy) i. Suitable there must be a rational connection between the purpose of the provision and the means to achieve it (Example: McCloy – rational connection; Unions NSW – no rational connection) ii. Necessary there must be an obvious and compelling alternative that is less restrictive on the FOPC 1. Example: Tajjour – we must ask if the law can be re-done in a manner less restrictive on FOPC iii. Adequate in its balance Court compares positive effect of realizing the law’s proper purpose with negative effects arising from limiting the constitutional freedom 1. Does the positive/negative effect outweigh the other? 120 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES O F AUSTRALIA In the history of the progression of indigenous peoples in Australia, there are two primary cases which affected their rights and recognition. MABO AND SOVEREIGNTY The major questions surrounding the issue of Indigenous sovereignty are: 1. Was Australia settled, conquered, or ceded? 2. How does the answer to the above effect the Indigenous peoples? Was Australia settled, conquered or ceded? - If conquered or ceded: pre-exsting law continues unless abrogated by inconsistent Act of the new sovereign If settled: both common law and statute of England immediately in force - This was considered to be the position in Australia Relevance of the Indigenous Peoples - Taken not to have effective possession given perceived absence of cultivation, property ownership James Cook referred to Aboriginals as ‘wild beasts in search of food’ Ignored despite estimated 500,000+ people Preamble to the Constitution doesn’t make reference to Indigenous Australians or taking of their land Until 1967, Aboriginals not counted in referendums (s 127) Aboriginals expressly excluded from franchise until 1962 on the basis of poor intelligence Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 Facts: - Meriam people claimed native title to land in Murray Islands not fully abrogated by a sovereign Act Issues: 1. Was Australia conquered, ceded, or settled? a. What legal difference does this make? b. Where do these doctrines come from? 2. How does Brennan J resolve the discrepancy between the doctrinal position and the historical error? 3. How is the Mabo decision limited? 121 a. How do Mabo and subsequent cases like Yorta Yorta understand sovereignty? Held: Common law recognised continuing native tile after British acquisition of sovereignty. Native title could be extinguished by contrary Act Reasoning/Discussion: 1. Was Australia conquered, ceded or settled? What legal difference does this make? Where do these doctrines come from? - Deane and Gaudron JJ: - Settled under common law because no pre-existing legal sovereign, no pre-settlement property regime - This classification is problematic because laws/customs were long standing and recognised by other tribes. Called a ‘normative system’ in subsequent cases of Yorta Yorta - Brennan J: - Enlarged notion of terra nullius reconciled this position: land inhibited but ‘unsettled’ given perception of low intelligence i. Gives rise to tension: ‘settled’ but inhabited 2. How does Brennan J resolve the discrepancy between the doctrinal position and the historical error? - We should use rules that would apply if colony was conquered so that existing rights can continue in absence of an inconsistent Act - Australia still settled, so existing rights/interests would be confined to rights and interests in land only - Why? - Move beyond age of racial discrimination 3. How is the Mabo decision limited? How do Mabo and subsequent cases like Yorta Yorta understand sovereignty? - Doesn’t overturn ‘settlement’ because: - Native title is a common law doctrine - Disputing settlement would raise questions of pre-existing sovereignty - If Court said Australia was conquered: - Its own position would be questionable/challenged (as a product of the sovereign) - Legal institutions, law, self-governance would all be challenged - Rather than overturning ‘settlement’ it aligns settlement with being conquered or ceded for the limited purpose of recognising NT in land DIFFICULTIES IN ESTABLISHING NATIVE TITLE In order for Indigenous peoples to establish the existence of native title, it is necessary to prove the existence of: - Boundaries Proof of membership of group/clan 122 - Traditional connection with land substantially maintained in conformity with traditional law and customs Relatively uninterrupted observance (Yorta Yorta) These are all difficult given changes in history since colonialism. Coe v Commonwealth (No 2) (1993) 118 ALR 193 - Aboriginals do not have distinct political societies Don’t have legislative, executive or judicial organs by which sovereignty might be exercised Here, Court is pushing back against the idea that a normative system of law extends beyond Native Title Walker v NSW (1994) 182 CLR 45 - There is not an ongoing customary criminal law in the same sense as Native Title This is because all persons must be equal before the law A construction otherwise would mean different sanctions for different people for same offence Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 - Rejected pluralistic notion of sovereignty Assertion of sovereignty by Britain = no parallel law of Aboriginals Recognition must be consistent with the current legal order, and Native Title may be recognised because Native Title is a common law principle ONGOING INFLUENCES - UN declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples adopted by Rudd government in 2009 Apology to Australian Aboriginals in 2008 NT Intervention Closing the Gaps: attempt to close gaps in life expectancy, education access, reading and numeracy, employment – but ineffective 123 THE RACE POWER, INDI GENOUS RECOGNITION AND CONSTITUTIONAL C HANGE THE RACE POWER Section 51(xxvi): The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to… The people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws. Kartinyeri v Commonwealth (1998) 195 CLR 337 Facts: - - Minister could make declarations to preserve and protect Aboriginal areas under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth) Commonwealth then passed another Act – Hindmarsh Bridge Act 1995 – preventing Minister from nominating a person to make a report into Aboriginal areas. These reports were a prerequisite to issuing declarations on protection Thus, Act removed possible protection for Aboriginal areas around the bridge Plaintiff’s Arguments: 1. Race power didn’t allow law that distinguished and discriminated between members of a racial group 2. Race power only authorises laws for the benefit of a people, race or alternatively, the benefit of Aboriginal peoples Held: The law is one with respect to the race power – you can therefore repeal the law under the same head of power because if you couldn’t, it would be akin to constitutionalising and entrenching it. Issues & Answers: 1. - Do amendments have to benefit a race? No, see discussions in 2 and 3 Amendments in 1967 didn’t amount to requiring a benefit (Gaudron J) Specialness = can benefit or disadvantage (Gummow and Hayne JJ) 2. What was the relevance of the 1967 amendment? - In 1967, Constitution was changed, allowing Commonwealth to make laws with respect to Aboriginals - Plaintiff argued that this conferred intention to make laws benefiting Aboriginals - Gaudron J: - Amendment didn’t change language and syntax of power - Mere change didn’t curtail the power rather than amended it 124 - - If the section authorised laws that didn’t benefit a race, the 1967 referendum didn’t alter that position - Gummow and Hayne JJ agreed - Emphasis on natural reading of text (Engineers) Kirby (dissent): - Race power only permits beneficial laws - Constitutional authority grounded in popular sovereignty, and referendum in 1967 showed intention to benefit Aboriginals and address history of discrimination - Appealing to convention debates and popular sovereignty 3. The meaning of ‘for whom it is deemed necessary’ - Gaudron J (ratio): - Necessity means: i. Material on which Parliament might reasonably form judgement that there is a difference pertaining to that race, and ii. Law must be reasonably capable of being viewed as appropriate and adapted to the difference - E.g. if Arabic speakers are having difficulty integrating in community due to English difficulties (that is the difference) laws providing they must attend Arabic only schools not appropriate and adapted because manifestly furthers disadvantage and not a rational response to difference - Thus held: Bridge Act valid because only a partial repeal of Heritage Act, which was itself a valid law responding in an appropriate and adapted manner to an established difference. - Gummow and Hayne JJ: - Deciding is a Parliamentary judgement not Court - But, if Parliament manifestly abusing race power – Court might deem it necessary 4. To make ‘special laws’ - Specialness = operates differently in respect to those people - Thus can benefit or disadvantage - Can’t read constitutional power down in light of potential abuse (flashback to Engineers) Dissent: - Kirby J: ‘for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws’ - ‘For’ is ambiguous: it could mean for benefit or in respect of i. the words ‘in respect of’ are found elsewhere in the text, so if the framers just wanted these words – they would be there ii. surely we should read in light of intention to overcome racial discrimination - Act merely aims to build bridge, no connection to the people 125 THE RELEVANCE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Gummow and Hayne JJ (majority): - Ordinary statute (not Constitution) can be interpreted in light of international law But the Constitution cannot - It is a plenary power and supreme i. Plenary: this means that the Parliament can make laws as long as they are within the scope of its power - If we read Constitution in light of international law, this would constrain what Parliament can do under the Constitution - Similar to Al Kateb – per McHugh J – what does international law have to do with our 1901 Constitution? Not much! Kirby J: - You can appeal to international law to uphold fundamental rights when the Constitution is ambiguous Here, ‘for’ is ambiguous INDIGENOUS RECOGNITION AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE YOUMEUNITY REPORT 2012 Recommended that Australian should vote in a referendum to: - - - Remove s 25 – which, for Commonwealth elections, discounts persons of any race disqualified from voting by a state law Remove s 51(xxvi) – which can be used to pass laws that discriminate against people based on their race Insert a new s 51A – to recognise ATSI peoples and to preserve the Australian Government’s ability to pass laws for ATSI peoples, ‘acknowledging the need to secure their advancement’ i. New race power to secure advancement, fitting nicely with intentions of 1967 amendments Insert s 116A – banning racial discrimination by government (while permitting positive discrimination) i. Is this appropriate? Concern for mini Bill of Rights Insert s 127A – recognising ATSI languages were this country’s first languages, while confirming that English is Australia’s national language 126 JOINT SELECTION COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL RECOGNITION FOR ATSI PEOPLES, PARLIAMENT OF AUSTRALIA, FINAL REPORT (2015) - Three proposals to replace race power – within Constitutional text (not preamble) as preamble can’t be used to interpret Rejecting language provision as they don’t want constitutionalising of the English language PUBLIC LAW AND POLICY RESEARCH UNIT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE - - Insert s 60A o Power to make laws…with respect to Aboriginal and TSI people o A law of the commonwealth, State or Territory, must not discriminate adversely against ATSI peoples Arguably, ATSI communities have said that it is fundamental to have SOME provision to prevent adverse legislation - so satisfies this, and also extends it out to State and Territory legislation - which arguably mirrors better the experience of indigenous persons ebcause it has typically been State laws which provide a problem of discrimination POSSIBILITY OF A TREATY? - Constitutional recognition a distraction? An incorporation inconsistent with indigenous sovereignty? - State-based? Commonwealth? - What is meant by sovereignty? - Treaty-making: pre-existing power; ceding authority; conquest - Mutually exclusive ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART (MAY 2017) - Summit of significant number of aboriginal elders - Organised by the referendum council o A body set up by the PM and leader of opposition to further discussion around constitutional discussion - Set up by parliament and included discussion with indigenous leaders - culminated in Uluru over three days - They've come up with a statement rejecting that the constitution should be amended purely for a recognition statement - classic example was the one put forward by Howard when he was PM - or the preamble statements put forward in the proposals for s 51 - this is purely symbolism and doesn't go far enough 127 Proposals: - Put on the table the notion of 'the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution - deputy Prime Minister rejected this by saying you can't have a third house of Parliament but he was criticised for this because it was not reflecting the discussion that took place at Uluru o - Also proposing 'a Makaratta Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations - specifically proposing a body that would be advancing treaty making. o - Would be proposing a body that would be advising the Commonwealth parliament particularly around laws and how they impact ATSI - bodies like this have been put in before and discarded - Body advising commonwealth parliament - requires constitutional amendment to entrench it Already begun in some states - first treaty between WA and Noongar people The Makaratta Commission proposed above…truth-telling about our history o This is the truth and reconciliation part ▪ o This has taken place in countries such as SA after Apartheid and Rwanda after the genocide Allows people to come forward and tell stories of acts of genocide or violence in a manner that is attempting to engage in a process of truth telling and arguably forgiveness Do the proposals above get rid of the need to amend s 51? Because if s 51 remains in power, there is still a constitutional power to make laws for a particular race whether this is to their detriment or not (as a result of Kartinyeri). There is also still a s 25 which can omit them from the voting process - Whether these things run parallel to each other or whether one should be focused on over the other o i.e. is amending s 51 a priority, or are the proposals laid down in the Uluru Statement a priority; or should they all be done because it is all equally necessary? Criticisms/thoughts on the Uluru Statement - One of the criticisms from Barnaby Joyce - we propose all these things and then the immediate reaction is to say 'no that's not what we want' - They link the overrepresentation of indigenous youth in incarceration with not having a sense of autonomy over their own people - that there has been a cultural fracturing in the indigenous community Questions: If a body was to advise parliament, would it be de jure, or consultative? Who would be involved? 128 EXAM HINTS HYPOTHETICAL PROBLEM TOPICS - Corporations power Interstate Trade and Commerce Power Inconsistency Judicial Power ESSAY TOPICS - - - - S 128 (indigenous peoples, s 51 (xxxi)) o Should there be constitutional recognition of indigenous peoples/which of the proposals is the better option and why? o Should we get rid of the Race Power o Something about Kartinyeri Freedom of Political Communication o Was Lange corectly decided o Is there in fact an implied freedom of political communication in the Constitution Federalism o WorkChoices o To what extent should the federal structure be recognised in interpreting the constitution Human Rights Act o Should we have 129