Milton's Sonnet XIX: Stasis and Interpretation

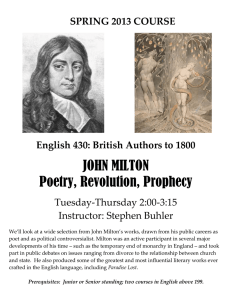

advertisement

zyx “TheyAlso Perform the Duties of a Servant Who Only Remain Erect on Their Feet in a Specified Place in Readiness to Receive Orders”: The Dynamics of Stasis in Sonnet XIX (“When I Consider How My Light is Spent.”) Carol Barton zyx zyxwvu zyxwvutsr Written at some point subsequent to Milton’s Davidic conquest of the Goliath Salmasius (and after the full personal price of that public victory had been exacted), Sonnet XIX is a curious poem, full of an irony, doubt, and yearning that are only intensified in their reception by the reader’s presumptive anticipation of lament. The opening lines “When I consider how my light is spent, / Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide” after all reflect the tragic recognition of an accomplishedvisionary that the eyesight on which his service to man and God has depended throughout his lifetime is now no longer his to enjoy, leaving “that one Talent, which is death to hide, / Lodg’d with [him] useless” before his mission on earth has been achieved. No matter how much his Soul may be nonetheless ”more bent / To serve therewith [his] Maker, and present / [His] true account,” it is virtually impossible within the context of the poem for the reader not to join with the poet in mourning a loss that makes him unable to engage in “daylabor” of the kind he has habitually performed for God and England during the preceding forty-four years; and we wonder, as he does, what it is that a blind author can be expected to accomplish in a world without typewriters or Braille. The reader reacts to his dilemma as Milton himself must have done (at least at the onset of his blindness), with bewildered disappointment that God could so ill serve someone who had served his Lord so well, and bereave him of the enjoyment of that glory he had worked with such diligence to achieve, just at the moment that the laurel wreath for his prose conquest of Salmasius was in his grasp. Certainly, we expect the answer to the question “Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?”to be “Of course not!”, and are as perplexed as Milton is by the thought that God would bless him with a talent of such magnitude at one cosmic moment, then deprive him entirely of the ability to make use of it in the next. Twenty-twenty hindsight aside, one cannot choose but see Milton at this juncture as with the poet’s help the reader envisions the mill-slave Samson at Gaza, that is, defeated, diminished, helpless, and blind among his enemies,’ resigned by force to the end of his productive life, and abandoned by all of those who should succor him-“from what highth fall’n’’to what depth of despair fate has plunged him, and after all, hasn’t he given enough? Juxtaposed to the bustling activity of the “thousands [who] at [God’s] bidding speed / And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest,” and amplified by the reproof articulated by Milton’s “patience”that “God doth not need / Either man’s work or [God‘s] own gifts” in recompense for His benevolence to humankind, the problem of how the blinded wordsmith can still “serve . . . [his] Maker, and present / [His] true account” despite this “calamitousvisitation’I2thus finds its resolution (according to the received approach) in the seeming inertia of the sonnet’s final self-consoling acknowledgmentthat “they also serve who only stand and wait’’-submissive, inactive, obedient, J o b like-for Messianic release from their earthbound afflictions. As a result of this persistent and enduring misperception, Milton scholarship has traditionally considered the poet’s initial meditation on his blindness to be an anthem to passive resignation, an explication 110 z zyxwvutsr zyxwvutsr zyxwvut zyxwvu MILTON QUARTERLY of the poem which has ironically been abetted and promulgated by the oxford English Dictionary itself.’ In point of fact, the first part of the title of this section is but a slightly abridged pastiche of those definitions of the words s m e , stand, and wait in which the OED specificallyinvokes, not only Milton’s Sonnet XIX in genera, but the final line of the poem in particular, to illustrate the historically standard usage of the terms. The full text of “When I Consider. . . ” is reproduced below for ease of reference: When I consider how my light is spent, Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide And that one Talent, which is death to hide, Lodg’d with me useless, though my Soul more bent To serve therewith my Maker, and present My true account, lest he returning chide: “Doth God exact day-labor, light denied,” I fondly ask; But patience to prevent That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best; his State Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest: They also serve who only stand and wait. To stand B.I.5.q 3013 To assume or maintain an erect attitude on one’s feet; With predicative extension: To remain erect on one’s feet in a specified place, occupation, condition, etc. . . . The accompanying action is often expressed by a verb in coordination, to stand and (do something) . . . C. 1655 MILTON, Jonn. XVI [sic], They also serve who only stand and waite. To wait 9, 3669 To be in readiness to receive orders; hence, to be in attendance as a servant; to attend as a servant does to the requirements of a superior. Chiefly const. on: see wait o n . . . c. 1655 MILTON, Sonn. ‘When I Consder’ 14 They also serve who only stand and waite. zyxwvu That the traditional interpretation of this poem relies on the meaning invested in its fourteenth line by long-standing custom and the OED editorial staff becomes self-evident by means of a simple compilation. If one strings together the definitions given by the OED for the versions of the infinitives to serve, to stand, and to wait in which Milton’s Sonnet XIX is directly invoked as an etymological example, the result (emphasized below in bold letters for ease of identification) is as follows: Verb To serve Citation 1.1,2740 According to one of the most authoritative lexicons of the English language, then, the concluding line of “When I Consider How My Light is Spent.. . has, over the course of its more than three and a quarter century history, typically been read “they also perform the duties of a servant who only remain erect on their feet in a specified place in readiness to receive orders”-hence, the encomium to inertia that the poem traditionally represents. Though this is of course both the “received and the “recommended” reading, alternative interpretations are not prohibited by the OED’s normative analysis, and it is from the perspective of the rest of the Miltonic canon that I would like to reconsider “When I Consider,”examining Line 14 in particular, not in the context of reader sympathy for the speaker’s tragic privation, but in terms of the lack of consistency between the standard explication of the words “They ” zyxwvu Definition To be a servant; to perform the duties of a servant.. . C. 1655, MILTON, Sonn., ‘When I Consider’, They also serve who only stand and waite. zy zyxw MILTON QUARTERLY also serve who only stand and wait” and the author’s characteristic responses to frustration, disappointment, bereavement, and failure, both personally and in the vicarious personae of his major literary progeny. Based on such considerations, I contend that it would have been unbearable, if not impossible, for someone of Milton’s talents, ego, and aggressive temperament to subscribe even momentarily to the kind of namby-pamby “pity poor me” resignation implicit in the historical reading of this line, and that traditional rhetorical emphasis on the word “also” has likewise put the pivotal accent squarely on the wrong syllable in terms of the speaker’s meaning. Rather than a sigh (“they also serve, who only stand and wait”), I contend that the final line of the poem is an emphatic declaration (“they also serve, who only stand, and wait”), a subtle modification that makes a monumental difference in the perspective of the speaker, and relies on definitions of the key words serve, stand, and wait quite different from those given in this context by the OED.Tillyard’s discomfort with the historically received image of Milton crouching “in humble expectation, like a beaten dog ready to wag its tail at the smallest token of its master’s attention” at the end of the poem is thus understandable. “Consideredin relation to the rest of Milton’s works,” he writes, Sonnet 19 111 his despair,”but the resolution thus achieved is in no way a “bargain with fate,” and the speaker’s inclination at the end of the poem is toward anything but “repose.”As Stanley Fish has compellingly demonstrated in works like Surprised by Sin and Is There a Text in This Class?, Milton was profoundly fascinated with the elasticity of English grammar and syntax, and was particularly engaged by the proclivity of his native tongue for simultaneouslysaying and unsaying the same thing at a single cognitive moment. By conscious design, such polyvocalities abound in Parrm’ise Lost, Paradise Regained, L y c h , Comus, and Samson Agonistes, and, as Sharon Achinstein has suggested in a different context, are part of the poet’s epistemological strategy, intended to annoy the complacent (those who are smugly self-confident in the accuracy of their own perceptions) with a vague and nagging unease not unlike that experienced by Tillyard in relation to Sonnet XIX-that all that “seems”is “not” what and as it appears to be. Particularly in Milton, zyxwvutsr zyxwvutsrq zyxwvut zyxwvut zyxwvut is an extremely difficult and strange poem. There is in it a tone of self-abasementfound but once again in Milton [presumably, he means in Samson Agonistes] . . . a passive yielding to God’s command. In view of Milton’s normal self-confidence,of his belief in the value of his own undertakings, I cannot but see in the sonnet signs of his having suffered an extraordinary exhaustion of vitality. Yet for all this weakness the sonnet shows the nature of Milton’s greatness. . . [which] lies in [his] having (at least in this sonnet) overcome his despair. He has compounded with his afflictions, and, exacting less from life than at any other time, has made his bargain with fate. In an unusual lowliness, he has found repose. . . . (161-62) Tillyard is of course right (for the wrong reasons) that by the final line of the sonnet, Milton has “overcome our initial speculations[concerning the meaning of the text] generate a frame of reference within which to interpret what comes next, but what comes next may retroactively transform our original understanding. . . . As we read on, we shed assumptions, revise beliefs [and] . . . each sentence opens up a horizon which is confirmed, challenged, or undermined by the next . . . . We read backwards and forwards simultaneously,predicting and recollecting, perhaps aware of other possible realizations of the text which our [chosen] reading has negated Fagleton 77). In Pardise Lost, for example, the reader’s awareness of being deftly and deliberately manipulated by Milton’s protean vocabulary and intense sentence structure grows more and more acute as his or her involvement in the poem proceeds. Participation in this mind-expandingprocess may initially be unnerving to some people, but that is as it is intended to be: before too long, that segment of Milton’s readership that is discerning enough to merit induction into his “fit audience though few” will come to recognize that all of us are destined by the Miltonic method of instruction to be at some moment in narrative time “of the 112 MILTON QUARTERLY Devil’s party without knowing it,” because the wrongheaded acts of embracing that which right reason should compel us to reject, and of accepting what seems at face value to be without trying to see beyond the surface, are prerequisites to this intellectual rite of passage. It is critical to the reader’s accurate comprehension of the work (and indeed, to his or her ability to withstand the sophisticatedbut specious propaganda that much of it contains) that we learn both to recognize the logical fallacies that underlie the persuasive image or idea with which Milton’s program is baiting us, and to rethink, reform, and restructure our perceptual horizons on a continual basis to accommodate each new discovery before the lessons learned are lost: otherwise, we come away from the text intoxicated by “what [the] poem pretends to mean for the purposes of its performance . , . that duplicity beyond all paraphrase that is the mark of all good poetry” (Ciardi and Williams, xxi), remaining smugly confident, for example, that Satan is its hero, that Adam did the right and chivalrous thing by yielding himself to damnation out of loyalty to Eve, and that at the end of Sonnet XIX, Milton “has made his bargain with fate” and “in an unusual lowliness . . . found repose.” Fish describes the mechanics of this phenomenon as follows: 4.’ The find line of Sonnet XIX has been misinterpreted in the same fashion (and for precisely the same reasons) that Milton’s portrayals of the fallen Lucifer and the blind but victorious Nazarite have been misread, because in our pity for the once glorious and classically heroic archangel, the Biblical champion “dark, dark, dark amid the blaze of noon” and “blind among [his] enemies,” and the benighted poet and polemicist abandoned by his Maker l‘in this dark world and wide” (which is the object of “what [each] poem pretends to mean for the purposes of its performance”), we as readers lose sight of the singular devotion to and unflagging faith in God that blazes in the heart of their creator, and we underestimate the obduracy of Milton’s stubborn refusal either to submit or yield his ego or his talent to the vicissitudes of earthly fortune. Throughout his life, the poet believed emphatically that zyxwvutsrq zyxwvu zyx zyxwv Milton consciously wants to worry his reader, to force him to doubt the correctness of his responses, and bring him to the realization that his inability to read the poem with any confidence in his own perception is its focus . . . . The value of the experience depends on the reader’s willingness to participate in it fully while at the same time standing apart from it. He must pass judgment on it, at least on that portion of it which is a reflection of his weakness. So . . . a description of the total response would be, Adam is wrong, no, he’s right, but then of course, he is wrong, and so am I (Fish 43): Such premeditated philological legerdemain on the part of the poet has of c ome resulted in monumental misreading of Milton’s words, his poems, his characters, and the didactic purpose that is at the core of this neo-Socratic “programmeof reader harassment” (Fish the end. . . of learning is to repair the ruins of our first parents by regaining to know God aright, and out of that knowledge to love him, to imitate him, to be like him, as we may the nearest by possessing our souls of true virtue, which being united by the heavenly grace of faith makes up the highest perfection (CPW 2.366-67), and he had at this point devoted an entire lifetime to the study of “true virtue” in an effort to “know God aright”;he was not about to give that up for a reversal of his fortunes now. The “unprofitableservant” who declared that “that one Talent which is death to hide” was now “Lodg’d with [him] useless” and the blind man who some eight years later allegedly justified his resignation to inertia in the line “they also serve, who only stand and wait” was the same person who had as a younger man defended his “tardie moving” and “too much love of Learning” in “the arms of studious retirement” with another direct and telling analogy between his literary talents and the coins distributed by their departing master among his three servants in Matthew 25:13-30, citing “the solid good flowing from due & tymely obedience to that command in the gospel1 set out by the sesing of him that hid the talent,”the “veryconsideration [of which] great comandment, does not presse forward, as soone zyxwvutsr zyxwvu MILTON QUARTERLY as may be, to undergo, but keeps off, w”’ a sacred reverence & religious advisement, how best to undergoe, not taking thought of beeing late, so it give advantage to be more fit; for those that were latest lost nothing, when the maister of the vinyard came to give each one his hire . . . ” (CPW I: 320, emphasis added). In 1642, when it is likely that the sight in his left eye was already waning, Milton would draw on Matthew again, to declare in the second book of The Reason of Church Government that He who hath obtained in more than the scantiest measure to know anything distinctly of God, and of his true worship, and what is infallibly good and happy in the state of mans life, what in it selfe evil and miserable, though vulgarly not so esteem’d; he that hath obtain’d to know this, the only high valuable wisdom indeed, rememhng also that God, even to a strictnesse, requires the improvement of these his trusted g$s, cannot but sustain a sorer burden of mind, and more pressing than any supportable toil, or waight, which the body can labour under, how and in what manner he shall dispose and employ those summes of knowledge and illumination, which God hath sent him into this world to trade with (CPW1: 801, emphasis added). 113 made thee (CPW 1: 801). It is here too that the poet exhorts his readers to respond stoically to adversity-though it is to ecclesiastical rather than ocular affairs that he refersdeclaring “if God come to trie our constancy, we ought not to shrink or stand the lesse firmly for that, but passe on with more stedfast resolution to establish the truth, though it were through a lane of sects and heresies on each side” (CPW 1: 794-95). “It is not so wretched to be blind as it is not to be capable of enduring blindness” (CPW 4: 584)6 he says in the Second Defense; averring that his “resolutions are too firm to be shaken . . . that I have been enabled to do the will of God; that I may oftener think on what he has bestowed rather than what he has beheld; that, in short, I am, unwilling to exchange my consciousness of rectitude with that of any other person,”preferring physical blindness to the intellectual benightedness of the hapless “Morus,” zyxwv Later in the same work, a still-sighted Milton predicts the self-castigationhe would endure were he to refuse to descend into the “cool element of prose” in defense of church and nation, a full ten years before the complete loss of his vision: as long as in that obscurity, in which I am enveloped, the light of the divine presence more clearly shines; then, in proportion as I am weak, I shall be invincibly strong, and in proportion as I am blind, I shall more clearly see. O! that I may be thus perfected by feebleness, and irradiated by obscurity! (CPW4: 584). zyxwvu zyx zyxwv zyxwvu What matters it for thee, or thy bewailing?When time was thou couldst not find a syllable of all thou hadst read or studied, to utter in her behalfe. Yet ease and leasure was given thee for thy retired thoughts, out of the sweat of other men. Thou hadst the diligence, the parts, the language of a man, if a vain subject were to be adorn’d or beaudi’d, but when the cause of God and his Church was to be pleaded, for which purpose that tongue was given thee which thou hast, God listen’d if he could hear thy voice among his zealous servants, but thou wert domb as a beast; from hence forward be that which thine own brutish silence hath These do not strike me as the declarations of someone who could wallow in the kind of indolent self-pity that the last line of Sonnet XIX is historically assumed to portray. In the decade following the publication of Sonnet XIX, the same emotionally and artistically bankrupt individual who in that short poem showed “signs of his having suffered an extraordinary exhaustion of vitality” composed and published in rapid succession his translations of Psalms 1 through 8(1653), The Second Defme of the English People (1654), Defmio pro se and Sonnets 18 and 20 through 22 (1655), Sonnet 23 (1658), A Treatise of Civil Power and Considerations Touching the Likeliest Means to Remove Hirelings Out of the Church (1659), and The Ready and Easie Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth (1660); began his work zyxwvutsr zyxwvutsrq zyxwvuts zyxwvu 114 zyx zyxwvu MILTON QUARTERLY on De Doctrina Christians and The History of Britain; and, according to his nephew, Edward Phillips, drafted much of the ten-book version of Paradise Lost (c.1663), all of this in total blindness, in the midst of political upheaval (the abortive reign of the Cromwell Protectorate and the restoration of Stuart monarchy); personal troubles (the deaths both of his first wife, Mary Powell Milton, in 1652, and of his second wife, Katherine Woodcock Milton, in 1658; of his only son, John, at fifteen months of age, in 1652; and of his youngest daughter, Katherine, in infancy, in 1658); and his personal experience of the paranoia that gripped all unexcluded Commonwealth men in response to the restored king’s gruesome reprisals against his and his father’s enemies, living and dead, exacerbated by the public burning of Eikonoklastes and Dt$msio prima by order of the House of Commons in June of 1660. He had also more than likely by this time written the famous invocation to Light that, like Sonnet 19, begins in the style and manner of a jeremiad, with the same sad tones of bereavement as those heavy notes that weight the poet’s words at the beginning of the shorter poem: Hail, holy Light, offspring of Heav’n first born . . . Thee I revisit safe, And feel thy sovran vital Lamp; but thou Revisit’st not these eyes, that roll in vain To find thy piercing ray, and find no dawn; So thick a drop serene hath quenched thir Orbs, Or dim suffusion veil’d. Then feed on thoughts that voluntary move Harmonious numbers, as the wakeful bird Sings darkling, and in shadiest covert hid Tunes her nocturnal note. (3.27-37) Again the tone changes, as it does in the sonnet (“‘Doth God exact day-labor,light deni’d?’/ I fondly ask); resolve reverts to misery as the poet realizes that no matter how much he wills it otherwise, no amount of resolution on his part can change his situation: Thus with the year Seasons return; but not to me returns Day, or the sweet approach of ev’n or morn, O r sight of vernal bloom, or summer’s rose, Or flocks, or herds, or human face divine; But cloud instead, and ever-during dark Surrounds me, from the cheerful ways of men Cut off, and for the book of knowledge fair Presented with a universal blank Of Nature’s words to me expung’d and razed, And wisdom at one entrance quite shut out. (3.40-50) The fallacy of this wrenchingly poignant but nonetheless self-pitying argument-that true wisdom, which is the product of the internal promptings of the Paraclete, needs no “entrance”but an open mind, and has therefore never been “quite” (or even partially) “shut out” of Milton’s existence-is exposed as swiftly by the poet’s own patience in the invocation as the fallacy of his complaint in “When I Consider” is exposed by its personification. Like “blind Thamyris and blind Maeonides, / And Tiresias and Phineas prophets old,”Milton has lost “out-sight”only to gain insight, a greater boon than his blindness is a bane: zyxwvut Yet that way, the speaker knows, lies madness. Poised on the brink of despair, the monody here retracts itself (as it does in Sonnet 19) in the face of the poet’s determination to press onward undaunted, and to make his way as best he can toward the fulfillment of his duty and his destiny despite the vicissitudes of fortune: Yet not the more Cease I to wander where the Muses haunt. . . Nightly I visit; nor sometimes forget Those other two equaled with me in fate, So were I equaled with them in renown, Blind Thamyris and blind Maeonides, And Tiresk and Phineas prophets old: So much the rather thou, celestial Light, Shine inward, and the mind through all her powers Irradiate, there plant eyes, all mist from thence Purge and disperse, that I may see and tell Of things invisible to mortal sight. (3.51-55) Clearly, as the preceding selection demonstrates, the epic poet had by this point learned what the zy zyxw zyxwvu zyxwv MILTON QUARTERLY 115 zyxwvutsr young sonneteer had yet to discover, that is, to embrace that “patience” that is the corollary-not the antithesis-of the “invincible might” of the heroic Deliverers who “with winged expedition / Swift as the lightning glance” (SA 1283-84) execute God’s errands, the patience that is “more oft the exercise / Of saints” than of warriors, “the trial of thir fortitude, / Making them each his own Deliverer / And victor over all / That tyrannie or fortune can inflict” (SA 1287-91); though indeed, “thousands at his bidding speed / And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest: / They also serve who only stand and wait.” This insight was for Milton the critical lookedfor “source of consolation from above,” the “secret refreshings, that repair his strength, / And fainting spirits uphold (SA 663-66) that have not yet come to his Samson at the conclusion of Manoa’s visit-without the assurance of such inner prompting of the spirit, the poet, too, would doubtless pray the “one prayer” that yet remains to the Nazarite at the nadir of his despair-“speedy death / The close of all my miseries, and the balm” (SA 649-51). Rather than the whimpering lament of a defeated has-been, then, I envision Sonnet 19 as the first major milestone in the poet’s progress toward reformation of the heroic ethos of classical antiquity, that is, as the first in a series of penetrating inquiries that lead from the personal (“What can I do now?”) to the universal (“What can any Christian man do now?”)in the face of the shifting horizons of epistemological expectation confronted by the poet in little in his personal affairs, by the English nation in its political affairs, and by western civilization at large in the kaleidoscopic reality of the seventeenth century. Even as a young man, Milton was possessed of a clear sense of mission (“to defend the dearest interests, not merely of one people, but of the whole human race, against the enemies of liberty” (CPW4: 557-58) and to “leave something so written to aftertimes, as they should not willingly let it die“ (CPW 4: SIO), and his successes only reinforced what he later characterized as his “full experience of the divine favor and protection,” a “consciousness of rectitude” (CPW 4: 557-58), and “singular marks of the divine regard” (CPW 4: 558)-outrageous boasts for a hellfire-fearing Independent to make unless he indeed felt the rousing motions of the Holy Spirit stirring within him. He was aware, even while composing The Reason of Church Government,that his greatest work was yet to come (one “not to be raised from the heat of youth, or the vapors of wine, . . . but by devout prayer to that eternal Spirit who can enrich with all utterance and knowledge, and . . . touch and purify the lips of whom he pleases,” CPW4: 821), and that his prose diatribes on politics and popery were digressions merely, an “interruption”of his true calling permitted with “smallwillingness”on his part, which had forced him to leave “a calm and pleasing solitariness,fed with cheerful and confident thoughts, to embark in a troubled sea of noises and disputes,” and, distracted “from beholding the bright countenance of truth in the quiet and still air of delightful studies,” induced him to “meddlein these matters” (CPW4: 821) of civil and ecclesiastical controversy, having the “use . . . but of [his] left hand (CPW 4: 808). Clearly, Milton’s agenda at the prime of his life did not anticipate the advent of an affliction so inimical to his objectives as the loss of his eyesight, nor did it accommodate such a calamity even when he was forewarned of its imminent approach by his physicians. Literally given a choice between “the loss of [his remaining] sight or the desertion of [his] duty” late in the autumn of 1649 (when, already blind in one eye, he was asked to write a response to Salmasius’ Defensio Regla pro Carolo Primo),Milton declared that he “would not have listened to the voice of [Alesculapius himself‘ delivering the same prognosis at that time, but preferred instead to heed “the suggestions of the heavenly monitor within [his] breast” that prompted him to “makethe short interval of sight which was left [him] to enjoy as beneficial as possible to the public interest” (CPW4 588). He composed his Defario Pro Populo Angficuno (published in March, 1651) in fulfillment of that commitment, thereby “procu~fing] great good by little suffering” (CPW4:588), but also consciously sacrificing what was left of his precious vision in the bargain. The descent of total darkness on eyes that were even in blindness “as unclouded and bright as the eyes of those who most distinctly see” (CPW 4: 583) meant, in a world of quill pens and parchment paper, the end of the poet’s literary career (that “one talent . . . now lodg’d with [him] useless” because, by 1652, he could neither see to write, nor read what he zyxwvuts 116 zyxwvuts zyxwvut zyxwv zyxwvu zyxwvutsr MILTON QUARTERLY had written). Blindness bereaved him not only of the chief of hs five senses, but also of the primary means whereby he was destined from birth to fulfill his covenant with God: so that what some unsympathetic souls took to be the Almighty’s public humiliation of a once-favored son (in retribution, his enemies said, “for the transgressions of [his] pen,” (CPW 4: 587) actually served as a catalyst to force Milton Samson-like to re-evaluate his youthful convictions, not only of the “inward prompting” (CPW 4: 810) both of sacred mission and manifest destiny, but also of the “divinefavor and protection” that seemed somehow to have deserted him in his hour of greatest need. Shaken out of his complacent and almost smug self-assurance by the harsh realization that heavenly approbation could (seemingly) be withdrawn as mysteriously as it had been bestowed (the noble experiment of the Good Old Cause inexplicably having failed), the poet must have wondered as his Samson does what was to become of one who “blind among his enemies” could no longer draw upon the only strength on which he had ever relied: for perhaps the first time in his life, Milton’s ability to perform those tasks necessary to fulfill the heroic destiny he had always believed he was born to consummate was cast seriously into doubt, and since it did not now seem that he could make a fair return on his Master’s investment in him by means of his pen (in keeping with the “profitable servant” analogy of Matthew 25.13-30 and Luke 19.12-26), his soul was likewise in jeopardy. Cut off from all access to that “onetalent” which was his only opportunity for to balance the ledger sheet and present thereby his “true account,” Milton remained nonetheless “more bent / To serve therewith [his] Maker” in much the same way as he had always done, and (perhaps more significantly) had always been confident he would be able to do. The question now was how such service was supposed to be accomplished (“Doth God exact day labor, light deni’d?”),and for the trustee of an extraordinary “all-of-God’s-eggs-in-one-basket”capability thus totally, inexplicably-and, one would almost say, cruelly-incapacitated, the challenge could not have been an easy one to answer. Milton’s carefully considered and deeply personal response to this paradox was, it seems to me, the catalyst that initiated the poet’s quest for a definition of Christian heroism answerable to his own predicament and objectives, a realignment and redirection of his energies that would permit him even despite the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of his blindness to “get even” with Heaven (in the sense that George Herbert expresses a determination to settle the score with his Savior and “revenge [himself] on [God’s] love”8 in poems like “The Thanksgiving”). Like Herbert, Milton was doomed to failure even before he began, since, as both poets came to recognize, there is nothing mortal beings can do to requite the Redeemer quid pro quo for His sacrifice, no matter how earnestly they might attempt to replicate the “labors huge and hard, too hard for human wight” accomplished once and forever by the “most perfect Hero” of past, present, and future history (“The Passion” 2.13-14); or how zealously they might strive to make their individual offerings count: the balance sheet simply will not balance, because the weight of the world is too great a burden for earthbound shoulders to bear. Paradise Regained is, I think, Milton’s variation on this theme, an exploration not of the impossible-toemulate archetype of Christian heroism reified in the self-immolation of Messiah-in-man at Golgotha (“Thenfor thy passion-I will do for that- / Alas, my God, I know not what,” says Herbert), but of the less numinously charged but more identifiably human aspects of the man (Christ) Jesus’ victory over the temptations of the world, the flesh, and the Devil in the wilderness, no doubt in conscious recognition of the fact that the latter, at least, supplies a paradigm of “standing and waiting“ more susceptible of accommodation to the limitations of purely mortal capability. From the Lady of Comtrs and the narrators of Lycidas and “When I Consider,” to Samson, Adam, Eve and even Jesus himself, Milton has been exploring the potential for human heroism in New Testament terms, and each of his human protagonists thus represents a discernibly more mature approximation of the imitatio Christi against a backdrop of increasing challenge in adversity. Their trials begin with the atypically Christian responses of the Lady and the speaker of the elegy to classical literary situations (i.e., the attempted rape of a human female by a god or demigod, and the premature death of a hero), and culminate on one hand in the willing sacrifice of egocen- zyxwvutsrq MILTON QUARTERLY zy 117 zyxwvu tricity to the greater glory of God that enables Samson actively and heroically to finish a life heroic (1710-11), and on the other in the more subdued, serene, and seemingly passive form of valor that the man(God) Jesus himself exhibits at the climax of Parudise Regained (a resignation of the self which is for him but a foreshadowing of the supreme act of heroism in which he alone will and can ultimately engage). Inherent in each confrontation with sin is the opportunity to fall, to give in to the weakness of the body or the soul (self-temptedor beguiled), to despair rather than to hold fast to one’s convictions and stand firm against a compelling seduction. The point is that, as the Adversary tells his adversary on the temple spire, “to stand upright will ask thee skill” (4.551-52): in any struggle, it takes the steady exertion of a force equal and opposite to that of one’s assailant simply to maintain apparent stasis, but the seeming motionlessness of such sustained resistance is-as the Lady in Comus and Christ on the pinnacle aptly demonstrate-by no means the same as actual inertia (“that property of matter by which it retains its state of rest or of uniform rectilinear motion so long as it is not acted upon by an external force”).” As Samson, Adam, and Eve must learn in the process of atoning for their respective sins, to withstand the temptation to act wrongly and thereby stand one’s ground requires an expenditure of energy equal to or greater than the force of the impulse to transgress: if an individual standing still is pushed backward by an opposing force with fifty pounds of pressure, he or she must push back with at least the same power and intensity in the opposite direction simply to remain erect, even though to the casual observer neither the push-er nor push-ee will appear to be in motion: like the phoenix in Samson Agonistes, the Christian hero is “then vigorous most / When most inactive deem’d (1704-05). This is the import of Raphael’s warnings to Adam and Eve at 6.520 and again at 8.633 that the bliss they enjoy is contingent: Him whom to love is to obey, and keep His great command; take heed lest Passion sway Thy Judgment to do aught, which else free Will Would not admit; thine and of all thy Sons The weal or woe in thee is plac’t; beware. I in thy persevering shall rejoice, And all the Blest: stand fast; to stand or fall Free in thine own Arbitrement it lies. Perfet within, no outward aid require; And all temptation to transgress repel. (8.633-43) Notice that all of the verbs of Raphael’s injunction require Adam either to continue doing that which he is already engaged in doing (“be strong, live happy, and love, but first of all / Him whom to love is to obey, and keep / His great command; [persevere]; “stand”;“stand fast”),to be watchful (“beware”;“take heed), or not to do that from which he has heretofore refrained (“[do not let] Passion sway / Thy Judgment to do aught, which else free Will / Would not admit”; “all temptation to transgress repel”): Adam does not have to do anything new to preserve his sinless state (that is, it will be enough for him to “continue steadfastly,” or persevere” in his thus far intact obedience), but he must actively resist the impulse to take new (wrong) action in the form of succumbing to temptation-that is to say, of engaging in disobedience, which is the negation of the positive action of obeying God, and not doing what the Creator has prohibited.12 Theologically, the word “persevere”takes on an even keener significance in this context: Raphael is not only reminding Adam to refrain from doing what God has commanded him not to do, he is also exhorting him “to continue in a state of grace to the end, leading to eternal salvation,”” to stand in his righteousness rather than fall into sin. The real transgression committed by our First Parents is not the literal act of tasting of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, but a failure in both cases to rely on God’s loving grace (ugupe) already granted to satisfy all of their needs: Eve’s attempt to accelerate the workings of b i r o s by trying to ascend the next rung of the Great Chain of Being before God has decreed that she should do so fails dismally, as does Adam’s preemptive and impulsive decision to seek damnation with Eve rather than attempt to intercede zyxwvu z zyxwvu That thou art happy, owe to God; That thou continu’st such, owe to thyself, That is, to thy obedience; therein stand. (6.520-23) Be strong, live happy, and love, but first of all 118 MILTON QUARTERLY on her behalf (trustingin the benevolence of whatever alternatives the Creator may ~ffer).‘~ Salvation is granted them because, having considered other courses of action (counter-incrimination, literal annihilation, suicide, abstinence, etc.), they decide to stand and wait patiently for God‘s judgment, acknowledging the willfulness of their transgressions with no attempt at self-exculpation, and trusting guilelessly and completely in God’s mercy and love, as they should have done from the start.15 Like Adam and Eve and Samson, too, the narrator of Lycidas who demands to know “What boots it with incessant care / To tend the homely slighted shepherd’s trade?” at the beginning of the poem must learn that it is God’s will and God’s timetable that will determine his “fair Guerdon,” and not his own impatient desires: those who remain steadfast in their faith in God’s beneficence and do God’s service in whatever manner and in accordance with whatever schedule the Lord directs them to follow (and not when and as they please) will find the “fresh woods and pastures new” that in this case equate to earthly salvation, when the providential time is right. Like Samson and the speaker of Sonnet 7 (“How Soon Hath Time”),the narrator of Lyctdar must learn to stand fast in virtue and wait in circumspection when everything in him wants impulsively to run, “to burst out into sudden blaze”: it is the “perfect witness of all-judgingJove / As he pronounces lastly on each deed that will bring him the everlasting laurel he craves, rather than the approbation of men. Samson’s appetite for the worldly glory that is the “fairGuerdon” of classical epic heroism must likewise be curbed and redirected before he can merit redemption and the restoration of grace: it is his resistance against the tandem impulses to yield to his overwhelming despair and his classical berserker’s egocentricity at the end of his days (along with his rejection of the invitations he receives from his wellmeaning father and his treacherous wife to escape God’s punishment and live a life of ease) that allow him ultimately to rise above his own misery and indignation and say, Christ-like, “thy will [rather than my will] be done,” convinced by “some rousing motions within [himy that God intends to let Samson quit himself like Samson: (“This day will be remarkable in my life / By some great act, or of my days the last” 1387-88). Though he bears the affronts he suffers at the hands of the Philistines in general and Dalila and Harapha in particular without complaint (“All these indignities . . . these evils I deserve and more, / Acknowledge them from God inflicted on me /Justly. . . . ” 1168-71), and can say with “confidence”that he ”yet despai~fs]not of his final pardon / Whose ear is ever open; and his eye/ Gracious to readmit the suppliant” (1171-73), it is only when he is able to put aside the warrior’s pride and yearning for recovery of his lost glory that is inherent in his initial refusal to attend the Dagonalia (“Can [the Philistines] think me so broken, so debas’d / With corporal servitude, that my mind ever / Will condescend to such commands? . . . I will not come” 1335-42), that he is truly able to take right action and willingly go where he is bidden, to the greater glory both of his God and of himself. But if Samson reflects the via activa of Christian heroism, then it is Satan (and not the speaker of Sonnet 19) who is his antithesis, that is, the distinction is between wrong action for personal glory, and right action for the glory of God, not motion versus stasis per se. zyxwvut zyxwvutsrq zyx zy zyxwvut The God of Paradise Lost offers the therapeutic gift of prophecy to Adam and Eve only if they accept His judgment ‘patiently.’ . . . ‘They also serve who only stand and wait’-so Milton stood ready for his future. Seen with the eye of God or the eye of a prophet, waiting was indivisibly part of acting. His restraint was a deed of faith: he must wait with the belief that his future, complete in the mind of God, would come round before he died. Impatient restlessness, the most dangerous kind of inaction, was the abiding temptation to violate the divine schedule. Forcing time, relinquishing himself to the motions of a guilty disease, would have constituted a faithless indictment of God-and therefore an indictment of the life God held in trust.-Waiting for God was waiting for himself. (Kerrigan 264) zy Because we, too, are fallen, and too frequently guilty of a dangerous impatience, we are supposed to read the final line of Sonnet 19 as a sigh of resignation, just as we are supposed to see the Lady of Comus as frigid and puritanical in contrast to her pleasure-obsessed antagonist, as indeed we are supposed to see Aeneas zyxw zyxwvu zyxwv z zyxwvuts MILTON QUARTERLY (and even Milton himself) in the fallen archangel and the derelict Old Testament warrior. We are meant to applaud the unfallen Adam, too, in the uxoriously “heroic” gesture of courtly love implicit in his declaration to the fallen Eve that “with thee,” Certain my resolution is to Die; How can I live without thee, how forego Thy sweet Converse and Love so dearly join’d, To live again in these wild woods forlorn? (9.906-09) because in our similarly fallen state, we fail to comprehend the spiritually damnable nature of such a seemingly chivalrous and praiseworthy action, and are touched by its selflessness rather than appalled (as we ought to be) by its atheism. But we are also in the contexts of Lyculus, Sonnet 19, Paradise Lost, and Samson Agonistes supposed to become sensitized to this kind of psychological entrapment, and to learn to see the initially seductive images of carpe diem hedonism, irredeemable despair, cockalorum vainglory, wounded pride, self-exalting egocentricity, and devoted uxoriousness for the sins they really are. We are supposed to reject them, just as the Lady, Adam, Eve, and Samson ultimately do, in imitation of Christ’s matter-of-fact rejections of the temptations of the flesh, the world, and the devil in Paradise Regained, but-let them who have ears to hear it hear-the fact that we are supposed to do something doesn’t always mean that we accomplish it. Perhaps ironically in terms of what we have been considering here, it is the man (God) Jesus himself who in the brief epic demonstrates most aptly the point of the final line of Sonnet 19, which is, that by not falling when they might, and not acting when they shouldn’t act, they also serve (“render habitual obedience to, do the will of”) his Father16who only stand (“remain steadfast, firm, secure, and the like”) l7 and wait (“in Bible phrase, to place one’s hope in God).18 Averett College 119 opposition in Pro Se Defensio makes it very clear that he regarded Salmasius, Du Modin, and More as such. In a letter to Henry Oldenburg written the same year, and cited in John S . Diekhoff‘s Milton on Himself(136), Milton calls the loss of sight “a sorer affliction than old age,” but nowhere except in the traditional explication of Sonnet XM is there any suggestion that he let it overwhelm him. All citations from the Oxford English Dictionary refer to the Compact Edition (New York: Oxford UP, 1985). As evidenced by the excerpts contained in Edward Jones’s excellent compilation, although a handful of scholars (Mitsuo Miyanishi, Edward Tayler, James Jackson, Paul Baumgartner, and Akira Arai, among them) have interpreted the terminal line of the sonnet much as I do here, the overwhelming majority have concurred with Tillyard that, as Joseph Pequigney writes, “the speaker must not only be able to attend God’s will, but he must also be willing to accept an inactive life as legitimate service to God. . . Oones 100). “ ‘See the discussion on 38-43. Put another way, this ‘konvenient modern theory suggests that we are meant to admire Satan’s dynamism and then, thanks to the author’s many promptings, realize we have pledged allegiance to an unworthy hero” (Danielson 60), a “convenient modern theory” with which I wholeheartedly concur, and like Fish, would extend (mutatis mutandis) to all of the characters of Paradise Lost. zyx zyxwvut NOTES Though Milton had no political enemies capable of doing him more than verbal damage until the restoration of Charles 11, his perception of the Even today, there are critics of Paradise Lost who insist with Blake (Songs of Innocence, 1789) that “Miltonwas of the Devil’s party without knowing it,” and astute readers of Samson Agonistes who continue Johnson’s search for the “missingmiddle” of Milton’s “dramatic poem,” entrapped by Milton’s epistemological strategy into seeing only half-truths and shadows. All Miltonic quotations and translations are from Hughes, Complete Poems, unless otherwise specified. ’In Ad Putrem (Hughes 84) Milton declared him- zyxwvutsr zyxwvut zyxwvutsrqp MILTON QUARTERLY 120 self to have been “born a poet,” and repeated his statements of mission again and again in such works as The Reason of Church Government and the Second Defense; there is no evidence that he ever dcviated from his youthful intuition that fame would come to him through a certain poetic “style [that] by certain vital signs it had,” was “by sundry masters and teachers both at home and at the schools”found to be “likely to live” (Reason of Church Government, in CPW 1: 809). the loss or lack of the power to act . . . . What happens when Adam eats the forbidden fruit then is not an act, but the surrendering of the power to act. Man is free to lose his freedom, and there, obviously, his freedom stops. His position is like that of a man on the edge of a precipice: if he jumps, it appears to be an act, but it is really the giving up of the possibility for action, the surrendering of himself to the law of gravitation which will take charge of him for the brief remainder of his life. In this surrendering of the power to act lies the key to Milton’s conception of the behaviour of Adam. A typically fallen human act is something where the word “act”has to be in quotation marks. It is a pseudo-act, the pseudo-act of disobedience, and it is really a refusal to act at all (416). zyxwv zyxwvu zyxwvu George Herbert, “The Thanksgiving.” Unless otherwise identified, all Herbert citations will reference the C.A. Patrides edition of The English Poems OfGeorgeHerbert pondon: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1988). “The Passion,’’Easter 1630,11.13-14 (Hughes 62). It is interesting, in view of the fact that this is the only direct attempt Milton ever made to deal with the Passion, that the poem bears the postscript “This Subject the Authorfinding to be above the years he had, when he wrote it, and nothing satisfied with what was begun, left it unfinisht.” lo Like Samson, Adam is thus given an opportunity to engage in a true imitatio Christi, but his “chivalrous” love for Eve (amor)supersedes his spiritual love for God (caritar),and overwhelms the right reason that should lift his eyes toward heaven. Adam’s heroism, as well as Eve’s, lies in rectifying this disobedience of the “first and great commandment, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, with all thy soul, and with all thy mind (Matthew 22:37) implicit in the injunction against the “apple”; John Steadman’s argument in Milton and the Paradoxes of Renaissance Heroism that, unlike Achilles, Odysseus, Aeneas, Orlando, Ruggiero, and Redcrosse, “Adam and Eve are corrupted, not purified, by trial,” so that “in their case the test of virtue results in the contamination of original purity rather than in purification of a native impurity” (183) therefore misses the point. Like the Chosen People of the Old Testament, Adam and Eve (with a purity unique in human history to themselves and Christ) find their initial covenant with the Lord too hard to perform; but unlike Satan, once fallen, they merit and rely in full faith upon an Intercessor, and are re-purifiedby his mercy. zyxwvutsrq z The American College Dictionary (New York: Random House, 1968): 621. The American College Dictionary, “persevere” (903). l 3 American College Dictionary, “perseverance,” Definition 2 (903). The OED (1.e) simply says “to continue in a state of grace” (2140). l2 In The Christian Doctrine I, xi, Milton explains that “actual sin” is so called not that sin is properly an action, on the contrary it is a deficiency, but because it usually exists in some action. For every action is intrinsically good; it is only its misdirection or deviation from the set course of law which can properly be called evil (CPW6: 391). The quotation is glossed by Northrop Frye in “The Story of All Things” (FiveEssays 20-21) as follows: An act is the expression of the energy of a free and conscious being. Consequently, all acts are good. There is no such thing, strictly speaking, as an evil act; evil or sin implies deficiency, and implies also l5 Georgia Christopher points out in her discussion MILTON QUARTERLY 121 on the “conspicuousvirtue” of Milton’s devils (199) that the “elision of degree in Hell” so that there are only two hierarchical categories, “Satan” and “lesser devils,”despite the honorifics suggesting otherwise, Though some thus fell away, others stood fast, Remaining glorious martyrs to the last. 1667 MILTON P.L. 111, 99, I made him just and right Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall (3013). reflects the Protestant abolition of [Roman The Oxford English Dictionary, (v.) “wait,” definition II.14.h: Catholic private] confession and of precisely calibrated penances [corresponding to ‘a precisely calibrated hierarchy of venial and mortal sins’]. To be sure, Protestants developed their casuists, but their piety purported to erase gradations of sin and concentrate upon the heart’s primary orientation. Moral calculus began with faith. The biblical underpinning for this point, cited by Milton as by Luther before him, was Romans 13:23: ‘Whatsoever is not of faith is sin’ (YP 6:639, Luther’s Works, 26250). This view no longer Localized sin in carejiul categories, but spread it into all areas of existence, including those normaLLy reserved for virtue. The most irirtuous’ action without faith was sinful; conversely, ?loth’ (or mereLy standing and waiting) might be a most heroic act offaith. [Italics added.] z ‘’ In Bible phrase, to place one’s hope in (God). Very common in the Bible of 1611; rendering several Hebrew verbs of identical meaning. zyxwvutsr zyxwvutsrq Obviously, I do not concur with her implication that either the “standing”or the “waiting”in Milton’s poem equates to “sloth,” though I would agree (as argued earlier in this paper) that it equates to apparent inaction (deliberate failure to act impulsively, based on faith), which is not the same thing. 1535, Coverdale, Ps.LXI.1 My soule wayteth only vpon God, for from him commeth my helpe . . . (3669). WORKS CITED The American College Dictionary. New York: Random House, 1968. Christopher, Georgia. ”Milton and the reforming spirit.” Danielson 197-205. zyxwvut zyxwvuts l6 The Oxford English Dictionary, (v.) “serve,” definition I.7.b, which (ironically) refers to Line 11 but not Line 14 of “when I Consider,” though the distinction is virtually indiscernible: To render habitual obedience to, to do the will of (God, a heathen deity, Satan) . . . c. 1655, MILTON, Sonnet, ‘When I Consider’, 11 Who best Bear his milde yoak, they serve him best (2740). ?%e oxford English Dictionary, (v.) “stand,” definition B.I.9.b: ” Ciardi, John, and Miller Williams. How Does a Poem MeanZ2nd ed. Boston: Houghton, 1975. CPW. See Milton. Danielson, Dennis, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Milton. New York: Cambridge UP, 1994. Diekhoff, John S. Milton’s Paradise Lost: A Commentary on the Argument. New York: Humanities P, 1958. Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory: An Introduction. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1983. Fish, Stanley Eugene. Surprised By Sin: ?%eReader in Paradise Lost. New York: Macmillan, 1967. Freeman, James A. Danielson 51-64. fig. To remain stedfast, firm, secure, or the like . . . 1657 BILLINGSLY Bruchy-Martyrot. xi.35 Frye, Northrop. “The Story of All Things.” The 122 zyxwvutsr zyxwv zyxwvuts MILTON QUARTERLY Return of Eden: Five Essays on Milton’s Epics. London: Routledge, 1966.3-31. Hughes, Merritt Y. John Milton: Complete Poems and Major Prose. New York: Odyssey, 1957. Bees in My Bonnet: Milton’s Epic Simile and Intertextuality Jones, Edward. Milton’s Sonnets: An Annotuted Bibliography, 1980-1992. Binghamton: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1994. William Moeck Kerrigan, William. The Prophetic Milton. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1974. zyxwvutsr zyxwvuts Miller, David. john Milton: Poetry. Boston: Twayne, 1978. Milton, John. Complete Prose Works ofjohn Milton. 8 vols. in 10. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1953-82. The o x f r d English Dictionary, Compact Edition. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Patrides, C. A. The English Poems of George Herbert. London: Dent, 1988. Steadman, John. Milton and the Paradoxes of Renaissance Heroism.Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1987. Tillyard, E.M.W. Milton. New York: Collier, 1966. The obvious debts to Homer and Virgil in Milton’s Bee Simile were initially recorded in Patrick Hume’s “Notes on Paradise Lost” (1695), though the extended comparison was argued nearly a generation ago as referring us obliquely to Shakespeare and Spenser. In the following essay, I shall briefly review arguments made by Harold Bloom and taken up most conspicuously by John Hollander and John Guillory, for two reasons. First I would like first to demonstrate that, as the Bee simile metamorphoses over nearly thirty lines, it also alludes to Renaissance and classical precedents hitherto unsounded. Secondly, I would like to breathe new life into the question: what is the difference between a source and an intertext? I have reservations about the validity of the latter as a concept supplanting the former term for literary critics, though my qualms are voiced from the inside, for in my analysis of Milton’s passage I, too, hear echoes, but of Tasso. In conclusion, I argue that the strategies of the source-huntersand intertextualists on Milton are worth revisiting, not in order to reiterate that the difference hangs on a changed understanding of how language functions, but to suggest that our ability to recognize an intertext, as an extension of our ability to recognize a source, is a working out of an aesthetic response to literature. Bloom dubbed the bravura gesture of Paradise Lost towards its literary past as transumptive, and, followed by Hollander and Guillory, he uses the rhetorical trope of transumption or metalepsis to discuss a Miltonic style. Although a study of trope as defined by the rhetorical treatises would not lead the aspiring orator to suspect it was more than a curiosity, the trope is far more important for literary critics.’ Because it involves a doubling of figures, or denotes a way of referring to something by the omission of an z