J. Comp. Path. 2008, Vol. 138, S1eS43

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa

Histopathological Standards for the Diagnosis of

Gastrointestinal Inflammation in Endoscopic

Biopsy Samples from the Dog and Cat: A Report

from the World Small Animal Veterinary

Association Gastrointestinal

Standardization Group

M. J. Day*, T. Bilzer†, J. Mansell‡, B. Wilcockx, E. J. Hall*, A. Jergensk,

T. Minami{, M. Willard‡ and R. Washabau#

*

University of Bristol, Bristol, UK, † University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany, ‡ Texas A&M University,

College Station, TX, USA, x Histovet, Guelph, Canada, k Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, { Pet-Vet, Yokohama,

Japan and # University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN, USA

Summary

The characterization of inflammatory change in endoscopic biopsy samples of the gastrointestinal mucosa is

an increasingly important component in the diagnosis and management of canine and feline gastrointestinal

disease. Interpretation has hitherto been limited by the lack of standard criteria that define morphological

and inflammatory features, and the absence of such standardization has made it difficult, if not impossible,

to compare results of retrospective or prospective studies. The World Small Animal Veterinary Association

(WSAVA) Gastrointestinal Standardization Group was established, in part, to develop endoscopic and

microscopical standards in small animal gastroenterology. This monograph presents a standardized pictorial

and textual template of the major histopathological changes that occur in inflammatory disease of the canine

and feline gastric body, gastric antrum, duodenum and colon. Additionally, a series of standard histopathological reporting forms is proposed, to encourage evaluation of biopsy samples in a systematic fashion. The

Standardization Group believes that the international acceptance of these standard templates will advance

the study of gastrointestinal disease in individual small companion animals as well as investigations that compare populations of animals.

! 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: cat; diagnostic standards; dog; gastrointestinal biopsy; gastrointestinal inflammation

Introduction

The diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disease

in the dog and cat are increasingly based on the

collection and interpretation of mucosal biopsy samples

obtained endoscopically from one or more gastrointestinal sites. There are many stages in this process in

which error may be introduced, thereby influencing

the clinical outcome. These stages include the endoscopic biopsy procedure, the processing and embedCorrespondence to: M.J. Day (e-mail: m.j.day@bristol.ac.uk).

0021-9975/$ - see front matter

doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2008.01.001

ding of the small and fragile tissue samples, and the

microscopical interpretation of the tissue changes by

the diagnostic pathologist (Willard et al., 2001, 2002).

For many clinicians and pathologists, the histopathological interpretation has proved to be the most

contentious and frustrating step in the diagnostic

sequence. This interpretation may be complicated by

inadequacies in the number and quality of the tissue

samples, by fragmentation and unfavourable orientation of these samples during processing, and by the

lack of an internationally accepted set of standards for

evaluating microscopical changes present in the tissues.

! 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

S2

M.J. Day et al.

The aims of the pathologist are to distinguish normal

from diseased tissue, to characterize the nature and

severity of tissue changes, and to provide an accurate

morphological or aetiological diagnosis, thus facilitating formation of a prognosis and appropriate therapy.

Some histopathological diagnoses, for example, the

identification of adenocarcinoma or overt alimentary

lymphoma, can be made relatively simply. By contrast,

the interpretation of mucosal inflammatory change has

proved to be far more complex. Characterization of

gastrointestinal inflammation has been hampered by

the lack of standard criteria for measuring the histopathological changes within a sample of mucosal tissue.

Over the past two decades, several independent

groups have developed and applied classification systems for characterizing the nature and severity of gastrointestinal inflammatory changes (Jergens et al.,

1992, 1996, 1999, 2003; Wilcock, 1992; Hart et al.,

1994; Yamasaki et al., 1996; Stonehewer et al., 1998;

Baez et al., 1999; German et al., 2000, 2001; Kull

et al., 2001; Zentek et al., 2002; Waly et al., 2004; Peters

et al., 2005; Wiinberg et al., 2005; Münster et al., 2006;

Allenspach et al., 2007; Garcia-Sancho et al., 2007). In

most of these studies, the nature of gastrointestinal inflammation is portrayed primarily by the dominant

population of inflammatory cells (e.g. lymphoplasmacytic, eosinophilic or pyogranulomatous); it is recognized, however, that such populations may overlap

and occur in various combinations. The severity of gastrointestinal inflammation has most often been graded

with a simple four-point scale: normal, mild, moderate

or marked. Although this approach would appear logical, the specific criteria defined by various groups have

differed to the point at which it has become impossible

to relate with certainty the histopathological changes

described in different studies. Even when specific criteria are applied, there may be significant variation between pathologists in the interpretation of changes in

gastrointestinal tissue samples. Thus, Willard et al.

(2002) reported lack of uniformity in the assessment

of 50% of biopsy samples examined by five veterinary

pathologists. This interpretive variation may pose

problems for the routine diagnosis of gastrointestinal

disease or for monitoring the progress of patients receiving post-therapeutic endoscopy. Moreover, such

variation impedes progress in the performance of

multi-centre diagnostic or therapeutic clinical trials

in small animal gastroenterology.

With this background, a Gastrointestinal Standardization Group was convened with the support

of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association

(WSAVA), and with the purpose of developing standards for the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disease in the dog and cat. One of the first tasks of

this group was to develop a set of histopathological

standards for characterizing the nature and severity

of mucosal inflammatory and associated morphological changes. The current monograph presents the outcome of these deliberations, in what we hope will

become an internationally accepted standard for the

description of microscopical changes affecting the mucosa of the canine and feline gastric body, gastric antrum, duodenum and colon.

Materials and Methods

The WSAVA Gastrointestinal Standardization

Group developed the standards presented herein

over several face-to-face meetings (American College

of Veterinary Internal Medicine [ACVIM] Forum,

2004, St Paul; ACVIM Forum, 2005, Baltimore; British Small Animal Veterinary Association [BSAVA]

Congress, 2006, Birmingham; European College of

Veterinary Internal Medicine [ECVIM] Congress,

2006, Amsterdam; ACVIM Forum, 2007, Seattle;

ECVIM Congress, 2007, Budapest) and by electronic

communication in between these meetings. The scope

of the project was first defined by identifying the four

most commonly sampled anatomical regions of the

gastrointestinal mucosa: the gastric body, gastric antrum, duodenum and colon. For each of these regions,

tissue changes were defined by (1) morphological abnormalities, and (2) the major types of inflammatory

cell infiltrating the epithelium and lamina propria of

that region. The Group included in these evaluations

only those microscopical changes considered to be of

greatest relevance to the inflammatory process. Minor

changes that could equally be artefactual (e.g. small

capillary haemorrhage, tissue oedema) were not incorporated into the standards.

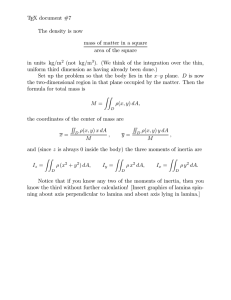

The Group adopted pictorial ‘‘templates’’ of histopathological images to demonstrate the particular

morphological or inflammatory change being presented. It was proposed that for each of these changes,

four images would be presented, namely (1) the normal tissue morphology or baseline numbers of leucocyte subpopulations, (2) mild manifestation, (3)

moderate manifestation, and (4) marked manifestation. The Standardization Group recognized that development of a single pictorial template applicable to

samples taken from both the dog and the cat would be

of greatest value. The fundamental inflammatory

changes that occur within the stomach and intestine

of these two species are in general sufficiently similar

to allow this approach. A major exception, however,

is the density of intraepithelial lymphocytes in the duodenum, which is significantly greater in the cat than

in the dog (German et al., 1999; Waly et al., 2001). It

was agreed that, for this variable, a separate template

would be presented for each species.

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

With these objectives defined, one member of the

Group (MJD) assembled an archive of digital images

by retrospectively screening canine and feline endoscopic biopsy samples from the pathology database at

his institution (Division of Veterinary Pathology, Infection and Immunity, School of Clinical Veterinary

Science, University of Bristol). Images were captured

by a Leica DMLS microscope and associated Leica

DC300 digital camera with IM50 image-management

software. The most representative of these images were

assembled into draft pictorial templates, which were

distributed to the remainder of the group for comment

or replacement by alternative images. By this process

the Group arrived at an agreed set of images, which

now form the basis of the current template.

In addition to developing the pictorial template, the

Group recognized that it would also be useful to

develop a parallel textual description of the key features displayed by each image. This description should

be sufficiently succinct to be applied in the setting of

day-to-day microscopical analysis undertaken by veterinary histopathologists. The aim of the text would

be to complement the image by providing simple

guidelines for assessment and interpretation of each

morphological or inflammatory criterion. These descriptors would be generally based on the ‘‘unit’’ of

a microscopical field examined with a !40 objective,

this being considered the magnification most likely to

be used by diagnostic histopathologists to reach a morphological diagnosis. The proposed text was initially

drafted by MJD and then circulated to the Group

for discussion and editing.

The Group recognized that several studies had

been published in which computer-aided analysis of

immunohistochemically labelled sections had made

possible the precise enumeration of leucocyte subpopulations within the normal canine and feline stomach

and intestine (Roth et al., 1992; Kolbjørnsen et al.,

1994; Jergens et al., 1996, 1999; Elwood et al., 1997;

Stonehewer et al., 1998; German et al., 1999, 2000; Sonea et al., 1999; Roccabianca et al., 2000; Waly et al.,

2001; Paulsen et al., 2003; Southorn, 2004). Although

these data were valuable, they lacked immediate applicability to the simple pictorial template we had

aimed to develop for international use by pathologists

evaluating haematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained sections of gastrointestinal mucosa. However, for completeness we extracted from these data, for inclusion

in the present monograph, key information on tissue

morphology and on leucocyte numbers in lamina

propria and epithelium, derived from HE-stained

and immunohistochemically labelled sections.

The final section of this monograph presents three

standard reporting forms, devised by the Standardization Group for use in parallel with the templates.

S3

The group proposes that pathologists should be

encouraged to examine endoscopic biopsy samples

taken from the alimentary tract in a systematic fashion and to record the major findings by means of a simple ‘‘tick-box’’ format. Accordingly, the three forms

provide for evaluation of samples taken from the

gastric body, gastric antrum, duodenum and colon.

The forms encourage recording of the number of

tissue samples present on the microscope slide and

an assessment of whether these are adequate for interpretive purposes. Samples may be considered entirely

inadequate (and therefore not interpretable), too superficial but still adequate for limited interpretation,

or adequate. The number of tissues considered abnormal is also recorded. The completed forms then make

possible (1) an assessment of the severity of the morphological and inflammatory changes defined by

the templates, and (2) determination of the final morphological diagnosis. Additional space is provided for

further tissue-specific comments.

Results and Supplementary Information

The pictorial and textual templates for assessment of

inflammatory and associated morphological changes

in the gastric body, gastric antrum, duodenum and

colon of the dog and cat are presented in Tables 1e

4. In each case, a single page of this monograph

presents four images associated with one particular

morphological or inflammatory criterion. The first

(uppermost) image shows the expected appearance

of normal tissue, and the remaining images depict

mild, moderate and marked changes. Accompanying

each image is the associated text that verbally defines

the key features shown by the photomicrograph.

The templates presented herein relate to adult animals with fully mature gastrointestinal tracts, which

will most frequently be the subject of clinical endoscopic

examination. Developmental morphology of the canine

and feline gastrointestinal tract has not been investigated extensively, but it is likely that age-related changes

occur. We would therefore caution that some aspects of

the templates presented here may not be directly applicable to samples taken from other age groups.

Additional supplementary information on normal

morphometry and key resident leucocytes derived

from published literature is presented below for each

of the four anatomical regions under consideration.

Gastric Body Mucosa

A single study (Southorn, 2004) characterized the leucocyte subpopulations within the superficial region of the

normal canine gastric body mucosa. A ‘‘mucosal unit’’

was defined by a 250 mm length of mucosa, in which

S4

M.J. Day et al.

the CD3+ intraepithelial lymphocytes (mean 0.93,

range 0e2), CD3+ lamina propria lymphocytes (mean

4.2, range 0.5e13), lamina propria eosinophils

(mean 0.45, range 0e2) and lamina propria plasma

cells (mean 1.59, range 0e5.83) were enumerated.

The samples were derived from eight dogs, in which

considerable inter-animal variation in cell counts occurred.

plasm and express the molecule perforin as shown by

immunohistochemical labelling with cross-reactive antisera (Konno et al., 1994). This observation suggests that

the cells are granular lymphocytes with cytotoxic function. In general, these cells do not appear to increase in

number in feline inflammatory enteropathy, but neoplasia of this lineage is documented (Roccabianca et al.,

2006). Future studies will be needed to clarify the role

of such cells in the intestinal inflammatory response.

Gastric Antral Mucosa

Colonic Mucosa

Again, a single study (Southorn, 2004) characterized

the leucocyte subpopulations within the superficial

region of the normal canine antral mucosa. A ‘‘mucosal unit’’ was defined by a 250-mm length of mucosa,

in which the CD3+ intraepithelial lymphocytes

(mean 4.4, range 1.5e8), CD3+ lamina propria lymphocytes (mean 10.7, range 2.5e16.5), lamina propria eosinophils (mean 2.7, range 0e6) and lamina

propria plasma cells (mean 6.8, range 0.5e15.5)

were enumerated. The samples were derived from

eight dogs, in which considerable inter-animal variation in cell counts occurred.

German et al. (1999, 2000) assessed the number of

goblet cells in normal canine colonic cryptal epithelium (25.6 " 7.32 per 100 colonocytes). However,

the Standardization Group recognizes that measurement of goblet cells in colonic epithelium is not

straightforward and that the number of such cells

may be artefactually reduced by discharge of mucus

content during the biopsy process. For that reason, assessment of alteration in goblet cell number (specifically goblet cell hyperplasia) was not incorporated

into the standard template.

There are, on average, 7.7 " 3.7 intraepithelial

lymphocytes per stretch of 100 colonocytes in the normal canine basal crypt epithelium (German et al.,

1999). In the lamina propria between the basal crypts

of the canine colon there are approximately

5.5 " 4.29 plasma cells and 3.8 " 3.72 eosinophils

per 10,000 mm2 (German et al., 1999, 2000).

Duodenal Mucosa

Several studies have evaluated, morphologically and immunohistochemically, the normal canine and feline duodenal mucosa. The normal villus length for an adult

dog is 722 " 170 mm, the normal crypt depth is

1279 " 203 mm, and the normal villus to crypt ratio is

0.68 " 0.30 (Hart and Kidder, 1978; Hall and Batt,

1990; Paulsen et al., 2003). Normal dogs have a mean

number of 3.6 " 3.56 goblet cells per stretch of 100 villous enterocytes, and 9.3 " 3.09 goblet cells per stretch

of 100 cryptal enterocytes (German et al., 1999). Villous

intraepithelial lymphocytes are less numerous in the

dog (20.6 " 9.5 per 100 enterocytes) than in the cat

(47.8 " 11.7 per 100 enterocytes), but the number of

cryptal intraepithelial lymphocytes in the dog

(5.2 " 2.33 per 100 enterocytes) is similar to that in the

cat (4.6 " 1.7 per 100 enterocytes) (Hall and Batt,

1990; German et al., 1999; Waly et al., 2001). In the

dog, the total leucocyte count is greater in the cryptal

lamina propria (156.3 " 24.91 per 10,000 mm2) than

in the lamina propria of the base (128.3 " 26.64 per

10,000 mm2) or tip (100.7 " 43.89 per 10,000 mm2) of

the villus (German et al., 1999). Similarly, there are

more eosinophils in the canine cryptal lamina propria

(9.8 " 7.51 per 10,000 mm2) than in the lamina propria

of the villus base (3.7 " 3.52 per 10,000 mm2) or tip

(3.8 " 6.06 per 10,000 mm2) (German et al., 1999). In

cats, a population of globular leucocytes is sometimes

recognized within the intestinal epithelium. These cells

have distinctive eosinophilic granules within the cyto-

Discussion

We believe this is the first attempt to create a histopathological standard for the characterization of inflammatory

and associated morphological abnormalities of the stomach, intestine and colon of dogs and cats. The WSAVA

Gastrointestinal Standardization Group presents these

templates in the hope that they will be accepted by our

peers as the current international standard in the definition of inflammatory change in the canine and feline gastrointestinal tract. The group recognizes that simply

producing such a template does not necessarily mean

that its availability will immediately address all of the current problems related to the microscopical interpretation

of endoscopic biopsy samples. The Group encourages

and welcomes the testing of this model in retrospective

and prospective studies of disease.

To test the utility and validity of the template, we are

performing a validation study that will be presented

elsewhere on completion. It is based on the collation

of a large slide set of several hundred endoscopic biopsy

samples derived from the pathology archives of nine institutions in six different countries. These slides have

been coded and reviewed by four pathologist members

of the Standardization Group. Each pathologist has

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

been asked to use the current templates to score the

changes in each biopsy sample and to record these on

the standard reporting forms. These data points have

been entered into a computer spreadsheet and will be

subject to searching statistical analysis, which will

form the basis of subsequent presentations. This analysis may help us to refine further the templates presented

in this monograph.

These templates and reporting forms have been designed to have ready applicability to retrospective or

prospective research investigations, in which a numerical histopathological score may be correlated with

clinical or therapeutic outcome parameters. The

simple numerical addition of grades of histopathological change (where normal ¼ 0, mild ¼ 1, moderate ¼ 2 and marked ¼ 3) may provide an overall

histological score for the tissue of interest.

The WSAVA Gastrointestinal Standardization

Group hopes that the availability of these template

documents will prove of value to clinicians and pathologists working in the field of dog and cat gastroenterology and will facilitate the reporting of microscopical

changes in biopsy samples, reducing variation between

the interpretations of different pathologists and, consequently, between different published studies.

Acknowledgments

The members of the Standardization Group gratefully acknowledge the financial sponsorship from

Hills Pet Nutrition, which has enabled this project

to be undertaken. Although this commercial funding

underpins our efforts, the Group consists entirely of

independent academic scientists and there is no commercial representation. No member of the Group has

declared having personal or research funding from

Hills Pet Nutrition. The group also acknowledges

the support and encouragement of the WSAVA Executive Board and Scientific Advisory Committee. This

monograph has been subject to the normal peerreview process of the Journal of Comparative Pathology.

References

Allenspach, K., Wieland, B., Gröne, A. and Gaschen, F.

(2007). Chronic enteropathies in dogs: evaluation of

risk factors for negative outcome. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 21, 700e708.

Baez, J. L., Hendrick, M. J., Walker, L. M. and

Washabau, R. J. (1999). Radiographic, ultrasonographic, and endoscopic findings in cats with inflammatory bowel disease of the stomach and small intestine: 33

cases (1990e1997). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 215, 349e354.

S5

Elwood, C. M., Hamblin, A. S. and Batt, R. M. (1997).

Quantitative and qualitative immunohistochemistry of

T cell subsets and MHC Class II expression in the canine small intestine. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 58, 195e207.

Garcia-Sancho, M., Rodriguez-Franco, F., Sainz, A.,

Mancho, C. and Rodriguez, A. (2007). Evaluation of

clinical, macroscopic, and histopathologic response to

treatment in nonhypoproteinemic dogs with lymphoplasmacytic enteritis. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 21, 11e17.

German, A. J., Hall, E. J. and Day, M. J. (1999). Analysis

of leucocyte subsets in the canine intestine. Journal of

Comparative Pathology, 120, 129e145.

German, A. J., Hall, E. J., Kelly, D. F., Watson, A. D. and

Day, M. J. (2000). An immunohistochemical study of

histiocytic ulcerative colitis in boxer dogs. Journal of

Comparative Pathology, 122, 163e175.

German, A. J., Hall, E. J. and Day, M. J. (2001). Characterization of immune cell populations within the duodenal mucosa of dogs with enteropathies. Journal of

Veterinary Internal Medicine, 15, 14e25.

Hall, E. J. and Batt, R. M. (1990). Development of wheatsensitive enteropathy in Irish Setters: morphologic changes.

American Journal of Veterinary Research, 51, 978e982.

Hart, I. R. and Kidder, D. E. (1978). The quantitative assessment of normal canine small intestinal mucosa. Research in Veterinary Science, 25, 157e162.

Hart, J. R., Shaker, E., Patnaik, A. K. and Garvey, M. S.

(1994). Lymphocytic-plasmacytic enterocolitis in cats:

60 cases (1988e1990). Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 30, 505e514.

Jergens, A. E., Moore, F. M., Haynes, J. S. and Miles, K. G.

(1992). Idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease in dogs

and cats: 84 cases (1987e1990). Journal of the American

Veterinary Medical Association, 201, 1603e1608.

Jergens, A. E., Moore, F. M., Kaiser, M. S., Haynes, J. S.

and Kinyon, J. M. (1996). Morphometric evaluation of

immunoglobulin A-containing and immunoglobulin Gcontaining cells and T cells in duodenal mucosa from

healthy dogs and from dogs with inflammatory bowel

disease or nonspecific gastroenteritis. American Journal

of Veterinary Research, 57, 697e704.

Jergens, A. E., Gamet, Y., Moore, F. M., Niyo, Y., Tsao, C.

and Smith, B. (1999). Colonic lymphocyte and plasma

cell populations in dogs with lymphocytic-plasmacytic colitis. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 60, 515e520.

Jergens, A. E., Schreiner, C. A., Frank, D. E., Niyo, Y.,

Ahrens, F. E., Eckersall, P. D., Benson, T. J. and

Evans, R. (2003). A scoring index for disease activity

in canine inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 17, 291e297.

Kolbjørnsen, Ø., Press, C. M., Moore, P. F. and

Landsverk, T. (1994). Lymphoid follicles in the gastric

mucosa of dogs. Distribution and lymphocyte phenotypes. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 40,

299e312.

Konno, A., Hashimoto, Y., Kon, Y. and Sugimura, M.

(1994). Perforin-like immunoreactivity in feline globule

S6

M.J. Day et al.

leukocytes and their distribution. Journal of Veterinary

Medical Science, 56, 1101e1105.

Kull, P. A., Hess, R. S., Craig, L. E., Saunders, H. M. and

Washabau, R. J. (2001). Clinical, clinicopathologic,

radiographic, and ultrasonographic characteristics of

intestinal lymphangiectasia in dogs: 17 cases (1996e

1998). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 219, 197e202.

Münster, M., Hörauf, A. and Bilzer, T. (2006). Assessment

of disease severity and outcome of dietary, antibiotic,

and immunosuppressive interventions by use of the canine IBD activity index in 21 dogs with inflammatory

bowel disease. Berliner und Münchener Tierärztliche

Wochenschrift (Berlin), 119, 493e505.

Paulsen, D. B., Buddington, K. K. and Buddington, R. K.

(2003). Dimensions and histologic characteristics of the

small intestine of dogs during postnatal development.

American Journal of Veterinary Research, 64, 618e626.

Peters, I. R., Helps, C. R., Calvert, E. L., Hall, E. J. and

Day, M. J. (2005). Cytokine mRNA quantification in

duodenal mucosa from dogs with chronic enteropathies

by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 19, 644e653.

Roccabianca, P., Woo, J. C. and Moore, P. F. (2000).

Characterization of the diffuse mucosal associated lymphoid tissue of feline small intestine. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 75, 27e42.

Roccabianca, P., Vernau, W., Caniatti, M. and

Moore, P. F. (2006). Feline large granular lymphocyte

(LGL) lymphoma with secondary leukemia: primary intestinal origin with predominance of a CD3/CD8aa

phenotype. Veterinary Pathology, 43, 15e28.

Roth, L., Walton, A. M. and Leib, M. S. (1992). Plasma

cell populations in the colonic mucosa of clinically normal dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 28, 39e42.

Sonea, I. M., Harkins, K., Wannemuehler, M. J.,

Jergens, A. E., Merten, E. A., Sacco, R. E. and

Cunnick, J. E. (1999). Flow cytometric analysis of canine colonic mucosal lymphocytes from endoscopically

obtained biopsy specimens. American Journal of Veterinary

Research, 60, 346e353.

Southorn, E. P. (2004). An improved approach to the

histologic assessment of canine chronic gastritis. DVSc

thesis, University of Guelph.

Stonehewer, J., Simpson, J. W., Else, R. W. and

Macintyre, N. (1998). Evaluation of B and T lymphocytes and plasma cells in colonic mucosa from healthy

dogs and from dogs with inflammatory bowel disease.

Research in Veterinary Science, 65, 59e63.

Waly, N., Gruffydd-Jones, T. J., Stokes, C. R. and

Day, M. J. (2001). The distribution of leucocyte subsets

in the small intestine of normal cats. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 124, 172e182.

Waly, N. E., Stokes, C. R., Gruffydd-Jones, T. J. and

Day, M. J. (2004). Immune cell populations in the duodenal mucosa of cats with inflammatory bowel disease.

Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 18, 816e825.

Wiinberg, B., Spohr, A., Dietz, H. H., Egelund, T.,

Greiter-Wilke, A., McDonough, S. P., Olsen, J.,

Priestnall, S., Chang, Y. F. and Simpson, K. W.

(2005). Quantitative analysis of inflammatory and immune responses in dogs with gastritis and their relationship to Helicobacter spp. infection. Journal of Veterinary

Internal Medicine, 19, 4e14.

Wilcock, B. (1992). Endoscopic biopsy interpretation in canine and feline enterocolitis. Seminars in Veterinary Medicine and Surgery (Small Animal), 7, 162e171.

Willard, M. D., Lovering, S. L., Cohen, N. D. and

Weeks, B. R. (2001). Quality of tissue specimens obtained endoscopically from the duodenum of dogs and

cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association,

219, 474e479.

Willard, M. D., Jergens, A. E., Duncan, R. B.,

Leib, M. S., McCracken, M. D., DeNovo, R.,

Helman, R. G., Slater, M. R. and Harbison, J. L.

(2002). Interobserver variation among histopathologic

evaluations of intestinal tissues from dogs and cats.

Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association,

220, 1177e1182.

Yamasaki, K., Suematsu, H. and Takahashi, T. (1996).

Comparison of gastric and duodenal lesions in dogs

and cats with and without lymphocytic-plasmacytic enteritis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 209, 93e97.

Zentek, J., Hall, E. J., German, A. J., Haverson, K.,

Bailey, M., Rolfe, V., Butterwick, R. and Day, M. J.

(2002). Morphology and immunopathology of

the small and large intestine in dogs with non-specific dietary sensitivity. Journal of Nutrition, 132, 1652Se1654S.

S7

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 1

Histopathological standards for inflammation of the gastric body

Surface epithelial injury

Normal surface epithelium

Single layer of columnar epithelium. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Mild surface epithelial injury

Attenuation, degeneration, vacuolation or separation of focal

areas of superficial epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate surface epithelial injury

More pronounced degenerative changes with focal loss of

some epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked surface epithelial injury

Widespread ulceration of surface epithelium. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S8

M.J. Day et al.

Table 1 (continued)

Gastric pit epithelial injury

Normal epithelium

Single layer of columnar epithelium in neck of gastric pit. HE.

Bar, 50 µm.

Mild epithelial injury

Attenuation, degeneration, vacuolation or separation of focal

areas of epithelium of the gastric pit (within area indicated).

HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate epithelial injury

More pronounced degenerative changes, with focal loss of

some epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked epithelial injury

Widespread disruption and loss of the epithelial structure of

the gastric pit. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

S9

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 1 (continued)

Fibrosis/glandular nesting/mucosal atrophy

Normal mucosa

Glandular tissue closely packed but separated by narrow bands

of connective tissue, 1–2 fibrocytes in width. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild mucosal atrophy

Glands individualized and separated by broader bands of

connective tissue, up to 5 fibrocytes in width. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate mucosal atrophy

Variably sized lobules of glandular tissue isolated (“nested”)

within connective tissue, separated by matrix up to 10

fibrocytes in width. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked mucosal atrophy

Nested, atrophic and sparse lobules of glandular tissue

separated by collagenous matrix-filled spaces >10 fibrocytes in

width. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S10

M.J. Day et al.

Table 1 (continued)

Intraepithelial lymphocytes

Normal intraepithelial lymphocytes

Sparse population of approximately 1–2 cells per stretch of 50

epithelial cells. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Mild increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Individual lymphocytes, up to 10 per stretch of 50 epithelial

cells. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Lymphocytes may cluster in groups of up to 4 cells. There may

be up to 20 per stretch of 50 epithelial cells. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Epithelium is more diffusely infiltrated by lymphocytes (up to

50 per stretch of 50 epithelial cells). HE. Bar, 200 µm.

S11

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 1 (continued)

Lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma cells*

Normal mucosa

Sparse individual lymphocytes and plasma cells beneath

surface epithelium and between glands; <20 cells per ×40 field.

HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells beneath

epithelium and between glands; 20–50 cells per ×40 field.HE.

Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells present in lamina

and may infiltrate glands; 50–100 cells per ×40 field. HE.

Bar, 200 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Diffuse infiltrate of cells occupies much of the area of lamina

propria and may infiltrate and disrupt glandular structure;

>100 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S12

M.J. Day et al.

Table 1 (continued)

Lamina propria eosinophils*

Normal mucosa

One or two eosinophils per ×40 field within lamina propria are

normal. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal eosinophils

Clusters of eosinophils within lamina propria; up to 20 cells

per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal eosinophils

More widespread infiltration of eosinophils within lamina

propria; up to 50 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal eosinophils

Diffuse infiltration of lamina propria and sometimes glandular

structure; up to 100 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

S13

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 1 (continued)

Lamina propria neutrophils

Normal mucosa

Neutrophils should not be present. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal neutrophils

Scattered neutrophils within superficial lamina propria; 10–20

cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal neutrophils

More widespread infiltration by neutrophils within lamina

propria; up to 50 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal neutrophils

Diffuse infiltration of lamina propria and sometimes glands; up

to 100 cells per ×40 field. There may be a concurrent

macrophage infiltrate. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S14

M.J. Day et al.

Table 1 (continued)

Gastric lymphofollicular hyperplasia

Normal mucosa

Small lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying <10% of

biopsy area are normal, usually in the deep mucosa. HE. Bar,

1 mm.

Mild hyperplasia

Lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying 10–30% of biopsy

area. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

Moderate hyperplasia

Lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying 30–50% of biopsy

area. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

Marked hyperplasia

Lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying >50% of biopsy

area. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

*Mixed inflammatory responses showing both lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic infiltration are not uncommon.

S15

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 2

Histopathological standards for inflammation of the gastric antrum

Epithelial injury

Normal mucosa

Single layer of columnar epithelium over surface and lining

gastric pits. Deep tubular pyloric mucous glands. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

Mild epithelial injury

Attenuation, degeneration or vacuolation of focal areas of

superficial epithelium. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate epithelial injury

More marked degenerative changes, with focal detachment or

loss of some epithelium. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked epithelial injury

Widespread ulceration of surface epithelium. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S16

M.J. Day et al.

Table 2 (continued)

Epithelial hyperplasia

Normal mucosa

Single layer of columnar epithelium over surface and lining

gastric pits. Deep tubular pyloric mucous glands. HE. Bar,

200 µm.

Mild epithelial hyperplasia

Uniform increased thickness of gastric pit epithelial lining.

Mild dilation of pit lumen, with some folding of epithelium.

HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Moderate epithelial hyperplasia

Increased thickness of gastric pit epithelial lining, with

distortion and variation in pits. Dilation and folding of

epithelium. Epithelium may be more basophilic. HE. Bar,

500 µm.

Marked epithelial hyperplasia

This change was recognized as an uncommon accompaniment

to inflammatory change and no image or descriptor was

prepared.

S17

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 2 (continued)

Mucosal fibrosis/glandular atrophy

Normal mucosa

Gastric pits and glands uniformly arranged and separated by

bands of connective tissue, up to 10 fibrocytes in width. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

Mild mucosal atrophy

Gastric pits separated by broader bands of connective tissue.

Mucous glands individualized by narrow but distinct

connective tissue bands. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Moderate mucosal atrophy

Gastric pits separated by broader bands of connective tissue.

Mucous gland acini reduced in number and more widely

separated by connective tissue. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Marked mucosal atrophy

Atrophic and sparse lobules of gastric pit/glandular tissue

nested within a more extensive collagenous matrix. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S18

M.J. Day et al.

Table 2 (continued)

Intraepithelial lymphocytes

Normal mucosa

Sparse population of approximately 1–2 cells per stretch of 50

epithelial cells. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Individual lymphocytes, up to 5 per stretch of 50 epithelial

cells. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Individual lymphocytes, up to 10 per stretch of 50 epithelial

cells. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Individual or small clusters of lymphocytes, up to 20 per 50

epithelial cells. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

S19

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 2 (continued)

Lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma cells*

Normal mucosa

Scattered individual lymphocytes and plasma cells beneath

surface epithelium and between gastric pits; <20 cells per ×40

field. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells beneath

epithelium and between gastric pits; 20–50 cells per ×40 field.

HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells in lamina may

separate gastric pits; 50–100 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Diffuse infiltration of cells occupies much of the area of lamina

propria and may infiltrate and disrupt gastric pit structure;

>100 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S20

M.J. Day et al.

Table 2 (continued)

Lamina propria eosinophils

*

Normal mucosa

Generally no eosinophils within lamina propria. Up to 1–2 per

×40 field considered normal. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal eosinophils

Clusters of eosinophils within lamina propria; up to 10 cells

per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal eosinophils

More widespread infiltration of eosinophils within lamina

propria; up to 50 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal eosinophils

Diffuse infiltration of lamina propria, which may distort gastric

pit structure; up to 100 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

S21

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 2 (continued)

Lamina propria neutrophils

Normal mucosa

Should be none present. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal neutrophils

Scattered neutrophils within superficial lamina propria; up to

10–20 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal neutrophils

More widespread infiltration of neutrophils within lamina

propria; up to 50 cells per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal neutrophils

Diffuse infiltration of lamina propria, which may distort gastric

pit structure; up to 100 cells per ×40 field. There may be a

concurrent macrophage infiltrate. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S22

M.J. Day et al.

Table 2 (continued)

Gastric lymphofollicular hyperplasia

Normal mucosa

Small lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying <5% of

biopsy area are normal, usually in the deep mucosa. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

Mild lymphofollicular hyperplasia

Lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying up to10% of biopsy

area. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

Moderate lymphofollicular hyperplasia

Lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying up to 25% of

biopsy area. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

Marked lymphofollicular hyperplasia

Lymphoid aggregates or follicles occupying up to 50% of

biopsy area. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

*Mixed inflammatory responses showing both lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic inflammation are not uncommon.

S23

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 3

Histopathological standards for inflammation of the duodenum

Villous stunting

Normal mucosa

Long, slender uniform villi when sectioned longitudinally.

Note that the accurate assessment of villous height is only

possible with well-oriented endoscopic biopsy samples. HE.

Bar, 1 mm.

Mild villous stunting

Villi reduced to approximately 75% of normal length; some

may be increased in width and non-uniform. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

Moderate villous stunting

Villi reduced to approximately 50% of normal length

(stunted); most are increased in width and some may be fused.

HE. Bar, 1 mm.

Marked villous stunting

Villi reduced to <25% of normal length and often fused;

intestinal surface may be flat in severe cases. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

(Continued on next page)

S24

M.J. Day et al.

Table 3 (continued)

Villous epithelial injury

Normal mucosa

Single layer of columnar epithelium. In dogs, normal number

of goblet cells is approximately 3 per 100 enterocytes. HE.

Bar, 50 µm.

Mild villous epithelial injury

Attenuation, degeneration, vacuolation or separation of focal

areas of superficial epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate villous epithelial injury

More marked degenerative changes, with focal loss of some

epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked villous epithelial injury

Widespread ulceration of surface epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

S25

Table 3 (continued)

Crypt distension

Normal mucosa

Uniform crypts aligned perpendicularly to surface, with narrow

luminal area. Columnar epithelial lining with occasional

goblet cells (normal in dog is approximately 9 per 100

enterocytes). Dilation or “abscessation” of individual crypts is

within normal limits. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild crypt distension

Up to 10% of crypts in section are dilated, distorted or contain

luminal eosinophilic material/degenerate neutrophils (“crypt

abscess”). HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate crypt distension

Up to 25% of crypts in section are dilated, distorted or present

as crypt abscesses. HE. Bar, 1 mm.

Marked crypt distension

Up to 50% of crypts in section are dilated, distorted or present

as crypt abscesses. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S26

M.J. Day et al.

Table 3 (continued)

Lacteal dilation

Normal mucosa

Central lacteal represents up to approximately 25% of width of

the villous lamina propria when sectioned longitudinally. HE.

Bar, 200 µm.

Mild lacteal dilation

Central lacteal represents up to approximately 50% of width of

the villous lamina propria when sectioned longitudinally. Villi

are generally wider than normal. HE. Bar, 1 µm.

Moderate lacteal dilation

Central lacteal ballooned, representing up to 75% of width of

the villous lamina propria when sectioned longitudinally.

Affected villi are wider than normal. HE. Bar, 1 µm.

Marked lacteal dilation

Central lacteal markedly dilated to occupy up to 100% of the

villous lamina propria. Surrounding lamina propria (where

apparent) is oedematous. Villi are markedly distended –

particularly at tips, giving a “club-shaped” appearance. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

S27

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 3 (continued)

Mucosal fibrosis

Normal mucosa

Narrow band of stroma, up to 1 to 2 fibroblasts in width,

separates crypts. HE. Bar, 100 µm.

Mild mucosal fibrosis

Crypts separated by a band of stroma, up to 5 fibroblasts in

width. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate mucosal fibrosis

Crypts separated by a band of stroma, up to 10 fibroblasts in

width. Crypts may vary inwidth, some being atrophic. HE.

Bar, 200 µm.

Marked mucosal fibrosis

Crypts separated by an extensive area of collagenous matrix,

>10 fibroblasts in width. Crypts may be atrophic or lost and

replaced by fibrotic matrix. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S28

M.J. Day et al.

Table 3 (continued)

Canine intraepithelial lymphocytes

Normal mucosa

Normal number in villus, approximately 5–10 per ×40 stretch

of epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Mild increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Mild increase in number equates to approximately 20–30 per

×40 stretch of villous epithelium. These will generally be

individual cells. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Approximately 30–50 per ×40 stretch of villous epithelium.

These may be focally clustered. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Approximately 50–100 per ×40 stretch of villous epithelium.

These may be clustered and occur at all levels of the

epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

S29

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 3 (continued)

Feline intraepithelial lymphocytes

Normal mucosa

Normal number in villus is approximately 10 – 20 per ×40

stretch of epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Mild increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Approximately 40 – 60 per ×40 stretch of villous epithelium.

These will generally be individual cells. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Approximately 60 – 100 per ×40 stretch of villous epithelium.

These may be focally clustered. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes

Approximately >100 per ×40 stretch of villous epithelium.

These may be clustered at all levels of the epithelium. HE.

Bar, 50 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S30

M.J. Day et al.

Table 3 (continued)

Text

Lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma cells*

Normal mucosa

Within the villous lamina propria, approximately 25% of the

area of one ×40 field may be occupied by lymphocytes and

plasma cells. Between crypts, there may be 1–2 lymphocytes or

plasma cells. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lymphocytes and plasma cells may occupy 25–50% of the area

of the villous lamina propria in a ×40 field. Crypts may be

separated by up to 5 lymphocytes or plasma cells. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma

cells

Lymphocytes and plasma cells may occupy 50–75% of the

villous lamina propria in a ×40 field. Crypts may be separated

by up to 10 lymphocytes or plasma cells. HE. Bar, 100 µm.

Marked increase in lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma

cells

Lymphocytes and plasma cells may occupy 75 - 100% of the

villous lamina propria in a ×40 field. Crypts may be separated

by up to 20 lymphocytes and plasma cells. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

S31

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 3 (continued)

Lamina propria eosinophils*

Normal mucosa

Normal number of eosinophils may approximate 2–3 cells per

×40 field. Eosinophils may be more numerous in young animals.

HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Mild increase in lamina propria eosinophils

Mild elevation in number of eosinophils to approximately

5 − 10 per ×40 field. Mononuclear cells still dominate the tissue

population of leucocytes. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in lamina propria eosinophils

Moderate elevation to 10 - 20 per ×40 field. Mononuclear cells

still dominate the tissue population of leucocytes or may occur

in a number similar to that of the eosinophils. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in lamina propria eosinophils

Eosinophils dominate the tissue population of leucocytes and

are not easily enumerated within a ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S32

M.J. Day et al.

Table 3 (continued)

Lamina propria neutrophils

Normal mucosa

Neutrophils should not be present. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Mild increase in lamina propria neutrophils

Mild infiltrate (5 – 10 neutrophils per ×40 field) in lamina

propria may spread into epithelium. Mononuclear cells still

dominate. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in lamina propria neutrophils

Moderate infiltrate (20 – 30 neutrophils per ×40 field); may be

accompanied by macrophages. Neutrophils and mononuclear

cells may be present in equal numbers. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in lamina propria neutrophils

Neutrophils are the dominant population in a ×40 field and

are not easily enumerated. May be accompanied by

macrophages. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

*Mixed inflammatory responses showing both lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic inflammation are not uncommon.

S33

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 4

Histopathological standards for inflammation of the colon

Surface epithelial injury

Normal mucosa

Single layer of columnar epithelium over surface and lining

crypts. Goblet cells within surface epithelium. More goblet

cells in crypt lining. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild surface epithelial injury

Attenuation, degeneration or vacuolation of focal areas of

superficial epithelium. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate surface epithelial injury

More marked degenerative changes, with focal separation and

loss of some epithelium. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked surface epithelial injury

Widespread ulceration of surface epithelium. HE. Bar, 100 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S34

M.J. Day et al.

Table 4 (continued)

Crypt hyperplasia

Normal colon

Crypts of uniform length, diameter and perpendicular

arrangement. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Mild crypt hyperplasia

Crypt lining more basophilic and thickened (particularly

basally), resulting in mild distortion and lack of uniformity. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

Moderate crypt hyperplasia

Crypt lining diffusely thickened, sometimes resulting in

increased width of crypts, with mild distortion. May be some

folding of lining epithelium into lumen of crypt. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Marked crypt hyperplasia

Crypt lining markedly thickened; may appear multilayered and

basophilic. Associated with crypt dilation and distortion.HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

S35

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 4 (continued)

Crypt dilation and distortion

Normal mucosa

Crypts of uniform length, diameter and perpendicular

arrangement. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Mild crypt dilation and distortion

Crypts generally perpendicular but of increased diameter, with

more prominent lumen. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Moderate crypt dilation and distortion

Crypts irregularly oriented and may be branching. Increased

diameter, with prominent lumen. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked crypt dilation and distortion

Crypts widely dilated and distorted, with no normal

perpendicular orientation. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S36

M.J. Day et al.

Table 4 (continued)

Mucosal fibrosis and atrophy

Normal colon

Narrow band of stroma separates crypts uniformly. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

Mild mucosal fibrosis and atrophy

Crypts separated by wider band of stroma, or crypt structure

focally disrupted by localized zone of mild fibrosis. HE.

Bar, 500 µm.

Moderate mucosal fibrosis and atrophy

Loss of crypts. Surviving atrophic crypts are seen within a

prominent collagenous matrix that replaces much of the

mucosal architecture. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Marked mucosal fibrosis and atrophy

More extensive fibrosis, with almost complete loss of cryptal

structure. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

S37

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 4 (continued)

Lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma cells*

Normal colon

Lymphocytes and plasma cells in lamina propria between

crypts. Five or fewer cells are regarded as normal. Scattered

individual intraepithelial lymphocytes are present in surface

and cryptal epithelium. Increase in the number of

intraepithelial lymphocytes appears to be a rare change in the

colon. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lymphocytes and plasma cells may fill inter-cryptal region and

mildly increase separation of crypts, but they do not disrupt

normal perpendicular cryptal architecture. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lymphocytes and plasma cells fill inter-cryptal region and

moderately increase separation of crypts. May cause some

distortion of cryptal architecture. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lymphocytes and plasma cells are diffusely distributed in the

lamina propria, disrupting, distorting or obliterating cryptal

micro-architecture. HE. Bar, 500 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S38

M.J. Day et al.

Table 4 (continued)

Superficial lamina propria eosinophils*

Normal colon

One or two scattered eosinophils may be present per ×40 field

of superficial lamina propria. HE. Bar, 100 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal eosinophils

Mild elevation in number of eosinophils to approximately

5 – 10 per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal eosinophils

Moderate elevation to 10 - 20 per ×40 field. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal eosinophils

Eosinophils dominate the tissue population of leucocytes and

are not easily enumerated within a ×40 field. HE. Bar, 100 µm.

S39

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

Table 4 (continued)

Lamina propria neutrophils

Normal colon

Neutrophils should not be present. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal neutrophils

Mild infiltrate (5 – 10 neutrophils per ×40 field) in lamina

propria or spreading into epithelium. Mononuclear cells still

dominate. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal neutrophils

Moderate infiltrate may be 20 – 30 neutrophils per ×40 field;

may be accompanied by macrophages. Neutrophils may be

equal in number to mononuclear cells. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal neutrophils

Neutrophils are the dominant population in a ×40 field and

are not easily enumerated. May be accompanied by

macrophages. HE. Bar, 50 µm.

(Continued on next page)

S40

M.J. Day et al.

Table 4 (continued)

Lamina propria macrophages

Normal colon

Occasional scattered macrophages within lamina propria. HE.

Bar, 200 µm.

Mild increase in mucosal macrophages

Macrophages increased in number (up to 20 per ×40 field)

and may form small clusters. HE. Bar, 100 µm.

Moderate increase in mucosal macrophages

Macrophages increased in number (up to 50 per ×40 field)

and may focally aggregate. HE. Bar, 100 µm.

Marked increase in mucosal macrophages

Macrophages are dominant population, forming a diffuse

sheet of cells within the lamina propria and displacing cryptal

microarchitecture. HE. Bar, 200 µm.

*Mixed inflammatory responses showing both lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic inflammation are not uncommon.

S41

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

STANDARD FORM FOR ASSESSMENT OF THE

GASTRIC BODY OR ANTRAL MUCOSA

Pathologist_______________________

Case number_____________________

Number of pieces of gastric tissue on slide_________

Tissue present

Inadequate

Too superficial

Adequate depth

Number of tissues abnormal______________

MORPHOLOGICAL FEATURES

Normal

Mild

Surface epithelial injury

Gastric pit epithelial injury

Fibrosis/glandular nesting/

mucosal atrophy

INFLAMMATION

Intraepithelial lymphocytes

Lamina propria

lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lamina propria eosinophils

Lamina propria neutrophils

Other inflammatory cells

Gastric lymphofollicular hyperplasia

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Normal tissue

Lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory

Eosinophilic inflammatory

Neutrophilic inflammatory

Mucosal atrophy/fibrosis (non-inflammatory)

Other

OTHER COMMENTS

Moderate

Marked

S42

M.J. Day et al.

STANDARD FORM FOR ASSESSMENT OF DUODENAL MUCOSA

Pathologist_______________________

Case number_____________________

Number of pieces of duodenal tissue on slide_________

Tissue present

Inadequate

Too superficial

Adequate depth

Number of tissues abnormal______________

MORPHOLOGICAL FEATURES

Normal

Mild

Villous stunting

Epithelial injury

Crypt distension

Lacteal dilation

Mucosal fibrosis

INFLAMMATION

Intraepithelial lymphocytes

Lamina propria

lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lamina propria eosinophils

Lamina propria neutrophils

Other

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Normal tissue

Lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory

Eosinophilic inflammatory

Neutrophilic inflammatory

Lymphangiectasia

Mucosal atrophy/fibrosis (non-inflammatory)

Other

OTHER COMMENTS

Moderate Marked

Gastrointestinal Histopathology Standards

STANDARD FORM FOR ASSESSMENT OF COLONIC MUCOSA

Pathologist_______________________

Case number_____________________

Number of pieces of colonic tissue on slide_________

Tissue present

Inadequate

Too superficial

Adequate depth

Number of colonic tissues abnormal______________

MORPHOLOGICAL FEATURES

Normal

Mild

Surface epithelial injury

Crypt hyperplasia

Crypt dilation/distortion

Fibrosis/atrophy

INFLAMMATION

Lamina propria

lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lamina propria eosinophils

Lamina propria neutrophils

Lamina propria macrophages

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Normal colon

Lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory

Eosinophilic inflammatory

Neutrophilic inflammatory

Histiocytic/granulomatous inflammatory

Mucosal atrophy/fibrosis (non-inflammatory)

Other

OTHER COMMENTS

Moderate Marked

S43