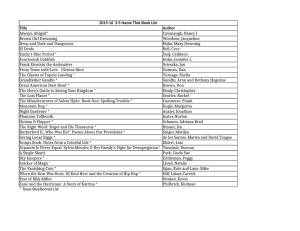

Mahatma Gandhi, byname of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, (born October

2, 1869, Porbandar, India—died January 30, 1948, Delhi), Indian lawyer, politician,

social activist, and writer who became the leader of the nationalist movement against

the British rule of India. As such, he came to be considered the father of

his country. Gandhi is internationally esteemed for his doctrine of nonviolent

protest (satyagraha) to achieve political and social progress.

In the eyes of millions of his fellow Indians, Gandhi was the Mahatma (“Great Soul”).

The unthinking adoration of the huge crowds that gathered to see him all along the

route of his tours made them a severe ordeal; he could hardly work during the day or

rest at night. “The woes of the Mahatmas,” he wrote, “are known only to the

Mahatmas.” His fame spread worldwide during his lifetime and only increased after

his death. The name Mahatma Gandhi is now one of the most universally recognized

on earth.

Youth

Gandhi was the youngest child of his father’s fourth wife. His father—Karamchand

Gandhi, who was the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar, the capital of a small

principality in western India (in what is now Gujarat state) under British

suzerainty—did not have much in the way of a formal education. He was, however, an

able administrator who knew how to steer his way between the capricious princes,

their long-suffering subjects, and the headstrong British political officers in power.

Gandhi’s mother, Putlibai, was completely absorbed in religion, did not care much

for finery or jewelry, divided her time between her home and the temple, fasted

frequently, and wore herself out in days and nights of nursing whenever there was

sickness in the family. Mohandas grew up in a home steeped in Vaishnavism—

worship of the Hindu god Vishnu—with a strong tinge of Jainism, a morally rigorous

Indian religion whose chief tenets are nonviolence and the belief that everything in

the universe is eternal. Thus, he took for granted ahimsa (noninjury to all living

beings), vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and mutual tolerance between

adherents of various creeds and sects.

The educational facilities at Porbandar were rudimentary; in the primary school that

Mohandas attended, the children wrote the alphabet in the dust with their fingers.

Luckily for him, his father became dewan of Rajkot, another princely state. Though

Mohandas occasionally won prizes and scholarships at the local schools, his record

was on the whole mediocre. One of the terminal reports rated him as “good at

English, fair in Arithmetic and weak in Geography; conduct very good, bad

handwriting.” He was married at the age of 13 and thus lost a year at school.

A diffident child, he shone neither in the classroom nor on the playing field. He loved

to go out on long solitary walks when he was not nursing his by then ailing father

(who died soon thereafter) or helping his mother with her household chores.

He had learned, in his words, “to carry out the orders of the elders, not to scan

them.” With such extreme passivity, it is not surprising that he should have gone

through a phase of adolescent rebellion, marked by secret atheism, petty thefts,

furtive smoking, and—most shocking of all for a boy born in a Vaishnava family—

meat eating. His adolescence was probably no stormier than that of most children of

his age and class. What was extraordinary was the way his youthful transgressions

ended.

“Never again” was his promise to himself after each escapade. And he kept his

promise. Beneath an unprepossessing exterior, he concealed a burning passion for

self-improvement that led him to take even the heroes of Hindu mythology, such

as Prahlada and Harishcandra—legendary embodiments of truthfulness and

sacrifice—as living models.

In 1887 Mohandas scraped through the matriculation examination of the University

of Bombay (now University of Mumbai) and joined Samaldas College

in Bhavnagar (Bhaunagar). As he had to suddenly switch from his native language—

Gujarati—to English, he found it rather difficult to follow the lectures.

Meanwhile, his family was debating his future. Left to himself, he would have liked to

have been a doctor. But, besides the Vaishnava prejudice against vivisection, it was

clear that, if he was to keep up the family tradition of holding high office in one of the

states in Gujarat, he would have to qualify as a barrister. That meant a visit

to England, and Mohandas, who was not too happy at Samaldas College, jumped at

the proposal. His youthful imagination conceived England as “a land of philosophers

and poets, the very centre of civilization.” But there were several hurdles to be

crossed before the visit to England could be realized. His father had left the family

little property; moreover, his mother was reluctant to expose her youngest child to

unknown temptations and dangers in a distant land. But Mohandas was determined

to visit England. One of his brothers raised the necessary money, and his mother’s

doubts were allayed when he took a vow that, while away from home, he would not

touch wine, women, or meat. Mohandas disregarded the last obstacle—the decree of

the leaders of the Modh Bania subcaste (Vaishya caste), to which the Gandhis

belonged, who forbade his trip to England as a violation of the Hindu religion—and

sailed in September 1888. Ten days after his arrival, he joined the Inner Temple, one

of the four London law colleges (The Temple).

Sojourn in England and return to

India of Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi took his studies seriously and tried to brush up on his English and Latin by

taking the University of London matriculation examination. But, during the three

years he spent in England, his main preoccupation was with personal

and moral issues rather than with academic ambitions. The transition from the halfrural atmosphere of Rajkot to the cosmopolitan life of London was not easy for him.

As he struggled painfully to adapt himself to Western food, dress, and etiquette, he

felt awkward. His vegetarianism became a continual source of embarrassment to

him; his friends warned him that it would wreck his studies as well as his health.

Fortunately for him he came across a vegetarian restaurant as well as a book

providing a reasoned defense of vegetarianism, which henceforth became a matter

of conviction for him, not merely a legacy of his Vaishnava background. The

missionary zeal he developed for vegetarianism helped to draw the pitifully shy youth

out of his shell and gave him a new poise. He became a member of the executive

committee of the London Vegetarian Society, attending its conferences and

contributing articles to its journal.

In the boardinghouses and vegetarian restaurants of England, Gandhi met not only

food faddists but some earnest men and women to whom he owed his introduction to

the Bible and, more important, the Bhagavadgita, which he read for the first time in

its English translation by Sir Edwin Arnold. The Bhagavadgita (commonly known as

the Gita) is part of the great epic the Mahabharata and, in the form of a

philosophical poem, is the most-popular expression of Hinduism. The English

vegetarians were a motley crowd. They included socialists and humanitarians such

as Edward Carpenter, “the British Thoreau”; Fabians such as George Bernard Shaw;

and Theosophists such as Annie Besant. Most of them were idealists; quite a few

were rebels who rejected the prevailing values of the late-Victorian establishment,

denounced the evils of the capitalist and industrial society, preached the cult of the

simple life, and stressed the superiority of moral over material values and of

cooperation over conflict. Those ideas were to contribute substantially to the shaping

of Gandhi’s personality and, eventually, to his politics.

Painful surprises were in store for Gandhi when he returned to India in July 1891.

His mother had died in his absence, and he discovered to his dismay that

the barrister’s degree was not a guarantee of a lucrative career. The legal

profession was already beginning to be overcrowded, and Gandhi was much

too diffident to elbow his way into it. In the very first brief he argued in a court in

Bombay (now Mumbai), he cut a sorry figure. Turned down even for the part-time

job of a teacher in a Bombay high school, he returned to Rajkot to make a modest

living by drafting petitions for litigants. Even that employment was closed to him

when he incurred the displeasure of a local British officer. It was, therefore, with

some relief that in 1893 he accepted the none-too-attractive offer of a year’s contract

from an Indian firm in Natal, South Africa.

Years in South Africa

Africa was to present to Gandhi challenges and opportunities that he could hardly

have conceived. In the end he would spend more than two decades there, returning

to India only briefly in 1896–97. The youngest two of his four children were born

there.

Emergence as a political and social activist

Gandhi was quickly exposed to the racial discrimination practiced in South Africa. In

a Durban court he was asked by the European magistrate to take off his turban; he

refused and left the courtroom. A few days later, while traveling to Pretoria, he was

unceremoniously thrown out of a first-class railway compartment and left shivering

and brooding at the rail station in Pietermaritzburg. In the further course of that

journey, he was beaten up by the white driver of a stagecoach because he would not

travel on the footboard to make room for a European passenger, and finally he was

barred from hotels reserved “for Europeans only.” Those humiliations were the daily

lot of Indian traders and labourers in Natal, who had learned to pocket them with the

same resignation with which they pocketed their meagre earnings. What was new

was not Gandhi’s experience but his reaction. He had so far not been conspicuous for

self-assertion or aggressiveness. But something happened to him as he smarted

under the insults heaped upon him. In retrospect the journey from Durban to

Pretoria struck him as one of the most-creative experiences of his life; it was his

moment of truth. Henceforth he would not accept injustice as part of the natural or

unnatural order in South Africa; he would defend his dignity as an Indian and as a

man.

While in Pretoria, Gandhi studied the conditions in which his fellow South Asians in

South Africa lived and tried to educate them on their rights and duties, but he had no

intention of staying on in South Africa. Indeed, in June 1894, as his year’s contract

drew to a close, he was back in Durban, ready to sail for India. At a farewell party

given in his honour, he happened to glance through the Natal Mercury and learned

that the Natal Legislative Assembly was considering a bill to deprive Indians of

the right to vote. “This is the first nail in our coffin,” Gandhi told his hosts. They

professed their inability to oppose the bill, and indeed their ignorance of the politics

of the colony, and begged him to take up the fight on their behalf.

Until the age of 18, Gandhi had hardly ever read a newspaper. Neither as a student in

England nor as a budding barrister in India had he evinced much interest in politics.

Indeed, he was overcome by a terrifying stage fright whenever he stood up to read a

speech at a social gathering or to defend a client in court. Nevertheless, in July 1894,

when he was barely 25, he blossomed almost overnight into a proficient political

campaigner. He drafted petitions to the Natal legislature and the British government

and had them signed by hundreds of his compatriots. He could not prevent the

passage of the bill but succeeded in drawing the attention of the public and the press

in Natal, India, and England to the Natal Indians’ grievances. He was persuaded to

settle down in Durban to practice law and to organize the Indian community. In 1894

he founded the Natal Indian Congress, of which he himself became

the indefatigable secretary. Through that common political organization, he infused a

spirit of solidarity in the heterogeneous Indian community. He flooded the

government, the legislature, and the press with closely reasoned statements of Indian

grievances. Finally, he exposed to the view of the outside world the skeleton in the

imperial cupboard, the discrimination practiced against the Indian subjects of Queen

Victoria in one of her own colonies in Africa. It was a measure of his success as a

publicist that such important newspapers as The Times of London and The

Statesman and Englishman of Calcutta (now Kolkata) editorially commented on the

Natal Indians’ grievances.

In 1896 Gandhi went to India to fetch his wife, Kasturba (or Kasturbai), and their

two oldest children and to canvass support for the Indians overseas. He met

prominent leaders and persuaded them to address public meetings in

the country’s principal cities. Unfortunately for him, garbled versions of his activities

and utterances reached Natal and inflamed its European population. On landing at

Durban in January 1897, he was assaulted and nearly lynched by a white

mob. Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary in the British Cabinet, cabled the

government of Natal to bring the guilty men to book, but Gandhi refused to

prosecute his assailants. It was, he said, a principle with him not to seek redress of a

personal wrong in a court of law.

Resistance and results

Gandhi was not the man to nurse a grudge. On the outbreak of the South African

(Boer) War in 1899, he argued that the Indians, who claimed the full rights of

citizenship in the British crown colony of Natal, were in duty bound to defend it. He

raised an ambulance corps of 1,100 volunteers, out of whom 300 were free Indians

and the rest indentured labourers. It was a motley crowd: barristers and accountants,

artisans and labourers. It was Gandhi’s task to instill in them a spirit of service to

those whom they regarded as their oppressors. The editor of the Pretoria

News offered an insightful portrait of Gandhi in the battle zone:

After a night’s work which had shattered men with much bigger frames, I came across

Gandhi in the early morning sitting by the roadside eating a regulation army biscuit.

Every man in [General] Buller’s force was dull and depressed, and damnation was

heartily invoked on everything. But Gandhi was stoical in his bearing, cheerful and

confident in his conversation and had a kindly eye.

The British victory in the war brought little relief to the Indians in South Africa. The

new regime in South Africa was to blossom into a partnership, but only between

Boers and Britons. Gandhi saw that, with the exception of a few Christian

missionaries and youthful idealists, he had been unable to make a perceptible

impression upon the South African Europeans. In 1906 the Transvaal government

published a particularly humiliating ordinance for the registration of its Indian

population. The Indians held a mass protest meeting at Johannesburg in September

1906 and, under Gandhi’s leadership, took a pledge to defy the ordinance if it

became law in the teeth of their opposition and to suffer all the penalties resulting

from their defiance. Thus was born satyagraha (“devotion to truth”), a new technique

for redressing wrongs through inviting, rather than inflicting, suffering,

for resisting adversaries without rancour and fighting them without violence.

Mohandas Gandhi: Fact or Fiction?

The struggle in South Africa lasted for more than seven years. It had its ups and

downs, but under Gandhi’s leadership, the small Indian minority kept up its

resistance against heavy odds. Hundreds of Indians chose to sacrifice their livelihood

and liberty rather than submit to laws repugnant to their conscience and self-respect.

In the final phase of the movement in 1913, hundreds of Indians, including women,

went to jail, and thousands of Indian workers who had struck work in the mines

bravely faced imprisonment, flogging, and even shooting. It was a terrible ordeal for

the Indians, but it was also the worst possible advertisement for the South African

government, which, under pressure from the governments of Britain and India,

accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi on the one hand and the South African

statesman Gen. Jan Christian Smuts on the other.

“The saint has left our shores,” Smuts wrote to a friend on Gandhi’s departure from

South Africa for India, in July 1914, “I hope for ever.” A quarter century later, he

wrote that it had been his “fate to be the antagonist of a man for whom even then I

had the highest respect.” Once, during his not-infrequent stays in jail, Gandhi had

prepared a pair of sandals for Smuts, who recalled that there was no hatred and

personal ill-feeling between them, and when the fight was over “there was the

atmosphere in which a decent peace could be concluded.”

As later events were to show, Gandhi’s work did not provide an enduring solution for

the Indian problem in South Africa. What he did to South Africa was indeed less

important than what South Africa did to him. It had not treated him kindly, but, by

drawing him into the vortex of its racial problem, it had provided him with the ideal

setting in which his peculiar talents could unfold themselves.

The religious quest

Gandhi’s religious quest dated back to his childhood, the influence of his mother and

of his home life in Porbandar and Rajkot, but it received a great impetus after his

arrival in South Africa. His Quaker friends in Pretoria failed to convert him to

Christianity, but they quickened his appetite for religious studies. He was fascinated

by the writings of Leo Tolstoy on Christianity, read the Qurʾān in translation, and

delved into Hindu scriptures and philosophy. The study of comparative religion,

talks with scholars, and his own reading of theological works brought him to the

conclusion that all religions were true and yet every one of them was imperfect

because they were “interpreted with poor intellects, sometimes with poor hearts, and

more often misinterpreted.”

Shrimad Rajchandra, a brilliant young Jain philosopher who became Gandhi’s

spiritual mentor, convinced him of “the subtlety and profundity” of Hinduism, the

religion of his birth. And it was the Bhagavadgita, which Gandhi had first read

in London, that became his “spiritual dictionary” and exercised probably the greatest

single influence on his life. Two Sanskrit words in the Gita particularly fascinated

him. One was aparigraha (“nonpossession”), which implies that people have

to jettison the material goods that cramp the life of the spirit and to shake off the

bonds of money and property. The other was samabhava (“equability”), which

enjoins people to remain unruffled by pain or pleasure, victory or defeat, and to work

without hope of success or fear of failure.

Those were not merely counsels of perfection. In the civil case that had taken him to

South Africa in 1893, he had persuaded the antagonists to settle their differences out

of court. The true function of a lawyer seemed to him “to unite parties riven

asunder.” He soon regarded his clients not as purchasers of his services but as

friends; they consulted him not only on legal issues but on such matters as the best

way of weaning a baby or balancing the family budget. When an associate protested

that clients came even on Sundays, Gandhi replied: “A man in distress cannot have

Sunday rest.”

Gandhi’s legal earnings reached a peak figure of £5,000 a year, but he had little

interest in moneymaking, and his savings were often sunk in his public activities.

In Durban and later in Johannesburg, he kept an open table; his house was a virtual

hostel for younger colleagues and political coworkers. This was something of an

ordeal for his wife, without whose extraordinary patience, endurance, and selfeffacement Gandhi could hardly have devoted himself to public causes. As he broke

through the conventional bonds of family and property, their life tended to shade

into a community life.

Gandhi felt an irresistible attraction to a life of simplicity, manual labour, and

austerity. In 1904—after reading John Ruskin’s Unto This Last, a critique of

capitalism—he set up a farm at Phoenix near Durban where he and his friends could

live by the sweat of their brow. Six years later another colony grew up under Gandhi’s

fostering care near Johannesburg; it was named Tolstoy Farm for the Russian writer

and moralist, whom Gandhi admired and corresponded with. Those two settlements

were the precursors of the more-famous ashrams (religious retreats) in India, at

Sabarmati near Ahmedabad (Ahmadabad) and at Sevagram near Wardha.

South Africa had not only prompted Gandhi to evolve a novel technique for political

action but also transformed him into a leader of men by freeing him from bonds that

make cowards of most men. “Persons in power,” the British Classical scholar Gilbert

Murray prophetically wrote about Gandhi in the Hibbert Journal in 1918,

should be very careful how they deal with a man who cares nothing for sensual pleasure,

nothing for riches, nothing for comfort or praise, or promotion, but is simply determined to

do what he believes to be right. He is a dangerous and uncomfortable enemy, because his

body which you can always conquer gives you so little purchase upon his soul.

Return to India

Gandhi decided to leave South Africa in the summer of 1914, just before the outbreak

of World War I. He and his family first went to London, where they remained for

several months. Finally, they departed England in December, arriving in Bombay in

early January 1915.

Emergence as nationalist leader

For the next three years, Gandhi seemed to hover uncertainly on the periphery of

Indian politics, declining to join any political agitation, supporting the British war

effort, and even recruiting soldiers for the British Indian Army. At the same time, he

did not flinch from criticizing the British officials for any acts of high-handedness or

from taking up the grievances of the long-suffering peasantry in Bihar and Gujarat.

By February 1919, however, the British had insisted on pushing through—in the teeth

of fierce Indian opposition—the Rowlatt Acts, which empowered the authorities to

imprison without trial those suspected of sedition. A provoked Gandhi finally

revealed a sense of estrangement from the British raj and announced

a satyagraha struggle. The result was a virtual political earthquake that shook the

subcontinent in the spring of 1919. The violent outbreaks that followed—notably

the Massacre of Amritsar, which was the killing by British-led soldiers of nearly 400

Indians who were gathered in an open space in Amritsar in the Punjab region (now

in Punjab state), and the enactment of martial law—prompted him to stay his hand.

However, within a year he was again in a militant mood, having in the meantime

been irrevocably alienated by British insensitiveness to Indian feeling on the Punjab

tragedy and Muslim resentment on the peace terms offered

to Turkey following World War I.

By the autumn of 1920, Gandhi was the dominant figure on the political stage,

commanding an influence never before attained by any political leader in India or

perhaps in any other country. He refashioned the 35-year-old Indian National

Congress (Congress Party) into an effective political instrument of Indian

nationalism: from a three-day Christmas-week picnic of the upper middle class in

one of the principal cities of India, it became a mass organization with its roots in

small towns and villages. Gandhi’s message was simple: it was not British guns but

imperfections of Indians themselves that kept their country in bondage. His

program, the nonviolent noncooperation movement against the British government,

included boycotts not only of British manufactures but of institutions operated or

aided by the British in India: legislatures, courts, offices, schools. The campaign

electrified the country, broke the spell of fear of foreign rule, and led to the arrests of

thousands of satyagrahis, who defied laws and cheerfully lined up for prison. In

February 1922 the movement seemed to be on the crest of a rising wave, but, alarmed

by a violent outbreak in Chauri Chaura, a remote village in eastern India, Gandhi

decided to call off mass civil disobedience. That was a blow to many of his followers,

who feared that his self-imposed restraints and scruples would reduce the nationalist

struggle to pious futility. Gandhi himself was arrested on March 10, 1922, tried for

sedition, and sentenced to six years’ imprisonment. He was released in February

1924, after undergoing surgery for appendicitis. The political landscape had changed

in his absence. The Congress Party had split into two factions, one under Chitta

Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru (the father of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime

minister) favouring the entry of the party into legislatures and the other

under Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel opposing it.

Worst of all, the unity between Hindus and Muslims of the heyday of the

noncooperation movement of 1920–22 had dissolved. Gandhi tried to draw the

warring communities out of their suspicion and fanaticism by reasoning and

persuasion. Finally, after a serious outbreak of communal unrest, he undertook a

three-week fast in the autumn of 1924 to arouse the people into following the path of

nonviolence. In December 1924 he was named president of the Congress Party, and

he served for a year.

Return to party leadership

During the mid-1920s Gandhi took little interest in active politics and was

considered a spent force. In 1927, however, the British government appointed

a constitutional reform commission under Sir John Simon, a prominent English

lawyer and politician, that did not contain a single Indian. When the Congress and

other parties boycotted the commission, the political tempo rose. At the Congress

session (meeting) at Calcutta in December 1928, Gandhi put forth the crucial

resolution demanding dominion status from the British government within a year

under threat of a nationwide nonviolent campaign for complete independence.

Henceforth, Gandhi was back as the leading voice of the Congress Party. In March

1930 he launched the Salt March, a satyagraha against the British-imposed tax on

salt, which affected the poorest section of the community. One of the most

spectacular and successful campaigns in Gandhi’s nonviolent war against the British

raj, it resulted in the imprisonment of more than 60,000 people. A year later, after

talks with the viceroy, Lord Irwin (later Lord Halifax), Gandhi accepted a truce

(the Gandhi-Irwin Pact), called off civil disobedience, and agreed to attend

the Round Table Conference in London as the sole representative of the Indian

National Congress.

The conference, which concentrated on the problem of the Indian minorities rather

than on the transfer of power from the British, was a great disappointment to the

Indian nationalists. Moreover, when Gandhi returned to India in December 1931, he

found his party facing an all-out offensive from Lord Irwin’s successor as viceroy,

Lord Willingdon, who unleashed the sternest repression in the history of the

nationalist movement. Gandhi was once more imprisoned, and the government tried

to insulate him from the outside world and to destroy his influence. That was not an

easy task. Gandhi soon regained the initiative. In September 1932, while still a

prisoner, he embarked on a fast to protest against the British government’s decision

to segregate the so-called “untouchables” (the lowest level of the Indian caste system;

now called Scheduled Castes [official] or Dalits) by allotting them separate

electorates in the new constitution. The fast produced an emotional upheaval in the

country, and an alternative electoral arrangement was jointly and speedily devised by

the leaders of the Hindu community and the Dalits and endorsed by the British

government. The fast became the starting point of a vigorous campaign for the

removal of the disenfranchisement of the Dalits, whom Gandhi referred to as

Harijans, or “children of God.”

In 1934 Gandhi resigned not only as the leader but also as a member of the Congress

Party. He had come to believe that its leading members had adopted nonviolence as a

political expedient and not as the fundamental creed it was for him. In place of

political activity he then concentrated on his “constructive programme” of building

the nation “from the bottom up”—educating rural India, which accounted for 85

percent of the population; continuing his fight against untouchability; promoting

hand spinning, weaving, and other cottage industries to supplement the earnings of

the underemployed peasantry; and evolving a system of education best suited to the

needs of the people. Gandhi himself went to live at Sevagram, a village in central

India, which became the centre of his program of social and economic uplift.

The last phase

With the outbreak of World War II, the nationalist struggle in India entered its last

crucial phase. Gandhi hated fascism and all it stood for, but he also hated war. The

Indian National Congress, on the other hand, was not committed to pacifism and was

prepared to support the British war effort if Indian self-government was assured.

Once more Gandhi became politically active. The failure of the mission of Sir Stafford

Cripps, a British cabinet minister who went to India in March 1942 with an offer that

Gandhi found unacceptable, the British equivocation on the transfer of power to

Indian hands, and the encouragement given by high British officials

to conservative and communal forces promoting discord between Muslims and

Hindus impelled Gandhi to demand in the summer of 1942 an immediate British

withdrawal from India—what became known as the Quit India Movement.

Mohandas K. Gandhi

Mohandas K. Gandhi, 1931.

James A. Mills/AP/Shutterstock

In mid-1942 the war against the Axis powers, particularly Japan, was in a critical

phase, and the British reacted sharply to the campaign. They imprisoned the entire

Congress leadership and set out to crush the party once and for all. There were

violent outbreaks that were sternly suppressed, and the gulf between Britain and

India became wider than ever before. Gandhi, his wife, and several other top party

leaders (including Nehru) were confined in the Aga Khan Palace (now the Gandhi

National Memorial) in Poona (now Pune). Kasturba died there in early 1944, shortly

before Gandhi and the others were released.

Aga Khan Palace (Gandhi National Memorial)

Aga Khan Palace (Gandhi National Memorial), Pune, India.

© Hemera/Thinkstock

A new chapter in Indo-British relations opened with the victory of the Labour

Party in Britain 1945. During the next two years, there were prolonged triangular

negotiations between leaders of the Congress, the Muslim League under Mohammed

Ali Jinnah, and the British government, culminating in the Mountbatten Plan of

June 3, 1947, and the formation of the two new dominions of India and Pakistan in

mid-August 1947.

Witness the funeral procession for Mahatma Gandhi, February 2, 1948

Funeral procession for Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi, February 2, 1948, with a quote from the

eulogy by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Public DomainSee all videos for this article

It was one of the greatest disappointments of Gandhi’s life that Indian freedom was

realized without Indian unity. Muslim separatism had received a great boost while

Gandhi and his colleagues were in jail, and in 1946–47, as the final constitutional

arrangements were being negotiated, the outbreak of communal riots between

Hindus and Muslims unhappily created a climate in which Gandhi’s appeals to

reason and justice, tolerance and trust had little chance. When partition of the

subcontinent was accepted—against his advice—he threw himself heart and soul into

the task of healing the scars of the communal conflict, toured the riot-torn areas

in Bengal and Bihar, admonished the bigots, consoled the victims, and tried to

rehabilitate the refugees. In the atmosphere of that period, surcharged with suspicion

and hatred, that was a difficult and heartbreaking task. Gandhi was blamed by

partisans of both the communities. When persuasion failed, he went on a fast. He

won at least two spectacular triumphs: in September 1947 his fasting stopped the

rioting in Calcutta, and in January 1948 he shamed the city of Delhi into a communal

truce. A few days later, on January 30, while he was on his way to his evening prayer

meeting in Delhi, he was shot down by Nathuram Godse, a young Hindu fanatic.

Place in history of Mahatma Gandhi

The British attitude toward Gandhi was one of mingled admiration, amusement,

bewilderment, suspicion, and resentment. Except for a tiny minority of Christian

missionaries and radical socialists, the British tended to see him at best as a utopian

visionary and at worst as a cunning hypocrite whose professions of friendship for the

British race were a mask for subversion of the British raj. Gandhi was conscious of

the existence of that wall of prejudice, and it was part of the strategy of satyagraha to

penetrate it.

Pune, Maharasthra, India: Gandhi Memorial Stone

Gandhi Memorial Stone, Gandhi National Memorial, Pune, Maharasthra, India.

© Hemera/Thinkstock

His three major campaigns in 1920–22, 1930–34, and 1940–42 were well designed

to engender that process of self-doubt and questioning that was to undermine

the moral defenses of his adversaries and to contribute, together with the objective

realities of the postwar world, to producing the grant of dominion status in 1947. The

British abdication in India was the first step in the liquidation of the British

Empire on the continents of Asia and Africa. Gandhi’s image as a rebel and enemy

died hard, but, as it had done to the memory of George Washington, Britain, in 1969,

the centenary year of Gandhi’s birth, erected a statue to his memory.

Gandhi had critics in his own country and indeed in his own party. The liberal

leaders protested that he was going too fast; the young radicals complained that he

was not going fast enough; left-wing politicians alleged that he was not serious about

evicting the British or liquidating such vested Indian interests as princes and

landlords; the leaders of the Dalits doubted his good faith as a social reformer; and

Muslim leaders accused him of partiality to his own community.

Research in the second half of the 20th century established Gandhi’s role as a great

mediator and reconciler. His talents in that direction were applied to conflicts

between the older moderate politicians and the young radicals, the political terrorists

and the parliamentarians, the urban intelligentsia and the rural masses, the

traditionalists and the modernists, the caste Hindus and the Dalits, the Hindus and

the Muslims, and the Indians and the British.

It was inevitable that Gandhi’s role as a political leader should loom larger in the

public imagination, but the mainspring of his life lay in religion, not in politics. And

religion for him did not mean formalism, dogma, ritual, or sectarianism. “What I

have been striving and pining to achieve these thirty years,” he wrote in his

autobiography, “is to see God face to face.” His deepest strivings were spiritual, but

unlike many of his fellow Indians with such aspirations, he did not retire to a cave in

the Himalayas to meditate on the Absolute; he carried his cave, as he once said,

within him. For him truth was not something to be discovered in the privacy of one’s

personal life; it had to be upheld in the challenging contexts of social and political

life.

Gandhi won the affection and loyalty of gifted men and women, old and young, with

vastly dissimilar talents and temperaments; of Europeans of every religious

persuasion; and of Indians of almost every political line. Few of his political

colleagues went all the way with him and accepted nonviolence as a creed; fewer still

shared his food fads, his interest in mudpacks and nature cure, or his prescription

of brahmacarya, complete renunciation of the pleasures of the flesh.

Gandhi’s ideas on sex may now sound quaint and unscientific. His marriage at the

age of 13 seems to have complicated his attitude toward sex and charged it with

feelings of guilt, but it is important to remember that total sublimation, according to

one tradition of Hindu thought, is indispensable for those who seek self-realization,

and brahmacarya was for Gandhi part of a larger discipline in food, sleep, thought,

prayer, and daily activity designed to equip himself for service of the causes to which

he was totally committed. What he failed to see was that his own unique experience

was no guide for the common man.

Scholars have continued to judge Gandhi’s place in history. He was the catalyst if not

the initiator of three of the major revolutions of the 20th century: the movements

against colonialism, racism, and violence. He wrote copiously; the collected edition

of his writings had reached 100 volumes by the early 21st century.

Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi: postage stamp

Image of Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi depicted on a postage stamp from Cyprus.

© iStock/Thinkstock

Much of what he wrote was in response to the needs of his coworkers

and disciples and the exigencies of the political situation, but on fundamentals he

maintained a remarkable consistency, as is evident from the Hind Swaraj (“Indian

Home Rule”), published in South Africa in 1909. The strictures on Western

materialism and colonialism, the reservations about industrialism and urbanization,

the distrust of the modern state, and the total rejection of violence that was

expressed in that book seemed romantic, if not reactionary, to the pre-World War I

generation in India and the West, which had not known the shocks of two global wars

or experienced the phenomenon of Adolf Hitler and the trauma of the atom bomb.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s objective of promoting a just and egalitarian

order at home and nonalignment with military blocs abroad doubtless owed much to

Gandhi, but neither he nor his colleagues in the Indian nationalist movement wholly

accepted the Gandhian models in politics and economics.

In the years since Gandhi’s death, his name has been invoked by the organizers of

numerous demonstrations and movements. However, with a few outstanding

exceptions—such as those of his disciple the land reformer Vinoba Bhave in India

and of the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., in the United States—those

movements have been a travesty of the ideas of Gandhi.

Yet Gandhi will probably never lack champions. Erik H. Erikson, a distinguished

American psychoanalyst, in his study of Gandhi senses “an affinity between Gandhi’s

truth and the insights of modern psychology.” One of the greatest admirers of Gandhi

was Albert Einstein, who saw in Gandhi’s nonviolence a possible antidote to the

massive violence unleashed by the fission of the atom. And Gunnar Myrdal, the

Swedish economist, after his survey of the socioeconomic problems of the

underdeveloped world, pronounced Gandhi “in practically all fields

an enlightened liberal.” In a time of deepening crisis in the underdeveloped world, of

social malaise in the affluent societies, of the shadow of unbridled technology and the

precarious peace of nuclear terror, it seems likely that Gandhi’s ideas and techniques

will become increasingly relevant.

Leadership Qualities

Mahatma Gandhi was a very empowering and Visionary leader. Mahatma Gandhi was an empowering

leader no only because he empowered all Indians on a salt march to corrupt the British economic

system. Since he was pioneer of Satyagraha, he also inspired all Indians to understand and

learn resistance through non-violent civil disobedience. Gandhi was a visionary leader. He

gave Indians a new spirit, a sense of self-respect and a feeling of pride in their civilization, he is

something more than a mere politician. He is a great statesman and a man of vision.

In India, Gandhi established the acknowledgment by leading through example, he established himself

as a slave of the people of India, empowering the general public. He made it his policy to practice what

he preached, even the small things like spinning yarn to make his clothes. He resorted to simple and

poor living, just like millions in the country, hence people looked at Gandhi as one of their own, they

could see their own sufferings in him.

Gandhi had already been recognized through his work and movements in South Africa. People

already had great honor and hopes from him due to what he had achieved, his non-violent methods

were also very well respected within the Indian society. Since he was already visionary and

empowering, Mahatma Gandhi was a Transformational leader. He always empowered his followers

towards success, he gave them hope where there may be none. One of the most outstanding

qualities of Gandhi which makes him a great transformational leader of modern history was his long

term vision, self confidence which was perhaps perceived as someone who was stubborn and strong

principles of righteousness

Had he come of age today, Gandhi might have branded himself as a “social entrepreneur”. In reality,

few social entrepreneurs have achieved anywhere near the scale of impact that Gandhi was able

to. But the comparison is apt, as Gandhi was never a head of state or government, but instead, the

head of a private organization - the Indian National Congress, that, along with its many partners,

mobilized an incredibly diverse and complex peoples into a united movement against British

imperialism. He led first and foremost by understanding the diversity of India and its people –

economically, culturally, religiously, and deeply integrating that diversity into the Independence

movement. He further integrated himself into the movement by dedicating his life to the cause,

living as much among the people as possible, and actually risking death many times for the

cause. While there may never be another Gandhi, there is no reason that today’s committed social

entrepreneurs can’t embrace their own version of Gandhi’s personal and political leadership

commitment.

Arguably, Gandhi’s greatest leadership trait was his ability to visualize the qualities of a successful,

post-Independence Indian nation, and maintain a life-long focus on the four intertwined challenges

that he believed must be collectively addressed for India to achieve success as a nation. The four

challenges, or goals, as articulated by Ramchandra Guha in his book, “Gandhi, The Years That

Changed The World”; were: to free India from British occupation, to end untouchability, to improve

relations between Hindus and Muslims, and to make India into a self-reliant nation – economically

and socially. Gandhi aligned most of the social movements he led around these four goals - starting

with his work in South Africa and continuing until his death. He believed firmly that without

addressing all four challenges simultaneously, India could not acquire independence and become a

successful nation. Without communal harmony between Hindus and Muslims, or between upper

caste and lower caste Hindu’s, for example, Gandhi did not believe India would ever achieve its

potential.

A second element of Gandhi’s leadership was his lifelong commitment to achieving that intertwined

vision of a successful Indian nation. Starting in the 1890’s with his work in South Africa until his

death in 1948, Gandhi wrote, mobilized and preached about the same goals of freedom, inclusion,

harmony, diversity and empowerment. Today, few of the most committed social entrepreneurs

have the energy to stay engaged on the same set of issues for 50-60 years. Dr. Muhammad Yunus of

the Grameen Bank has been one, very notable exception.

Gandhi’s most well-known, and most-studied, leadership trait was his willingness to live like the

majority of Indians that he sought to help, and his exhortation that all Indians “be the change they

wish to see in this world”. It seems obvious, but in a day and age when NGO leaders are in Davos,

London and New York as much as they are in the villages, and when NGO salaries remain a hot topic,

Gandhi’s ability to live comfortably among villagers and the urban poor – to be the change he wished

to see, brought him the credibility, trust and intellectual understanding needed to lead India’s

independence movement. While today’s social entrepreneurs also have compelling visions for

change, they are often unable to separate themselves from the global elite to which they have

historically belonged. And fairly or unfairly, many for-profit entrepreneurs and social enterprises are

perceived as seeking to profit off the backs of the world’s poor, and never gain credibility, even

when their primary objective and motivation is to improve the human condition.

Gandhi’s least studied leadership trait was his ability to use the fast as a social and political

weapon. Over the course of his life time, Gandhi fasted 14 times for social, religious or political

purposes – a skill he mastered through personal practice. He would fast for personal penance and to

build his own capacity for sacrifice, ahimsa and brahmacharya.

Today in business and entrepreneurship, we often talk about core competency and disruptive

innovation. Entrepreneurs are told to develop a product or service that is difficult to compete

against - technically complex, different from the past and very difficult to replicate by others.

Gandhi’s ability to fast for social change was his core competency. It took him many years to train

his body and mind to function without food, and only later did he use the fast as a political

weapon. No one else could do it and there was no answer for it – from anyone. The British never

had an effective response, nor did angry Indian communal rioters. In each case, Gandhi’s fasts

brought capitulation to his wishes, because anything was a more acceptable solution than to allow

Gandhi’s death. It was a great innovation in social movements that, except for Cesar Chavez’s fasts

for farm workers in California, has never been remotely replicated.

The elements of Gandhi’s leadership model remain relevant today. Whether a leader is seeking to

end sexual discrimination, eradicate HIV/AIDS or legislate a jobs program, they will need their own

version of Gandhi’s leadership model - re-imagined in their own vision. In the age of the #MeToo

movement, for example, leaders for gender equality and an end to sexual harassment must attack

the intertwined issues of religion, family structure, sexism, and the transformation of labor

markets. Similarly, to eradicate the HIV virus will require new drugs and vaccines, but will also

transformation in the health care system, cultural norms around sexuality, building rural health

delivery programs and many other things. These will take a life time to achieve and require leaders

with great credibility and trust amongst the communities they are seeking to help and

change. Gandhi was able to maintain the support of India’s upper caste Hindu’s and industrialists

while maintaining the trust of the rural and poor.

What’s missing today is the 2019 version of the fast. We have major global crises in areas like

climate change and forced migration, but no leaders who have yet found tools, like Gandhi’s fast-tilldeath, to push public opinion and government leaders to action. Our greatest commemoration of

Gandhi’s life may be to find the tools that lead to large-scale change non-violently, but forcibly in the

same manner that he did so effectively.

Champions of Human Rights

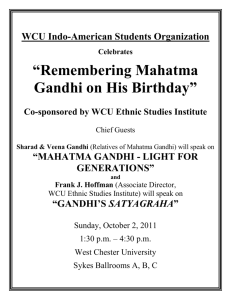

MAHATMA GANDHI (1869–1948)

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi is widely recognized as one of the twentieth

century’s greatest political and spiritual leaders. Honoured in India as the father

of the nation, he pioneered and practiced the principle of Satyagraha—resistance

to tyranny through mass nonviolent civil disobedience.

While leading nationwide campaigns to ease poverty, expand women’s rights,

build religious and ethnic harmony and eliminate the injustices of the caste

system, Gandhi supremely applied the principles of nonviolent civil disobedience,

playing a key role in freeing India from foreign domination. He was often

imprisoned for his actions, sometimes for years, but he accomplished his aim in

1947, when India gained its independence from Britain.

Due to his stature, he is now referred to as Mahatma, meaning “great soul.”

World civil rights leaders—from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Nelson Mandela—have

credited Gandhi as a source of inspiration in their struggles to achieve equal

rights for their people.

Bapu's leadership qualities and skills

Gandhi would teach us countless lessons about life, leadership and much more.

Gandhi learnt his Leadership skills during his years in South Africa, and honed them

in India.

He was naturally charismatic. He had a "feel" for his Follower's needs which was

uncannily correct. But he did develop formal tools and methods to become a better

Leader over time. He had a rock-solid value system from which all of his activities

stemmed, he wanted to make major changes at every turn in his life, and he had a

totally interdependent relationship with his followers. As a man of action, he

used the 4 E's throughout his life: Envision, Enable, Empower, and

Energize. Although there are many traits and behaviors that caused the success of

Gandhi, the research has a few picked ingredients:

1. Leadership by examples

Gandhi's greatest ability was to walk his talk at every level and in every way. India

continues to be a nation of many diverse nationalities but never did they so

unanimously identify with another leader as they identified with Gandhi and this was

across classes and communities which were even more sharply divided than they are

these days. He practiced what he preached at every possible level. Be it how he

dressed like the poorest Indian with a hand woven cotton cloth that barely covered his

body and had the simplest of watches and glasses. When it came to personal

possessions, unlike today's leaders he had the barest of minimum.

2. Treatment to others

His letters and writings to other great leaders in India, the world and even to young

children never had a patronizing or "holier-than-thou" element but always looked at

everyone as equals. Leaders who have put their interests over the organizations they

created have prospered as individuals but always at the cost of the institution they built

or worked for. He made an effort to truly understand his people. He spoke from their

point of view...from what motivated them. It has been said that, when he spoke publicly

to large audiences it was like he was speaking to you individually.

3. Persistence

A critical success for Gandhi was the support he got across the nation and in the

international community. A significant part of this was due to his extraordinary

persistence once he had articulated his vision and his methods. His determination in

following through on what he preached was often at cost to his own well-being.

4. Constant Growth

Gandhi would understand the importance of continual growth in his life. Despite being

an accomplished leader in his community, he continually sought out greater

understanding through much study of religious scripture. As a leader, one must also

understand the need for constant growth.

5. Strength Is Not Shown Through Muscle Power

Gandhi displayed great strength, not through using his strength to force others to bend

to his will, but by using nonviolent means to achieve his goals. As a leader, it is a very

simple matter to leverage on your position or your authority to coerce people to bend

to your will. However, it is your true strength as a leader that can persuade and

convince people to follow you with their hearts. Learn to use respect to win people

over, instead of using power to bend people to your will. The force of power never wins

against the power of love. Right Against Might...Mahatma.

6. An Eye For An Eye Will Only Make The Whole World Blind

History can attest to the fact that most human conflicts have been as a result of a

stubborn approach by our leaders. Our history would turn out for the better if our

leaders could just learn that most disputes can be resolved by showing a willingness

to understand the issues of our opponents and by using diplomacy and compassion.

No matter where we live, what religion we practice or what culture we cultivate, at the

heart of everything, we are all humans. We all have the same ambitions and

aspirations to raise our family and to live life to its fullest. Our cultural, religious and

political differences should not provide the backbone to invoke conflicts that can only

bring sorrow and destruction to our world.

7. Become The Change, We Want To See

A great leader always leads with an exemplary life that echoes his ideals. Mahatma

Gandhi sacrificed his thriving law practice and adopted a simple life to live among the

millions who lived in poverty during his freedom struggle. Today, we see modern

leaders cajoling the masses with promises that they never intend to keep - let alone

practicing what they preach in their own lives. One cannot bring world peace to all

unless a leader demonstrates peaceful acts of kindness daily.

8. Reasonable

Even after stating that India would be divided over his dead body, he realised that

partition was inevitable as the only solution to the Hindu-Muslim divide, and accepted

it. Although Gandhi was a man of faith, he did not create any specific dogma for his

followers. Gandhi believed in the unity of all mankind under one God, and preached

Hindu, Muslim and Christian ethics.

9. Strategist

Ideas travel very fast. Gandhi is a fascinating figure. He was a wonderful strategist,

showman and leader. He had an amazing public relations network and a very good

relationship with the press then. For instance, the Dandi march, if Gandhi had gone

there quietly, it would just not have made an impact. He knew he had to create an

event to make an impact and so he took his followers on a march that stirred popular

imagination of the time. He had a total understanding of the human psychology and

used it along with his public relation skills.

10. Discipline

Mahatma believed that challenging his self discipline heightened his commitment to

achieving his goals. He was a focused leader that had a "Do or Die" attitude. He 'would

free India or die in the process. Mahatma would do extraordinary things to improve his

discipline and his commitment.

IMPLICATION OF HIS TRAITS IN MANAGEMENT TODAY

Management is best an expertise. Do what others cannot so you gain authority over

them. So, to be a good leader you need to be very skillful to construct bridges of

empathy with people. Else one will never be in their shoes and they will not follow...

because you don't know them and they can feel it. This is also why most people find it

easier to be managers. Management can be taught. Leadership must be cultivated.

Mahatma Gandhi was a leader who kept working on himself till he became the man

worthy of gaining a country's following. He took a stand on issues. He said, "A 'No'

uttered from the deepest conviction is better than a 'Yes' merely uttered to please, or

worse, to avoid trouble." A manager would try to please in order to diffuse a situation.

A leader will not worry about creating a situation.

1. Reinvent

Gandhi reinvented the rules of the game to deal with a situation where all the available

existing methods had failed. He broke tradition. He understood that you cannot fight

the British with force. Resource constraint did not bother him. Have the courage to

invent the means. Change the paradigm on how we can run.

2. Clarity of Goals and Definite Purpose

He aimed at a common agenda. That was the motivation. He suggests that India needs

to fundamentally change the way it can grow. He unleashed the power of ordinary

people in the country to fight under a unifying goal. If one can understand the motive

of your opponent's leadership; one can find ways to tackle it.

3. Adopt Styles To Suit The Culture (Flexibility)

We keep feeling that models of people in the West are the ones we should follow. In

a way, we remain subservient to the leadership values and models of the West. But

since the last two to three years these models are being doubted even in the West,

and so it is time for India to look within itself for leadership examples. The country

today stands divided on whether what he did was good or bad. There was neither a

leader before him nor one after him who could unite us all and bring us out in the

streets to demand for what rightfully ours. Gandhi advocated having leadership styles

that were dependent on the circumstances. When Gandhi was in South Africa, he

launched his protests in a suit and a tie. But when he came back to India, he thought

of khadi and launched non-violent protests on a greater scale. At times Gandhi had to

be quite flexible leader. At times he had to change his plans around to counter British

rules and tactics.

4. People's Empowerment

According to him, Gandhi's style of leadership as applied to corporate India would

involve making even the lowest person in the organization believe in it and the

significance of his contribution towards it. In business, empowerment is all about

making sure everyone is connected to the organization's goals. Gandhi has a way of

doing that: making sure that everyone in the cause is connected to the goal. Gandhi's

example as a manager and leader is extraordinary. There was no one like him who

could get people together to embrace his vision as their vision. His belief was probably

the most important factor in Mahatma's success. He not only had self belief but he had

the ability to inspire the Indian people to believe in themselves and their goal of

freedom, even through all the hardships that they faced. One of Mahatma's beliefs

was Willpower Overcomes Brut Force.

5. Social Progress

Leadership is a necessary part of the social process. Any group, association,

organization or community functions the way its leader leads it. It is truer in the

collectivistic cultures like India where people follow the path shown by the great

people. Leadership is an integral part of work and social life. In fact in any given

situation where a group of people want to accomplish a common goal, a leader may

be required. Leadership behaviour occurs in almost all formal and informal social

situations. Even in a non formal situation such as a group of friends some sort of

leadership behaviour occurs wherein one individual usually takes a lead in most of the

group activities.

6. Transcend Adversaries

The first time Mahatma got up to speak in court, when he was working as a lawyer, he

could not speak one word out loud due to fear. This caused him great humiliation.

Even though he failed miserably, those failures eventually lead to him becoming one

of the best public speakers of all time. There were quite a number of times Gandhi

failed; each time he used the failure to improve his leadership skills and to improve

himself and the task at hand. Mahatma shows us that the even the best leaders still

fail and make mistakes. He also shows that the difference between good leaders and

great leaders is that the great leaders acknowledge and learn from their mistakes.

7. Inspire and Motivate

Leader must have ability to move the masses; it's not just true for political leaders, but

also organizational leaders. Simply lead with your heart and show that you actually

believe in the purpose of what you stand for. Emotions are contagious, both that of

optimism & pessimism and must be guarded in public. Even in crucial and uncertain

times, it's important to keep positive emotions. While it is important to communicate

reality, it's equally necessary to give sense of hope. Leaders must encourage a culture

of pride in the employees; they should be able to harness the collective creative

energies of an organization. A leader must have the ability to bring out the best in

others, to enable others to act. When the employees feel that they "only work here",

the leadership has typically failed.

8. Credibility

Credibility is single most important quality of a good leader; it is the foundation. A

foundation that is build with honesty, integrity, and self-discipline. Employees look up

the leaders as the role models, or simply the person who brings meaning to their daily

job. If the leaders can't practice the solid values they preach, their ideas will be

shrugged off. Every leader must realize that employees are constantly observing and

analyzing their actions, evaluating consistency between their work and their deeds,

judging their integrity. Leaders must exercise self-discipline by suppressing their own

personal egos or emotions.

9. Long lasting relationships

In today's era on communication, relationships are not only important but crucial.

Opinion of every person counts. A leaders job is not only limited to planning, creating

strategies and organizational structure, but to make sure that they are establishing the

kind of personal relationships that employees wish to seek. Employees must find their

leaders accessible, they like to hear from them first hand rather than through their

managers. The open door policy should not be used as a mere buzz word.

Truly, management is completely different from leadership. Like opposite ends of a

coin. While Gandhi might have been 'managing' the Indian freedom movement with a

troop of comrades on clockwork precision, he was actually leading a change of

mindset that effected change in everyone who participated with him.

CONCLUSIONS AND FINDINGS

Gandhi’s entire life story is about action, to bring about positive change. He both

succeeded and failed in what he sought to do, but he always moved forward and he

never gave up the quest for improvement, both social and spiritual, and both for

individuals and for the Nation as a whole. Today, Gandhi is remembered not only as

a political leader, but as a moralist who appealed to the universal conscience of

mankind. He changed the world.

Gandhi’s effect on the world was and still is immense. He also gave to the world a way

of thinking about and acting upon value systems that profoundly influenced such

important figures as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. From a practical viewpoint, his

focus on "Swadeshi" formed the core of India’s industrial policy. Gandhi’s success and

continued reputation make him a leader worthy to learn from. All of us who aspire to

lead ethically may never “be like him”.

Gandhi’s relevance, is more so today as many more are educated, articulate and

ambitious. In such times, leaders can lead only if they not only have their content right

but are also better people with a vision for themselves and others. While Gandhi might

have been ‘managing’ the Indian freedom movement with a troop of comrades, he was

actually leading a change of mindset that effected change in everyone who

participated with him.

One of his most admirable qualities was that he led by example and never preached

what he himself was not willing to do.

He was charismatic, but he was also deliberate and analytical. He was a

transformational and transactional leader too.

Mahatma Gandhi taught us that we can bring harmony to our world by becoming

champions of love and peace for all.

If all of us do our bit, to be like him in every relationship we forge at work and

elsewhere, we have no doubt that our successors will inherit a better world.

SUGGESTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

You can manage people but that will only be because you have the authority to do so

bestowed upon you. But you can lead from anywhere, so that your influence infects

others and regardless of your position or authority, they follow what you say. The

leadership skills that he showed stemmed from his focus on a definite purpose,

discipline and his belief systems. Business gurus in India are talking about a new role

model: Mahatma Gandhi. The Father of the Nation is now being held up as the master

strategist, an exemplary leader, and someone whose ideas and tactics corporate India

can emulate.

Gandhi's ideas are of particular relevance to India at this juncture to become an

economic superpower. So the leadership styles in management that we see with

Gandhi famous quotes are distinctively what anyone can evolve into being.

Mahatma Gandhi's Leadership - Moral And Spiritual

Foundations

Mahatma Gandhi is universally accepted as an exemplary model of ethical and moral

life, with a rare blending of personal and public life, the principles and practices, the

immediate and the eternal. He considered life to be an integrated whole, growing from

'truth to truth' every day in moral and spiritual status.

He believed in a single standard of conduct founded on dharma of truth and

nonviolence. He successfully led nonviolent struggles against racial discrimination,

colonial rule, economic and social exploitation and moral degradation. So long as

these manifestations of violence remain, Gandhi will remain relevant. Gandhi was "a

good man in a world where few resist the corroding influence of power, wealth and

vanity".1

Among the vital messages of Gandhi's leadership are: even one person can make a

difference; strength comes not from physical capacity but from an indomitable will;

given a just cause, nonviolence and capacity for self-suffering, and fearlessness,

victory is certain; leadership by example is the one most effective. He asserted: "We

only wish to serve our fellowmen wherever we may be..." (CWMG 54:233)

Considering Gandhi's unique and multi-faceted leadership, an attempt has been made

to study his leadership under three main headings:

Ethico-social Parameters of Gandhian Leadership;

Gandhian Leadership - The Vision and the Way; and

Gandhian Political-Economic-Social Order.

I

Ethico-Social Parameters

Gandhi spoke in a low tone and was a hesitant public speaker. Yet people of all

classes were drawn to him and instinctively felt him to be a leader of deeply spiritual

and moral perceptions, which he sought to realize through the pursuit of Truth. Over

54 years of Gandhi's public life were lived as an open book. He lived in South Africa

for 21 years and then in India from 1915. All through his life he remained a seeker

after Truth.

A central quality of his leadership was its natural evolution through intense interaction

with the people and the events. He was acutely conscious of his own imperfections.

"One great reason for the misunderstanding lies in my being considered almost a

perfect man...I am painfully conscious of my imperfections, and therein lies all the

strength I posses, because it is a rare thing for a man to know his own limitations"

(CWMG 21:457-9). The more he realized about human fallibility, the more he tried to

evolve morally and spiritually. When nothing else availed, he would seek refuge in God

and yet carry on.

Gandhi single-handedly made nonviolence a universal substitute for violence and the

bed-rock of his leadership. His nonviolence was the way to counter injustice and

exploitation, and not run away from a righteous battle. He associated the qualities of

humility, compassion, forgiveness and tolerance as corollaries of nonviolence.

Humility, to him, is "an indispensable test of ahimsa. In one who has ahimsa in him it

becomes part of his very nature," and, it must not be "confounded with mere manners

or etiquette," but it "should make the possessor realize that he is as nothing" (CWMG

44:205-6).

To Gandhi the spirit of service and sacrifice was the key to leadership. For the spirit of

service to materialize we must lay stress on our responsibilities and duties and not on

rights. He illustrated it through the example of "concentric circles": one starts with

service of those nearest to one and expands the circle of service until it covers the

universe, no circle thriving at the cost of the circles beyond. Service to him implied

self-sacrifice. He said: "Sacrifice is the law of life. It runs through and governs every

walk of life. We can do nothing or get nothing without paying a price for it...in other

words, without sacrifice" (CWMG 4:112).

The commitment to service, however demands a strong sense of conscience (moral

imperative), courage (fearlessness, bravery, initiative), and character (integrity). To

Mahatma Gandhi, 'inner voice' was synonymous with conscience. Leaders need to

develop and follow their conscience even more than ordinary people as they set the

path for others. Hence, he wrote: "None of us, especially no leader should allow

himself to disobey the inner voice in the face of pressure from outside. Any leader who

succumbs in this way forfeits his right of leadership (CWMG 34:363-4). For a leader

to follow the right path requires courage and its associated qualities: "Courage,

endurance and above all, fearlessness and spirit of willing sacrifices are the qualities

that are required today in India for leadership" (CWMG 21:152).

Gandhi in his time wielded more power over the minds of people than any other

individual but it was not the power of weapons, or terror, or violence; it was the power

of his convictions, his pursuit of truth and nonviolence, fearlessness, love and justice,

working through incessant service and sacrifice for fellow human beings. His power

came from empowering the weak, to lead the masses in the fight against injustice,

exploitation, violence and discrimination. Satyagraha elevated the struggle for survival

to the highest moral-spiritual levels and ordinary, emaciated people turned heroes. His

power arose through the people whom he gave a sense of self-respect, purpose and

moral strength.

We may thus conclude that Gandhi's leadership was a running ethical lesson to his

followers as well as his opponents on 'how to live'. An outline of the basic ethical tenets

of Gandhian leadership, proceeding from the eternal verities towards the more applied

principles of conduct are given below:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Truth

Nonviolence

Right Means and Right Ends

Primacy of Duties over Right

The Deed, not the Doer

True Religion (Universality and Brotherhood)

Aparigraha or Non-possession (voluntary Poverty)

Yajna (Sacrifice and Service)

Satyagraha or Nonviolent Conflict Resolution

II

The Vision And The Way

Gandhi's Vision

Mahatma Gandhi was not an armchair academician or a cloistered visionary. He was

deeply concerned with the world around him. He disclaimed being a visionary. He said:

"Mere discipline cannot make leadership. The latter calls for faith and vision" (CWMG

72:217). The core of his vision for the people of India was contained in his concept of

Swaraj, the fountainhead from which the whole range of the concepts of Gandhian

philosophy flow. It necessarily starts with political self-rule as a means to achieving

economic, social and moral freedom. It applies equally to the individual, the society

and the state.

His concept of freedom was self-rule, i.e. self-restraint and not freedom from all

restraint which "independence often means" (CWMG 45:264). "Swaraj means

freedom not only for oneself but "for your neighbour too" (CWMG 60:254), because,

"Men aspiring to be free could hardly think of enslaving others. If they try to do so, they

would only be binding their own chains of slavery tighter" (CWMG 87:162). He defined

Swaraj as a social state "in which the poorest shall feel it is their country in whose

making they have an effective voice....no high class and low class of people....all

communities shall live in perfect harmony....no room in such an India for the curse of

untouchablility or....of intoxicating drinks and drugs. Women will enjoy the same rights

as men" (CWMG 47:389).

Inherent in his vision of Swaraj was his vision of democracy: "Democracy, disciplined

and enlightened, is the fines thing in the world" (CWMG 47:236).

Gandhi's Way: Satyagraha

The philosophy of Satyagraha has been explained in simple terms by Gandhi himself,

as appearing in the 'Congress Report on the Punjab Disorders, chap. IV: Satyagraha'

(see CWMG 17:151-58):

"The principles of satyagraha, as known today, constitute a gradual evolution. Its root

meaning is 'holding on to truth'; hence truth-force. I have also called it love-force or

soul force. In the application of satyagraha, I discovered in the earliest stages that

pursuit of truth did not admit of violence being inflicted on one's opponent, but that he

must be weaned from error by patience and sympathy. For what appears to be truth

to one, may appear to be an error to the other. And patience means selfsuffering....Satyagraha....has been conceived as a weapon of the strongest, and

excludes the use of violence in any shape or form ...I feel that nations cannot be one

in reality, nor can their activities be conducive to the common good of the whole

community, unless there is this definite recognition and acceptance of the law of the

family in national and international affairs...Satyagraha has therefore been described

as a coin, on whose face you read love and on the reverse you read truth...A

satyagrahi does not know what defeat is..."

"And as a satyagrahi never injures his opponent and always appeals, either to his

reason....or his heart....satyagraha is twice blessed; it blesses him who practices it,

and him against whom it is practiced. Satyagraha....is essentially a....process of

purification and penance. It seeks to secure reforms or redress of grievances by selfsuffering."

In the Gandhian philosophy of satyagraha, dialogue and compromise―except on

basic principles―play a vital part. He writes in his Autobiography: "All my life through,

the very insistence on truth has taught me to appreciate the beauty of compromise. I

saw in later life that this spirit was an essential part of satyagraha" (CWMG 39:122).

III

Gandhian Political-Economic-Social Order

Spiritualizing Politics

Mahatma Gandhi never sought a public or political office or title. He was in politics for