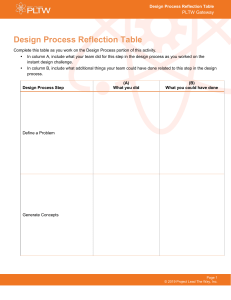

SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, EDUCATION AND SOCIAL WORK COVER SHEET FOR COURSEWORK Please upload your assignment using the assignment link in Canvas MODULE CODE SWK2013 MODULE TITLE Practice Learning Level 2 UGR MODULE CONVENOR Danielle Mackle STUDENT NUMBER 40128702 WORD COUNT 3799 Please tick to indicate that your practice teacher has seen this assignment If you have an INDIVIDUAL STUDENT SUPPORT MEMO to be considered in assessment of your written work, please confirm the reasonable adjustments that have been recommended for you ☒ ☐ ☐ ☐ *NB: You must discuss and AGREE any flexibility with deadlines with the Module Convenor If you have applied for EXCEPTIONAL CIRCUMSTANCES to be permitted additional time to submit without penalty, please confirm this by checking the box opposite ☐ ACADEMIC INTEGRITY Please note that plagiarism (which among other things includes downloading from the Web and copying from the work of other students), will be severely penalized. I confirm that: I have read the University regulations on plagiarism, and that the attached submission is my own original work. No part of it has been submitted for any other assignment, and I have acknowledged in my notes and bibliography all written and electronic sources used. I am submitting a copy of the work to Canvas and agree that the School may scan the work with plagiarism detection software. YES Flexibility with deadlines for assignments* Consideration for spelling Consideration for grammar Throughout this assignment, I will critically analyse and reflect upon my first Practice Learning Opportunity (PLO). I will provide an overview of key aspects of my learning and demonstrate my personal and professional development since its commencement using Gibb’s Model of reflection (1988), as illustrated through my work with two service users with whom I shall refer to as young person ‘X’ and young person ‘Y’. I will outline how the application of knowledge, skills and values enhanced my practice, giving particular emphasis to antioppressive practise (AOP). I will conclude by identifying key areas for future professional development, considering how best to address them. Reflection Firstly, reflective practice is a core tenet within social work and can be best understood as the process through which individuals learn through and from past experiences, reflecting on it in the present to gain new insight into one's ‘self’ (Boud et al, 1985; Ruch 2000). It is a powerful tool that aids social workers in bridging the gap between theory and practice (Thompson, 1996) while challenging ‘biased or distorted thinking (Houston, 2015, p.8). Thus, reflective practice helps to highlight an individual’s learning needs for the guidance of future practice (Quinn, 1988). Moreover, key role six of the Northern Ireland Framework Specification for the Degree in Social Work (DHSSPS, 2015) indicates that to become a professionally competent practitioner, social workers must take personal responsibility to engage in what Finlay (2008) refers to as a process of ‘life-long learning’ in the pursuit of self-awareness through continuously critically analysing and evaluating practice (p.1). As Houston (2015) outlines, this consequently leads to improvements within the quality of practice and contributes to better outcomes for service users. However, knowing how to begin to engage in reflective practise often proves to be a challenging task for many social work students. According to Boyd and Fales (1983), to develop the critical skill of reflection one must first be aware of how to be an effective learner. Therefore, at the beginning of my PLO, my practice teacher encouraged me to ‘tune in’ to how I learn by completing a series of questionnaires to figure out my personal learning style. Upon completion of the Honey and Mumford questionnaire, I scored as a ‘reflector’ someone who learns best through observing and thinking things through before acting (Honey and Mumford, 1992). This insight into my learning style proved to be significant in aiding the development of my professional reflection as it helped me to facilitate a better understanding of what informs my actions. This questionnaire was completed again at the end of my PLO to highlight progress throughout my learning journey. Notably, the results indicated that I had developed as both an activist and theorist due to the unique learning experiences I had during my PLO, allowing me to link theories to practice and take a more proactive approach in situations (Frantz, J. et al,2017). Furthermore, given that I am a social work student and that the concept of ‘reflective practice’ is relatively new to me; throughout my PLO I kept a reflective journal. Alongside supervision – where I received direction, feedback, and constructive criticism – my reflective journal acted as a ‘vehicle for reflection’ (Moon, 2006, p.1). This informed my learning and supported me to become more critical and perceptive of my learning experiences, thus aiding my personal and professional development (McConnell, 2006 as cited in Knott and Scragg 2007; Tate, 2013; Dewey, 1993). Through the guidance and support of my practice teacher, I was encouraged to not only engage in practical reflection but also emancipatory reflection (Sicora, 2017). This assisted me in making sense of my experiences in a meaningful manner, enabling me to capture and connect my thoughts, feelings, and actions. While at the same time, helping me to consider situations outside of oneself by analyzing the power relations and oppressive forces that may have created a barrier to effective practice (Taylor, 2010). The significance of this reflection throughout my supervision sessions and journal entries proved to be crucial as a key theme throughout my PLO and this paper centres around ‘power’ within the client-worker relationship (Tew, 2006) and anti-oppressive practice (Thompson 2012). Reflective model: In terms of reflective frameworks, while I will refer to alternative reflective theories such as that of Schön (1983) to explore the different ways in which I reflect (e.g., reflecting ‘on’ and ‘in’ action), I have chosen to utilize Gibb’s (1988) model of reflection (Figure 1) throughout this assignment. Due to also being a visual learner – as identified through Vark’s learning style questionnaire- I found that the ‘reflective cycle’ diagram (Figure 1) works best for my learning style as it enables me to visually conceptualize the idea of reflection into six stages, providing a straightforward yet comprehensive framework for working through and examining experiences (Fleming and Millis, 1992). Figure 1: Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle. Setting: My PLO was based in a residential care home for adolescents. It is an eight-bedded residential home that provides medium to long-term care for young people between the ages of 12-18 years old. Throughout my PLO the ages of the current young people living in the home ranged between 13-17. Each young person has experienced a myriad of challenges (e.g., drug/alcohol misuse, behavioural and mental health issues) that stemmed largely from deeply embedded trauma during their childhood (Strijbosch et al, 2015 as cited in Children’s Social Care, 2021). While older social work literature still refers to residential homes as ‘units’ or ‘facilities,’ many of the young people I worked alongside during my PLO expressed how strongly they disliked such terms as they feel there is a stigma associated with such language and suggests that they are living in an institution similar to a prison facility, for example (PDDW, 15, 9, 21). According to Steels and Simpson (2017) using such language is damaging as “it gives a negative message to society that only the ‘worst’ children live in residential care” (p.1404). Applying Thompson’s (2012) PCS model, it is clear that this is oppressive on a wider cultural level and reinforces the negative stereotype that children and young people living in residential homes are ‘troublesome’ (Emond, 2003). Therefore, considering this, you will notice that I have adopted the term ‘home’ instead as I -alongside the young people I worked alongside during my PLObelieve that it aligns more with AOP. Role and responsibility: My role within the team could be characterized by what Maier (1981 as cited in Milligan 2006) refers to as the ‘core of care which is marked by the rhythms and rituals of the home’ (p.11), with its ‘requirements to work in the moment yet to connect the immediate to the overall experience of the young people (Smith, 2003, p.242). My duties involved working directly with the young people, both on an individual and group basis, continuously assessing the risk and needs of each young person daily, implementing care plans and providing ongoing personal, emotional, and social support as well as working alongside other members of staff and multidisciplinary agencies (Ward, 2007). The Children (Northern Ireland) Order (1995) alongside The Human Rights Act (1998) and The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) are the three fundamental pieces of legislation through which Residential Child Care services are underpinned. The procedures outlined in these pieces of legislation guided all the care planning, safeguarding, and therapeutic assessments I completed as well as the direct work I undertook alongside the young people. Reflection on practice Young person ‘X’ The first of the two cases I will reflect upon will be my work with young person ‘X’ during a critical incident. I will focus on the ethical dilemma that arose regarding the necessity of balancing the rights and wishes of the service users alongside balancing the complexity of risk within the ‘care versus control’ debate (Banks, 2012). Young person ‘X’ is a seventeen-year-old female who has been living in her current residential home for the past three years. Young Person ‘X’ is the subject of a full Care Order under Article 50 of the Children’s (NI) Order 1995. She has a confirmed history of neglect and emotional and physical abuse by her birth parents. There are also allegations of sexual abuse by young person ‘X’s father. Young person ‘X’ has no current contact with either of her birth parents. She ‘X’ has a history of drugs and alcohol misuse and has expressed suicidal ideation in the past. As young person ‘X’ is now legally at the age where she can cease to be looked after by the Trust, she has decided that she would like to move out of the residential home and into independent living. This will take place within the coming months. In preparation for this, young person ‘X’ currently resides in the semi-independent flat that is attached to the residential home in preparation for her transition into independent living. Young person ‘X’ has also recently entered vocational education and has begun working a part-time job. Due to the major changes that are currently occurring in young person ‘X’s life, it was important that I had an insight into the impact of transition within an individual's life course from adolescence into the early stage of adulthood (Walker and Crawford, 2014). Upon reflection, tuning in to this helped me to better understand the impact of ’stress as well as the opportunity for positive change created by transition’ (Hutchison, 2019, p.353). Reading ‘Helping Children in Care Cope with Change’ (Jay,2015) made me aware that young person ‘X’ is likely to experience a sense of loss and grief as she prepares for her new beginnings and adjusts to the prospect of life outside of residential care (Kubler-Ross, 2005). Loss and grief can present itself in many different forms and generate an array of complex responses which can seep into an individual’s behavior (Sweetman and O’Donnell, 2020). Therefore, it was important that I built a strong professional relationship with young person ‘X’ in order to effectively support her during this time (Trevithick, 2012). On the particular occasion in question, I answered a call from young person ‘X’ who informed me that she had taken between eight-ten paracetamol tablets over a short space of time while at work and was feeling unwell. I can recall initially feeling deeply concerned for young person ‘X’s wellbeing, fearing that she may overdose due to her consumption. Urdang (2010) disputes that if social workers do not ‘master their own feelings, then the ground is ripe for problems to occur’ (p.526). Therefore, I reflected in action (Schön, 1983) and quickly recognized that I needed to remain calm and contain my own emotions and anxieties surrounding the situation to ensure they did not manifest themselves into my response and intervention (Sheldon, 1995). Failure to do so may have led to countertransference and further distressed young person ‘X’ who was already unsettled and upset (Breda and Feller, 2014). Throughout the duration of the call, I actively listened and employed an empathetic and sensitive tone to help communicate and reassure young person ‘X’ that I was there to support her (Cournoyer, 2013; McLeod 2007). This acted as a form of ‘support intervention’ during an emotionally charged time (Kadushin and Kadushin, 1997, p.205) and helped to calm young person ‘X’ and alleviate her concerns that staff would be angry with her. Moving on, I then asked young person ‘X’ to elaborate on the situation (e.g., why did you take that many tablets?). At that time, I thought that using predominantly open-ended questions would enable young person ‘X’ to formulate her thoughts and feelings into her own words, assisting me in gathering a more extensive understanding and aid the risk assessment and management of the situation (Trevithick, 2012; Campbell and Taylor, 2020). However, my approach proved ineffective as young person ‘X’ replied with “I don’t know” and “why are you asking me that.” While it was not my intention, the wording of my initial questions may have appeared critical and judgmental, and this may have resulted in young person ‘X’ not wanting to engage with me due to her feeling as though my questions were ‘accusatory or authoritarian’ (Campbell and Taylor, 2020; Seden 2005, p.29). Recognizing ambivalence and realizing that time was of the essence, I adapted my questioning technique to stimulate greater participation by using Hargie’s (2004) inverted funnel questioning style. By using closed questions to begin with (e.g., are you currently suicidal), enabled me to elicit the necessary factual information, while following up with a probing question helped me to gain a more in-depth understanding of the case at hand (e.g., how were you feeling before taking the tablets?) (Trevithick, 2012). Reflecting upon the value of ‘individualization,’ a key learning point that I gained from this experience is that one style does not fit all when it comes to working alongside service users (Biestek, 1961). Therefore, for future practice, I must ensure that I adapt and adjust my interviewing/assessment style accordingly to support the individual needs and requirements of each service user and their situation. Moreover, after seeking medical advice, it was recommended that young person ‘X’ attend the hospital. I advised young person ‘X’ that she should inform her manager that she was unwell and needed to go home as a safety precaution to which she refused. I was disheartened by young person ‘X’s unwillingness to cooperate given the severity of the situation. My immediate response was that, if young person ‘X’ did not inform them herself that I would call into her work and inform her boss. My rationale behind taking such a directive approach was that the safety of young person ‘X’ was paramount, and I had to base my decision on what I perceived to be within her best interest based on the available information I had at that time (Trevithick, 2012; Campbell and Taylor, 2020). However, ‘reflecting on action’ (Schön, 1983), it is apparent that I disempowered and oppressed young person ‘X’ by negatively exercising my structural power and authority as a social work student, providing her with an ultimatum which left her with no other choice other than to comply (Thompson, 2012; Walker and Beckett, 2011). As a result of this, I sought the advice and guidance of my practice teacher during supervision of how to deal with such situations to improve future practice. While we both acknowledged that I had a duty of care to safeguard young person ‘X,’ my practice teacher encouraged me to consider a service users’ right to autonomy and self-determination in making their own choices and decisions – even in times of crisis, given they have the capacity to do so (PDDW, 11/11/21). Upon reflection, applying a person-centred approach (Rodgers, 1943) would have assisted me to better understand young person ‘X’s hesitation while enabling me to communicate risks more effectively (Campbell and Taylor, 2020). This in turn may have helped to facilitate a greater partnership and assisted young person ‘X’ and I to come to a joint decision collaboratively based on respect, honesty, and mutual understanding as opposed to me forcing a decision upon her (Koprowska, 2014; Egan, 2014). Young person ‘Y’ The second case that I will focus on involves Young Person ‘Y’ - a fourteen-year-old female who is currently being voluntarily accommodated under Article 21 of the Children (NI) Order (1995). Young person ‘Y’s childhood has been characterized by what Bellis et al (2016) would refer to as multiple adverse childhood experiences (i.e., growing up in a household in which her father had a substance misuse problem and mental ill health) and trauma (i.e., sexually assault). These experiences have greatly impacted young person ‘Y’ and she now exhibits challenging and harmful behaviour which is believed to be linked to her exposure to these chronic stress situations (Hughes, 2012). Young person ‘Y’ has a history of absconding quite regularly and often demonstrates violence and aggression towards staff and those she views as figures of ‘authority’ (e.g., social services, police, and medical personnel etc.). The main theme of my learning while working alongside young person ‘Y’ centred around how to effectively deal with conflict and challenging behaviours in a way that does not negatively impact the professional working relationship between the service users and I. My first encounter with young person ‘Y’ took place at the beginning of my PLO under challenging circumstances as she had absconded from the home and her emotions were extremely heightened. While shadowing a fellow Residential Social Worker (RSW), young person ‘Y’ demonstrated extreme verbal aggression towards me and threatened to physically harm me. This initially shocked me because of the language and hostility displayed and as a result, I found it difficult to keep my composure and responded by ‘freezing’ (Levenson, 2017). The RSW had to intervene and de-escalate the situation which left me feeling incompetent and I began to question my abilities and whether I possessed the confidence and professional skills to overcome challenging and resistant behaviour (Trevithick, 2012). During supervision I expressed my frustrations, outlining how I was disappointed in myself due to my inability to ‘reflect in action’ (Schön, 1983) and think on my feet using the knowledge, skills, and values I had developed during my Preparation for Practice Module the previous year. My practice teacher indicated that, although I felt panicked during the interaction, I had in fact acted accordingly given the timing and circumstances (PDDW, 22,08,21) Considering I had not yet established any form of relationship with young person ‘Y,’ attempting to prematurely challenge the situation could have had a detrimental impact on our future working relationship (Trevithick, 2012). Furthermore, Gibbs (1986) emphasizes the significance of making sense of why situations occur in order to effectively learn from past experiences. In retrospect, although I reviewed young person ‘Y’s case notes and spoke with members of staff who made me aware that young person ‘Y’ struggles to come to terms with her traumatic childhood and the stigma of being a ‘Looked after child,’ I had failed to consider and anticipate how my presence as an unfamiliar social work student in her home may have unsettled young person ‘Y’ (Wilkinson et al, 2017). In this situation, Trevithick (2012) emphasizes the importance of drawing upon our theoretical and empirical knowledge base in order to “understand how experiences are perceived, understood and communicated” by individual service users and how this impacts behaviour (p.2). Hawkins-Rodgers (2007) highlights the centrality of consistency, stability and familiarity for young people living in residential homes as a means of supporting them through their trauma. While Levenson (2017) states that it is not unusual for ‘looked after children’ to be wary of individuals and situations they are unfamiliar with due to their inner working model (Bowlby, 1988) processing their “expectations of the world as an unsafe place in which relationships are fraught with danger and disappointment” (p.109). Reflecting upon this during supervision with my practice teacher helped me to understand that young person ‘Y’s hostility towards me was probably not personal but rather a defence mechanism due to me ‘disrupting’ the status quo within the home which incited her ‘fight or flight response because of her adverse childhood experiences (Herman, 1992). As a result of this, I was prompted to broaden my understanding of trauma-informed care as a model of intervention when working alongside young person ‘Y’ (Levenson, 2017). This enabled me to view young person ‘Y’s case more holistically and assisted me in empathetically engaging with her (Carr, 2003; Dill, 2016). Thus, young person ‘Y’ and I were able to build a strong therapeutic alliance based on “kindness and respect and listening and reacting with curiosity and compassion” (Levenson, 2017, p.110). I established that simple everyday actions such as helping her with homework or engaging in conversations about things she was interested in helped us to build a strong rapport and facilitated a supportive environment in which young person ‘Y’ felt comfortable expressing her feelings and concerns in an open and honest manner with me (Lefevre, 2010). In comparison to the beginning and end of my work with young person ‘Y’ I feel that much had been achieved. Although young person ‘Y’ continued to test boundaries and exhibit challenging behaviour throughout the entirety of my PLO, I was able to gain a newfound understanding of what might ‘trigger’ young person ‘Y’ into a ‘conflict cycle' (TCI Handbook, 2013). This understanding, alongside the positive working relationship that we had established greatly assisted me in deescalating and resolving conflict situations with her in a way that was restorative and preserved our relationship (Campbell and Taylor, 2020). By undertaking further training (e.g., Sanctuary and Therapeutic Crisis Intervention Training) and knowledge of the ‘Just Right State’ Materials; (Bhreathnach, 2019) which facilitates the process of self-regulation and co-regulation through the use of food, sensory activities and enriched environment provision and observing how other members of staff effectively dealt with similar situations, I was able to reflect upon what I learned and incorporate it into my own practice. For example, when working with young person ‘Y’ during times of crisis, I learned of the importance of an enriched environment and effective verbal communication. Using short and simple sentences that were jargon-free and paraphrasing back to her demonstrated that I had listened to what she was saying and helped me to support young person ‘Y’ to recover back to her baseline behaviour (Trevithick, 2012; TCI Handbook, 2013). Future learning: Reflecting on my practice throughout my first PLO ‘X’ using Gibbs ‘Reflective Cycle’ has offered ‘conclusions and constructs to guide future decisions and actions’ (Svinicki and Dixon, 1987.p141). Each experience, interaction, and relationship I built with the individual young people during my time on PLO offered a unique learning opportunity for personal and professional growth and development. This has assisted me in gaining greater self-awareness and enabled me to identify both my strengths and weaknesses which I will strive to improve upon as I progress into level three. For example, for my future learning needs, I have identified that I need to learn to enhance my delivery of anti-oppressive practice by gaining a greater understanding and appreciation of my role as a student social worker and the power relations that come along with it (Smith, 2013). This will help me to avoid unconsciously oppressing other service users in the future as I had with young person ‘X’ during our telephone call. Moreover, while I acknowledged I have made considerable progress in my ability to manage challenging crisis situations during my time on PLO, I still have much to learn as I am only at the beginning of my social work journey therefore, I need to engage in a continuous commitment to reflect upon my practice in order to ensure I provide the highest standard and quality of care to those I am serving to ensure that their needs are fully met. References Banks, S (2012) Ethics and Values in Social Work. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Bellis, M, Ashton, K Hughes, K, Ford, K, Bishop, J and Paranjothy, S. (2016). Adverse Childhood Experiences and their impact on health-harming behaviors in the Welsh adult population. Public Health, Wales. Available at: www.researchgate.net/publication/290433553_Adverse_Childhood_Experienc es_and_their_impact_on_health- harming_behaviours_in_the_Welsh_adult_population. (Accessed 12th December 2021). Bhreathnach, E (2019) ‘Just Right States’, Sensory Processing, Coordination and Attachment, The Repair of Early Trauma: A "Bottom Up " Approach'. Beacon Family Services. Boud, D., Keogh, R. and Walker, D. (1985) Promoting reflection in learning: a model. In D. Boud, R.Keogh and D. Walker (eds.) Reflection: turning experience into learning. London: Kogan Page. Bowlby, J (1988) A secure base; parent-child attachment and healthy human development, London: Routledge. Breda. A.V and Feller, T (2014) Social Work Students’ Experience and Management of Countertransference’. Social Work Journal Vol 50, No 4. University of Johannesburg. Available at: http://socialwork.journals.ac.za/pub http://dx.doi.org/10.15270/50-4386 (Accessed 09th December 2021) Carr, A (2003). Family Therapy: concepts, processes and practice. Dublin: Wiley. Children's Social Care. (2021) Residential care - What Works for Children's Social Care. [online] Available at: <https://whatworkscsc.org.uk/evidence/evidence-store/intervention/residential-care/> [Accessed 25 November 2021]. Cournoyer, B (2013) The Social Work Skills Workbook: Cengage Learning Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety & Northern Ireland Social Care Council, (2015)., ‘Northern Ireland Framework for Specification for the Degree in Social Work’, Northern Ireland Social Care Council. Available at: www.niopa.qub.ac.uk/bitstream/NIOPA/1409/1/Norther%20Ireland%20Framewor k%20Specification%20for%20the%20Degree%20in%20Social%20Work.pdf (Access ed: 06th December 2021). Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books. (Original work published 1910). Egan, G., 2018. The Skilled Helper: A Problem-Management and Opportunity- Development Approach to Helping. 12th ed. Mason, OH: Cengage. Emond, R (2003) Putting the Care into Residential Care: The Role of Young People. Journal of Social Work. Volume 67, Issue 6. Fleming ,N .D. and Mills, C.(1992), ‘Not Another Inventory, rather a Catalyst for Reflection, To improve the Academy’ Vol.11,1992. New Zealand: Lincoln University. Frantz, J. et al. (2017). An exploration of learning styles used by social work students: a systematic review. Southern African Journal of Social Work and Social Development, 29(1): 92–106. Goldstein, B., and B. Bokoros. 1992. “Tilting at Windmills: Comparing the Learning Style Inventory and the Learning Style Questionnaire.” Educational and Psychological Measurement Hargie, O et al (2004) Skilled Interpersonal Communication. Research, Theory and Practice. 4th edn. Hove. Routledge. Hawkins-Rodgers, Y (2007) Adolescents adjusting to a group home environment: A residential care model of re-organizing attachment behavior and building resiliency, Children and Youth Services Review, Volume 29, Issue 9. Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—From domestic abuse to political terror. New York, NY: Basic Books. Hensenfeld, Y (1987) Power in social work practice, Social Service Review Vol. 61, No. 3 , The University of Chicago Press. Houston, S (2015). Reflective Practice: A model for Supervision and Practice in Social Work. Belfast, NISCC. Honey, P and Mumford, A (1992) The manual of learning styles questionnaire. Maidenhead: Peter Honey Publications. Hughes, D (2012) Parenting Matters. Emotional and Behavioura; Difficulties. Coram BAAF Adoption and Fostering Academy. London. Hutchison, E. D. (2019) ‘An Update on the Relevance of the Life Course Perspective for Social Work’, Families in Society, 100(4). Jay, C (2015), ‘Helping Children in Care Cope with Change’, Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care April 2015 – Vol.14, No.1. Kadushin, A and Kadushin, G (1997) The Social Work Interview: A Guide for Human Service Professionals, 4th edn, New York: Columbia University Press. Koprowska, J., 2014. Communication and Interpersonal Skills in Social Work. 4th ed. Exeter: Learning Matters. Lefevre, M (2010) Communicating with Children and Young People: Making a difference. Bristol. Policy Press. Levenson, J (2017) Trauma-Informed Social Work Practice, Social Work, Volume 62, Issue 2. McLeod, J (2007) Counselling Skills. Maidenhead. Open University Press. Milligan, I, (2006) Residential childcare: collaborative practice. London; Thousand Oaks, Calif. :Sage Publications Moon, J. (2006) Learning Journals: A handbook for reflective practice and professional development (2nd edn) Abingdon: Routledge. Northern Ireland Social Care Council (2019) Standards of Codes and Practice in Social Work, Available at: https://niscc.info/storage/resources/new_proof_00000_niscc_social_work_stud ents_border.pdf. (Accessed 26th November 2021). Personal and Professional Development Workbook (PPDW) 2021. Ruch, G. (2000) “Self and Social Work: towards an integrated model of learning”. Journal of Social Work Practice. Vol.14, No.2. Sedenn, J (2005) Counselling Skills in Social Work Practice. 2nd edn. Maidenhead. Open University Press. Sicora, A (2017) Reflective Practice and Learning from Mistakes in Social Work. Policy Press. University of Bristol. Sheldon, B (1995) Cognative-behavioural Therapy: Research, Practice and Philosophy. London: Routledge. Smith, M (2003) Towards a professional identity and Knowledge base: is residential childcare still social work? Journal of Social Work. Steels,S and Simpson, H (2017) Perceptions of Children in Residential Care Homes: A Critical Review of the Literature. The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 47, Issue 6. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/articleabstract/47/6/1704/4554337. (Accessed: 12th December 2021). Svinicki, M and Dixon, N. (1987). The Kolb Model Modified for Classroom Activities. College Teaching. Issue 35. Sweetman, A and O’Donnell,S (2020) ‘Non-Death Loss and Grief’. Irish Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. Vol 20 , No.3. Tate, S (2013) ‘Writing to Learn: writing reflectively? in C. Bulman and S. Schutz (ed) reflective practice in health care (5th edn), London: Backwell. Taylor, B.J. (2010) Reflective Practice for HealthCare Professionals (3rd edn), Berkshire: McGraw-Hill. Tew, J (2006) ‘Understanding Power and Powerlessness: Towards a framework for Emancipatory practice in Social Work’ Journal of Social Work. Vol 6 (1): 33-51. The Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1995. London: Stationery Office. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/nisi/1995/755/contents/made. (Accessed 20th November 2021 The Human Rights Act (1998). London: Stationery Office. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/42/contents. (Accessed 07th December 2021). The (United Nations) Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989. [Online] Available from: http://www.unicef.org.uk/Documents/Publicationpdfs/UNCRC_PRESS200910web.pdf [Accessed on: 20 November 2021] Therapeutic Crisis Intervention Handbook (2013). Southeastern Trust Learning Resources. Thompson, N (1996) People skills: a guide to effective practice in human services. Basingstoke: Macmillan. Thompson, N (2012) Ani-discriminatory Practice. London. Palgrave Macmillan. Thompson, N., (2015). Understanding Social Work; Preparing for Practice. 4th ed. Macmillan Education UK. Trevithick, P. (2003) “Effective Relationship-based Practice: A Theoretical Exploration”. Walker, J and Crawfor, K (2014). Social Work and Human Development. 4th edn. Sage Publications, Learning Matters Ltd. Walker, S. and Beckett, C., 2011. Social Work Assessment and Intervention. Lyme Regis: Russell House Pub. Ward, A (2007), Working in Group Care: Social Work and Social Care in Residential and Day Care Settings (2nd edn). Bristol, BASW/Policy Press. Wilkinson, J and Bowyer S (2017). The impacts of abuse and neglect on children; and comparison of different placement options. Evidence review. Research in Practice. Department of Education. Available at:www.assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/att achment_data/file/602148/Childhood_neglect_and_abuse_comparing_placement _options.pdf (Accessed 14th December 2021).