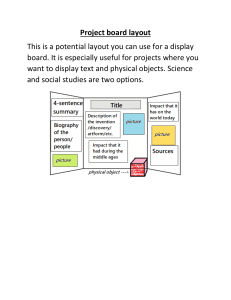

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238048111 Wayfinding in Libraries: Can Problems Be Predicted? Article in Journal of Map & Geography Libraries · January 2012 DOI: 10.1080/15420353.2011.622456 CITATIONS READS 39 2,090 2 authors: Rui Li Alexander Klippel University at Albany, The State University of New York Wageningen University & Research 34 PUBLICATIONS 482 CITATIONS 193 PUBLICATIONS 2,773 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: ENAbLE - Educational Advancement of ICT-based spatial Literacy in Europe View project Immersive Learning Research Network (ILRN) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Alexander Klippel on 06 October 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Journal of Map And Geography Libraries, 8:21–38, 2012 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1542-0353 print / 1542-0361 online DOI: 10.1080/15420353.2011.622456 Wayfinding in Libraries: Can Problems Be Predicted? RUI LI and ALEXANDER KLIPPEL Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA The main library at the authors’ university campus, with its large size and multiple-level structures, is challenging for patrons to navigate. Requests for directions are among the most frequently posed questions at help desks in this library. As a first step toward improving wayfinding aids, such as maps or signs, we took a spatial science perspective of combining spatial and behavioral approaches to reveal objectively areas where wayfinding problems occur. To this end, we employed formal spatial descriptions of the environment addressing visibility, layout complexity, and connectivity. The term coined in the literature for these methods is “space syntax.” Additionally, we used a behavioral approach to investigate actual wayfinding behaviors of library patrons and compared these behaviors with the results of the space syntax analysis. The results show that a building’s layout complexity and visual access potentially predicts how well patrons find their goals (books and other materials). Other aspects such as signs or individual characteristics of patrons were also found to play a role in understanding human wayfinding performance. The goal of this study was to broadly explore wayfinding problems in relation to the environment and to individual characteristics of patrons, such as their familiarity and sense of direction. Our approach introduces an objective perspective to assess wayfinding problems in libraries. Thereby, it provides potentially valuable information for library administrators towards the improvement of the design of library wayfinding systems. Research for this paper is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0948601. The views, opinions, and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of the National Science Foundation or the U.S. Government. Address correspondence to Rui Li, Department of Geography, GeoVISTA Center, 302 Walker, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802. E-mail: rui.li@psu.edu 21 22 R. Li and A. Klippel KEYWORDS tems wayfinding, space syntax, library, wayfinding sys- INTRODUCTION Anecdotally referred to as a maze, the interior spaces of the main library on the authors’ university campus (hereafter, “the library”) bring a challenge for patrons to navigate. The library’s three wings (Paterno, Central Stacks, and West Pattee) are connected only on the first floor and all have different physical structures and layouts. This layout complexity increases the possibility of patrons’ having trouble finding their way, and these troubles persist despite considerable efforts on the part of library administration to install new signage. We identified two important research questions: (1) whether the current wayfinding systems are informative and cognitively adequate according to the requirement of effectively solving wayfinding problems (Strube, 1992); and (2) where library patrons have wayfinding problems and whether these places can be identified through a quantitative assessment of environmental characteristics. Both research questions attempt to reveal wayfinding problems in the library. The first research question addresses individual strategies for acquiring knowledge from wayfinding systems and using this knowledge to navigate effectively. For example, maps are commonly used to provide general location information about the major areas of the library. However, designing maps specifically for wayfinding support is not trivial, and, for example, orienting a map such that it is misaligned with the map readers’ frame of reference (for example, “up” in the map should correspond to “in front of”) increases their cognitive load in interpreting the map (Levine, 1982; Warren and Scott, 1993; Shepard and Hurwitz, 1984). A comprehensive overview of design considerations for these location specific you-are-here (YAH) maps, extending the original work by Levine (1982), can be found in Klippel, Freksa, and Winter (2006). Factors going into YAH map design can be attributed to the relation between environment and map or to map characteristics as such. In case of the latter, for example, the amount of information shown on a YAH map influences how quickly and how accurately that information can be read (Meilinger et al., 2007). Similarly, using signs requires careful planning, as misplaced signs can increase the chances of getting lost (Carr, 2006). The second and more central focus of this paper is analyzing the influences of both the physical environment and patrons’ individual characteristics on wayfinding performance in libraries. By physical environment, we mean (for example) the building layout, book stacks structure, and the book cataloguing/organizing scheme, all of which can play a large part in determining how difficult it is for patrons to find their way. Likewise, individual characteristics include how familiar a patron is with the library and how Wayfinding in Libraries 23 good the patron’s general sense of direction (spatial awareness) is. In sum, as an essential step to improve wayfinding systems and reduce wayfinding problems, this study attempts to identify those aspects of both physical environment and individual spatial awareness that cause wayfinding problems in the library. We first introduce theories that elucidate environmental factors related to indoor wayfinding problems, and then we give brief descriptions of the tools we chose to formally analyze the environment. We present a behavioral study that we designed to shed light on the intricate relationship between environmental and individual characteristics and wayfinding performance. We present the results of both formal analyses and behavioral experiments. Finally, because the wayfinding problems we identified may be common to multiple indoor environments, we provide suggestions for improving the wayfinding systems, both those tailored to the library in this study, and to public buildings in general. Assessing Environmental Characteristics Human wayfinding behaviors are influenced by different factors of the physical environment. The three most important factors were identified by Lynch (1960) to reflect the ease of understanding and finding one’s way in an environment: differentiation of the environment, visual access, and complexity of the spatial layout. Lynch also introduced the term legibility to describe how characteristics of different environments contribute differently to the development of cognitive maps and to subsequent wayfinding behaviors. In the following paragraphs, we introduce each factor and then summarize their relation to wayfinding problems. First, the degree of differentiation can help wayfinders recognize locations. Evans and collaborators (1984) suggested that varying sizes, forms, colors, or architectural styles can help wayfinders distinguish locations. If a location is easily distinguished from others, the likelihood of getting lost would be lower. In a library environment, for example, signs and color codes are used to specify locations of collections. As many libraries expand over time through the addition of wings or new buildings, they may also have architecturally distinguishing characteristics. These features can be used by patrons to identify their current location. Second, visual access, also referred to as visibility, is a measure of how much and how far a wayfinder can see from a specific location. The higher the visibility of a location, the better its visual access is. Studies have shown that higher visibility potentially helps spatial orientation and wayfinding (Gärling, Lindberg, and Mäntylä, 1983). In the present study, it is important to note that areas formerly intended only to store books have been opened to public access (the Central Stacks). These areas have different characteristics than those designed with patrons in mind. 24 R. Li and A. Klippel Third, the complexity of the spatial layout is a little more difficult to define concisely. Aspects related to complexity are the size of the environment, the number of possible destinations and routes, and whether the routes intersect at right angles or not. The factors discussed above do not measure orthogonal (independent) environmental characteristics. It is likely that, for example, a simple layout increases visual access. In libraries, the layout created by book stacks (long rows of bookshelves and narrow corridors) increases layout complexity and decreases visibility at the same time. In general, it is important to understand the influences of different factors of physical environments on wayfinding behaviors. In the following section, we introduce the term space syntax, which is a summary term for multiple methods to quantitatively analyze physical environmental factors. Our particular approach allows us to compare different environments and link wayfinding behaviors to environmental characteristics. Space Syntax Originally a set of methods used in urban studies and social theory, space syntax has been adopted in wayfinding research to help understand the relationship between physical environments and wayfinding behaviors through formal, quantitative characterization of the environment. It is “one [way] of representing and quantifying aspects of the built environment and then using these as the independent variables in a statistical analysis of observed behavioral patterns” (Penn, 2003, 34). Space syntax has been modified for use in other disciplines to capture relevant aspects of physical environments. The most popular space syntax methods include isovists (Benedikt, 1979), axial maps (Hillier and Hanson, 1984), visibility graph analysis (VGA) (Turner et al., 2001), and interconnection density (ICD) (O’Neill, 1991). In the present study, the following space syntax methods are selected: axial maps, VGA, and ICD. They address three important and complementary aspects of environments previously discussed: visibility, connectivity, and layout complexity. Detailed explanations of each method and resulting formal descriptions of the library environment are provided in the results section. Space syntax has been used to correlate human wayfinding behaviors with indoor building characteristics. For example, Wiener and Franz (2004) asked participants to find the best indoor overview or hiding place. They found that either the best overview place or hiding place was directly related to the visibility of locations. Hence, space syntax, with its formal definitions of visibility, seems to be an effective analytical tool for predicting participants’ choices of indoor locations. Additionally, space syntax methods are able to shed light on participants’ indoor wayfinding strategies. Hölscher, Brösamle, and Vrachliotis (2006) used space syntax to correlate with Wayfinding in Libraries 25 individuals’ preferences for certain wayfinding strategies in a complex building. Wayfinders were more inclined to walk in areas where the connectivity of routes and visibility were higher. However, the correlation between space syntax analysis and spatial behaviors is questioned by some researchers. For example, Davies and Peebles (2010) found it problematic to predict orientation performance from two-dimensional spatial layout alone (as assessed by several space syntax measures). By using three space syntax measures as well as considering the role of signs not included in the assessment of space syntax, we hope to increase the potential for relating formal, quantitative characterizations of environments and spatial behaviors. To recap, space syntax provides quantitative descriptions of built environments based on their configurational information and potentially quantifies spatial intelligibility of a space, which is “the property of the space that allows a situated or immersed observer to understand it in such a way as to be able to find his or her way around it” (Bafna, 2003, p. 26). Although space syntax does not provide fully comprehensive descriptions of environments, it quantifies several aspects of the environment (e.g., layout complexity and visual access) that potentially contribute to understand wayfinding behaviors. In this article, we design a behavioral study to provide not only an assessment of wayfinding behaviors in a library but also additional insights into ways to predict wayfinding performance using space syntax methods. We complement an assessment of environmental characteristics with assessments of individual differences. The combination of both environmental and individual characteristics may provide a more accurate understanding of wayfinding behaviors in buildings. METHODS In this section, we describe the design of the behavioral study for assessing wayfinding performance in the library. Results are presented in the following section together with results of our space syntax analyses. Participants Considering that an individual’s familiarity with an environment might contribute to wayfinding performance in that environment, two groups of participants with different familiarity levels were recruited for the study. Four students who had visited the library at the beginning of the semester formed a group of participants with limited familiarity; a second group with four students who had never been to the library formed a group with no familiarity. 26 R. Li and A. Klippel Environment The study was designed to assess participants’ wayfinding behaviors in areas with different environmental characteristics. Three wings of the main library were selected: Paterno Library, Central Stacks, and West Pattee Library. There are two interesting characteristics of the three areas: they are connected only on the first floor and also within each area the number of floors is totally different. The floor plans of the main library are illustrated in Figure 1. Materials and Procedures The experiment was done with one participant at a time. Each participant met the experimenter at the lending services desk on the first floor of Pattee Library, and the experiment began when the participant gave his or her consent. First, the participant was asked to locate two books in Paterno Library, starting from the lending services desk. The two books were shelved on two different floors (2nd and 5th).When a participant had found these two books, he or she was asked to estimate in which direction lay the lending services desk. Once the tasks in Paterno Library were finished, the participant was given a second task of locating two books in the Central Stacks, again on two different floors (1A and 2A). Upon finishing this task, the participant was again asked to estimate the direction back to the same lending services FIGURE 1 Floor plans of the main library. The three wings, West Pattee, Central Stacks, and Paterno Library, are connected only on the first floor. (Courtesy of the Public Relations and Marketing Department, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University). Wayfinding in Libraries 27 desk, and then given a final task of locating two more books in West Pattee Library. Each participant was told to use whatever information he or she could find in the library to help locate the books. The experimenter followed each participant at a medium distance to give each participant a feeling of freedom in making wayfinding decisions. A Sony HandyCam video camera was used to record the entire wayfinding process. RESULTS Formal Descriptions of Environments Wayfinding in the library was not limited to just walking along the hallway. Within each library area, participants also had to explore the aisles created by the stacks arrangement. To analyze participants’ wayfinding behavior, locations of books, shapes of bookshelves, and the library floor plans were digitized. This allowed for quantitatively characterizing the environment using space syntax methods. We employed certain space syntax methods in this study to assess the factors of buildings that influence wayfinding behaviors. Thus we have organized this section into paragraphs about each of the three environmental aspects we focused on in this study: visibility, layout complexity, and connectivity. It is important to note that current space syntax methods do not cover signage, so a discussion of signage will be included separately in the discussion section. VISIBILITY The open-source software Depthmap (Turner, 2004) was used to carry out a systematic analysis of the visual access (visibility) of the three library areas. One major component of Depthmap, VGA, provides comprehensive analysis of the visual access of an entire floor regarding all accessible locations. Examples of visual access on library floors are presented in Figure 2. Results of VGA for Central Stacks 1A show poor visibility for the entire area with few exceptions. In contrast, results for Paterno Library fifth floor (5F) shows good visibility except for areas between bookshelves. West Pattee third floor (3F) show visibility similar to Paterno Library. Based on the introduction of visibility earlier, these differences in visibility among the Central Stacks, Paterno Library, and West Pattee can lead to different wayfinding performances. LAYOUT COMPLEXITY The layout complexity of the library areas was assessed by the ICD method, which uses the total number of intersections and the number of connected paths to the intersections in a building as a way to assess a floor’s layout 28 R. Li and A. Klippel FIGURE 2 Output of visibility graph analysis. From top to bottom: Central Stacks has very poor visibility while Paterno Library and West Pattee have good visibility. 29 Wayfinding in Libraries complexity. In our study, density is calculated by dividing the total number of paths by the total number of intersections. ICD, therefore, is a global measure of complexity that disregards individual decision points. For examples, see Figure 3, which shows the intersections and paths between intersections on Central Stacks 1A, Paterno 5F, and West Pattee 3F. The ICD of each floor is also shown. Because we considered the actual location of all book shelves in this assessment, we calculated the ICD based on all paths formed by bookshelves and the main path in each library. Our ICD results seem to correlate negatively with our VGA results in that low visibility areas seem to have higher layout complexity. It is thus reasonable to assume that a complex layout leads to poor visibility. CONNECTIVITY Connectivity, revealed in axial maps, was originally used to represent street networks in a less complex way. An axial map is “the least set of lines which pass through each convex space and makes all axial links” (Hillier and Hanson, 1984, 91–92). These lines, which can be treated as paths (or possibly chosen as routes) are called axial lines. Figure 4 shows the axial maps of the three library areas. The results of the axial map assessment show that areas of higher visibility tend to have higher connectivity and lower layout complexity, and vice versa. Wayfinding Performance WAYFINDING TIME Participants performed differently with respect to time spent in each booklocating task (Table 1). First of all, participants with different levels of familiarity showed varying performance. It was not surprising to see that participants with limited experience spent less time than participants with no experience to locate books in Paterno Library and West Pattee. It was surprising, however, that both groups of participants spent the most time overall, and almost the same time as each other, to locate books in the Central Stacks. These results show that wayfinding behaviors are related not only to the wayfinder’s familiarity but also to the physical structures of the buildings. Regardless of familiarity, participants tended to spend more time at areas TABLE 1 Average Time Spent in Each Library Area by Group (Mins) Group Limited experience No experience Paterno Library Central Stacks West Pattee 9.80 16.66 14.08 14.30 7.96 13.38 30 R. Li and A. Klippel FIGURE 3 Results of interconnection density (ICD) calculations. Central Stacks has the highest layout complexity while Paterno Library and West Pattee have lower layout complexity. Wayfinding in Libraries 31 FIGURE 4 Output of axial maps. Central Stacks has very poor connectivity while Paterno Library and West Pattee have better connectivity. 32 R. Li and A. Klippel TABLE 2 Extra Distances Walked in Each Library Area by Group and Length of Shortest Paths Group Paterno Library (m) Central Stacks (m) West Pattee (m) 132.24 179.45 94.96 179.95 217.60 29.71 144.11 142.07 58.25 Limited experience No experience Shortest path m = meter whose visibility and connectivity were low and whose layout complexity was high. EXTRA WALKING DISTANCES In general, the more time a participant spent in a library looking for books, the more distance he or she walked. The captured videos helped the authors trace each participant’s route and calculate the extra distance he or she walked by subtracting the shortest distance to locate a book from the actually walked distance (Table 2). Again, it was surprising to see that both groups of participants covered more distance in the Central Stacks, which, according to our previous results, was shown to have the highest layout complexity, lowest visibility, and lowest connectivity of all three library areas. POINTING ERRORS The pointing errors made by each participant in all three library areas are shown in Table 3. These data show a similar pattern compared with the time spent and extra distance walked in each library area. Both groups of participants had similar pointing errors in the Central Stacks. However, the pointing errors differ greatly between groups in the Paterno Library and West Pattee. It seems that in areas with low visibility, low connectivity, and high layout complexity, familiarity did not influence direction pointing performance as much as environmental characteristics. TABLE 3 Average Pointing Errors in Each Library Area by Group Group Limited experience No experience ◦ = degree Paterno Library (◦ ) Central Stacks (◦ ) West Pattee (◦ ) 45.00 78.75 70.00 75.00 23.75 95.00 Wayfinding in Libraries 33 ROUTE PATTERNS The routes walked by participants showed very distinct patterns. In the Central Stacks, no participant walked directly toward the location of the books. Instead, routes showed many detours and turns. The visibility and connectivity in the Central Stacks is the lowest and the layout complexity is the highest among all three library areas. It certainly can be considered the most difficult part of the library in which to orient oneself. In the other two library areas, participants walked toward the correct general location of the books, even though they had some difficulty locating the book at the local scale (at the actual shelf, where participants were mostly influenced by signage). Figure 5 shows the maps of all routes walked by all participants in the three library areas. In the following paragraph, we elaborate on the effect of signage on wayfinding performance. SIGNS Signs in the library serve a very important role in wayfinding. Signs help patrons confirm the location of themselves or books in all environments. This finding is reflected by the mistake patrons made in Paterno Library because of inconsistency of the signs. Routes on the fifth floor of Paterno Library showed that most participants bypassed the correct location of the book and went to a different bookshelf. This is due to inconsistency between the signs provided in the library, and the information participants found in the online library catalog. At this location, participants were looking for a picture book; picture books are part of the larger juvenile collection. Yet the catalog indicated only Juvenile; participants went directly to the bookshelf marked Juvenile instead of the one marked Picture Books. This finding demonstrates not only the importance of signage in libraries (Carr, 2006), but also shows the problems created by inconsistencies between the organization in the online catalog and the physical organization of books on a shelf. DISCUSSION Role of Visibility Locations where participants made wrong turns or hesitated to make wayfinding decisions had very low visibility. For example, at each entrance to the Central Stacks, participants could not see much information about the floor layout. Furthermore, no additional information was provided at these locations to give participants descriptions of collections on this floor. It was apparent that participants had difficulties at these points to make wayfinding decisions, lengthening the time spent looking for books and creating detours. All participants encountered these difficulties in the Central Stacks independent of their familiarity. 34 R. Li and A. Klippel FIGURE 5 Routes walked by participants in different libraries. Wayfinding in Libraries 35 In West Pattee and Paterno libraries, it appears that wayfinding difficulty was not as closely related to the environment as in the Central Stacks. First, visibility of the two areas is better than in the Central Stacks. Second, participants of the two groups showed varying wayfinding performance in the two areas. Here, familiarity seemed to play a more important role in explaining wayfinding difficulties than in less complex environments. Role of Layout Complexity Layout complexity was inversely related to visibility and connectivity in this study; areas with high layout complexity had low visibility and low connectivity. Layout complexity showed slight differences in its relation to wayfinding performance as compared to visibility. First, layout complexity seemed to correlate with the time participants spent in each area. Regardless of familiarity, participants spent the most time where layout complexity was highest. Second, pointing errors did not represent a simple relationship with just visibility, but also depended upon layout complexity (which further depended on participants’ familiarity). To participants who had limited familiarity, the areas with the highest visibility were related to the smallest pointing errors. To participants with no familiarity, the areas of the highest layout complexity were related to the largest pointing errors. Layout Complexity vs. Familiarity Analysis of layout complexity against familiarity revealed an interesting pattern across the three library areas. The time spent by participants was longer and the distances walked were longer in areas where layout complexity was higher (in the Central Stacks). The pointing errors also implied that areas of higher layout complexity add more difficulties to pointing tasks. Hence layout complexity played a much more important role than familiarity in this area. However, in Paterno and West Pattee, where layout complexity was lower, individual familiarity with the environment played a more important role than layout complexity. This finding is in contrast to earlier suggestions that familiarity plays a more important role than layout complexity in wayfinding performance (O’Neill, 1992). Further assessments are necessary to clarify the different influences that layout complexity and familiarity have on wayfinding. CONCLUSION This study demonstrated that wayfinding behaviors can be correlated with both characteristics of physical environments and individual differences. Methods of space syntax are effective in quantifying certain aspects of 36 R. Li and A. Klippel physical environments and relating them to human wayfinding behavior. This can provide valuable insight for designing and improving wayfinding systems in libraries and for assessing problematic areas without the need to perform user studies. The major finding in this study is the confirmation of the relationship between aspects of environments (i.e., visibility, connectivity, and layout complexity) and human wayfinding behavior. More importantly, this study investigated factors of physical environments in libraries that impact wayfinding behaviors. Previous studies pointed out the potential relations of choices of places in buildings and visibility (Wiener and Franz, 2004). We used three different space syntax methods to address different aspects of buildings. In addition to these aspects of environment, signs and maps in the library influence the accuracy of locating books. Signs and maps are the most effective and simplest way to improve wayfinding in areas like Central Stacks whose visibility and connectivity are low while layout complexity is high. The important role of signs is demonstrated in our experiment that even in areas with high visibility, high connectivity, and low layout complexity, a misleading sign made participants choose the wrong bookshelf in which to locate a book. Furthermore, wayfinding difficulties are due not only to the environment but also to the familiarity of the wayfinder with that environment. We suggest that both environment and familiarity have different weights in influencing wayfinding performance. The layout complexity of an environment may be the most influential factor of wayfinding behaviors.1 When an environment has a high layout complexity, all wayfinders have difficulties regardless of their familiarity. However, when the environment is less complex, the familiarity of the environment is then the major factor affecting wayfinding performance. This study presents the different wayfinding performances in libraries such as time spent and extra distance walked in relation to layout complexity. For revealing and predicting wayfinding problems that exist in libraries, it is beneficial to combine methods that address both the quantitative assessment of physical environments and allow for evaluating individual behaviors. Similar studies have also showed the effectiveness of using tools of spatial science to understand wayfinding behaviors (Mandel, 2010). Slightly different from Mandel’s study, which considered only the entry areas of a library, we addressed the areas where patrons have the most difficulty—areas where books are shelved—to reveal the wayfinding difficulties resulting from different aspects of the environment. To suggest effective wayfinding systems to help patrons more easily find their way, all aforementioned factors should be considered. The design of wayfinding systems should be tailored to the specific characteristics of areas. For example, Central Stacks in this study needs more attention to overcome the difficulties caused by its low visibility, low connectivity, Wayfinding in Libraries 37 and high layout complexity. In this case, using simple maps that provide patrons a quick glimpse of the layout is an effective improvement. In addition, signs at important locations such as the entrance to Central Stacks and major intersections in the stacks should improve the wayfinding systems. We have reported these findings to the administrators of the University Libraries to initiate improvement of wayfinding systems. For example, to overcome the shortcoming of areas with low visibility, low connectivity, and high layout complexity that lead to patrons’ greater mental efforts, signs and maps are more effective and implementable than is changing the physical structure of a floor. The administrative team has made efforts to redesign signs and provide simpler floor maps to help patrons learn the areas in the library in a timely and effective manner. We continue working with the library to assess additional factors such as the global and local aspects of environment and the hierarchy of wayfinding behaviors to enrich our understanding of wayfinding in the library. To sum up, this study signifies the importance of using approaches from multiple disciplines to investigate the wayfinding problems at the theoretical level. At the empirical level, it signifies the necessity of designing tailored wayfinding systems and extending these findings to other public buildings. NOTE 1. The layout complexity in this study is associated with visibility and connectivity. Here we use high layout complexity to indicate low visibility and connectivity in library areas. REFERENCES Bafna, S. 2003. Space syntax: A brief introduction to its logic and analytical techniques. Environment and Behavior 35(1): 17–28. Benedikt, M. L. 1979. To take hold of space: Isovists and isovist fields. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 6(1): 47–65. Carr, A. R. 2006. An experiment with art library users, signs, and wayfinding. Chapel Hill, NC: School of Information and Library Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Davies, C., and D. Peebles. 2010. Spaces or scenes: Map-based orientation in urban environments. Spatial Cognition & Computation 10(2): 135–156. Evans, G. W., M. A. Skorpanich, T. Gärling, K. J. Bryant, and B. Bresolin. 1984. The effects of pathway configuration, landmarks and stress on environmental cognition. Journal of Environmental Psychology 4(4): 323–335. Gärling, T., E. Lindberg, and T. Mäntylä. 1983. Orientation in buildings: Effects of familiarity, visual access, and orientation aids. Journal of Applied Psychology 68(1): 177–186. 38 R. Li and A. Klippel Hillier, B., and J. Hanson. 1984. The social logic of space. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Hölscher, C., M. Brösamle, and G. Vrachliotis. 2006. Challenges in multi-level wayfinding: A case-study with space syntax technique. Paper presented at Spatial Cognition ‘06 Space Syntax and Spatial Cognition Workshop, Bremen, Germany. Klippel, A., C. Freksa, and S. Winter. 2006. The danger of getting lost: YAH maps in emergencies. Journal of Spatial Sciences 51(1): 117–131. Levine, M. 1982. You-are-here maps psychological considerations. Environment and Behavior 14(2): 221–237. Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Mandel, L. H. 2010. Toward an understanding of library patron wayfinding: Observing patrons’ entry routes in a public library. Library & Information Science Research 32(2): 116–130. Meilinger, T., C. Hölscher, S. J. Büchner, and M. Brösamle. 2007. How much information do you need? Schematic maps in wayfinding and self localisation. In: Spatial Cognition V: Reasoning, Action, Interaction, Barkowsky, T., M. Knauff, G. Ligozat, and D. R. Montello (Eds.), Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. O’Neill, M. J. 1991. Evaluation of a conceptual model of architectual legibility. Environment and Behavior 23(3): 259–284. O’Neill, M. J. 1992. Effects of familiarity and plan complexity on wayfinding in simulated buildings. Journal of Environmental Psychology 12(4): 319–327. Penn, A. 2003. Space syntax and spatial cognition: Or why the axial line? Environment and Behavior 35(1): 30–65. Shepard, R. N., and S. Hurwitz. 1984. Upward direction, mental rotation, and discrimination of left and right turns in maps. Cognition 18(1–3): 161–193. Strube, G. 1992. The role of cognitive science in knowledge engineering. In: Contemporary knowledge engineering and cognition, Proceedings of the First Joint Workshop on Contemporary Knowledge Engineering and Cognition. London: Springer-Verlag. Turner, A. 2004. Depthmap 4, A Researcher’s Handbook. London: Bartlett School of Graduate Studies, University College of London. Turner, A., M. Doxa, D. O’Sullivan, and A. Penn. 2001. From isovists to visibility graph: A methodology for the analysis of architecture space. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 28(1): 103–121. Warren, D. H., and T. E. Scott. 1993. Map alignment in traveling multisegment routes. Environment and Behavior 25(4): 643. Wiener, J. M., and G. Franz. 2004. Isovists as a means to predict spatial experience and behavior. In: Spatial Cognition IV: Reasoning, Action, and Interaction, Lecture Notes of Artificial Intelligence. Freksa, C., M. Knauff, B. Krieg-Brückner, B. Nebel, and T. Barkowsky (Eds.), Verlag Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. Copyright of Journal of Map & Geography Libraries is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. View publication stats