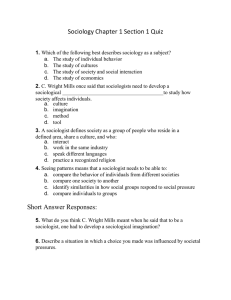

Sociological Imagination: Teaching with Everyday Objects

advertisement

1 References Peter Kaufman (1997). Michael Jordan Meets C. Wright Mills: Illustrating the Sociological Imagination with Objects from Everyday Life. Teaching Sociology, 25(4), 309–314. doi:10.2307/1319299 Description, Local Analysis, Global Analysis, Historical Analysis #Conclusion & Recommendation Three primary strengths of this exercise are: (1) providing an applied example of the sociological imagination; (2) offering a stepby-step approach to thinking critically about social life; and (3) providing a reference point to build upon when introducing new topics throughout the semester. In this sense, the exercise is ideal for the introductory course. Students have no problem grasping the exercise and they quickly become comfortable using the perspective of the sociological imagination. I have also used this exercise while teaching other classes with equal success although in these instances the topic of the course constrains the choice of the object. The use of this exercise also provides a number of options for evaluative work. As an end of the semester project, I have broken the class into small groups and let each group choose their own object. They then must do the exercise as a group and present their findings to the class making reference to at least four of the topics discussed during the semester (e.g., race, culture, collective behavior, health). Another option is to assign research projects based on the global and historical responses given in steps three and four. For example, students may do research papers on topics such as: "The Influence of American Products in the Third World;" "The Popularity of Basketball in the Inner Cities;" "The Rise of the Black Athlete From Jessie Owens to Michael Jordan; " and "Changes in the Fashion Industry: Have High Tops Replaced High Heels?" According to Mills, the real analyst of the social world is able to recognize both the task and the promise of the sociological imagination; she or he understands how personal biography intersects with history to inform the social reality. For beginning students, this can be extremely difficult to comprehend. Without an adequate example to illustrate Mills' idea, most students leave the introductory class with only a vague and abstract understanding of this insightful concept. By using objects from the everyday lives of students, this exercise provides a concrete and easily understood example of the intersection between personal biography and history. In short, the exercise helps students begin to grasp the sociological imagination and become real social analysts in true Millsian fashion https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-sociological-imagination9780195133738?cc=ph&lang=en# The sociological imagination Mills calls for is a sociological vision, a way of looking at the world that can see links between the apparently private problems of the individual and important social issues. Dandaneau, S. P. (2009). Sisyphus had it Easy: Reflections of Two Decades of Teaching the Sociological Imagination. Teaching Sociology, 37(1), 8–19. doi:10.1177/0092055x0903700102 The last place one would want to attempt to transform everyday consciousness into sociological selfconsciousness #3 The received interpretation of Mills is that he is a sociological conflict theorist (e.g., Andersen and Taylor 2006; Collins and Markowsky 2007). In this view, Mills’s werk is understood to have addressed asymmetries of power and the conflicts which result within modern society. The “plain Marxism” and The Causes of World War Three (1958) and Listen, Yankee! (1960a) mass circulation pamphlets of his later years notwithstanding, Mills’s intellectual debt is thought primarily to accrue to Max Weber (via Hans H. Gerth at the University of Wisconsin) and to Thorstein Veblen (via Clarence Ayers at the University of Texas at Austin). In this reading, Mills abandoned sociology in favor of a career as a political activist, the result of various and mostly tragic personal peculiarities (see Horowitz 1983). Despite his idiosyncratic lifestyle, Mills’s portrayal of the “sociological imagination” still sits comfortably (or, at least not uncomfortably) within the mainstream of the discipline. After all, The Sociological Imagination (and its companion volume, Images of Man [1960b]) advocated fidelity to sociology’s “classic tradition” and, in particular, to its theoretical emphasis on the explanatory power of social structure. Indeed, it is commonplace for pedagogical renderings of the sociological imagination to explain its significance primarily in terms of Mills’s own posited distinction between “private trouble” and “public issues,” where public issues are defined as the consequence of institutional arrangements and, thus, are the principal focal point for sociology (1959:8-11). But this interpretation, correct as far as it goes, relies on The Sociological Imagination’s first pages at the expense of the remaining two hundred. Thus conceived, the sociological imagination and a budding career in the welfare state bureaucracy are simpatico. Thus reduced, the sociological imagination is that which helps one read the newspaper intelligently. In my view, the key to Mills’s distinctive theoretical approach is his attention to totality, which he conceives philosophically and generally as the emergent projection of the sum of mediation between every biography and every institution in on-going societies both past and present the world over (Dandaneau 2001). Mills was thus a realist, but he knew that an actually existing comprehensive body of knowledge, even via an ambitious comparative sociology, was impossible to ever collect and represent. Not only is this goal wholly impractical, it is also theoretically impossible. The so-called object of sociology does not stand outside of time and apart from our efforts to know it. Mills was a realist, but he was not a philosophical positivist nor did he shy away from postmodern experimentation with nonrealist modes of representation. In Mills’s view, what was needed most of all was the cultivation of theoretical imagination, empirically disciplined and conceptually rich and enriching imagination, but imagination, nonetheless. Mills’s realism was always already philosophically pragmatic in its orientation, and “orientation” was the grail which he sought with every printed word. In a view that I believe is consistent with Mills’s own, I argue that the absence of sociological consciousness leaves the individual’s sanity in danger of collapsing into cynicism in one direction and panic in the other. In the former, the individual is impervious to social experience (think “crackpot realism” [Mills 1958]), whereas in the latter the self is drowned in postmodern excess (which Mills [1959] intimates when he addresses the growing threat of a “deadly unspecified malaise” [p. 11]). Uprichard, Emma (2012). Being stuck in (live) time: the sticky sociological imagination. The Sociological Review, 60(), 124–138. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954x.2012.002120.x Mills was very clear that in order to deliver the promise of the sociological imagination, which helps to free each and every one of us from feeling trapped, it is necessary to turn to ‘biography, history, society as coordinates of a well-considered social study’. Indeed, it is precisely in Mills’ three-point hinge-pin that we see the severity of the ‘fault-line’ within the emerging ahistorical digital research critiqued here – a faint but visible crack that risks being serious if ignored in the long run. One might indeed agree with Mills, therefore, that the relevancy of history is dependent on context. As he goes on to explain, ‘Everything, to be sure, may be said always to have “come out of the past” but the meaning of that phrase – “to come out of the past” – is what is at issue’ (Mills, 1959: 173) Mills was also all too aware of the ‘social’ nature of time, and of the construction of history in particular. Indeed, he goes as far as saying that this feature of time’s relevance – i.e., time’s relevance as socially constructed in historical context – is likely to be positively detrimental to the sociological imagination. ‘Now-casting’ arguably turns the promise of the sociological imagination on its head. After all, whilst it is possible to argue that Mills was inflating the importance of history, the key reason for him doing so was ironically because he was all too aware of how important a role history plays in shaping the future. The conception and perception of the relevancy of history – ie ‘the principle of historical specificity’ – was precisely what Mills understood to be at the core of the sociological imagination. Kemple, T. M.; Mawani, R. (2009). The Sociological Imagination and its Imperial Shadows. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(7-8), 228–249. doi:10.1177/0263276409349283 Whether viewed as a style of thought or a moral impulse, a scientific discipline or an aesthetic sensibility, the sociological imagination must find its way between recurring moments of opacity and insight. In Mills’ use of these commonplace visual metaphors, successfully cultivating this faculty entails ‘the capacity to shift from one perspective to another’. The ‘close-up scenes of job, family, and neighborhood’, for example, must be viewed through the wide-angle lens of economic institutions, fluctuating divorce rates and the spectacular structures of the big city. Conversely, the ‘longer view’ of historical and structural transformations remains the abstract assumption of a vicarious ‘spectator’, unless one can also take a magnified and microscopic look at how these transformations are experienced personally and in everyday life (Mills, 1959: 7, 3). What is needed, then, is the ability to hold these contrasting perspectives in view, either in succession (‘cinematically’) or simultaneously (as ‘snapshots’). #3 In Figure 1 we schematize one of Mills’ most celebrated and cited theoretical and methodological arguments in terms of the ocular imagery he employs to elaborate it: ‘Perhaps the most fruitful distinction with which the sociological imagination works is between “the personal troubles of milieu” and “the public issues of social structure”’ (Mills, 1959: 8). Here his ‘bifocal’ view of social life is depicted in the shape of a relatively recent and now widely accessible invention, which Benjamin Franklin is said to have designed in order to enhance the ability to see things clearly which are both near and far away. According to this visual analogy (the cultural significance of which would not have escaped Franklin), if in some sense we have lost our capacity – or lately discovered our inability – to understand our personal milieus in light of the expanding social structures which envelop them, then a prosthetic device is needed to correct and clarify this distortion-effect (White, 1999). The figure traced here suggests that ‘private troubles’ are distinct from yet connected to ‘public issues’, at least as long as they are not framed too broadly as social – or too narrowly as psycho - logical – ‘problems’. What we are calling Mills’ ‘sociological bifocals’ is therefore also a ‘binocular’ technology insofar as these corrective lenses facilitate a differentially magnified quadruple focus on reality – two longer telescopic views plus two close-up microscopic angles – as well as alternating perspectives which produce a parallax view – the apparent displacement or difference of orientation of an object when seen along two different lines of sight. This way of picturing the sociological imagination helps to expose the scientistic fiction of disciplined observation, according to which a realistic representation hides or ignores the embodied stance of the spectator, as in the conventional view of a scientific account presented as an objective mirror or window on reality (Wilson, 2004). In this depiction we draw attention instead to the necessarily framed and partial character of ‘seeing sociologically’, that is, to the relatively arbitrary, artificial, constructed and situated aspect of observation, which facilitates some views and ways of knowing while suppressing or restricting others. #Conclusion In the end, it seems that Mills was more attuned to the conditions of the performance of sociological thinking than to the fate of its products, and thus he was more concerned with its character as poetry and as politics than with its status as a profession or personal confession (see Abbott, 2007). Nevertheless, he worried that the sociologist may risk becoming the main subject of his own account, just as the artist may get in the way of what he is trying to show and tell, each projecting more of an artificial self-portrait than a realistic ‘photograph’ (Mills, 2008 [1948]: 35). Lost would be any sense of the public urgency and social relevance that we need to address the most pressing problems of the day: how many, who, and what are we? (the question of metaphysical multiplicity) and how can we live together? (the question of ontological unity) (Latour, 2005: 247–62). By bringing these questions under the twin signs of ‘sociology’ and ‘imagination’, he challenges us to think within and act against a political, intellectual and historical legacy which often tends to distort clear vision and silence critical speech. Hironimus-Wendt, R. J.; Wallace, L. E. (2009). The Sociological Imagination and Social Responsibility. Teaching Sociology, 37(1), 76–88. doi:10.1177/0092055x0903700107 Sociologists have historically argued that social problems are socially created—that human agency creates social problems. We routinely teach our students that social issues are not the result of bad choices made by a subset of misguided individuals, nor the result of natural forces beyond our collective control. Social issues arise when dysfunctional social arrangements (environments) limit the range of choices available to individuals into either a subset of primarily bad choices, or no good choices at all. The realization that social problems are socially created should be a good thing—after all, if human agency creates social problems, then by logical inference social problems can be resolved socially through human agency guided by sociologically informed social policy. #2 A SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OF THE RESPONSIBLE SELF Mills ([1954] 1963) viewed the liberal education experience as involving the explicit and intentional training of students so as to develop their sensibilities, which he argued to represent the ability to make connections between social values on the one hand, and the practical skills necessary to achieve those desired value-laden relationships in society. As a student of Weber, it seems reasonable to suggest by sensibilities, Mills partly intended Weber’s concept of verstehen, or empathetic understanding. Mills ([1954] 1963) believed academics have a responsibility in academia for explicitly working to develop within all students the knowledge, skills and dispositions necessary for improving the social and communal circumstances of those suffering from conditions they do not understand and are unable to change. Similarly, an overarching goal of the higher education experience must be the development of a sense of social responsibility in all students. Furthermore, like Mills (1959), we believe sociology is particularly well suited for helping students develop their sensibilities and social responsibilities toward others, given the centrality of sociology among the social sciences. In particular, community-based social engagement represents the most promising pedagogy for helping students develop a sense of empathy with diverse others—a sense of connectedness resulting from the sharing of experiences and/or circumstances. A social-psychological foundation for thinking about the development of social responsibility in students can be found in the works of Cooley ([1902] 1964, [1909] 1962) and Mead (1934). Both are primarily recognized in our introductory courses for their theses that self-concepts are social constructions. Both point out that our awareness of who we are (i.e., “the self”) is continually developed and negotiated through social interactions with others. This social self represents both our personal perceptions of who we are, and an awareness of who we believe we are in the eyes of others. As argued by both theorists, our conceptions of self are principally developed in intimate associations (e.g., Cooley’s primary groups). In his thesis on the looking-glass self, Cooley ([1902] 1964) argues our sense of self-worth is directly determined by the reactions of others, from whom we seek approval or respect. Implicit in Cooley’s thesis is an innate need to be loved. Only with this theoretical assumption does it make sense that individuals would be concerned with how others react to our assertions of self and why, over the life course, individuals would continually adjust their self-presentations during interaction with others. In other words, how we think others perceive us matters equally in the creation of self-awareness. We also believe that in the contemporary era, the residential college experience is particularly well-suited toward the development of this sense of social responsibility toward a generalized other in young adults. As children leave their families of origin and become semi-independent adults living apart from their parents, they become new members of a larger community of unknown peers. As such, they are in a new and unique situation in which to intentionally explore the generalizable sense of obligation towards a general community at large. DISCUSSION: RECAPTURING MILLS’S PROMISE For Mills (1959), the goals of social science education were twofold: the creation of educated, self-regulating individuals, and to restore reason and freedom to their proper place in society (p. 186). The objective clearly prioritizes the immersion of students in communal processes and environments beyond our campus walls. After all, social theories are, at most, simplified approximations of more complex social realities. Our classroom discussions analyze how the rich have gotten richer while the poor are becoming poorer; the feminization of poverty; academic achievement differences by ethnicity; the underfunding of urban and rural schools; the failure to provide a community based network of care for those living with mental illnesses following deinstitutionalization, etc. Discussions of public issues such as these become more meaningful when our students can actually identify with them. 2 References B. Bernstein (1958). Some Sociological Determinants of Perception: An Enquiry into Sub-Cultural Differences. The British Journal of Sociology, 9(2), 159–174. doi:10.2307/587912 Chaiklin, H. (2011). Attitudes, behavior, and social practice. J. Soc. & Soc. Welfare, 38, 31. Greene, Joshua (2003). Opinion: From neural 'is' to moral 'ought': what are the moral implications of neuroscientific moral psychology?. , 4(10), 846–850. doi:10.1038/nrn1224 Rustin, M. (1963). The relevance of mills’ sociology. New Left Review, 1(21), 19-25.