The Process of Conflict Escalation and Roles of Third Parties

advertisement

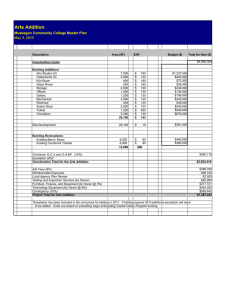

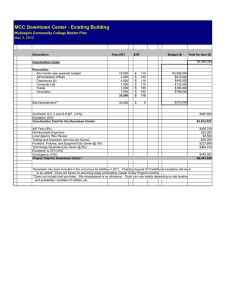

6 THE PROCESS OF CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES Friedrich Glasl Theory and practice of conflict handling by third parties present various approaches for the resolution of conflicts-for example, judicial conflict solving, arbitration, conciliation, mediation, good services, power intervention, process consultation, and so forth (Fisher, 1972; Young, 1972; La Tour et al., 1976; and Prein, 1976, 1979a). Many of these approaches may be compared and evaluated to arrive at some conclusions on the use of specific conflict-handling models for different kinds of social conflicts and different degrees of intensity of conflicts. However, what are different degrees of intensity? Which approach is appropriate for which degree of escalation? To answer these questions, this paper will present a model of escalation of social conflicts within organizations. The model of escalation describes various mechanisms at work and distinguishes nine different stages of escalation. Different strategies of conflict handling then are related to these nine different stages of escalation, and the relative value of conflict-handling interventions is discussed in light of the nine stages of escalation. The evaluation of these approaches suggests that all of them do have limited use and effect for specific stages but must be applied according to the degree of intensity of conflict. 119 G. B. J. Bomers et al. (eds.), Conflict Management and Industrial Relations © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 1982 120 FRIEDRICH GLASL INTENSITY OF CONFLICTS Many authors are searching for specific indicators to determine which strategic model may be appropriate for which degree of intensity. Fisher (1972) states that process consultation is not effective in less intense conflicts because it tends to make simple conflicts more complex rather than helping to solve them. Filley (1975) presents a model that in practice proved to be very helpful in less intensive conflict situations but insufficient in more escalated conflicts. Walton (1969) and Mastenbroek (1979) recommend methods of process consultation-similar to those developed by Blake, Shepard, and Mouton (1964)-in rather intense conflicts. Both authors emphasize that their methods may not be effective in considerably tough and tense situations. Douglas (1957), Walton (1969), Thomas (1976), and La Tour et al. (1976) recommend the use of mediation tactics for more intensive conflicts, and in later stages, methods of arbitration, and so forth. A more precise distinction of various degrees of escalation seems to be relevant for third parties to determine their course of action. Yet all guidelines given by these authors are still unpolished and general and do not provide sufficient criteria for third-party interventions. To this end, this paper will present a consistent model of conflict escalation developed both in research work on conflict processes and in the practice of external and professional conflict consultation for many organizations. This model of escalation is one of the most important diagnostic concepts. It helps us observe the relevant signs and symptoms of conflicts and to understand the dynamic forces at work that intensify a conflict and make it more and more complex and "poisonous." Knowledge of the dynamics of escalation and of the different stages of escalation thus serves to determine the appropriate course of action for third parties. The following sections outline the nine stages of escalation and relate some of the most relevant strategies and role models for conflict handling to these stages of escalation. Then the general findings of our model are modified as applied to two different basic types of conflicts. The issues of a conflict may be related to different types of mutual dependencies of the parties. The resulting distinction will clarify some of the seemingly contradictory findings of various authors. It can then be seen that they are not contradicting each other but relating to different basic situations that require basically different approaches. The purpose of this paper imposes some limitations on the presentation and discussion of our models. More details, research findings, and practical examples, as well as tools for diagnosis and intervention, are elaborated in my recent book on conflict management (Glasl, 1980). CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 121 DYNAMIC MECHANISMS OF ESCALATION Most theories on escalation deal with international conflicts. Wright (1965) differentiates four levels of escalation according to the use of violence between nations. In his theory, escalation starts with the parties' awareness of inconsistencies (stage one). At stage two, tensions are growing and hindering normal interaction between the parties. At stage three, the parties make use of nonmilitary means of pressure. They engage in openly violent activities at stage four. The main merit of this model is that it gives insight into the dynamic forces and mechanisms of escalation rather than the different stages. These elements are further developed by other authors-for example, Rapoport (1972), Deutsch (1973), and Thomas (1976). Pondy (1967) has developed a similar model of escalation. It can be applied to social conflicts between nations and between, for example, departments within an organization. Pondy describes the growing intensity of conflicts in these stages: (1) latent conflict, due to scarcity of resources, unclear job descriptions, contradictory goals, of a company, and so forth; (2) perceived conflict-that is, the parties become aware of existing tensions and antagonisms; (3) involvement of emotions of the parties, not mere perceptions and cognitions, (4) manifest conflict, in which the parties try to influence each other and thereby infringe upon or frustrate each other and which results in aggressive, violent, or destructive behavior; (5) aftermath of conflicts-that is, some changes of sources of conflict that lead to stage one. However, these stages may also lead to consecutive episodes of conflict. Pondy describes the growing awareness of conflicts but does not discern various stages once the parties have engaged in overt acts of violence. Our model of escalation distinguishes nine stages of overt conflict behavior, of changing perceptions and attitudes of the parties involved, and of qualitatively different patterns of interactions between the parties. Kahn (1965) has elaborated the most detailed process model of escalation of international relations in the thermonuclear age. It proceeds from latent tensions to perceived conflicts and from nonmilitary violence through means of traditional military power to the use of most advanced thermonuclear violence. Kahn discriminates forty-four steps of escalation that stem from quantitive degrees of violence made possible by highly technological warfare. His model is less suitable for the analysis of intraorganizational conflicts because the differentiated machinery of physical power is-fortunately-not available to the parties of organizational conflicts. However, Kahn's model of rungs and thresholds that mark all levels of escalation can easily be applied to conflicts within all kinds of organizations. Pondy 122 FRIEDRICH GLASL (1967), Walton (1969), Thomas (1976), and others characterize the nature of escalation processes as "spiraling" processes. One incident can give rise to negative sentiments that may foster aggressive behavior and thus start a new cycle of conflict behavior. Escalation reinforces negative perceptions, attitudes, and behavior and generates a new conflict episode. So conflict becomes a self-propelling process that generates its own resources of energy. The more a conflict escalates, the more it provides its own traps, which multiply and intensify existing tensions. Senghaas (1971) calls the nature of escalation processes a "pathological learning process" that increases dysfunctional behavior of the parties. Escalation gathers its own momentum. Once started, it is easier to intensify it than to stop or cure it. It requires a tremendous effort of consciousness, courage, and firmness in order to break through the vicious circles of escalation mechanisms. The following basic mechanisms-as primarily mentioned by Thomas (1976)-foster escalation and at the same time are increased in return by the other mechanisms described here. These mechanisms form a network of mutual causality tied together by vicious circles that reinforce each other. The most important of them are listed here: 1. Escalation increases projection mechanisms (Newcomb, 1947; 2. 3. 4. 5. White, 1966) and is increased by them while the parties engage more and more in acts of self-frustration. The conflict moves from the original issues to others, thus increasing the "issue complexity" of conflicts (Schelling, 1957; Thomas, 1976), while at the same time the parties' cognitive capacity to deal with complexity decreases at the same rate (Boulding, 1957; March and Simon, 1958; Holsti, 1970; Janis, 1972). The social complexity grows because the parties try to make others support their case; systems of coalition and alliances (Walton, 1969; Thierry, 1977) are built up and contribute to a generalization of conflicts-while at the same time the parties tend to personalize more and more (Filley, 1975). As a reaction to the growing complexity of the conflict, the parties adhere to a simplified model of cause-and-effect relationships regarding the conflict, where they see only one problem and only one main source-namely, the other party. The parties expect the worst from the other side and prepare to fight it (Frei, 1970; Milburn, 1977). This expectation provokes the worst of possibilities, thus causing the exact behavior in the other party that they should try to prevent (Cofer and Appley, 1964). CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 123 Paradoxically, the parties foster the very actions they are afraid of. This explains why the parties lose entire control of their behavior and, as a result, control of the conflict situation. Nevertheless, they tend to consider the other side fully responsible for the effects of its behavior. Escalation of conflicts is a process that moves from step to step, from less intense and less complex situations to more intense and increasingly complex situations. For a while a conflict shows the signs of a particular stage of escalation, and the parties do not risk provoking further escalation. They experience a definite threshold: Each stage of intensity is marked by specific qualities. Once a party has transgressed such a threshold, the conflict moves to a deeper level of violence, to the next stage of escalation. However, the parties again try to avoid further escalation. Temporarily, the conflict is under some kind of control and does not escalate further as long as the parties see clearly what will happen beyond the next threshold. Kahn (1965) describes the implicit formulas of some thresholds-for example, "Don't rock the boat!" or "Don't risk unlimited war!" The most important analysis of the nature of these thresholds as "focal points of expectation" is given by Schelling (1957, p. 29). He mentions landmarks in a conflict that have clear symbolic meaning to the parties. Thus, the parties need not negotiate about these "focal points"; they share an implicit consensus on them. In our model of escalation, these thresholds can be compared to "dikes." The flood may rise and rise. Only when it overflows the dikes or when it breaks them does the conflict enter a new level of escalation. The next section describes some of the main characteristics of each stage of escalation. Step by step the conflict enters the realm of more unconscious and subconscious forces in human beings and in social institutions and adds new, uncontrollable energy to the existing conflict. Therefore, we symbolize the escalation process not as climbing up a ladder, as Kahn does, but as a boat floating more and more quickly down a river from one rapid to another (see figure 6.1). It is easy to float downstream with the current, but it requires a tremendous effort to row against the stream. This is the kind of energy required for conflict-handling intervention. STAGES OF ESCALATION Our model of escalation, as shown in figure 6.1, distinguishes three main phases. Each phase consists of three stages separated by thresholds or "points of no return." 124 FRIEDRICH GLASL Stages 1 /. ~2 ~3 ~4 V~ I I Thresholds I Thresholds I Main phase I FIGURE 6.1. I I Main phase II I I I Main phase III Stages of escalation and thresholds Main Phase I The parties are aware of the latent and manifest tensions and antagonisms but try to treat them in a rational and controlled way. During the course of escalation, they experience many hindrances that originate from the parties rather than from the objective sources of conflict. Efforts to solve the conflicts are still made in some cooperation with the other party and deal mainly with impersonal aspects, such as organizational structures, procedures, materials, and methods. During the first three stages (main phase I) one can clearly see an increase of issue complexity and reduction of cognitive complexity. The most obvious features of the three substages are described below. Stage one: attempts to cooperate and incidental slips into tensions and frictions. During discussions the parties realize that sometimes opinions and proposals become crystallized and fixed. People tend to defend rigid positions and to persuade others to share their ideas. Now the parties realize that they must not take consensus and cooperation for granted, but that these must be maintained by sacrifices. Once a party is not willing to cooperate, deadlocks and hard confrontations may follow and block the parties from any further progress of discussions or negotiations and bargainings. They start closing ranks. A so-called skin-formation process begins and separates the parties psychologically from each other. That "skin" acts as a filter for further communication; selective inattention CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 125 (Blake and Mouton, 1961) distorts the parties' view of each other and of "objective reality." Also, a process of "role crystallization" (Guetzkow and Gyr, 1954) starts: People are pushed to fulfill certain role expectations that seem to be useful in defending one's position. These role concepts become confirmed and stabilized during the conflict process. The total picture of stage one is very much like the "normal" group sessions in many organizations. Once groups become aware of some obstacle in their interaction, they try harder to fight these hindrances. However, very often fighting creates additional irritation and fosters dysfunctional behavior. Still, the motivation of the parties is dominantly cooperative, although it becomes mixed with slight competitive features. Stage two: polarization and debating style. After the first tensions and frictions, the parties give evidence of mixed motives (Deutsch and Krauss, 1962). They work for both cooperation for solving their common problems and for competition in order to defend their own social position and their convictions. The parties begin to perceive each other as subjects of different value. Each one considers itself as being slightly superior and treats the other side as being of some inferior quality. This is manifested in the parties' behavior. It causes further irritation because each party wants to demonstrate that it is superior to the other, or at least of equal value. A struggle for "equity" (Diesig, 1961) starts, which easily turns into a fight for superiority, although at this stage it does not yet result in domination and suppression. Each party tries to show that it adheres to the better position and uses better arguments to put it forward. They confront each other with extreme dilemmas (e.g., "either red or dead," "either conservative or progressive") with no shades in between. Positions become polarized. The parties use a wide range of unfair tricks and tactics that make the parties believe their positions are irreconcilable. Discussions turn into debates in which each side is only concerned with impressing the other side or the audience rather than with listening to the arguments of the opponent. A debate seems to be a competition of logical reasoning. Yet in reality many irrational tactics are used, as described by Thelen (1954), van Hoesel (1957), Gelner (1967) and Rother (1976). For example: • • One attacks the other party personally in order to achieve a weakening of its intellectual position. One exerts emotional pressure on the other side ("Attack the man and you will get the ball!"), although one pretends to adhere strictly to rules of fair play. 126 FRIEDRICH GLASL • One uses faults of logical reasoning in order to mislead the other party. One exaggerates the other party's position and subsequently attacks that position as being very extreme and unrealistic. • A debate is, by its real nature, a kind of intellectual violence. Still, the parties are convinced that they may solve their differences by employing mainly intellectual and verbal means. At the same time the parties experience a growing discrepancy in their verbal communication: they pretend to behave correctly and logically, but their real intention-the "undercurrent"-is different. As a result, though the parties start doubting the meaning of verbal expressions, they still have to rely on them. Stage three: deeds, not words. Now the attention moves from verbal combat to deeds. The parties stop talking to each other for they become convinced that they will get nowhere. They think positions are fixed and will only be moved by deeds. This stage is the phase of "fait accomp/i"-that is, parties effectuate what they have been contending intellectually. In a conflict between teachers concerning different basic philosophies of education, each party starts teaching according to its own convictions. Through the pupils they confront each other with the consequences of their contentions. However, now one reality is confronting another. Deeds again give the parties a feeling of being autonomous. Thus, the attention of the parties moves from verbal to nonverbal means of communication. In cases of a discrepancy between verbal and nonverbal messages, the parties start to rely much more on nonverbal signals (Ekman and Friesen, 1969; Bugental, Kaswan, and Love, 1970; Mehrabian, 1972; Argyle, 1975) and on nonvocal expressions. Negative intentions and attitudes may be hidden and suppressed by the party's verbal and vocal expression but tend to "leak out" through their facial expressions, gestures, and bodily expressions. Orientation toward these nonverbal methods of expression means that people depend much more on their interpretations, guesses, and extrapolations. Out of tactical behavior they may draw conclusions on long-term intentions of the opponent. Thus, the parties start misperceiving and misinterpreting each other to a great extent. This fosters further aggravation and acceleration of the escalation. When groups engage in deeds, they develop strong internal group cohesion. Leaders become speakers of the parties, and an internal pressure emerges for conformity. Empathy disappears. The deeds of one party block the deeds of the other party and cause mutual frustration. During the first CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 127 main phase of escalation (stages one to three), the mixed motives ofthe parties change from predominantly cooperative to competitive. The parties consider it a matter of prestige to defend their own intellectual position, although they may see the merits of the other party's argument. Main Phase II The mutual relationships of the parties become the main source of tensions during the second main phase. Stereotyped images are built up and confirmed by "self-fulfilling prophecies." The psychological distance grows rapidly. Distrust, lack of respect, and overt hostility evolve and determine all actions. The parties cannot imagine solving the conflict together; the only means to solution lies in excluding the other party. Stage four: concern for reputation and coalition. At stage four the attitudes of the parties turn into "win/lose" motives. For this purpose the parties try to gather supporters who may also plead their case. Many campaigns are organized in order to gain sympathy and support. The parties try to find people to share their values and opinions rather than to form a potent power block to overwhelm the other side. Only at the end of main phase II will the parties engage in activities to form real alliances for aggressive purposes. Coalition forming at stage four aims at affinity. One wants other people to share one's self-image and one's image of the enemy. This is a symbiotic type of coalition (Richter, 1972) and an expression of a need to be understood and confirmed by others. The parties' self-image and the image of the enemy become very much polarized. Sherif (1962), Blake and Mouton (1961, 1962), White (1966) and others have shown that parties develop extremely stereotyped images of themselves that contrast completely with the images of the opposite side. The parties are not aware of their enormous distortions of perceptions but believe that their images are realistic ones. Unfortunately, these images cannot be rectified by new experiences, which may perhaps falsify the already existing perceptions (Kautsky, 1965). One sees what one wants to see: This is the field of prejudices. Most ofthe conflicts Blake (1961) was describing have reached stage four of escalation. The images of the parties have become fixed. Each side sees itself as the personification of all good capacities and attitudes and the other side as the representation of many weak and negative features. So far, how- 128 FRIEDRICH GLASL ever, all negative aspects are related only to intellectual and occupational knowledge, attitudes, and skills and do not yet imply any negative moral qualities. Moral disqualification is part of stage five. These self-images play an important part in the campaigns for coalition forming. Therefore, the parties watch all attempts of the opposite side whenever it approaches neutral people who have not yet chosen for one side. According to these images, the parties build up stable role patterns with the other party, which show many aspects of the "double-bind relationships" described by Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson (1968). Stage five: loss of face. The preceding stage shows that the parties confront each other with distorted self-stereotypes and heterostereotypes. Neither party feels that the other side has a correct view of its human qualities. A few uncontrolled incidents may be taken as evidence of the other side's fighting on immoral grounds. From that moment onward the fighting develops into a matter of "to be or not to be" in terms of one's social identity. The parties start attacking each other in order to prove that the enemy is lying or misleading. Such fighting results in a dramatic loss of face for one or for all parties involved, which means (Pondy, 1967) that the social and human integrity of a party is fundamentally shocked. Goffman (1955) has shown through many examples in numerous cultures of the world that such loss of dignity has dramatic meaning for most people. One's "face" is, according to Goffman, a "social loan," a kind of social credit given one. Once a party has lost face it may be deprived of all social rights in its social environment. The experience of loss of face is that of a fundamental disillusion, of demasque. Garfinkel (1974) analyzes the rituals of expulsion that follow loss of face. We can only compare these rituals with proscription in medieval times. In practice, we can observe that people at this stage of escalation become completely isolated. They describe their social position as "being dead. " As a result of this intensive experience, most people struggle for a complete rehabilitation of their dignity. The self-concept and the concept of the enemy have changed fundamentally. Each party perceives itself as "personification of the good as such," as an angel-like being, while the opposite party is perceived as "devil," as. mere representation of the bad (White, 1965; Daim, 1962; RochblaveSpenle, 1973, among others). The change in perception explains why, from stage five onward, the parties behave very rigidly and look upon their conflict as a matter of prime importance. Their basic values seem to be at stake and must be defended. Even issues of minor importance are now viewed in the light of examples of good and bad, and are related to matters of ideolo- CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 129 gies, philosophies, or religion. Thus, the conflict is considered to be a holy war. It is not enough to defend one's personal belief; it becomes a fight for the victory of the good and right way of thinking in general. One can imagine that the conflict now becomes absolute. Compromises as a way of solving differences become excluded because "one cannot compromise in matters of truth itself." Stage six: dominance of strategies of threat. After stage five, violence increases very much. The conflict process accelerates and causes intense feelings of stress. During all preceding stages the parties use tactics of threat sometimes, but at stage six the use of threats becomes predominant and determines everything that happens. Threat aims at changes in the other party's position by exerting pressure. Paradoxically, however, the effect of threat is, as Schelling (1957) and Deutsch (1968) emphasize, contrary to its aims. While threats try to urge the other side to refrain from further violence, as a matter of fact they are actually provoking more violence: A threat of one party is answered by a counterthreat of the other party. Milburn (1977) shows that the credibility of threats depends on the balanced relationships of four components: (1) the demands, (2) the promised punishments or sanctions, (3) the potential to carry out the promised sanctions, and (4) the expected damage the sanctions may cause to the other side. For these reasons a threatening party starts "overdemanding" and "overpunishing" to put more pressure on the other side. In order to increase the credibility of one's threat, one must-at least in a few instances-start to carry out what one promised to do to the other party. If one is not firm in carrying out a minor threat, one will not have credibility in regard to carrying out a major sanction. Thus, according to Deutsch (1968), threats do provoke or cause the very situations they had wanted to prevent: They increase defensiveness, which becomes an aggressive preventative action. In addition, for credibility's sake one has to demonstrate some acts of violence to emphasize one's commitment to more serious deeds. Threats lead to "overdesign" and "overreactions" (Senghaas, 1970) because the other side prepares itself to meet the "worst-of-all-possibilities." Rathjens (1969) and Proxmire (1970) show how this mechanism leads to an accumulation of violent acts within a short time. Now all parties adopt patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that are well known as "crisis decision-making patterns" and are described by Holsti, Brody, and North (1964), Paige (1969), Janis (1972), and many other scholars of international crises. 130 FRIEDRICH GLASL Main Phase III All confrontations between the parties become very tough at this stage. The other party no longer represents any kind of human dignity but is treated as material goods and no more. Destruction prevails, and any attempt to achieve something positive is blocked. How to hinder the other side becomes a goal in itself. At the end of phase III, the parties believe that their positions are completely irreconcilable and that no way out of the disaster exists. Therefore, they prefer to face total confrontation and destruction, even at the expense of their own existence. Due to the fact that professional conflict consultants in industry are not normally faced with escalation beyond stage six, we will only examine a few characteristics of the next three stages (more details will be found in Glasl, 1980). Stage seven: systematic destructive campaigns against the sanction potential oj the other party. The intention to cause damage to each other becomes predominant. It is no longer possible to achieve something positive. Thus, one is only concerned with the other party's damage being greater than the damage one suffers oneself. The target of one's attack is the sanction potential of the other side. By attacking or destroying it, the strategies of threat may become paralyzed. In industrial conflicts the parties try to block various means of control systems. Sometimes personnel officers are considered to be the "police force" of a firm and therefore become the direct objects of destructive actions. Emotionally, destruction provides a compensation for loss of power and influence. However, once the parties are engaged in the "tit-for-tat" game, the conflict can escalate easily. Stage eight: attacks against the power nerves oj the enemy. Having experienced the frustrations of stage seven, the parties concentrate on the essentially destructive effects of their attacks. They try to hurt the other side substantially, not just to prevent further threats. Kahn (1965) describes it as the power nerves being destroyed. For example, during a very serious strike the representatives of management tried to undermine the total credibility of union representatives so much that they could not be elected any more. "They will get nothing to win!" the management said. In turn, shop stewards attacked management by spreading rumors and scandals so that the shareholders had to recall the top manager for his "shocking and irresponsible behavior" in the past. This was followed by significant changes in management. CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 131 Constituencies' trust is the power base of both sides. Although a conflict may have started as friction with regard to some salary increase, it may end up with essential damages to a plant or a union. The parties prefer to go ahead and to risk more damage rather than to withdraw and "capitulate." Advancement of prestige becomes more important than an economic calculation of costs and benefits. The conflict has now reached a completely irrational stage. Stage nine: total destruction and suicide. In the final stage of escalation, the parties lose control of any limitations to violence. The conflict tends to become total and to end with the collapse of either side. Everything is leading to confrontation. As Kahn (1965) puts it with regard to thermonuclear warfare: "The parties press all buttons of the machinery of destruction at once!" Even the environment of the fighting parties will be drawn into the final battle and runs the risk of being damaged. The audience is not permitted to stay neutral. Suicide may even be perceived as favorable if one knows that the other side will be destroyed as well. This brief description of a few essential characteristics of each stage of escalation suggests what interventions third parties will have to take into consideration. It explains why some interventions may not be successful at stage five, for example, although they might be very effective at stage three or four. The correct diagnosis of the degree of escalation is highly relevant for selecting an appropriate course of action by a third party. BASIC CONFLICT-HANDLING STRATEGIES AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES In the first part of this paper, a few well-known strategies of third-party conflict handling were mentioned. Now we can relate the most prominent strategies to the stages of escalation. Figure 6.2 shows the main emphasis of these strategies. Some strategies overlap with others, depending on factual aspects related to the following questions: • • • Are there many persons involved at the highest stage visible, or is there only a nucleus group of main actors engaged in conflicts at, for example, stage five, while the other people in the department are only engaged at stage four or three? How rigid or how flexible are the parties? How much time will be available for treatment? 132 FRIEDRICH GLASL 2 I Stage of escalation 4 5 6 3 I I I I I I : I . ' : 1 1 1 1 I : 1~-_'i"'1_______' _ _.-,1 Moderalion i 1 : ! I I , I : I I , ! I I I~ I I I I • ~ I I I i l l : I 1 , I I I I I 1 -I 1 ' I I I Sociotherapeutic process consultation I i I i :--: i , I ----1---1 iMediation! I i__ : I I I I I 1 1 1 I I I , I : I I : 1 I I :: r I : : I I 1 1 __- I i i __! _ _.....: : I FIGURE 6.2. escalation I Pro~ess consul~ation 1 I ' 9 8 7 : Arbitratio~ I 1 ,___1,.--.........._;-.1__-1 I I I : Power intervention , I ,, Strategies for third-party interventions related to stages of Strategy of a Moderator For conflicts of low intensity, the approach of "moderation" will be appropriate. It consists of interventions that clarify misunderstandings and misperceptions and deal with other kinds of cognitive and semantic differences. Eiseman (1978) has developed many methods to deal with this kind of conflict, which help attempts to overcome a polarization in thinking and feeling. His methods can assist people in getting out of extreme and inflexible positions. In addition, a moderator could make use of many techniques of intervention developed by the German "metaplan-team" (Siemens Autorenteam, 1974), which aim at quickly identifying undercurrents and visualizing unexpressed feelings and intentions. Van Hoesel (1957) and Rother (1976) present many methods to "disarm" a debate in which unfair tactics may be used. Beckhard's (1969) well-known method of confrontation meetings is suitable for dealing with less intensive conflicts but will fail at stage three or four of escalation. The methods of "integrated decision making" developed by Filley (1975) are also useful in helping to solve problems. All these methods rely on a high degree of rationality of the parties and may easily be applied by the parties themselves. The moderator will soon become superfluous because his skills will be internalized by the parties themselves. CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 133 Strategies of Process Consultation The concept of process consultation and its methods have been explored and developed during the last ten years. Blake, Mouton, and Shepard (1964), Walton (1969), Glasl (1969, 1972), Prein (1979a, 1979b), Mastenbroek (1979), and others describe the use of process consultation in industry, while Burton (1969), Kelman (1972), Fisher (1972), Young (1972) and others report on its effects in international and intercommunal conflicts. The main aim of process consultation is to foster the parties' capacity to solve their own conflicts in such a way that they resolve the problems at the roots of the conflicts and cure the psychological mechanisms that have been at work during the conflict process. Most interventions deal with clarifications of misperceptions, clearly illustrated by the approaches of Blake, Shepard, and Mouton (1964) and Burton (1969). The parties are assisted and directed by the process consultant to describe their stereotyped perceptions of each other and to relate them to their factual behavior. Walton (1969) and Fisher (1972) emphasize working on attitudes as well. Harrison (1971) offers some practical methods for dealing with the parties' behavior by means of "role negotiations." Analyzing relations of the parties and changing them require many interventions. Process consultation goes much deeper than moderation is ever meant to go. It deals with changes on middle-term perspectives that will affect basic convictions, values, and motives of the parties. A process consultant must be prepared to guide clients-at least at the beginning and with regard to procedures and methods of conflict solving-in a more directed way than a moderator would do. Conflicts that have entered stage five (loss of face) cannot be cured effectively by these ordinary methods of process consultation only. They require intervention of a sociotherapeutic nature as well. Sociotherapeutic Process Consultation Conflicts at the fifth stage of escalation need special attention because of the deep wounds the parties have suffered at each other's hands. Interventions have to reach a very deep personal level to help people reestablish a new self-concept resulting from loss of face. Self-esteem and self-confidence have to be built up as preconditions for any further intervention. Sociotherapeutic process consultation requires much more time in consolidating the internal structure of the parties before direct intergroup encounters or confrontations can be arranged. 134 FRIEDRICH GLASL In the last five years of practice as consultants, my colleagues and I have had the opportunity to develop new approaches and methods for this type of third-party intervention. Our main inspiration stems from methods used in family therapy, especially those developed by Boszormenyi-Nagy and Framo (1965) and Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson (1968). In many respects the models elaborated by Richter (1967, 1972) have also been helpful because of their approaches to neurotic role relationships and role constellations in groups. These models proved to be applicable to organizations and not restricted to marriage and family situations. Another important source of inspiration has been the methods of psychosynthesis (Assagioli, 1971, 1973) and of Gestalt therapy (perls, 1975; Herman and Korenich, 1977), although these approaches have not yet been suitably adapted to conflicts within an organizational framework. However, they may open important fields of research and practice in the future. Strategy of Mediation Intervention by a mediator belongs to the classical third-party intervention in diplomacy (Von Hentig, 1965), industrial relations (Douglas, 1957), and intercommunal conflicts. When the parties of a conflict within an organization believe that no basis exists for a joint conflict resolution-as is the presumption in process consultation-then a mediator may be useful (Young, 1972). A mediator is essentially a negotiator (Prein, 1979c). He tries to negotiate between the parties and to help them build up trust with regard to the third party. This trust has to compensate for the total lack of trust that becomes predominant after stages five and six. A mediator as "gobetween" has to respect the parties' not being completely open toward him because they may fear that openness will be misused by the third party. As a negotiator, the mediator may be confronted with the same dilemmas the parties themselves are struggling with. He selects information, watches the tactical moves of the parties, and tries to fulfill those communicative functions the parties can no longer fulfill themselves in direct confrontations. On the other hand, all methods and means of pressure are available to the mediator to the same extent that they are available to the parties. As a rule, the results of a mediation process are less penetrating than the intervention of a process consultant would be. Very often nothing more can be achieved than a status quo arrangement as a basis for further coexistence. Later, perhaps, curative intervention may follow once the parties have established some control of the conflictive situation. CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 135 Strategy of Arbitration In order to transfer a matter to arbitration or any other kind of judicial intervention, the parties have to redefine their conflict in terms of a dissent on standards or a dissent on facts (Aubert, 1963). Thus, the original conflict has to be transformed into a "metaconflict," as Galtung (1972) calls it, and the decision of an arbitrator must provide such satisfaction as the solution of the basic conflict might offer. Once a conflict is handed over to an arbitrator, the parties become rather passive and reactive to the moves of the arbitrator. The effect of arbitration penetrates less deeply into the internal world of the parties and will have less preventative effects than the other approaches mentioned. On the other hand, arbitration offers a way out where the parties themselves have come to a complete deadlock. Therefore, arbitration proves to be very effective at the deeper levels of escalation, especially when tactics of self-commitment and threat have destroyed the basis for further cooperation. Power Intervention Mediators and arbitrators may use various degrees of power to have their proposals carried out. However, power intervention is not concerned with the acceptance of the superimposed solutions. If a supervisor intervenes in a conflict between his departments, he may determine the further actions, he may decide on rights and wrongs, and he may even punish the parties involved. The only requirement is his factual and/or formal power base. There are many different power interventions, ranging from so-called expert analysis, which is followed by a mere power intervention, to joining the conflict either on one side or as a third party to the conflict. Moreover, it may be that joining the conflict only results in escalating the conflict further instead of ending it. INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS CONFLICTS The six strategies of intervention presented here are all based on the assumption that the conflicts exist between parties who are supposed to coordinate and cooperate to achieve a common output. This is the case with people working together in a production process, teachers in school, and so forth. For conflicts of industrial relations, one must consider the basically 136 FRIEDRICH GLASL different relationships of the parties concerned. The different nature of the dependencies of shop stewards and management requires some modification of the strategies and role models described so far (see figure 6.3). Many writers characterize the typical nature of these relations as "noncorresponding relations" (La Tour et aI., 1976), as "distributive relations" (Herman, 1973), or as "political relations" or "negotiation framework" (pondy, 1967). We prefer to talk about "complementary dependencies" (Glasl, 1980) because this indicates the existence of a kind of "zero-sum-relationship" (Ephron, 1961): one party can only gain what the other side is losing. The parties are complementary to each other. Therefore, parties will never allow the other side to gain an insight into their real motives and objectives. They will not be open to any kind of influence on the role and social position that are determined by the positions of the parties in society. These restrictions limit the intervention of a process consultant or a sociotherapeutic process consultant. Chase (1951), Peters (1952, 1955), Margerison and Leary (1975) use the term conciliator in order to characterize a different type of third-party intervention that may seem a combination of mediation and process consultation. We describe "conciliation" as a kind of process consultation with regard to processes oj negotiation, not of cooperative problem solving. Negotiators know that they are dependent on each other but are concerned Stage of escalation 4 5 6 2 1 1 I I I 8 7 I I I I I I 9 I I I Moderator Chairman : : : : : : : : i : : : : I I I I : j----...-;.- ~-I-I----1 : Conciliato~: i: I I I~- _ _- : : I !Mediator:I : :: --I I : I I I I : : I I I : I : I I I ~~I_ _ _ _ ~ , I I : I : : : I ~ I I I I I I I i I I I I Arbitrator I I I : I I I I Power intervention I I FIGURE 6.3. Strategies for third-party interventions for industrial relations conflicts CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 137 with their own (complementary) interest in the first place. A conciliator, as described by Peters (1952, 1955), Douglas (1957), or Rehmus (1953) can provide help for parties in these situations. DISCUSSION The different stages of escalation and the strategies of third-party intervention can be presented only in rough outline (Glasl, 1980). Yet the outline will show that an evaluation of a specific strategy must consider the degree of escalation of a conflict, the type of conflict, and the nature of the relationship between the parties involved. During the course of a long-term strategy of conflict handling, a third party may start with a mediation approach. Once some results have been achieved, this role must be changed consciously into, for example, a process consultation approach and may perhaps end at the level of moderation. A model of phases of a conflict-handling process should distinguish different basic phases, each requiring an appropriate role. These models allow a third party to explain clearly to a client which concept he will adopt and what the implications of it are for the client and the third party. Clarity of the explanation increases the chances of successful intervention. A deeper understanding of the process of escalation and its stages provides help in determining the right course of action. REFERENCES Argyle, M. 1975. Bodily Communication. London: International University Press. Assagioli, R. 1971. Psychosynthesis. New York: Penguin. _ _ . 1973. The Act oj Will. New York: Penguin. Aubert, V. 1963. "Competition and Dissensus: Two Types of Conflict and of Conflict Resolution." Journal oj Conflict Resolution 7 :26-42. Beckhard, R. 1969. "The Confrontation Meeting." In W. Bennis, K. Benne, and R. Chin, eds., The Planning oj Change. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Blake, R., and J. S. Mouton. 1961. "Comprehension of Own and of Outgroup Positions under Intergroup Competition." Journal oj Conflict Resolution: 304-9. _ _ . 1962. "The Influence of Competitively Vested Interests on Judgments." Journal of Conflict Resolution 6: 149-53. Blake, R., H. A. Shepard, and J. S. Mouton. 1964. Managing Intergroup Conflict in Industry. Houston: Gulf. Boszormenyi-Nagy, J., and J. L. Framo. 1965. "Intensive Family Therapy." New York: Harper & Row. 138 FRIEDRICH GLASL Boulding, K. E. 1957. "Organization and Conflict." Journal oJ Conflict Resolution 1:122-34. Bugental, D. E., 1. W. Kaswan, and L. R. Love. 1970. "Perception of Contradictory Meanings Conveyed by Verbal and Nonverbal Channels." Journal oj Personality and Social Psychology 16:647-55. Burton, J. W. 1969. Conflict and Communication. London: Macmillan. Chase, S. 1951. Roads to Agreement. New York: Greenwood Press. Cofer, C. N., and M. H. Appley. 1964. Motivation: Theory and Research. New York: Wiley. Daim, W. 1962 "Das Bild des Feindes." Der Christ in der Welt: 124-32. Deutsch, K. 1968. "Threats and Deterrence as Mixed-Motive Games." The Analysis oj International Relations. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. Deutsch, M. 1973. The Resolution oj Conflict. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. Deutsch, M., and R. M. Krauss. 1962. "Studies of Interpersonal Bargaining." Journal oj Conflict Resolution 6:52-76. Diesig, P. 1961. "Bargaining Strategy and Union-Management Relationships." Journal oj Conflict Resolution 5: 369-78. Douglas, A. 1957. "The Peaceful Settlement of Industrial and Intergroup Disputes." Journal oj Conflict Resolution 1:69-81. Eiseman, J. W. 1978. "Reconciling 'Incompatible Positions.' " Journal ojApplied Behavioral Science 11:133-50. Ekman, P., and W. V. Friesen. 1969. "Nonverbal Leakage and Clues to Deception." Psychiatry 31:88-105. Ephron, L. R. 1961. "Group Conflict in Organizations: A Critical Appraisal of Recent Theories." Berkeley Journal oj Sociology 6:53-72. Filley, A. C., 1975. Interpersonal Conflict Resolution. Glenview, Ill.: Scott, Foresman. Fisher, R. J. 1972. "Third-Party Consultation: A Method for the Study and Resolution of Conflict." Journal oj Conflict Resolution 16:67-94. Frei, D. 1970. Kriegsverhutung und Friedenssicherung. Frauenfeld. Galtung, J. 1973. "Institutionalisierte Konfliktlosung.', In W. L. Buhl, ed., Strategie des Konfliktes. Munich. pp. 113-77. Garfinkel, H. 1974 "Bedingungen fUr den Erfolg von Degradierungszeremonien." Gruppendynamik (April). Gelner, C. 1967. Die Kunst des Verhandelns. Heidelberg. Glasl, F. 1969. "Techniken der Konfliktlosung." Der Christ in der Welt (September). ___. 1972. "Methods of Conflict-Solving." Seminar Papers oj NPI, Zeist! Johannesburg. _ _ . 1980. Konfliktmanagement: Diagnose und Behandlung von Konflikten in Organisationen. Bern. Goffman, E. 1955. "On Face-Work." Psychiatry 18:211-31. Guetzkow, H., and J. Gyr. 1954. "An Analysis of Conflict in Decision-Making Groups." Human Relations 7:367-81. CONFLICT ESCALATION AND ROLES OF THIRD PARTIES 139 Harrison, R. 1971. "Role Negotiation: A Tough Minded Approach to Team Development." In W. Burke and H. Hornstein, eds., The Social Technology of Organization Development. San Francisco: University Associates. Hentig, H. von. 1965. Der Friedensschluss. Munich. Herman, C. F. 1973. International Crisis: Insightsfrom Behavioral Research. New York: Free Press. Herman, S. M., and M. Korenich. 1977. Authentic Management: A Gestalt Orientation to Organizations and Their Development. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. Hoesel, A. F. G. van. 1957. Zindelijk denken. Bilthoven/Antwerpen. Holsti, O. R. 1970. "Individual Differences in 'Definition of the Situation.' " Journal of Conflict Resolution 14:303-10. Holsti, O. R., R. A. Brody, and R. C. North. 1964. "Measuring Effect and Action in International Reaction Models: Empirical Materials from the 1962 Cuban Crisis." Journal of Peace Research 7:170-89. Janis, I. L. 1972. Victims of Groupthink. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Kahn, H. 1965. On Escalation: Metaphors and Scenarios. New York. Kautsky, J. H. 1965. "Myth, Self-Fulfilling Prophecy, and Symbolic Reassurance in the East-West Conflict." Journal of Conflict Resolution 9:1-17. Kelman, H. C. 1972. "The Problem-Solving Workshop in Conflict Resolution." In R. L. Merritt, ed., Communication in International Politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. La Tour, S., et al. 1976. "Some Determinants of Preference for Models of Conflict Resolution." Journal of Conflict Resolution 20:319-56. March, J. G., and H. A. Simon. 1958. Organizations. New York: Wiley. Margerison, Ch., and M. Leary. 1975. Managing Industrial Conflicts: The Mediator's Role. Bradford, U.K. Mastenbroek, W. F. G. 1979. "Conflicthantering: een procesbenadering." M & 0, Tijdschrift voor organisatiekunde en sociaal beleid (Jan/Feb):69-89. Mehrabian, A. 1972. Nonverbal Communication. Chicago: Aldine. Milburn, Th. W. 1977. "The Nature of Threat." Journal of Social Issues 33:126-39. Newcomb, T. R. 1947. "Autistic Hostility and Social Reality." Human Relations 7:69-86. Paige, G. D. 1969. The Korean Decision. New York. Peris, F. 1975. Legacy from Fritz. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science & Behavior Books. Peters, E. 1952. Conciliation in Action. New London, Conn. ___ . 1955. Strategy and Tactics in Labor Negotiations. New London, Conn. Pondy, L. R. 1967. "Organizational Conflict: Concepts and Methods." Administrative Science Quarterly 72:296-320. Prein, H. C. M. 1979a. "RoUen van een derde partij bij conflicthantering.', M & 0, Tijdschrift voor organisatiekunde en sociaal beleid (Jan/Feb):I00-24. ___ .1979b. "De rol van procesbegeleider." M & 0, Tijdschrift voor organisatiekunde en sociaal beleid (Jan/Feb):125-34. ___ .1979c. "De rol van bemiddelaar." M & 0, Tijdschrift voor organisatiekunde en sociaal beleid (Jan/Feb):135-44. Proxmire, W. 1970. Report from Wasteland. New York. 140 FRIEDRICH GLASL Rapoport, A. 1972. "Kataklysmische und strategische Konfliktmodelle." In W. Buhl, ed., Strategie des Konfliktes. Munich. ___ . 1974. Conflict in Man-Made Environment. Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin. Rathjens, G. W. 1969. "The Dynamics of the Arms Race." Scientific American 15-25. Rehmus, Ch. M. 1953. "Mediation and Conciliation." Labor Law Journal 4:141-44. Richter, H. E. 1967. Eltern, Kind und Neurose. Reinbek bei Hamburg. _ _ . 1972. Patient Familie. Reinbek bei Hamburg. Rocheblave-Spenle, A. M. 1973. Psychologie des Konflikts. Freiburg. Rother, W. 1976. Die Kunst des Streitens. Munich. Schelling, Th. C. 1957. "Bargaining, Communication and Limited War." Journal of Conflict Resolution 7:19-36. Senghaas, D. 1970. "Bedrohungsvorstellungen und Drohstrategien in den internationalen Beziehungen, unter besonderer Berucksichtigung der Abschreckungspolitik." In Papiere des Kolloquiums "Bedrohvorstellungen als Faktor der internationalen Politik" der Arbeitsgemeinschaft far Friedens- und Konflikt/orschung. Munich. _ _ . 1971. Aggressivittit und kollektive Gewalt. Stuttgart. Sherif, M., ed. 1962. Intergroup Relations and Leadership. New York: Wiley. Siemens Autorenteam. 1974. Organisationsplanung. Munich. Thelen, H. 1954. Dynamics of Groups at Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Thierry, Hk. 1977. Organisatie van tegenstellingen. AssenlAmsterdam. Thomas, K. 1976. "Conflict and Conflict/Management." In M. D. Dunnette, ed., Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Chicago: Rand McNally. Walton, R. E. 1969. Interpersonal Peacemaking: Confrontations and Third-Party Consultations. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. Watzlawick, P., J. H. Beavin, and D. D. Jackson. 1968. Pragmatics of Human Communication. New York: Norton. White, R. K. 1965. "Images in the Context of International Conflict: Soviet Perceptions of the U.S. and the U.S.S.R." In H. C. Kelman, ed., International Behavior. New York: Irvington. ___ . 1966. "Misperception as a Cause of Two World Wars." Journal of Social Issues 22:1-19. Wright, Q. 1965. "The Escalation of International Conflicts." Journal of Conflict Resolution 9:434-42. Young, O. 1972. "Intermediaries: Additional Thoughts on Third Parties." Journal of Conflict Resolution 16:51-65.