Orlando Study Guide: Virginia Woolf, High School Literature

advertisement

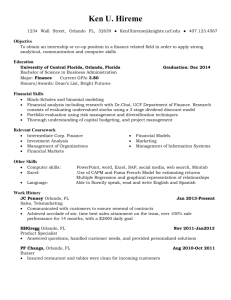

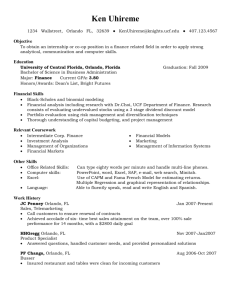

AULA ESCOLA EUROPEA ENGLISH LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT BATXILLERAT 2 STUDY GUIDE ORLANDO VIRGINIA WOOLF Cover Illustration: Courttheater 1 Virginia Woolf FROM THE OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY Woolf [NÉE Stephen], (Adeline) Virginia (1882–1941), writer and publisher, was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on 25 January 1882 at 22 Hyde Park Gate, London. She was the third child of Leslie Stephen (1832–1904), a London man of letters and founding editor of the DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, and his second wife, Julia Prinsep Duckworth, NÉE Jackson (1846– 1895). It was decided at an early age that Virginia was to be a writer. Writing absorbed her, she said, ‘ever since I was a little creature, scribbling a story in the manner of Hawthorne on the green plush sofa in the drawing room at St. Ives [the family summer home] while the grownups dined’ (V. Woolf, Diary, 19 Dec 1938). Virginia's bookishness drew her closer to her father than his other children were. Her mother caught her, at nine, twisting a lock of her hair as she read, in imitation of Leslie Stephen. Virginia‘s mother died unexpectedly, at forty-nine, on 5 May 1895. Later, Virginia pictured herself as she was at that time: an ‘emergent creature struck by successive blows as she sat with wings still creased on the broken chrysalis’. Leslie Stephen shaped Virginia's tastes, especially for biography. She picked up his reverential glow balanced by humour. He taught her to pit observed truth against established paradigms, and that if writing is to last it must have, for its backbone, some fierce attachment to an idea. But his deepest influence on his daughter's writing may lie in his unorthodox tramps. Virginia, too, was a walker. As though she were tracking a metaphor for her future work, she followed a natural path which ignored artificial boundaries. After her father's death in 1904 Virginia—together with siblings Vanessa, Thoby, and Adrian—left the solid red brick of Kensington for the superb fadedness of Bloomsbury. At home Virginia Stephen played up to the family's caricature of her as mad genius and helpless, scatty dependant of her sister. Yet she was professional and direct as a teacher from 1905 to 1907 at Morley College, a night school for workers in south London. As a writer, too, Virginia Stephen showed herself self-disciplined, professional, prolific, and courageous. She examined the hidden moments and obscure formative experiences in a life, rather than its more public actions. In Gordon Square the two Stephen sisters brought together a group of innovative men whom Thoby had known in Cambridge: Leonard Woolf (1880–1969), a stubborn, passionate man, alert to the ills of society and with the practical sense to combat them; the biographer Lytton Strachey; the art critic Clive Bell; the artists Roger Fry and Duncan Grant; the novelist E. M. Forster; and the economist John Maynard Keynes. The shock of Thoby's death in 1906 sealed his sisters' ties to his friends. Vanessa married Clive Bell in 1907, and the Stephens' Thursday evenings continued at 29 Fitzroy Square, where Virginia and Adrian set up a separate home. This proved the beginning of the Bloomsbury group. Bloomsbury abjured the chattiness of society for speculative silence; granted agency to women; welcomed sexual freedom and homosexuality; and generally ridiculed the social, religious, and moral orthodoxies of the Victorians. Virginia, at thirty, married Leonard Woolf on 10 August 1912 in St Pancras town hall. The adjustment to marriage, as well as fears for the publication of THE VOYAGE OUT, were the background to Virginia Woolf's breakdowns in 1913 and 1915. In 1915 Miss Thomas, director of Burley, announced that 2 Virginia's mind was ‘played out’ and persuaded her family that her character had permanently deteriorated. But the doctors and nurses who believed there could be no full recovery were wrong. By November 1915 she was ‘sane’. The twenty dark years were over, and the fertile stretch of her life began. From 1915 until 1924 the Woolfs lived quietly at Hogarth House, Richmond. There, in 1917, they set up the Hogarth Press, at first as a hobby and with a view to publishing their own work. Soon, though, the Hogarth Press became a publishing phenomenon, putting out some of the most advanced writing of the day, including works by T. S. Eliot, Katherine Mansfield, E. M. Forster, Maynard Keynes, Gorki, Freud, Robert Graves, Edith Sitwell, and of course the Woolfs themselves. At the time the press was established Virginia Woolf was writing her second novel, NIGHT AND DAY. From 1919 Virginia Woolf shaped the modern novel. She rejected the narrative coherence of Victorian fiction in favour of ‘an ordinary mind on an ordinary day’, often several minds. Her aim was to find in the ‘moment of being‘ a climactic inward event, parallel to what her friend T. S. Eliot termed ‘unattended moments’ and what James Joyce termed ‘epiphany’. Woolf and Eliot wished to cut through the voluminousness of nineteenth-century writing in order to identify ‘the moment of importance’. Both wished to cross the frontiers of consciousness where words fail. The Victorians had trusted language to say just what they meant; the moderns found this impossible, and therefore communicated through symbols—the lighthouse or the waves—which require a reciprocal effort on the part of the reader. Virginia Woolf therefore gave fiction the depth of poetry. Virginia Woolf entered the political arena with A ROOM OF ONE'S OWN (1929). The aim was to establish a woman's tradition, recognizable through its distinct problems: the age-old confinement of women to the domestic sphere, the pressures of conformity to patriarchal ideas, and worst, the denial of income and privacy (‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write’). Virginia Woolf wanted to retrieve rather than discard the traditions of womanhood. It suggested that women excluded from historical record were the true makers of England as they passed their unnoticed code of preservation from mother to daughter, cultivating domestic order and the arts of peace, as opposed to militarized thugs who repeatedly destroyed it. Where the ‘woman question’ in the nineteenth century was concerned largely with issues of the vote and education, Virginia Woolf became the leading spokeswoman for the dominant issue of the twentieth century: professional advance. Her support for the advancement of women co-existed with her readiness to love women. It was flirtatious rather than physical, and she remained evasive and ambivalent about her sexual identity, but she adored, romanced, mythologized, and wished to be petted by women, in particular the writer and gardener Vita Sackville-West, where romance, from December 1925, was bound up with the amusement Virginia Woolf found in the aristocracy. According to Vita, they made love only twice, despite many opportunities. ORLANDO: A BIOGRAPHY (1928) celebrates Vita as a man-woman, switching gender to endorse the androgynous creative mind through the ages. 3 Vita Sackville-West FROM THE OXFORD DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY West, Victoria Mary [Vita] Sackville- (1892–1962), writer and gardener, was born on 9 March 1892 at Knole near Sevenoaks, Kent, the only child of Lionel Edward SackvilleWest (1867–1928), and his wife and first cousin, Victoria Josefa Dolores Catalina Sackville-West (1862–1936), society hostess, the illegitimate daughter of Sir Lionel Sackville Sackville-West, second Baron Sackville (1827– 1908), and the Spanish dancer Josefa de la Oliva (NÉE Durán y Ortega, known as Pepita). Her father succeeded her grandfather as third Baron Sackville in 1908. She was known throughout her life as Vita. Her upbringing, both privileged and solitary, was shaped above all by the romantic atmosphere and associations of Knole, the sprawling Tudor palace set in a spacious park in Kent, where she spent her childhood. Her literary taste and temperament were created substantially by this aristocratic and historical backcloth and intensified both by the colourful and eccentric personality of her mother and by the gradual realization, with which she never entirely came to terms, that as a woman she could never inherit the Knole estate. Until she was thirteen she was educated by governesses at home before moving to Miss Woolff's day school in London, but her voracious reading in literature and history made her essentially an autodidact. Sackville-West was also exposed to French culture from an early age through her mother's friendship with Sir John Murray Scott, ultimate residuary legatee of the art collector Sir Richard Wallace and owner of the Château de Bagatelle in Paris. Before the First World War she also enjoyed the opportunity to travel to Italy, Russia, Poland, Austria, and Spain. Throughout her life these cosmopolitan early years (which left the residue of fluency in Italian and French) were juxtaposed, and not without tension, with a deep sense of rootedness within the Kent countryside. She began to write at an early age and completed eight historical novels, five plays, and a number of poems before she was eighteen. She privately published a verse drama about the poet Thomas Chatterton in 1909. However, continual shadows played across her youth in both direct and indirect forms. Most publicly there were two lawsuits that threatened the security and reputation of her family: in the first her mother's relatives tried to prevent her father's inheritance of Knole, and in the second, where Vita was one of the major witnesses, the relatives of Sir John Murray Scott tried to overturn his large bequest to Lady Sackville on grounds of undue influence. Both were successfully overcome, but they took their toll on her parents' marriage. These events, combined with her mother's increasingly manipulative and emotionally quixotic behaviour, made the outwardly dominant and self-confident Sackville-West more diffident and uncertain. On 1 October 1913, despite conducting love affairs with women, Sackville-West married Harold George Nicolson (1886–1968), son of Sir Arthur Nicolson (later Lord Carnock), at Knole. Sackville-West retained her maiden name. Nicolson was at this stage in his career a junior diplomat, and they began their married life in Constantinople, where he was currently posted. They returned to Britain in 1914 and their first son, Lionel Benedict Nicolson, was born in August that year. They lived both in London and at Long Barn, a house near Knole, which served as their country home between 1915 and 1930, where Vita wrote most of her early books and developed her first garden. A second son was stillborn in 1915, and their last child, Nigel Nicolson, was born in London in 1917. These years were crucial in three respects—for the emergence across a range of genres of her professional literary persona; for the full exploration of her sexual and emotional identity (what she called her dual nature); and perhaps above all for the maturation of an unconventional but harmonious marriage. Sackville-West, who signed all her books V. Sackville-West, published POEMS OF EAST AND WEST in 1917, a collection of lyric poems composed while she was in Constantinople. In HERITAGE (1919), 4 her first novel, she explored her own history through metaphors of genetic determinism, and in THE HEIR (1922) she vented her feelings about Knole. KNOLE AND THE SACKVILLES (1922), a historical work, found a large audience which continued once public access to stately homes began to increase. In the years immediately after the First World War Sackville-West became committed to a stormy and nearly self-destructive love affair with her school friend Violet Trefusis (1894–1972), daughter of Mrs Alice Keppel, mistress of King Edward VII. The lovers travelled around Europe with Sackville-West occasionally cross-dressed as a fictive persona, Julian. They collaborated on a novel, CHALLENGE (1923), that was published in America under Sackville-West's name but suppressed in Britain. It is dedicated to Violet and is about their relationship. Sackville-West very nearly left her husband altogether. However, this crisis in fact proved eventually to be the catalyst for Nicolson and SackvilleWest to restructure their marriage satisfactorily so that they could both pursue a series of relationships through which they could fulfil their essentially homosexual identity while retaining a secure basis of companionship and affection. Sackville-West's other lovers included the journalist Evelyn Irons and Hilda Matheson, head of the BBC talks department, and she was also very close to Virginia Woolf, whom she met in December 1922. Sackville-West's SEDUCERS IN ECUADOR (1924) was written for Woolf. Woolf returned the favour with her historical-fantasy novel ORLANDO (1928), a public love letter and tribute to Sackville-West. The novel sums up with unique subtlety and perception Vita's own multifaceted and sometimes discordant personality and her androgynous sexual appeal, historical imagination, and love of Knole. Knole House Knole is an English country house in the town of Sevenoaks in west Kent, surrounded by a 1,000- acre (4.0 km2) deer park. One of England's largest houses, it is reputed to be a calendar house, having 365 rooms, 52 staircases, 12 entrances and 7 courtyards. It is remarkable in England for the degree to which its early 17th-century appearance is preserved, particularly in the case of the state rooms: the exteriors and interiors of many houses of this period, such as Clandon Park in Surrey, were dramatically altered later on. The surrounding deer park is also a remarkable survivor, having changed little over the past 400 years except for the loss of over 70% of its trees in the Great Storm of 1987. The house was built by Thomas Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury, between 1456 and 1486, on the site of an earlier house belonging to James Fiennes, the Lord Say and Sele who was executed after the victory of Jack Cade's rebels at the Battle of Solefields. On Bourchier's death, the house was bequeathed to the See of Canterbury — Sir Thomas More appeared in revels there at the court of John Morton — and in subsequent years it continued to be enlarged, with the addition of a new large courtyard, now known as Green Court, and a new entrance tower. In 1538 the house was taken from Archbishop Thomas Cranmer by King Henry VIII along with Otford Palace. In 1566, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, it came into the possession of her cousin Thomas Sackville whose descendants the Earls and Dukes of Dorset and Barons Sackville have lived there since 1603 (the intervening years saw the house let to the Lennard family). Most notably, these include writer Vita Sackville-West (her Knole and the Sackvilles, published 1922, is regarded as a classic in the literature of English country houses); her friend and lover Virginia Woolf wrote the novel Orlando drawing on the history of the house and Sackville-West's ancestors. The then laws of primogeniture prevented Sackville-West herself from inheriting Knole upon the death of her father Lionel (1867-1930), the 3rd Lord Sackville, and the estate and title passed to her uncle Charles (18701962). 5 6 Terms and Themes Terms Themes Genre Gender Biography Identity Modernism Life and Death Magical Realism Memory and Past Biographer Society and Class Narrator Point of View Literature and Writing Motif Time Setting Love Tone Marriage Symbol Nature Imagery Fame Allegory Language Protagonist Nature vs. Art Antagonist History Foil Social Behaviour Writing Style Social Conformity Stream of Consciousness Morality The Self 7 Outline of Monarchs and English Writers 8 Chapter 1 Part 1 1. Who is Orlando? Give a detailed description. Nobleman, young, handsome, likes writing 16 year-old boy 2. Which two specific things are described in the house? Oak tree and the big noble house 3. How does the narrator define the role of the biographer? How is this role contradicted? Give examples. A biographer should only narrate facts, and not emotions or thoughts of the person that is writing about. In the book, the biographic role of the narrator contradicts this. 4. Describe the Elizabethan Age. How does it compare to that of the narrator’s? It was a great nation, wherre arts and culture were developed and appreciated 5. What is said about nature and literature? They don't get along 6. What’s the significance of the oak tree? Stabilitym to be rooted and part of something 7. Describe the relationship between the Queen and Orlando. How do both parties benefit from such a relationship? Orlando has privileges, and the Queen feels younger when being next to Orlando Part 2 1. Describe the Great Frost. What happened to the young country woman at Norwich? to the wayfarers? What did it mean for the people in the big city? Very cold period, during the late 17th century 2. Describe the meeting between Orlando and the Russian Princess. What do they have in common? How do they differ? They both could be men or women at the same time. He falls in love with her before knowing her sex. They are the only ones that speak french. 3. Who is the Russian Princess named after? What does this foreshadow? Fox ==> it means that she is not honest, he also describes her as a melon or an emerald 9 4. Why is Orlando frustrated by the English language? What does he fail to capture? He can't explain to Sasha what he wants. He can't find words to describe her. 5. What caused a scandal at Court? The fact that Orlando flirted with Sasha while he was engaged with Euphrosine. 6. What happens aboard Sasha’s ship? What does Sasha say? Do you believe her? Does Orlando? 7. Analyse the role of sun/light and moon/darkness in Sasha and Orlando’s romance. Chapter 2 Part 1 1. According to our biographer, what is the first duty of a biographer? Why is Orlando’s life difficult to chronicle? 2. What is Orlando’s current life situation? 3. What happened on Saturday June 18th? 4. What does the biographer take the time to reflect on? 5. Where does Orlando indulge in feelings of death and decay? What conclusions does he arrive at? 6. Why does he break down sobbing in front of a painting? 7. What two diseases does Orlando suffer from? Why are they dangerous? 10 8. Why is the pause before Orlando begins to write said to be of extreme significance in his history? Orlando paused once before, what happened then? Can you predict what will happen now? Who is now dancing around his heart? Like Thomas Brown, what does Orlando wish to achieve? 9. What is said about memory? What analogy is used to describe it? 10. Why was Orlando happy for the first time since the great flood? 11. Who is Mr. Nicholas Greene? What’s he like? Why is Orlando disappointed when he meets him? 12. What does Nick Greene reveal about poetry and the poets of his age? 13. Why does Nick Greene leave? 14. What’s Nick Greene’s opinion on “The Death of Hercules”? 15. Why does Orlando say he’s done with men? Part 2 1. What does Orlando begin to frequent? What does he do there? 2. What is said about “time” and “memory”? 11 3. Explain the metaphor of the lump of glass at the bottom of the sea. 4. What is said about nature and literature? 5. What oath does Orlando swear? How does it help him move on? 6. What new conclusions does he arrive at regarding fame? 7. What new project does he begin? What does he find is still missing when he is finished? 8. When Orlando begins to revise his poem “The Oak Tree”. How has his writing changed? What is this a sign of? 9. Who is the Archduchess Harriet? Why does he compare her to a hare? How is she unconventional? 10. Is Orlando in love again? 11. What does Orlando decide to do? 12 Chapter 3 1. What does the lack of reliable information during this period of Orlando’s life mean for the biographer? 2. How does Constantinople compare to England? Orlando finds Turkey quite different from the manor houses he has known in England, but he enjoys Constantinople's wild, exotic quality. Though he has a magnetic quality that draws people to him, Orlando finds no close friends in Constantinople. 3. What does the job of Ambassador entail for Orlando? Is he happy? Orlando carries out his ambassadorial duties so well that King Charles gives him a dukedom, raising him to the highest office of the peerage. plus 4. Why is Orlando a legend? Very popular above both genders 5. What happened when Orlando put on his new crown of Duke? Moment when he decided that he was no longer a man, going into transition of 7 days 6. Who is Rosina Pepita? A known gipsy dancer, as a Romani dancer, she is well below Orlando’s social status as a Duke. Orlando's servants find him alone in his room, asleep, they wake him up and find a marriage license to Rosina Pepita. 7. What roles do Purity, Chastity and Modesty play? How do they feel about Truth? As Orlando lies in the trance, three figures enter: Lady of Purity, Lady of Chastity, and Lady of Modesty. They dance around Orlando's body and try to claim him, but trumpets sound. They decide that this is a place for Truth and not for them, so they leave. The trumpeters blast one note at Orlando, "the Truth" and he awakes. He stands upright, naked, and is now a woman. 8. What happens to Orlando? How does Orlando react? Orlando is now a beautiful woman, with the strength of a man and a the grace of a woman. Orlando is not at all upset by this change. stuck a pair of pistols in her belt her pearls => only way to pay people, to show her status 9. Where does Orlando go? With who? What does she take with her? Orlando’s life with the Romani people reflects her grandmother’s life, who was some sort of peasant, and Orlando easily adapts to their way of life. Orlando’s marriage to Rosina and her previous contact with the Romani people suggests that there is much the reader doesn’t know about Orlando’s life, which again underscores the problem with biographies as Woolf see it. 10. Describe Orlando’s new life. How do Orlando’s and the gipsy’s view on nature belonging differ? On ancestry? On property? Orlando finds truth in nature and worships it like a god or religion, but the Romani people don’t share this particular view of truth. 11. What does Orlando miss most? His house, England and the oak tree ==> poetry (only poem he takes with him), plus, oak tree represents stability so he misses stability 12. How and why did Orlando decide to go home to England? Orlando’s aristocratic heritage is part of her identity, like writing and poetry, and she therefore can’t abandon it. 13 METAPHORS Chapter 4 Part 1 1. What benefits and disadvantages of both sexes does Orlando think about on her way home to England on the Enamoured Lady? 2. What are some things that, as a woman, Orlando is now enjoying? 3. As a man, how did Orlando expect women to be? What does she think about this now that she is a woman? 4. What things must Orlando give up now that she is a woman? What must she now embrace? 5. Why does she consider returning to Turkey to live with the gipsy’s again? 6. Does feminine compliance to male domination comes with certain rewards? 7. What does Orlando think about Sasha now? 8. How does Orlando feel when arriving to England? 9. How has London changed while she has been away? 10. What legal problems does Orlando encounter upon her arrival? 11. How is Orlando received in her country home? Is there any confusion because of her sex change? 14 12. What are Orlando’s thoughts on religion? 13. What is revealed about the Archduchess Harriet? 14. “In short, they acted the parts of man and woman for ten minutes with great vigour and then fell into natural discourse.” Comment / explain. 15. Why is the engagement broken? 16. What’s Orlando looking for? 17. According to the text, what effect do clothes have on us? Do you agree? Orlando now feels like a woman. Why? Did she feel like a woman amongst the gipsies? Why / why not? Orlando takes to switching genders, and dons male or female clothes depending upon which is more appropriate for the moment. She finds that living in two genders is doubly fulfilling. She uses her male persona to eavesdrop on interesting conversations in coffee houses, like those of Dr. Johnson and Mr. Boswell. 18. What is said about the difference between the sexes? Part 2 1. How did the Archduke rescue Orlando? 2. What is said about society? Explain the comparison with dogs. 3. Having denounced society, why does Orlando visit Lady R? 4. Describe the gathering at Lady R’s. 15 5. What is the role of light and darkness in Orlando and Mr Pope’s drive home? 6. What does Orlando learn about Pope, Addison, and Swift? 7. What happened while Orlando was pouring tea for Pope? 8. Where does Orlando go after meditating under the willow tree? How is she dressed? 9. According to the text, what do women desire? 10. Why was it difficult for the biographer to chronicle Orlando’s life after this? 11. What is the black cloud that covers London? 16 Chapter 5 1. How has the black cloud changed England? What is the biographer implying? What happened to the light? What does the damp represent? What happened to the sexes? How has the life of the average woman changed? What about literature? What vision does Orlando have? How might you interpret this? 2. How does the Spirit of the Age affect Orlando? 3. While reading “The Oak Tree”, what conclusions does Orlando arrive at? 4. What fantastic thing happens as she attempts to write? 5. Describe how Orlando came to meet Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, Esquire. 6. How are Orlando’s lawsuits resolved? 7. Why do Orlando and Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, Esquire question each other’s sex? 8. Why does Orlando call Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, Esquire by so many names? What do they mean? Who are they a reflection of? 9. What happened at the end of the chapter? 10. Compare Sasha to Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, Esquire. How different are the relationships Orlando had with both? 11. Discuss Shell and Orlando’s relationship with regard to Nature and their nature (pun intended). 17 Chapter 6 Part 1 1. How does the conflict between Orlando and the Spirit of the Age resolve itself? 2. What are Orlando’s concerns about her marriage? 3. What problem does the biographer face now? 4. In what tone does the biographer talk about women writers? What does she say? What does she imply? 5. What does the biographer say about life? 6. What has Orlando finished? What does it want? 7. In Orlando’s visit to London, what changes does she perceive? Who does she run into? How has he changed? How has he remained the same? 8. Why is Orlando disappointed as a result of this meeting? 9. What does this critic think of “The Oak Tree”? 10. What is Rattigan Glumphoboo? Something in the language of Shel and Orlando 11. What question does she ponder ten minutes after reading Green’s article? 18 12. What does Orlando see in the Serpentine? What does she conclude as a consequence? 13. Back in her home in London, what conclusions does she arrive at about Victorian literature? 14. What is stream of consciousness? Lots of information coming without any filters 15. What happens at the end of the section? She has a baby "the Kingfisher" Part 2 It is also Mrs Banting who voices the culmination of any woman’s desire, according to Freud, i.e., the birth of a son, possessor of the phallus, which she can never hope to embody. But the son in Orlando is reduced to a silent, almost abstract concept of no importance at all. Chief protagonist in the birth scene is the kingfisher, whose coming, like the coming of the baby, demands patience and composure. The desire for a son is displaced in the text into the expectation of the kingfisher, symbol of serenity and calmness after the storm. 1. As Orlando looks out the window, she contemplates how England changes again. What changes does she perceive? What year is it? 2. What does Orlando reflect on at the department store? 3. Who does she spot while shopping for sheets? What does she cry out? 4. Orlando is having trouble with time. Explain. 5. According to the biographer, who are the successful people in life? 6. What does the biographer say about the different selves? 7. What new limitations on the genre of biography does the biographer point out? 19 8. What continually brings Orlando back to the present while in reveries? Is this a running motif during the novel? Have we seen it before? 9. Why doesn’t Orlando bury her poem at the foot of the oak tree? 10. At the end when she looks into the darkness what happens? Why does she cry out “Ecstasy!”? What is the wild goose? 11. What is emphasized about time in this chapter / book? 20