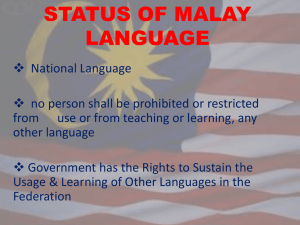

MALAYSIA History of Literature Malaysian literature is typically written in any of the country’s four main languages: Malay, English, Chinese, and Tamil. - Tamil is an official language of the sovereign nations of Sri Lanka and Singapore, and spoken primarily in India. It portrays various aspects of Malaysian life. Early Malay literature was primarily influenced by Indian epics such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, which later included other traditions that now form the Malay literary heritage style of writing, such as the Hikayat Mara Karma, Hikayat Panca Tanderan, and Hikayat Gul Bakawali, which were delivered orally through generations. Malay literature effectively begins with the coming of Islām in the late 15th century; no literary works dating from the Hindu period (4th to late 15th centuries) have survived. Malay literature can be divided into two types: that written in classical Malay, the written language of Malayspeaking Muslim communities scattered along all of Southeast Asia's coasts from the 15th century but focused primarily on the straits of Malacca; and that written in modern Malaysian Malay, which began to replace classical Malay in Malaya around 1920. By the 19th century, written literature occurred. - Oral literature on the Malay peninsula had been replaced by written literature by the 19th century. The adoption of Islam to the Peninsula in the 15th century, as well as the development of the Jawi script, were credited with this. This tradition was influenced by both prior oral traditions and Middle Eastern Islamic literature. Works during this time ranged from theological literature and legal digests, to romances, moral anecdotes, popular tales of Islamic prophets and even animal tales, which were written in a number of styles ranging from religious to the Hikayat form. Traditional Malay poetry was used for entertainment and the recording of history and laws. Religious Groups of Malaysia Malaysia a meeting ground of cultures and religions for thousands of years. Because of this, nearly all the major world religions have a longstanding notable presence in Malaysia today. For instance, 19.8% identify as Buddhist, 9.2% identify as Hindu, and 6.3% identify with traditional Chinese religions (such as Confucianism and Taoism). Religious Pluralism and the State The religious pluralism of Malaysia means that religious identity is often an important aspect of an individual, especially due to the association between ethnic and religious identity. Islam in Malaysia • Islam was first introduced to the region of present-day Malaysia by Arab and Indian traders and merchants from the 10th century through to the 15th century. • Today, nearly two-thirds of Malaysia’s population (61.3%) identify as Muslim. Most are Sunni and follow the Shafi’i school of thought and law. Buddhism in Malaysia • Both Buddhism and Hinduism were introduced to Malaysia over two millennia ago by Indian traders. • Buddhism also spread to the northern part of the Malay Peninsula from Thailand. For many centuries after, both religions heavily influenced Malaysian society, arts, culture and governance. • Immigrants from China and Sri Lanka during British colonial rule brought a resurgence of Buddhism back to Malaysia in the late 19th through to the 20th century. Today, Buddhism is the second most identified religion (19.8%). Christianity in Malaysia • Christianity was first introduced to the Malay Archipelago by Arab, Persian and Turkish Christian traders from the 7th century. • Catholicism was introduced by Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century, while Dutch colonists introduced Protestantism in the 17th century. • Protestant missions from various denominations flourished during British colonial rule from the 19th century. The 20th century saw the introduction of non-denominational and evangelical churches. Malaysian Folklore Malaysian folk tales include a vast variety of forms such as myths, legends, fables, etc. The main influences on Malaysian folk tales have been Indian, Javanese and middle eastern folk tales. Many Indian epics have been translated into Malay since ancient time including the Sanskrit epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata, which are the basis of the Malaysian art of Wayang Kulit. Besides, Indian epics, the Javanese epic of Panji has also influenced Malay literature and plays a major part in enriching Malaysian folk tales. Malaysian folk tales are usually centred around romance between princes and princesses, kings and queens, or heroes and their damsels. Until today, numerous royal courts exist in Malaysia and supplied the basis of many folk stories. For example, folk tales like Puteri Lindungan Bulan and Raja Bersiong have always been associated with the Sultanate of Kedah, and the story of Puteri Limau Purut has been associated with the Sultanate of Perak. Due to the nature of migration in the region, some of the popular Malaysian folk tales may also arrived from other part of Malay archipelago. Crocodile and Mouse Deer Sang Kancil was a clever mouse deer. Whenever he was in a bad situation, he always played a clever trick to escape. In this story, Sang Kancil outwitted Sang Buaya, a big, bad crocodile, who wanted to eat him. There were many trees where Sang Kancil’s lived along the river, so he never had trouble finding food. There were always lots of leaves. He spent his time running and jumping and looking into the river. Sang Buaya, the big bad crocodile, lived in the river with other crocodiles. They were always waiting to catch Sang Kancil for dinner. One day when Sang Buaya was walking along the river, he saw some delicious fruit on the trees on the other side the river. Sang Kancil wanted to taste the tasty-looking fruit because he was a little tired of eating leaves. He tried to think of a way to cross the river, but he had to be careful. He didn’t want to be caught and eaten by Sang Buaya. He needed to trick Sang Buaya. Sang Kancil suddenly had an idea He called out to the crocodile, “Sang Buaya! Sang Buaya!” Sang Buaya slowly came out of the water and asked Sang Kancil why he was shouting his name. He asked Sang Kancil, “Aren’t you afraid I will eat you?” Then he opened his big mouth very wide to scare Sang Kancil. Sang Kancil said, “Of course, I am afraid of you, but the king wants me to do something. He is having a big feast with lots of food, and he is inviting everyone, including you and all the other crocodiles. But first, I have to count all of you. He needs to know how many of you will come. Please line up across the river, so I can walk across your heads and count all of you.” Sang Buaya was excited and left to tell the other crocodiles about the feast with all the good food. Soon, they came and made a line across the river. Sang Kancil said, “Promise not to eat me because I can’t report to the king how many of you are coming. They promised not to eat him. Sang Kancil stepped on Sang Buaya’s head and counted one. Then he stepped on the next one and said, “Two.” He stepped on each crocodile, counting each one, and finally reached the other side of the river. Then he said to Sang Buaya, ”Thank you for helping me to cross the river to my new home.” Sang Buaya was shocked and angry. He shouted at Sang Kancil, “You tricked us! There is no feast, is there?” All of the crocodiles looked at Sang Buaya angrily. They were angry because he let Sang Kancil trick all of them. Sang Kancil loved his new home on the other side of the river because he had a lot of tasty food to eat. Poor Sang Buaya was not so lucky. After that, none of the other crocodiles ever talked to him again. Kancil (kahn-chill) = Mouse-deer; Jambu air (jahm-boo ah-yer) = Water Apple; Sang Buaya = the word “buaya” is Malay for crocodile. “Sang”, stand alone, has no real meaning, and is used in reference to an animal. Moral Lesson: The moral values that we can get from this story are we have to be brave to survive in this world because if not, the world will leave us behind. Other than that, we have to find a solution to any problem that we have because every problem in this world will have a solution. But not to trick because being tricky can hurt others. It’s not good. Like in the story the other crocodiles get mad to Sang Buaya because he let Sang Kancil to trick them and no one ever talk to him. Even Sang Kancil don`t hurt Sang Buaya physically he hurt him emotionally and mentally. Malay Authors and their Famous Works For centuries authors have been among the world's most important people, helping chronicle history and keep us entertained with one of the earliest forms of storytelling. Whether they're known for fiction, non-fiction, poetry or even technical writing, the famous Malaysian authors have kept that tradition alive by writing renowned works that have been praised around the world. Tash Aw Tash Aw, whose full name is Aw Ta-Shi (Chinese: 歐大旭; pinyin: Ōu Dàxù; born 4.10.1971) is a Malaysian writer living in London. Like many Malaysians, he had a multilingual upbringing, speaking Chinese and Cantonese at home, and Malay and English at school. His first novel, The Harmony Silk Factory, was published in 2005. It was longlisted for the 2005 Man Booker Prize and won the 2005 Whitbread Book Awards First Novel Award as well as the 2005 Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best First Novel (Asia Pacific region). Born in Taiwan to Malaysian parents, Tash Aw grew up in Kuala Lumpur before moving to England in his teens. He studied law at the University of Cambridge and University of Warwick, then moved to London to write. After graduating he worked at a number of jobs, including as a lawyer for four years whilst writing his debut novel, which he completed during the creative writing course at the University of East Anglia. Based on royalties as well as prizes, Aw is the most successful Malaysian writer of recent years. Following the announcement of the Booker longlist, the Whitbread Award and his Commonwealth Writers' Prize, he became a celebrity in Malaysia and Singapore, and is now one of the most respected literary figures in Southeast Asia. - Map of the Invisible World (2009) - Five Star Billionaire (2013) - The Face: Strangers on a Pier (2016) Kamalia Hasni Kamalia Hasni, better known as Malie, is an emerging Malaysian poet who graduated with a master’s degree in Occupational Psychology from the University of Nottingham. Her first poetry book called An Ocean of Grey was published in 2018 that touches on the pain and aftermath of a love that promised an infinity but ended too soon. In 2020, she released another collection of poetry and prose called A Wave of Dreams, a continuation of her first book that explores the theme of healing and the empowering discovery of self-love. Both her poetry books were published under her own publishing company, Meraki Press. The idea of building her own publishing house along with two of her friends was influenced by their hope to educate the Malaysian community and nurture a love for the English language. She is currently the Digital Marketing Manager of her own company and is currently living in the UK. - An Ocean of Grey - A Wave of Dreams Literary Reading of Malaysia Malay Poetic Forms The Malay oral and literary culture in Singapore is commonly associated with three traditional Malay poetic forms: pantun (rhyming quatrains), syair (narrative poetic form) and gurindam (verses of moral instruction). These expressions are used to convey ideas and life lessons. Traditional Malay poetic forms usually focus on subjects that are didactic in nature, while contemporary Singaporean Malay poetry focuses on social themes such as cultural identity, urban living and traditional ways of life. The use of these themes evokes a sense of belonging and communion amongst those creating and reading these poetic forms, and makes Malay poetry an important form of social expression and identity marker for the Malay community. Contemporary Singaporean Malay poetry has also evolved to take on free modern verse forms called puisi (generic term for poetry) and sajak (literary composition in verse). Traditional Malay poetic forms are also featured in Malay films. The discourse of lovers, for instance, has expressed lyrically through songs structured as pantun or gurindam verses in films. One of the more famous songs with gurindam verses emerging from the industry was Gurindam Jiwa, from the soundtrack of the movie with the same name, composed by Wandly Yazid in 1964. It remains a popular song today, and is performed at cultural events. Three Forms of Traditional Malay Poetry Pantun is a Malay oral poetic form used to express intricate ideas and emotions. Most often a poem in a single quatrain made up of two complete couplets. In Malay, the pantun is a quatrain, rhyming ABAB The following is an example of the pantun: pagi ni hati saya bagai kotak My heart is like a box at primary kotak tanpa barang dan bunyi A box that is soundless or nothing hari ni awal saya tulis sajak As I wrote my poem this early World shall be bright and inspiring cahaya ilham menerangi bumi Syair - is a form of traditional Malay poetry that is made up of four-line stanzas or quatrains. The syair can be a narrative poem, a didactic poem, a poem used to convey ideas on religion or philosophy, or even one to describe a historical event. The syair conveys a continuous idea from one stanza to the next, maintains a unity of idea from the first line to the last line in each stanza, and each stanza is rhymed a-a-a-a-a. The following is an example of the syair: Wahai muda, kenali dirimu, Ialah perahu tamsil tubuhmu, Tiadalah berapa lama hidupmu, Ke akhirat jua kekal diammu. Oh! Young man, knowing you Is like a boat, aren`t you? Living the best out of you And hereafter, you are you! Gurindam - is a type of irregular verse forms of traditional Malay poetry. It is a combination of two clauses where the relative clause forms a line and is thus linked to the second line, or the main clause. Although Gurindam looks similar with Syair which also have the same rhyme at the end of each stanza, it differs in the sense that it completes the message within the same stanza while Syair unfolding the message in several stanzas. The first line of gurindam is known as syarat (condition) and the second line is jawab (answer). The following is an example of the gurindam: Kurang fikir, kurang siasat, Tentu dirimu, kelak tersesat. Fikir dahulu sebelum berkata, Supaya terelak silang-sengketa. Less Tactic, Less thought As you know, you lost Mind your words, as you sought For less dispute, you`ll elute.