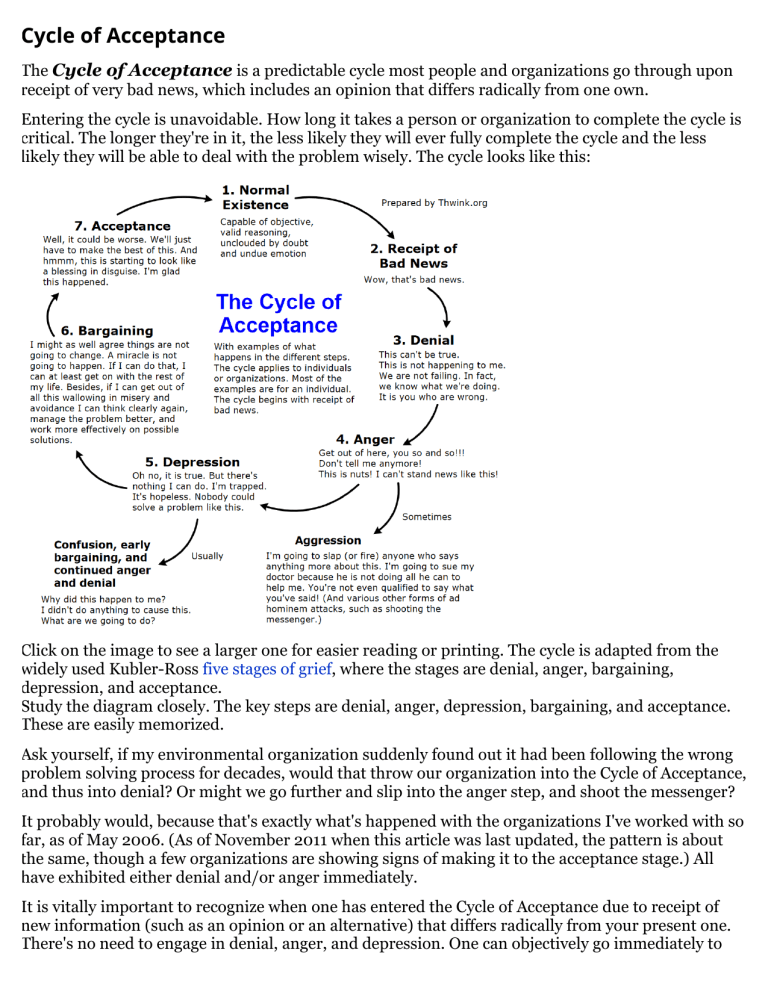

Cycle of Acceptance The Cycle of Acceptance is a predictable cycle most people and organizations go through upon receipt of very bad news, which includes an opinion that differs radically from one own. Entering the cycle is unavoidable. How long it takes a person or organization to complete the cycle is critical. The longer they're in it, the less likely they will ever fully complete the cycle and the less likely they will be able to deal with the problem wisely. The cycle looks like this: Click on the image to see a larger one for easier reading or printing. The cycle is adapted from the widely used Kubler-Ross five stages of grief, where the stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Study the diagram closely. The key steps are denial, anger, depression, bargaining, and acceptance. These are easily memorized. Ask yourself, if my environmental organization suddenly found out it had been following the wrong problem solving process for decades, would that throw our organization into the Cycle of Acceptance, and thus into denial? Or might we go further and slip into the anger step, and shoot the messenger? It probably would, because that's exactly what's happened with the organizations I've worked with so far, as of May 2006. (As of November 2011 when this article was last updated, the pattern is about the same, though a few organizations are showing signs of making it to the acceptance stage.) All have exhibited either denial and/or anger immediately. It is vitally important to recognize when one has entered the Cycle of Acceptance due to receipt of new information (such as an opinion or an alternative) that differs radically from your present one. There's no need to engage in denial, anger, and depression. One can objectively go immediately to the bargaining step. There you calmly weigh the new versus the old, and accept the new that's better and leave the old that's worse behind. For example, here's what one respected environmental leader wrote to me in an email, after I posted a message on a document a forum group was discussing. The forum was moderated. My post was rejected. Here's what the leader said: “Hi Jack, We have been strongly urged by many participants to filter posts that take the discussion afield. I have concerns with your post (most trivially, that the link doesn't seem to be active). Your statement: 'The most basic premise in the article is the one that's never stated. This premise assumes that if a realistic, well justified vision of a New Economy is presented to the right people and resolutions are passed, it will happen.' Not so and I don't know how you could make such inscriptions. Then, (name of forum) comments have to be more than redirecting the group to one's own (or someone else's) more enlightened and superior work. I respect your passion and energy, but perhaps (name of forum) is not right for you. This needs to be a collective endeavor by an extraordinary group that approaches the discourse constructively and humbly. All the best, (name).” Note the strong denial and the rationalization used to justify his position. My post included an attached document which analyzed the document the group was discussing. It presented clear, compelling reasons the implied premise was unsound. The link was to the paper on Change Resistance as the Crux of the Environmental Sustainability Problem. The link was working. But when a person is in a state of denial and anger, not everything works. Note also the aggression in "more enlightened and superior work." As another example, here's what a mid-level manager of a major environmental organization had to say to me, after reading part one of the manuscript to Analytical Activism. The manager has an MBA and thus should perhaps not be so easily led astray: “I realize from your perspective that the environmental movement might look like a failure and our approaches irrational; however from my perspective it does not. It is a work in progress that I am delighted to participate in. There have been and continue to be many successes, some small and some major. Because you are working outside of the movement and are at home, you do not see the progress. You see the failures because they are more widely reported.” This is denial. Here's what the CEO of the same organization, which has over 300 employees, wrote me, after reading the same material: “…an organization like the [name of organization] is unlikely to embrace an entire new approach at once, however valid. I think you and your colleagues will feel less frustrated, and will make more rapid progress, if you seek to influence the ongoing dialogues on various issues within the [name of organization] as well as offering your own entirely new approach. …this is an organization that often responds better to a series of coordinated, incremental nudges than to a big, bold, new idea.” However carefully worded this may be, it is also denial. But it gets worse. The same person, after the majority of their members' delegates voted for "a new way of thinking" at a national convention, wrote me: “I guess I really couldn't tell you what the vote for a new way of thinking meant -- it came out of the blue for me and was not expected. But I do think it indicates that people are open to new approaches -- but I did hear from several people that your proposal struck them as overly complex and difficult to implement in a grass-roots organization so you may want to try to create a much simpler presentation -- you may be losing people in the details.” Step 3: Denial - This is more denial. The executive is clearly rejecting the new way of thinking that his own organization wants and the new approaches I have offered as well. In both passages, he justifies his position with a rationalization. In the first passage it is that I am not following proper channels or "ongoing dialogues." In the second passage the rationalization is that my "proposal" is "overly complex and difficult to implement." Neither is true, because as an experienced business consultant I have seen a completely different reaction from business managers to similar documents and face to face discussions of mine. Their reaction to the bad news of a poor assessment, presented with alternatives on how to improve, was to eagerly accept the bad news and move right into discussing how to best pursue the alternatives to improvement. Step 4: Anger - And then there is anger. The day one mid level environmental organization manager (who was also a professor at Yale University) read an analysis of mine that pointed out that organization was failing to achieve its objectives and offered a better way, that person called me up and proceeded to scold me for about 40 minutes. In their opinion, I didn't know enough about their organization to say what I said, and I should not say it anyhow, because it had not been agreed upon by them, and they've been having problems and are aware of them, and how do you get volunteers to do anything anyhow, and so on. They were so angry the phone just about melted in my hand. Whenever I tried to say anything, I was quickly interrupted. I've never had a call like this before, so we have definitely touched a raw nerve. But this is a known phenomenon. It is the anger stage of the Cycle of Acceptance. Anger directed toward the bearer of bad news is known as shooting the messenger, which is a type of ad hominem argument. Step 5: Depression - The depression step for organizations is similar to depression for people, who withdraw into their own world. This is similar to the way some organizations start to keep as much as possible secret, or do lots of work internally and little externally, so as to avoid confrontation and criticism, and to create a sense of importance and self-worth. There is a lot of dysfunctional behavior associated with depression in people and organizations. It takes many forms. Basically it seems to be avoidance of the truth, so that the truth is less painful. Step 6: Bargaining - In the bargaining step an organization starts to question itself, such as: "Maybe this bad news has some truth to it, don't you think? What might happen if it was true? I don't think we should be embarrassed that we failed in the past. It was a tough problem. But you know, I would be even more embarrassed if we failed to see that maybe this bad news is in some way good news. For example, this assessment that shows why we have done such a poor job for the last several decades seems to have a few valid points. It's not all wrong. I think that maybe we should at least take a look at some of the things in it that may be true." Step 7: Acceptance - Bargaining leads to the acceptance step. Basically, acceptance in the business world means admitting that you made a mistake or an undesirable situation is not going to go away, or both. Extremely mature managers and organizations arrive at the acceptance step almost instantly by skipping the other steps, because they are such a waste of time and energy. You can too, once you know the Cycle of Acceptance for what it is. Only after bad news is fully accepted can an organization begin to deal effectively with how to best adapt to change. After reading the material on Thwink.org, where are you and your organization in the Cycle of Acceptance? The 6 Stages of Change: Worksheets for Helping Your Clients Jeremy Sutton, Ph.D. 06-12-2021 It was Dean Karnazes’s 30th birthday, and he felt trapped. Despite a successful career and a happy marriage, he was lost and disillusioned. That evening, he was drunk and out with friends at a night club in San Francisco when a beautiful young woman approached him. They hit it off instantly. One way or another, what he decided next would determine his future. Perhaps unexpectedly, he made his excuses and left. Once home, he rooted through boxes, took out an old pair of sneakers, and did something he hadn’t done since college: he started running (Karnazes, 2006). And he carried on, and on, becoming famous for winning several ultra-marathons and running across America. He has since been named as one of the “Top 100 Most Influential People in the World” by Time magazine. Change can take many forms. Sometimes we choose it, and sometimes it just happens. The Transtheoretical Model of Change explains the stages we pass through when we change our behavior and provides the insights we need to intervene and move on in life. In this article, we look at the model, explore the stages and multiple factors involved in change, and identify worksheets that can help you or your client. Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change. This article contains: • • • • • • • • • • • • • What Are the Stages of Change? Stage 1: Precontemplation Stage 2: Contemplation Stage 3: Preparation Stage 4: Action Stage 5: Maintenance Stage 6: Relapse Stage 7: Termination 5 Worksheets to Aid Your Clients’ Process 4 Ways to Use Motivational Interviewing PositivePsychology.com Resources A Take-Home Message References What Are the Stages of Change? The Transtheoretical Model of Change (TTM) – the result of the analysis of more than 300 psychotherapy theories – was initially developed in 1977 by James Prochaska of the University of Rhode Island and Carlo Di Clemente (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). The TTM offers a theory of healthy behavior adoption and its progression through six different stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and termination. TTM is a model, rather than a single method for change, combining four key constructs and a temporal dimension – not present in other theories at that time – that can help a client understand behavioral transformation. • Stages of change Each of the six stages must be completed in order to implement behavioral change into a client’s lifestyle. • Processes of change Ten processes capture the critical mechanisms for driving change. • Critical markers of change Beliefs and confidence develop as a client moves through the stages. • Context of change Factors such as risk, resources, and obstacles provide context and influence change. How do we progress through change? Our perception of change – for example, altering our diet or increasing exercise – transforms over time. In earlier stages, we see more cons than pros, but over time, in later stages, the balance shifts, and we start to see increased benefits to behavioral change. The model helps us understand not only the process by which clients make an intentional change, but also the support from themselves and others that can help. As such, it provides a useful tool for therapists, counselors, and health professionals working with clients and patients. TTM identifies six stages of readiness experienced by an individual attempting to change (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997; Liu, Kueh, Arifin, Kim, & Kuan, 2018): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Precontemplation – failing to recognize the need for change Contemplation – seriously considering the need for change Preparation – making small changes Action – exercising for less than six months Maintenance – regular exercise lasting longer than six months Termination The final stage, termination, is perhaps more of a destination – an end state. At this point, even if bored or depressed, the client will not return to their former way of coping (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). However, it is essential to note that the client’s behavior through earlier stages may not be linear. Instead, it occurs in cycles; they may revisit – or relapse – to prior stages before moving on to the next. An individual may maintain their diet for months, but then on vacation, return to their old ways. After several weeks, they may start re-considering returning to their new diet or seek out other options. What influences change? Many factors impact – strengthening or weakening – the client’s ability to change. TTM lists 10 processes that assist the progression between these stages; important ones include self-efficacy, decisional balance, and temptations. Indeed, self-efficacy – the belief in our ability to change – is crucial to planning and executing the actions required to meet the goals we set and fight the temptation to relapse (Luszczynska, Diehl, Gutiérrez-Dona, Kuusinen, & Schwarzer, 2004). As a result, clients high in self-efficacy are better at accepting challenges and persisting in overcoming obstacles. The individual’s perception of the positive and negative aspects of modifying their behavior is also crucial to success. They must balance the pros and cons to decide whether to continue the journey, fall back, or give in. Successful change requires the client to believe that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. But there is help at hand. Indeed, interventions based on the TTM have resulted in substantial improvements when applied across multiple disciplines, including the workplace and health settings (Liu et al., 2018; Freitas et al., 2020). Next, we review the six stages of change to understand what it means to be in each, its goal, and the tasks that, when completed, help a person move to the next (guided by Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). Stage 1: Precontemplation “I don’t need to change.” Client status Change is not wanted, needed, or possible. Client goal Seriously consider the need for behavioral change. Description The Precontemplation stage occurs when the client has no intention, now, or in the future (typically seen as six months), to change their behavior. For example, “I have no intention of taking up a sport or going running.” Most likely, they are either under-informed or uninformed. The client is either completely unaware or lacking details regarding the health benefits of changing their behavior and taking up physical exercise. Perhaps they tried previously, with little apparent success, and have become demoralized or despondent. Tasks • • • Increase client awareness of why change is needed. Discuss the risks regarding their current behavior. Get the client to consider the possibility of change. Stage 2: Contemplation “I might change.” Client status Procrastination. The client intends to make the change within six months. Client goal Commit to change in the immediate future. Description The client has become acutely aware of the pros of making the change, but they are also keenly aware of the cons. For example, “I know I need to lose weight for my health, but I enjoy fast food.” Balancing the costs versus the benefits can lead to ambivalence – mixed and contradictory feelings – that cause the client to become stuck, often for an extended period. Tasks • • • Consider the pros and cons of existing behavior. Weigh up the pros and cons of the new behavior. Identify obstacles to change. Stage 3: Preparation “I will change. Really!!” Client status Committed to changing their behavior. Client goal Develop an action plan to organize resources and develop strategies to make the changes happen. Description The client intends to move to the action stage soon – typically within the next month – but they are not there yet. For example, “I need to understand what support is available and put it in place before I stop smoking.” The client typically begins to put actions in place, for example, starting a gym membership, joining a class, or engaging with a personal trainer. Tasks • • • Increase the client’s commitment. Write down the client’s goals. Develop a change plan. Stage 4: Action “I have started to change.” Client status The plan has taken effect, actions are underway, and a new pattern of behavior is forming. Client goal The new behavioral pattern has remained in place for a reasonable length of time (typically six months). Description The client has made good progress; they have modified their lifestyle over the last six months. For example, “I go to the gym on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays every week, and I am following a plan set out by my trainer.” Their new behavior is observable by other people, whether it’s exercising, eating more healthily, or no longer smoking. Tasks • • • • Implement the plan. Revisit and revise the plan if needed. Overcome difficulties and maintain the commitment. Reward successes. Stage 5: Maintenance “I’ve changed.” Client status A new pattern of behavior has been sustained for a reasonable amount of time and is now part of the client’s lifestyle. Client goal Sustain the new behavior for the long term. Description Within the maintenance stage, the client becomes confident they can continue their new lifestyle, and the behavioral change is embedded in their lives. Perhaps equally important, they are less likely to relapse – to fall or slip back into their old selves. For example, “I am confident I can make healthy eating choices at home, work, or when I go out.” Based on data from both self-efficacy and temptation studies, maintenance can last between six months and five years (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). Tasks • • • • Maintain behavior across multiple situations. Continue integration into life. Develop coping strategies. Avoid regression or relapse into old ways. Stage 6: Relapse “I’ve returned to my old ways.” Client status Returned to an earlier stage. Client goal Reaffirm commitment and begin progressing through each stage again. Description A relapse is a form of regression to an earlier stage. It is not a stage in itself, but a failure to maintain the existing position in behavioral change, either as a result of inaction (e.g., stopping physical activity) or the wrong activity (e.g., beginning smoking again.) Unfortunately, relapse is typical for many health-related behavioral changes. But it is not inevitable. For example, “I was out the other night and started smoking. I’ve continued since.” The smoker begins smoking, the new runner gives up, the diet is over, fast food is back on the menu. Tasks • • • Identify the triggers linked to relapse. Reaffirm commitment to change. Revisit the tasks associated with the stage the client has returned to. Stage 7: Termination “ I am changed forever.” Client status The temptation to return to old ways of behavior is no longer present. Client goal None required; behavioral change is part of who the client is. Description Success. The client has zero temptation, and their self-efficacy is 100%. They will not return to their old ways, for example, if they argue with their partner, are unhappy with work, or dent their car. The unhealthy habit is no longer a part of their way of coping. Instead, the new behavior is part of the person’s identity and lifestyle and has persisted for a long time. For example, “I have been keeping up with physical exercise for some years now, and even after recovering from a long-term injury, I continue to do so.” Tasks • None required. The client’s old ways are in the past. Note that an alternative view is that termination is never reached. There is always a risk of relapse into prior unhealthy ways, even several years down the line. In this picture, the individual only ever remains in the maintenance stage. 5 Worksheets to Aid Your Clients’ Process The following worksheets support the client in planning, implementing, and maintaining behavioral change: The five A model The five A framework was created to help smoking cessation but has since been successful in the management of other negative health habits (e.g., excessive drinking, lack of exercise, and substance abuse). 5 As Ask Advise Agree Assist Instruction Use a simple question to collect and analyze information about the client, e.g., identify tobacco use. Identify the behavioral change required and suggest that the client make that change, e.g., recommend the smoker considers stopping. Determine the stage of change the client is in, e.g., is the smoker prepared to attempt to stop? Assistance needs to be appropriate to stage the client is in, e.g., use counseling, training, or pharmacotherapy to help them quit. Arrange activities inside and outside of consultation, Arrange e.g., schedule follow-up appointments, refer them to another resource, and monitor change. Decisional Balance Worksheets Changes are most effective when there is motivation and ‘buy-in’ from the client. The Decisional Balance Worksheet provides an excellent way of capturing pros versus cons involving a change under discussion. Stages of Change The Stages of Change worksheet is a free download to educate the client about the stages involved in behavioral transformation and relapse. Relapse Prevention Plan The Relapse Prevention Plan provides a useful resource to capture coping skills and social support, along with the potential impact of relapse in behavior. Goal Setting Goal Setting is crucial to any transformation. It provides focus, tracks progress, and ensures appropriate support and resources are in place for success. Our SMART Goals Worksheet offers a valuable tool for defining and documenting realistic, achievable, and time-bound goals. 4 Ways to Use Motivational Interviewing Motivational interviewing can be used with the client to overcome feelings of ambivalence and find the self-motivation needed to change their behavior (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). The approach has proven successful as an intervention for managing health conditions and overcoming addiction. The OARS acronym offers guidance for a set of basic questions to be used early and on an ongoing basic in an interview: Open questions Invite someone to tell their story, without leading or directing them. How can I help you with… ? What have you tried before to make a change? Affirmations Acknowledge someone’s strengths and behaviors that lead to positive change. That’s a great idea. I’ve enjoyed talking with you today. Reflective listening Listening well is essential to building trust, engagement, and developing the motivation required to change. Focus on the real message being spoken by repeating or rephrasing what has been said. So you feel that… Are you wondering whether…? Summaries This is a particular way of using reflective listening, often at the end of discussing a topic or when the interview is about to finish. So, from what I understand so far … This is what I’ve heard; please let me know if I’ve missed anything. The answers to the above questions feed into the process of planning with the client. PositivePsychology.com Resources The following resources will help your client progress through the six stages, reducing the likelihood of relapse. Basic needs satisfaction Meeting basic psychological needs can help the client avoid becoming stuck and unable to proceed with positive behavioral changes. WDEP questions worksheet Use this list of questions to help a client understand what they Want, what they are Doing, Evaluate if it is working, and follow their Plan to change things for the better. Abstraction worksheet Download and complete this worksheet to identify the behavior to be changed, understand the steps to get there, and visualize how it will look. Self-Directed Speech Worksheet Use the client’s inner voice to motivate them to make changes in their life, with this SelfDirected Speech Worksheet. Reward Replacement Worksheet Identify and document the rewards that will arise from a change in behavior to motivate the client. Self-Contract Helping the client write a self-contract for the changes they wish to make can be an effective way of forming a commitment. Implementation Intentions We often fail to act on our good intentions. If–then planning can offer an effective strategy to turn goals into action. Building Self-Efficacy by Taking Small Steps Self-efficacy can grow over time as a result of a cycle of achievement and building confidence. This tool helps the client pursue their goals, starting with small steps. Leaving the Comfort Zone Growth mindsets must be translated into action, usually outside of the comfort zone. This visual tool helps the client weigh up the costs and benefits. 17 Motivation & Goal-Achievement Exercises If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others reach their goals, this collection contains 17 validated motivation & goals-achievement tools for practitioners. Use them to help others turn their dreams into reality by applying the latest science-based behavioral change techniques. A Take-Home Message At times we lose our way. We don’t always eat well, exercise regularly, drink enough water, take time to learn, put our phone down, and spend time with our friends and family. We need to change. But often we are unaware or ill-informed about what’s wrong or don’t know how to begin the process. Understanding the steps to personal transformation is a great place to start and where the TTM can help. The six stages of the model may not always closely map to our behavioral change, the progression between stages may seem unclear and the reasons for relapse ill-defined, but it can help you achieve your goals. The TTM offers us insights into the journey we must take to move from where we are now, to where we want to be, by describing a useful abstraction of what is going on when we talk about change. The model provides a lens through which we can view ourselves and our clients. Ask yourself: What do I want to change? Am I ready to start? What stage am I at in my journey? Use the answers, along with the TTM, the tools provided, and support from family and friends to push forward with the changes you want in life. We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.