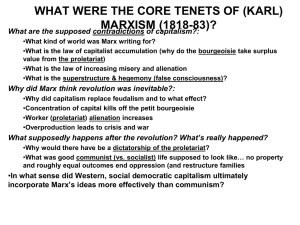

Ellen Nelson March 21, 2022 POLS 3062 Week 9 Reflection Marx & Engels, The Manifesto of the Communist Party, Part 1 and 2 Written in 1848, The Manifesto of the Communist Party, or the Communist Manifesto, may be considered one of the world’s most influential political documents. Published as the 1848 Revolutions began, the pamphlet presents an analysis of the class struggle that was then present and hypothesized to be existent until revolutionary action. It also examined the conflicts of capitalism and its subsequent mode of production. Authors Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels summarize their theories of society and politics, most notably the idea that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle.” In reading their accounts, I found the remarks of Part 2 to be the most compelling reflections of democracy in America and will thus be the focus of this reflection. After examining the nature of the ruling class in Part 1, the Manifesto turns to its subordinate counterpart- the proletariat. Since its creation, the proletariat has endured massive struggle with the bourgeoisie. According to Marx and Engels, the original struggle pertained to the individual laborer, later involving groups of workers, who rebelled against the exploitation of the ruling class. As industry developed, however, the proletariat became increasingly concentrated as distinctions among laborers began to dissolve. The authors assert that the proletarians are the only revolutionary class, as their exploitation is fundamental to the foundations of society. With this assumption in mind, I sought to consider the implications of revolution by the proletariat in modern America. More specifically, I considered the impact of a revolution on America’s most marginalized communities. While united by class, other demographics of proletarians vary immensely; differences in race, age, gender, and wealth, among others, contribute to a party in which there is very little common ground. Thus, a revolution that may be possible to the most secure members of society may not be feasible by others. The insecurity that would erupt from such a revolution may severely displace disenfranchised populations on multiple fronts, including those political, social, and economical. It then follows that the details of revolution must be taken into account; how likely is the revolution to succeed? How long would it last? Do the outcomes of a revolution validate temporary displacement? To me, revolutionary action is not feasible. America’s most vulnerable populations are far too at risk to carry out Marx’s dreams. To act in such a way would be selfish; relatively secure members of the proletariat would jeopardize the safety of their fellow workers in the name of a revolution that does not guarantee success. While Marx and Engel’s ideas may have been relevant more than a century ago, I do not think they are applicable to the modern era.