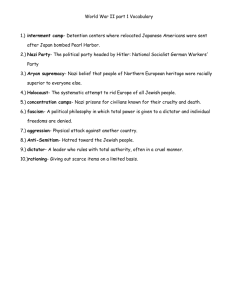

Batch : 11th Department: English Semester: 5th Assignment prepared by : Rimsha Rahin Sidra Shero Kaynat Maheen Author's Introduction Benjamin wilkomirski Benjamin wilkomirski was born on February 1941 in Latvia , migrated towards Switzerland after world war II .He was a classical musician and also wrote a book "Fragments:Memories of wartime childhood " about a holocaust survivor and plived in Nazi concentration camps who suffered a lot . However, he was adopted by a Dössekker's couple in 1945. According to Benjamin he underwent psychotherapy in order to recover his childhood memories. His book gathered a lot of fame. This book also got a "Jewish book award". Everything in Benjamin's life was going well until Daniel Ganzfried a jewish journalist smelt a rat while taking an interview with Benjamin. Actually Ganzfried himself wrote an account on his father's experience in Auschwitz so he didn't believe Benjamin's account. Then the journalist decided to dig deeper , what he discovered was astonishing that Benjamin was not a Latvian.He was born in a village near swiss capital in 1941,his mother was unmarried and placed her son "Bruno'' in an orphanage in 1945 he was then adopted by a Dössekker couple and lived a prosperous life in Zurich. He had never been in a concentration camp except as a tourist. He was not even a jew. After disclosure of the truth many Jewish organisations started to distance themselves from Benjamin. So it was debunked that Benjamin's real name was Bruno and the memoir he told was not his own story. After that his book got banned and then Benjamin or Bruno came into a never-ending downfall. Background : Nazi Party On November 9, 1938, in an event that would foreshadow the Holocaust, German Nazis launch a campaign of terror against Jewish people and their homes and businesses in Germany and Austria. Propaganda in Nazi Germany was the practice of state directed communication to promote German nationalism, the goals of the Nazi Party of Germany, and the party itself. The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's leadership of Nazi Germany (1933–1945) was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi policies. Holocaust The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some "six million Jews across German-occupied Europe", around two-thirds of Europe's Jewish population. Adolf Hitler ( leader of the Nazi Party) Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 Invasions The German Nazis mounted the greatest invasion in history. Germany defeated and occupied Poland (attacked in September 1939), Denmark (April 1940), Norway (April 1940), Belgium (May 1940), the Netherlands (May 1940), Luxembourg (May 1940), France (May 1940), Yugoslavia (April 1941), and Greece (April 1941). Major Characters :Benjamin Wilkomirski • He is the narrator of this book . • He is recalling his childhood and adulthood • His father was brutally killed in front of him • Lost his whole family • His initial language problems • His childhood in Nazi's death camps • His unforgettable and painful childhood • His survival in camps, orphanage and his new family (Dössekkers) • His profession • Societal thinking •Children have no memories, Children forget quickly Jankl • The only friend of Binjamin in those barracks •He was a good and sensitive boy •He was 12 when Benjamin was brought there • He was a protector, adviser and teacher of Benjamin • He always shared food with Binjamin, which he stole from the camps • He was a friend of Benjamin and the only hope he had in that dark days • He dies in the middle of the story in the Nazi Camps Salvo Berkovici • He was Benjamin's teacher • He studied music, physics, mathematics, philosophy and medicine • Benjamin's mentor and guide • A fatherly figure to Benjamin Mila •She was older than Binjamin • They were in the orphanage • She got separated from her mother • She always helped Benjamin to escape from the boys in the orphanage • She grew up and started working as a translator • Her mother died in between that time period • She and Binjamin were both the survivors • They loved each other •tThey lost each other Summary: In this book memories of World War II is presented in a fractured manner , an overwhelmed, very young Jewish child narrates his own story . His first memory is of a man being crushed by uniformed men against the wall of a house; the narrator is seemingly too young for a more precise recollection, but the reader is led to infer that this is his father. Later on, the narrator and his brother hide out in a farmhouse in Poland before being arrested and interned in two Nazi concentration camps, where he meets his dying mother for the last time. After his liberation from the death camps, he is brought to an orphanage in Kraków and, finally, to Switzerland where he lives for decades before being able to reconstruct his fragmented past. If you don't remember where you came from, you will never really be able to know where you're going. I survived; quite a lot of other children did too. The plan was for us to die, not survive. Wilkomirski was 3 or 4 years old, he thinks -- there are no certainties within this work -- when his family was uprooted from their home somewhere in Eastern Europe. After a period of flight in which he was a witness to his father's execution, Benjamin was separated from his brothers and his mother and transported to Majdanek, the first of several camps in which he spent the next four years. From now on I have to manage without you, I'm alone. It takes a while for me to feel I'm able to look over there, but the man is gone. Nothing there to see anymore but a little mound of clothes, blood, and snow on the side of the road. "Found wandering on the outskirts of AuschwitzBirkenau in the closing days of World War II ," according to notes provided by his publisher, he was taken to an orphanage in Krakow and subsequently resettled at another orphanage in Switzerland. Fragments records what Wilkomirski calls the "shards of memory with...knife-sharp edges" that remain to him from roughly 1939 to 1948. He does not, however, try to reconstruct an ordered sequence for these memories. "If I'm going to write about it, I have to give up the...logic of grown-ups," he tells us. "It would only distort what happened." Thus, for example, we are never told, because the child when he was a child did not know, where he lived before the war. Krakow is mentioned several times, and Riga once, though all he recalls with certainty of Riga is "a cry of terror" in "a staircase" and the warning, "Watch it: Latvian militia." We get the sense of a crowded train, a long journey, "terrible thirst" and "some vague hope" that has "something to do with Lemberg." But, speaking always from the perspective of a child, he says, "I don't know what Lemberg is. It's some kind of magic word.... Maybe someone we have to find...who's going to help." Help is not going to come. "We never reached Lemberg," the child tells us quietly. The details of life within the camp are vividly recaptured. Four boys sleep together on a strawfilled mattress in a bunk.Between two rows of bunks there is a space in which, at first, the children are allowed to defecate. Binjamin learns to stand within the pool of excrement to keep his feet from freezing. Later, a bucket is brought in, but it fills up so quickly that the children, who are plagued with diarrhoea, have to struggle upon pain of death to hold their bowels. A child who pees in his bed is executed in the morning. The guards are seen as "uniforms," some black, some gray, some "brownish-green," and are, by turn, goodnatured and then murderous. One of the guards, "a powerful, bull-necked man" with "thick, strong arms,"takes off his jacket and plays kickball with the children, then suddenly lifts the "ball," a heavy wooden sphere, and smashes it into the skull of a small child, who dies instantly. Another guard, a female, beckons Binjamin one day: "Today you can see your mother." Escorted to another building, he's directed to "a body under a grey cover." When the cover moves, he sees "a woman's head" and "then two arms."The woman, he remembers, "seemed to smile." Then, "groping with her hand under the straw" on which she lay, she "motioned for me to come closer." Unable to speak, "she reached out her hand to me and indicated that I should take what she had brought out from under the straw.... I to ok the object, clutched it against me, and went toward the door." Only when he reached his barracks did he realise that her gift to him had been a piece of hardened bread. The book is built on isolated incidents like these, semi-understood but unforgettable epiphanies rather than clearly recognized "events." Two small bundles are thrown on the floor of the children's barracks one cold night. Peering over the edge of his bunk, Binjamin sees that they are "tiny babies," still alive. By morning, the babies' blackened fingers have become "white sticks " because they chewed their frozen flesh down to the bone before they died. Binjamin does not know why he survived. The only explanation that he can provide involves the kindness of an older boy named Jankl who slept with him on his mattress. "Jankl was good.... He knew how to steal food.... He always shared. Jankl was my friend. … I owe my life to Jankl." The book moves back and forth between the years within the death camps and the years in Switzerland. No line is drawn between the two experiences. The terrors that the child undergoes as victim of the guards at Majdanek are, in fact, exceeded frequently by those he undergoes as victim of the dangerous solicitude of philanthropic grown-ups. Placed in a foster home in Switzerland, he panics at the insistence of his foster parents that he give up all the strategies of self-protection that he has acquired in the Nazi camps. Those strategies, he has reason to believe, had served him well. With Jankl's help, he had invented useful tools to deal with evil. But he has no tools, no skills, no strategies, to cope with the banality of good intentions. School was full of talk, but nobody had the faintest idea about life-still less about death-not even the teacher! I often used to go back and visit my first great physics teacher, Salvo Berkovici, although I'd been studying in another city for a long time by then. He was an old man, and a wise one. The last surviving member of a centuries-old family of Romanian rabbis, he had studied, among other things, music, physics, mathematics, philosophy, and medicine. He was my guide and mentor, the kind of father I would have wished for myself. He was the only person with whom I could be open. He was the only person back then who understood if all I could dare to hint at past events. He understood what I was really saying. It was the Nazis, he makes clear, who taught him the most lasting lesson of his life: "Friendly grownups are the most dangerous. They're best at fooling you." He had fought hard to adhere to this belief and became frantic when he was compelled to let down his defences. "I was always being forbidden to stick to the most important rules of survival." When he stole food in the orphanage, he says, "they always found my hiding places.... Oddly, they didn't punish me, at least not right away.... What were they planning?" His foster family later told him that the concentration camp had not been real, that "it was all a dream," but he was wise enough to have rejected this benighted, unconvincing explanation. His own belief, at least for a long time, was that "the camp's still there -- just hidden and...disguised. They've taken off their uniforms'' but "they can still kill." The flames that he sees through the door of a coal furnace in the basement of his foster family's home fill him with fear as great as any that he felt while he was living next to the gas ovens. "The oven door is smaller than usual," he notes, "but it's big enough for children." It is so easy to make a child mistrust his own reflections, to take away his voice. I wanted my own certainty back, and I wanted my voice back, so I began to write. "Over there, in the fields'' beyond the camp, the child says, "there was a world once, but it disappeared." Leaving the camp at war's end is, for this reason, deeply problematic for the child's understanding: "How can you go somewhere...that no longer exists?" As he finally leaves, he says, "We're on our way to nothing... the world's over." The book ends with no salutary message and no artificial affirmation about human goodness. Only by writing this extraordinary book, by speaking as a witness to the death of faith, does Wilkomirski win a kind of victory at last and voice a final, although fragile, affirmation. The child, in all but physical respects, died long ago. He died at Majdanek and then a second time in Switzerland. The man survives somehow -- we don't know how, his sanity seems like a miracle -- and leaves this gift of nearly perfect pain and beauty to a world still willing to destroy the innocent.