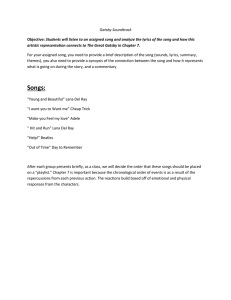

Music and Health Assignment Motivating and Ergogenic Playlist to Promote Physical Health Name: Karl Hemmings Student ID: 1085371 Word Count: 2192 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 As an ardent and dedicated competitive powerlifter with over six years of strength training under my belt, I have personally experienced the ergogenic effects music has on my training. As expected, the effects are not limited to anecdotal evidence, with Karageorghis et al. (2013), finding that music listening during exercise can enhance physical performance, strength and power, whilst simultaneously reducing fatigue. In powerlifting, an immense amount of physical exertion takes place as a large stress is placed on the body. Therefore, the playlist I have tactically crafted, aims to motivate myself to continuously push my limits as well as boost my athletic performance resulting in improved physical health. To facilitate the creation of my playlist, I segmented my training session into five stages, specifically, warm-up, squats, bench press, deadlifts and cool down. Next, I participated in the process of active music listening to examine and reflect upon my current gym playlist of more than 100 songs (Gault, 2011). This process entailed analysing both the musical elements, namely, rhythm, volume, tempo and melody, as well as non-musical elements, lyrics and personal associations. Over the course of a few weeks, I successfully narrowed down my original playlist to the 20 songs I found to be highly motivating with ergogenic qualities. To perfectly align the playlist to my training session, I sorted the potential songs into five groups based on their musical characteristics as well as non-musical features and aligned each group with a specific section of my workout. I trialled these five ‘sub-playlists’ throughout my regular training sessions and analysed each song using the framework of the Brunel Music Rating Inventory 2 (BMRI-2). This rating system quantifies the degree to which a piece of music motivates the listener to exercise more intensively (Karageogrhis, Priest, Terry, Chatzisarantis & Lane, 2006). Based on a predetermined timeframe for each stage of my workout, I used a combination of my ratings from the BMRI-2 as well as consideration of the non-musical elements to determine which songs to include within each section of the workout. I selected two songs for each of the 5 stages of my workout and this resulted in a playlist length of 52 minutes which corresponds with the time I usually exercise for. I selected the first warm-up song based on its ability to effectively stimulate physiological arousal, which results in heightened motivation to work out intensively (Bishop, Karageorghis & Loizou, 2007). The second warm-up song was chosen due to its ability to evoke positive nostalgic associations which generate individualistic motivation. Next, is the central and most physically 2 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 demanding portion of my workout, that is the squat, bench press and deadlift. For this section, I selected the six songs with the highest BMRI-2 ratings, that is, these songs had an upbeat rhythm, fast tempo, euphoric melody and hence significant motivating and ergogenic effect, enabling me to perform to the highest possible degree. A study by Karageogrhis et al. (2006) found that listening to motivational music while exercising accrues psychophysical benefits such as decreased rate of perceived exertion (RPE), improved affective states and optimal arousal levels. To conclude, I selected my first cool down song based on its highly euphoric lyrics and melody which generate an improved psychological state and promote exercise adherence. My second and final song serves to maintain a degree of physiological arousal through its medium tempo and create a perfect ending to my workout with its beautifully textured chord progressions that generate a comforting and optimistic psychological effect (Kelley, Andrick, Benzenbower & Devia, 2014). 1. Hale, N.D., Mathers, M.B., III. & May, B.H. (2002). Till I Collapse [Recorded by Eminem featuring Nate Dogg]. On The Eminem Show [Record]. Santa Monica, CA: Aftermath Records. (2001). My playlist begins with the ultimate pump up song ‘Till I Collapse’ by Eminem, chosen because of its highly motivating lyrics. The song’s intro depicts the universal theme of abandoning one’s goals during times of difficulty through “when you feel weak you feel like you just wanna give up”. Given the strenuous nature of powerlifting, I occasionally enter the gym spiritless and demotivated but as I hear Eminem shout “motivation to not give up and not be a quitter”, I am immediately motivated to work out as hard as possible. This motivating effect comes from the song’s ability to successfully stimulate physiological arousal and help me mentally envision a successful workout. This is supported by Karageorghis and Priest (2012) who found that pre-task music can optimise arousal and encourage task-specific motivational imagery. 2. Booker, S., Newman, W.J. & Spencer, M. (2013). Love Me Again [Recorded by John Newman]. On Tribute [MP3]. Jamaica: Universal Island Records. (2012). For my dynamic warm-up, ‘Love Me Again’ by John Newman was chosen due to its unique ability to induce positive reminiscences and personal associations. The song brings me back to the time I spent playing FIFA 14 and repeatedly heard this song on the game’s soundtrack. Given my innate desire to be the best, I was an extremely competitive gamer and consequently associate this song with a desire and motivation to succeed highly. Barrett et al. (2010) found associations induced by 3 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 music often represent a form of nostalgia, and for me the memories positively motivate me to ‘smash’ my upcoming workout. Additionally, hearing this song on the FIFA 14 soundtrack corresponds to the time in which I began strength training and hence enables me to reflect on how far I have come with my training. 3. Prydz, E. (2015). Opus [Recorded by Eric Prydz]. On Opus [MP3]. Hollywood, CA: Virgin Records. Commencing the strength training portion of my workout, for my increasingly heavier, warm up sets, I have chosen ‘Opus’ by Eric Prydz because of its distinctive progressive tempo and increasing volume which engenders ergogenic effects. Szabo, Small and Leigh (1999) argued that music with an increasing tempo results in increased work output and distraction from fatigue. In addition, Corigliano (2017) found a positive correlation between the volume of music and its ability to yield performance enhancing benefits such as decreased RPE and enhanced muscular endurance. Lastly, the progressive nature of the song enables me to properly pace myself through my lifting sets and increase my intensity purposefully in order to avoid injury. 4. Larsen, P. & Stokes, D. (2012). Beating of My Heart (Mattisee & Sadko Radio Remix) [Recorded by M-3ox]. On Beating of My Heart [MP3]. Los Angeles, CA: Warner Dance Labels. Continuing with squats, I have chosen ‘Beating of My Heart’ by M-3ox because of its volume fluctuations and climactic upbeat tempo. I find these produce performance enhancing effects. Throughout the song, volume and tempo follow a cyclical structure familiar to pop songs of increasing before a ‘drop’ and then building back up again (McFerran, 2019). This predictability allows me to align my sets with the stimulative ‘build up’ of the song and my rest time with the softer volume and slower tempo portions of the song. By aligning my sets with the music, I felt the ergogenic effects of enhanced work output and improved strength and power during my training. This is supported by Papa (1990) who concluded significant improvements in strength output in the presence of stimulative music. 4 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 5. Ferguson, D.B., Jr. & Marenyi, T. (2019). REDLIGHT (Holy Goof Remix) [Recorded by Holy Goof]. On REDLIGHT [MP3]. New York City, NY: Ultra Records. Moving onto my second exercise, the bench press, I have chosen ‘Redlight’ by Holy Goof on account of its exuberant, adrenaline-spiked bassline and 130 beats-per-minute (BPM) tempo which is conducive in promoting psychophysical benefits of lowered RPE and heightened motivation. To support this claim, van Dyck et al. (2017) reported that an upbeat tempo was the most significant determinant in generating a psychophysical musical response. In addition, McCown, Kesier, Mulhearn and Williamson (1997) found that listening to music with an exaggerated bass during high intensity training resulted in strong motivational responses. Personally, this song is the catchiest in this playlist, which results in peak motivation levels as I reach the midpoint of my workout. Moreover, Ballmann et al. (2019) found that preferred music amplified one’s motivation to continue exercising and lowered RPE through its distracting effect. 6. Luyks, T. & Soest, K.V. (2008). Nobody Said It Was Easy [Recorded by Evil Activities]. On Evilution [Record]. Netherlands: Neophyte Records. Continuing with bench press, I selected ‘Nobody Said It Was Easy’ by Evil Activities due to its strong rhythm, rapid tempo and hardcore style which together motivate me to exercise harder throughout the latter part of my workout. Clark, Baker, Peiris, Shoebridge and Talor (2016) found that stimulative musical elements, which comprise the BMRI-2, result in heightened motivation and enhanced energy that induces physical movement. Further, hearing this song brings me back to 2018 when I attended my first music festival, Defqon.1. As such, I have developed an extramusical association with this song as it reminds me of the electrifying and energetic atmosphere of the festival and further motivates me to push myself harder (Clark, Baker & Taylor, 2016). 7. Wieland, R. (2018). Zombie [Recorded by Ran-D]. On Zombie [MP3]. Zeeland, Amsterdam, Netherlands: Armada Music. To begin my final, yet most gruelling exercise, deadlifts, I have chosen ‘Zombie’ by Ran-D because of its vivace tempo of 156 BPM which results in reduced fatigue and pain. Patania et al. (2020) reported that high tempo music can effectively alleviate the perception of pain and exhaustion by diverting focus away from areas of discomfort. This distracting effect is vital in maintaining the highest degree of performance throughout the remainder of my workout as it 5 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 decreases the RPE of my subsequent sets. Moreover, upbeat tempo music has been shown to produce physiological responses (e.g., the release of endorphins) that inhibit our perception of pain (Ballmann et al., 2019). 8. Davidson, T. & Magid, D. (2018). Overkill [Recorded by RIOT]. On Dogma Resistance [MP3]. Vancouver, Canada: Monstercat. For my final, heaviest sets of deadlifts, I selected ‘Overkill’ by RIOT because of the personal associations developed and reinforced throughout my years of training. These extra-musical associations are driven by the song’s vivace tempo of 174 BPM which make this song extremely motivating and ergogenic (Trehub & Schellenberg, 1995). Similar to a boxer becoming conditioned to a specific piece of music prior to fighting, I have trained my brain to produce a ‘fight-or-flight’ response when hearing this song. As such, I am highly motivated to push my body to its limits and from experience regularly achieve new personal bests under this song’s guidance. However, my experience differs from the findings of Pujol and Langenfeld (1999) who concluded that the ergogenic effects of music are not present at supramaximal exercise intensity. 9. Fogelmark, K. Garritsen, M.G., & Nedler, A. (2018). High on Life [Recorded by Martin Garrix]. On Kontor Festival Sounds 2018.03 – The Closing [MP3]. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Stmpd Rcrds. Commencing my cool down, I opted for ‘High on Life’ by Martin Garrix due to its elated lyrics and exultant melody which combine to yield a euphoric psychological state that motivates me to adhere to my daily workouts. The song’s repetitious post-chorus lyrics “High on life ‘til the day we die” embody and amplify the feeling of ecstasy evoked within myself upon completion of my training session. In addition, I find myself humming along to the unforgettable and joyful melody which results in a concoction of ‘feel good’ neurotransmitters being released. To support, the work of Salimpoor, Benovoy, Larcher, Dagher and Zatorre (2011) found that the melodic features of music are responsible for heightened emotional arousal due to a release of endogenous dopamine. 6 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 10. Gonzalez, A.G., Gonzalez, Y. & Kibby, M. (2011). Midnight City [Recorded by M83]. On Hurry Up, We’re Dreaming [MP3]. Paris, France: Naïve Records. To end my playlist, and training session, I have chosen ‘Midnight City’ by M83 for two distinct reasons. First, due to its ability to maintain a degree of physiological arousal with its medium tempo of 100 BPM, such that I translate my intra-workout alertness to everyday activities. Second, because it creates a perfect ending to my workout with its euphoric melody which yields the psychological benefits of improved mood, reduced stress as well as pride in my physical accomplishments achieved during the training session. However, this choice of end of workout music is in contrast with the findings of Palit and Aysia (2015) who recommend slower tempo music during cool down as it reduces physiological arousal to resting levels. Final Comments Overall, I have had tremendous success in using my music playlist to motivate me to constantly push my limits as well as enhance my athletic performance leading to improved physical health. I accredit the playlist’s success to my strategic ordering and selection of the songs in line with the recommendations of the literature. First, I adopted the motivational lyrics of Eminem to ensure I began the workout motivated to train hard. Next, I selected songs due to both their musical elements as well as non-musical associations which produced the highest motivating and ergogenic qualities in order to combat fatigue, increase work output and lower RPE. To conclude the workout, I chose music which yielded psychological benefits such as improved mood in order to leave the gym in a positive mindset. Despite the multitude of physical as well as mental health benefits of listening to music whilst exercising, the playlist was only tested on myself, thus its peculiar and diverse genre selection, namely, rap, pop, progressive house, drum and bass, hardstyle and electronic dance music, may not be appreciated by all listeners (Schäfer, 2016). Moreover, certain songs were chosen on account of the unique, positive personal associations these songs evoke. However, other listeners may experience opposing associations and memories because of differing environmental backgrounds (Sakka & Saarikallio, 2020). Since preferred music has been shown to produce significant motivating and ergogenic effects, given the uniqueness of every individual, for a playlist to be most effective it should be personalised (Ballmann et al., 2019). Lastly, after testing this playlist over several weeks, I have started to find it repetitive which has personally diminished 7 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 the playlist’s effectiveness in motivating and producing performance enhancing benefits. To combat this, multiple playlists could be created, and cycled between to avoid the predictability and boredom of using a singular playlist. To promote greater community wide participation in physical activity, society should be educated about the potential health benefits of music listening whilst exercising and encouraged to design their own music playlists. By constructing a personal music playlist, individuals can select their favourite genres and artists, preferred volume or tempo, as well as songs with personal associations to realise their exercise goals. 8 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 References Ballmann, C., Maynard, D., Lafoon, Z., Marshall, M., Williams, T., & Rogers, R. (2019). Effects of listening to preferred versus non-preferred music on repeated Wingate Anaerobic Test performance. Sports, 7(8), 185. doi:10.3390/sports7080185 Barrett, F., Grimm, K., Robins, R., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Janata, P. (2010). Musicevoked nostalgia: Affect, memory, and personality. Emotion, 10(3), 390-403. doi:10.1037/a0019006 Beaulieu-Boire, G., Bourque, S., Chagnon, F., Chouinard, L., Gallo-Payet, N., & Lesur, O. (2013). Music and biological stress dampening in mechanically-ventilated patients at the intensive care unit ward—a prospective interventional randomized crossover trial. Journal of Critical Care, 28(4), 442-450. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.01.007 Bishop, D., Karageorghis, C., & Loizou, G. (2007). A grounded theory of young tennis players’ use of music to manipulate emotional state. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(5), 584-607. doi:10.1123/jsep.29.5.584 Clark, I., Baker, F., Peiris, C., Shoebridge, G., & Talor, N. (2016). The Brunel Music Rating Inventory-2 is a reliable and valid instrument for older cardiac rehabilitation patients selecting music for exercise. Psychology of Music, 44(2), 249-262. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/1777478171?accountid=12372 Clark, I., Baker, F., & Taylor, N. (2016). Older adults’ music listening preferences to support physical activity following cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Music Therapy, 53(4), 364397. doi:10.1093/jmt/thw011 Corigliano, B. (2017). What are the ergogenic effects of music during exercise? (Master’s thesis). State University of New York, New York. Gault, B. (2011). Listen to the music! Popular music and active listening. Cleveland: American Orff-Schulwerk Association. Karageorghis, C., Hutchinson, J., Jones, L., Farmer, H., Ayhan, M., & Wilson, R. et al. (2013). Psychological, psychophysical, and ergogenic effects of music in swimming. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(4), 560-568. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.01.009 9 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 Karageorghis, C., & Priest, D. (2012). Music in the exercise domain: A review and synthesis (Part II). International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(1), 67-84. doi:10.1080/1750984x.2011.631027 Karageorghis, C., Priest, D., Terry, P., Chatzisarantis, N., & Lane, A. (2006). Redesign and initial validation of an instrument to assess the motivational qualities of music in exercise: The Brunel Music Rating Inventory-2. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(8), 899909. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2011.631026 Kelley, E., Andrick, G., Benzenbower, F., & Devia, M. (2014). Physiological arousal response to differing musical genres. Modern Psychological Studies, 20(1), 25-36. McCown, W., Keiser, R., Mulhearn, S., & Williamson, D. (1997). The role of personality and gender in preference for exaggerated bass in music. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(4), 543-547. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(97)00085-8 McFerran, K. (2019). Music and Health MUSI20150 Lecture 2 Semester 2 – 2020 [Lecture notes]. Retrieved from https://canvas.lms.unimelb.edu.au/courses/93893/pages/2-dot-2video-2-music-and-physical-activity?module_item_id=1981850 Palit, H., & Aysia, D. (2015). The effect of pop musical tempo during post treadmill exercise recovery time. Procedia Manufacturing, 4, 17-22. Papa, R. R. (1990). The effects of selected types of musical stimuli upon muscular strength and endurance performance of college age athletes. Unpublished master’s thesis, Slippery Rock University, Slippery Rock, PA. Patania, V., Padulo, J., Iuliano, E., Ardigò, L., Čular, D., Miletić, A., & De Giorgio, A. (2020). The psychophysiological effects of different tempo music on endurance versus highintensity performances. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00074 Pujol, T., & Langenfeld, M. (1999). Influence of music on Wingate Anaerobic Test performance. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 88(1), 292-296. doi:10.2466/pms.1999.88.1.292 10 MUSI20150 Karl Hemmings 1085371 Sakka, L., & Saarikallio, S. (2020). Spontaneous music-evoked autobiographical memories in individuals experiencing depression. Music & Science, 3, 1-15. doi:10.1177/2059204320960575 Salimpoor, V., Benovoy, M., Larcher, K., Dagher, A., & Zatorre, R. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 257-262. doi:10.1038/nn.2726 Schäfer, T. (2016). The goals and effects of music listening and their relationship to the strength of music preference. Plos One, 11(3). doi:10.1372/journal.pone.0151634 Szabo, A., Small, A., & Leigh, M. (1999). The effects of slow-and fast-rhythm classical music on progressive cycling to voluntary physical exhaustion. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 39(3), 220-225. Trehub, S., & Nakata, T. (2001). Emotion and music in infancy. Musicae Scientiae, 5(1_suppl), 37-61. doi:10.1177/10298649020050s103 van Dyck, E., Six, J., Soyer, E., Denys, M., Bardijn, I., & Leman, M. (2017). Adopting a musicto-heart rate alignment strategy to measure the impact of music and its tempo on human heart rate. Musicae Scientiae, 21(4), 390-404. doi:10.1177/1029864917700706 11