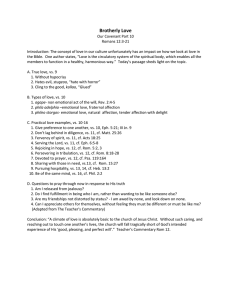

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348485756 Strength training is as effective as stretching for improving range of motion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preprint · January 2021 DOI: 10.31222/osf.io/2tdfm CITATIONS READS 0 2,896 10 authors, including: José Afonso Rodrigo Ramirez-Campillo University of Porto Universidad de Los Lagos 170 PUBLICATIONS 1,577 CITATIONS 382 PUBLICATIONS 4,003 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE João C. Moscão 12 PUBLICATIONS 3 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Tiago Rocha Instituto Politécnico de Leiria 11 PUBLICATIONS 14 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Longitudinal and multidimensional analysis of youth soccer players View project Special Issue "Resistance Exercise for Health, Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Muscle Strength" View project All content following this page was uploaded by José Afonso on 07 May 2021. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 1 Strength training is as effective as stretching for improving range of motion: A systematic 2 review and meta-analysis. 3 4 José Afonso, Ph.D. 1*, Rodrigo Ramirez-Campillo, Ph.D. 2,3, João Moscão4, Tiago Rocha, 5 M.Sc. 5, Rodrigo Zacca, Ph.D. 1,6,7, Alexandre Martins, B.Sc. 1, André A. Milheiro, M.Sc.1, 6 João Ferreira, B.Sc. 8, Hugo Sarmento, Ph.D. 9, Filipe Manuel Clemente, Ph.D. 10,11 7 8 1 9 Rua Dr. Plácido Costa, 91, 4200-450 Porto, Portugal. Centre for Research, Education, Innovation and Intervention in Sport, Faculty of Sport of the University of Porto. 10 2 Department of Physical Activity Sciences. Universidad de Los Lagos. Lord Cochrane 1046, Osorno, Chile. 11 3 Centro de Investigación en Fisiología del Ejercicio. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad Mayor. San Pio X, 2422, 12 Providencia, Santiago, Chile. 13 4 REP Exercise Institute. Rua Manuel Francisco 75-A 2º C 2645-558 Alcabideche, Portugal. 14 5 Polytechnic of Leiria, Rua General Norton de Matos, Apartado 4133, 2411-901 Leiria, Portugal. 15 6 Porto Biomechanics Laboratory (LABIOMEP), University of Porto, Rua Dr. Plácido Costa, 91, 4200-450 Porto, 16 Portugal. 17 7 18 of Brazil, Brasília, Brazil. 19 8 20 Almeida, 431, 4249-015 Porto, Portugal. 21 9 22 10 23 de Nun’Álvares, 4900-347, Viana do Castelo, Portugal. 24 11 Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Educational Personnel Foundation (CAPES), Ministry of Education Superior Institute of Engineering of Porto, Polytechnic Institute of Porto. Rua Dr. António Bernardino de Faculty of Sport Sciences and Physical Education, University of Coimbra, 3040-256, Coimbra, Portugal. Escola Superior Desporto e Lazer, Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo, Rua Escola Industrial e Comercial Instituto de Telecomunicações, Department of Covilhã, 1049-001, Lisboa, Portugal. 25 26 *Corresponding author: José Afonso | jneves@fade.up.pt. 27 28 1 29 30 Summary box 31 What is already known? 32 • 33 Stretching is effective for improving in range of motion (ROM), but promising findings have suggested that strength training also generates ROM gains. 34 35 What are the new findings? 36 • Strength training seems to be as effective as stretching in generating ROM gains. 37 • In contradiction with existing guidelines, stretching is not strictly necessary for improving 38 39 40 ROM, as strength may provide an equally valid alternative. • These findings were consistent across studies, regardless of the characteristics of the population and of the specificities of strength training and stretching programs. 41 42 2 43 44 ABSTRACT 45 Background: Range of motion (ROM) is an important feature of sports performance and 46 health. Stretching is usually prescribed to improve promote ROM gains, but evidence has 47 suggested that strength training (ST) also improves ROM. However, it is unclear if its efficacy 48 is comparable to stretching. Objective: To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of 49 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of ST and stretching on ROM. 50 Protocol: INPLASY: 10.37766/inplasy2020.9.0098. Data sources: Cochrane Library, 51 EBSCO, PubMed, Scielo, Scopus, and Web of Science were consulted in early October 2020, 52 followed by search within reference lists and consultation of four experts. No constraints on 53 language or year. Eligibility criteria (PICOS): (P) humans of any sex, age, health or training 54 status; (I) ST interventions; (C) stretching interventions (O) ROM; (S) supervised RCTs. Data 55 extraction and synthesis: Independently conducted by multiple authors. Quality of evidence 56 assessed using GRADE; risk-of-bias assessed with RoB 2. Results: Eleven articles (n = 452 57 participants) were included. Pooled data showed no differences between ST and stretching on 58 ROM (ES = -0×22; 95% CI = -0×55 to 0×12; p = 0×206). Sub-group analyses based on RoB, 59 active vs. passive ROM, and specific movement-per-joint analyses for hip flexion and knee 60 extension showed no between-protocol differences in ROM gains. Conclusion: ST and 61 stretching were not different in improving ROM, regardless of the diversity of protocols and 62 populations. Barring specific contra-indications, people who do not respond well or do not 63 adhere to stretching protocols can change to ST programs, and vice-versa. 64 65 KEYWORDS: systematic review; meta-analysis; strength training; flexibility; stretching; 66 range of motion. 67 3 68 4 69 70 Introduction 71 Improving range of motion (ROM) is a core goal for the general population,[1] as well 72 as in clinical contexts,[2] such as when treating acute respiratory failure,[3] plexiform 73 neurofibromas,[4] and total hip replacement.[5] Unsurprisingly, ROM gains are also relevant 74 in different sports,[6] such as basketball, baseball and rowing,[7-9] among others. ROM is 75 improved through increased stretch tolerance, augmented fascicle length and changes in 76 pennation angle,[10] as well as reduced tonic reflex activity.[11] Stretching is usually 77 prescribed to increase ROM in sports,[12, 13] clinical settings such as chronic low back 78 pain,[14] rheumatoid arthritis,[15] and exercise performance in general.[16] Stretching 79 techniques include static (active or passive), dynamic, or proprioceptive neuromuscular 80 facilitation (PNF), all of which can improve ROM.[1, 17-20] 81 However, reduced ROM and muscle weakness are deeply associated.[21-23] Therefore, 82 although strength training (ST) primarily addresses muscle weakness through methods such as 83 resistance training or similar protocols, it has been shown to increase ROM in athletic 84 populations,[24, 25] as well as in healthy elderly people[26] and women with chronic 85 nonspecific neck pain.[27] ST focused on concentric and eccentric contractions has been 86 shown to increase fascicle length. [28-30] Better agonist-antagonist co-activation[31], 87 reciprocal inhibition,[32] and adjusted stretch-shortening cycles[33] may also explain why ST 88 is a suitable method for improving ROM. 89 Nevertheless, studies comparing the effects of ST and stretching in ROM have 90 presented conflicting evidence,[34, 35] and many have small sample sizes.[36, 37] Developing 91 a systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) may help summarize this conflicting evidence 92 and increase statistical power, thus providing clearer guidance for interventions.[38] Therefore, 5 93 the aim of this SRMA was to compare the effects of supervised and randomized ST versus 94 stretching protocols on ROM in participants of any health and training status. 95 96 97 METHODS 98 Protocol and registration 99 100 The methods and protocol registration were preregistered prior to conducting the review: INPLASY, no.202090098, DOI: 10.37766/inplasy2020.9.0098. 101 102 Eligibility criteria 103 Articles were eligible for inclusion if published in peer-reviewed journals, with no 104 restrictions in language or publication date. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic 105 Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were adopted.[39] Participants, 106 interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design (P.I.C.O.S.) were established as 107 follows: (i) participants with no restriction regarding health, sex, age, or training status; (ii) ST 108 interventions supervised by a certified professional, using resistance training or similar 109 protocols; (iii) comparators were supervised groups performing any form of stretching (iv) 110 outcomes were ROM assessed in any joint; (v) randomized controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs 111 reduce bias and better balance participant features between the groups,[38] and are important 112 for the advancement of sports science.[40] There were no limitations regarding intervention 113 length. 114 Reviews, letters to editors, trial registrations, proposals for protocols, editorials, book 115 chapters, and conference abstracts were excluded. Exclusion criteria based on P.I.C.O.S.: (i) 116 research with non-human animals; (ii) non-ST protocols or ST interventions combined with 117 other methods (e.g., endurance); unsupervised interventions; (iii) stretching or ST + stretching 6 118 interventions combined with other training methods (e.g., endurance); protocols without 119 stretching; unsupervised interventions; (iv) studies not reporting ROM; (v) non-randomized 120 interventions. 121 122 Information sources and search 123 Six databases were used to search and retrieve the articles in early October 2020: 124 Cochrane Library, EBSCO, PubMed (including MEDLINE), Scielo, Scopus, and Web of 125 Science (Core Collection). Boolean operators were applied to search the article title, abstract 126 and/or keywords: (“strength training” OR “resistance training” OR “weight training” OR 127 “plyometric*” OR “calisthenics”) AND (“flexibility” OR “stretching”) AND “range of 128 motion” AND “random*”. Specificities of each search engine: (i) in Cochrane Library, items 129 were limited to trials, including articles but excluding protocols, reviews, editorials and similar 130 publications; (ii) in EBSCO, the search was limited to articles in scientific, peer-reviewed 131 journals (iii) in PubMed, the search was limited to title or abstract; publications were limited 132 to RCTs and clinical trials, excluding books and documents, meta-analyses, reviews and 133 systematic reviews; (iv) in Scielo, Scopus and Web of Science, the publication type was limited 134 to article; and (v) in Web of Science, “topic” is the term used to refer to title, abstract and 135 keywords. 136 An additional search within the reference lists of the included records was conducted. 137 The list of articles and inclusion criteria were then sent to four experts to suggest additional 138 references. The search strategy and consulted databases were not provided in this process to 139 avoid biasing the experts’ searches. More detailed information is available as supplementary 140 material. 141 142 Search strategy 7 143 Here, we provide the specific example of search conducted in PubMed: 144 ((("strength training"[Title/Abstract] OR "resistance training"[Title/Abstract] OR 145 "weight 146 "calisthenics"[Title/Abstract]) 147 “stretching”[Title/Abstract])) AND (“range of motion”[Title/Abstract])) AND 148 (“random*”[Title/Abstract]). 149 After this search, the filters RCT and Clinical Trial were applied. training"[Title/Abstract] OR "plyometric*"[Title/Abstract] AND (“flexibility”[Title/Abstract] OR OR 150 151 Study selection 152 J.A. and F.M.C. each conducted the initial search and selection stages independently, 153 and then compared result to ensure accuracy. J.F. and T.R. independently reviewed the process 154 to detect potential errors. When necessary, re-analysis was conducted until a consensus was 155 achieved. 156 157 Data collection process 158 J.A., F.M.C., A.A.M. and J.F. extracted data, while J.M., T.R., R.Z. and A.M. 159 independently revised the process. Data for the meta-analysis was extracted by JA and 160 independently verified by A.A.M. and R.R.C. Data is available for sharing. 161 162 Data items 163 Data items: (i) Population: subjects, health status, sex/gender, age, training status, 164 selection of subjects; (ii) Intervention and comparators: study length in weeks, weekly 165 frequency of the sessions, weekly training volume in minutes, session duration in minutes, 166 number of exercises per session, number of sets and repetitions per exercise, load (e.g., % 167 1RM), full vs. partial ROM, supervision ratio; in the comparators, modality of stretching 168 applied was also considered; adherence rates were considered a posteriori; (iii) ROM testing: 8 169 joints and actions, body positions (e.g., standing, supine), mode of testing (i.e., active, passive, 170 both), pre-testing warm-up, timing (e.g., pre- and post-intervention, intermediate assessments), 171 results considered for a given test (e.g., average of three measures), data reliability, number of 172 testers and instructions provided during testing; (iv) Outcomes: changes in ROM for 173 intervention and comparator groups; (vi) funding and conflicts of interest. 174 175 Risk of bias in individual studies 176 Risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias 177 tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).[41] J.A. and A.M. independently completed RoB analysis, 178 which was reviewed by F.M.C. Where inconsistencies emerged, the original articles were re- 179 analyzed until a consensus was achieved. 180 181 Summary measures 182 Meta-analysis was conducted when ≥3 studies were available.[42] Pre- and post- 183 intervention means and standard deviations (SDs) for dependent variables were used after 184 being converted to Hedges’s g effect size (ES).[42] When means and SDs were not available, 185 they were calculated from 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or standard error of mean (SEM), 186 using Cochrane’s RevMan Calculator for Microsoft Excel.[43] When ROM data from different 187 groups (e.g. men and women) or different joints (e.g. knee and ankle) was pooled, weighted 188 formulas were applied.[38] 189 190 Synthesis of results 191 The inverse variance random-effects model for meta-analyses was used to allocate a 192 proportionate weight to trials based on the size of their individual standard errors,[44] and 193 accounting for heterogeneity across studies.[45] The ESs were presented alongside 95% CIs 9 194 and interpreted using the following thresholds:[46] <0×2, trivial; 0×2–0×6, small; >0×6–1×2, 195 moderate; >1×2–2×0, large; >2×0–4×0, very large; >4×0, extremely large. Heterogeneity was 196 assessed using the I2 statistic, with values of <25%, 25-75%, and >75% considered to represent 197 low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively.[47] 198 199 Risk of bias across studies 200 Publication bias was explored using the extended Egger’s test,[48] with p<0×05 201 implying bias. To adjust for publication bias, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the 202 trim and fill method,[49] with L0 as the default estimator for the number of missing studies.[50] 203 204 Moderator analyses 205 Using a random-effects model and independent computed single factor analysis, 206 potential sources of heterogeneity likely to influence the effects of training interventions were 207 selected, including i) ROM type (i.e., passive vs active), ii) studies RoB in randomization and 208 iii) studies RoB in measurement of the outcome.[51] These analyses were decided post- 209 protocol registration. 210 211 All analyses were carried out using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis program 212 (version 2; Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). Statistical significance was set at p≤0×05. Data for 213 the meta-analysis was extracted by JA and independently verified by A.A.M. and R.R.C. 214 215 Quality and confidence in findings 216 Although not planned in the registered protocol, we decided to abide by the Grading of 217 Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE),[52] which addresses 218 five dimensions that can downgrade studies when assessing the quality of evidence in RCTs. 10 219 RoB, inconsistency (through heterogeneity measures), and publication bias were addressed 220 above and were considered a priori. Directness was guaranteed by design, as no surrogates 221 were used for any of the pre-defined P.I.C.O. dimensions. Imprecision was assessed on the 222 basis of 95% CIs. 223 224 225 RESULTS 226 Study selection 227 Initial search returned 194 results (52 in Cochrane Library, 11 in EBSCO, 11 in 228 PubMed, 9 in Scielo, 88 in Scopus, and 23 in Web of Science). After removal of duplicates, 229 121 records remained. Screening the titles and abstracts for eligibility criteria resulted in the 230 exclusion of 106 articles: 26 were not original research articles (e.g., trial registrations, 231 reviews), 24 were out of scope, 48 did not have the required intervention or comparators, five 232 did not assess ROM, two were non-randomized and one was unsupervised. Fifteen articles 233 were eligible for full-text analysis. One article did not have the required intervention,[53] and 234 two did not have the needed comparators.[54, 55] In one article, the ST and stretching groups 235 performed a 20-30 minutes warm-up following an unspecified protocol.[56] In another, the 236 intervention and comparator were unsupervised[57], and in one the stretching group was 237 unsupervised[58]. Finally, in one article, 75% of the training sessions were unsupervised.[59] 238 Therefore, eight articles were included at this stage.[24, 34-37, 60-62] 239 A manual search within the reference lists of the included articles revealed five 240 additional potentially fitting articles. Two lacked the intervention group required[63, 64] and 241 two were non-randomized.[65, 66] One article met the inclusion criteria.[67] Four experts 242 revised the inclusion criteria and the list of articles and suggested eight articles based on their 243 titles and abstracts. Six were excluded: interventions were multicomponent;[68, 69] 11 244 comparators performed no exercise;[70, 71] out of scope;[72] and unsupervised stretching 245 group.[73] Two articles were included,[74, 75] increasing the list to eleven articles,[24, 34-37, 246 60-62, 67, 74, 75] with 452 participants eligible for meta-analysis (Figure 1). 247 248 12 249 Records identified through database search (n = 194) Records after duplicates removed (n = 121) Records excluded (n = 106) Records screened (n = 121) Full-text articles assessed for eligibility (n = 15) Full-text articles excluded, with reasons (n = 7) • 3 articles did not have the required intervention and/or comparators. • 3 had at least one group of interest performing the intervention unsupervised. • 1 had an undisclosed warm-up protocol that was longer than the intervention. Additional records fitting inclusion criteria identified after search within the reference lists of the included articles (n = 1) Studies included in qualitative synthesis (n = 8+1+2 = 11) Additional records fitting inclusion criteria recommended by four external experts from two countries and three different institutions (n = 2) Studies included in quantitative synthesis (n = 11) 250 251 Figure 1. Flowchart describing the study selection process. 252 253 13 254 255 Study characteristics and results 256 The data items can be found in Table 1. The study of Wyon, Smith [62] required 257 consultation of a previous paper[76] to provide essential information. Samples ranged from 258 27[37] to 124 subjects,[34] including: trained participants,[24, 36, 61, 62] healthy sedentary 259 participants,[35, 60, 67] sedentary and trained participants,[75] workers with chronic neck 260 pain,[37] participants with fibromyalgia,[74] and elderly participants with difficulties in at least 261 one of four tasks: transferring, bathing, toileting, and walking.[34] Seven articles included only 262 women[36, 62, 67, 74] or predominantly women,[34, 35, 37] three investigated only men[24, 263 75] or predominantly men,[60] and one article had a balanced mixture of men and women.[61] 264 Interventions lasted between five[60] and 16 weeks[67]. Minimum weekly training frequency 265 was two sessions[37, 74] and maximum was five.[62] Six articles provided insufficient 266 information concerning session duration.[35, 36, 61, 62, 67, 75] Ten articles vaguely defined 267 training load for the ST and stretching groups,[24, 34, 37, 60, 61, 74, 75] or for stretching 268 groups.[35, 36, 67] Six articles did not report on using partial or full ROM during ST 269 exercises.[24, 34, 36, 37, 61, 67] Different stretching modalities were implemented: static 270 active,[35, 37, 60, 67, 74, 75] dynamic,[34, 36] dynamic with a 10-second hold,[24] static 271 active in one group and static passive in another,[62] and a combination of dynamic, static 272 active, and PNF.[61] 273 Hip joint ROM was assessed in seven articles,[24, 34, 36, 60-62, 67] knee ROM in 274 five,[34-36, 60, 75] shoulder ROM in four,[34, 36, 60, 74] elbow and trunk ROM in two,[34, 275 36] and cervical spine[37] and the ankle joint ROM in one article.[34] In one article, active 276 ROM (AROM) was tested for the trunk, while passive ROM (PROM) was tested for the other 277 joints.[34] In one article, PROM was tested for goniometric assessments and AROM for hip 278 flexion.[36] In another, AROM was assessed for the shoulder and PROM for the hip and 14 279 knee.[60] Three articles only assessed PROM[35, 61, 75] and four AROM,[24, 37, 67, 74] 280 while one assessed both for the same joint.[62] 281 282 15 283 Table 1. Characteristics of included randomized trials. Article Population and common Strength training group program features Task-Specific Subjects: 161. n = 81 (60 completed). Resistance Health status: Elderly people Weekly volume (minutes): Training to dependent on help for 180. Improve the performing at least one of four Session duration in Ability of tasks: transferring, minutes: 60. Activities of bathing, toileting and walking. No. exercises per session: Daily Living– Gender: ST: 84% women; 16. Impaired Older STRE: 88% women. No. sets and repetitions: Adults to Rise Age: ST: 82·0±6·4; STRE: 1*7-8 based on maximum from a Bed and 82·4±6·3. target of 9 (bed-rise from a Chair.[34] Training status: Not tasks). 1*5 based on participating in regular maximum target of 6 strenuous exercise. (chair-rise tasks). Selection of subjects: Seven Load: Unclear. Loads congregate housing facilities. were incremented if Length (weeks): 12. subjects were not feeling Weekly sessions: 3. challenged enough. Adherence: average 81% of Full or partial ROM: the sessions. N/A. Funding: National Institute on Supervision ratio: 1:1. Aging (NIA) Claude Pepper Older Adults Independence Center (Grant AG0 8808 and NIA Grant AG10542), the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development, and the AARP-Andrus Foundation. Conflicts of interest: N/A. Stretching versus Subjects: 45 undergraduate n = 15. strength training students. Weekly volume (minutes): in lengthened Health status: 30º knee N/A. position in extension deficit with the hip Session duration in subjects with at 90º when in supine minutes: N/A. tight hamstring position. No injuries in the Comparator group(s)* ROM testing STRE n = 80 (64 completed). Weekly volume (minutes): 180. Session duration in minutes: 60. No. exercises per session: N/A. No. sets and repetitions: N/A. Stretching modality: Dynamic. Load: Low-intensity, but without a specified criterion. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: One supervisor per group, but group size was N/A. Joints and actions: Elbow (extension), shoulder (abduction), hip (flexion and abduction), knee (flexion and extension), ankle (dorsiflexion) and trunk (flexion, extension, lateral flexion). Positions: Supine (elbow, shoulder, hip, knee and ankle); standing (lumbar spine). Mode: Active for trunk, passive for the other joints. Warm-up: N/A. Timing: Baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks. Results considered in the tests: N/A. Data reliability: ICCs of 0·65 to 0·86 for trunk measures. Unreported for other measures. No. testers: N/A. Instructions during testing: N/A. STRE n = 15. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 1. No. sets and repetitions: 4*30’’. Stretching modality: Static. Joints and actions: Knee (extension). Positions: Sitting. Mode: Passive. Warm-up: Yes, but unclear with regard to specifications. 16 Qualitative results for ROM The ST group had significant improvements in all ROM measures, except hip flexion and abduction. The STRE group had no significant change in any of the ROM values. None of the groups experienced significant improvements in ROM. muscles: A randomized controlled trial.[35] Group-based exercise at workplace: shortterm effects of neck and shoulder resistance training in video display unit workers with work-related chronic neck pain – a pilot randomized trial.[37] lower limbs and no lower back pain. Gender: 39 women, 6 men. Age: 21·33±1·76 years (ST); 22·60±1·84 years (STRE). Training status: No participation in ST or STRE programs in the previous year. Selection of subjects: announcements posted at the University. Length (weeks): 8. Weekly sessions: 3. Adherence: N/A. Funding: N/A. Conflicts of interest: N/A. Subjects: 35 video display unit workers, 27 completed the program. Health status: chronic neck pain. Gender: 27 women, 8 men. Age: 43 (41-45) in ST; 42 (38·5-44) in STRE. Training status: N/A. Selection of subjects: intranet form. Length (weeks): 7. Weekly sessions: 2. Adherence: average 85% of the sessions in ST and 86% in STRE. Funding: Under “disclosures”, the authors stated “none”. Conflicts of interest: Under “disclosures”, the authors stated “none”. No. exercises per session: 1. No. sets and repetitions: 3*12. Load: 60% of 1RM. Full or partial ROM: Partial. Supervision ratio: N/A. Load: Unclear. Full or partial ROM: Full. Supervision ratio: N/A. Timing: Baseline, 1-week post-protocol. Results considered in the tests: mean of three measures. Data reliability: High. No. testers: 1 (blinded). Instructions during testing: N/A. n = 14. Weekly volume (minutes): 90. Session duration in minutes: 45. No. exercises per session: 10. No. sets and repetitions: 2-3*8-20. Isometric contractions up to 30’’. Load: free-weights with a maximum of 75% MVC and elastic bands of unspecified load. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: ~1:8. STRE n = 13. Weekly volume (minutes): 90. Session duration in minutes: 45. No. exercises per session: 11. No. sets and repetitions: 10*10’’. Stretching modality: Static. Load: N/A. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: ~1:8. Joints and actions: Cervical spine (flexion, extension, lateral flexion, rotation). Positions: Sitting (flexion, extension, lateral flexion) and supine position (rotation). Mode: Active. Warm-up: N/A. Timing: Baseline, 1-week post-protocol. Results considered in the tests: N/A. Data reliability: N/A. No. testers: 1 (blinded). Instructions during testing: N/A. 17 Significant improvements in both groups for all ROM measurements. No differences between the two groups. A randomized controlled trial of muscle strengthening versus flexibility training in fibromyalgia.[74] Influence of Strength and Flexibility Training, Combined or Isolated, on Strength and Subjects: 68; 56 completed the program. Health status: Diagnosed with fibromyalgia (FM). Gender: Women. Age: 49·2±6·36 years in ST, 46·4±8·56 in STRE. Training status: 87% were sedentary. Not engaged in regular strength training programs. Selection of subjects: FM patients referred to rheumatology practice at a teaching university. Length (weeks): 12. Weekly sessions: 2. Adherence: 85% of the initial participants attended ≥13 of 24 classes. N/A for the 46 women that completed the interventions. Funding: Individual National Research Service Award (#1F31NR07337-01A1) from the National Institutes of Health, a doctoral dissertation grant (#2324938) from the Arthritis Foundation, and funds from the Oregon Fibromyalgia Foundation. Conflicts of interest: N/A. Subjects:28 women. Health status: Presumably healthy. Gender: Women. Age: 46±6·5. Training status: Trained in strength and stretching. n = 28. Weekly volume (minutes): 120. Session duration in minutes: 60. No. exercises per session: Presumably 12. No. sets and repetitions: 1*4-5, progressing to 1*12. Load: Low intensity. Slower concentric contractions with a 4’’ isometric hold in the end, and a faster eccentric contraction. Full or partial ROM: Full. Supervision ratio: Presumably 1:28. STRE n = 28. Weekly volume (minutes): 120. Session duration in minutes: 60. No. exercises per session: Presumably 12. No. sets and repetitions: N/A. Stretching modality: Static. Load: Low intensity. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: Presumably 1:28. Joints and actions: Shoulder (the authors report on internal and external rotation, but the movements used actually required a combination of motions). Positions: Presumably standing. Mode: Active. Warm-up: N/A. Timing: Baseline, 12 weeks. Results considered in the tests: N/A. Data reliability: referral to a previous study, but no values for these data. No. testers: 1. Instructions during testing: Reach as far as possible. Both groups had significant improvements in ROM. No differences between groups. n = 7. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 8. STRE n = 7. Weekly volume (minutes): 240. Session duration in minutes: 60. No. exercises per session: N/A. No. sets and repetitions: 3*30. Stretching modality: Dynamic. Load: Stretch to mild discomfort. Joints and actions: Shoulder (flexion, extension, abduction and horizontal adduction) elbow (flexion), hip (flexion and extension), knee (flexion), and trunk (flexion and extension). None of the groups experienced significant improvements in ROM. 18 Flexibility Gains.[36] Effects of Flexibility and Strength Interventions on Optimal Lengths of Hamstring Muscle-Tendon Units.[61] Selection of subjects: Volunteers that would refrain from exercise outside the intervention. Length (weeks):12. Weekly sessions: 4. Not explicit; 48 sessions over 12 weeks. Adherence: Minimum was 44 of the 48 sessions. Funding: N/A. Conflicts of interest: N/A. No. sets and repetitions: 3*8-12 during the 1st month; 3*6-10RM in the 2nd month; 3*10-15RM in the 3rd month. Load: 6-15RM, depending on the month. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. Subjects: 40 college students. Health status: No history of lower extremity injury in the 2 years prior to the study. Gender: 20 men, 20 women. Age: 18–24 years. Training status: participating in exercise 2–3 times per week. Selection of subjects: college students. Length (weeks): 8. Weekly sessions: 3. Adherence: N/A. n = 20. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A No. exercises per session: 4. No. sets and repetitions: 2-4*8-15. For one exercise, 2*50-60’’. Load: N/A. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. Full or partial ROM: Full. Supervision ratio: N/A. STRE + ST n = 7. Completion of both protocols. Unknown duration. ST + STRE n = 7. Completion of both protocols in reverse order. Unknown duration. STRE n = 20. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 4. No. sets and repetitions: 2*15 for dynamic stretching, 2*40-60’’ for static stretching, 3*50’’ for PNF and 3*40-50’’ for foam roll. Stretching modality: active static, dynamic and PNF. Load: N/A. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. 19 Positions: Supine (shoulder flexion, abduction, horizontal adduction, elbow and hip flexion), prone (shoulder and hip extension, and knee flexion) and upright (trunk flexion and extension) for goniometric evaluations. Sitting for sit-and-reach. Mode: Passive for goniometry. Active for sitand-reach. Warm-up: 5- minute walking on treadmill at mild to moderate intensity and four stretching exercises. Timing: Baseline, 12 weeks. Results considered in the tests: Best of 3 trials. Data reliability: Very high. No. testers: 1. Instructions during testing: N/A. Joints and actions: Hip (flexion). Positions: Supine. Mode: Passive. Warm-up: Six-minute warmup including jogging and jumping. Timing: Baseline, 8 weeks. Results considered in the tests: Mean of three trials. Data reliability: Very high. No. testers: N/A. Instructions during testing: N/A. Men and women in both groups significantly improved ROM. No differences between groups. Resistance training vs. static stretching: Effects on flexibility and strength.[60] Eccentric training and static stretching improve hamstring flexibility of high school men.[75] Funding: Partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 81572212) and the Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities, Beijing Sport University (Grant No.: 2017XS017). Conflicts of interest: N/A. Subjects: 37 college students. Health status: Healthy. Gender: 30 men, 12 women; ratio is unclear in the final sample. Age: 21·91±3·64 years. Training status: Untrained. Selection of subjects: Recruited from Physical Education or Exercise Science Classes. Length (weeks): 5. Weekly sessions: 3. Adherence: N/A. Funding: N/A. Conflicts of interest: N/A. Subjects: 69 high-schoolers. Health status: Healthy, but with a 30º loss of knee extension. Gender: Men. Age: 16·45±0·96 years. Training status: Some sedentary, others involved in exercise programs. n = 12. Weekly volume (minutes): 135-180. Session duration in minutes: 45-60. No. exercises per session: eight in days 1 and 2, four in day 3. No. sets and repetitions: 4 sets of unspecified repetitions. Load: N/A. Full or partial ROM: Full. Supervision ratio: 1:12. STRE n = 12. Weekly volume (minutes): 75-90. Session duration in minutes: 2535. No. exercises per session: 13. No. sets and repetitions: 1*30’’ for most stretches. 3*30’’ for one exercise and 3*20’’ for two. Stretching modality: Static. Load: N/A. Full or partial ROM: Full. Supervision ratio: 1:12. n= 24. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 1. No. sets and repetitions: 6 repetitions with 5’’ STRE n= 21. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 1. No. sets and repetitions: Unknown number of repetitions, each lasting 30’’. Stretching modality: Static. 20 Joints and actions: Hip (flexion, extension), knee (extension) and shoulder (extension). Positions: Supine (knee and hip). Prone (shoulder). Mode: Passive for hip and knee, active for shoulder. Warm-up: 5 minutes of stationary bicycle with minimal resistance. Timing: Baseline, 1-week post-protocol. Results considered in the tests: N/A. Data reliability: N/A. No. testers: 1. Instructions during testing: Technical instructions specific to each test. Joints and actions: Knee (extension). Positions: Supine. Mode: Passive. Warm-up: No warm-up. Timing: Baseline, 6 weeks. Results considered in the tests: Two measures for previous reliability Both groups had significant improvements in knee extension, hip flexion and hip extension, but not shoulder extension. No differences between the interventions. Both groups improved ROM. No differences between the interventions. Effects of flexibility combined with plyometric exercises vs. isolated plyometric or flexibility mode in adolescent men hurdlers.[24] Selection of subjects: Volunteers with tight hamstrings. Length (weeks): 6. Weekly sessions: 3 for STRE. N/A for ST. Adherence: N/A for ST. STRE: subjects missing >4 sessions were excluded. Funding: N/A. Conflicts of interest: N/A. Subjects: 34 trained hurdlers. Health status: No lower extremity injury in the previous 30 days. Gender: Men. Age: 15±0·7 years. Training status: ≥3 years of experience in hurdle racing. Selection of subjects: Recruited from three athletic teams. Length (weeks): 12. Weekly sessions: 4. Adherence: N/A. Funding: No funding. Conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest. isometric hold between each. Load: N/A. Full or partial ROM: Full. Supervision ratio: Description suggests a 1:1 ratio. Load: Stretch until a gentle stretch was felt on the posterior thigh. Full or partial ROM: Full. Supervision ratio: Description suggests a 1:1 ratio. calculations, but unclear for the groups’ evaluation. Data reliability: Very high. No. testers: 2 (1 blinded). Instructions during testing: N/A. n= 9. Weekly volume (minutes): 320. Session duration in minutes: 80. No. exercises per session: 4. No. sets and repetitions: 3*30’’. Load: Evolved from low to hard intensity, but no criteria were provided. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. STRE n = 8. Weekly volume (minutes): 320. Session duration in minutes: 80. No. exercises per session: 7. No. sets and repetitions: 5*10’’. Stretching modality: Dynamic with 10’’ static hold. Load: Evolved from low to hard intensity, but no criteria were provided. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. Joints and actions: Hip (flexion and extension). Positions: Supine. Mode: Active. Warm-up: N/A. Timing: Baseline, 12 weeks. Results considered in the tests: Best of 3 attempts. Data reliability: Referral to a previous study, but no values for these data. No. testers: 2. Instructions during testing: N/A. STRE+ ST n = 9. Weekly volume (minutes): 320. Session duration in minutes: 80. No. exercises per session: 11 (4 plyometric; 7 flexibility). No. sets and repetitions: 3*30’’ for plyometrics, 5*10’’ for stretching. Stretching modality: Dynamic with 10’’ static hold. Load: Evolved from low to hard intensity, but no criteria were provided. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. 21 All interventions had significant improvements in ROM. No differences between the interventions. The influence of strength, flexibility, and simultaneous training on flexibility and strength gains.[67] A comparison of strength and stretch interventions on active and passive ranges of movement in dancers: a randomized control trial.[62] Subjects: 80 women. Health status: Healthy. Gender: Women. Age: 35±2·0 (ST), 34±1·2 (STRE), 35±1·8 (ST + STRE), 34±2·1 (nonexercise). Training status: Sedentary. Selection of subjects: Volunteers that were sedentary ≥12 months. Length (weeks): 16. Weekly sessions: 3. Adherence: Minimum was 46 of the 48 sessions. Funding: N/A. Conflicts of interest: N/A. Subjects: 39 dance students, 35 completed. Health status: N/A. Gender: Women (39). Age: 17±0·49 years (ST group); 17±0·56 years (lowintensity STRE); 17±0·56 years (moderate to high intensity STRE). Training status: Moderately trained dance students. Selection of subjects: Recruited from dance college. Length (weeks): 6. Weekly sessions: 5. Adherence: N/A. Funding: N/A. Conflicts of interest: N/A. n = 20. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 8. No. sets and repetitions: 3*8-12 in the 1st and 4th months; 3*6-10 in 2nd month; 3*10-15 in 3rd month. Load: 8-12RM (1st and 4th months); 6-10RM (2nd month); 10-15RM (3rd month). Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. n = 11. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 1. No. sets and repetitions: 3*5, increasing to 3*10 during the program. Each repetition included a 3’’ isometric hold. Load: Unclear, but using body weight. Full or partial ROM: Partial (final 10º). Supervision ratio: N/A. STRE n = 20. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: N/A. No. sets and repetitions: 4*1560’’. Duration of each set started at 15’’ and progressed to 60’’ during the intervention. Stretching modality: Static. Load: Performed at the point of mild discomfort. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. ST + STRE n = 20. STRE protocol followed by the ST protocol. Low-intensity STRE n = 13. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 5. No. sets and repetitions: N/A, but 1’ for each stretch. Stretching modality: Active static. Load: 3/10 perceived exertion. Full or partial ROM: N/A. Supervision ratio: N/A. Moderate-intensity or highintensity STRE n = 11. Weekly volume (minutes): N/A. Session duration in minutes: N/A. No. exercises per session: 5. No. sets and repetitions: N/A. Stretching modality: Passive. Load: 8/10 perceived exertion. Full or partial ROM: N/A. 22 Joints and actions: Hip (flexion) and knee (extension) combined. Positions: Sitting. Mode: Active. Warm-up: 4 stretching exercises (2*10’’). Timing: Baseline, 16 weeks. Results considered in the tests: Maximum of 3 attempts. Data reliability: Very high. No. testers: 1. Instructions during testing: N/A. The interventions significantly improved ROM. Joints and actions: Hip (flexion). Positions: Standing. Mode: Active and passive. Warm-up: 10 minutes of cardiovascular exercise and lower limb stretches. Timing: Baseline, 6 weeks. Results considered in the tests: N/A. Data reliability: N/A. No. testers: N/A. Instructions during testing: Positioning cues for ensuring proper posture. The three groups significantly improved passive ROM, without differences between the groups. No differences between the interventions. The moderate-tohigh intensity STRE group did not improve in active ROM. The two other interventions did. 284 285 286 Supervision ratio: N/A. Legend: N/A – Information not available. ST – Strength training. STRE - Stretching. ROM – Range of motion. MVC – Maximum voluntary contraction. PNF – Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. * Non-exercise groups are not considered in this column. 287 23 288 289 290 In seven articles,[24, 37, 60, 61, 67, 74] ST and stretching groups significantly 291 improved ROM, and the differences between the groups were non-significant. In one article, 292 the ST group had significant improvements in 8 of 10 ROM measures, while dynamic 293 stretching did not lead to improvement in any of the groups.[34] In another article, the three 294 groups significantly improved PROM, without between-group differences; the ST and the 295 static active stretching groups also significantly improved AROM.[62] In two articles, none of 296 the groups improved ROM.[35, 36] 297 298 Risk of bias within studies 299 Table 2 presents assessments of RoB. Bias arising from the randomization process was 300 low in four articles,[34, 36, 62, 74] moderate in one,[37] and high in six.[24, 35, 60, 61, 67, 301 75] Bias due to deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, and selection of 302 the reported results was low. Bias in measurement of the outcome was low in six articles,[35- 303 37, 67, 74, 75] but high in five.[24, 34, 60-62] 304 305 24 306 307 Table 2. Assessments of risk of bias. Cochrane’s RoB 2 1.1.Was the allocation sequence random? 1.2.Was the allocation sequence concealed until participants were enrolled and assigned to interventions ? 1.3.Did baseline differences between groups suggest a problem with the randomizatio n process? 1.4.RoB judgement Leite, De Morton, Souza Li, Garrett Nelson and Whitehead Teixeira [61] Bandy [75] [60] [36] 1.Bias arising from the randomization process Alexander , Galecki [34] Aquino, Fonseca [35] Caputo, Di Bari [37] Jones, Burckhard t [74] Racil, Jlid [24] Simão, Lemos [67] Wyon, Smith [62] Yes. No information . Yes. Yes. No information . No information . No information . No information. No information . No information . Yes. Yes. Probably no. Yes. Yes. Yes. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Yes. No. No information . Yes. No. No. No. Probably no. No. No. No. No. Low risk. High risk. Some concerns . Low risk. Low risk. High risk. High risk. High risk. High risk. High risk. Low risk. 2.Bias due to deviations from intended interventions 25 (effect of assignment to intervention) 2.1.Were participants aware of their assigned intervention during the trial? 2.2.Were carers and people delivering the interventions aware of participants’ assigned intervention during the trial? 2.3.If Y/PY/NI to 2.1 or 2.2: Were there deviations from the intended intervention because of the trial context? 2.4.If Y/PY to 2.3: Were these deviations likely to have affected the outcome? Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probabl y no. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. 26 2.5.If Y/PY/NI to 2.4: Were these deviations from the intended intervention balanced between groups? 2.6.Was an appropriate analysis used to estimate the effect of assignment to intervention? 2.7.If N/PN/NI to 2.6: Was there potential for a substantial impact (on the result) of the failure to analyze participants in the group to which they were randomized)? 2.8.RoB judgement N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probabl y yes. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. 3.Bias due to missing outcome data 3.1.Were data for this Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. 27 Yes. outcome available for all, or nearly all, participants randomized? 3.2.If N/PN/NI to 3.1.: Is there evidence that the result was not biased by missing outcome data? 3.3.If N/PN to 3.2: Could missingness in the outcome depend on its true value? 3.4.If Y/PY/NI to 3.3: Is it likely that missingness in the outcome depended on its true value? 3.5.RoB judgement N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. No. No. No. No. 4. Bias in measurement of the outcome 4.1.Was the method of measuring the outcome No. No. No. No. No. No. 28 No. inappropriate ? 4.2.Could measurement or ascertainment of the outcome have differed between intervention groups? 4.3.If N/PN/NI to 4.1. and 4.2: Were outcome assessors aware of the intervention received by study participants? 4.4.If Y/PY/NI to 4.3: Could assessment of the outcome have been influenced by knowledge of intervention received? 4.5.If Y/PY/NI to 4.4: Is it likely that assessment of Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probabl y no. Probably yes. No. No. No. No. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. Probably yes. No. Probabl y yes. Probably yes. Probably no [blinded goniometer] . Probably yes. N/A. Probabl y yes. Probably yes. N/A. Probably yes. N/A. Probabl y yes. Probably yes. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. Probably yes. Probably yes. N/A. N/A. N/A. N/A. Probably yes. 29 the outcome was influenced by knowledge of intervention received? 4.6.RoB judgement High risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. High risk. High risk. Low risk. High risk. Low risk. High risk. 5.Bias in selection of the reported results 5.1.Were the data that produced this result analyzed in accordance with a prespecified analysis plan that was finalized before unblinded outcome data were available for analysis? 5.2.Is the numerical result being assessed likely to have been selected, on the basis of the results, from multiple eligible outcome measurement Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probabl y no. 30 s (e.g., scales, definitions, time points) within the outcome domain? 5.3.Is the numerical result being assessed likely to have been selected, on the basis of the results, from multiple eligible analyses of the data? RoB judgement Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probably no. Probabl y no. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. Low risk. 308 309 31 310 311 312 Synthesis of results 313 Comparisons were performed between ST and stretching groups, involving eleven 314 articles and 452 participants. Global effects on ROM were achieved pooling data from the 315 different joints. One article did not have the data required,[35] but the authors kindly supplied 316 it upon request. For another article,[36] we also requested data relative to the goniometric 317 evaluations, but obtained no response. Therefore, only data from the sit-and-reach test was 318 used. For one article,[37] means and SDs were obtained from 95% CIs, while in another SDs 319 were extracted from SEMs,[74] using Cochrane’s RevMan Calculator. 320 Of the five articles including both genders, four provided pooled data, with no 321 distinction between genders.[34, 35, 37, 60] One article presented data separated by gender, 322 without significant differences between men and women in response to interventions.[61] 323 Weighted formulas were applied sequentially for combining means and SDs of groups within 324 the same study.[38] Two studies presented the results separated by left and right lower limbs, 325 with both showing similar responses to the interventions;[24, 62] outcomes were combined 326 using the same weighted formulas for the means and SDs. Five articles only presented one 327 decimal place,[24, 34, 37, 61, 67] and so all values were rounded for uniformity. 328 Effects of ST versus stretching on ROM: no significant difference was noted between 329 ST and stretching (ES = -0×22; 95% CI = -0×55 to 0×12; p = 0×206; I2 = 65×4%; Egger’s test p = 330 0×563; Figure 2). The relative weight of each study in the analysis ranged from 6×4% to 12×7% 331 (the size of the plotted squares in Figure 2 reflects the statistical weight of each study). 332 333 32 334 Study name Hedges's g and 95% CI Stretching (n) Alexander et al. (2001) Aquino et al. (2010) Caputo et al. (2017) Jones et al. (2002) Leite et al. (2015) Li et al. (2020) Morton et al. (2011) Nelson & Bandy (2004) Racil et al. (2020) Simão et al. (2011) Wyon et al. (2013) Strength (n) Hedges's g 0.045 0.087 0.220 -0.282 -0.229 -0.616 0.123 -0.101 -0.000 -1.922 0.247 -0.215 -3.00 -1.50 Favours stretching 335 0.00 1.50 3.00 Favours strength 336 Figure 2. Forest plot of changes in ROM after participating in stretching-based compared to strength-based 337 training interventions. Values shown are effect sizes (Hedges’s g) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The size 338 of the plotted squares reflects the statistical weight of the study. 339 340 Additional analysis 341 Effects of ST versus stretching on ROM, moderated by study RoB in randomization: No 342 significant sub-group differences in ROM changes (p = 0·256) was found when programs with 343 high RoB (6 studies; ES = -0·41; 95% CI = -1·02 to 0·20; within-group I2 = 77·5%) were 344 compared to programs with low RoB (4 studies; ES = -0·03; 95% CI = -0·29 to 0·23; within- 345 group I2 = 0·0%) (Supplementary figure 1). 346 Effects of ST versus stretching on ROM, moderated by study RoB in measurement of 347 the outcome: No significant sub-group difference in ROM changes (p = 0·320) was found 348 when programs with high RoB (5 studies; ES = -0·04; 95% CI = -0·31 to 0·24; within-group 349 I2 = 8·0%) were compared to programs with low RoB (6 studies; ES = -0·37; 95% CI = -0·95 350 to 0·22; within-group I2 = 77·3%) (Supplementary figure 2). 351 Effects of ST versus stretching on ROM, moderated by ROM type (active vs. passive): 352 No significant sub-group difference in ROM changes (p = 0·642) was found after training 33 353 programs that assessed active (8 groups; ES = -0·15; 95% CI = -0·65 to 0·36; within-group I2 354 = 78·7%) compared to passive ROM (6 groups; ES = -0·01; 95% CI = -0·27 to 0·24; within- 355 group I2 = 15·3%) (Supplementary figure 3). 356 Effects of ST versus stretching on hip flexion ROM: Seven studies provided data for hip 357 flexion ROM (pooled n = 294). There was no significant difference between ST and stretching 358 interventions (ES = -0·24; 95% CI = -0·82 to 0·34; p = 0·414; I2 = 80·5%; Egger’s test p = 359 0·626; Supplementary figure 4). The relative weight of each study in the analysis ranged from 360 12·0% to 17·4% (the size of the plotted squares in Figure 6 reflects the statistical weight of 361 each study). 362 Effects of ST versus stretching on hip flexion ROM, moderated by study RoB in 363 randomization: No significant sub-group difference in hip flexion ROM changes (p = 0·311) 364 was found when programs with high RoB in randomization (4 studies; ES = -0·46; 95% CI = 365 -1·51 to 0·58; within-group I2 = 86·9%) were compared to programs with low RoB in 366 randomization (3 studies; ES = 0·10; 95% CI = -0·20 to 0·40; within-group I2 = 0·0%) 367 (Supplementary figure 5). 368 Effects of ST versus stretching on hip flexion ROM, moderated by ROM type (active vs. 369 passive): No significant sub-group difference in hip flexion ROM changes (p = 0·466) was 370 found after the programs assessed active (4 groups; ES = -0·38; 95% CI = -1·53 to 0·76; within- 371 group I2 = 87·1%) compared to passive ROM (4 groups; ES = 0·08; 95% CI = -0·37 to 0·52; 372 within-group I2 = 56·5%) (Supplementary figure 6). 373 Effects of ST versus stretching on knee extension ROM: Four studies provided data for 374 knee extension ROM (pooled n = 223). There was no significant difference between ST and 375 stretching interventions (ES = 0·25; 95% CI = -0·02 to 0·51; p = 0·066; I2 = 0·0%; Egger’s test 376 p = 0·021; Supplementary figure 7). After the application of the trim and fill method, the 377 adjusted values changed to ES = 0·33 (95% CI = 0·10 to 0·57), favoring ST. The relative 34 378 weight of each study in the analysis ranged from 11·3% to 54·2% (the size of the plotted 379 squares in Supplementary figure 7 reflects the statistical weight of each study). 380 One article behaved as an outlier in all comparisons (favoring stretching),[67] but after 381 sensitivity analysis the results remained unchanged (p>0·05), with all ST vs. stretching 382 comparisons remaining non-significant. 383 384 Confidence in cumulative evidence 385 Table 3 presents GRADE assessments. ROM is a continuous variable, and so a high 386 degree of heterogeneity was expected.[77] Imprecision was moderate, likely reflecting the fact 387 that ROM is a continuous variable. Overall, both ST and stretching consistently promoted 388 ROM gains, but no recommendation could be made favoring one protocol. 389 390 35 391 392 Table 3. GRADE assessment for the certainty of evidence. Outcome Study RoB1 Publication design bias ROM 393 394 11 RCTs, 452 participants in metaanalysis. Randomization – low in four articles, moderate in one, and high in six. Deviations from intended interventions – Low. Missing outcome data – Low. Measurement of the outcome – low in six articles and high in five. Selection of the reported results – Low. No publication bias. Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision 9 RCTs showed improvements in ROM in both groups. 2 RCTs showed no changes in ROM in either group. 11 RCTs showed effects of equal magnitude for ST and stretching.2 No serious indirectness. Moderate.3 Quality of evidence Moderate. ⨁⨁⨁ Recommendation Strong recommendation for either strength training or stretching4. No recommendation for choosing one of the protocols over the other, as their efficacy in ROM gains was statistically not different. 1 - Meta-analyses moderated by RoB showed no differences between studies with low and high risk. 2 - Because ROM is a continuous variable, high heterogeneity was expected. However, this heterogeneity is mostly between small and large beneficial effects. No adverse effects were reported. 3 - Expected because ROM is a continuous variable. Furthermore, imprecision referred to small to large beneficial effects. 4 – Both strength training and stretching presented benefits without reported adverse effects. Legend: ROM – Range of motion. RCTs: randomized controlled trials. RoB: risk of bias. 395 36 396 397 DISCUSSION 398 Summary of evidence 399 The aim of this SRMA was to compare the effects of supervised and randomized ST 400 compared to stretching protocols on ROM, in participants of any health and training status. 401 Qualitative synthesis showed that ST and stretching interventions were not statistically 402 different in improving ROM, regardless of the nature of the interventions and moderator 403 variables such as gender, health, or training status. Meta-analysis including 11 articles and 452 404 participants showed that ST and stretching interventions were not statistically different in 405 active and passive ROM changes, regardless of RoB in the randomization process, or in 406 measurement of the outcome. RoB was low for deviations from intended interventions, missing 407 outcome data, and selection of the reported results. No publication bias was detected. 408 High heterogeneity is expected in continuous variables,[77] such as ROM. However, 409 more research should be conducted to afford sub-group analysis according to characteristics of 410 the analyzed population, as well as protocol features. For example, insufficient reporting of 411 training volume and intensity meant it was impossible to establish effective dose-response 412 relationships, although a minimum of 5 weeks of intervention,[60] and two weekly sessions 413 were sufficient to improve ROM.[37, 74] Studies were not always clear with regard to the 414 intensity used in ST and stretching protocols. Assessment of stretching intensity is complex, 415 but a practical solution may be to apply scales of perceived exertion,[62] or the Stretching 416 Intensity Scale.[78] ST intensity may also moderate effects on ROM,[79] and ST with full vs 417 partial ROM may have distinct neuromuscular effects[70] and changes in fascicle length.[28] 418 Again, information was insufficient to discuss these factors, which could potentially explain 419 part of the heterogeneity of results. 37 420 Most studies showed ROM gains in ST and stretching interventions, although in two 421 studies neither group showed improvements.[35, 36] Though adherence rates were unreported 422 by Aquino, Fonseca [35], they were above 91.7% in Leite, De Souza Teixeira [36], thus 423 providing an unlikely explanation for these results. In the study of Aquino, Fonseca [35], the 424 participants increased their stretch tolerance, and the ST group changed the peak torque angle, 425 despite no ROM gains. The authors acknowledged that there was high variability in 426 measurement conditions (e.g., room temperature), which could have interfered with 427 calculations. Leite, De Souza Teixeira [36] suggested that the use of dynamic instead of static 428 stretching could explain the lack of ROM gains in the stretching and stretching + ST groups. 429 However, other studies using dynamic stretching have shown ROM gains.[24, 34] 430 Furthermore, Leite, De Souza Teixeira [36] provided no interpretation for the lack of ROM 431 gains in the ST group. 432 Globally, however, both ST and stretching were effective to improve ROM. Why would 433 ST improve ROM in a manner that is not statistically distinguishable from stretching? ST with 434 an eccentric focus demands the muscles to produce force on elongated positions, and a meta- 435 analysis showed limited to moderate evidence that eccentric ST is associated with increases in 436 fascicle length.[80] Likewise, a recent study showed that 12 sessions of eccentric ST increased 437 fascicle length of the biceps femoris long head.[29] However, ST with an emphasis in 438 concentric training has been shown to increase fascicle length when full ROM was 439 required.[28] In a study with nine older adults, ST increased fascicle length in both the eccentric 440 and concentric groups, albeit more prominently in the former.[81] Conversely, changes in 441 pennation angle were superior in the concentric group (35% increase versus 5% increase). 442 Plyometric training can also increase plantar flexor tendon extensibility.[33] 443 One article showed significant reductions in pain associated with increases in 444 strength.[37] Thus, decreased pain sensitivity may be another mechanism through which ST 38 445 promotes ROM gains. An improved agonist-antagonist coactivation is another possible 446 mechanism promoting ROM gains, through better adjusted force ratios.[31, 62] Also, some 447 articles included in the meta-analysis assessed other outcomes in addition to ROM, and these 448 indicated that ST programs may have additional advantages when compared to stretching, such 449 as greater improvements in neck flexors endurance,[37] ten repetition maximum Bench Press 450 and Leg Press,[36, 67] and countermovement jump and 60-m sprint with hurdles,[24] which 451 may favor the choice of ST over stretching interventions. 452 453 454 Limitations 455 After protocol registration, we chose to improve upon the design, namely adding two 456 dimensions (directness and imprecision) that would provide a complete GRADE assessment. 457 Furthermore, subgroup analyses were not planned a priori. There is a risk of multiple subgroup 458 analyses generating a false statistical difference, merely to the number of analyses 459 conducted.[38] However, all analyses showed an absence of significant differences and 460 therefore provide a more complete understanding that the effects of ST or stretching on ROM 461 are consistent across conditions. Looking backwards, perhaps removing the filters used in the 462 initial searches could have provided a greater number of records. Notwithstanding, it would 463 also likely provide a huge number of non-relevant records, including opinion papers and 464 reviews. Moreover, consultation with four independent experts may hopefully have resolved 465 this shortcoming. 466 Due to the heterogeneity of populations analysed, sub-group analysis according to sex 467 or age group were not possible, and so it would be important to explore if these features interact 468 with the protocols in meaningful ways. And there was a predominance of studies with women, 469 meaning more research with men is advised. There was also a predominance of assessments of 39 470 hip joint ROM, followed by knee and shoulder, with the remaining joints receiving little to no 471 attention. In addition, dose-response relationships could not be addressed, mainly due to poor 472 reporting. 473 474 CONCLUSIONS 475 Overall, ST and stretching were not statistically different in ROM improvements, both 476 in short-term interventions[60] and in longer-term protocols,[67] suggesting that a combination 477 of neural and mechanical factors is at play. Therefore, if ROM gains are a desirable outcome, 478 both ST and stretching can be prescribed, in the absence of specific contraindications, 479 especially because studies did not report any adverse effects. People that do not respond well 480 or do not adhere to stretching protocols can change to ST programs, and vice-versa. 481 Furthermore, session duration may negatively impact adherence to an exercise program.[82] 482 Since ST generates ROM gains similar to those obtained with stretching, clinicians may 483 prescribe smaller, more time-effective programs when deemed convenient and appropriate, 484 thus eventually increasing patient adherence rates. 485 486 40 487 488 489 Declaration of interests: J.M. owns a company focused on Personal Trainer’s education but 490 made no attempt to bias the team in protocol design and search process and had no role in 491 extracting data for meta-analyses. The multiple cross-checks described in the methods 492 provided objectivity to data extraction and analysis. Additionally, J.M. had no financial 493 involvement in this manuscript. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare. 494 495 Funding: No funding was used for conducting this meta-analysis. 496 497 41 498 499 Author’s contributions (following ICMJE recommendations) Authors José Afonso Rodrigo RamirezCampillo João Moscão Tiago Rocha Rodrigo Zacca Alexandre Martins André A. Milheiro João Ferreira Hugo Sarmento Filipe Manuel Clemente Acknowledgements Richard Inman Pedro Morouço Daniel MoreiraGonçalves, Fábio Yuzo Nakamura plus two experts who wished to remain anonymous. Substantial contributions to the conceptualization or design of the study; OR the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data √ √ Drafting the manuscript; OR revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content Final approval of the version to be published √ √ √ √ Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work, and to ensure that issues related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ Role Language editing and proof reading. Thorough pre-submission scientific review of the manuscript. Signed consent form below. Review of inclusion criteria and included articles, and proposal of additional articles to be included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Signed consent forms below. 500 501 42 502 503 REFERENCES 504 1. 505 Kluwer; 2018. 506 2. 507 effectiveness of physical exercise interventions for chronic non-specific neck pain: a 508 systematic review with network meta-analysis of 40 randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports 509 Med. 2020 Nov 2. 510 3. 511 Rehabilitation and Hospital Length of Stay Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure: 512 A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2016 Jun 28;315(24):2694-702. 513 4. 514 Selumetinib in Children with Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 515 9;382(15):1430-42. 516 5. 517 replacement. Lancet. 2007 Oct 27;370(9597):1508-19. 518 6. 519 shoulder range of motion screening and in-season risk of shoulder and elbow injuries in 520 overhead athletes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020 521 Sep;54(17):1019-27. 522 7. 523 basketball match-play on ankle dorsiflexion range of motion and vertical jump performance in 524 semi-professional players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2020 Jan;60(1):110-8. 525 8. 526 of Motion and Strength in Baseball Athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2020 Aug 26. ACSM. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (10th Ed.): Wolters de Zoete RM, Armfield NR, McAuley JH, Chen K, Sterling M. Comparative Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC, Thompson JC, Hauser J, Flores L, et al. Standardized Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, et al. Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip Pozzi F, Plummer HA, Shanley E, Thigpen CA, Bauer C, Wilson ML, et al. Preseason Moreno-Pérez V, Del Coso J, Raya-González J, Nakamura FY, Castillo D. Effects of Downs J, Wasserberger K, Oliver GD. Influence of a Pre-throwing Protocol on Range 43 527 9. 528 rowing displayed by Olympic athletes. Sports Biomech. 2020 Jul 17:1-13. 529 10. 530 Range of motion, neuromechanical, and architectural adaptations to plantar flexor stretch 531 training in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2014;117(5):452-62. 532 11. 533 properties of the human plantar-flexor muscles. Muscle Nerve. 2004 Feb;29(2):248-55. 534 12. 535 Stretch Training on Gymnasts Flexibility and Performance. Int J Sports Med. 2019 536 Nov;40(12):779-88. 537 13. 538 impairments following prolonged static stretching without a comprehensive warm-up. Eur J 539 Appl Physiol. 2020 Nov 11. 540 14. 541 transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and exercise for chronic low back pain. N 542 Engl J Med. 1990 Jun 7;322(23):1627-34. 543 15. 544 to improve function of the rheumatoid hand (SARAH): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 545 2015 Jan 31;385(9966):421-9. 546 16. 547 improves exercise performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(10):1825-31. 548 17. 549 Stretching Intensity Does Not Influence Acute Range of Motion, Passive Torque, and Muscle 550 Architecture. J Sport Rehabil. 2020;29(1):1-6. Li Y, Koldenhoven RM, Jiwan NC, Zhan J, Liu T. Trunk and shoulder kinematics of Blazevich A, Cannavan D, Waugh CM, Miller SC, Thorlund JB, Aagaard P, et al. Guissard N, Duchateau J. Effect of static stretch training on neural and mechanical Lima CD, Brown LE, Li Y, Herat N, Behm D. Periodized versus Non-periodized Behm DG, Kay AD, Trajano GS, Blazevich AJ. Mechanisms underlying performance Deyo RA, Walsh NE, Martin DC, Schoenfeld LS, Ramamurthy S. A controlled trial of Lamb SE, Williamson EM, Heine PJ, Adams J, Dosanjh S, Dritsaki M, et al. Exercises Kokkonen J, Nelson AG, Eldredge C, Winchester JB. Chronic static stretching Santos C, Beltrão NB, Pirauá ALT, Durigan JLQ, Behm D, de Araújo RC. Static 44 551 18. 552 stretching has sustained effects on range of motion and passive stiffness of the hamstring 553 muscles. J Sports Sci Med. 2019;18(1):13-20. 554 19. 555 Stretching on Increasing Hip-Flexion Range of Motion. J Sport Rehabil. 2018;27(3):289-94. 556 20. 557 stretching on passive knee-extension range of motion. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation. 558 2005;14(2):95-107. 559 21. 560 muscle weakness and reduced joint range of motion in patients with femoroacetabular 561 impingement syndrome: a case-control study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2020 Jan-Feb;24(1):39-45. 562 22. 563 E, et al. Muscle endurance, strength, and active range of motion in patients with different 564 subphenotypes in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional cohort study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2019 565 2019/03/04;48(2):141-8. 566 23. 567 knee osteoarthritis and knee cartilage injury in sports. Br J Sports Med. 2011 Apr;45(4):304-9. 568 24. 569 combined with plyometric exercises vs. isolated plyometric or flexibility mode in adolescent 570 male hurdlers. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2020;60(1):45-52. 571 25. 572 Effects of different resistance training exercise orders on flexibility in elite judo athletes. 573 Journal of Human Kinetics. 2014;40(1):129-37. Iwata M, Yamamoto A, Matsuo S, Hatano G, Miyazaki M, Fukaya T, et al. Dynamic Lempke L, Wilkinson R, Murray C, Stanek J. The Effectiveness of PNF Versus Static Ford GS, Mazzone MA, Taylor K. The effect of 4 different durations of static hamstring Frasson VB, Vaz MA, Morales AB, Torresan A, Telöken MA, Gusmão PDF, et al. Hip Pettersson H, Boström C, Bringby F, Walle-Hansen R, Jacobsson LTH, Svenungsson Takeda H, Nakagawa T, Nakamura K, Engebretsen L. Prevention and management of Racil G, Jlid MC, Bouzid MS, Sioud R, Khalifa R, Amri M, et al. Effects of flexibility Saraiva AR, Reis VM, Costa PB, Bentes CM, Costae Silva GV, Novaes JS. Chronic 45 574 26. 575 al. Effects of different resistance training frequencies on flexibility in older women. Clin Interv 576 Aging. 2015;10:531-8. 577 27. 578 neck muscle training in the treatment of chronic neck pain in women: a randomized controlled 579 trial. Jama. 2003 May 21;289(19):2509-16. 580 28. 581 range of motion vs. equalized partial range of motion training on muscle architecture and 582 mechanical properties. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018 Sep;118(9):1969-83. 583 29. 584 muscle length on architectural and functional characteristics of the hamstrings. Scand J Med 585 Sci Sports. 2020 Jul 24. 586 30. 587 Impact of the Nordic hamstring and hip extension exercises on hamstring architecture and 588 morphology: implications for injury prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Mar;51(5):469-77. 589 31. 590 muscles' coactivation in response to strength training in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci 591 Med Sci. 2007 Sep;62(9):1022-7. 592 32. 593 al. Resistance training with instability is more effective than resistance training in improving 594 spinal inhibitory mechanisms in Parkinson's disease. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2017 Jan 595 1;122(1):1-10. 596 33. 597 muscle and tendon stiffness in vivo. Physiol Rep. 2017 Aug;5(15). Carneiro NH, Ribeiro AS, Nascimento MA, Gobbo LA, Schoenfeld BJ, Achour A, et Ylinen J, Takala EP, Nykänen M, Häkkinen A, Mälkiä E, Pohjolainen T, et al. Active Valamatos MJ, Tavares F, Santos RM, Veloso AP, Mil-Homens P. Influence of full Marušič J, Vatovec R, Marković G, Šarabon N. Effects of eccentric training at long- Bourne MN, Duhig SJ, Timmins RG, Williams MD, Opar DA, Al Najjar A, et al. de Boer MD, Morse CI, Thom JM, de Haan A, Narici MV. Changes in antagonist Silva-Batista C, Mattos EC, Corcos DM, Wilson JM, Heckman CJ, Kanegusuku H, et Kubo K, Ishigaki T, Ikebukuro T. Effects of plyometric and isometric training on 46 598 34. 599 et al. Task-specific resistance training to improve the ability of activities of daily living- 600 impaired older adults to rise from a bed and from a chair. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(11):1418- 601 27. 602 35. 603 Stretching versus strength training in lengthened position in subjects with tight hamstring 604 muscles: a randomized controlled trial. Man Ther. 2010 Feb;15(1):26-31. 605 36. 606 strength and flexibility training, combined or isolated, on strength and flexibility gains. J 607 Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(4):1083-8. 608 37. 609 term effects of neck and shoulder resistance training in video display unit workers with work- 610 related chronic neck pain-a pilot randomized trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;36(10):2325-33. 611 38. 612 Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2nd Ed.). Chichester (UK): John Wiley & 613 Sons; 2019. 614 39. 615 reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097. 616 40. 617 Sports Medicine. 2002;36(2):124. 618 41. 619 revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2019;366:l4898. 620 42. 621 prospective association between objectively measured sedentary time, moderate-to-vigorous Alexander NB, Galecki AT, Grenier ML, Nyquist LV, Hofmeyer MR, Grunawalt JC, Aquino CF, Fonseca ST, Goncalves GG, Silva PL, Ocarino JM, Mancini MC. Leite T, De Souza Teixeira A, Saavedra F, Leite RD, Rhea MR, Simão R. Influence of Caputo GM, Di Bari M, Naranjo Orellana J. Group-based exercise at workplace: short- Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic Bleakley C, MacAuley D. The quality of research in sports journals. British Journal of Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a Skrede T, Steene-Johannessen J, Anderssen SA, Resaland GK, Ekelund U. The 47 622 physical activity and cardiometabolic risk factors in youth: a systematic review and meta- 623 analysis. Obes Rev. 2019 Jan;20(1):55-74. 624 43. 625 Cochrane; 2020. 626 44. 627 Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: 628 The Cochrane Collaboration The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. p. 243-96. 629 45. 630 the dangers of unobserved heterogeneity in meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69930. 631 46. 632 in sports medicine and exercise science. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Jan;41(1):3-13. 633 47. 634 2002 Jun 15;21(11):1539-58. 635 48. 636 simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997 Sep 13;315(7109):629-34. 637 49. 638 adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000 Jun;56(2):455-63. 639 50. 640 recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 641 Jun;98(23):e15987. 642 51. 643 critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised 644 studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Bmj. 2017 Sep 21;358:j4008. Drahota A, Beller E. RevMan Calculator for Microsoft Excel [Computer software]: Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Kontopantelis E, Springate DA, Reeves D. A re-analysis of the Cochrane Library data: Hopkins WG, Marshall SW, Batterham AM, Hanin J. Progressive statistics for studies Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and Shi L, Lin L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: practical guidelines and Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a 48 645 52. 646 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 647 2011 Apr;64(4):383-94. 648 53. 649 training on shoulder strength and active movements in children with Erb’s palsy. Int J 650 Pharmtech Res. 2016;9(4):25-33. 651 54. 652 of a 6-Week Junior Tennis Conditioning Program on Service Velocity. J Sports Sci Med. 2013 653 Jun;12(2):232-9. 654 55. 655 Silva-Grigoletto ME. Comparison between functional and traditional training exercises on joint 656 mobility, determinants of walking and muscle strength in older women. J Sports Med Phys 657 Fitness. 2019 Oct;59(10):1659-68. 658 56. 659 strengthening, stretching and comprehensive exercise program on the strength and range of 660 motion of the shoulder girdle muscles in upper crossed syndrome. Med Sport. 2016;69(1):24- 661 40. 662 57. 663 stretching exercise programmes on kinematics and kinetics of running in older adults: A 664 randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(18):1774-81. 665 58. 666 versus stretching only in the treatment of patients with chronic neck pain: A randomized one- 667 year follow-up study. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(7):592-600. 668 59. 669 Resistance training combined with stretching increases tendon stiffness and is more effective Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: Al-Wahab MGA, Salem EES, El-Hadidy EI, El-Barbary HM. Effect of plyometric Fernandez-Fernandez J, Ellenbecker T, Sanz-Rivas D, Ulbricht A, Ferrauti A. Effects de Resende-Neto AG, do Nascimento MA, de Sa CA, Ribeiro AS, Desantana JM, da Hajihosseini E, Norasteh A, Shamsi A, Daneshmandi H, Shahheidari S. Effects of Fukuchi RK, Stefanyshyn DJ, Stirling L, Ferber R. Effects of strengthening and Häkkinen A, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, Ylinen J. Strength training and stretching Kalkman BM, Holmes G, Bar-On L, Maganaris CN, Barton GJ, Bass A, et al. 49 670 than stretching alone in children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Front 671 Pediatr. 2019;7:Article 333. 672 60. 673 stretching: Effects on flexibility and strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(12):3391-8. 674 61. 675 interventions on optimal lengths of hamstring muscle-tendon units. J Sci Med Sport. 676 2020;23(2):200-5. 677 62. 678 on active and passive ranges of movement in dancers: A randomized controlled trial. J Strength 679 Cond Res. 2013;27(11):3053-9. 680 63. 681 flexibility training in older adults? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995 Oct;27(10):1444-9. 682 64. 683 elderly women: effect upon flexibility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988 Apr;69(4):268-72. 684 65. 685 of strength and flexibility training on skeletal muscle electromyographic activity, stiffness, and 686 viscoelastic stress relaxation response. Am J Sports Med. 1997 Sep-Oct;25(5):710-6. 687 66. 688 flexibility training in healthy young adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Nov;19(4):842-6. 689 67. 690 strength, flexibility, and simultaneous training on flexibility and strength gains. J Strength 691 Cond Res. 2011 May;25(5):1333-8. 692 68. 693 strengthening exercises has more effects on scapular muscle activities and joint range of motion Morton SK, Whitehead JR, Brinkert RH, Caine DJ. Resistance training vs. static Li S, Garrett WE, Best TM, Li H, Wan X, Liu H, et al. Effects of flexibility and strength Wyon MA, Smith A, Koutedakis Y. A comparison of strength and stretch interventions Girouard CK, Hurley BF. Does strength training inhibit gains in range of motion from Raab DM, Agre JC, McAdam M, Smith EL. Light resistance and stretching exercise in Klinge K, Magnusson SP, Simonsen EB, Aagaard P, Klausen K, Kjaer M. The effect Nóbrega AC, Paula KC, Carvalho AC. Interaction between resistance training and Simão R, Lemos A, Salles B, Leite T, Oliveira É, Rhea M, et al. The influence of Chen Y-H, Lin C-R, Liang W-A, Huang C-Y. Motor control integrated into muscle 50 694 before initiation of radiotherapy in oral cancer survivors with neck dissection: A randomized 695 controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237133-e. 696 69. 697 Short-term strength and balance training does not improve quality of life but improves 698 functional status in individuals with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a randomised controlled 699 trial. Diabetologia. 2019 2019/12/01;62(12):2200-10. 700 70. 701 squat produces greater neuromuscular and functional adaptations and lower pain than partial 702 squats after prolonged resistance training. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020 Feb;20(1):115-24. 703 71. 704 back extensor strength training in postmenopausal osteoporotic women with vertebral 705 fractures: comparison of supervised and home exercise program. Arch Osteoporos. 2019 Jul 706 27;14(1):82. 707 72. 708 Influência do treinamento de força muscular e de flexibilidade articular sobre o equilíbrio 709 corporal em idosas. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2012;15:17-25. 710 73. 711 of resistance training on body composition, self-efficacy, depression, and activity in 712 postpartum women. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014 Apr;24(2):414-21. 713 74. 714 controlled trial of muscle strengthening versus flexibility training in fibromyalgia. J 715 Rheumatol. 2002 May;29(5):1041-8. 716 75. 717 Flexibility of High School Males. J Athl Train. 2004;39(3):254-8. Venkataraman K, Tai BC, Khoo EYH, Tavintharan S, Chandran K, Hwang SW, et al. Pallarés JG, Cava AM, Courel-Ibáñez J, González-Badillo JJ, Morán-Navarro R. Full Çergel Y, Topuz O, Alkan H, Sarsan A, Sabir Akkoyunlu N. The effects of short-term Albino ILR, Freitas CdlR, Teixeira AR, Gonçalves AK, Santos AMPVd, Bós ÂJG. LeCheminant JD, Hinman T, Pratt KB, Earl N, Bailey BW, Thackeray R, et al. Effect Jones KD, Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM, Potempa KM. A randomized Nelson RT, Bandy WD. Eccentric Training and Static Stretching Improve Hamstring 51 718 76. 719 limb range of motion measurements in recreational dancers. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 720 Oct;23(7):2144-8. 721 77. 722 guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence - inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 723 Dec;64(12):1294-302. 724 78. 725 Assess the Perception of Stretching Intensity. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning 726 Research. 2015;29(9). 727 79. 728 al. Resistance training and detraining effects on flexibility performance in the elderly are 729 intensity-dependent. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(3):634-42. 730 80. 731 Femoris Architecture and Strength: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. J Athl Train. 732 2020 May;55(5):501-14. 733 81. 734 versus conventional resistance training in older humans. Exp Physiol. 2009 Jul;94(7):825-33. 735 82. 736 Jimeno-Serrano FJ, Collins SM. Predictive factors of adherence to frequency and duration 737 components in home exercise programs for neck and low back pain: an observational study. 738 BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2009;10:Article 155. Wyon MA, Felton L, Galloway S. A comparison of two stretching modalities on lower- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Woodcock J, Brozek J, Helfand M, et al. GRADE Freitas SR, Vaz JR, Gomes L, Silvestre R, Hilário E, Cordeiro N, et al. A New Tool to Fatouros IG, Kambas A, Katrabasas I, Leontsini D, Chatzinikolaou A, Jamurtas AZ, et Gérard R, Gojon L, Decleve P, Van Cant J. The Effects of Eccentric Training on Biceps Reeves ND, Maganaris CN, Longo S, Narici MV. Differential adaptations to eccentric Medina-Mirapeix F, Escolar-Reina P, Gascón-Cánovas JJ, Montilla-Herrador J, 739 52 View publication stats