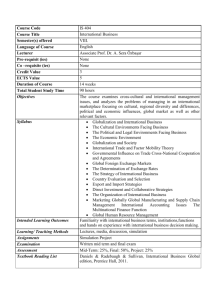

National Environmental Differences in International Business

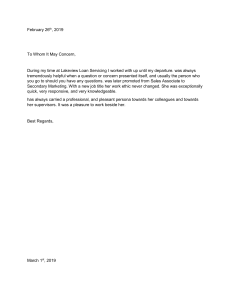

advertisement