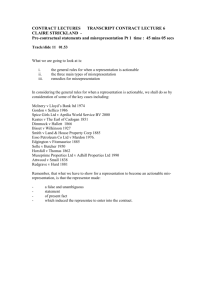

Law 301 Midterm Guide: Third-Party Beneficiaries & Contingent Agreements

advertisement

LAW 301 MIDTERM GUIDE Third-party Beneficiaries In Canada, the general rule (known as privity of contract) is that only a signatory to a contract may sue upon it, except where there is a third-party beneficiary who has rights under that contract. A THIRD PARTY BENEFICIARY CANNOT SUE A PROMISOR: the leading cases are Tweedle and Dunlop Tweddle v Atkinson A third party beneficiary has the right to sue if the beneficiary gave some consideration. Without any consideration the third party beneficiary has no right to sue on a contract. The way consideration works is the it has to move from the promise to the third party beneficiary. The case of Tweeddle establishes the common law principle of privity of contract. The general rule under the common law is that a person who has not provided consideration for an agreement cannot sue in contract law to enforce it. Consideration must move from the person seeking to enforce the contract. The Court decided that Tweedle Jr's suit would not succeed as no stranger to the consideration may enforce a contract, although made for his benefit. The court ruled that a promisee cannot bring an action unless the consideration from the promise moved from him. Consideration must move from party entitled to sue upon the contract. No legal entitlement is conferred on third parties to an agreement. Third parties to a contract do not derive any rights from that agreement nor are they subject to any burdens imposed by it. Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v Selfridge & Co Ltd This case dealt with three principles of contract. Test: 1. Only a person who is a party to a contract can sue on it 2. A person with whom a contract not under seal has been made is able to enforce it only if consideration is given to the promisor or some other person at the promisor’s request 3. A principal not named in the contract may sue upon it if the promisee really contracted as his agent, but he must have given consideration personally or through the promise 1. Was the appellant a party in the contract done between Dew and Selfridge? In this case Dunlop was not entitled to enforce the contract against Selfridge because it was not a party to the contract. 2. Can the appellant sue the respondent without any contractual relationship? We here find that the appellants could not sue the respondents as they were not aparty to the cont ract between the dealers and the respondents 3. Was Dew & Co. acting as an agent of appellants while contracting with Selfridge? Even if Dew was recognized to be acting as Dunlop’s agent, appellants still couldn’t maintain the action as there was no consideration between them and Selfridge. In this case Dunlop was not entitled to enforce the contract against Selfridge because it was not a party to the contract. A THIRD PARTY BENEFICIARY CAN AQUIRE A BENEFIT: the privity rule will not always prevent a third party from receiving a benefit. A 3PB HAS A RIGHT TO SUE 1. Statute (true exception) 2. Specific Performance [or action by promise or promisee’s estate] 3. Trust 4. Agency A 3PB HAS A RIGHT TO DEFENCE ONLY 5. Employment (true exception) 6. Subrogation (true exception) A. STATUTE Sometimes, a statute will expressly allow a third party to sue under a contract, even though she is not a party to the contract. B. SPECIFIC PERMORMANCE This exception applies when the third party beneficiary persuades the promisee (or more often the promisee’s estate) to sue the promisor for specific performance, to force the promisor to perform its contractual obligations. The third party isn’t suing—the promisee or his estate is—so the privity rule isn’t offended. The leading cases of specific performance is Beswick. Beswick v Beswick (Court of Appeal) This case demonstrates some of the ways the courts tried to avoid the limitations of the privity of contract rule. In the modern era, the wife would likely be able to sue in her own right under the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999. The Court in this case found that the wife could only sue in her capacity as administrator of her husband’s estate. The woman could not sue in her own personal capacity as she was not a party to the original agreement. The rules of Beswick are the following: Third parties cannot sue for breach of contract when they were not a party to the contract, even if they were named as a beneficiary of the contract. Executors of wills can sue for specific performance of promises made in contracts with the deceased. C. TRUST A trust may be created in different ways. A person (called the settlor) may, gratuitously or for consideration, transfer property or rights to a trustee to be held or managed for the benefit of a third party (called the cestui que trust or beneficiary). Alternatively, again gratuitously or for consideration, a person may declare himself or herself to hold property or rights as trustee for the benefit of a specified beneficiary. Once a trust is created, the beneficiary is entitled to enforce the trust obligation directly. IMPORANT: The key to establishing a trust relationship is intention. The case of Vandepitte illustrates that it is not always easy to show intention. Vandepitte v Preferred Accident Insurance Co This case established that there must be clear intention to create a trust in order for a trust relationship to be found. Also a cestui que trust (the beneficiary of a trust) can sue on a contract made by the trustee for their benefit. Test: A trust will only arise to benefit a third party beneficiary in the circumstances where it is clear that the parties actually intended to create a trust relationship. D. AGENCY There is a special relationship between the promisee and the third party beneficiary, whereby the promisee, as agent, is in fact entering into the contract on behalf of the third party beneficiary, who is the principal. Agency relationships can be created in a number of different ways. 1) By legislation: e.g., under the Partnership Act, RSBC 1996, c 348. 2) At common law based on the nature of the relationship: e.g., marriage. 3) By contract: e.g., real estate contracts, power of attorney contracts, representation agreements, or specialized business contracts as in the next two cases. The leading cases of agency are McCannell and New Zealand Shipping Co Ltd McCannell v Mabee McLaren Motors Ltd If the promise is contracting as agent on behalf on a third party, the doctrine of privity has no application between the third party and promisor. Each party to an agent by promise to be bound is sufficient consideration for a contract. (McCannell v Mabee McLaren Motors) The term agent does not need to be used to establish an agency relationship exists. New Zealand Shipping Co Ltd v AM Satterthwaite & Co Ltd (Eurymedon) 1. The third party was intended to receive the benefit under the contract 2. The promissor is acting as agent for the third party 3. The promissor has authority from the third party to act as its agent 4. Consideration must move from the third party. E. Employment London Drugs Ltd v Kuehne & Nagel International Ltd [London Drugs] Employee exception test: 1. The limitation of liability clause must either expressly or by implication extend its benefit to the employees who seek to rely on it. 2. The employees seeking the benefit of the clause must have been acting in the course of their employment and must have been performing the very services provided for in the contract between their employer and the customer when the loss occurred. F. Principled Exception Fraser River Pile & Dredge Ltd v Can-Dive Services Ltd [Can-Dive] Expansion of London drug test: 1. The parties to the contract must have intended the relevant provision to confer a benefit on the third party. 2. The third-party must demonstrate that their actions came within the scope of the agreement between the initial parties. 3. The third party must have been acting within the course of the agreement when the loss had occurred, and the status and activity of the third party are within the contemplation of the contract. Contingent Agreements What is a Contingent Agreement? Contingent agreements are contracts that have conditions built into them that protect the parties in case some defined event occurs or does not occur. The contract is characterized as "contingent" because the terms are not final and are based on certain events or conditions occurring Types of Conditions attached to Contingent Agreements 1. Condition Precedent: A condition precedent is a condition or an event that must occur before a rights, claim, duty or interest arises. For example, an insurance contract may require the insurer to pay to rebuild the customer’s home if it is destroyed by fire during the policy period. The fire is a condition precedent. The fire must occur before the insurer is obligated to pay. The onus of proving that a condition precedent has been satisfied is on the party wishing to enforce the contract, usually the plaintiff. 2. Condition Subsequent: A condition subsequent is an event or state of affairs that, if it occurs, will terminate one party’s obligation to the other. For example, a contract might state something like: the client will pay for the haircut, unless the hairdresser does not perform the haircut. In this case, the client has a contractual duty to pay for the haircut, and this obligation will only end if the hairdresser does not perform. In other words, in order to prove that they are no longer bound, the client must prove that the haircut never occurred. The onus of proving that a condition subsequent has occurred is on the party wishing to be relieved of his obligations under the contract, usually the defendant. How to determine if a contingency agreement was made with a condition precedent on a condition subsequent? 1. Intention: Whether or not a condition precedent precedes formation of a contract or precedes performance depends on the intention of the parties as determined by the wording used and the surrounding circumstances. For example: Wording such as “There is no binding contract until xyz event occurs” or “This offer is conditional until...” suggests an intention that no contract is formed until the event happens. On the other hand a clause stating that “Upon acceptance parties will have a binding contract” indicates an intention that the parties want a binding contract in place despite the existence of a condition precedent. 2. Certainty: If the language used to describe a condition precedent is so vague that the court can ascribe no meaning to it then, unless the condition can be waived, any intended contract, conditional or otherwise, will be void for uncertainty. Some courts have held that expressions like “suitable” or “satisfactory” in connection with defined events such as financing or inspection are too vague to be enforced. The lesson to be learned is that it’s better not to take a chance with vague language if you can avoid it. 3. Consideration: Similarly, the parties’ intentions may be defeated if there is no consideration. This can arise in cases where the contract includes a condition precedent intended to precede performance which is entirely subjective or “illusory”. For example: If a purchaser negotiates a real estate “contract” with a term that her obligation to pay the purchase price at the time of completion is subject to her “still liking the place”. In effect, what a purchaser has tried to do is create an option in her favour. Wiebe v Bobsien (1985 BCSC) There was a condition precedent which cannot be revoked. The parties intended the interim agreement to be binding. Therefore, the offeree was to use his best efforts to sell his house, and if and when he sold his house, then the offeror would be obliged to sell his house to the offeree. The court implied the terms “best efforts”. To avoid uncertainty or interpretation difficulties, the parties should spell out in the interim agreement that the purchaser would use their best efforts to sell in accordance with the agreement. The condition to sell another property before completing a contract of purchase and sale was both subjective and objective, but ultimately it was considered too subjective. If it is the intention of the parties to enter into a binding agreement, CP suspends the performance of the C pending satisfaction of the condition Subsidiary Obligations Subsidiary obligations can include a requirement to use reasonable efforts to make sure a condition precedent comes about. For example, if a sale is made “subject to financing”, a court may imply an obligation that the purchaser must use reasonable efforts to obtain financing and not reject financing unreasonably. Dynamic Transport Ltd v OK Detailing Ltd (1978 SCC) [Dynamic Transport] If you have entered into a binding agreement of purchase and sale that includes conditions that must be satisfied or waived by the closing, you are under an obligation to act in good faith to take reasonable steps to ensure that those conditions are satisfied. Any indication that a party is not acting in good faith resulting in a failure to satisfy or waive a condition could be grounds for a claim for breach of contract seeking full performance and closing of the transaction in question, or alternatively a claim for damages arising from the failure to close including forfeiture of deposits. Rule: Every party is under an obligation to do all that’s necessary on their part to secure performance of the contract. Remedies for Breach of Subsidiary Obligations 1. Expectation Damages: damages recoverable from a breach of contract by the nonbreaching party. An award of expectation damages protects the injured party's interest in realising the value of the expectancy that was created by the promise of the other party. 2. Specific Performance: An equitable remedy available for breach of contract. A declaration by the court compelling a party to perform its contractual obligations. It may be granted in addition to or instead of damages. Eastwalsh Homes Ltd v Anatal Developments Ltd (1993 Ont CA) [Eastwalsh Homes] The general rule is that the breach must cause the loss. “The burden is on the plaintiff to establish on the balance of probabilities that as a reasonable and probable consequence of the breach of contract, the plaintiff suffered the damages claimed. Ratio: If a contract fails due to an external element, the courts will still not award damages for breach if the chances of success were extremely low. When assessing if the defendant used their best efforts to perform the contract the following is important. “Best efforts” means taking, in good faith, all reasonable steps to achieve the objective, carrying the process to its logical conclusion and leaving no stone unturned. “Best efforts” includes doing everything known to be usual, necessary and proper for ensuring the success of the endeavour. The meaning of “best efforts” is “ not boundless. It must be approached in light of the particular contract, the parties to it and the contract's overall purpose as reflected in its language. Unilateral Waiver Either you or we may, by written notice, unilaterally waive or reduce any obligation of or restriction on the other party under this Agreement. The waiver or reduction may be revoked at any time for any reason on ten (10) days' written notice. Turney v Zhilka (1959 SCC) Ratio: A condition can be waived if a term is for the sole benefit of one party, the condition is not a true condition precedent and the condition is severable. Condition precedent is an external condition upon which the existence of the obligation depends (a home sale depends on approval of bank mortgage loan). Section 54 of the Law and Equity Act permits a party to unilaterally waive a true condition precedent if the condition is for its sole benefit, is severable from the contract, and the waiver is made within a stipulated or reasonable time. Conditions precedent 54 If the performance of a contract is suspended until the fulfillment of a condition precedent, a party to the contract may waive the fulfillment of the condition precedent, even if the fulfillment of the condition precedent is dependent on the will or actions of a person who is not a party to the contract if (a) the condition precedent benefits only that party to the contract, (b) the contract is capable of being performed without fulfillment of the condition precedent, and (c) where a time is stipulated for fulfillment of the condition precedent, the waiver is made before the time stipulated, and where a time is not stipulated for fulfillment of the condition precedent, the waiver is made within a reasonable time. REPRESENTATIONS AND TERMS:CLASSIFICATIONS AND CONSEQUENCES There are statements made without contractual intent, or as mere representations, which are not terms of the contract but can lead to the limited legal consequences, or a statement may be construed as a term of the contract, leading to more serious legal liabilities in the event that it is broken. “Mere puffs” or general sales talk does not represent misrepresentation. Statements of opinion of belief are also not considered as misrepresentation. Though lying about your opinion can be negligent and therefore actionable in tort. Misrepresentation must be (1) unambiguous, (2) material (it must be one which would affect the judgment of a reasonable person in deciding whether or on what terms to enter into the contract without making such inquiries as he would otherwise make), or (3) relied on by the representee. Misrepresentation and Recission A misrepresentation is a representation that is false. A misrepresentation is fraudulent when either the misrepresentor knew that the statement was false or made the statement recklessly and without care, whether it was true or false. Recission is the remedy for misrepresentation. A case that represent misrepresentation and tort is the Redgrave case which showcases the reliance rule. Redgrave v Hurd (1881 Eng CA) [Redgrave] In this case it was established that a contract can be rescinded for innocent misrepresentation, even where the representee also had the chance to verify the false statement. This is because where a party to a contract makes a misrepresentation which a reasonable person would rely on when deciding to contract, or which is intended to induce the contract, the courts will assume that the defendant relied on the misrepresentation. This is known as a ‘material’ representation. To rebut this assumption, the party must show that the defendant actually knew of facts which made the statement untrue, or that his words or conduct made clear that he did not rely on the statement. RULE OF RELIANCE More generally, showing that a party had the means and opportunity to learn the truth, but failed to, does not prove that there was no reliance for the purposes of misrepresentation. This is true whether or not the misrepresentation is ‘material’. In innocent misrepresentations you can only ask for damages if you cannot rescind the contract. Reasonable Opportunity to Discover the Truth If the representor has special knowledge of facts that the representee does not have and these facts would make the opinion in question unreasonable, then it amounts to an actionable misrepresentation. A merely statement of opinion will not amout to misrepresentation as was in the case of Smith v Land. Smith v Land and House Property Corp. (1884 Eng CA) This case established that a statement of opinion, from a knowledgeable party to one who is not, is a representation. If false, it is actionable and will be a misrepresentation. Innocent misrepresentation allows for recission. The reasonableness of your reliance on a statement is irrelevant for recission, but it is relevant for recovery of damages in tort. Misrepresentation by Omission or Silence Misrepresentation by omission is not actionable, nor can it be the basis of a defence. However, an exception to this rule is where a fiduciary duty to disclose material. The case that deals with this is Bank of BC. Bank of BC v Wren Developments Ltd (1973 BCSC) This case established that failures or omissions can qualify as a misrepresentation especially if there is an active concealment of the truth. Negligent misrepresentation permits rescission. Indemnification Indemnification can be raised in rescission. You must be required to do something as stated in the contract to be able to seek indemnification. In tort, the question is had the plaintiff known the truth, would they have entered into the contract? If the answer is no, but for the tort, could they have been engaged in profitable endeavors at another location. In tort, it is an apportunity cost issue. The case of Kupchak dealt with this. Kupchak v Dayson Holdings Ltd (1965 BCCA) [Kupchak] In this case it was established that in situations where the misrepresentee is not entitled to claim recission include: 1. When the rights of a third party intervene 2. When there is election or affirmation 3. When there is laches or delay 4. When rescission would cause radical injustice to misrepresentor 5. When there is innocent misrepresentation and the contract has been exectuted. Recission of a contract is an option even when complete restitution cannot be reachedwhen compensation can be awarded to make up the difference. The Execution Rule/Limitation Rule This rule states that for innocent misrepresentations the right to rescission ends with the execution of the contract (that is, performance or completion), unless the misrepresentation is so serious that it changes the substance of the contract. This is explained in the case of Redican. The execution rule/limitation in relation to the rescission remedy only applies to innocent misrepresentations (that’s why it wasn’t argued in Kupchak). Redican v Nesbitt (1923 SCC) [Redican] In this case it was established that an executed contract for real property cannot be rescinded for innocent misrepresentation unless the property is "different in substance". What is a term and what is a representation? A term= a statement made for which that party intended to give an absolute guarantee. TEST OF INTENTION= a term was intended to be guaranteed strictly. If a statement is deemed to be a term and not a mere representation then a person can sue for damages as opposed to only recission. The case of Heilbut explains this. Heilbut, Symons & Co v Buckleton (1913 HL) [Heilbut, Symons] This case established that a term is a statement made for which the party intended to give an absolute guarantee. This case also established the following: Parties are not liable for damages arising from their own innocent misrepresentations. Damages are only awarded for fraudulent or reckless misrepresentations, or misrepresentations that refer to a material issue that fundamentally change the contract. Innocent representations are only referred to as warranties if they have clearly been intended to be warranties by the parties. Dick Bentley Productions Ltd v Harold Smith (Motors) Ltd (1965 Eng CA) [Dick Bentley] This case established that anything said to induce a party to enter into a contract becomes a term in the contract, although this approach has not been adopted. The Court of Appeal dismissed an appeal by the defendants. Judged by the reasonable bystander standard, the Court found that the representation by the defendants would induce a reasonable party to enter the contract and indeed, did so in Dick Bentley Productions Ltd v Harold Smith (Motors) Ltd. The representation about the mileage was a warranty, since the defendants failed to show that it was a misrepresentation made innocently. Therefore, he was bound by that representation and was liable for breach of warranty. Classification of Terms including conditions, warranties and intermediate terms Terms in a contract are characterized at the time of acceptance and can be subdivided into three types of terms which determine what the consequences of breach of the term will be: 1. Condition= a statement of fact which forms an essential term in the contract Remedy= damages and the innocent party can treat the contract as repudiated= the contract comes to an end, the #1 obligations are terminated but the #2 obligations remain. 2. Intermediate Term (Innominate) Remedy= determined after the breach occurs based on the seriousness of the consequences of the breach not the breach itself and uses either of the remedies for condition or warrany. (Hong Kong Fir Shipping case) 3. Warranty= a term which is not essential to the contract and is collateral to the main purpose of the contract. Remedy= unless stipulated otherwise in the contract, the only remedy is damages and proving harm was done is necessaty. Leaf v International Galleries (1950 Eng CA) [Leaf] In this case it was established that there was a breach of contract, but repudiation is barred by the lapse of reasonable time. It was also established that innocent misrepresentation is less potent than breach of condition, a fortiori, a claim to rescission on the ground of innocent misrepresentation is also barred. Concurrent Liability in Contract and Tort “True” concurrent liability occurs where a plaintiff has a claim for damages in contract and tort, arising out of the same incident. The case of BC Checo dealt with this. RULE: The only real exception to concurrent liability is where there is a valid exclusion clause in the contract excluding liability in tort. BG Checo International Ltd. v British Columbia Hydro & Power Authority The Court held that there is a prima facie presumption that a claimant is able to sue concurrently in tort and contract where sufficient grounds exist. Still, liability in tort will still be subject to an exemptions or conditions set out in a contract. The Court considered three situations where a party can sue in tort and contract. 1. "where the contract stipulates a more stringent obligation than the general law of tort would impose. In that case, the parties are hardly likely to sue in tort, since they could not recover in tort for the higher contractual duty." Though the right to sue in tort still exists, it is generally not practical. 2. "where the contract stipulates a lower duty than that which would be presumed by the law of tort in similar circumstances." This does not necessarily extinguish the right to sue in tort unless it is explicit in the contract. 3. "where the duty in contract and the common law duty in tort are co-extensive." In such cases, "the plaintiff may seek to sue concurrently or alternatively in tort to secure some advantage peculiar to the law of tort, such as a more generous limitation period." The Court found that the current situation fell into the third category and so BG Checo was able to sue in both tort and contract. Nunes Diamonds Ltd. v. Dominion Electric Protection Company In the Diamonds case it was established that negligent misrepresentation is inapplicable to a relationship that is governed by a contract, unless the negligence relied on is an “independent tort” unconnected with the performance of that contract Central Trust Co. v. Rafuse 1. In this case the question was can a solicitor be liable to a client in tort as well as in contract for negligence in the performance of the professional services for which the solicitor has been retained? On the first issue, The court held that the duty in tort and in contract are two entirely separate duties and can be held concurrently by a defendant. The difference between conditions and warranties The case of Hong Kong defines conditions and warranties, and introduces the innominate term. Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd This issue of this case was whether a breach of contract was sufficient to entitle the other party to repudiate the contract Ratio: The correct test to determine if a breach should lead to repudiation is to look at the events which have occurred as a result of the breach and to decide if these events deprived the party attempting to repudiate of the benefits that it expected to receive from the contract (the breach must lead to the party not being able to obtain all or a substantial proportion of the benefits that they intended to receive by entering into the contract)- if they do, then repudiation is in order, else only damages can be awarded. Frustration: the event deprived the party who has further undertakings still to perform of substantially the whole benefit of the contract (Hong Kong Fir) The correct test to determine if a breach should lead to repudiation is to look at the events which have occurred as a result of the breach and to decide if these events deprived the party attempting to repudiate of the benefits that it expected to receive from the contract (the breach must lead to the party not being able to obtain all or a substantial proportion of the benefits that they intended to receive by entering into the contract) - if they do, then repudiation is in order, else only damages can be awarded. Wickman Machine Tool Sales Ltd v L Schuler AG (1974 HL) Placing labels on terms in a contract does not imply the legal definition of the label onto the term. Legal definition of condition “A term the breach of which by one party gives to the other an option either to terminate the contract or to let the contract proceed and, if he so desires, sue for damages for the breach” When is a term a condition? A term may be a condition giving the option to terminate because: o “it is of a fundamental character going to the root of the contract” or o “the parties have chosen to stipulate that it shall have that effect” Effect of using the word “condition” The inclusion of the word ‘condition’ is an indication of intention but is not conclusive Whether the term of a contract is a condition depends on the intention disclosed by the contract as a whole The more unreasonable a result the more unlikely it is that the parties intended it Ratio: 1. A term described as a “condition” in a commercial contract does not compel the court to hold that it is a condition in the strict sense and the question of intention will be decided by construing the contract as a whole. 2. In construing a contract, the court cannot take the conduct of the parties subsequent to the execution of the contract into account whilst making a decision or giving judgement. Duty to perform in good faith The case of Bhasin deals with good faith. Bhasin v Hrynew (2014 SCC) In this case the Supreme Court of Canada recognized good faith in contractual performance to be a ‘general organizing principle’ of the common law of contract. Specifically, the SCC held that: The organizing principle of good faith is that parties generally must perform their contractual duties honestly and reasonably and not capriciously or arbitrarily; The development of the principle of good faith should not be used as a pretext for scrutinizing the motives of contracting parties; The new duty of honesty does not impose a duty of fiduciary loyalty, or of disclosure, or require a party to forego advantages flowing from the contract; The duty of honesty should be thought of as a general doctrine of contract law that operates irrespective of the intentions of the parties, analogous to the doctrine of unconscionability; and The precise content and scope of honest performance will vary with context, however, parties are not free to exclude the duty of honest performance, and any modification of the duty must be in express terms. Remedies for the party in default The case of Fairbanks explains this. Fairbanks Soap Co v Sheppard (1953 SCC) Price cannot be recovered when there is a contract to do work for a lump sum, until the work is completed A contract can be substantially completed where some item of the work has beendone negligently/improperly but not where there has been abandonment of the contract Sumpter v Hedges (1898 Eng CA) Firstly, the Court held that, under a contract of work for a lump sum payment, the contractual price cannot be recovered, neither in whole nor in part, until the contractual work is complete. If the work was completed, yet with certain omissions or defects, then the employer would take the benefit of the completed works and the employee would be entitled to payment of the contract price with deductions. However, on the facts, the employee abandoned the contract without completion. This partial performance of the contract works does not entitle the employee to recover any payment of the contract price under a lump sum contract. Secondly, the Court held that, alternatively, quantum meruit payment would require the inference of a new contract for the partial work, independent from the lump sum contract. Yet, on the facts, there is no inference of a new contract for partial works. As the only applicable contract is the lump sum contract, the employee was not entitled to recover the contract price for his partial performance of the contractual works. Howe v Smith (1884 Eng CA) This case dealt with deposits. The position with regard to real estate deposits is that they are non-refundable except in situations where the deposit is so large that it is unconscionable. In this case Lord Justice Fry stated that a deposit was “not merely a part payment, but is then also an earnest to bind the bargain so entered into, and creates by the fear of its forfeiture a motive in the payer to perform the rest of the contract.” A defaulting purchaser may be successful in getting all or part of a deposit returned where the deposit is unconscionably large and where the seller is seeking to disguise a penalty as a deposit. While there is no hard and fast rule about how large a deposit must be in order for it to be unconscionable, deposits comprising 10% of the purchase price have been deemed acceptable by the courts. In the case of Howe v. Smith (1884) 27 Ch. D. 89. , the English Court of Appeal held that the two functions of a deposit are to be: an earnest to bind the bargain, which means the deposit acts as an indication that the purchaser is serious in carrying out the bargain; and a guarantee of due performance, that is, security of the performance. Therefore, if the purchaser doesn’t complete the agreement/contract, it would appear that a deposit may be forfeited. Stevenson v Colonial Homes Ltd (1961 Ont CA) the court will determine if a payment is a deposit, part payment or both having regards to the language of the contract, the circumstances of the case, intention of the parties, the money put down and what was said deposits are generally a small fraction of the purchase price If a contract is neutral, the general rule is that the law confers on the purchaser the right to recover his money Money paid before delivery is one of three things: A deposit, a part payment, or both (deposit until deliver then part payment). If it is a deposit or both, then the buyer has no right to recover it if he or she defaults. However, if it is a part payment, then a buyer has the right to recover no matter what. The presumption is that the buyer can recover, but it is rebuttable if something in the contract points to a deposit or a deposit and part payment. Privity Questions Is the general privity rule/bar just another way of saying that contractual obligations are not binding without consideration? Yes, there is an argument that they are two sides of the same coin. One is the consequence of the other. If you are not a party to the contract, the promisor will not have asked you to supply consideration for any rights or benefits under the contract. Contingent Agreement Questions Assume you are paralegal in BC Hydro’s legal department. Try your hand at drafting a condition precedent that you could use in a $50,000 contract being negotiated with a supplier, where the intention is clear that there is no binding contract between BC Hydro and the supplier until a specified event occurs. You can make up the materials being purchased and the triggering event – the key is phrasing the condition precedent in a way that will clearly express the desired intention. There are many examples that could work here. For example: This contract for the purchase of Acme’s N-D53 capacitor voltage transformer is subject to its passing BC Hydro’s transformer testing protocol (see Appendix 2), and until that time there is no binding contract between the parties. Do you agree with Lambert JA’s decision that the “subject to” clause in this case was purely subjective and uncertain, or with the majority’s approach? See also note 2 on pages 340-41. There is no right answer. The majority’s approach or variations on it are common, however. “Subject to selling my house” can become less illusory and uncertain by implying an obligation to use reasonable efforts in selling the house. What efforts would a reasonable person, or a reasonable person in the purchaser’s position, make to sell the house, and what price would be reasonably acceptable? The purchaser’s actual conduct in trying to satisfy the condition precedent would be measured against a reasonableness standard. It is common for the courts to imply a term that one of the parties use “reasonable efforts” to bring about the event specified in the condition precedent, such as financing or subdivision approval. Do the courts also require “good faith” in making those efforts? See page 345, notes 2-3. Yes, they do, at least for some conditions precedent. The Supreme Court of Canada in Bhasin cited Dynamic Transport with approval, and confirmed that it is appropriate to impose a good faith obligation on a vendor who is seeking subdivision approval, because this is the type of contract that requires the cooperation of the parties to achieve the objects of the contract. This means that passing a reasonable efforts test (looking at what an average, reasonable person would do) might not be enough if, in the circumstances, the party in question (perhaps an informed, sophisticated person not lacking in resources) could have done more but deliberately held back to avoid going through with the deal. Do you agree with the decision in Turney v Zhilka that if satisfaction of the condition precedent depends on the will of a third party it can’t be unilaterally waived? There is no right answer, but there are questions why such an absolute bar should exist. Is the purchaser really rewriting the contract by waiving this condition? Why should the involvement of a third party be relevant to whether a condition precedent can be waived? Conditions not involving third parties can be waived. If one party alone benefits from the provision and wants to waive it, why should she not be allowed to? The rule has been abolished in BC as mentioned in the lecture notes. An easy statutory interpretation question: Does s 54 of the Law and Equity Act set out a conjunctive list of conditions (all conditions must be satisfied) or a disjunctive list (only one must be satisfied)? A conjunctive list: Under this provision, all three requirements have to be met before a party can unilaterally waive a condition precedent, whether it’s a true condition precedent or not. See also page 355, note 7. Representation and Terms Questions Was the defendant in Redgrave fully restored to the position he was in before he entered the contract? No, he also suffered damages, which would not be covered under the rescission remedy. Is the idea of a presumption of reliance (when claiming rescission for material misrepresentations) the law in Canada? No, the Canadian approach appears to be that the claimant must prove reliance (that is, there is no presumption): see the LK Oil & Gas case as described in note 3. However, in most cases it won’t make much of a difference. If the misrepresentation is material, it will be relatively easy to prove to the court that the claimant was in Besides cases where the parties owe each other fiduciary obligations, can you think of other situations where there is or should be an obligation to disclose information, contrary to the general rule that silence is not actionable? Other situations where the courts have recognized an obligation to disclose include: 2) changed circumstances (if a party has made a representation during negotiations that is true at the time, but before agreement the circumstances change so that it is no longer true, there will be an obligation to bring the change to the other party’s attention) 2) half-truths (if a party has only told half the story, there will be an obligation to tell the other half, if failing to do so would be misleading) 3) deliberate concealment (if a party has concealed a defect that would otherwise be discoverable, there will be an obligation to disclose the existence of the defect). Why did the Court in Kupchak reject the defendants’ restitution argument? Generally, if the consideration provided by the claimant cannot returned in the form in which it was given, then the rescission remedy will not be granted. However, in cases such as this one, where the other party has been guilty of fraud, the courts are more flexible. So, even though the vendor (Dayson Holdings) had altered and sold a half interest in one of the properties they had received for the sale of the motel, the rescission claim still succeeded. The fraudulent vendor was required to substitute money/compensation in place of the Haro street property, which they could no longer return (based on its value the day after completion together with interest). Locate where in the judgment in Kupchak the Court cited the rules relating to affirmation and laches, and describe why both these defences did not apply on these facts. The affirmation rule is set out at the bottom of page 372 (from Halsbury’s Laws) and the laches rule near the top of page 373 (the Lindsay Petroleum quote). The affirmation defence was unsuccessful because the Kupchaks had no choice but to continue operating the motel after they had knowledge of the fraud. If they had walked away from the deal at that point, the value of the motel would have diminished significantly and they would not have been able to return it in the form in which they received it. The laches/delay defence also failed. The defendant vendor was not misled by the delay in commencing the rescission claim. The Kupchaks had put the vendor on notice as soon as they were aware of the fraud that they would be pursuing of a claim against the vendor. What argument did the purchasers in Redican make that the transaction was not complete because a cheque was involved? They argued that the cheque was only a conditional payment, and therefore the contract had not been completed (or, another way of saying the same thing, it had not been executed or fully performed). The Supreme Court of Canada rejected this argument. The understanding in conveyancing practice was that as soon as the cheque was received in exchange for the transfer documents, the contract was complete. In Heilbut, Symons, what secondary principles did Lord Moulton refer to? One, from the Cave v Coleman case, was that a representation made in the course of dealing (that is, negotiations) is a warranty/term, and the other, from the De Lassalle case, was that if a knowledgeable vendor asserts a fact about which the purchaser if ignorant that amounts to a term. Both of these tests were rejected: the first because it was “too sweeping” (it would make almost all pre-contractual representations terms), and the second because it was not otherwise supported by case law. At most, these “principles” are factors to be considered along with all the other evidence in determining whether the representation was intended to be a term. How was the broad intention test applied to the facts in Heilbut, Symons? The court concluded that after considering all the evidence it had not been proved that the statement made by Heilbut, Symons (that the company was rubber company thereby implying that it had an adequate supply of rubber trees) was intended to be a warranty or term of the contract. If a court were to use the collateral contract analysis for pre- contract statements, what would the consideration be for the representation? The consideration would be the purchaser’s entering into the main contract. Assume that a claim for mere misrepresentation in Heilbut, Symons would have been possible. Would the amount of money the plaintiff would receive under the rescission remedy be the same as if a claim for damages for breach of contract were successful? Not necessarily. If a claim for mere misrepresentation and rescission were successful, then all the plaintiff would receive would be his money back. If a claim for damages were successful, then the plaintiff could sue for his full expectation loss, which could include any profits he would have made based on the increase in value of the shares (had the representation been true). In Dick Bentley: a) Did Lord Denning set out a secondary principle for determining intention, and if so how did he apply it? Yes, on page 382 in the second paragraph, he stated that if a representation is made in the course of dealings for a contract for the very purpose of inducing the other party to act on it and it actually induces him to act on it by entering into the contract, that is prima facie ground for inferring that the representation was intended as a warranty. This sounds very similar to the course of dealing secondary principle the House of Lords rejected in Heilbut, Symons (Lord Denning didn’t always follow the House of Lords). Lord Denning applied the principle by finding that the vendor’s misrepresentation—that the car only had 20,000 miles on it since it had been fitted with a new engine and gearbox—was intended to be a warranty. The plaintiffs were therefore successful in suing for damages for its breach. b) If you conclude that Lord Denning in Dick Bentley did set out a secondary principle, how is it different from the reliance test used in misrepresentation/rescission claims? It appears to be the same, or very similar, to the inducement/reliance test used to prove a claim for rescission. c) Finally, if you conclude there is no difference, what logical inconsistency arises in using the same test in these two different contexts? The logical inconsistency that arises is that by proving reliance you have just proved that the statement is a warranty (that is, a term of the contract). But if the representation is a term it can’t also be a mere misrepresentation (which is by definition something less than a term), and if it’s not a mere misrepresentation you wouldn’t be entitled to the remedy of rescission (rescission is available for mere misrepresentation, but not for breach of a term). Does this legislation significantly alter the common law and equitable rules relating to remedies for misrepresentation? Is it an improvement? It changes the rules in the context of consumer transactions, in that it is no longer necessary to distinguish between mere misrepresentations and terms. The remedies are the same for both if you can prove that the representation or conduct in questions amounts to a “deceptive act or practice.” Section 171 allows for damages to be claimed in Provincial Court and is the most commonly pursued remedy. Section 172(3)(a) allows for a restoration order (the equivalent of rescission) and must be brought in BC Supreme Court. However, the restoration of order is conditioned on the consumer also claiming for a declaration or injunction order against a supplier under section 172(1), in effect, requiring the consumer to take responsibility for enforcing the legislation before being entitled to a restoration order. This is an expensive and time-consuming undertaking, and most consumers do not pursue this order. It is cheaper and more effective not to use the legislation, despite the complexity of the common law and equitable rules in this area. So, overall, there is an argument this legislative in not an improvement. Parol Evidence Rule Questions In the Horse case, discussed on page 414, what document was the “contract” and what was the extrinsic evidence the defendants were relying on? The treaty (Treaty No. 6) was the contract, and the extrinsic evidence was the record of the negotiations. The defendants had been charged with illegal hunting. The treaty forbade hunting on privately owned land, but in negotiations Saskatchewan’s Indigenous people were told they could hunt as before without limitation. The Supreme Court of Canada held that the parol evidence rule prevented any modifications to the treaty, and the evidence of the negotiations couldn’t be used to interpret the treaty because its terms were clear. Such as restrictive approach is no longer followed when applying and interpreting treaty documents – extrinsic historical and cultural evidence is now admissible. In the sale-of-car example described on page 413, what actions could Jones bring against Smith for the oral fraudulent misrepresentation about the mileage (kilometerage?) on the car? Jones could sue for mere misrepresentation and rescission, or for damages in tort, based on the Smith’s oral statement. In neither case would proving this statement offend the parol evidence rule, because Jones would not be suing to modify the contract and give contractual effect to the statement. In Evans, Roskill LJ’ s first holding (long paragraph on page 429) was that the written document was not intended to be the whole contract, and that the contract was partly in writing and partly oral. Therefore, evidence of the oral promise to ship the container under deck was admissible without offending the parol evidence rule. Is there a problem with this holding in light of the written terms of the contract? Yes, Roskill LJ doesn’t address the obvious conflict between the oral representation and the terms in the written document. For example, clause 4 states that: Subject to express instructions in writing given by the customer the company reserves to itself complete freedom in respect of means route and procedure to be followed in the handling and transportation of the goods In Gallen, Lambert JA made eight comments about the parol evidence rule, and decided that the rule, on the facts, did not prevent proof of the oral assurance that the buckwheat crop would not be smothered by weeds (it was). What was main basis of his decision? The main basis of his decision was that there was no contradiction between the oral representation and clause 23. Collateral oral contracts can be proved if they do not contradict the main written contract. Here, the oral representation was a specific warranty that buckwheat would not be smothered by weeds, and clause 23 was a general exclusion of responsibility for matters relating to the productiveness or yield of the crop based on such things as soil conditions or farming methods. Can you spot the spelling mistake in this legislation? Parole in the legislation should be spelled parol. Parole is what you get with early release from your prison term. Representations and Terms Questions In Hong Kong Fir, how did Lord Diplock define conditions, warranties, and third category (aka intermediate or innominate) terms? Lord Diplock defined conditions as terms where every breach of such an undertaking must give rise to an event which will deprive the party not in default of substantially the whole benefit which it was intended that he should obtain from the contract. These are terms where you can predict in advance that every breach will be serious. For breach of these terms, the innocent party may elect to treat the contract is over, and, as well, claim damages. He defined warranties as terms where no breach can give rise to an event which will deprive the party not in default of substantially the whole benefit which it was intended that he should obtain from the contract. These are terms where you can predict in advance that no breach will be serious. The only remedy available for the breach of a warranty, as technically defined here, is damages. He defined intermediate/innominate terms as undertaking where all that can be predicated is that some breaches will, and others will not, give rise to an event which will deprive the party not in default of substantially the whole benefit which it was intended that he should obtain from the contract; and the legal consequences of a breach of such an undertaking, unless provided for expressly in the contract, depend on the nature of the event to which the breach gives rise and do not follow automatically from a prior classification of the undertaking as a “condition” or a “warranty”. These are terms where you cannot predict in advance how serious their breach will be. They are wait-and-see terms. If the breach turns out to be serious, then you can treat it as if it were a breach of condition. If the breach is not serious, then you have to treat the breach as if it were a breach of warranty. Note as well that Lord Diplock made it clear that these definitions are subject to the express intentions of the parties. For example, the parties could expressly define any term as a condition, no matter how inconsequential it might seem to the average person. In Hong Kong Fir, in which category did cl. 1, the “seaworthiness” provision, belong, and what were the consequences of its breach? Clause 1 was held to be a third category term, and the breach was held to be not serious (it didn’t deprive the charterer of substantially the whole benefit of the contract). Therefore, the charterer was only entitled to damages and was not entitled to repudiate/terminate the contract. In surveying the existing case law where good faith obligations had already been recognized, Cromwell J, writing for the Court in Bhasin, referred to a number of different situations and relationships. Name three of them. Any three of 1. where the parties must cooperate in order to achieve the objects of the contract; 2. where one party exercises a discretionary power under the contract; 3. where one party tries to use a contractual power to evade contractual duties; 4. in employment contracts, an employer’s obligation to exercise good faith in the manner of termination of employees; 5. an insurer’s obligation to deal with claims fairly, both with respect to the manner in which it investigates and assesses the claim and to the decision whether or not to pay it; and 6. in the tendering context, the owner’s good faith obligation, in the sense of fair dealing, when considering bids. In Fairbanks Soap, why was the contractor unsuccessful in claiming that he had substantially completed the project when the remaining cost of completion was only around $600 (on a $9,800 project)? Because while the cost was low the remaining work required specialized engineering skill and knowledge. The assessment of whether a job has been substantially completed is not a simple cost test, but requires a holistic examination of all relevant factors. Why is it difficult to prove quantum meruit claims where improvements to land are involved? Because taking advantage of or benefiting from the work is only good evidence of an implied new contract if there is a choice whether or not to do so. The courts generally find that when it comes to unfinished work on land, an owner who completes and uses the work has no choice; no one should be forced to leave unfinished work on their property. Affirmation means that the party seeking relief is aware of the facts which give rise to the right to rescind and that, by words or conduct, he has decided not to exercise that right. Typical examples of affirmation include the situation in which the buyer of goods, after becoming aware of the falsity of a misrepresentation, continues to use them. Similarly lapse of time may be taken as evidence of affirmation as may an agreement to accept a cure of defects in the subject matter of the contract. https://www.studocu.com/en-ca/document/university-of-windsor/contract-law/summarycontracts-compiled-notes/585340 https://docplayer.net/40814151-Cases-and-notes-summary-for-contract-law.html https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/7386604/contracts-can-whole-year-ubc-lawstudents https://www.studocu.com/en-ca/document/university-of-alberta/contract-law/final-examframework/9570297 https://www.studystack.com/flashcard-1199949