ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

1

Title of Assignment

Implementing Flexible Curriculum: The potential opportunities and challenges in

integrating online learning into teaching and learning post-COVID

Module Name

DED 623: Curriculum and Innovation: Theory and Practice

Module Coordinator

Dr. Christopher Hill

Student ID

2013121113

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

2

Table of Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3

Context ............................................................................................................................................ 4

Literature Review and Theoratical Approach to Flexible Curriculum ........................................... 5

Flexible Learning ........................................................................................................................ 5

Curriculum flexibility ................................................................................................................. 6

Asynchronous learning as an approach to remote teaching ........................................................ 7

Blended curriculum and blended learning .................................................................................. 8

Methodologies and approaches to implementation of a Blended Curriculum ................................ 9

Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 12

Data collection procedure ............................................................................................................. 12

Results and Discussion ................................................................................................................. 12

Descriptive statistics ................................................................................................................. 12

Discussion ................................................................................................................................. 14

Conclusion and recommendations ................................................................................................ 17

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

3

Introduction

Over the last five decades, the world has seen a drastic growth in education at all academic levels.

Today, COVID-19 is the great challenge impeding growth in educational systems hence trying to

undo all the previous achievements (Mahaye 2020). This global pandemic has influenced

education policies in many countries to the extent that governments have forced institutions to do

away with face to face learning to virtual education and online teaching. Unfortunately, key

education stakeholders such as institutional heads, teachers, and government officials have not

attained sufficient guidance on how to address this dilemma. There is still a challenge of the

knowledge gap on how educational institutions can implement asynchronous learning/ flexible

teaching and what preparations would be appropriate to address the needs of learners at various

levels in different fields of study (Czerniewicz, Trotter & Haupt 2019). One of the recommended

preparations is the adoption of the blended curriculum, but how can this be implemented in flexible

ways to improve students' learning trajectories during and after this pandemic?

This research paper presents insights on the various processes that help schools to realize

flexibility in blended curriculum implementation. Flexibility in the curriculum can be

contextualized in terms of accessibility and adaptability of the curriculum to the various

capabilities and needs of the students. The blended curriculum aims at realizing flexibility in

learning by combing online and face to face components (Khan, Shaik, Ali & Bebi, 2012). Several

educational institutions are designing and implementing blended curricula to increase the

enrolment of students and meet the needs of diverse students' graduation portfolios. To promote

continuous learning during the COVID crisis, schools have to design a curriculum that allows

enables remote learning. The response to these initiatives varies across different countries and

jurisdictions (Mahaye 2020). Some countries have predetermined national curricula while others

have given teachers discretion to select the teaching program content. Much as it is imperative to

direct students' learning to the flexible curriculum and examinations/assessments, it is also

important to protect students' interest in learning by focusing on the diverse needs of learners in

both historical and global contexts.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

4

Context

This research also explores the conditions that can promote or affect the realization of curriculum

flexibility. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten educators to determine what

defining curricular flexibility in schools, the level of success is obtained by schools in utilizing

flexible curriculum approaches to blended learning, which predicts the effectiveness,

opportunities, and challenges of delivering flexible curriculum during and after the COVID crisis.

The paper is segmented into three major sections. Section one is the introduction, which explains

the rationale for conducting this research. The second section is the literature review and the

theoretical approach to blended curriculum based on the existing research. The third section is the

discussions section, which explains the obtained research findings in relation to the existing

literature, focused on the opportunities and challenges of implementing blended curriculum as one

way of ensuring flexibility in teaching.

The study was conducted by collecting responses from participants from the various educational

institutions in the United Arab Emirates and Middle East countries. The institutions offer various

programs of higher education, which prepare students for further studies and fieldwork. The

school also has various graduation portfolios. Due to the outbreak of COVID, students were

dispersed to their homes. To facilitate teaching, it was determined that the schools should initiate

online teaching and learning in the time of social distancing to continue students’ educational

activities and implement a flexible blended curriculum to address the needs of the students

(Mahaye 2020). The design of this curriculum was developed on a framework that includes

alteration between online and face to face learning, organization of weekly lessons and creation of

digital platforms to allow students to share the corresponding teaching materials. The blend also

includes a source of curriculum materials in online lessons and electronic learning environments

through software connections hence allowing synchronous communication to thrive (Cheong,

2013). Teacher educators were given discretionary powers to fill the blended structure to meet the

needs of their teaching courses by deciding on what should be done online and on face to face.

This implies that different uses use different blended structures for their curriculum teaching,

which creates the need to examine the flexibility of the schools' formal curriculum. Following are

the questions developed to collect responses.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

5

Research questions

I.

II.

What best defines curricular flexibility in the school?

How successfully is the school using flexible approaches to the curriculum and

assessments to engage students who need additional support?

III.

How does curricular flexibility enable students to learn 21st-Century Skills?

IV.

Should online teaching be considered as an alternative approach to teaching one on

one in schools?

V.

Is the school curriculum flexible enough to deliver online during COVID-19

without any drastic change?

VI.

Have schools made changes to the content and assessment process to fit into the

situation?

VII.

VIII.

How does the school assess students' learning when teaching online?

What are the potential opportunities and challenges in integrating online learning

into teaching and learning post-COVID?

Literature Review and Theoratical Approach to Flexible Curriculum

Flexible Learning

In teaching and learning, flexibility is the ability of the educational environment to offer a wide

range of choices and customize the course to meet the diverse learning needs and expectations of

individual students (Jonker, März, & Voogt, 2020). Because of the mushrooming dynamics such

as pandemics, natural hazards, wars, and political insurgencies, among others, schools ought to

provide the possibility of making learning choices to students. Such choices of earning should

cover a wide range of aspects, including instructional approach, course content, class times, and

communication medium, learning resources, technology use, and learning location, requirements

for entry, and completion dates, among others. The current technological advancements have led

to the development of ICT systems that allows the integration of new learning models, which has

created more opportunities for the proliferation of flexible learning(Singh & Thurman, 2019).

One of the opportunities for flexible learning is open learning, which focuses on making learners

more independent and self-determined as teachers become facilitators than instructors.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

6

Flexibility-oriented practices are based on the learner-centered philosophy, which is the foundation

theory. The creation of flexible learning environments allows the elimination of barriers to attend

classrooms in a given educational context and allows instructors and students to exchange

knowledge in a two-way approach (Ryan & Tilbury, 2013; Gordon, 2014). Flexible learning has

been extended further to address issues of flexible pedagogy beyond simple syllabus coverage.

According to Gardon (2014), flexible pedagogy is an attribute of learner-centered approach, which

gives educators a wide range of choices from the study dimensions such as learning time and

location, learning activities, support for learners and teachers, learning and teaching resources, as

well as flexible instructional strategies. These choices have made learning and teaching more

flexible compared to ancient fixed teaching and learning approaches, which has promoted

effective, engaged, and easy learning.

There are several characteristics that make learning flexible in both classroom and online settings.

First of all, learners should be provided with a wide range of choices and empowered to take

learning responsibilities for purposes of understanding the curriculum content (Jonker, März, &

Voogt, 2020). This means that learns should be able to regulate themselves in terms of making

adjustments, self-monitoring, goal setting, and making rational decisions and necessary

adjustments. All these and capabilities enable active learning to make learning more effective and

engaging rather than instructive. The second characteristic of flexible learning is that it applies

the constructivist approach, which is learner-centered, by allowing changes in the teaching process

whereby the learner has to take the learning responsibilities instead of the teacher taking such

responsibilities (Jonker, März, & Voogt, 2020).

Curriculum flexibility

Today, learning institutions are enrolling studies from diverse backgrounds in terms of cultural

background, domicile, age, professional and personal experiences, prior education, digital literacy,

and learning approaches (Severiens et al., 2014). The increasing diversity requires a flexible

curriculum that addresses and adapts to the different capabilities and needs of the learners (Rao &

Meo 2016). Flexible curricula provide more opportunities for learners to regulate their learning

environment and learning/study processes. According to Cheong (2013), curriculum flexibility

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

7

requires a proper understanding of the available choices of learning and how those choices affect

an individual's learning. However, Tucker and Morris (2011) noted that the degrees of flexibility

vary with different continuums where the curriculum can be positioned. A curriculum can be

flexible in terms of its details, how, when, and where it is being implemented. According to

Carlsen et al. (2016), curriculum flexibility based on when and where aspects of learning are the

requirement for inclusion of all learners in the educational framework irrespective of their diverse

backgrounds. In fact, a flexible curriculum that enables learners to decide on what, when, and

where they should learn is fascinating to both the students at remote locations and non-traditional

students. The extent to which the curriculum is adoptable or accessible is the adaptability or

accessibility dimension of contextualizing the curriculum. Flexibility in the perception of learning

is important since students have diverse learning challenges that influence learning and teaching

processes.

Asynchronous learning as an approach to remote teaching

The outbreak of COVID 19 is one of the circumstances that have created a dilemma on how

learning institutions can maintain contacts with parents and students. This has created a need to

ramp up their ability to conduct remote teaching, inform and ensure contact with learners

(Czerniewicz, Trotter, & Haupt 2019). Teachers need to learn new technology and pedagogy to

give this reassurance to the learners that they are able to conduct remote teaching (Jonker, März,

& Voogt 2020). To achieve remote teaching among those teachers who are used to real-time

classroom teaching is adopting asynchronous learning. For most teaching and learning aspects,

there is no simultaneous communication between the teacher and the students. Asynchronous

learning creates flexibility for teachers in preparing teaching and learning materials and helps

learners to maneuver the demands for study against the demands at home (Smits & Voogt 2017).

Asynchronous learning is appropriate in digital formats (Khan et al. 2012). Teachers have

offloaded the burden of delivering the learning materials in a fixed time frame because they can

post such material online for access by students on-demand and enable the learners to engage with

e-mails, blogs, and wikis to flexibly meet their schedules. The other benefit of asynchronous

learning is that it helps teachers to make the periodic analysis of student participation and make an

online appointment for learners with specific questions and learning needs.

According to

Czerniewicz, Trotter and Haupt (2019), video lessons are easier to prepare and effective to deliver

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

8

since they are usually short, taking not more than 30 minutes. Education institutions offering

online courses should design optimized approaches to asynchronous learning that balance

effectiveness and accessibility.

Blended curriculum and blended learning

The blended curriculum is the curriculum that deliberately mixes both face to face and digital

education to support and stimulate learning to realize flexibility in teaching and learning (Boelens

et al., 2017). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many educational institutions may be forced to

embrace blended education through the reformation of the curriculum, learning activities, and

teaching courses. The blended curriculum design can be placed on various continuums depending

on the appropriateness of the context where learning and teaching can be accomplished either in

face to face teaching with face to face curricula or online /digital environment with online

curricular (Graham et al. 2013; Czerniewicz, Trotter & Haupt 2019). Other determinant factors

include the functions of online and face to face parts, who control the curricula blend, i.e., the

students, teacher or the designer; the sequence of online and face to face parts (Boelens et al. 2017).

The digital environment is enriched with many flexible options that help teachers to deliver

knowledge without involving face to face contact. According to Carlsen et al. (2016), ICTs play a

significant role in helping schools realize flexibility in curriculum implementation because of the

provide alternatives and make choices from a variety of manageable and realizable educational

interventions hence bridge the time and distance. In regard to flexible curriculum, the digital

element of the blended curriculum helps the teachers to present the content through different means

at different levels using a variety of alternative and choices such as learning materials and activities

hence enabling educational institutions to realize pedagogical and programmatic responsiveness

to the learning needs of students. Digital platforms bring education to learners to distant locations

and help learners to have an opportunity to study at their convenient time hence promoting learning

inclusion to all students. Flexibility is connected to various underlying pedagogies that can be

adopted in 21st-century teaching and teaching (Nikolov et al. 2018; Jonker, März & Voogt, 2020).

Blended learning is appropriate for the implementation and adoption of the learner-centered

teaching approaches whereby learners with their needs are prioritized when making decisions

regarding the learning and teaching processes. The teacher becomes a coach instead of being the

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

9

center of student interactions. Blended learning integrates ICT into the learning and teaching

environment to combine both online and face to face learning and teaching. It is an academic

setting in learning and teaching situations where there is a combination of the learning approaches,

models of teaching, and various delivery platforms (Smits & Voogt, 2017). Schools should adopt

blended learning as the outcome of applying the systematic and strategic approach to the

integration of technology to facilitate and stimulate interaction between students and teachers.

Blended learning requires three major aspects, namely interactive traditional teaching approaches,

instructor based training approaches, technologically enabled, and multiple content delivery mode

(Khan,et al. 2012). All these learning aspects are facilitated by the instructor or the teacher.

According to Chlup and Coryell (2017), blended learning combines cooperative/live learning,

virtual learning, and traditional learning. It also combines unstructured and structured methods of

learning and mixes asynchronous learning or synchronous learning with online formats of learning.

In all models, there use of two different instruction media. According to Khan et al. (2012), blended

learning requires improvement on the existing pedagogical tendencies that apply a variety of

teaching models and approaches assisted by technology. It cannot thrive with the presence of both

the students and the teachers. It involves the application of different teaching methods, and

technology offers the elements of teaching control such as pace, time, and content delivery and

instruction platforms.

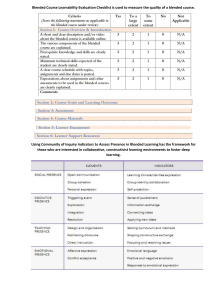

Methodologies and approaches to implementation of a Blended Curriculum

The increasing growth of student enrolment stimulates the need for more robust and effective

teaching approaches to revolutionize education systems in schools by focusing on trends in the

evolution of ICT. The proliferation of ICT increase across the world, global education systems

should adapt new technologies to transform the curriculum and enable it to meet the demands of

the 21st century (Aguilar 2012; Huang et al. 2013). Education practices need to be aligned with

technology to improve the quality and effectiveness of education. The use of a blended curriculum

in education institutions requires a clear framework to improve its effectiveness and efficiency.

The framework determines what should be taught, how it benefits the learners, and the potentials

offered by the curriculum implement to learning and teaching processes (Kintu et al., 2017).

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

10

In Kintu, Zhu, and Kagambe (2017), the authors explain how robots can be used for the

implementation of the blended curriculum in elementary schools. However, some countries have

not to be embraced in different countries. There are quality dimensions through which robotic

education can be contextualized in the facilitation of blended learning. The CFA six-factor model

explains five quality dimensions that allow the applicability of robotic education, namely; teaching

methods, cognitive functions, social interactions, principal features, and characteristics of the

pupils as well as the learning content (Bijeikiene, Rasinskiene & Zutkiens, 2011). Schools have

a duty to select which dimensions are useful for teaching, learning, and curriculum administration.

Technology adoption in learning and teaching helps departments and instructors to come up with

flexible learning approaches.

According to Gordon (2014), there is a variety of web tools to assist learners in developing content

and interacting with their colleagues using social networks, wikis, and blogs. In addition, the

existing communication mediums, e.g., instant messages and e-mail applications improve the

convenience of administrators and teachers in the implementation of the blended curriculum.

Schools also ought to provide evaluation and assessment of learning quality and the effectiveness

of the academic and teaching programs to determine whether they are resonating with the

requirements of flexible teaching/learning, there are various methods of conducting such quality

assessments such as standardized tests, peer assessments, team projects, research papers, and

presentations(Jonker, März, & Voogt 2020). E-portfolios provide more flexibility for learners to

assess themselves and update evidence of their achievements and academic developments.

Flexible curriculum implementation requires flexible timing and assessment delivery channel to

conduct both human managed assessments and computer-based tests such as adaptive and online

tests. Schools can also utilize learning analytics to provide flexible learning (Jonker, März & Voogt

2020). These analytics collect the learning traces of students within a system of learning and

generate dashboards, reports, and other real-time assessments.

Blended curriculum implementation requires specialized services and supports that should be

given to both the instructors and students. The place and the time to gather such support and the

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

11

approaches to get such support should also be flexible enough. According to Gordon (2014),

students can get digital support through online meetings, face-face interactions with

teachers/tutors, help desks, video-based real-time interaction tools, group help sessions, and online

meetings with their tutors, among other methods. Because of diversity in the languages and other

cultural backgrounds, schools must allow learners to specify the language of communication or

the language used on the learning materials to support international students.

Today, the

proliferation of intelligent learning technologies is enabling schools to provide personalized

student support based on the learning needs and characteristics of the student, such as personal

preferences, special needs, learning performance, among others (Mahaye 2020). In the context of

computing education, blended learning is facilitated by modern technology that provides rigors

and depth analysis of the faculty to develop models that promote active learning and increase

student participation.

In brief, higher education is experiencing significant changes because of the current Pandemics

amidst the advancement in technology and the use of ICTs. E-learning and mobile learning are

facilitating the learning and teaching experience with the use of modern technologies and media

channels. One of the outcomes of ICT-based learning systems is blended learning, which requires

the use of a flexible/blended curriculum. The application of blended learning approaches requires

the reformation of the existing traditional learning approaches, and integration of technologysupported learning approaches hence offsetting the consequences of traditional teaching

methodologies (Khan et al. 2012).

In terms of assessment, the flexible curriculum requires that teachers should provide immediate

feedback to the learners regarding their performance. This can be attained by the use of the latest

technologies, such as Zoom, in combination with various assessment techniques (Bakir 2013).

Assessments help to examine how the teachers are implementing a blended curriculum and how

students understand the curriculum/course content, but it requires innovative and creative methods.

This above literature presents the opportunities, challenges, and requirements of implementing a

blended/flexible curriculum in 21st-century learning and teaching.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

12

Methodology

During this COVID-19 outbreak, it is evident that the nature of learning spaces are changing

drastically. The situation becomes challenging for many educational institutions, and keeping

consistency in instructions is becoming a great issue (Mahaye 2020). On the other hand, for many,

it has been an opportunity to employ technology as an instructional tool, and enrich their IT skills

to enhance teaching effectiveness. A qualitative approach was employed to explore the elements

of flexible learning and how effective do we see the use of flexibility in normal times and times

like these. The 15 minutes-survey was conducted to collect the responses of teachers about the

extent of flexibility in the institution's curriculum and assessment processes. Most of the questions

were open ended to secure maximum subjective content and narrative descriptions. Flexibility was

examined to determine the effectiveness and rigorousness of the curriculum that allows educators

to support students in meeting their individual needs and facilitate developing life skills.

Data collection procedure

A consent form was sent to the respondents to obtain their prior informed consent regarding their

participation in the study. After gaining consent, a link to the online survey was sent to the

participants, which they were able to fill and submit their responses. Teachers were randomly

sampled from various schools around the Middle East. After obtaining ethical clearance from the

university faculty, respondents accepted to respond to the survey. Potential respondents were

approached by sending e-mails to teachers from learning institutions via their departments. The

sample was skewed towards respondents who share the same interest in blended curriculum

delivery. A sum of thirty-three teachers from different faculty departments participated in the

survey.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics

Results indicate that out of the 33 teachers, 27(82%) teachers were from UAE schools, while 18%

of teachers were from other countries. In terms of work experience, it was found that 24% of

teachers had less than five years' experience, while 39% had a wider teaching experience ranging

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

13

from 5 to 12 years. The most commonly taught curricula were CCSS (48%), British (24%), IB

(3%), and other curricula (24%). The majority of the teachers had taught 6th to 10th grades, while

Pre-K grade was the least taught grade. Details of all the responses to the survey have been

presented in the Appendix section of this paper. The tables below show the demographic details

of the survey.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

14

Social distancing has been enforced in more than 120 countries across the world as a preventive

measure against the COVID-19 pandemic. This has resulted in the temporary closure of learning

institutions both locally and regionally. Flexible curricula have been implemented by different

governments to avoid total curriculum disruption. Flexible curriculum is being adopted through

technology-based pedagogy to facilitate the learning and dissemination of learning materials to

students who are staying home. This paper was aimed at examining the effectiveness, challenges,

and opportunities of implementing a blended curriculum to allow flexible learning in this pandemic

era.

When participants were asked about what best defines curricular flexibility in delivering

instruction and assessing students understanding, one of the participants indicated that

"There are several processes we can apply depending on the program, level of student and

urgency...such at altering planning topics covered, scheduling, duration of instruction, assessment

as to cut down weigh, or limit assessment components, or decrease percentages, use of distance

and online learning regarding the type of functions used, duration, attendance-participation.”

Another respondent indicated that:

"Students should be assessed often to check their understanding via exit card; formative

assessment helps the teacher define his flexibility and support students understanding for the

subject taught."

These responses imply that implementation of a flexible curriculum requires rigorous curriculum

reform and transformation in various aspects such as topics covered, scheduling, duration of

instruction, assessment as to cut down weigh, or limit assessment components, or decrease

percentages, use of distance and online learning regarding the type of functions used.

Discussion

For the comprehension of study findings, it is imperative to understand the perceptions of teachers

regarding the flexibility of a blended curriculum with respect to the existing research. There are

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

15

diverse perceptions that emerged from various questions about curriculum flexibility. Teachers

were asked about what flexible approaches are being used by schools to deliver the curriculum and

conduct assessments in their school and engage students who need additional support. Some

teachers indicated that their schools are utilizing their inclusion department during assessments for

those who have difficulties in reading differentiated assessment while other respondents indicated

that they are now working on backward curriculum design to identify the gaps through

international and internal assessments, then develop a robust curriculum to overcome such

weaknesses (Mahaye 2020).

Flexible curriculum is also being implemented by being flexible with learners in terms of

instruction time, quality of questions, continuous follow up and encouragement by assessing them

on the spot and one by one in a way that suits each one potential and ability. These responses imply

that flexibility in the blended curriculum is perceived by schools in terms of adapting to the

student's preferences and the varied needs of the schools. No respondent contextualized flexible

curriculum implementation in the aspect of promoting distance learning. In fact, results indicate

that when participants were asked whether they think online teaching is more flexible than one on

one teaching, only 30% believed that online teaching is flexible in facilitating 21st-century teaching

while the majority (69%) were either not sure or could not believe in the same school of thought.

This explains the extent to which schools are adopting technology and online tools to facilitate

flexible learning in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results also indicate that majority of the participants (76%) believed that their curriculum was not

flexible enough to deliver online during COVID-19 without making minor changes to their lesson

plans. These findings imply that blended curriculum can only be implemented in a well digitally

developed society. Rural schools lack basic technology infrastructure and amenities to facilitate a

flexible curriculum; hence they may not benefit from the program. According to Jonker, März,

and Voogt (2020), all places should have digital equipment to ensure that there is equitable assess

to technology-based learning. Technology infrastructure is a precondition for the enactment and

implementation of flexible teaching and learning using technology-based approaches.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

16

Regarding student assessment, it was found that all respondents indicate that they use mobile

applications and web tools such as Quizzes during live sessions, Edmodo app, Nearpod activities,

Classkick, Mentimeter to send feedback on reports and other research components. However, it

was found that online teaching is affected by several challenges, including parent's refusal to take

online learning seriously; emotional, financial, economic, and social challenges affecting both

teachers and learners, difficulty in conducting science experiments, failure to keep all students on

task all the time.

According to Jonker, März, and Voogt, (2020), the conditions that lead to the success of flexible

curriculum implementation are either teacher-related, context-related or student-related

conditions. The attitude of the teachers towards curriculum flexibility can either hinder or enable

its implementation. Secondly, the challenge of lack of skills among teachers' especially digital

skills, pedagogical skills, and curriculum design skills, can influence the success and effectiveness

of the adopted blended curriculum flexibility.

Context-related conditions such as time, school rules and regulations, and availability of teaching

materials can also determine the flexibility and effectiveness of the blended curriculum. Some

teachers may not have adequate time to develop curriculum materials and redesign their courses

and translate them into a blended form. This means that more time is required to prepare digital

materials and online lessons to improve the flexibility of the curriculum. The availability of online

resources with flexible schedules creates more opportunities for students to use such online

resources at all times, unlike in circumstances when the materials have strict schedules. One of the

respondents indicated that

"…there is the limitation of the time because the curriculum load that should be covered in a very

short period of online sessions.

Parents' intervention in the learning process also hinders the flexibility of the blended curriculum

since some students have no devices, and some students do not show up to attend the sessions.

According to Czerniewicz, Trotter and Haupt (2019), student-related conditions such as student's

skills and attitudes can influence the flexibility of the blended curriculum. Lack of digital skills

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

17

can impede their adaptability to the blended curriculum, while passive student roles influenced by

a negative attitude towards learning hinder curriculum flexibility. According to Jonker, März, and

Voogt, (2020), flexible learning requires students to be able to make plans, structure their tasks,

study independently, and work according to their plans. Insufficient study skills is a common

challenge in young students, part-time students, and first-year learners.

The challenges and opportunities affecting the flexibility of the blended curriculum reflect the

success and effectiveness of curriculum implementation. According to Gaol & Hutagalung (2020),

a flexible blended curriculum requires a shared vision across all the stakeholders regarding the

rationale for its flexibility. This would improve the positive perceptions and attitudes of learners

and teachers towards the adoption of technologies and online learning materials. The changing

demands and fixed routines of both learners and students have found to limit the flexibility and

adaptability of the curriculum (Bakir 2013). There is an increasing concern the insufficient

instruction time, fixed daily routines diverting students from learning, and negative beliefs towards

blended learning (Tondeur et al. 2017; Mahaye 2020). According to Smits and Voogt (2017),

teachers need to exhibit a high level of professionalism when handling a blended curriculum and

delivering knowledge to develop self-efficacy and improve students' attitudes towards online

learning.

A high level of professionalism is needed when introducing and incorporating

technological changes in educational practices to improve the adaptability of the blended

curriculum.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study was aimed at capturing the perceptions of teachers towards curriculum flexibility in the

adopted blended curriculum used to facilitate learning in this COVID-19 pandemic. It presents

the underlying opportunities and challenges effective the implementation of a flexible blended

curriculum. Results indicate the level of flexibility in curriculum implementation is low since

many students are still struggling with various challenges regarding the adoption of modern

technologies to facilitate online teaching.

There are many student-related and teacher-related constraints regarding curriculum flexibility,

which require effective support and services as well as collaboration between schools, families,

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

18

governments, and enterprises to improve the quality and flexibility of blended learning. The

challenge of inadequate teaching and studying skills on the side of teachers and learners

respectively limits the flexibility of the blended curriculum. Many teachers still believe that online

learning may not transform flexible education in this pandemic era.

The timing and the location for online learning remains a big concern since most schools have not

ensured flexibility in the starting and finishing time for the course, the time of participating in the

course, the pace of study and the timing/schedule for student assessment. Schools need to specify

and ensure flexibility in the time for which students should study independently and the time for

which students should interact with colleagues and tutors.

Leaners should be given choices based on their educational challenges and preferences, for

example, studying over the weekends and evenings. The location where students can access

learning materials and conduct learning activities should be flexible enough with various options,

including public transport, homes, campus premises, websites, and mobile devices. Students

should be given an opportunity to determine the sequence and sections of the content to learn

depending on their size and scope of their course, forms of course orientation, pathways of

learning, and their desires, through the content modulation process. A self-inquiry course should

be conducted by the learning institutions to allow students to chose sections and topics of the

blended curriculum based on their learning needs, strengths, and personal interests.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

19

References

Boelens, R., De Wever, B. De. & Voet, M. (2017). Four key challenges to the design of blended

learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, vol. 22, pp. 1–18.

Bakir, D. A. (2013). Writing difficulties and new solutions: Blended learning as an approach to

improve writing abilities. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, vol. 3(9),

pp. 254–266.

Bijeikiene, V., Rasinskiene, S. & Zutkiens, L. (2011). Teachers' attitudes towards the use of

blended learning in the general English classroom. Studies about Languages, vol.18, pp. 122–

127.

Carlsen, A., Holmberg, C., Neghina, C. & Owusu-Boampong, A. (2016). Closing the gap:

Opportunities for distance education to benefit adult learners in higher education. Hamburg,

Germany: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning viewed 15 May 2020.

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243264

Cheong, K. (2013). Flexible learning: Dimensions and learner preferences. In Leveraging the

Power of Open and Distance Learning (ODL) for Building a Divergent Asia –Today's Solutions

and Tomorrow's Vision. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference of the Asian

Association of Open Universities pp. 1–8. Islamabad, Pakistan: Asian Association of Open

Universities

Coryell, J. E., & Chlup, D. T. (2017). Implementing e-learning components with adult English

language learners: Vital factors and lessons learned. Computer Assisted Language Learning,

20(3), 263–278.

Czerniewicz, L., Trotter, H. & Haupt, G. (2019). Online teaching in response to student protests

and campus shutdowns: academics' perspectives. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education, vol. 16 (1), pp. 43.

Daniel, S. J. (2020). Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects, pp.1-6

Gaol, F. L, & Hutagalung, F. (2020). The trends of blended learning in South East

Asia. Education and Information Technologies, vol. 25(2), pp. 659-663.

Gordon, N. A. (2014). Flexible Pedagogies: technology-enhanced learning. In The Higher

Education Academy.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

20

Graham, C. R., Woodfield, W. & Harrison, J. B. (2013). A framework for institutional adoption

and implementation of blended learning in higher education. Internet and Higher Education,

vol.18, pp. 4–14.

Jonker, H., März, V. & Voogt, J. (2020). Curriculum flexibility in a blended

curriculum. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology.

Khan, A. I., Shaik, M. S., Ali, A. M., & Bebi, C. V. (2012). Study of the blended learning

process in the education context. International Journal of Modern Education and Computer

Science, 4(9), 23.

Kintu, M., Zhu, C., & Kagambe, E. (2017). Blended learning effectiveness: The relationship

between student characteristics, design features, and outcomes. International Journal of

Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol.14(7)

Mahaye, N. E. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Education: Navigating Forward

the Pedagogy of Blended Learning. [online]. [Accessed 15 May 2020] Available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340899662

Nikolov, R., Lai, K. W., Sendova, E., & Jonker, H. (2018). Distance and flexible learning in the

twenty-first century. In J. M. Voogt, G. A. Knezek, R. Christensen, & K. Lai (Eds.), Second

handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education, pp. 1–16. Cham,

Switzerland: Springer International Handbooks of Education

Rao, K., & Meo, G. (2016). Using universal design for learning to design standards-based

lessons. SAGE Open, vol. 6(4), pp. 1–12.

Ryan, A., & Tilbury, D. (2013). Flexible Pedagogies: new pedagogical ideas. [online]. [Accessed

15 May 2020] Available at:

http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/detail/flexiblelearning/flexiblepedagogies/new_ped_idea

s/report?utm_medium=email&utm_source=The+Higher+Education+Academy&utm_ca

mpaign=4074096_140506&utmcontent=New-pedagogical-ideas-report

Severiens, S., Wolff, R., & Van Herpen, S. (2014). Teaching for diversity: a literature overview

and an analysis of the curriculum of a teacher training college. European Journal of Teacher

Education, vol. 37(3), pp. 295–311.

Singh, V., & Thurman, A. (2019). How Many Ways Can We Define Online Learning? A

Systematic Literature Review of Definitions of Online Learning (1988-2018). American Journal

of Distance Education vol. 33.(4), pp. 289-306.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

21

Smits, A. E. H. & Voogt, J. M. (2017). Elements of satisfactory online asynchronous teacher

behavior in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 33(2), 97114.

Tondeur, J., Van Braak, J., Ertmer, P. A. & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. (2017). Understanding the

relationship between teachers' pedagogical beliefs and technology use in education: A systematic

review of qualitative evidence. Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 65(3),

pp. 555–575.

Tucker, R. & Morris, G. (2011). Anytime, anywhere, anyplace: Articulating the meaning of

flexible delivery in built environment education. British Journal of Educational Technology, vol.

42 (6), 904–915.

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

Appendices

Appendix 1: Screen Shots of Survey

(Questions)

22

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

23

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

Appendix 2: Screenshots of participants’s responses

24

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

25

ATTAINING A FLEXIBLE CURRICULUM

26