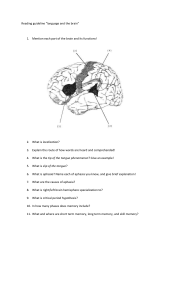

Language and Communication Skills (SPED 3164) 2. Disorders of Communication and Dysphagia 2.1. Disorders of Speech: Dysfluency, Dysphasia, Articulation and Phonological Disorders, Cleft Lip and Palate, Voice Disorders 2.2. Disorder of Speech of Neurogenic Origin: Dyspraxia, Dysarthria 2.3. Disorders of Language: Language Delay and Deviance, Specific Language Impairment 2.4. Disorders of Language of Neurogenic Origin: Childhood Aphasia, Aphasia, Dementia, TBI 2.5. Feeding and Swallowing Disorders Disorders of Speech Speech disorders affect the way a person talks. A person with a speech disorder usually knows exactly what they want to say and what is appropriate for the situation, but they have trouble producing the sounds to communicate it effectively. Speech disorders include a variety of conditions that affect children and adults alike. They can range from trouble pronouncing a specific letter or sound to the inability to produce any understandable speech. Some are the result of a physical deformity. Others are the result of damage to the speech mechanism (larynx, lips, teeth, tongue, and palate) caused by injury or diseases, such as cancer. Often the cause of a speech disorder is not known. Dysfluency: Dysfluency" is any break in fluent speech. Everyone has dysfluencies from time to time. "Stuttering" is speech that has more dysfluencies than is considered average. Dysfluency occurs when the normal flow and smooth delivery of speech are disrupted. Often, normal speech dysfluencies, such as silent pauses and non-lexical vocalizations (e.g., “uh” or “um”), can usefully add emphasis or draw attention to the content of upcoming utterances. In some people speech dysfluencies are pathological and interfere with speech communication to such an extent that a fluency disorder is diagnosed. The most commonly diagnosed fluency disorder is developmental stuttering, which is distinguished from acquired or neurogenic stuttering that is associated with brain disease or injury. Stuttering: Stuttering, also known as stammering, the most common fluency disorder, is an interruption in the flow of speaking characterized by repetitions (sounds, syllables, words, phrases), sound prolongations, blocks, interjections, and revisions, which may affect the rate and rhythm of speech. Stuttering is often accompanied by tension and anxiety, negative reactions, secondary behaviors, and avoidance of sounds, words, or speaking situations. Stuttering is often more severe when there is increased pressure to communicate (e.g., competing for talk time, giving a report at school, interviewing for a job). Social settings and high-stress environments can increase the likelihood that a person will stutter. Public speaking can be challenging for those who stutter. Symptoms of Stuttering: Stuttering is characterized by repeated words, sounds, or syllables and disruptions in the normal rate of speech. For example, a person may repeat the same consonant, like “K,” “G,” or “T.” They may have difficulty uttering certain sounds or starting a sentence. Signs and symptoms of stuttering include primary behaviors, such as • Monosyllabic whole-word repetitions (e.g., "why-why-why did he go there?") • Part-word or sound/syllable repetitions • Prolongations of sounds • Audible or silent blocking (filled or unfilled pauses in speech) • Words produced with an excess of physical tension or struggle Secondary, avoidance, or accessory behaviors that may impact overall communication include • Physical changes like facial tics, lip tremors, excessive eye blinking, and tension in the face and upper body, jaw tightening. • Frustration when attempting to communicate • Hesitation or pause before starting to speak • Refusal to speak • Distracting sounds (e.g., throat clearing, insertion of unintended sound) • Head movements (e.g., head nodding) • Movements of the extremities (e.g., leg tapping, fist clenching) • Sound or word avoidances (e.g., word substitution, insertion of unnecessary words, circumlocution) • Reduced verbal output due to speaking avoidance • Avoidance of social situations • Fillers to mask moments of stuttering. Interjections of extra sounds or words into sentences, such as “uh” or “um” Cluttering: Cluttering is a fluency disorder characterized by a rapid and/or irregular speaking rate, excessive disfluencies, and often other symptoms such as language or phonological errors and attention deficits. Cluttering involves excessive breaks in the normal flow of speech that seem to result from disorganized speech planning, talking too fast or in spurts, or simply being unsure of what one wants to say. In cluttering, the breakdowns in clarity that accompany a perceived rapid and/or irregular speech rate are often characterized by deletion and/or collapsing of syllables (e.g., "I wan watevision") and/or omission of word endings (e.g., "Turn the televise off"). The breakdowns in fluency are often characterized by more typical disfluencies (e.g., revisions, interjections) and/or pauses in places in sentences not expected grammatically, such as "I will go to the/store and buy apples". Signs and symptoms of cluttering include • Rapid and/or irregular speech rate; • Excessive coarticulation resulting in the collapsing and/or deletion of syllables and/or word endings; • Excessive disfluencies, which are usually of the more nonstuttering type (e.g., excessive revisions and/or use of filler words, such as "um"); • Pauses in places typically not expected syntactically; • Unusual prosody (often due to the atypical placement of pauses rather than a "pedantic" speaking style, as observed in many with ASD). Dysphasia: Dysphasia is an acquired disorder of spoken and written language (Greek: dys-, disordered; phasis, utterance). Dysphasia is a type of disorder where a person has difficulties comprehending language or speaking due to some type of damage in the parts of the brain responsible for communication. The symptoms of dysphasia vary based on the region of the brain that was damaged. There are different regions responsible for understanding language, speaking, reading, and writing, though typically they are found in the left side of the brain. Sometimes dysphasia is also referred to as aphasia, though generally it's considered a less severe version of aphasia. Types and Symptoms: There are different categories of dysphasia, separated based on their symptoms. Receptive Dysphasia: Receptive dysphasia results from lesions in Wernicke's area. Speech is fluent but makes little sense, consisting of word fragments, substitutions and neologisms (nonsense words). Since comprehension is affected, patients may be unaware of their own errors. People with receptive dysphasia have difficulties comprehending or receiving language. Imagine this form of dysphasia as feeling like people are always speaking to you in a foreign language. That would be so frustrating! Sometimes it can be easier to break sentences down into short, simple segments to prevent overwhelming the person with dysphasia, and it can also help to communicate in places without background noise or distractions. A person with receptive dysphasia may also have trouble reading out loud, whether the material was written by them or someone else, and they may forget information quickly. Expressive Dysphasia: Lesions involving Broca's area cause expressive dysphasia, which is nonfluent. Speech is hesitant, fragmented and ‘telegraphic’, with word-finding difficulty and a paucity of grammatical elements such as verbs and prepositions. Since comprehension is relatively spared, patients tend to become frustrated as they struggle to express themselves. People with expressive dysphasia have trouble expressing themselves in words. Some people with this form of dysphasia may not be able to verbally speak or communicate at all. Or, if they can speak, they may have trouble finding the right word they want to use or may accidentally use the opposite word of the one they’re looking for, or may not make sense at all, but not realize it. In addition to verbal communication, they may also struggle with reading and writing. Imagine having clear thoughts that you can’t effectively communicate to the outside world. In many cases, this is what having expressive dysphasia feels like. Mixed Dysphasia or Global Dysphasia: A combination of receptive and expressive features is called global dysphasia (or aphasia). Specific problems repeating sentences (e.g. ‘no ifs, ands or buts’) despite normal fluency and comprehension. People with mixed dysphasia suffer from the symptoms of both receptive and expressive dysphasia. They experience multiple complications understanding language and communicating successfully. They can have trouble receiving information and expressing information and it can affect both verbal and nonverbal communication. Articulation and Phonological Disorders: Speech sound disorders may be subdivided into two primary types, articulation disorders (also called phonetic disorders) and phonemic disorders (also called phonological disorders). Articulation Disorders: Articulation disorders (also called phonetic disorders, or simply "artic disorders" for short) are based on difficulty learning to physically produce the intended phonemes. Articulation disorders have to do with the main articulators which are the lips, teeth, alveolar ridge, hard palate, velum, glottis, and the tongue. If the disorder has anything to do with any of these articulators, then it is an articulation disorder. There are usually fewer errors than with a phonemic disorder, and distortions are more likely (though any omissions, additions, and substitutions may also be present). They are often treated by teaching the child how to physically produce the sound and having them practice its production until it (hopefully) becomes natural. Articulation disorders should not be confused with motor speech disorders, such as dysarthria (in which there is actual paralysis of the speech musculature) or developmental verbal dyspraxia (in which motor planning is severely impaired). In children with no associated condition, articulation disorders may be treatable with speech therapy. In individuals who have trouble articulating due to another condition, the prognosis of that condition will likely affect their progress in correcting their disordered articulation. Errors produced by children are typically classified into four categories: Omissions/Deletion: certain sounds are not produced. Entire syllables or classes of sounds may be deleted; e.g., fi' for fish or 'at for cat, “p_ay” for “play”; “_top” for “stop” Additions (or Epentheses/Commissions): insert an extra sound within a word. Examples: “buhlue” for “blue”; “doguh” for “dog” puh-lane for plane. Distortions: Sounds are changed slightly so that the intended sound may be recognized but sounds "wrong," or may not sound like any sound in the language or produce a sound in an unfamiliar manner. Examples: “cao” for “car”. Substitutions: One or more sounds are substituted for another or replacing one sound with another sound e.g., wabbit for rabbit or tow for cow. “wed” for “red”; “thun” for “sun”; “sot” for “sock”; “baf” for “bath” Phonological Disorder or Phonemic Disorders: In a phonemic disorder (also called a phonological disorders) the child is having trouble learning the sound system of the language, failing to recognize which sound-contrasts also contrast meaning. For example, the sounds /k/ and /t/ may not be recognized as having different meanings, so "call" and "tall" might be treated as homophones, both being pronounced as "tall." This is called phoneme collapse, and in some cases many sounds may all be represented by one e.g., /d/ might replace /t/, /k/, and /g/. As a result, the number of error sounds is often (though not always) greater than with articulation disorders and substitutions are usually the most common error. Or Phonological disorder is a type of speech disorder known as an articulation disorder. Children with phonological disorder do not use some or all the speech sounds expected for their age group. Phonological processes are patterns of sound errors that typically developing children use to simplify speech as they are learning to talk. A phonological disorder occurs when phonological processes persist beyond the age when most typically developing children have stopped using them or when the processes used are much different than what would be expected. Three types of phonological process Substitution Processes: when one class of sounds is replaced for another class of sounds. Syllable Structure Processes: sound changes that modify the syllabic structure of words. Assimilation Processes: one sound changes to become more like another sound, usually its neighboring sound. Cleft: A cleft is an abnormal opening or a fissure in an anatomical structure that is normally closed? Cleft Palate: Cleft palate is a condition in which the two plates of the skull that form the hard palate (roof of the mouth) are not completely joined. The soft palate is in these cases cleft as well. In most cases, cleft lip is also present. A cleft of the lip and/or palate is a congenital condition (present at birth due to either an inherited condition or something that occurred during the pregnancy). Types of Cleft Palate: Incomplete cleft palate: A cleft in the back of the mouth in the soft palate. Complete cleft palate: A cleft affecting the hard and soft parts of the palate. The mouth and nose cavities are exposed to each other. Submucous cleft palate: A cleft involving the hard and/or soft palate, covered by the mucous membrane lining the roof of the mouth. May be difficult to visualize. Complete Cleft Palate A "complete" cleft involves the entire primary and secondary palates. It extends from the uvula all the way into the alveolar ridge. It involves both the primary palate and secondary palate. A complete cleft palate can be unilateral or bilateral. If the cleft palate is bilateral, both sides may be complete, or one side may be complete, and the other side may be incomplete. Problems associated with Clef Palate Feeding: Feeding difficulties may occur in newborns with cleft lip and/or palate as the normal anatomy of the mouth is disrupted. Each baby is different in their ability to feed. In the presence of a cleft lip, the child may be unable to form a seal around the nipple of a bottle. Children with cleft palates have difficulty in generating suction because of the opening between the mouth and the nose. Speech: Children with unrepaired cleft palates will have speech difficulties. Normal speech is the goal of surgery. Many children will require speech therapy after the operation, and some may need a second procedure if speech difficulties persist. Cleft Lip: Cleft Lip: Cleft Lip is a visible gap or narrow opening on one or both sides of the upper lip that extend all the way to the base of the nose. When the upper lip is short and/or the premaxilla is protrusive, there may be bilabial incompetence, which is the inability to close the lips naturally at rest. If lip closure is difficult to accomplish at rest, it makes sense that there will also be difficulties with the production of bilabial sounds (/p/, /b/, /m/) with speech. As a result, the individual may compensate by producing these sounds with labiodental placement. This usually results in little auditory distortion but can be visually distracting to the listener. Voice: Voice is the ability to make sounds by vibrating the vocal cords. The buzzing sound made by the vibrating vocal cords is called the voice. Air from the lungs moves up through the windpipe (trachea) and between the vocal cords inside the voice box (larynx). The larynx is that part which forms the bulge in the front of our necks which is sometimes called the ‘Adam’s apple’. Inside the larynx are two strips of tissue called the vocal folds or vocal cords. As the air from the lungs pushes upwards and passes between the vocal folds they vibrate. They move backwards and forwards extremely quickly, releasing small puffs of air up into the throat. This creates a buzzing sound or voice. The air moving upwards through the throat can escape in one of two ways either through the oral cavity and out of the mouth, or through the nasal cavity and out of the nose. These cavities act like amplifiers, making the voice louder. If the vocal folds in the larynx did not vibrate normally, speech could only be produced as a whisper. There are three vocal characteristics: frequency, intensity, and phonatory quality. Effective voice production involves at least three things: 1. An appropriate breathing technique to provide the air support required to produce speech (diaphragmatic breathing) 2. Easy onset of the vibration of the vocal folds when speaking 3. Projecting the voice effortlessly without any strain or pushing Voice Disorders: Disorders of the voice involve problems with pitch, loudness, and quality. Pitch is the highness or lowness of a sound based on the frequency of the sound waves. Loudness is the volume (or amplitude) of the sound, while quality refers to the character or distinctive features of a sound. Many people who have normal speaking skills have great difficulty communicating when their vocal apparatus fails. This can occur if the nerves controlling the larynx are impaired because of an accident, a surgical procedure, a viral infection, or cancer. Abnormalities or changes in the vibratory system result in voice disorders. Voice disorders refer to breakdowns in the vibratory system. Breakdowns can affect any one or all the three subsystems of voice production. Air Pressure System: If the airflow source is weak or inefficient (making it difficult to push enough air out of lungs), the voice will be weak and hampered by shortness of breath. For example: Patients with asthma, lung cancer, emphysema and other lung conditions often find it difficult to speak loud or for long periods of time. Vibratory System: Any compromise or change to vocal fold vibration causes hoarseness and other voice symptoms. For example: Patients with stiffness in the vocal folds from swelling from a common cold develop hoarseness. For example: When focal folds cannot come perfectly together from partial nerve input loss, air leak occurs, and the voice is "breathy." Resonating System or Vocal Tract: A breakdown of the vocal tract can affect voice quality. For example, when nasal passageways are swollen and inflamed during the "common cold," the voice takes on a nasal quality. The result of impairment may be that one or more acoustic features are affected. Pitch Disorders: If the mass of the vocal folds (vocal cords) is increased, then the pitch of the voice will be too low. This could occur briefly, for example, because of a heavy cold in which there is an excessive buildup of mucous on the vocal folds. Growths on the vocal folds, such as vocal nodules or polyps, will lead to the pitch being too low over an extended period. If the vocal folds are held under too much tension, then the pitch will likely be too high. Similarly, variable tension in the vocal folds will lead to the pitch being unstable and possibly lead to pitch breaks. Monopitch: A voice that lacks normal inflectional variation and to change pitch voluntarily Inappropriate pitch: A voice judged to be outside the normal range of pitch for age and/or gender Pitch breaks: Sudden, uncontrolled changes in pitch Loudness Disorders: Forcing air from the lungs through the larynx with excessive pressure can lead to the voice sounding too loud. This is increased if the vocal folds are also held with excessive tension. Insufficient air pressure passing up through the larynx, together with weak vocal fold tension, creates a voice that is too quiet. Variable vocal fold tension and/or variable air pressure can lead to breaks in loudness. Monoloudness: A voice that lacks normal variations of intensity and the inability to change vocal loudness voluntarily Loudness Variation: Extreme variations in vocal intensity in which the voice is either too soft or too loud Resonance Disorder: Resonance refers to the way airflow for speech is shaped as it passes through the oral (mouth) and nasal (nose) cavities. During speech, the goal is to have good airflow through the mouth for all speech sounds except m, n, and ng. To direct air through the mouth, the soft palate (back part of the roof of the mouth) lifts and moves toward the back of the throat. This movement closes the velopharyngeal valve (opening between the mouth and the nose). See the diagram below. A resonance disorder occurs when there is an opening, inconsistent movement, or obstruction that changes the way the air flows through the system. Structural and functional impairments that affect the hard or soft palate typically create hypernasality. The voice is said to be hypernasal because too much air escapes through the nose when speaking. There is excessive nasality. In some instances, the escaping air creates an audible sound known as nasal escape or nasal emission. A cleft palate or neurological weakness affecting the movements of the soft palate are two conditions that may result in hypernasal resonance. Any condition which obstructs the airways above the larynx typically results in hyponasality. In contrast to hypernasality, the voice is hyponasal (i.e. lacking nasality) because insufficient air escapes through the noise when speaking. Most of us will have experienced hyponasality at some time when we have had a heavy cold or flu which has resulted in a blocked nose. Other conditions such as growths in the nasal cavity (e.g. nasal polyps) may result in hyponasal resonance. Hyper-Nasality: Too much sound coming from the nose during speech. Hypo-Nasality: Hyponasal speech, denasalization or rhinolalia clausa is a lack of appropriate nasal airflow during speech, such as when a person has nasal congestion. Some causes of hyponasal speech are adenoid hypertrophy, allergic rhinitis, deviated septum, sinusitis, myasthenia gravis. Cul-de-Sac Resonance: Airflow through the mouth is obstructed, often by enlarged tonsils, resulting in a “muffled” speech quality. Quality Disorders: Any conditions which disrupt the regular vibration of the vocal folds will likely lead to changes in quality. The noise that we perceive in someone’s voice because of disorganized vocal fold vibrations is known as hoarseness. Inadequate closure of the glottis (the space between the vocal folds) results in a breathy voice. Muscle weakness because of multiple sclerosis or Parkinsonism may result in breathiness. If the vocal folds are squeezed together with excessive force "hyperadduction" then the voice acquires a typically creaky or harsh quality. As well as neurological conditions such as cerebral palsy, general muscle tension and anxiety states can lead to harsh voice. In contrast to hyperadduction, if the vocal folds do not come together (adduct) at all then the voice is whispered. Paralysis of the recurrent laryngeal nerves of the larynx can lead to this condition. If the failure to fully adduct the vocal folds is intermittent, then the whispery voice comes and goes as some stretches of talk are voiced and others are voiceless. Hoarseness/Roughness: A voice that lacks clarity and is noisy. Hoarseness is most often caused by beign conditions, such as a cold, sore throat or vocal over use and usually goes away on its own. Hoarseness that persists for several weeks may represent a more serious problem that requires medical and therapeutic attention. Harshness: is due to the very strong tension of the vocal folds (especially medial compression and adductive tension), which results in an excessive approximation of the vocal folds. When the whole larynx is subjected to this extremely high tension, the upper larynx becomes highly constricted with the ventricular folds pressing on the upper surfaces of the vocal folds, making their vibration ineffective. Breathy Voice: The perception of audible air escaping thru the glottis during phonation. Muscular tension is low, with minimal adductive tension, weak medial compression and medium longitudinal tension of the vocal folds. Vocal fold vibration is inefficient, and, because of the incomplete closure of the glottis, a constant glottal leakage occurs which causes the production of audible friction noise. Air flows through the vocal folds at a high rate. Strain and Struggle: related to problems with initiating and maintaining voice. Flexibility: Flexibility refers to the ability to effortlessly vary paralinguistic features (particularly of pitch and loudness) to create an interesting and colorful voice capable of expressing a range of intellectual and emotional meanings. Consequently, conditions which limit variations in the pressure of the airflow through the larynx, the tension of the vocal folds, the strength of adduction and/or the lengthening and shortening of the vocal folds through rotational and sliding movements of the arytenoid cartilages can lead to reduced flexibility. Nonphonatory Vocal Disorders Stridor: noisy breathing or involuntary sounds that accompany inspiration and expiration Consistent Aphonia: a persistent absence of voice perceived as whispering Aphonia: uncontrolled and unpredictable aphonic breaks in voice Aphonia: Aphonia refers to an inability to produce voice naturally (i.e., due to physical impairment) and/or inability to produce voice by using a speech prosthesis (e.g., Passy-Muir valve, electrolarynx, tracheoesophageal puncture) due to physical disability or absence of larynx. Dysphonia: is a descriptive medical term meaning disorder (dys-) of voice (-phonia). There are many causes of dysphonia. Fortunately, more than half of people with voice complaints have a benign (noncancerous) cause. Functional Aphonia: It is common amongst women aged between puberty and age 40 and causes a high degree of breathy hoarseness, whispery voice, and aphonia during intentional vocalization, such as in conversations. Glottal closure is insufficient, and because aspirated air flows out of the glottal gap, the vocal cords do not vibrate. Although no voiced sound is produced during vocalization, a voiced sound is often produced when the patients cries, laughs, or coughs. Hypotonic Voice Disorders: These conditions produce a very weak, faint voice. If the airflow rate decreases due to vocalization muscle fatigue caused by psychosomatic factors, voice misuse, and/or respiratory organ disease, subglottal pressure does not rise, causing asthenic hoarseness. These conditions occur in neurological/muscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis and muscular dystrophy. Conversion Voice Disorders: Any loss of voluntary control over normal voice muscle or a consequence of environmental stress or interpersonal conflict. This disorder exists when there is psychological trauma. In the case of conversion dysphonia or aphonia (complete loss of voice), there may be a single traumatic event such as an accident, death, or psychologically damaging event, and there is change of voice within a short time. Or, there may be a long term psychologically damaging circumstance, such as sexual abuse, that may be manifested soon or many years later. In the case of conversion disorder, the individual may undergo functional voice therapy to gain control over his or her voice, but in most cases the voice disorder will not resolve unless there is also psychotherapy to address the underlying problem. Conversion Dysphonia: Characterized by an unreliable voice, Unpredictable pitch, amplitude, etc. for examples breathy vs normal quality, high vs low pitch, loud vs soft voice. Conversion Aphonia: Involuntary whispering despite a normal larynx, Gradual or sudden onset, can be triggered by an organic disorder, Psychotherapy often recommended. Approximately 80% of patients with conversion aphonia are female Conversion Mutism/Muteness: Most severe of conversion voice disorders. Patient makes no attempt to phonate or articulate or may articulate without exhalation. Common causes are patient history • Wanting, but not allowing oneself, to express an emotion verbally (such as fear, anger, or remorse) • A breakdown in communication with someone of importance to the patient • Shame or fear getting in the way of expressing feelings through normal speech and language Mutational Falsetto/Puberphonia: Failure to change from higher-pitched voice of preadolescence to lower-pitched voice of adolescence and adulthood. Male child or adolescent exhibits inappropriately high voice. This disorder exists when there is some psychological reason for an individual to resist the maturing and lowering pitch of the adult voice and maintains the higher pitch of a preadolescent. This disorder is much more common in adolescent males but can also exist in females. Juvenile Voice: Female companion to mutational falsetto, women maintains a child-like voice into adulthood. Spasmodic Dysphonia: Spasmodic dysphonia (SD), a focal form of dystonia, is a neurological voice disorder that involves involuntary "spasms" of the vocal cords causing interruptions of speech and affecting the voice quality. Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia: This is the most common type, and this affects the muscle that lies within the vocal folds, the thyroarytenoid muscle, it contracts strongly, but then spasms. The vocal folds squeeze together very tightly, causing a strained, strangled and harsh voice with voice arrests (stopping of the voice). Spasmodic Dysphonia causes an intermittent excessive closing of the vocal folds during vowel sounds in speech. Abductor Spasmodic Dysphonia: This causes the muscle that brings the vocal folds together or the cricoarytenoid muscle to contract suddenly. This produces a breathy voice and a lot of excess air coming out of the vocal folds. This is the less common form of Spasmodic Dysphonia. While in abductor Spasmodic Dysphonia, there is a prolonged vocal-fold opening during voiceless consonants. Mixed Spasmodic Dysphonia: This is when both types of spasms appear during speech, adductor and abductor in which an individual may demonstrate both types of spasms as he/she speaks. This is the rarest form of these three types. Disorder of Speech of Neurogenic Origin Dyspraxia: Dyspraxia refers to trouble with movement. That includes difficulty in four key skills: • Fine motor skills • Gross motor skills • Motor planning • Coordination Dyspraxia is a brain-based motor disorder. It affects fine and gross motor skills, motor planning, and coordination. It’s not related to intelligence, but it can sometimes affect cognitive skills. Dyspraxia is sometimes used interchangeably with developmental coordination disorder. Children born with dyspraxia may be late to reach developmental milestones. They also have trouble with balance and coordination. Into adolescence and adulthood, symptoms of dyspraxia can lead to learning difficulties and low self-esteem. Dyspraxia is a lifelong condition. There’s currently no cure, but there are therapies that can help you effectively manage the disorder. Dyspraxia Symptoms in Children: If your baby has dyspraxia, you might notice delayed milestones such as lifting the head, rolling over, and sitting up, though children with this condition may eventually reach early milestones on time. Other signs and symptoms can include: • Unusual body positions • General irritability • Sensitivity to loud noises • Feeding and sleeping problems • A high level of movement of the arms and legs As child grows, you might also observe delays in: • Crawling • Walking • Potty training • Self-feeding • Self-dressing Dyspraxia makes it hard to organize physical movements. For example, a child might want to walk across the living room carrying their schoolbooks, but they can’t manage to do it without tripping, bumping into something, or dropping the books. Other signs and symptoms may include: • Unusual posture • Difficulty with fine motor skills that affect writing, artwork, and playing with blocks and puzzles • Coordination problems that make it difficult to hop, skip, jump, or catch a ball • Hand flapping, fidgeting, or being easily excitable • Messy eating and drinking • Temper tantrums • Becoming less physically fit because they shy away from physical activities • Although intelligence isn’t affected, dyspraxia can make it harder to learn and socialize due to: • A short attention span for tasks that are difficult • Trouble following or remembering instructions • A lack of organizational skills • Difficulty learning new skills • Low self-esteem • Immature behavior • Trouble making friends Dyspraxia Symptoms in Adults: Dyspraxia is different for everyone. There are a variety of potential symptoms and they can change over time. These may include: • Abnormal posture • Balance and movement issues, or gait abnormalities • Poor hand-eye coordination • Fatigue • Trouble learning new skills • Organization and planning problems • Difficulty writing or using a keyboard • Having a hard time with grooming and household chores • Social awkwardness or lack of confidence Dyspraxia has nothing to do with intelligence. If you have dyspraxia, you may be stronger in areas such as creativity, motivation, and determination. Each person’s symptoms are different. Dyspraxia Causes: The exact cause of dyspraxia isn’t known. It could have to do with variations in the way neurons in the brain develop. This affects the way the brain sends messages to the rest of the body. That could be why it’s hard to plan a series of movements and then carry them out successfully. Dyspraxia Risk Factors: Dyspraxia is more common in males than females. It also tends to run in families. Risk factors for developmental coordination disorders may include: • Premature birth • Low birth weight • Maternal drug or alcohol use during pregnancy • A family history of developmental coordination disorders It’s not unusual for a child with dyspraxia to have other conditions with overlapping symptoms. Some of these are: • Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which causes hyperactive behaviors, difficulty focusing, and trouble sitting still for long periods • Autism spectrum disorder, a neurodevelopmental disorder that interferes with social interaction and communication • Childhood apraxia of speech, which makes it difficult to speak clearly • Dyscalculia, a disorder that makes it hard to understand numbers and grasp concepts of value and quantity • Dyslexia, which affects reading and reading comprehension Dysarthria: Speech is a unique, complex, dynamic motor activity through which human express thoughts and emotions and respond to and control the environment. Speech is among the most powerful tools possessed by human beings and it contributes enormously to the character and quality of lives. Speech requires the integrity and integration of numerous neurocognitive, neuromotor, neuromuscular, and musculoskeletal activities. The combined processes of speech motor planning, programming, control and execution are referred to as motor speech processes. Dysarthria can develop at any age, many of those who suffer from dysarthria are young children. Because of this motor speech disorder, children with dysarthria have difficulty controlling the muscles that control speech, such as the lips, jaws, tongue, larynx, and respiratory muscles. This prevents them from speaking clearly and can result in an inability to raise the volume of speech, involuntary mumbling, slurred speech, speech that is unusually fast or slow, or speech that lacks normal rhythm and intonation. Dysarthria is a collective name for a group of neurologic speech disorders that reflect abnormalities in the strength, speed, range, steadiness, tone, or accuracy of movements required for the breathing, phonatory, resonatory, articulatory, or prosodic aspects of speech production. This definition explicitly recognizes the following: • Dysarthria is neurologic in origin. • It is a disorder of movement. • It can be categorized into different types, each type characterized by distinguishable perceptual characteristics and different causes. Classification of Dysarthria: The order of the distinctive sorts of dysarthria involves Ataxic Dysarthria, Flaccid Dysarthria, Hyperkinetic Dysarthria, Hypokinetic Dysarthria, Mixed Dysarthria, Spastic Dysarthria and Unilateral Upper Motor Neuron Dysarthria. Each one of these dysarthria’s has its own pathogenesis. Ataxic Dysarthria: Ataxic dysarthria a type of motor speech disorder; its neuropathology is associated with cerebellar or cerebellar pathway lesions. The 10 abnormal language characteristics of ataxic dysarthria can be separated into three bunches: articulatory mistake, portrayed by imprecision of consonant creation, irregular articulatory breakdowns, and distorted vowels; prosodic abundance, described by excess and equivalent stress, prolongation of phonemes, delayed interims, and slow rate; and phonatory-prosodic deficiency, described by harshness, mono pitch, and mono loudness. Flaccid Dysarthria: Flaccid dysarthria is a perceptually distinct gathering of MSDs created by damage or sickness of one or more cranial or spinal nerves that supply speech muscles (lower motor neuron involvement) or lower motor neuron (LMN) pathways. They might be show in any or the greater part of the respiratory, phonatory, resonatory, and articulatory segments of language. The speech qualities can be followed to muscle weakness and diminished muscle tone, and their consequences for the speed, range and exactness of speech movements. Flaccidity (hypotonia) and weak muscle contractions and hypotonia are predominant neurological indications. Hyperkinetic Dysarthria: Hyperkinetic dysarthria a type of motor speech disorder; its neuropathology is damage to basal ganglia (extrapyramidal system), resulting in rapid involuntary movements and variable muscle tone; may affect all aspects of speech, but a dominant symptom is rate and prosodic disturbances; specific problems include prolonged intervals, variable rate, mono pitch, loudness variations, inappropriate silences, imprecise consonants, and distorted vowels; most effective treatment is medical; various medications help control involuntary movements. Hypokinetic Dysarthria: Hypokinetic dysarthria a type of motor speech disorder; its neuropathology is damage to basal ganglia (extrapyramidal system) resulting in slow movement, limited range of movement, and rigidity. Parkinsonism is the most frequent cause of this type of dysarthria; may affect all aspects of speech, but especially voice, articulation, and prosody; specific problems include mono pitch, mono loudness, reduced stress, imprecise consonants, variable rate of speech, increased speech rate in some cases and a slower rate in a few, short rushes of speech, inappropriate silences, and harsh and breathy voice. Is like the diminishments in the sufficiency of intentional movement (akinesia), slowness of movement (bradykinesia), muscular rigidity, tremor at rest. Mixed Dysarthria: Mixed dysarthria a type of motor speech disorder that is a combination of two or more pure dysarthria. It is associated with lesions of multiple systems. The neuropathology is varied depending on the types of dysarthria that are mixed; frequent causes include multiple strokes or multiple neurological diseases; speech disorders are varied and dependent on the types of pure dysarthria that are mixed. Spastic Dysarthria: Spastic dysarthria a kind of motor speech issue brought about by respective harm to the upper motor neuron (direct and indirect motor pathways). The symptoms of muscular dysfunction due to interruption of the upper motor neuron supply to the speech musculature that reflect in the speech output includes spasticity; weakness; restricted range of movement; and slowness of movement. Spastic dysarthria is show by slow, dragging, labored speech which is delivered with some difficulty. The most visible language deviations related to spastic dysarthria include: loose consonants, mono pitch, reduced stress, harsh voice quality, mono loudness, low pitch, slow rate, hyper nasality, strained, choked voice quality, short expressions, pitch breaks, constant hoarse voice and abundance and equivalent stress. Unilateral Upper Motor Neuron Dysarthria: Unilateral upper motor neuron dysarthria a type of motor speech disorder caused by damage to the upper motor neurons that supply cranial and spinal nerves involved in speech production; primarily a disorder of articulation in which the dominant speech problem is imprecise production of consonants; less significant speech symptoms include harsh voice quality, slow, imprecise, or irregular Alternating Motion Rates; generally slow rate of speech with increased rate in segments; mild hyper nasality; excess and equal stress. Causes of Dysarthria (Congenital, Acquired): Many neurologic illnesses, diseases, and disorders both acquired and congenital can cause dysarthria. Congenital or Developmental: The neurologic insult takes place at birth or prior to the development of speech and language. If a child has dysarthria at a very early age it may be due to birth injury, but it could also be caused by a congenital disorder. Some baby’s brains develop improperly or incompletely while still in the womb, and this can be caused by many different factors such as the mother’s diet, use of narcotics, medications, and other substances that negatively affect the child’s development. A child who has congenital dysarthria will already have the disorder even before they are born, but it may not be diagnosable until the child reaches an age when he or she should begin speaking. Acquired: Acquired: The individual may have developed some speech and language skills prior to the neurologic insult. Traumatic Brain Injury: One of the many childhood dysarthria causes is a traumatic brain injury. If a child suffers blunt force trauma to their head, this can cause serious brain damage that affects their ability to speak. This can occur at any age, but young children are very vulnerable because they have less ability to protect themselves. Some traumatic brain injuries occur during birth. When a child is being born, a large amount of pressure is put on the head by the vaginal walls or cervix. If there are any complications with the delivery, if it takes an excessive amount of time, the head compression may be severe enough to affect the brain. In addition, these same types of delivery complications can result in the child’s brain not receiving enough oxygen, also known as hypoxia. Just a few minutes of oxygen deprivation can result in lasting brain damage such as childhood dysarthria. Neurological Conditions: There are numerous neurological conditions that have been identified as childhood dysarthria causes. One of the leading causes of dysarthria is cerebral palsy. Though not every child with cerebral palsy will suffer from childhood dysarthria, there is a strong link. Some other neurological conditions that may cause dysarthria include: • Lou Gehrig’s disease • Muscular dystrophy • Guillain-Barre syndrome • Multiple sclerosis • Lyme disease • Huntington disease • Parkinson’s disease • Wilson’s disease • Myasthenia gravis In addition to these neurological disorders, strokes and brain tumors are also proven childhood dysarthria causes. Though strokes are more common in adults and especially those of advanced age, neonatal strokes have a strong potential to affect the speech centers of the brain and can affect these areas at a child’s most critical periods of cognitive development. When brain tumors are in the areas of the brain that control speech and respiratory function, they also have the potential to cause childhood dysarthria and severe respiratory problems. Disorders of Language Disorders of Language: A language disorder can cause issues with the comprehension and/or use of spoken, written, and other forms of language. Students with a language disorder may struggle with the form, content, or function of language. Language disorder is a communication disorder in which a person has persistent difficulties in learning and using various forms of language (i.e., spoken, written, sign language). Individuals with language disorder have language abilities that are significantly below those expected for their age, which limits the ability to communicate or effectively participate in many social, academic, or professional environments. Symptoms of language disorder first appear in the early developmental period when children begin to learn and use language. Language learning and use relies on both expressive and receptive skills. Expressive ability refers to the production of verbal or gestural signals, while receptive ability refers to the process of receiving and understanding language. Individuals with language disorder may have impairments in either their receptive or expressive abilities, or both. Overall, people with this condition have deficits in understanding and producing vocabulary, sentence structure, and discourse. Because people with language disorder typically have a limited understanding of vocabulary and grammar, they also have a limited capacity for engaging in conversation. Symptoms: Children with language disorder will typically be delayed in learning or speaking their first words and phrases. When they do speak, their sentences are shorter and less complex than would be expected for their age. Individuals with language disorder typically speak with grammatical errors, have a small vocabulary, and may have trouble finding the right word at times. When engaging in conversation, they may not be able to provide adequate information about the key events they’re discussing or tell a coherent story. Because children with language disorder may have difficulty understanding what other people say, they may have an unusually hard time following direction. It is common for deficits in comprehension to be underestimated, because people with language disorder may be good at finding strategies to cope with their language difficulties, such as using context to infer meaning. They may also appear to be shy or reserved, and they may prefer to communicate only with family members or other familiar people. Language skills are highly variable in young children, and many children who are late in speaking their first words or phrases do not develop language disorder. Delayed language acquisition is not predictive of language disorder until age 4, when individual differences in language ability become more stable. Language disorder that is diagnosed at age 4 or later is likely to be stable over time and often persists into adulthood. Although language disorder is present from early childhood, it is possible that the symptoms won’t become obvious until later in life, when the demands for more complex language use increase. There are three different types of language disorders, each with its own set of symptoms. An individual may have more than one type of language disorder. Forms of Language: Student struggles with • Phonology, or speech sounds and patterns • Morphology, or how words are formed • Syntax, or the formation of phrases and clauses Content of Language • Student struggles with: • Semantics, or the meaning of words Function of Language • Student struggles with: • Pragmatics, or how language is used in different contexts Causes: Communication disorders have a strong genetic component, and individuals with language disorder are more likely to have family members with a history of language impairment. Language disorder is also strongly associated with other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as specific learning disorder (literacy and numeracy), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and developmental coordination disorder. Language Delay: A language delay is language development that is significantly below the norm for a child of a specified age. Language delay is a communication disorder, a category that includes a wide variety of speech, language, and hearing impairments. The milestones of language development, including the onset of babbling and a child's first words and sentences, normally occur within approximate age ranges. However, individual children vary enormously regarding the exact age at which each milestone is reached. There also are different styles of language development. Most children have acquired good verbal communication by the age of three. But one child may be wordless until the age of two and a half and then immediately start talking in three-word sentences. Another child might have several words at ten months but add very few additional words over the following year. Other children start talking at about 12 months and progress steadily. Language delay usually becomes apparent during infancy or early childhood. Any delay in general development usually causes language delay. Children with language delay may acquire language skills in the usual progression but at a much slower rate, so that their language development may be equivalent to a normally developing child of a much younger chronological age. Maturation delay, also called developmental language delay, is one of the most common types of language delay. Children with a maturation delay may be referred to as "late talkers" or "late bloomers." Maturation delays frequently run in families. Causes and symptoms Environmental causes: Common nonphysical causes of language delay include circumstances in which the following are the case: • The child is concentrating on some other skill, such as walking perfectly, rather than on language. • The child has a twin or sibling very close in age and thus may not receive as much individual attention. • The child has older siblings who interpret so well that the child has no need to speak or whose talk is so continuous that the child lacks the opportunity to speak. • The child is in a daycare situation with too few adults to provide individual attention. • The child is under the care of a non-English speaker. • The child is bilingual or multilingual, learning two or more languages simultaneously but at a slower speed; the child's combined comprehension of the languages is normal for that age. • The child suffers from psychosocial deprivation such as poverty, malnutrition, poor housing, neglect, inadequate linguistic stimulation, emotional stress. • The child is abused; abusive parents are more likely to neglect their children and less likely to communicate with them verbally. Physical causes: Language delay may result from a variety of underlying disorders, including the following: • mental retardation • maturation delay (This delay in the maturation of the central neurological processes required to produce speech is often the cause of late talking.) • hearing impairment • dyslexia, a specific reading disorder which may cause language delay in preschoolers • a learning disability • cerebral palsy, in which numerous factors may contribute to language delay • autism, a developmental disorder in which, among other things, children do not use language or use it abnormally • congenital blindness, even in the absence of other neurological impairment • brain damage • Klinefelter syndrome, a disorder in which males are born with an extra X chromosome • receptive aphasia or receptive language disorder, a deficit in spoken language comprehension or in the ability to respond to spoken language, resulting from brain damage • expressive aphasia, an inability to speak or write, although comprehension is normal; caused by malnutrition, brain damage, or hereditary factors • childhood apraxia of speech, a nervous system disorder Mental retardation accounts for more than 50 percent of language delays. Language delay is usually more severe than other developmental delays in retarded children, and it is often the first noticeable symptom of mental retardation. Mental retardation causes global language delay, including delayed auditory comprehension and use of gestures. Impaired hearing is one of the most common causes of language delay. Any child who does not hear speech in a clear and consistent manner will have language delay. Even a minor hearing impairment can significantly affect language development. In general, the more severe the impairment, the more serious the language delay. Children with congenital (present at birth) hearing impairment or hearing loss that occurs within the first two years of life (known as prelingual hearing loss) experience serious language delay, even when the impairment is diagnosed and treated at an early age. However, deaf children born to parents who use sign language develop infant babble and a fully expressive sign language at the same rate as hearing children. Symptoms of language delay: Symptoms of language delay include the following • failure to meet the developmental milestones for language development • language development that lags behind other children of the same age by at least one year • inability to follow directions • slow or incomprehensible speech after three years of age • serious difficulties with syntax (placing words in a sentence in the correct order) • serious difficulties with articulation, including the substitution, omission, or distortion of certain sounds Language delays resulting from underlying conditions may have symptoms specific to the condition. Nonetheless, specific symptoms of language delay may include the following: • not babbling by 12 to 15 months of age • not understanding simple commands by 18 months of age • not talking by two years of age • not using sentences by three years of age • not being able to tell a simple story by four or five years of age Symptoms of language delay with mental retardation: Mentally impaired children usually babble during their first year and may speak their first words within the normal age range. However, they often cannot do the following: • put words together • speak in complete sentences • acquire a larger, more varied vocabulary • develop grammatically Mentally impaired children in conversation may be repetitive and routine, exhibiting little creativity . Nevertheless, vocabulary and grammatical development appear to proceed by very similar processes in mentally retarded and developmentally normal children. In general, the severity of language delay depends on the severity of the mental retardation. Levels of retardation and language skill are ranked as follows: • mild retardation (intelligence quotient [IQ] range of 52–68): usually eventually develop language skills • moderate retardation (IQ range of 36–51): usually learn to talk and communicate • severe retardation (IQ range of 20–35): have limited language but can speak a few words Language delays among mentally retarded children vary greatly. Some severely mentally impaired children who also have hydrocephalus or Williams syndrome may acquire exceptional conversational language skills, sometimes called the "chatterbox syndrome." Some children (called savants) test as mentally retarded but learn their native language, as well as foreign languages, very easily. With Down syndrome and some other disorders, language delay is more severe than other mental impairments. This factor may be due to the characteristic facial abnormalities and relatively large tongues of Down-syndrome children. Children with Down syndrome also are at higher risk for hearing impairment and ear infections that cause hearing loss. Symptoms of language delay with other disorders: Symptoms of language delay in a hearingimpaired child include the following: • babbling at an older-than-normal age • babbling that is less varied and less sustained • first words at age two or older • only two-word sentences by age four or five in a profoundly deaf child Dyslexic children have difficulty separating parts of words and single words within a group of words. Symptoms of dyslexia may include: • poor articulation • difficulties identifying sounds within words, blending sounds, or rhyming • difficulty putting sounds in the correct order • hesitation in choosing words A learning-disabled child usually exhibits an uneven pattern of language development. In addition, about 50 percent of autistic children never learn to speak. Those who do speak often have severe language delay and may use words in unusual ways. They rarely participate in interactive dialogue and often speak with an unusual rhythm or pitch. The speech of some autistic children has an atonic or sing-song quality. Children with congenital blindness average about an eight-month delay in speaking words. Although blind children develop language in much the same way as sighted children, they may rely more on conversational formulas. The speech of children with receptive aphasia is both delayed and sparse, ungrammatical, and poorly articulated. Children with expressive aphasia fail to speak at the usual age although they have normal speech comprehension and articulation. Children with defined lesions in language areas on either side of the brain have initial but quite variable language delays. Usually their language catches up by the age of two or three without noticeable deficits. Apraxia affects the ability to sequence and vocalize sounds, syllables, and words. Children with apraxia know what they want to say, but their brains do not send the correct signals to the lips, jaw, and tongue to form the words. In addition to language delay, apraxia often causes other expressive language disorders. Specific Language Impairment: Specific language impairment (SLI) is a developmental language disorder characterized by the inability to master spoken and written language expression and comprehension, despite normal nonverbal intelligence, hearing acuity, and speech motor skills, and no overt physical disability, recognized syndrome, or other medical factors known to cause language disorders in children. A variety of components of oral language may be affected by SLI, including grammatical and syntactic development (e.g., correct verb tense, word order and sentence structure), semantic development (e.g., vocabulary knowledge) and phonological development (e.g., phonological awareness, or awareness of sounds in spoken language). Children may manifest receptive difficulties, that is, problems understanding language, or expressive difficulties, involving use of language. Oral language difficulties are associated with a wide range of disabilities, including hearing impairment, broad cognitive delays or disabilities, and autism spectrum disorders. Specific language impairment differs from the preceding conditions. Although it is always important to rule out hearing problems as a source of language difficulties including fluctuating hearing loss such as that associated with repeated ear infections most children with SLI have normal hearing. Furthermore, specific language impairment does not involve global developmental delays; children with SLI function within the typical range in non-linguistic areas, such as nonverbal social interaction, play, and self-help skills (e.g., feeding and dressing themselves). Children with autism spectrum disorders have core impairments in social interaction and communication, including both nonverbal and verbal skills, as well as certain characteristic behaviors (e.g., repetitive movements, lack of pretend play, and inflexible adherence to routines) that are not found in youngsters with SLI. Specific language impairment puts children at clear risk for later academic difficulties, in particular, for reading disabilities. Children with SLI will have problems in learning to read, presumably because reading depends upon a wide variety of underlying language skills, including grammar and syntax, semantics, and phonological skills. Disorders of Language of Neurogenic Origin Aphasia: Aphasia is an acquired disorder of spoken and written language (Greek: dys-, disordered; phasis, utterance). Aphasia is a type of disorder where a person has difficulties comprehending language or speaking due to some type of damage in the parts of the brain responsible for communication. The symptoms of Aphasia vary based on the region of the brain that was damaged. There are different regions responsible for understanding language, speaking, reading, and writing, though typically they are found in the left side of the brain. Sometimes dysphasia is also referred to as aphasia, though generally it's considered a less severe version of aphasia. Aphasia is an acquired neurogenic language disorder resulting from an injury to the brain, most typically, the left hemisphere. It involves varying degrees of impairment in four primary areas: • Spoken language expression • Spoken language comprehension • Written expression • Reading comprehension Signs and Symptoms : Common signs and symptoms of aphasia include the following: Impairments in Spoken Language Expression • Having difficulty finding words (anomia) • Speaking haltingly or with effort • Speaking in single words (e.g., names of objects) • Speaking in short, fragmented phrases • Omitting smaller words like the, of, and was (i.e., telegraphic speech) • Making grammatical errors • Putting words in the wrong order • Substituting sounds or words (e.g., “table” for bed; “wishdasher” for dishwasher) • Making up words (e.g., jargon) • Fluently stringing together nonsense words and real words, but leaving out or including an insufficient amount of relevant content Impairments in Spoken Language Comprehension • Having difficulty understanding spoken utterances • Requiring extra time to understand spoken messages • Providing unreliable answers to “yes/no” questions • Failing to understand complex grammar (e.g., “The dog was chased by the cat.”) • Finding it very hard to follow fast speech (e.g., radio or television news) • Misinterpreting subtleties of language (e.g., taking the literal meaning of figurative speech such as “It's raining cats and dogs.”) • Lacking awareness of errors Impairments in Written Expression (Agraphia) • Having difficulty writing or copying letters, words, and sentences • Writing single words only • Substituting incorrect letters or words • Spelling or writing nonsense syllables or words • Writing run-on sentences that don’t make sense • Writing sentences with incorrect grammar Impairments in Reading Comprehension (Alexia) • Having difficulty comprehending written material • Having difficulty recognizing some words by sight • Having the inability to sound out words • Substituting associated words for a word (e.g., “chair” for couch) • Having difficulty reading non-content words (e.g., function words such as to, from, the) Aphasia is often classified into • Nonfluent • Fluent • Subcortical Fluent Aphasia (Receptive Aphasia) Fluent aphasia is caused by lesions in the posterior brain structures. Word substitutions, neologisms, and verbose verbal output. In this form of aphasia, the ability to grasp the meaning of spoken words and sentences is impaired, while the ease of producing connected speech is not very affected. • Wernicke’s Aphasia: lesions in Wernicke’s area the posterior portion of the superior temporal gyrus in the left hemisphere of the brain. Wernicke’s area is supplied by the posterior branch of the left middle cerebral artery. Stroke of lower division of left middle cerebral artery cause Wernicke’s Aphasia. Wernicke's area is the region of the brain that is important for language development. Brodmann area 22 in human brain, is the area involve in auditory comprehension. The Wernicke's area is responsible for the comprehension of speech. Wernicke’s aphasia is also referred to as ‘fluent aphasia’ or ‘receptive aphasia’. Individuals with Wernicke’s Aphasia have o Fluent but often meaningless speech o Jumbled content. o Ability to grasp the meaning of spoken words and sentences is impaired o Reading and writing are severely impaired o Can produce many words o Speak using grammatically correct sentences with normal rate and prosody o What they say doesn’t make a lot of sense or use irrelevant words, Paraphasic, Neologism o Not realize using the wrong words o Not fully aware what they say o Profound language comprehension deficits • Anomic Aphasia: A variety of locations, often in posterior language regions, but some in frontal lobe. lesion in the angular gyrus region. Anomic aphasia is one of the milder forms of aphasia. Individuals with Anomic Aphasia have o Word retrieval difficulties. o Their speech is fluent and grammatically correct o Significant word-finding difficulties o Circumlocutions (attempts to describe the word they are trying to find). o Understand speech well o Can repeat words and sentences o Can read adequately. Difficulty finding words is evident in writing as it is in speech. • Conduction Aphasia: A lesion in the arcuate fasciculus, deep supramarginal gyrus, or superior temporal gyrus Individuals with Conduction Aphasia have o Speak Fluently o Paraphasic output o Good auditory comprehension o Poor repetition This condition is caused by damage to the arcuate fasciculus, which you can think of as a bundle of nerves that connects two parts of your brain. These parts are Broca's area and Wernicke's area. Broca's area is the part of your brain responsible for speech production, and Wernicke's area is the part of your brain responsible for speech comprehension. • Transcortical Sensory Aphasia: Border zone regions of the territories of the middle cerebral and the posterior cerebral arteries, sparing Wernicke’s area. Lesions in the inferior left temporal lobe of the brain located near Wernicke's area. Individuals with Transcortical Sensory Aphasia have o Word errors, preservation o Strong ability to repeat words and phrases. The patient may repeat questions rather than answer them ("echolalia"). o Poor auditory comprehension o Fluent speech with semantic paraphasia’s present. Nonfluent Aphasia (Expressive Aphasia) Non-fluent means that the patient has trouble getting words out, but usually has good understanding. Generally caused leisions in the anterior brain structures. Slow, labored speech; word retrieval and syntactic problems. • Broca’s Aphasia: A large frontal lesion affecting Broca’s area and surrounding cortical regions as well as white matter deep to Broca’s area. Stroke of upper division of left middle cerebral artery. Broca's area is one of several language areas on the left hemisphere of the brain. Brodmann area 44 and 45 in human brain, is the area involve in production of language. Individuals with Broca’s aphasia have o Agrammatism o Effortful articulation o Short utterances o Impaired prosody and intonation o Good comprehension o Word finding difficulties o Poor repetition This type of aphasia is also known as non-fluent or expressive aphasia. • Transcortical Motor Aphasia: A frontal lobe lesion often anterior and/or superior to Broca’s area, sometimes in the territory of the anterior cerebral artery. Lesion in the border zone superior or anterior to Broca’s area. Individuals with Transcortical Motor Aphasia have o Little to no initiation of spontaneous speech o Excellent imitation (even of long utterances) o Relatively intact comprehension o Reading comprehension is good o Syntax not as bad as in Broca’s aphasia. o Capable of naming and repeating words normally • Mixed Transcortical Aphasia: is milder form impairment in all modalities blend of fluent and nonfluent characteristics. This type of aphasia can also be referred to as "Isolation Aphasia". This type of aphasia is a result of damage that isolates the language areas (Broca’s, Wernicke’s, and the arcuate fasciculus) from other brain regions. Broca’s, Wernicke’s, and the Arcuate Fasciculus are left intact; however, they are isolated from other brain regions. Individuals with Mixed Transcortical Aphasia have o Severe speaking and comprehension impairment o Preserved repetition. o Difficulty to understand what is being said to them, o Non-fluent o Cannot name objects o Cannot read or write • Global Aphasia: Global Aphasia is caused by injuries to multiple language-processing areas of the brain, including those known as Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas. These brain areas are particularly important for understanding spoken language, accessing vocabulary, using grammar, and producing words and sentences. A large lesion affecting the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes, or a smaller deep lesion affecting pathways from both anterior and posterior language regions. Global aphasia may often be seen immediately after the patient has suffered a stroke or a brain trauma. Symptoms may rapidly improve in the first few months after stroke if the damage has not been too extensive. Individuals with Global Aphasia have o Severe deficits in all areas of language comprehension and production o Output may be limited to stereotypic utterances o Can produce few recognizable words o Understand little or no spoken language o Neither read nor write o Preserved intellectual and cognitive capabilities unrelated to language and speech. Subcortical Aphasias: Subcortical aphasia is a condition characterized by partial or total loss of the ability to communicate verbally and it develops because of damage to subcortical brain areas without loss of cortical function in Broca's or Wernicke's areas. A form of aphasia that results from damage to subcortical regions such as the thalamus, internal capsule, and the basal ganglia. o Little spontaneous speech o Impaired executive language functions such as word fluency and sentence generation, but it largely spares responsive language functions such as comprehension, repetition, and naming o Thalamic aphasia may produce dysfunction at the prelinguistic level, such as impairments in concept generation and dysfunction in the control of preformed speech patterns o For aphasia related to white matter lesions, the primary language dysfunction is an impairment in speech motor output. Bilingual and Multilingual Aphasia: With increased rates of “globalization”, the proportion of individuals who speak more than one language is rapidly expanding. The term ‘‘Bilingual’’ or "Multilingual" refers to all those people who use two or more languages or dialects in their everyday lives. Bilingual people with aphasia who speak two or more languages may find each language is similarly affected or that one language is more affected than the others. The best-recovered language may be the first language (mother tongue) or can be the language most frequently used. For individuals who were less proficient in their second language, aphasia may lead to apparent loss of the second language. o Aphasia can cause alternating difficulties between languages or difficulty in translating between languages o Sometimes aphasia causes difficulty in selecting the appropriate language, and leads to use of the non-target language e.g. speaking Italian with English speakers or switching between Italian and English where normally only one language is spoken o Bilingual individuals with aphasia who usually switch languages with other bilinguals may find this harder to do or may do so incorrectly because of the aphasia. o Often these patterns change over time and may be most acute in the early stages after a stroke or trauma. o For other bilinguals with aphasia there are difficulties in each language but selecting the right language and switching between languages is unaffected. Because of the differences that often occur after aphasia, it is important to have speech-language assessment in each of the languages that are used, even if English is the language that has previously been spoken the most. Causes of Aphasia: Aphasia is caused by damage to the language centers of the brain. These language centers are in the left hemisphere, but aphasia can also occur as a result of damage to the right hemisphere. Common causes of aphasia include the following: • Stroke • Traumatic brain injury • Brain tumors • Brain surgery • Brain infections • Progressive neurological diseases (e.g., dementia) Stroke is the most common cause of aphasia. Stroke: Aphasia is usually caused by a stroke or brain injury with damage to one or more parts of the brain that deal with language. According to the National Aphasia Association, about 25% to 40% of people who survive a stroke get aphasia. A stroke occurs when the blood supply to your brain is interrupted or reduced. This deprives your brain of oxygen and nutrients, which can cause your brain cells to die. A stroke may be caused by a blocked artery (ischemic stroke) or the leaking or bursting of a blood vessel (hemorrhagic stroke). The signs of a stroke include a sudden severe headache, weakness, numbness, vision problems, confusion, trouble walking or talking, dizziness and slurred speech. Traumatic brain injury: TBI also known as craniocerebral trauma, is injury to the brain sustained by physical trauma or external force. Brain injuries can be penetrating or nonpenetrating. Common Causes of (TBI) are Falls, Automobile accidents, Crashing into objects, Assault of the head, Gunshot wounds and Alcohol and drug abuse. Primary damage to the brain is caused by impact to the head. Secondary damage to the brain is caused by Infection, Hypoxia, Edema or swelling, Elevated intracranial pressure, Infarction or tissue death and Hematoma or focal bleeding. Tumors: Tumors growing within the brain can be PRIMARY or SECONDARY (metastatic) onequarter of patients with primary brain tumors have language disturbances at the time of initial presentation. The tissue around tumor swells, if tumor is in language area Aphasia can occur. Hydrocephalus: Hydrocephalus refer to enlargement of the cerebral ventricles due to increase in cerebrospinal fluid. It Can result in aphasia Infections: Bacterial Meningitis: The pia matter, arachnoid and cerebrospinal fluid become infected, causing inflammation/ swelling resulting in Aphasia and other symptoms. Brain Abscess: It is caused by bacteria, fungus or parasites entry in brain tissues from some infection which is present in other body part outside brain. Transmission can be through blood or tissues. Toxemia: When nervous system encounter substance that poison nerve tissues, it can be due to Drug overdose, Heavy metal poisoning (lead, mercury) and Chemical poisoning. Dementia: Dementia is a general term for loss of memory and other mental abilities severe enough to interfere with daily life. It is caused by physical changes in the brain. Alzheimer's is the most common type of dementia. Dementia: Dementia is an overall term for diseases and conditions characterized by a decline in memory, language, problem-solving and other thinking skills that affect a person's ability to perform everyday activities. Memory loss is an example. Alzheimer's is the most common cause of dementia. Dementia is not a single disease; it’s an overall term that covers a wide range of specific medical conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease. Disorders grouped under the general term “dementia” are caused by abnormal brain changes. These changes trigger a decline in thinking skills, also known as cognitive abilities, severe enough to impair daily life and independent function. They also affect behavior, feelings and relationships. Symptoms of Dementia: Symptoms of dementia can vary greatly. Examples include: • Problems with short-term memory. • Keeping track of a purse or wallet. • Paying bills. • Planning and preparing meals. • Remembering appointments. • Traveling out of the neighborhood. Many dementias are progressive, meaning symptoms start out slowly and gradually get worse. Causes: Dementia is caused by damage to brain cells. This damage interferes with the ability of brain cells to communicate with each other. When brain cells cannot communicate normally, thinking, behavior and feelings can be affected. The brain has many distinct regions, each of which is responsible for different functions (for example, memory, judgment and movement). When cells in a particular region are damaged, that region cannot carry out its functions normally. Different types of dementia are associated with particular types of brain cell damage in particular regions of the brain. For example, in Alzheimer's disease, high levels of certain proteins inside and outside brain cells make it hard for brain cells to stay healthy and to communicate with each other. The brain region called the hippocampus is the center of learning and memory in the brain, and the brain cells in this region are often the first to be damaged. That's why memory loss is often one of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer's. Most changes in the brain that cause dementia are permanent and worsen over time, thinking and memory problems caused by the following conditions may improve when the condition is treated or addressed: • Depression. • Medication side effects. • Excess use of alcohol. • Thyroid problems. • Vitamin deficiencies. Types of Dementia: Dementia is a general term for loss of memory and other mental abilities severe enough to interfere with daily life. It is caused by physical changes in the brain. Alzheimer's is the most common type of dementia, but there are many kinds. • Lewy Body Dementia • Down Syndrome and Alzheimer's Disease • Frontotemporal Dementia • Huntington's Disease • Mixed Dementia • Posterior Cortical Atrophy • Parkinson's Disease Dementia • Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): TBI also known as craniocerebral trauma, is injury to the brain sustained by physical trauma or external force. Brain injuries can be penetrating or nonpenetrating. Common Causes of (TBI) are Falls, Automobile accidents, Crashing into objects, Assault of the head, Gunshot wounds and Alcohol and drug abuse. Primary damage to the brain is caused by impact to the head. Secondary damage to the brain is caused by Infection, Hypoxia, Edema or swelling, Elevated intracranial pressure, Infarction or tissue death and Hematoma or focal bleeding. Types of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) 1. Open Head Injury 2. Closed Head Injury Open Head Injury: Result when the scalp and skull are penetrated caused by Bullets, Shell Fragments, Knives and Blunt instruments. Primary damage is typically localized along the path of the object. Primary damage may also result from bone fragments. Secondary Damage is Increased intracranial pressure, Swelling, Bleeding and Infection. It rarely leads to coma. Risk of epilepsy is greater. Closed Head Injury: The result of mechanical forces including the effects of both direct contact and inertia. Damage results from the inward compression of the skull at the point of impact and the subsequent rebound effects. Closed head injury literally causes the brain to bounce around against the rough and sometime jagged inner surface of the skull. Coup/contra coup damage results in confusions and bruising. Closed head injury results in decreased capacity to regulate Behavior, Emotions, Attention, Memory, Mental processing speed, Attention and Executive functions. Effects of a Traumatic Brain Injury There is a. wide range of physical, cognitive, and behavioral effects which can result from brain injuries. The injuries often cause diffuse damage and many interrelated brain functions can be affected. Each brain injury differs from child to child as does the rate and degree of recovery. Children with TBI have great potential for growth and development. They often make remarkable progress in many areas and compensate for losses by developing new strengths. Below are possible effects following traumatic brain injury, will assist the educator in determining student needs and identifying appropriate services and strategies to facilitate the child's success in school. Initial Effects: In the first few days following trauma, the child may experience a variety of medical and physical complications, including swelling of the brain, edema (excess cerebral-spinal fluid), respiratory difficulty, and seizures. Motor problems are often experienced early. Examples include rigidity, spasticity, coordination difficulties, and tremors. As the child emerges from coma, he/she may experience temporary neurologically based irritability, agitation, and aggression or may lack any emotional expression. As the child improves, he/she may be able to follow simple 1·omines and directions. The child may show memory for past events but remain confused with poor memory of recent and current events. These early, immediate problems usually din1inish very rapidly and the oven symptoms subside considerably. This early, relatively rapid improvement is often interpreted as an indicali6n that subsequent recovery will be as rapid and complete. However, children 'with severe, moderate, and sometimes even mild injuries, may have persistent cognitive, behavioral. and sensory-motor difficulties. Cognitive Effects: Traumatic brain injuries in children can have delayed effects on cognitive functions. Some difficulties become apparent only as the child continues through developmental stages and has new and different educational demands. Effects of the brain injury occurring before the cognitive functions fully develop may nor become apparent until a later age. For example, abilities in planning and problem solving are usually quite undeveloped in early childhood. Cognitive difficulties in these areas may not become apparent until the student is older and would be expected to have these skills more developed. Long-term cognitive effects are typically experienced by children with TBI and can affect memory, attention, concentration, and executive functions. Memory: Memory deficits are among the more common and lasting effects following brain injury. Children may have difficulty with encoding, storing, and retrieving new information. This is particularly true when the information is presented quickly or in great amounts or in detail. These difficulties can affect the child’s ability to learn new curriculum material, new social and behavioral skills, and new spatial integrative tasks. Because prior memory can often be well preserved, teachers may not initially realize the difficulty a student is having in learning new academic material, in finding the way around a new school building, or in dealing with new social demands. Early intervention to address memory difficulties is important to a child's success after a traumatic brain injury. Attention and Concentration: Brain injuries also often affect the child's ability to attend and concentrate. The student is likely to experience problems focusing and sustaining attention for long periods of time. A student may not fully comprehend a direction because he/she is unable to filter out distractions in the classroom or may have difficulty functioning in situations where there is a great deal of stimulation. Since the student cannot selectively attend to important stimuli, he/she may "overload" quickly and can become quite agitated or confused. Attention problems may also affect the student's ability to shift from one topic or activity to another. After brain injury child may be able to process only small amount of information. When given too much, he/she may stop processing completely and therefore miss information. Executive Functions: Executive functions have major implication for the child's school performance. Impaired executive functions are most commonly associated with damage to the frontal lobes of the brain. This is an area commonly affected in closed head injury. Executive function deficits may include the following: ▪ Setting realistic goals: The student often lacks the self-awareness necessary to establish realistic goals. ▪ Planning and organizing behavior: The student is often unable to identify and organize the sequence of steps to reach a goal. ▪ Initialing a task: The student may have the skill carry out a task but has difficulty initiating the activity. ▪ Self-inhibiting: The student may be impulsive or unable to inhibit inappropriate statements, emotions. or behaviors creating social and behavioral difficulties. ▪ Monito1ing and evaluating performance: The student mau be unable to adequately monitor his/her behavior in learning or social situations. Often the student is unable to objectively predict the outcome of the behavior, evaluate what he/she has done. or understand the effect of this behavior on another person. ▪ Problem solving: The student may have difficulty in perceiving the nature of a problem and considering a variety of possible solutions. It is common for students with TBI to consider only one possible solution to problems and to fail to consider relevant information in weighing the merits of possible solutions. Students may revert to methods of problem solving such as trial and error which arc typical of younger children and less efficient than expected for their age and academic level. Executive system impairments also include difficulties in transferring newly acquired skills to alternate settings. Transference of skills should be a planned process. This reinforces the need to assess and teach skills to students with TBI in environments in which the skills will be used. Speech and Language Effects: Speech problems evident early after brain injury, such as lack of speech or extremely slow speech, often improve significantly in the early stages of recovery. If speech problems persist, they may include speaking in monotone, slow rate of speech or imprecision in articulation. Most d1ildren with brain injury recover motor speech functions. While vocabula1y often recovers to preinjury levels, over time problems with new learning may have a pronounced effect on vocabulary development. Students with TBI usually have ongoing higher-level language and communication problems which can have consequences for academic and social success. In expressive language, difficulties in confrontation naming (naming things or people upon visual presentation) and word retrieval (coming up with the names for things or people in spontaneous speech) are common, particularly under stress. There is usually a sharp deterioration in written and verbal communication as the amount of information to be expressed increases. Short responses or sentences may be adequately spoken or written whereas extended descriptions or narratives may be extremely disorganized. Comprehension of spoken language by children with TBI often deteriorates sharply with increases in ▪ the rate of speech ▪ the amount of information to be processed (beyond sentence length) ▪ the abstractness of the language spoken ▪ interference from the environment (such as a busy classroom or hallway or noisy, active lunchroom). Social communication may be greatly affected after a brain injury. The ability to participate appropriately in conversation requires the use of cognitive, linguistic, and social skills, many of which are affected following TBI. These include sustained attention to shifting topics, accurate perception and interpretation of social cues, retention and integration of information already presented, organization of ideas, retrieval of words to accurately express ideas, and application of rules of social appropriateness. As a result, disorganized socially inappropriate conversation is common in students with traumatic brain injury. Students may produce language that is inappropriate to the setting (because of impulsiveness or impaired social judgment), wander unpredictably in conversation, fail to initiate interaction, or have difficulty inhibiting or terminating interaction. These common difficulties in the pragmatic domain of language easily cause the child with a traumatic brain injury to seem "different"-socially awkward-and to lose friends. Behavioral Effects: Traumatic brain injury often has a pronounced effect on a student's behavior. Many times, the changes reflect an exacerbation of challenging behaviors the child had prior to the injury. There are other behaviors that may occur as a direct result of the injury and as such are new responses for the child. Behavior changes in children with TBI can result from: ▪ neurological damage to the brain ▪ cognitive-communicative problems ▪ feelings of failure and frustration that lead to acting-out or withdrawal ▪ situations that are overly demanding, confusing, or stimulating ▪ preinjury behavior problems. Difficulties that can result from physical injury or resulting chemical imbalance in the brain include agitation and irritability, mood swings. hyperactivity, and apathy. Emotional and behavioral outbursts may seem to be unprecipitated by events in the environment and may not be under the child's direct control. Disruptions in the brain following an injury can also cause changes in a child's activity level. Some children may display a high degree of agitation with impaired concentration and attention. Others have pronounced lethargy with great difficulty initiating activities. Sensory Effects: Brain injury can cause complex visual disabilities such as double vision and impaired coordination of both eyes. In some cases, the brain's visual processing areas are injured resulting in visual field cuts or partial losses of vision. However, because the brain attempts to fill in the missing areas, the individual may feel he/she is seeing completely. These students can have significant reading problems (words or parts of words can be cut off). Students may also experience difficulty reading the chalkboard or charts. Comprehensive assessments of visual functions are important to identify any special problems experienced the children with TBI and the need for classroom accommodations or visual aids. Young children in particular are not adept at identifying losses in their visual field, A screening for visual ability is an important part of early assessment and should he have considered for all students with TBI Consultation with a vision specialist is recommended if visual problems are suspected. Hearing loss ls also a common outcome of traumatic brain injury in children. An acceleration dependent injury to the head can cause hearing problems due to damage to the external ear, the middle ear, the inner ear, the auditory nerve, or the auditory center of the brain resulting in conductive sensorineural, and/or cortical hearing impairment. Motor and Physical Effects: Motor skills often recover to point where normal independent functioning occurs following a brain injury. In some cases, motor recove1y can plateau, leaving some long-term motor problems. Difficulties with balance, gait, strength, range of motion, and coordination may continue. Fatigue and lack of endurance are very frequent after TBI. Children often tire very quickly and may be unable to persist on a task. Sharp reductions in the child's cognitive processing abilities such as attention and concentration, at various times during the day are often indicative of neurologically based fatigue. Simply recommending that the child go to bed earlier at night may not improve this type of intermittent fatigue. Frequent changes to less demandi.ng activities and rest periods are usually necessary. Feeding and Swallowing Disorders Mastication: Mastication refers to the processes involved in food preparation, including moving the unchewed food onto the grinding surface of the teeth, chewing it, and mixing it with saliva in preparation for swallowing. Deglutition: Deglutition refers to swallowing. These two biological processes require the integration of lingual, velar, pharyngeal, and facial muscle movement with laryngeal adjustments and respiratory control. During the mastication and deglutition process, all muscles inserting into the orbicularis oris may be called into action to open, close, purse, and retract the lips as food is received. All intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue will be invoked to move the food into position for chewing and preparation of the bolus (either liquid or a mass of food) for swallowing. The velar elevators seal off the nasal cavity to prevent regurgitation, and the pharyngeal constrictors must contract in a highly predictable fashion to move the bolus down the pharynx and into the esophagus. With the addition of laryngeal elevation, more than 55 pairs of muscles whose timing and innervation patterns must be coordinated through the accurate activation of cranial and spinal nerves. Swallowing: Swallowing, sometimes called deglutition is the process in the human or animal body that allows for a substance to pass from the mouth, to the pharynx, and into the esophagus, while shutting the epiglottis. Swallowing is an important part of eating and drinking. If the process fails and the material (such as food, drink, or medicine) goes through the trachea, then choking or pulmonary aspiration can occur. In the human body the automatic temporary closing of the epiglottis is controlled by the swallowing reflex. The portion of food, drink, or other material that will move through the neck in one swallow is called a bolus. Dysphagia or Swallowing Disorders: Swallowing disorders, also called dysphagia is the medical term for the symptom of difficulty in swallowing. It can occur at different stages in the swallowing process, Oral phase, sucking, chewing, and moving food or liquid into the throat. Swallowing disorders include many diseases and conditions that cause difficulty in passing food or liquid from the mouth into the throat and esophagus, moving food down the esophagus, or having a sensation of pain during swallowing. Causes and Symptoms of Swallowing Problems: The causes and symptoms of swallowing problems depend on the location of the difficulty. They are usually grouped into two categories, oropharyngeal and esophageal. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia: Oropharyngeal dysphagia is caused by diseases or disorders affecting the mouth and throat. These may include: • Stroke. Stroke may affect the parts of the brain that control the voluntary phase of swallowing in the mouth. Between 51 and 73 percent of stroke patients develop dysphagia. • Brain tumors, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease. These disorders prevent impulses from the brain and cranial nerves reaching the muscles of the mouth and throat. • Syphilis. Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease that causes nerve cells in the spinal cord to degenerate during its third or final stage. The loss of these cells can affect swallowing as well as walking, hearing, and sight. • Abnormalities of the upper esophageal sphincter. Some people have a sphincter that does not relax normally during swallowing. In others, the sphincter closes too quickly. This overly rapid closure eventually results in the formation of a pouch in the upper esophageal wall. • Cancerous tumors of the throat and esophagus. These cause dysphagia by blocking the passage of food. • Myasthenia gravis, polio, and muscular dystrophy. Diseases affecting skeletal muscles elsewhere in the body also affect swallowing. • Esophageal rings and webs of tissue. These are noncancerous membranes along the walls of the esophagus that some people are born with. Symptoms Associated with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia Include: • Coughing or choking. • A nasal quality to the patient's voice. • Regurgitation. Regurgitation refers to food coming back up through the mouth or nose when swallowing is not proceeding normally. • Aspiration. Aspiration occurs when the bolus enters the respiratory system (the windpipe and lungs) rather than proceeding down the digestive tract. • Some seniors experience globus along with the dysphagia. • Chest pain. This symptom is often found in anxious or depressed patients with dysphagia. • Bad breath. This is a common symptom of Zenkel's diverticulum. Esophageal Dysphagia: Causes of esophageal dysphagia include: • Achalasia. Achalasia is a disorder in which the sphincter at the lower end of the esophagus does not relax normally and allow food to enter the stomach. • Scleroderma. This is a disease characterized by fibrous deposits of collagen in the skin and internal organs. It can cause a narrowing of the esophagus near the point at which it joins the stomach. • Spontaneous spasms of the muscles of the esophagus. • Narrowing of the lower portion of the esophagus by tumors. • Narrowing of the lower end of the esophagus caused by scarring from radiation treatments, certain medications (most commonly antibiotics, NSAIDs, and potassium chloride), or peptic ulcers. Symptoms of Esophageal Dysphagia Include: • A sensation of food sticking in the back of the throat or further down the chest. The patient's identification of the trouble spot, however, may not be the actual location of the blockage or narrowing. • Pain or a feeling of heartburn underneath the breastbone. • Regurgitation. • Changing dietary habits, typically eating fewer solid foods and taking in more liquids and soft foods. Neurological Causes Affecting Swallowing Neurologic disorders affecting swallowing can be categorized in many ways, including by the anatomic site of the lesion such as the central or peripheral nervous system, by the pathologic process such as ischemia and degeneration, by the underlying etiology, or by the clinical presentation such as dementia and movement disorders. Disorders of the central nervous system (CNS) can be nondegenerative or degenerative. Based on the clinical progression, degenerative disorders may be subclassified into progressive and relapsing disorders. Progressive degenerative disorders may be further subclassified based on their salient clinical characteristic into dementias and movement disorders. In contrast to the CNS, most of the peripheral nervous system disorders that impact swallowing is degenerative in nature. Stroke: A stroke occurs when the blood supply to your brain is interrupted or reduced. This deprives your brain of oxygen and nutrients, which can cause your brain cells to die. A stroke may be caused by a blocked artery (ischemic stroke) or the leaking or bursting of a blood vessel (hemorrhagic stroke). The signs of a stroke include a sudden severe headache, weakness, numbness, vision problems, confusion, trouble walking or talking, dizziness and slurred speech. Swallowing abnormalities in stroke are variable and may include oral lateral sulci retention, delayed oral transfer, delayed elicitation of a pharyngeal swallow, decreased hyolaryngeal elevation, and aspiration. Traumatic brain Injury: Traumatic brain injury can result in dysphagia depending on the brain region involved. Brain injury resulting from trauma is generally more diffuse than that following stroke, and cognitive impairments are often prominent depending on the site and severity of injury. Amyotrophic Lateral sclerosis: Motor neurone disease (MND) causes a progressive weakness of many of the muscles in the body. There are various types of MND. This leaflet is mainly about amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which is the most common type of MND. The cause is not known. It is thought that certain chemicals or structures that only occur in motor nerves are damaged in some way. The reason why the nerves become damaged is not clear. May experience some difficulties with swallowing as the muscles which co-ordinate swallowing become affected. Eating and swallowing become difficult when the tongue and the muscles around the mouth and throat become weak. Parkinson’s Disease: The main symptoms of Parkinson's disease are usually stiffness, shaking (tremor), and slowness of movement. A small part of the brain called the substantia nigra is mainly affected. This area of the brain sends messages down nerves in the spinal cord to help control the muscles of the body. Messages are passed between brain cells, nerves and muscles by chemicals called neurotransmitters. Dopamine is the main neurotransmitter that is made by the brain cells in the substantia nigra. Swallowing may become troublesome and saliva may pool in the mouth. Problems with controlling impulses. For example, compulsive eating arises. Progressive supranuclear palsy: Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a rare and progressive condition that can cause problems with balance, movement, vision, speech and swallowing. It's caused by increasing numbers of brain cells becoming damaged over time. PSP occurs when brain cells in certain parts of the brain are damaged because of a build-up of a protein called tau. Tau occurs naturally in the brain and is usually broken down before it reaches high levels. In people with PSP, it isn't broken down properly and forms harmful clumps in brain cells. The amount of abnormal tau in the brain can vary among people with PSP, as can the location of these clumps. This means the condition can have a wide range of symptoms. As PSP progresses to an advanced stage, people with the condition normally begin to experience increasing difficulties controlling the muscles of their mouth, throat and tongue. The loss of control of the throat muscles can lead to severe swallowing problems, which may mean a feeding tube is required at some point to prevent choking or chest infections caused by fluid or small food particles passing into the lungs. Myasthenic Gravis: Myasthenia gravis is a condition where muscles become easily tired and weak. It is due to a problem with how the nerves stimulate the muscles to tighten (contract). The muscles around the eyes are commonly affected first. This causes drooping of the eyelid and double vision. People with myasthenia gravis have a fault in the way nerve messages are passed from the nerves to the muscles. The muscles are not stimulated properly, so do not tighten (contract) well and become easily tired and weak. The fault is due to a problem with the immune system. Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease. This means that the immune system (which normally protects the body from infections) mistakenly attacks itself. Muscles around the face and throat are also often affected. Difficulty in swallowing and slurred speech may be the first signs of myasthenia gravis. Choking and accidentally inhaling bits of food, which can lead to repeated chest infections. Multiple sclerosis: Multiple sclerosis is a disorder of the brain and spinal cord. It can cause various symptoms. Tremors or spasms of some of your muscles may occur. This is usually due to damage to the nerves that supply these muscles. Some muscles may shorten (contract) tightly and can then become stiff and harder to use. Swallowing becomes difficult. Huntington’s disease: Huntington's disease is an inherited disease that causes the progressive breakdown (degeneration) of nerve cells in the brain. Huntington's disease has a broad impact on a person's functional abilities and usually results in movement, thinking (cognitive) and psychiatric disorders. The earliest symptoms are often subtle problems with mood or mental abilities. A general lack of coordination and an unsteady gait often follow. As the disease advances, uncoordinated, jerky body movements become more apparent. Physical abilities gradually worsen until coordinated movement becomes difficult and the person is unable to talk. Mental abilities generally decline into dementia. Difficulties with eating and swallowing (dysphagia) and maintaining a constant body weight are among the most troublesome complications of Huntington Disease (HD). There are many factors involved and many reasons why these problems occur. These include: Most people with HD have voracious appetites. They always seem to be hungry and tend to cram food into their mouths to try to satisfy their hunger, causing problems with choking and loss of food by spillage. Feeding and eating difficulties arise from the choreiform movements of the face and neck, incomplete lip closure and irregular movements of the diaphragm. The loss of fine muscle control and co-ordination can make eating a tiring and frustrating experience. Independent eating is also made difficult by the involuntary movements of the upper body and difficulties with fine motor control and co-ordination, making feeding oneself increasingly difficult. Swallowing problems are rarely a complaint at the time of diagnosis of Huntington Disease, however, as the disease progresses, the co-ordination of the swallowing mechanism becomes more and more impaired. Along with poor co-ordination, protection of the airway is also compromised due to sudden unpredictable gulps of air during the inhalation cycle of breathing. When inhalation occurs, the vocal cords are open and the airway is exposed, creating a high risk for aspiration of food particles into the open airway. sometimes there is a too rapid or immediate attempt to swallow which triggers coughing and choking. Preparatory Phase: Getting food from plate to utensil to mouth includes correct bite size and pace of eating. Chorea and impaired fine motor skills interfere with the mechanics of of food delivery, making it harder to control bite size and the pace of eating so that "gulping" occurs. A care partner who cues or assists in feeding is essential. Oral phase: Main problems include chorea of the tongue, and uncoordinated movement of food to the back of the throat. There is delay in starting the swallow, repeating of the swallow, or food left in the mouth after the swallow. Food consistency in each bite is important; a bowl of cereal is a set up for choking because the liquid may get to the back of the throat faster than the solid. Placing softer food in the cheek by the molars helps overcome the slowness of propelling food to the back of the throat. Starting the meal with something sour may help speed subsequent swallows. A "chin tuck" position of the neck is probably preferred for protecting against aspiration. Pharyngeal: Choking, coughing, aspiration: Small bites, thickened liquids, softer moist foods, progressing to smashed, then pureed consistencies. Part of this is due to "respiratory" chorea, which causes breathing during a swallow. Esophageal: Regurgitation of food or vomiting. There is also evidence of muscle dysfunction in the esophagus that may cause pain. It is important to stay upright for at least an hour after eating. Dementia: Dementia is characterized by a decline in one or more major cognitive domains (i.e., language, visuospatial functions) accompanied by impairment in memory. There are multiple causes of dementia. Patients with dementia not only have problems with swallowing but also with feeding in that they may have limb apraxia affecting their ability to use eating utensils and agnosia affecting their ability to recognize and accept food. Deficits in transfer of the bolus in the oral cavity are also prominent. Head and neck cancer: Speech and swallowing rehabilitation for people with head and neck cancer is a complex. Treatment for oral cancer usually involves surgery with, or without, radiotherapy, and this often impacts on speech and/or swallowing function. Surgery to the tongue can impact on the oral stage of swallowing, as well as on speech. The degree of impairment is largely dependent on the extent of lingual tissue resected and it has been stated by Lazarus that, “if less than 50% of the tongue is resected and reconstruction is by primary closure, patients can regain functional swallowing”.5 Patients requiring total glossectomy are, unfortunately, usually limited to a diet of thin and/or thick fluids, and use postural/ compensatory techniques to swallow orally. If a mandibulectomy occurs, limitations to lip and jaw movements will reduce speech intelligibility and the oral stage of swallowing will be slow. Resection of either the hard or soft palate can result in hypernasal speech and oral bolus residue or nasal regurgitation of food/fluids may be observed, if the surgical repair is ineffective. Sites of oropharyngeal cancer include the soft palate, retromolar trigone, tonsils, base of tongue and superior and lateral pharynx. If the base of tongue or pharyngeal wall is affected, then speech may not necessarily be grossly impaired, but swallowing almost certainly will be. The movement of the tongue base is crucial to the efficiency of the swallow, as this area contributes, via its pressure generation against the pharyngeal wall, to the propulsion of the bolus through the pharynx. Laryngectomy: Laryngectomy is the removal of the larynx and separation of the airway from the mouth, nose and esophagus. In a total laryngectomy, the entire larynx is removed (including the vocal folds, hyoid bone, epiglottis, thyroid and cricoid cartilage and a few tracheal cartilage rings). In a partial laryngectomy, only a portion of the larynx is removed. Following the procedure, the person breathes through an opening in the neck known as a stoma. With an early cancer of the glottis (larynx) on one, or both vocal folds, a patient’s initial complaint at presentation is often that of a hoarse/husky voice. The laryngectomy surgery results in anatomical and physiological changes in the larynx and surrounding structures. Consequently, swallowing function can undergo changes as well, compromising the patient's oral feeding ability and nutrition. Patients may experience distress, frustration, and reluctance to eat out due to swallowing difficulties. A total laryngectomy causes the separation of the upper air respiratory tract (pharynx, nose, mouth) and lower air respiratory tract (lungs, lower trachea).[24] Breathing is no longer done through the nose (nasal airflow), which causes a loss/decrease of the sense of smell, leading to a decrease in the sense of taste.